Abstract

Dolichols are isoprenoid lipids of varying length that act as sugar carriers in glycosylation reactions in the endoplasmic reticulum. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, there are two cis-prenyltransferases that synthesize polyprenol—an essential precursor to dolichol. These enzymes are heterodimers composed of Nus1 and either Rer2 or Srt1. Rer2-Nus1 and Srt1-Nus1 can both generate dolichol in vegetative cells, but srt1∆ cells grow normally while rer2∆ grows very slowly, indicating that Rer2-Nus1 is the primary enzyme used in mitotically dividing cells. In contrast, SRT1 performs an important function in sporulating cells, where the haploid genomes created by meiosis are packaged into spores. The spore wall is a multilaminar structure and SRT1 is required for the generation of the outer chitosan and dityrosine layers of the spore wall. Srt1 specifically localizes to lipid droplets associated with spore walls, and, during sporulation there is an SRT1-dependent increase in long-chain polyprenols and dolichols in these lipid droplets. Synthesis of chitin by Chs3, the chitin synthase responsible for chitosan layer formation, is dependent on the cis-prenyltransferase activity of Srt1, indicating that polyprenols are necessary to coordinate assembly of the spore wall layers. This work shows that a developmentally regulated cis-prenyltransferase can produce polyprenols that function in cellular processes besides protein glycosylation.

Keywords: lipid droplet, dolichol, cis-prenyltransferase, Chs3, chitosan, Srt1, sporulation, yeast

DOLICHOLS and polyprenols are polyisoprenoid lipids found in all cellular organisms. Their best understood function is as sugar carriers in glycosylation reactions (Abu-Qarn et al. 2008). In eukaryotic cells, dolichol phosphate acts as a sugar carrier for N- and O-linked glycosylation as well as glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchor synthesis in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Burda and Aebi 1999; Loibl and Strahl 2013; Grabińska et al. 2016). Polyprenols and dolichols are also found in other cellular membranes besides the ER, but their function in other organelles is unclear.

Polyisoprenoids are formed by the action of cis-prenyltransferase enzymes. These enzymes iteratively add 5-carbon isopentenyl groups onto a farnesyl diphosphate “seed” to produce polyprenols—polymers of 14–24 repeating isopentenyl units (Sato et al. 2001). Additional enzymes in the ER saturate the final isopentenyl unit in the polyprenol, creating dolichol (Swiezewska and Danikiewicz 2005). In yeast, the paralogous proteins Rer2 and Srt1 independently associate with a common subunit, Nus1, to generate two different cis-prenyltransferase complexes (Sato et al. 1999, 2001; Schenk et al. 2001; Park et al. 2014).

The Srt1-Nus1 and Rer2-Nus1 complexes differ in several ways. First, while Rer2 is localized to both the ER and lipid droplets in vegetative cells (Currie et al. 2014), Srt1 is primarily localized to lipid droplets (Sato et al. 2001). Second, Rer2 produces shorter polyprenols, averaging 15 isoprene repeat units, while Srt1 produces longer polyprenols, averaging 21 isoprene repeats (Sato et al. 2001). Third, in vegetative cells, SRT1 is expressed primarily in stationary phase, while RER2 is constitutively expressed (Sato et al. 2001). Finally, rer2∆ cells show severe growth defects and glycosylation defects (Sato et al. 1999), while srt1∆ mutants do not. Nonetheless, there is some overlap in function as srt1∆ and rer2∆ are synthetically lethal and cells deleted for NUS1 are inviable (Sato et al. 1999; Yu et al. 2006). Also, SRT1 overexpression can correct the rer2∆ glycosylation defect (Sato et al. 1999; Grabińska et al. 2005, 2010; Kwon et al. 2016).

Rer2-Nus1 is the primary cis-prenyltransferase required for dolichol synthesis for protein glycosylation in the ER in vegetative cells, but the role of SRT1 in cells has been unclear. Although no vegetative phenotypes of srt1∆ have been reported, SRT1 was identified in three different genome-wide screens for mutants that decreased sporulation, raising the possibility that the Srt1 cis-prenyltransferase is required for a novel function in spore formation (Deutschbauer et al. 2002; Enyenihi and Saunders 2003; Marston et al. 2004).

Under conditions of nitrogen starvation and the absence of a fermentable carbon source, diploid cells of S. cerevisiae undergo meiosis and sporulation, in which the four haploid nuclei produced by the meiosis are packaged into haploid spores within the mother cell cytoplasm (Neiman 2011). The outside of each spore is composed of a complex wall that provides increased resistance to various external stresses (Coluccio et al. 2004, 2008).

Spore formation begins early in Meiosis II (MII), when secretory vesicles coalesce at the cytoplasmic face of each of the four spindle pole bodies, resulting in the formation of four prospore membranes (Neiman 1998). Each prospore membrane grows to engulf a haploid genome and a portion of the cytoplasmic content (Byers 1981). Closure of the prospore membrane separates the spore and mother cell cytoplasm by two lipid bilayers with a lumenal space between them. The spore wall is then constructed within this lumenal space (Lynn and Magee 1970). The lipid bilayer closest to the nucleus goes on to form the spore plasma membrane, while the outer bilayer is lysed during spore wall formation (Coluccio et al. 2004).

There are four distinct layers to the spore wall. Going from closest to the spore plasma membrane outward, the layers are composed primarily of (1) mannan (i.e., mannosylated proteins); (2) β-1,3-glucan; (3) chitosan; and (4) dityrosine (Neiman 2011). The inner two layers are similar in composition to the layers of the vegetative cell wall, though they are arranged in reverse order with respect to the plasma membrane (Kreger-Van Rij 1978; Smits et al. 2001). The chitosan and dityrosine layers are unique to spores and are essential for increased stress resistance (Briza et al. 1988, 1990a,b; Pammer et al. 1992).

The spore wall layers are assembled sequentially beginning with the mannan layer (Tachikawa et al. 2001). After the deposition of the mannan and glucan layers, the outer membrane bilayer derived from the prospore membrane lyses, placing the glucan layer in contact with the ascal (mother cell) cytoplasm. The outer chitosan layer is then constructed and the wall is finished by the deposition of dityrosine into the wall (Coluccio et al. 2004). Proper construction of the dityrosine layer is dependent on prior assembly of the chitosan layer (Coluccio et al. 2004).

Chitosan is a polysaccharide composed of β-1,4-glucosamine (Briza et al. 1988). The chitosan layer of the spore wall is formed through the sequential action of the chitin synthase, Chs3, and the chitin deacetylases, Cda1 and Cda2 (Pammer et al. 1992; Christodoulidou et al. 1996, 1999). Chs3 is a polytopic transmembrane protein that produces chitin (β-1,4-N-acetylglucosamine) from uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) in the cytoplasm, and extrudes the polymer through the plasma membrane (Cabib et al. 1983; Pammer et al. 1992). Cda1 and Cda2 are enzymes localized to the spore wall that deacetylate chitin chains, converting them to chitosan (Christodoulidou et al. 1996, 1999; Mishra et al. 1997). In the absence of both CDA1 and CDA2, chitin accumulates in the spore wall rather than chitosan (Christodoulidou et al. 1999; Lin et al. 2013). The chitin is not assembled into a discrete layer, however, and, as a result, both the chitosan and dityrosine layers are absent in a cda1∆ cda2∆ mutant.

Chitin deposition is timed with the cell cycle, and the activity of Chs3 is tightly controlled during vegetative growth to allow deposition of chitin at the bud neck (Shaw et al. 1991; Pammer et al. 1992; Choi et al. 1994; Chuang and Schekman 1996; Kozubowski et al. 2003). Chs4 (also called Skt5) is a key regulator of Chs3 that controls Chs3 activity in two ways: (1) Chs4 binds Chs3 and allosterically activates the enzyme, and (2) it controls delivery of Chs3 to the bud neck through interactions with transport factors (Ono et al. 2000; Kozubowski et al. 2003).

In sporulating cells, chitin is synthesized at the spore wall, thereby requiring sporulation-specific regulation of Chs3 localization, which is mediated by the sporulation-specific Sps1 kinase (Iwamoto et al. 2005). Yeast cells also contain a sporulation-specific paralog of Chs4 called Shc1 (Sanz et al. 2002). Shc1 is capable of the allosteric activation function of Chs4 but not the localization function, as ectopic expression of SHC1 in vegetative cells activates Chs3 but does not properly localize it to the bud neck. Furthermore, shc1∆ diploids display modest spore wall defects, suggesting a role for SHC1 in Chs3 activation during sporulation.

Another factor involved in formation of the outer spore wall is lipid droplets (Hsu et al. 2017). Lipid droplets are organelles composed of a monolayer of phospholipids surrounding a core of neutral lipids (Wang 2015). They act as sites of both lipid storage and metabolism (Kohlwein et al. 2013). It is possible for cells to sporulate while lacking lipid droplets that contain either triglycerides or sterol esters, but the absence of any lipid droplets leads to defects in both prospore membrane growth and spore wall assembly (Hsu et al. 2017). This result suggests that some lipid droplet factor besides the neutral lipids is essential for proper sporulation.

During sporulation, a subset of lipid droplets associates with the forming prospore membrane (Lin et al. 2013). After closure, these droplets remain associated with the outer membrane derived from the prospore membrane. After lysis of the outer membrane the lipid droplets associate with the outer spore wall. These external lipid droplets gradually dwindle both in size and number over the course of spore wall development (Lin et al. 2013). Spore wall associated droplets can be distinguished from lipid droplets in the spore cytoplasm by their localization, as well as by specific protein constituents (Ren et al. 2014). Several lipid droplet proteins are specifically associated with spore-wall-associated droplets during sporulation (Lam et al. 2014; Ren et al. 2014). For instance, three paralogous proteins, Lds1, Lds2, and Rrt8 all localize solely to the spore wall lipid droplets and the triple mutant displays defects in formation of the dityrosine layer, indicating a role in spore wall development (Lin et al. 2013). Srt1 and Nus1 both localize to these lipid droplets, suggesting that cis-prenyltransferase activity may be present in these spore-wall-associated lipid droplets (Sato et al. 2001; Currie et al. 2014; Lam et al. 2014).

This work shows that SRT1 functions during sporulation to generate long chain polyisoprenoids in spore-wall-associated lipid droplets. These polyisoprenoids activate the Chs3 chitin synthase to generate the chitin, which is then modified to make the chitosan layer of the spore wall. The finding that polyprenols are required for a developmentally regulated process in sporulating yeast suggests that this interesting type of molecule may have additional roles in other cellular processes beyond glycosylation in the ER.

Materials and Methods

Yeast strains and media

Unless otherwise mentioned, standard yeast media and genetic techniques were used (Rose et al. 1990). All the strains used, except AN512, are derived from the SK1 background, and their genotypes are listed in Table 1. Primer sequences are listed in Table 2. AN512 was created by mating the SK1 haploid AN117-4B to an srt1Δ mutant in the BY4741 background from the Saccharomyces Deletion Collection (Giaever et al. 2002), dissecting the resulting diploid, and mating srt1∆ segregants with each other. RHY1 and RHY2 (srt1∆) were made by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-mediated homologous recombination in AN117-16D and S2683 respectively, using the primers CK33 and CK34 with pFA6a-kanMX6 (Bahler et al. 1998) as the template. RHY1 and RHY2 were mated to form RHY19 (srt1∆/srt1∆). RHY27 and RHY28 (chs4∆) were made by PCR-mediated homologous recombination in AN117-4B and AN117-16D respectively, using the primers RHO28 and RHO29 with pFA6a-kanMX6 as the template. RHY27 and RHY28 were mated to form RHY29 (chs4∆/chs4∆). AN1092 and AN1093 (shc1∆) were made by PCR-mediated homologous recombination in AN117-4B and AN117-16D respectively, using the primers ANO274 and ANO275 with pFA6a-His3MX6 (Longtine et al. 1998) as the template. AN1092 and AN1093 (shc1∆) were mated to form AN270 (shc1∆/shc1∆). RHY23 and RHY24 (chs4∆ shc1∆) were made by PCR-mediated homologous recombination to delete CHS4 in AN1092 and AN1093 (shc1∆), respectively, using the primers RHO28 and RHO29 with pFA6a-kanMX6 as the template. RHY23 and RHY24 (chs4∆ shc1∆) were mated to form RHY26 (chs4∆/chs4∆ shc1∆/shc1∆). RHY37 and RHY38 (chs4∆ shc1∆) were segregants from a cross between AN1092 (shc1∆) and RHY28(chs4∆), and were mated to form RHY39 (chs4∆/chs4∆ shc1∆/shc1∆). RHY19-P1 and RHY19-P2 were created by transforming RHY1 and RHY2 (srt1Δ) with the integrating vectors pRS306-SRT1 or pRS306-srt1-D75A, and mating the transformants to produce homozygous diploids.

Table 1. Yeast strains.

| Name | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| AN117-4B | MATα ura3 leu2 his3∆SK trp1Δ::hisG arg4-NspI lys2 rme1Δ::LEU2 ho∆::LYS2 | Neiman et al. (2000) |

| AN117-16D | MATa ura3 leu2 his3∆SK trp1∆::hisG lys2 hoΔ::LYS2 | Neiman et al. (2000) |

| S2683 | MATα ura3 lys2 leu2-k arg4-NspI ho∆LYS2 | Woltering et al. (2000) |

| AN120 | MATα ura3 leu2 his3∆SK trp1Δ::hisG arg4-NspI lys2 | Neiman et al. (2000) |

| MATa ura3 leu2 his3∆SK trp1∆::hisG ARG4 lys2 | ||

| ho∆::LYS2 rme1Δ::LEU2 | ||

| hoΔ::LYS2 RME1 | ||

| AN262 | Same as AN120 except chs3∆::HIS3MX6 | Coluccio et al. (2004) |

| chs3∆::HIS3MX6 | ||

| AN264 | Same as AN120 except dit1∆::HIS3MX6 | Coluccio et al. (2004) |

| dit1∆::HIS3MX6 | ||

| AN512 | MATa ura3 his3 leu2 trp1 LYS2 arg4 rme1∆::LEU2 | This study |

| MATα ura3 his3 leu2 trp1 lys2 ARG4 RME1 | ||

| srt1∆:::kanMX6 | ||

| srt1∆:::kanMX6 | ||

| AN1092 | MATα ura3 his3∆SK trp1::hisG arg4-NspI lys2 leu2 rme1∆::LEU2 shc1∆::HIS3MX6 ho∆::LYS2 | This study |

| AN1093 | MATa ura3 his3∆SK trp1::hisG lys2 leu2 shc1∆::HIS3MX6 ho∆::LYS2 | This study |

| AN270 | Same as AN120 except shc1∆::HIS3MX6 | This study |

| shc1∆::HIS3MX6 | ||

| CL50 | Same as AN120 except cda1,2∆:: hphMX3 | Lin et al. (2013) |

| cda1,2∆:: hphMX3 | ||

| RHY1 | MATa ura3 lys2 leu2 trp1-hisG his3∆SK srt1∆::kanMX6 ho::LYS2 | This study |

| RHY2 | MATα ura3 lys2 leu2-k arg4-NspI srt1∆::kanMX6 ho∆LYS2 | This study |

| RHY19 | MATa ura3 lys2 leu2 trp1-hisG ARG4 his3∆SK | This study |

| MATα ura3 lys2 leu2-k TRP1 arg4-NspI HIS3 | ||

| srt1∆::kanMX6 ho∆::LYS2 | ||

| srt1∆::kanMX6 ho∆::LYS2 | ||

| RHY19-P1 | Same as RHY19 with pRS306-SRT1 (URA3 SRT1) | This study |

| pRS306-SRT1 | ||

| RHY19-P2 | Same as RHY19 with pRS306-srt1-D75A (URA3 srt1-D75A) | This study |

| pRS306-srt1-D75A | ||

| RHY27 | MATα ura3 leu2 his3∆SK trp1Δ::hisG arg4-NspI lys2 rme1Δ::LEU2 chs4Δ::kanMX6 ho∆::LYS2 | This study |

| RHY28 | MATa ura3 leu2 his3∆SK trp1∆::hisG lys2 chs4Δ::kanMX6 hoΔ::LYS2 | This study |

| RHY29 | Same as AN120 except chs4∆::kanMX6 | This study |

| chs4∆::kanMX6 | ||

| RHY23 | Same as AN117-4B except chs4∆::kanMX6 shc1∆::HIS3MX6 | This study |

| RHY24 | Same as AN117-16D except chs4∆::kanMX6 shc1∆::HIS3MX6 | This study |

| RHY26 | Same as AN120 except chs4∆::kanMX6shc1∆::HIS3MX6 | This study |

| chs4∆::kanMX6 shc1∆::HIS3MX6 | ||

| RHY37 | MATα ura3 leu2 his3∆SK trp1Δ::hisG lys2 ho∆::LYS2 chs4∆::kanMX6 shc1∆::HIS3MX6 | This study |

| RHY38 | MATa ura3 leu2 rme1Δ::LEU2 his3∆SK trp1∆::hisG lys2 arg4-NspI hoΔ::LYS2 chs4∆::kanMX6 shc1∆::HIS3MX6 | This study |

| RHY39 | Same As RHY26 | This study |

| RHY16 | Same as AN120, except CHS3::3xsfGFP::kanMX6 | This study |

| CHS3::3xsfGFP::kanMX6 | ||

| RHY42 | Same as RHY16 | This study |

| RHY44 | Same as AN120 except CHS3-3xsfGFP::kanMX6 srt1∆::kanMX6 | This study |

| CHS3-3xsfGFP::kanMX6 srt1∆::kanMX6 |

Table 2. Primers used in this study.

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| CK33 | GTTCGGAGAAGGTTTAACAGTTCTGATTCTTTGCATTCTTTGAGTCGAAGCTTCAACTCGAGAGCGAAATCGGATCCCCGGGTTAATTAA |

| CK34 | TAATTAAAAATGATGTAATATGGTAATAGGTATGGAAGAATCAGGGAGTTTTCAGAATGTTCTTTGCCCTGAATTCGAGCTCGTTTAAAC |

| RHO28 | GTTAATAAGCCTTCCATTGTATACTACCAGGTTCTCGTCTTTTTTGGTGATAAAGTTAAAATAAAAGGATCGGATCCCCGGGTTAATTAA |

| RHO29 | TTGTATCACTATATGCATTGAGTGTAAACTGTTGCACCTATAAAGAATGAAAACAATCTAGTATGTGTACGAATTCGAGCTCGTTTAAA |

| ANO274 | AGTACGGTTGACATTACGAGTATCCCTTTGTTAAAATCAGGCAGTACCCATACGGATCCCCGGGTTAATTAA |

| ANO275 | AGTTTAGTCTCCACAGTTTGTGAAAAAAAAAACAACAAAATAAAAGGAAAACGAAGTTTGTATTTATCTAGAATTCGAGCTCGTTTAAAC |

| YSO1 | AAAGGGAAGATATTCTCAATCGGAAGGAGGAAAGTGACTCCTTCGTTGCACGGATCCCCGGGTTAATTAA |

| YSO2 | ATAAGTTACACACAACCATATATCAACTTGTAAGTATCACAGTAAAAATAGAATTCGAGCTCGTTTAAAC |

| CK25 | GTTCTTGCGGCCGCACTTCCGCTAACGCTGATGG |

| RHO07 | GCCTCCCTCGAGAGGGGATTTCGATGACCTAG |

| RHO08 | CTCCTTTATCATGGCTGGTAACCGGAGATA |

| RHO09 | TATCTCCGGTTACCAGCCATGATAAAGGAG |

| RHO43 | GCCTTCTTGACTTGGCATATCTCC |

| RHO44 | GGGAACAAAAGCTGGGTACCACTTCCGCTAACGCTGATGG |

RHY16 (CHS3-3xsfGFP/CHS3-3xsfGFP) was created by tagging CHS3 at the C-terminus via PCR-mediated homologous recombination in AN117-4B and AN117-16D using a fragment containing three copies of superfolder green fluorescent protein (3xsfGFP) (Jin et al. 2017), amplified with the primers YSO1 and YSO2 with pFA6a-3xsfGFP -kanMX6 (a gift from G. Zhao) as the template. RHY42 (CHS3-3xsfGFP/CHS3-3xsfGFP) was created by dissecting RHY16 and crossing segregants with each other. RHY16 was dissected and a segregant crossed with RHY1 (srt1∆) to produce a double heterozygote (CHS3-3xsfGFP/CHS3 srt1∆/SRT1), which was then dissected and segregants crossed with each other to produce RHY44 (CHS3-3xsfGFP/CHS3-3xsfGFP srt1∆/srt1∆). In addition, a CHS3-3xsfGFP segregant from RHY16 was crossed with RHY37 (chs4∆ shc1∆) to produce a double heterozygote (CHS3-3xsfGFP/CHS3 chs4∆/CHS4 shc1∆/SHC1), which was dissected and segregants were crossed with each other to produce RHY57 (chs3-3xsfGFP/chs3-3xsfGFP chs4∆/chs4∆ shc1∆/shc1∆).

Plasmids

pRS306-SRT1 was created by amplifying a 1.7-kb genomic fragment from SK1 strain AN120 (−382 from the start codon to +276 bp past the stop codon) containing SRT1 using the primers CK25 and RHO07. The fragment was engineered to have NotI and XhoI restriction sites on either end. The NotI/XhoI digested fragment was then cloned into NotI/XhoI digested pRS306 (Sikorski and Hieter 1989). This plasmid was used as the template for site-directed mutagenesis to change codon 75 from GAT to GCT (aspartic acid to alanine: D75A) using the primers RHO08 and RHO09 (Quikchange kit, Stratagene). The resulting 6.1-kb product was digested with DpnI to remove the wild-type plasmid and transformed into Escherichia coli (BSJ72). Sequencing of the entire srt1-D75A allele from the resulting plasmid, pRS306-srt1-D75A, confirmed the presence of the mutation and the absence of any additional changes. Sequencing was performed by the Stony Brook University DNA Sequencing facility. Both pRS306-SRT1 and pRS306-srt1-D75A were linearized with StuI to target integration to ura3 in the yeast genome.

To construct a green fluorescent protein (GFP) tagged allele of SRT1, a ∼7.0-kb KpnI/BstEII fragment containing SRT1232-1032-GFP and the pRS316 backbone was isolated from pLN-SRT1-GFP (gift from L. Needleman). A second fragment containing the promoter region (−382) and the first 256 bases of SRT1 was amplified from pRS306-SRT1 using the primers RHO43 and RHO44, with one end containing overlapping homology adjacent to the KpnI site on pRS316, and the other end overlapping the BstEII site in SRT1. These two fragments were then joined together using the Gibson Assembly kit from Invitrogen (GeneArt Seamless Cloning and Assembly Kit, A13288) to make pRS316-SRT1-GFP (Gibson et al. 2009). The srt1-D75A-GFP allele was similarly constructed in pRS316 except that the fragment containing the promoter and the first 256 bases of SRT1 was amplified from pRS306-srt1-D75A. Both the SRT1 and srt1-D75A open reading frames (ORFs) in these plasmids were sequenced in their entirety to ensure no unexpected mutations were present. pRS426-Spo2051-91-RFP and pRS424-Spo2051-91-RFP have been previously characterized (Suda et al. 2007).

Sporulation

Single colonies of each strain were inoculated into 3 ml of YPD medium and grown on a roller overnight at 30°. These cultures were used to inoculate 25 ml of Yeast Peptone Acetate (YPA) medium in 250 ml flasks to a final OD660 (optical density 660 nm) of 0.1–0.2 (usually a 1:25 or 2:25 dilution) and incubated overnight at 30° on a shaker at 250 rpm. Cell cultures with OD660 values between 0.7 and 1.3 were harvested in a Fischer Scientific Centrific centrifuge model 255 using a four-bucket model 215 rotor on setting 4 for 5 min. The cell pellets were washed once with water, pelleted in the same manner, and resuspended in SPO medium (2% KOAc) in 250 ml flasks to a final concentration of 2 × 107 cells/ml (a typical volume of 15–30 ml) and incubated with shaking at 30°. Spo2051-91-RFP was used to monitor progression through meiosis (Suda et al. 2007). For immunoblots and Chs3 activity assays, cells were harvested as soon as at least 60% of cells were postmeiotic as determined by prospore membrane morphology.

Fluorescence imaging

Imaging was performed using a Zeiss Observer.Z1 microscope with an attached Orca II ERG camera (Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ). ZEN 2012 (Blue edition) software was used to acquire images. For imaging of lipid droplets, monodansylpentane (Abgent SM1000a) was used (Yang et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2017).

Calcofluor White and Eosin Y staining

Staining was performed as described in Lin et al. (2013) with the following modifications. Prior to staining, 1 ml of cells were centrifuged at 5900 × g for 15 sec in a 2-ml microfuge tube, washed once with water, and resuspended in 250 μl water containing 1.0 mg/ml zymolyase (20,000 units/g; Amsbio). Cells were incubated at room temperature until spores were released from the asci, as determined by light microscopy, usually 5 min. Cells were centrifuged at 5900 × g for 15 sec, washed once in 1 ml McIlvaine’s buffer [0.2 M Na2HPO4/0.1 M citric acid (pH 6.0)], and resuspended in 500 μl McIlvaine’s buffer. Cells were stained by the addition of 30 μl Eosin Y disodium salt (Sigma) (5 mg/ml) for 10 min at room temperature in the dark. After staining, cells were washed three times in 500 μl of McIlvaine’s buffer, until the supernatant was clear of residual Eosin Y, and then the cells were resuspended in 50–200 μl of McIlvaine’s Buffer based on the size of the pellet; 7 μl of the final suspension was placed on a glass slide, to which 0.5 μl of 1 mg/ml Calcofluor White (CFW) was added prior to application of a cover slip. The spores were then visualized using filter cubes for blue (excitation 360 nm, emission 460 nm) or red (excitation 540 nm, emission 605 nm) fluorescence. All images were collected at the same exposure time; 560 msec for Eosin Y, 180 msec for CFW.

Electron microscopy

Cells viewed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) were processed as described previously with minor modifications (Suda et al. 2007). Briefly, cells were collected in centrifuge tubes and fixed with 3% EM grade glutaraldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate (SC) buffer (pH 7.4) at room temperature. After fixation, samples were washed in SC buffer and resuspended in an aqueous 4% potassium permanganate solution, washed, stained with saturated uranyl acetate, dehydrated through a graded ethanol series (20–100%), and embedded in Epon resin (Electron Microscopy Sciences).

Alternately, after fixation, cells were rinsed in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, and resuspended in ultralow gelling temperature agarose (Promega) in 1.5 ml microfuge tubes. Agarose embedded samples were removed, and cut into smaller cubes with a scalpel. Samples were then suspended in aqueous 1% potassium permanganate, rinsed in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, treated with 0.5% sodium meta-periodate (Electron Microscopy Sciences), rinsed again, and dehydrated through a graded ethanol series. After dehydration, samples were embedded in Spurr’s resin (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and polymerized in a 60° oven.

Ultrathin sections of 80 nm were cut with a Reichert-Jung UltracutE ultramicrotome and placed on formvar coated slot copper grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences). Sections were viewed with a FEI Tecnai12 BioTwinG2 electron microscope located in the Stony Brook Center for Microscopy. Digital images were acquired with an AMT XR-60 CCD Digital Camera System.

Western blots

Lysis and protein preparation were performed as described in Knop et al. (1999) prior to loading on a 12% sodium dodecylsulfate-polyacrylamide gel with 1 mm spacers, prepared using a kit from Bio-Rad (#1610175). Samples were run for 20–30 min at 300 V. Blocking buffer was 6.5% (w/v) milk in TTBS (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20). Primary anti-GFP antibodies (JL-8, Clontec) and anti-Por1 antibodies (Molecular Probes) were used at 1:1000 dilution in blocking buffer and applied for 1 hr with shaking at room temperature. Secondary sheep anti-mouse IgG antibodies coupled to horseradish peroxidase were diluted 1:2500 (GE Healthcare) and applied for 1 hr with shaking at room temperature. Enhanced Chemiluminescence reagent (Amersham) was used to develop the blots, and quantification was performed using ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare).

Chs3 activity assay

Chs3 activity assays were performed as in Lucero et al. (2002) with the following modifications. The wells of microtiter plates (Falcon #353219) were coated in wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) by the addition of 100 μl 50 μg/ml WGA in 2.5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and incubation at room temperature for >16 hr. WGA solution was removed by repeated washes involving immersion in distilled water followed by vigorous shaking to remove the water. Wells were blocked by the addition of 300 μl of blocking buffer [20 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5] followed by incubation at room temperature for 3 hr. The plates were stored at −20° if not used immediately. Prior to use, plates were thawed at room temperature and the blocking buffer removed by shaking.

Sporulating cells were lysed by bead beating using a MP Biomedical FastPrep-24. Two pulses of 6 m/sec for 40 sec were used with a 3-min pause on ice between pulses. The beads were made of zirconia/silica and were 0.5 mm in diameter (BioSpec Products). Lysis buffer was 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, containing 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), as well as protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Sigma). The total protein concentration of the lysates was determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay kit calibrated with BSA standards.

Fifty microliter of a 2× reaction mixture consisting of 3.2 mM CoCl2, 10 mM NiCl2, 80 mM GlcNAc, and 4 mM UDP-GlcNAc in 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, was added to each well. For each well run with reaction buffer, another well was run with a 2× control mixture, which was identical except for lacking UDP-GlcNAc. Lysate and water were added to bring the total volume to 100 μl, and the final protein concentration to 0.33 μg/μl. Reactions were incubated for 90 min at 30°, and stopped by addition of 20 μl of 50 mM EDTA, which was mixed in by gentle shaking for 30 sec. The wells were then washed by repeated immersion of the plate in distilled water; 200 μl of 0.5 μg/ml wheat germ agglutinin bound to horseradish peroxidase (Sigma) in blocking buffer was then added to each well, and the plate was gently shaken and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. The plate was then washed by immersion in distilled water, and shaken to remove the water; 100 μl of 1-Step Ultra TMB-ELISA (3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine; Pierce) was added to each well, and the plate immediately placed in a plate reader (Bio Tek Synergy 2, operated by Gen5 2.0), and a 0 min timepoint reading taken at OD600. Further readings were taken at 2 min intervals and a 20 min endpoint. Results were analyzed as the average difference in activity between reaction and control samples. Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA and Tukey honest significant difference post hoc test.

Isolation of lipid droplets

Lipid droplet fractions were prepared as described in Athenstaedt (2010) with minor modifications. Briefly, vegetative cells or sporulating cells harvested by centrifugation were incubated for 10 min at 30° in 0.1 M Tris/SO4 buffer, pH 9.4, 10 mM dithiothreitol. Then, cells were treated with zymolyase in 1.2 M sorbitol, 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, for 2 hr at 30°. Spheroplasts were pelleted, washed, and resuspended in 10 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.4, 12% (w/w) Ficoll 400, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF homogenization buffer, to a final concentration of 0.5 g per cell wet weight per milliliter, and homogenized with a Dounce homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 5000 × g for 5 min at 4°; the resulting supernatant was transferred into a centrifuge tube, overlaid with an equal volume of homogenization buffer, and centrifuged for 2 hr at 100,000 × g in an SW40 rotor (Beckman Coulter). After centrifugation, the floating layer was collected from the top of the gradient and resuspended in homogenization buffer. The suspension was transferred into a fresh tube, and overlaid with 10 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.4, 8% (w/w) Ficoll 400, 0.2 mM EDTA, and centrifuged for 1 hr at 100,000 × g. The floating layer was removed from the top of the gradient and suspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 8% (w/w) Ficoll 400, 0.6 M sorbitol, 0.2 mM EDTA, and transferred to a fresh tube. The suspension was overlaid with 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.25 M sorbitol buffer. After a final centrifugation for 1 hr at 100,000 × g, a white layer of highly purified lipid droplets was collected from top of the gradient and saved for biochemical analysis.

The microsomal pellet from the initial 100,000 × g centrifugation was homogenized in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.25 M sorbitol buffer, and the homogenate was then centrifuged at 100,000 × g. The final pellet was saved for enzymatic analysis of cis-prenyltransferase activity in the microsomal fraction. The protein concentration of the lipid droplet fraction was determined after removing the lipids by extraction with three volumes of diethyl ether.

Cis-Prenyltransferase measurements

Cis-Prenyltransferase activity was measured as previously described (Szkopińska et al. 1997) with minor modifications. In the assay, addition of radio-labeled isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) groups to a farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) primer creates products that can be measured by the incorporation of radioactive label into a hydrophobic fraction. The reaction volume was 50 μl and contained 50 μM FPP), 100 μM [1-14C]-IPP (55 mCi/mmol) (American Radiolabeled Chemicals), 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM potassium fluoride, 10 μM zaragozic acid A, a membrane fraction containing 50 μg protein from the microsomal fraction, or 2 μg of protein from the purified lipid droplet fraction, and 50 μg of BSA. After 90 min incubation at 30°, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 1 ml of chloroform:methanol (3:2). The protein pellet was removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant was extracted three times with 1/5 volume of 10 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, in 0.9% NaCl solution. To analyze the products of the reaction, lipids before and after chemical dephosphorylation were loaded onto High Performance Thin Layer Chromatography Silica gel 60 Reverse Phase 18 (HPTLC Silica gel 60 RP-18) plates with a concentrating zone (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), and run in acetone containing 50 mM H3P04. Plates were exposed to a film and radiolabeled products were detected by autoradiography. To assess chain length of the polyprenols, internal standards of dolichol 19, and undecaprenol (American Radiolabeled Chemicals) were mixed with the sample after dephosphorylation and the unlabeled standards were visualized by exposure to iodine vapor. To chemically dephosphorylate polyprenol pyrophosphate, the chloroform fraction was evaporated under nitrogen and lipids were incubated at 80° in 1 N HCl for 1 hr. Polyprenols were extracted three times with two volumes of hexane. The organic fraction was washed with 1/3 volume of water. To measure the incorporation of radioactive IPP into the isoprenoid fraction, a portion of the chloroform fraction was subjected to liquid scintillation counting using a Tri-Carb 2100TR Liquid Scintillation Analyzer (Packard) scintillation counter to detect the amount of 14C in each sample.

Extraction of polyprenols and dolichols

To isolate polyprenols for analysis, either 300 mg of yeast cells or isolated lipid droplet fractions containing 19–50 μg of protein were suspended in 1 ml of 40% methanol. The suspension was subjected to saponification by incubation for 1 hr at 95° in the presence of 3 M KOH to hydrolyze fatty acid esters of dolichols and polyprenols. Lipids were further extracted from the samples by the modified Folch method (Szkopińska et al. 1997).

Analysis of dolichols and polyprenols by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS)

Dolichols and polyprenols were analyzed by LC-MS (Guan and Eichler 2011). LC was performed using a Zorbax SB-C8 reversed-phase column (5 μm, 2.1 × 50 mm) (Agilent) at a flow rate of 200 μl/min with a linear gradient as follows: 100% of mobile phase A (methanol/acetonitrile/aqueous 1 mM ammonium acetate (60/20/20, v/v/v) was held isocratically for 2 min, and then linearly increased to 100% mobile phase B (100% ethanol containing 1 mM ammonium acetate) over 14 min, and held at 100% B for 4 min. A multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) protocol was performed in the negative ion mode using a 4000 Q-Trap hybrid triple quadrupole linear ion-trap mass spectrometer equipped with a Turbo V ion source (AB-Sciex, Foster City, CA). The MS settings were as follows: curtain gas = 20 psi, ion source gas 1 = 20 psi, ion source gas 2 = 30 psi, ion spray = −4500 V, heater temperature = 350°, Interface Heater = ON, declustering potential = −40 V, entrance potential = −10 V, and collision exit potential = −5 V. The voltage used for collision-induced dissociation was −40 V. For the MRM pairs, the precursor ions are the [M+acetate]− adduct ions of dolichol and polyprenol species, and the product ions are the acetate ions (m/z 59).

Data availability

All the reagents and data described in this paper are freely available upon request to the corresponding author.

Results

SRT1 is required for outer spore wall formation

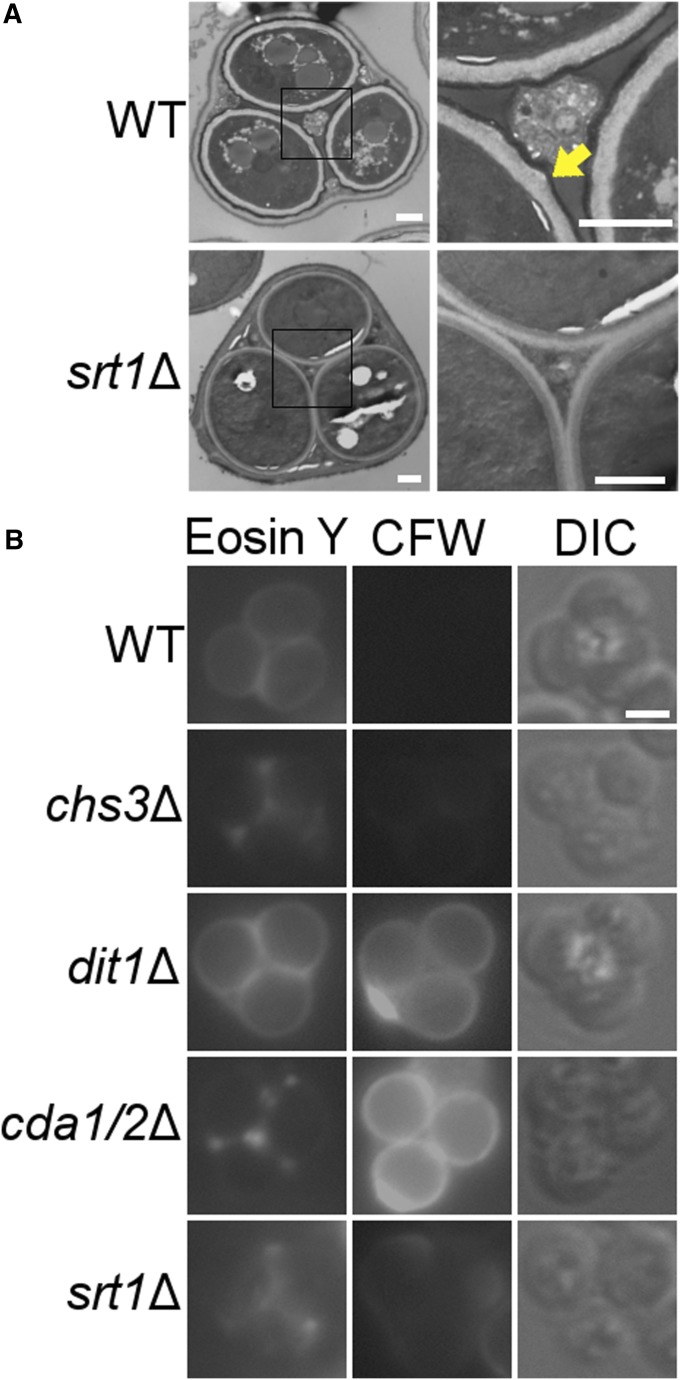

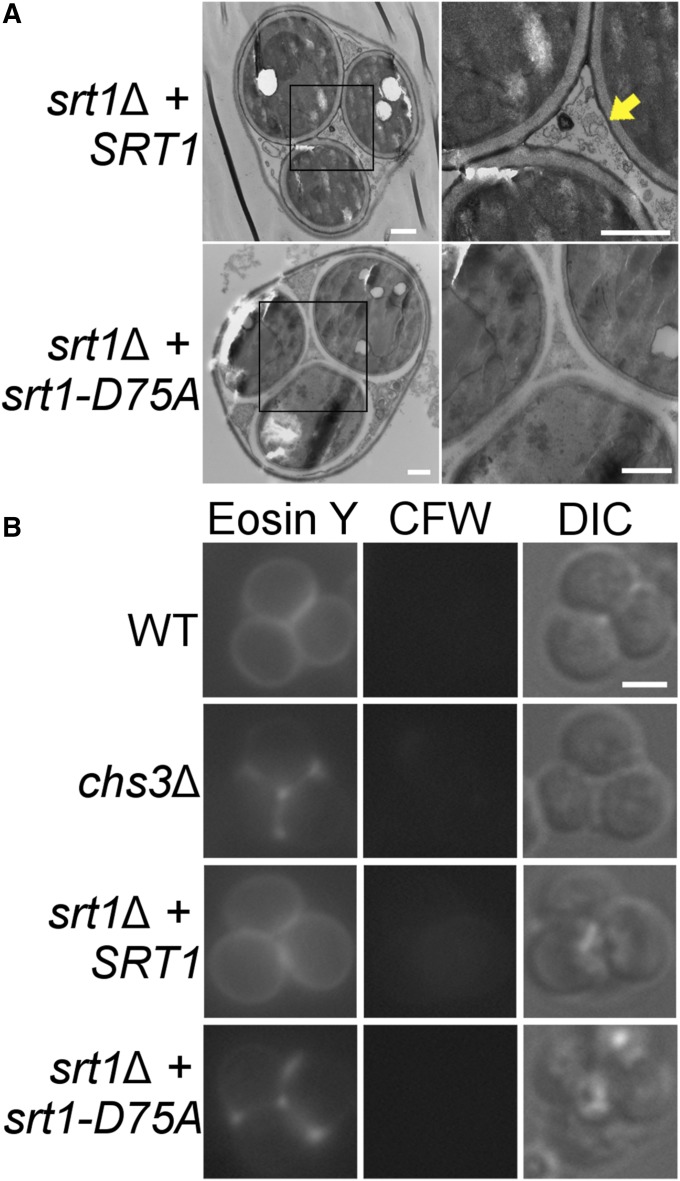

Previous work has demonstrated that SRT1 is required to make zymolyase-resistant spores, suggesting it is involved in either spore or spore wall formation (Deutschbauer et al. 2002; Enyenihi and Saunders 2003; Marston et al. 2004). The former possibility was ruled out by the observation that srt1∆ diploids formed asci at a frequency comparable to wild type (70.8% ±4.1 asci in wild type vs. 73.7% ±5.6 in srt1∆). However, light microscopy does not have the resolution to detect spore wall defects, so TEM was used to compare the spore walls from wild-type and srt1∆ spores. As previously reported, wild-type spores contained both the lightly staining mannan and β-glucan inner spore wall layers, as well as the more darkly staining outer chitosan and dityrosine layers (Lynn and Magee 1970) (Figure 1A). In contrast, 100% of srt1∆ spores lacked the chitosan and dityrosine layers (Figure 1A). This phenotype closely resembles that observed for mutants deficient in the production or assembly of the chitosan layer, such as chs3∆ or cda1∆ cda2∆ (Pammer et al. 1992; Christodoulidou et al. 1999), suggesting that SRT1 is required for chitosan synthesis.

Figure 1.

Cytological analysis of spore walls in srt1∆ and mutants defective in forming the chitosan layer. (A) Electron micrographs of wild-type (WT; AN120) and srt1∆ (RHY19) spores. Bar, 500 nm. Black squares in the left panels indicate areas shown in close-up in the right panels. The yellow arrow highlights the darkly staining chitosan and dityrosine layers. (B) Spores of wild type (AN120), chs3Δ (AN262), dit1Δ (AN264), cda1∆ cda2Δ (CL50), and srt1Δ (AN512) stained with Eosin Y or CFW. “DIC” indicates transmitted light images taken by differential interference contrast microscopy. Bar, 2 µm.

The absence of the chitosan layer (and therefore also the dityrosine layer) can occur due either to a failure to synthesize chitin (e.g., chs3∆) or failure to assemble chitin into a chitosan layer, (e.g., cda1∆ cda2∆) (Pammer et al. 1992; Christodoulidou et al. 1996, 1999). These two possibilities can be differentiated using the stains CFW and Eosin Y (Lin et al. 2013). Eosin Y specifically stains chitosan, while CFW stains both chitosan and chitin, but has difficulty penetrating the dityrosine layer of a wild-type spore (Tachikawa et al. 2001; Baker et al. 2007). As such, wild-type spores stain in a solid ring around the spore by Eosin Y but poorly by CFW (Figure 1B). A mutant that does not produce the dityrosine layer, such as dit1∆, stains in a solid ring with both dyes, while spores deficient in chitin production, such as chs3∆, do not stain well with either dye (though Eosin Y staining can be seen in patches in the ascal cytoplasm between the spores) (Figure 1B). Spores that produce chitin but fail to convert it to chitosan, such as cda1∆ cda2∆, stain brightly in rings with CFW, but Eosin Y is restricted to the ascal cytoplasm (Figure 1B). In these assays, srt1∆ spores phenocopy chs3∆ (Figure 1B). That is, they are not clearly stained by CFW, and Eosin Y shows only patchy staining in the ascus, suggesting that the srt1∆ mutant lacks the outer spore wall layers due to a defect in chitin synthesis.

Sporulating cells display an SRT1-dependent increase in cis-prenyltransferase activity and long-chain polyisoprenoids

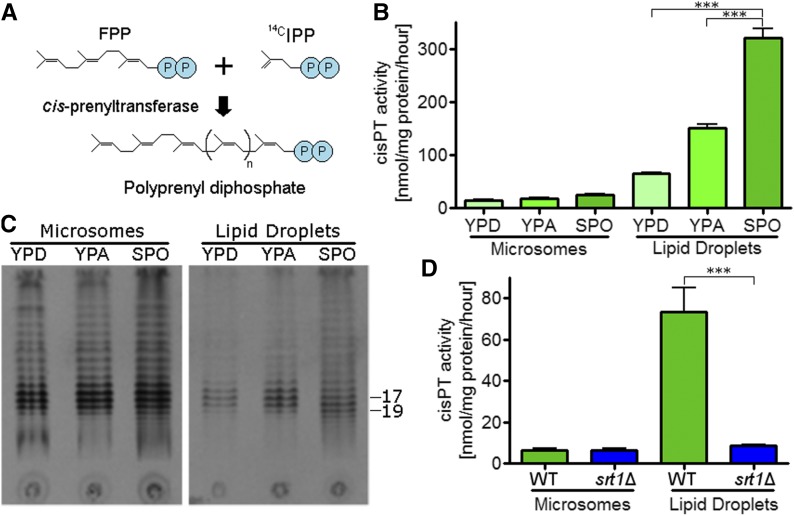

The outer spore wall defect of srt1∆, along with a lack of phenotype for the deletion in vegetative cells, suggests that the Srt1-Nus1 cis-prenyltransferase functions primarily during sporulation. cis-Prenyltransferase activity can be monitored in vitro using an enzyme assay in which the enzyme serially attaches 14C labeled IPP units to FPP (Figure 2A) (Grabińska et al. 2016). cis-Prenyltransferase activity was compared between microsomal and lipid droplet fractions derived from either vegetative cells grown in rich medium containing either glucose or acetate as the carbon source (YPD and YPA, respectively) or sporulating cells. Cis-Prenyltransferase activity was low in the microsomal fractions under all three conditions (Figure 2B). In contrast, activity was significantly increased in the lipid droplet fraction when cells were grown in acetate compared to glucose, and activity was further increased by incubation in SPO medium (which is 2% KOAc) (Figure 2B). The reaction products were visualized using thin-layer chromatography and autoradiography, which revealed that the most prominent species in both the microsome and lipid droplet fractions from vegetative cells were centered on 16–17 isoprene units, consistent with Rer2 being the predominant synthase (Sato et al. 2001) (Figure 2C). By contrast, a shift toward longer species (∼19 units) was observed specifically in the lipid droplet fraction from sporulating cells. The fact that Srt1-Nus1 generates longer polyprenoids than Rer2-Nus1, and that Srt1 localizes to lipid droplets in sporulating cells (Sato et al. 2001; Schenk et al. 2001; Lam et al. 2014), suggested that the sporulation-specific cis-prenyltransferase activity observed in lipid droplets is due to SRT1. This idea was confirmed by the observation that the sporulation-specific increase in cis-prenyltransferase activity observed in the lipid droplets was eliminated in srt1∆ (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Cis-Prenyltransferase activity in glucose and acetate medium in vegetative and sporulating cells. (A) In vitro reaction catalyzed by cis-prenyltransferase. 14C-labeled IPP units are serially attached to an FPP molecule to generate polyprenyl diphosphate containing variable numbers of IPP units (indicated by n). (B) Extracts were made from wild-type (RHY25) cells grown in YPD for 48 hr, grown in YPA until the OD600 reached ∼2, or incubated in SPO medium for 7 hr. Extracts were separated into microsomal and lipid droplet fractions and assayed for cis-prenyltransferase activity. Asterisks (***) note significant differences between the samples indicated by brackets (P < 0.001) by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test. Error bars show SE. Activities shown are the averages of three experiments. (C) Autoradiogram of thin layer chromatography separation of the reaction products from (A). The position of species with 17 and 19 isoprene unit species are indicated. (D) Cis-Prenyltransferase activity from extracts of wild-type (AN120) and srt1∆ (RHY19) cells incubated in SPO medium measured as in (A). Asterisks (***) note significant differences between the samples indicated by brackets (P < 0.001) by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test. Error bars show SE.

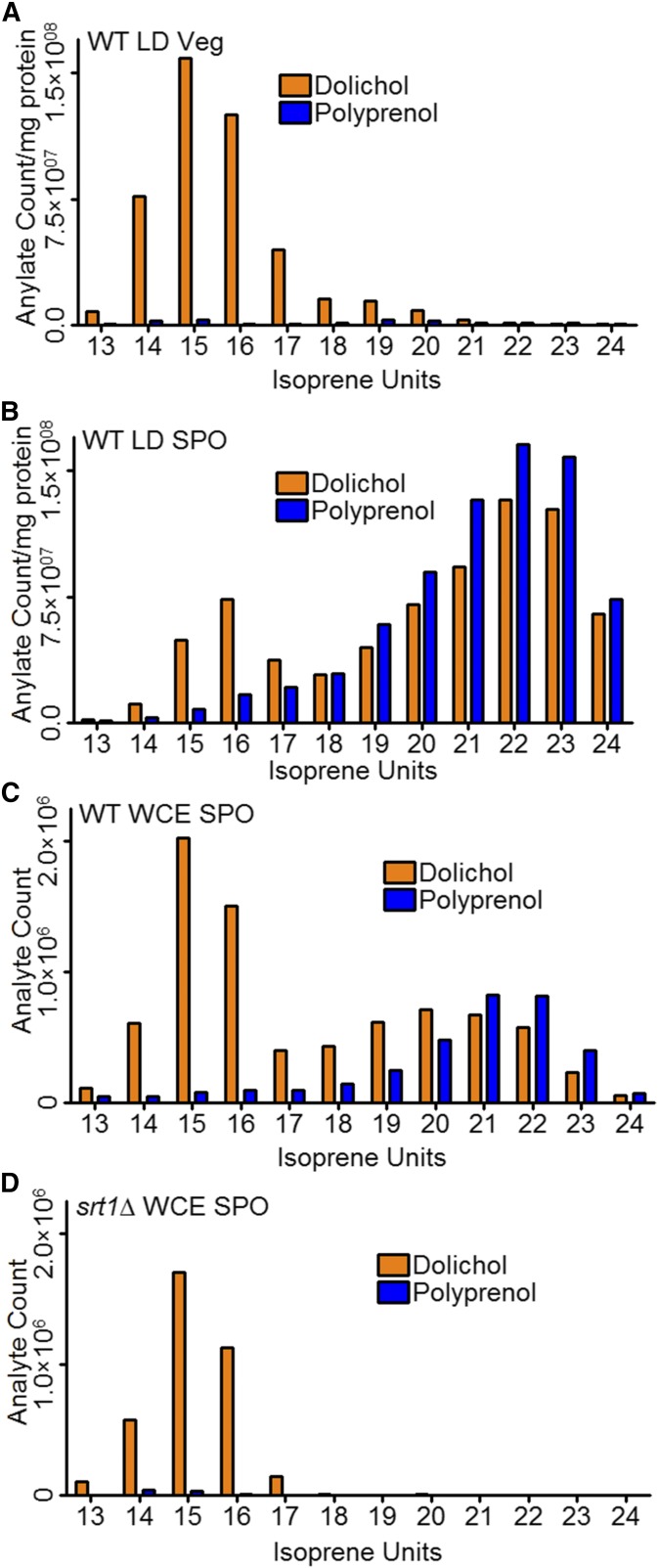

Given that Srt1-Nus1 is the predominant cis-prenyltransferase activity in sporulating cells, the levels of long-chain polyisoprenoids should be increased in sporulating cells compared to vegetative cells. This is indeed the case. The distribution of both dolichol and polyprenols containing different numbers of isoprene units present in lipid droplets from either vegetative or sporulating cells was determined using LC-MS. In lipid droplets from vegetative cells, the predominant isoprenoids were dolichols of 14–17 repeats (Figure 3A). By contrast, in sporulating cells the predominant species were longer (21–23 repeats) (Figure 3B). Moreover, the longer polyprenols were not efficiently converted to dolichol, as has been reported previously for Srt1 products (Sato et al. 2001). To determine whether the increased amounts of long-chain isoprenoids seen in sporulating cells are SRT1-dependent, whole cell lysates of sporulating cultures of wild-type and srt1∆ cells were assayed by LC-MS. While 14–17 unit dolichols were present in both cultures, the long-chain polyprenols and dolichols were absent in srt1∆ cells (Figure 3, C and D). Together, these results demonstrate an SRT1-mediated increase of long-chain polyisoprenoids in lipid droplets during sporulation, which may be linked with the requirement for SRT1 in outer spore wall formation.

Figure 3.

Various dolichol and polyprenol species isolated from lipid droplets in vegetative and sporulating cells. (A) The distribution of dolichol and polyprenol molecules containing different numbers of isoprene units was determined by LC-MS analysis of lipid droplet (LD) fractions from wild-type (WT) (AN120) cells grown in YPD for 48 hr (Veg), normalized against the total protein present in the fraction. (B) As in (A), except using sporulating cells incubated in SPO medium for 7 hr. (C) As in (A), except using whole cell extracts (WCE) of WT (AN120) cells incubated in SPO medium for 7 hr. (D) As in (D), except using WCE of srt1∆ cells (RHY19).

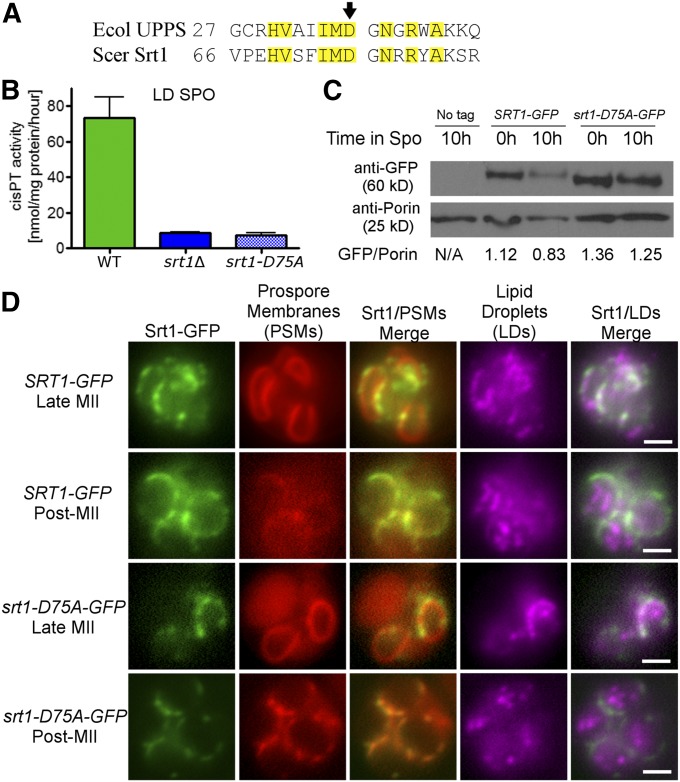

The cis-prenyltransferase activity of Srt1 is necessary for outer spore wall formation

SRT1-dependent polyprenols increase during sporulation and SRT1 is required for making the chitosan layer of the outer spore wall, raising the possibility that polyprenols are necessary for formation of the chitosan layer. This hypothesis was tested by phenotypically characterizing diploids containing an allele of SRT1 that encodes a catalytically inactive version of the enzyme. Aspartate (D) at position 27 of the E. coli cis-prenyltransferase undecaprenyl pyrophosphate synthase (UPPS) is required for catalysis (Pan et al. 2000). Alignment of the UPPS and Srt1 protein sequences identified D75 of Srt1 as the cognate residue for UPPS D27 (Figure 4A). (Liang et al. 2002). Measurements of cis-prenyltransferase activity in lipid droplets from sporulating cells for SRT1, srt1∆, and srt1-D75A diploids showed that srt1∆ and srt1-D75A both lack this activity, indicating that the D75A mutation creates a null phenotype with regard to enzyme activity (Figure 4B). Immunoblot analysis of GFP-tagged versions of Srt1 and Srt1-D75A demonstrated that the reduction in activity observed for srt1-D75A is not due to protein instability (Figure 4C). In sporulating cells, Srt1 is localized to lipid droplets associated with prospore membranes (Lam et al. 2014). To compare the localization of the wild-type and mutant proteins, the prospore membrane marker Spo2051-91-RFP (Suda et al. 2007) was introduced into diploids carrying either SRT1-GFP or srt1-D75A-GFP. In addition, sporulating cells were stained with the hydrophobic blue fluorescent marker, monodansylpentane, to visualize lipid droplets (Yang et al. 2012; Currie et al. 2014), and all three markers were detected by fluorescence microscopy. As previously described, Srt1-GFP was found in puncta along the extending prospore membrane (Lam et al. 2014), and these puncta also stained with the lipid droplet marker (Figure 4D). In post-MII cells (indicated by large, round, prospore membranes), Srt1-GFP fluorescence was seen in patches around the outside of the spore. These patches no longer colocalized with the lipid droplet dye, consistent with the disappearance of lipid droplets outside of the prospore membrane after closure (Figure 4D) (Ren et al. 2014). The same patterns were observed for Srt1D75A-GFP; thus, the mutant protein is inactive but stable and properly localized. The srt1-D75A mutant is therefore a useful tool to examine which phenotypes of SRT1 are dependent on its enzymatic activity.

Figure 4.

A catalytic site mutant of Srt1. (A) Alignment of E. coli (Ecol) undecaprenyl pyrophosphate synthase (UPPS) and S. cerevisiae (Scer) Srt1 protein sequences. Numbers indicate the amino acid position in the protein of the first amino acid shown in the sequence. Identical residues are highlighted in yellow; the black arrow indicates the aspartate residue mutated in srt1-D75A. (B) LD fractions were prepared from sporulating cells of wild type (AN120), srt1Δ (RHY19), or srt1-D75A (RHY19-P2) and assayed for cis-prenyltransferase activity. (C) Lysates of wild-type (AN120) cells carrying no plasmid, or plasmids expressing SRT1-GFP or srt1-D75A-GFP were prepared at the time of transfer (0 hr) or 10 hr after transfer to SPO medium. Western blots were performed using anti-GFP antibodies or anti-Porin antibodies as a loading control. The ratio of Srt1:Por1 signal is shown below. (D) Sporulating wild-type (AN120) cells expressing SRT1-GFP or srt1-D75A-GFP (green) and the prospore membrane marker Spo2051-91-RFP (red), were stained with the LD marker monodansylpentane (violet) and examined by fluorescence microscopy. Representative cells from different stages are shown. Bar, 2 µm.

SRT1-dependent cis-prenyltransferase activity is required for generation of the chitosan layer in spores. TEM analysis of srt1-D57A spores revealed that the darkly staining material indicative of the chitosan and dityrosine layers of the spore wall was absent, similar to srt1∆ (compare Figure 1A and Figure 5A). The absence of both chitin and chitosan was shown by the failure to observe any staining with either CFW or Eosin Y (Figure 5B). These observations demonstrate that Srt1-generated polyprenols are required specifically for the formation of the chitosan layer of the outer spore wall.

Figure 5.

Analysis of spore walls of srt1-D75A spores. (A) Electron micrographs of srt1Δ cells transformed with integrating plasmids carrying SRT1 (RHY19-P1; top panels) or srt1-D75A (RHY19-P2; bottom panels). Yellow arrow indicates the dark staining outer spore wall, areas are in close-up are indicated by black boxes. Bar, 500 nm. (B) Spores of WT (AN120), chs3∆ (AN264), srt1∆ expressing SRT1 (RHY 19-P1), or srt1∆ expressing srt1-D75A (RHY19-P2), were stained with Eosin Y and CFW. “DIC” indicates transmitted light images taken by differential interference contrast microscopy. Bar, 2 μm.

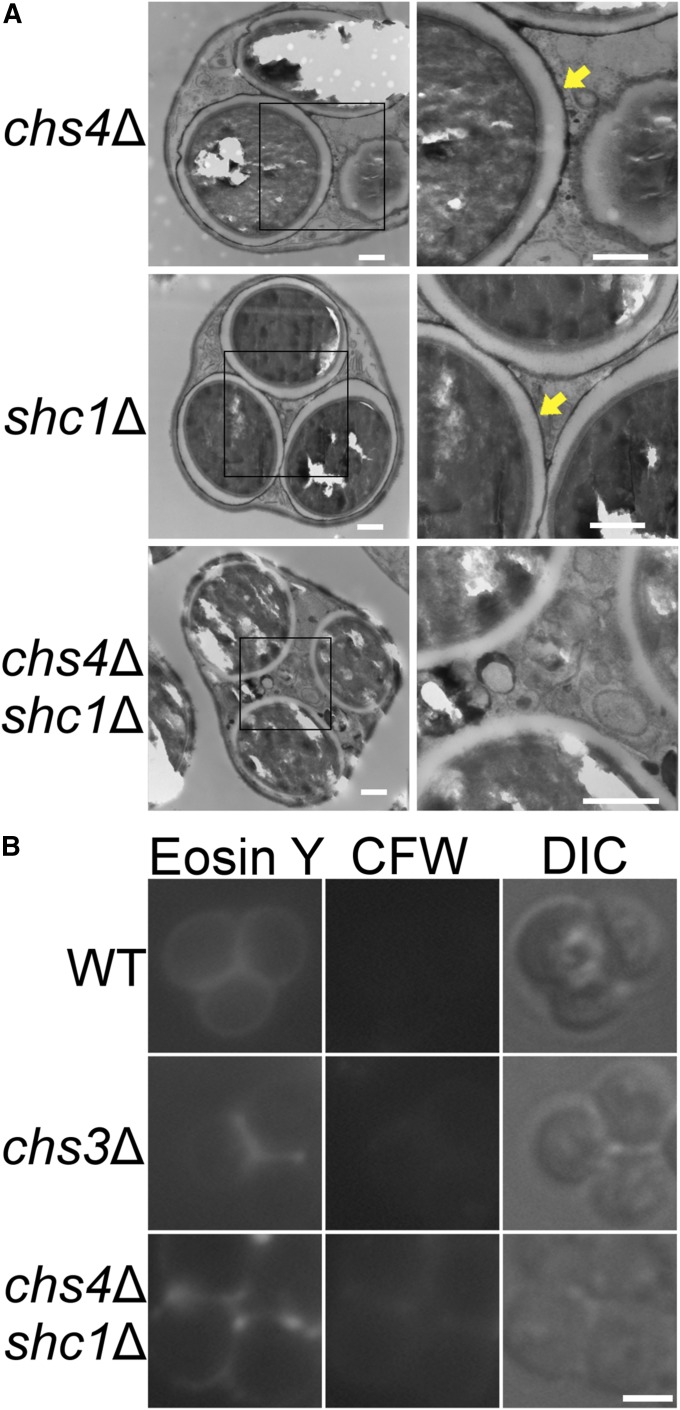

CHS4 and SHC1 act redundantly to promote outer spore wall formation

Synthesis of the chitosan layer of the spore wall requires first that chitin be generated by the chitin synthase, Chs3 (Pammer et al. 1992). In vegetative cells, Chs3 activity is controlled by the allosteric activator, Chs4 (DeMarini et al. 1997; Ono et al. 2000; Kozubowski et al. 2003). In sporulating cells, there is a sporulation-specific paralog of Chs4 called Shc1 (Sanz et al. 2002). CHS4 and SHC1 function redundantly during sporulation to make the chitosan layer of the spore wall—i.e., spore walls were normal in either single mutant while both the chitosan and dityrosine layers were absent in the chs4∆ shc1∆ double mutant (Figure 6A). These cytological phenotypes were confirmed by CFW and Eosin Y staining in which the chs4Δ shc1Δ spores resemble chs3∆ (Figure 6B). The discovery that eliminating known regulators of Chs3 activity (chs4∆ shc1∆) has the same outer spore wall defect as srt1-D57A suggests a role for polyprenols in the regulation of chitin synthase activity specifically in sporulating cells.

Figure 6.

Analysis of spore walls in chs4∆, shc1∆, and chs4∆ shc1∆ cells. (A) Electron micrographs of chs4∆ (RHY29), shc1∆ (AN270), or chs4∆ shc1∆ (RHY39) spores. Bar, 500 nm. Black squares in left panels indicate areas in close-up view in the right panels. The yellow arrows highlight the darkly staining chitosan and dityrosine layers. (B) Spores of wild type or chs4∆ shc1∆ stained with Eosin Y or CFW. “DIC” indicates transmitted light images taken by differential interference contrast microscopy. Bar, 2 µm.

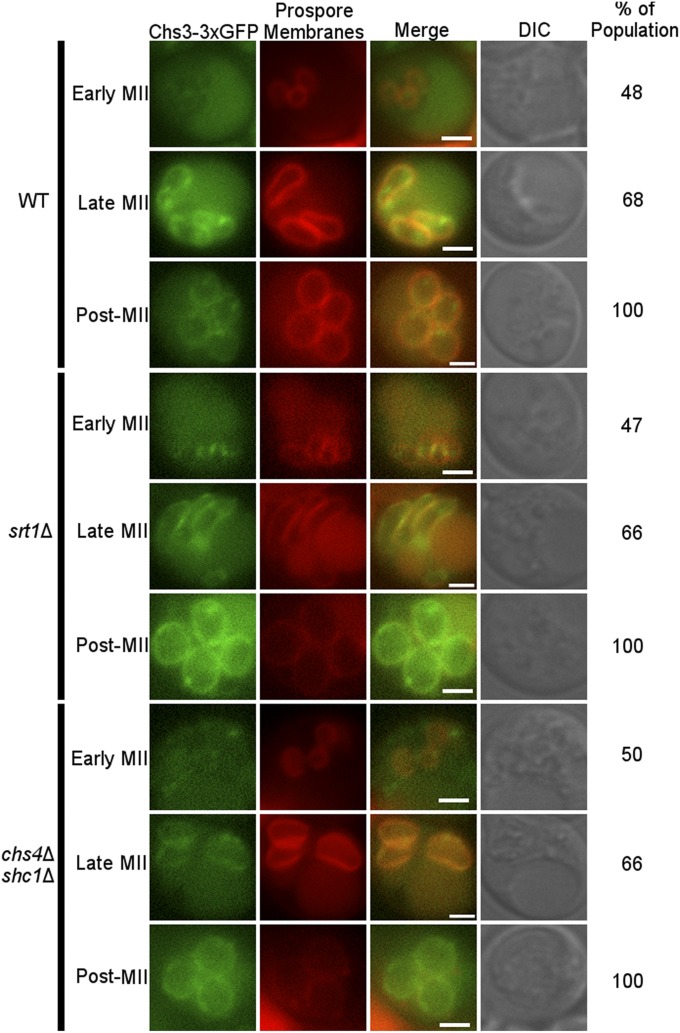

SRT1 is not required for Chs3 localization to the prospore membrane

In vegetative cells, Chs3 activity is controlled, in part, by the regulated delivery of the protein to its site of action at the bud neck (Kozubowski et al. 2003). One mechanism by which Srt1 could facilitate Chs3 activity would be to promote the localization of Chs3 to the prospore membrane. This idea was tested by tagging Chs3 with 3xsfGFP in the genome of wild type, srt1Δ, and chs4Δ shc1Δ cells that contained Spo2051-91-RFP as a prospore membrane marker, and examining cells either at early, late, or post-MII for the colocalization of these markers.

Prospore membranes form and expand through a series of stages identifiable by the size and shape of the membrane (Diamond et al. 2009). At early MII in wild-type cells, about half of the prospore membranes displayed Chs3-3xsfGFP fluorescence (Figure 7). As the prospore membranes expanded through meiosis, the fraction that displayed Chs3-3xsfGFP fluorescence increased so that post-MII, and prior to chitin synthesis, 100% of the membranes contained detectable levels of Chs3 (Figure 7) (Coluccio et al. 2004). These results argue against the idea that Chs3 activity is controlled primarily by regulation of its localization to prospore membranes during sporulation. In fact, the pattern and timing of delivery of Chs3-3xsfGFP to the prospore membrane was very similar in the wild-type, chs4∆ shc1∆, and srt1∆ diploids (Figure 7), suggesting that Srt1 may regulate instead the enzymatic activity of Chs3.

Figure 7.

Chs3 localization in sporulating cells. Sporulating wild-type (RHY16), srt1∆ (RHY44), and chs4∆ shc1∆ (RHY57) cells expressing Chs3-3xGFP (green) and the prospore membrane marker Spo2051-91-RFP (red) were examined by fluorescence microscopy. Representative cells in early MII, late MII, and postmeiosis are shown. Numbers at right indicate the percentage of cells at each stage with displaying Chs3-GFP localization at the prospore membrane. Bar, 2 µm.

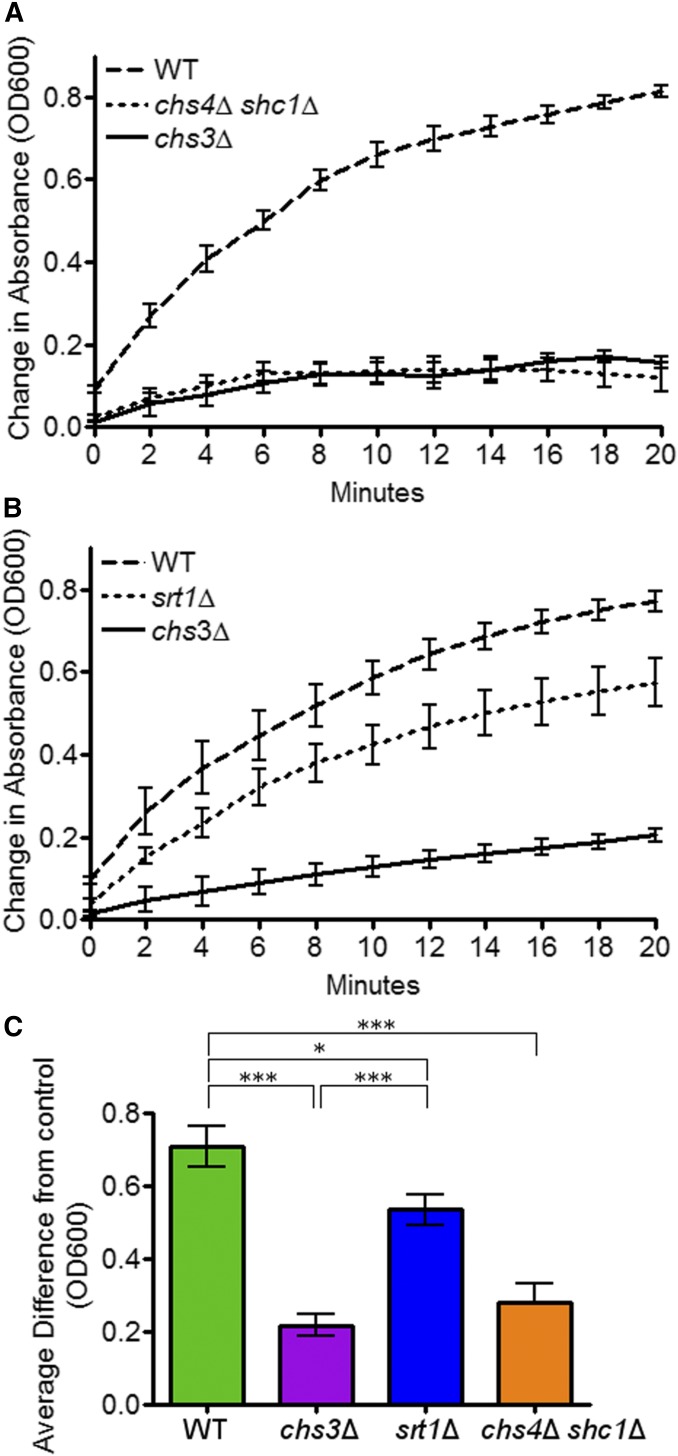

SRT1 promotes Chs3 activity in vitro

To test whether Srt1 regulates Chs3 activity in vitro, chitin synthase activity was measured in extracts from in srt1∆, chs4∆ shc1∆, chs3∆, and wild-type sporulating cells (Lucero et al. 2002). Each strain was incubated in SPO medium until at least 60% of cells in the culture displayed refractile spores, indicating a majority of cells had completed formation of the β-glucan layer of the spore wall (Coluccio et al. 2004). Extracts were made from each culture, and equivalent amounts of protein added to reaction buffer containing the Chs3 substrate UDP-GlcNAc in 96-well plates coated with a chitin-binding lectin. The reactions were incubated at 30° for 90 min to allow Chs3 to covalently join the GlcNAc sugars to form chitin. This chitin binds to the lectin coating the wells. The wells were then rinsed to remove Chs3 and unreacted UDP-GlcNAc and the treated with a lectin-coupled horseradish peroxidase that binds to the chitin to form a “lectin sandwich.” The amount of peroxidase bound is proportional to the amount of chitin synthesized (Lucero et al. 2002). The colorimetric horseradish peroxidase substrate, 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine, was then added to each well and the amount of peroxidase activity was measured using a spectrophotometer to measure the OD600 (Lucero et al. 2002). To control for the presence of chitin in the extracts or other forms of background, each extract was also incubated in wells lacking UDP-GlcNAc. The amount of chitin synthase activity was defined as the difference between the peroxidase activity in the wells with UDP-GlcNAc minus the peroxidase activity in the wells without UDP-GlcNAc.

Chitin synthase activity in the different strains was compared both as a function of time after addition of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (Figure 8, A and B), as well as at a 20 min endpoint (Figure 8C). Wild-type and chs3∆ extracts displayed a clear, statistically significant difference in chitin synthase activity (Figure 8) (Lucero et al. 2002). A significant reduction of activity was also seen in chs4Δ shc1Δ extracts, consistent with the known roles of these proteins as activators of Chs3 (Figure 8, A and C) (Ono et al. 2000; Sanz et al. 2002). The srt1∆ diploid exhibited a modest, but significant, decrease in activity compared to wild type (Figure 8, B and C). Although the decrease in chitin synthase activity is not as great as chs4∆ shc1∆, the fact that srt1∆ and chs4∆ shc1∆ both fail to make outer spore walls suggests that SRT1 is required to generate a threshold level of chitin synthase activity necessary for making the chitosan layer of the outer spore wall.

Figure 8.

Chs3 activity in various mutants in sporulating cells. Chitin synthase activity assays were performed as a function of time after addition of the horseradish peroxidase substrate using extracts from sporulating cultures as described in Materials and Methods. Assays were performed in quadruplicate at 2-min intervals over a 20-min time-course six independent times. Representative time courses are shown. (A) Wild-type (AN210), chs3∆ (A262), and chs4∆ shc1∆ (RHY26). (B) Wild type, chs3∆ and srt1∆ (RHY19). (C) End point measurements of Chs3 activity (20-min time point) averaged across at least three experiments run in quadruplicate using the same strains as in (A) and (B). Error bars show SE. Asterisks indicate significant difference (*P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001) assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD post hoc test.

Discussion

In many systems, dynamic lipid droplets have emerged as a means to deliver lipids to specific locations in the cell (Kohlwein et al. 2013; Wang 2015). While cells that fail to produce triglycerides or sterol esters—the major components of lipid droplets—still form spores, cells that do not form lipid droplets at all show severe sporulation defects, often producing dead spores or no spores (Hsu et al. 2017). This suggests that, during sporulation, lipid droplets act as carriers for additional proteins or lipids whose delivery to the prospore membrane or spore wall is important for spore formation. In the case of spore wall assembly, the lipid droplets are likely acting as carriers of polyisoprenoids. In addition to Srt1, the Lds family proteins localize specifically to external lipid droplets during sporulation (Lin et al. 2013). Loss of these proteins also causes outer spore wall defects, though the defect is distinct from srt1∆ in that the chitosan layer is present (Lin et al. 2013). Thus, the lipid droplets may deliver additional factors that are important for outer spore wall assembly.

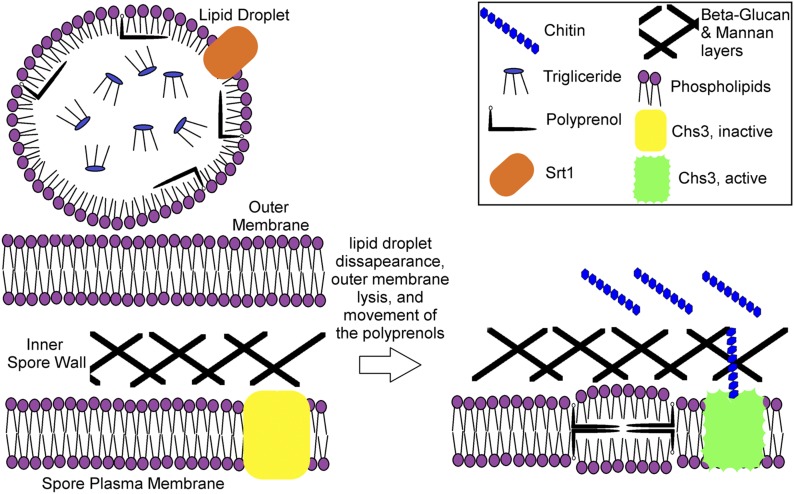

The lipid droplets on which Srt1 is localized disappear over the course of spore wall maturation, presumably because the neutral lipids are consumed, as evidenced by their reduction in size seen in TEM, the disappearance of staining with hydrophobic dyes, and the change in localization of proteins like Srt1 from these droplets to a distribution around the spore (Lin et al. 2013; Ren et al. 2014). As these droplets disappear, the polyisoprenoids in them must partition into a different hydrophobic environment. As synthesis of the β-glucan layer finishes, the outer membrane lyses (Coluccio et al. 2004) (Figure 9). Thus, the nearest cellular membrane to which the polyisoprenoids “released” from the lipid droplets could move to is the spore plasma membrane. We propose that the appearance of these long chain polyisoprenoids in the spore plasma membrane directly or indirectly activates the chitin synthase, Chs3, to make the chitin necessary for formation of the chitosan layer, thereby coordinating outer spore wall assembly with the completion of the inner spore wall (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Model for the role of polyprenols in activation of Chs3. During the early stages of spore wall assembly, LDs associated with the outer membrane accumulate high levels of polyprenols (left panel). As the inner spore wall layers form, the neutral lipids in these droplets are consumed and the outer membrane lyses leading to the partition of the polyprenols into the spore plasma membrane (right panel). The presence of polyprenols in the spore plasma membrane serves a signal, directly or indirectly, to activate Chs3.

There are several possible ways that delivery of polyisoprenoids to the spore plasma membrane might promote chitin synthesis. Given the well-characterized role of dolichols as sugar carriers for protein glycosylation (Burda and Aebi 1999; Loibl and Strahl 2013), one possibility is that SRT1-generated polyprenols play a similar role as sugar carriers for spore wall assembly. The explanation is unlikely, however, given that the mannan layer (which is composed of N- and O-mannosylated proteins) is properly formed in the srt1Δ mutant, indicating there is no major deficit in protein glycosylation. Also, the sugar donor for chitin synthesis is the cytoplasmic sugar nucleotide UDP-GlcNAc (Cabib et al. 1983; Pammer et al. 1992), so there is no need for dolichol to act as a sugar carrier in this reaction. It is noteworthy that in brine shrimp, it has been suggested that the synthesis of chitin may be primed by an initial GlcNAc residue linked to dolichol (Horst 1983). While no such requirement has been reported for yeast chitin synthases, it is possible that the long-chain polyprenols produced by Srt1 could be conjugated to GlcNAc and act as primers for Chs3 to begin synthesis at the spore plasma membrane. Dolichol not only acts as a carrier for the sugars in N-linked glycosylation, but the lipid is important for allowing the dolichol-linked sugars to flip from the cytosolic to luminal side of the ER membrane (Sanyal and Menon 2010; Perez et al. 2015). The transmembrane domains of the chitin synthase enzyme itself are proposed to form a pore to allow for translocation of the chitin chains across the plasma membrane, and there is structural data from related bacterial cellulose synthases to support this model (Cabib et al. 1983; Morgan et al. 2013; Gohlke et al. 2017). However, it is possible that polyprenols could facilitate translocation of the chains through their effects on properties of the membrane.

Alternatively, the presence of polyisoprenoids in the spore plasma membrane might directly activate Chs3. Polyprenols can affect the shape and fluidity of membrane bilayers in in vitro experiments (Valtersson et al. 1985). Recently it was reported that polyprenols influence photosynthetic performance in vivo through their modulation of thylakoid membrane dynamics in the chloroplast (Akhtar et al. 2017). For instance, Chs3 oligomerization is important for its chitin synthase activity (Gohlke et al. 2017), and this could be affected by the properties of the membrane. Finally, the effect on Chs3 activity might be indirect. Polyisoprenoids in the prospore membrane could act in a signaling pathway that regulates Chs3 activity. Mutations in two other genes, MUM3 and OSW1, display similar phenotypes as srt1∆ (Coluccio et al. 2004), raising the possibility that they may act with SRT1 in such a pathway.

While the precise mechanism by which polyisoprenoids lead to activation of Chs3 remains to be determined, our results reveal a function for these lipids separate from their known role in protein glycosylation. Dolichol and other polyprenols are present in all kingdoms of life and, in eukaryotic cells, are found in membrane compartments outside of the ER where glycosylation occurs (Swiezewska and Danikiewicz 2005; Jones et al. 2009). Any mechanism by which Srt1-generated polyprenols promote spore wall formation may therefore be conserved in other fungi for activation of chitin synthase or, potentially, in other organisms for other, unrelated, processes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Leor Needleman, Gang Zhao, and Bruce Futcher for plasmids, and Susan Van Horn and the Stony Brook Center for Microscopy for assistance with TEM. They also thank Ed Luk and Joshua Rest for the use of plate readers, Nancy Hollingsworth for use of theFast-Prep Machine, and Xiangyu Chen for assistance with western blotting. They are grateful to members of the Neiman and Hollingsworth laboratories for advice and discussion and to Nancy Hollingsworth for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01 GM072540 to A.M.N., and grants R01 HL64793, R01 HL61371 and HL133018 from the NIH and the Leducq Foundation (MicroRNA-based Therapeutic Strategies in Vascular Disease network) to W.C.S.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: J. Heitman

Literature Cited

- Abu-Qarn M., Eichler J., Sharon N., 2008. Not just for Eukarya anymore: protein glycosylation in Bacteria and Archaea. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 18: 544–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar T. A., Surowiecki P., Siekierska H., Kania M., Van Gelder K., et al. , 2017. Polyprenols are synthesized by a plastidial cis-prenyltransferase and influence photosynthetic performance. Plant Cell 29: 1709–1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athenstaedt K., 2010. Isolation and characterization of lipid particles from yeast, pp. 4223–4229 in Handbook of Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology, edited by Timmis K. N. Springer, Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- Bahler J., Wu J. Q., Longtine M. S., Shah N. G., McKenzie A., III, et al. , 1998. Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast 14: 943–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker L. G., Specht C. A., Donlin M. J., Lodge J. K., 2007. Chitosan, the deacetylated form of chitin, is necessary for cell wall integrity in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot. Cell 6: 855–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briza P., Ellinger A., Winkler G., Breitenbach M., 1988. Chemical composition of the yeast ascospore wall. The second outer layer consists of chitosan. J. Biol. Chem. 263: 11569–11574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briza P., Breitenbach M., Ellinger A., Segall J., 1990a Isolation of two developmentally regulated genes involved in spore wall maturation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 4: 1775–1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briza P., Ellinger A., Winkler G., Breitenbach M., 1990b Characterization of a DL-dityrosine-containing macromolecule from yeast ascospore walls. J. Biol. Chem. 265: 15118–15123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burda P., Aebi M., 1999. The dolichol pathway of N-linked glycosylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1426: 239–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers B., 1981. Cytology of the yeast life cycle, pp. 59–96 in The Molecular Biology of the Yeast Saccharomyces: Life Cycle and Inheritance, edited by Strathern J. N., Jones E. W., Broach J. R. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Cabib E., Bowers B., Roberts R. L., 1983. Vectorial synthesis of a polysaccharide by isolated plasma membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80: 3318–3321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B. H., Yang H. J., Chou H. Y., Chen G. C., Yang W. Y., 2017. Staining of lipid droplets with monodansylpentane. Methods Mol. Biol. 1560: 231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi W. J., Sburlati A., Cabib E., 1994. Chitin synthase 3 from yeast has zymogenic properties that depend on both the CAL1 and the CAL3 genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91: 4727–4730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulidou A., Bouriotis V., Thireos G., 1996. Two sporulation-specific chitin deacetylase-encoding genes are required for the ascospore wall rigidity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 31420–31425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulidou A., Briza P., Ellinger A., Bouriotis V., 1999. Yeast ascospore wall assembly requires two chitin deacetylase isozymes. FEBS Lett. 460: 275–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang J. S., Schekman R. W., 1996. Differential trafficking and timed localization of two chitin synthase proteins, Chs2p and Chs3p. J. Cell Biol. 135: 597–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coluccio A., Bogengruber E., Conrad M. N., Dresser M. E., Briza P., et al. , 2004. Morphogenetic pathway of spore wall assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot. Cell 3: 1464–1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coluccio A. E., Rodriguez R. K., Kernan M. J., Neiman A. M., 2008. The yeast spore wall enables spores to survive passage through the digestive tract of Drosophila. PLoS One 3: e2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie E., Guo X., Christiano R., Chitraju C., Kory N., et al. , 2014. High confidence proteomic analysis of yeast LDs identifies additional droplet proteins and reveals connections to dolichol synthesis and sterol acetylation. J. Lipid Res. 55: 1465–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMarini D. J., Adams A. E., Fares H., De Virgilio C., Valle G., et al. , 1997. A septin-based hierarchy of proteins required for localized deposition of chitin in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell wall. J. Cell Biol. 139: 75–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutschbauer A. M., Williams R. M., Chu A. M., Davis R. W., 2002. Parallel phenotypic analysis of sporulation and postgermination growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 15530–15535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A. E., Park J.-S., Inoue I., Tachikawa H., Neiman A. M., 2009. The anaphase promoting complex targeting subunit Ama1 links meiotic exit to cytokinesis during sporulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 20: 134–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enyenihi A. H., Saunders W. S., 2003. Large-scale functional genomic analysis of sporulation and meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 163: 47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaever G., Chu A. M., Ni L., Connelly C., Riles L., et al. , 2002. Functional profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature 418: 387–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson D. G., Young L., Chuang R. Y., Venter J. C., Hutchison C. A., III, et al. , 2009. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat. Methods 6: 343–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohlke S., Muthukrishnan S., Merzendorfer H., 2017. In vitro and in vivo studies on the structural organization of Chs3 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18: 702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabińska K., Sosińska G., Orłowski J., Swiezewska E., Berges T., et al. , 2005. Functional relationships between the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cis-prenyltransferases required for dolichol biosynthesis. Acta Biochim. Pol. 52: 221–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabińska K. A., Cui J., Chatterjee A., Guan Z., Raetz C. R., et al. , 2010. Molecular characterization of the cis-prenyltransferase of Giardia lamblia. Glycobiology 20: 824–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabińska K. A., Park E. J., Sessa W. C., 2016. cis-Prenyltransferase: new insights into protein glycosylation, rubber synthesis, and human diseases. J. Biol. Chem. 291: 18582–18590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Z., Eichler J., 2011. Liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry of dolichols and polyprenols, lipid sugar carriers across evolution. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1811: 800–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horst M. N., 1983. The biosynthesis of crustacean chitin. Isolation and characterization of polyprenol-linked intermediates from brine shrimp microsomes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 223: 254–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu T. H., Chen R. H., Cheng Y. H., Wang C. W., 2017. Lipid droplets are central organelles for meiosis II progression during yeast sporulation. Mol. Biol. Cell 28: 440–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto M. A., Fairclough S. R., Rudge S. A., Engebrecht J., 2005. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Sps1p regulates trafficking of enzymes required for spore wall synthesis. Eukaryot. Cell 4: 536–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin L., Zhang K., Sternglanz R., Neiman A. M., 2017. Predicted RNA binding proteins Pes4 and Mip6 regulate mRNA levels, translation, and localization during sporulation in budding yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 37: e00408–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M. B., Rosenberg J. N., Betenbaugh M. J., Krag S. S., 2009. Structure and synthesis of polyisoprenoids used in N-glycosylation across the three domains of life. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1790: 485–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knop M., Siegers K., Pereira G., Zachariae W., Winsor B., et al. , 1999. Epitope tagging of yeast genes using a PCR-based strategy: more tags and improved practical routines. Yeast 15: 963–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlwein S. D., Veenhuis M., van der Klei I. J., 2013. Lipid droplets and peroxisomes: key players in cellular lipid homeostasis or a matter of fat—store ’em up or burn ’em down. Genetics 193: 1–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozubowski L., Panek H., Rosenthal A., Bloecher A., DeMarini D. J., et al. , 2003. A Bni4-Glc7 phosphatase complex that recruits chitin synthase to the site of bud emergence. Mol. Biol. Cell 14: 26–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreger-Van Rij N. J., 1978. Electron microscopy of germinating ascospores of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Arch. Microbiol. 117: 73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon M., Kwon E. J., Ro D. K., 2016. cis-Prenyltransferase and polymer analysis from a natural rubber perspective. Methods Enzymol. 576: 121–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam C., Santore E., Lavoie E., Needleman L., Fiacco N., et al. , 2014. A visual screen of protein localization during sporulation identifies new components of prospore membrane-associated complexes in budding yeast. Eukaryot. Cell 13: 383–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang P.-H., Ko T.-P., Wang A. H.-J., 2002. Structure, mechanism and function of prenyltransferases. Eur. J. Biochem. 269: 3339–3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C. P.-C., Kim C., Smith S. O., Neiman A. M., 2013. A highly redundant gene network controls assembly of the outer spore wall in S. cerevisiae. PLoS Genet. 9: e1003700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loibl M., Strahl S., 2013. Protein O-mannosylation: what we have learned from baker’s yeast. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1833: 2438–2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine M. S., McKenzie A., III, Demarini D. J., Shah N. G., Wach A., et al. , 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14: 953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucero H. A., Kuranda M. J., Bulik D. A., 2002. A nonradioactive, high throughput assay for chitin synthase activity. Anal. Biochem. 305: 97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn R. R., Magee P. T., 1970. Development of the spore wall during ascospore formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 44: 688–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marston A. L., Tham W. H., Shah H., Amon A., 2004. A genome-wide screen identifies genes required for centromeric cohesion. Science 303: 1367–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra C., Semino C. E., McCreath K. J., de la Vega H., Jones B. J., et al. , 1997. Cloning and expression of two chitin deacetylase genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 13: 327–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan J. L., Strumillo J., Zimmer J., 2013. Crystallographic snapshot of cellulose synthesis and membrane translocation. Nature 493: 181–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neiman A., 1998. Prospore membrane formation defines a developmentally regulated branch of the secretory pathway in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 140: 29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neiman A. M., 2011. Sporulation in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 189: 737–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neiman A. M., Katz L., Brennwald P. J., 2000 Identification of domains required for developmentally regulated SNARE function. Genetics 155: 1643–1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono N., Yabe T., Sudoh M., Nakajima T., Yamada-Okabe T., et al. , 2000. The yeast Chs4 protein stimulates the trypsin-sensitive activity of chitin synthase 3 through an apparent protein-protein interaction. Microbiology 146: 385–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pammer M., Briza P., Ellinger A., Schuster T., Stucka R., et al. , 1992. DIT101 (CSD2, CAL1), a cell cycle-regulated yeast gene required for synthesis of chitin in cell walls and chitosan in spore walls. Yeast 8: 1089–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J. J., Yang L. W., Liang P. H., 2000. Effect of site-directed mutagenesis of the conserved aspartate and glutamate on E. coli undecaprenyl pyrophosphate synthase catalysis. Biochemistry 39: 13856–13861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park E. J., Grabińska K. A., Guan Z., Stránecky V., Hartmannová H., et al. , 2014. Mutation of Nogo-B receptor, a subunit of cis-prenyltransferase, causes a congenital disorder of glycosylation. Cell Metab. 20: 448–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez C., Gerber S., Boileven J., Bucher M., Darbre T., et al. , 2015. Structure and mechanism of an active lipid-linked oligosaccharide flippase. Nature 524: 433–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J., Pei-Chen Lin C., Pathak M. C., Temple B. R. S., Nile A. H., et al. , 2014. A phosphatidylinositol transfer protein integrates phosphoinositide signaling with lipid droplet metabolism to regulate a developmental program of nutrient stress-induced membrane biogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 25: 712–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose M. D., Winston F., Hieter P., 1990. Methods in Yeast Genetics: A Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Course Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal S., Menon A. K., 2010. Stereoselective transbilayer translocation of mannosyl phophoryl dolichol by an endoplasmic reticulum flippase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107: 11289–11294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz M., Trilla J. A., Duran A., Roncero C., 2002. Control of chitin synthesis through Shc1p, a functional homologue of Chs4p specifically induced during sporulation. Mol. Microbiol. 43: 1183–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M., Sato K., Nishikawa S., Hirata A., Kato J., et al. , 1999. The yeast RER2 gene, identified by endoplasmic reticulum protein localization mutations, encodes cis-prenyltransferase, a key enzyme in dolichol synthesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19: 471–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M., Fujisaki S., Sato K., Nishimura Y., Nakano A., 2001. Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has two cis-prenyltransferases with different properties and localizations. Implication for their distinct physiological roles in dolichol synthesis. Genes Cells 6: 495–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk B., Rush J. S., Waechter C. J., Aebi M., 2001. An alternative cis-isoprenyltransferase activity in yeast that produces polyisoprenols with chain lengths similar to mammalian dolichols. Glycobiology 11: 89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw J. A., Mol P. C., Bowers B., Silverman S. J., Valdivieso M. H., et al. , 1991. The function of chitin synthases 2 and 3 in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell cycle. J. Cell Biol. 114: 111–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski R. S., Hieter P., 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122: 19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits G. J., van den Ende H., Klis F. M., 2001. Differential regulation of cell wall biogenesis during growth and development in yeast. Microbiology 147: 781–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suda Y., Nakanishi H., Mathieson E. M., Neiman A. M., 2007. Alternative modes of organellar segregation during sporulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot. Cell 6: 2009–2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiezewska E., Danikiewicz W., 2005. Polyisoprenoids: structure, biosynthesis and function. Prog. Lipid Res. 44: 235–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]