Abstract

Two major stumbling blocks exist in high-throughput sequencing (HTS) data analysis. The first is the sheer file size, typically in gigabytes when uncompressed, causing problems in storage, transmission, and analysis. However, these files do not need to be so large, and can be reduced without loss of information. Each HTS file, either in compressed .SRA or plain text .fastq format, contains numerous identical reads stored as separate entries. For example, among 44,603,541 forward reads in the SRR4011234.sra file (from a Bacillus subtilis transcriptomic study) deposited at NCBI’s SRA database, one read has 497,027 identical copies. Instead of storing them as separate entries, one can and should store them as a single entry with the SeqID_NumCopy format (which I dub as FASTA+ format). The second is the proper allocation of reads that map equally well to paralogous genes. I illustrate in detail a new method for such allocation. I have developed ARSDA software that implement these new approaches. A number of HTS files for model species are in the process of being processed and deposited at http://coevol.rdc.uottawa.ca to demonstrate that this approach not only saves a huge amount of storage space and transmission bandwidth, but also dramatically reduces time in downstream data analysis. Instead of matching the 497,027 identical reads separately against the B. subtilis genome, one only needs to match it once. ARSDA includes functions to take advantage of HTS data in the new sequence format for downstream data analysis such as gene expression characterization. I contrasted gene expression results between ARSDA and Cufflinks so readers can better appreciate the strength of ARSDA. ARSDA is freely available for Windows, Linux. and Macintosh computers at http://dambe.bio.uottawa.ca/ARSDA/ARSDA.aspx.

Keywords: transcriptomics, novel storage solution, quantifying expression of paralogous genes, sequence format, ARSDA

High-throughput sequencing (HTS) is now used not only in characterizing differential gene expression, but also in many other fields, where it replaces the traditional microarray approach. Ribosomal profiling, traditionally done through microarray (Arava et al. 2003; MacKay et al. 2004), is now almost exclusively done with deep sequencing of ribosome-protected segments of messages (Ingolia et al. 2009, 2011), although the results from the two approaches for ribosomal profiling are largely concordant (Xia et al. 2011). Similarly, EST-based (Rogers et al. 2012) and microarray-based (Pleiss et al. 2007) methods for detecting alternative splicing events and characterizing splicing efficiency is now replaced by HTS (Kawashima et al. 2014), especially by lariat sequencing (Awan et al. 2013; Stepankiw et al. 2015). The availability of HTS data has dramatically accelerated the test of biological hypotheses. For example, a recent study on alternative splicing (Vlasschaert et al. 2016) showed that skipping of exon 7 (E7) in human and mouse USP4 is associated with weak signals of splice sites flanking E7. The researchers predicted that, in some species where the splice site signals are strong, E7 skipping would disappear. This prediction is readily tested and confirmed with existing HTS data, i.e., E6-E8 mRNA was found in species with weak splice signals flanking E7, and E6-E7-E8 mRNA in species with strong splice signals flanking E7 (Vlasschaert et al. 2016).

In spite of the potential of HTS data in solving practical biological problems, severe underusage of HTS data has been reported (GB Editorial Team 2011). One major stumbling block in using the HTS data are the large file size. Among the 6472 HTS studies on human available at NCBI/DDBJ/EBI by April 14, 2016, 196 studies each contribute >1 Terabyte (TB) of nucleotide bases, with the top one contributing 86.4 TB. Few laboratories would be keen on downloading and analyzing this 86.4 TB of nucleotides, not to mention comparing this study to HTS data from other human HTS studies.

The explosive growth of HTS data in recent years has caused serious problems in data storage, transmission, and analysis (Leinonen et al. 2011; Kodama et al. 2012). Because of the high cost of maintaining such data, coupled with the fact that few researchers had been using such data, NCBI had planned the closure of the sequence read archive a few years ago (GB Editorial Team 2011), but continued the support only after DDBJ and EBI decided to continue their effort of archiving the data. The incident highlights the prohibitive task of storing, transmitting, and analyzing HTS data, and motivated the joint effort of both industry and academics to search for data compression solutions (Janin et al. 2014; Zhu et al. 2015b; Numanagic et al. 2016).

HTS data files do not need to be so huge. Take, for example, the characterized transcriptomic data for Escherichia coli K12 in the file SRR1536586.sra (where SRR1536586 is the SRA sequence file ID in NCBI/DDBJ/EBI). The file contains 6,503,557 sequence reads of 50 nt each, but 195,310 sequences are all identical (TGTTATCACGGGAGACACACGGCGGGTGCTAACGTCCGTCGTGAAGAGGG), all mapping exactly to sites 929–978 in E. coli 23S rRNA genes (the study did use the MICROBExpress Bacterial mRNA Enrichment Kit to remove the 16S and 23S rRNA, otherwise there would be many more). There are much more extreme cases. For example, one of the 12 HTS files from a transcriptomic study of E. coli (SRR922264.sra), contains a read with 1,606,515 identical copies among its 9,690,570 forward reads. There is no sequence information lost if all these 1,606,515 identical reads are stored by a single sequence with a sequence ID such as UniqueSeqX_1606515 (i.e., SeqID_CopyNumber format which I dub FASTA+ format with file type .fasP). Such storage scheme not only results in dramatic saving in data storage and transmission, but also leads to dramatic reduction in computation time in downstream data analysis. At present, all software packages for HTS data analysis will take the 1,606,515 identical reads separately, and search them individually against the E. coli genome (or target gene sequences such as coding sequences). The SeqID_CopyNumber storage scheme reduces the 1,606,515 searches to a single one.

A huge chunk of SRA data stored in NCBI/DDBJ/EBI consists of ribosome profiling data (Ingolia et al. 2009, 2011), which is obtained by sequencing the mRNA segment (∼30 bases) protected by the ribosome after digesting all the unprotected mRNA segments. Mapping these ribosome-protected segments to the genome allows one to know specifically where the ribosomes are located along individual mRNAs. In general, such data are essential to understand translation initiation, elongation, and termination efficiencies. For example, a short poly(A) segment with about eight or nine consecutive A immediately upstream of the start codon in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) genes is significantly associated with ribosome density and occupancy (Xia et al. 2011), confirming the hypothesis that short poly(A) upstream of the start codon facilitates the recruitment of translation initiation factors, but long poly(A) would bind to poly(A)-binding protein and interfere with cap-dependent translation. Sequence redundancy is high in such ribosomal profiling data and the FASTA+ format can lead to dramatic saving in the disk space of data storage and time in data transmission.

Aside from the file size problem, HST data analysis also suffers from the problem of how to allocate multiple-matched reads to paralogous genes (Trapnell et al. 2013; Rogozin et al. 2014). The commonly used options of ignoring such multiple-matched reads or allocating them equally among matched paralogous genes are unsatisfactory. The software ARSDA I present here offers solutions to both the problem of file size and the problem of read allocation to paralogous genes.

ARSDA

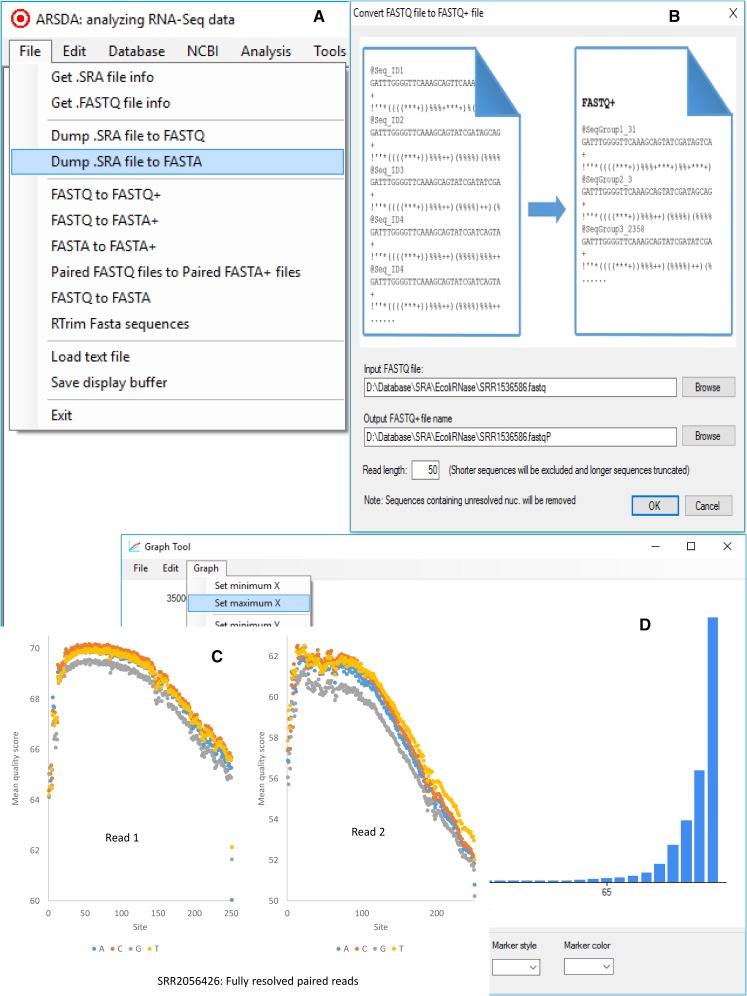

I developed software ARSDA (for Analyzing RNA-Seq Data, Figure 1A) to alleviate the problem associated with storage, transmission and analysis of HTS data. ARSDA can take input .SRA files or .fastq files of many gigabytes, build an efficient dictionary of unique sequence reads in a FASTA/FASTQ file, keep track of their copy numbers, and output them to a FASTA+ file in the SeqID_CopyNumber format (Figure 1B). Both fixed-length and variable-length sequences can be used as input. In addition, I have implemented functions in ARSDA to take advantage of the new sequence format to perform gene expression, with the main objective of demonstrating how much faster downstream data analysis can be done with data in FASTA+/FASTQ+ format. Furthermore, ARSDA includes a unique feature in assigning shared reads among paralogous genes that I will describe below. ARSDA also includes sequence visualization functions for global base-calling quality, per-read quality, and site-specific read quality (Figure 1, C and D), but these functions are also available elsewhere, e.g., FastQC (Andrews 2017) and NGSQC (Dai et al. 2010) and consequently will not be described further (but see the attached QuickStart.PDF). ARSDA includes nine programs in the BLAST and sratoolkit from NCBI that enhance part of ARSDA functions.

Figure 1.

User interface in ARSDA. (A) The menu system, with database creation under the “Database” menu, gene expression characterization under the “Analysis” menu, etc. (B) Converting a FASTQ/FASTA file to a FASTQ+/FASTA+ file. (C) Site-specific read quality visualization. (D) Global read quality visualization.

Converting HTS data to FASTA+/FASTQ+

The output from processing the SRR1536586.sra file (with part of the read matching output in Table 1) highlights two points. First, many sequences in the file are identical. Second, although the transcriptomic data characterized in SRR1536586 have undergone rRNA depletion by using Ambion’s MICROBExpress Bacterial mRNA Enrichment Kit (Pobre and Arraiano 2015), there are still numerous reads in the transcriptomic data that are from rRNA genes. This suggests that storing mRNA reads separately from rRNA reads can dramatically reduce file size because most researchers are not interested in the abundance of rRNAs.

Table 1. Part of read-matching output from ARSDA, with 195,310 identical reads matching a segment of large subunit (LSU) rRNA, 86,308 identical reads matching another segment of LSU rRNA, and so on.

| Gene | Ncopy | Gene | Ncopy |

|---|---|---|---|

| LSU rRNA | 195,310 | SSU rRNA | 30,417 |

| LSU rRNA | 86,308 | LSU rRNA | 29,508 |

| LSU rRNA | 58,400 | 5S rRNA | 28,187 |

| SSU rRNA | 47,323 | LSU rRNA | 24,982 |

| LSU rRNA | 45,695 | SSU rRNA | 23,286 |

| LSU rRNA | 36,258 | LSU rRNA | 19,991 |

| 5S rRNA | 33,674 | SSU rRNA | 19,268 |

Results generated from ARSDA analysis of the SRR1536586.sra file from NCBI.

While the conversion of FASTA/FASTQ files to FASTA+ files may take a few minutes, it needs to be done only once for data storage, and the resulting saving in storage space, internet traffic, and computation time in downstream data analysis is tremendous. The file size is 1.49 GB for the original FASTQ file derived from SRR1536586.sra, but is only 66 MB for the new FASTA+ file, both being plain text files.

I have applied ARSDA to reduce the file size of transcriptomic data from yeast (S. cerevisiae), nematode (Caenorhabditis elegans), fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster), zebrafish (Danio rerio), and mouse (Mus musculus), and deposited the resulting reduced data at coevol.rdc.uottawa.ca in the form of BLAST databases. BLAST reduces sequences further by representing tetranucleotides AAAA, AAAC, ..., TTTT by 0, 1, ..., 255 so that each tetranucleotide takes only 1 byte in storage. The sequence ID in these BLAST databases are in the form of SeqID_CopyNumber. These files reduce the computation time for quantifying gene expression from many hours to only a few minutes (>2 min for my Windows 10 PC with an i7-4770 CPU at 3.4 GHz and 16 GB of RAM). This eliminates one of the key bottlenecks in HTS data analysis (Liu et al. 2016), and would make it feasible for any laboratory to gain the power of HTS data analysis. I attach the gene expression characterized by ARSDA for the 4321 E. coli K12 coding sequences as Supplemental Material, File S1. A part of it is reproduced in Table 2.

Table 2. Partial output of gene expression, with the gene locus_tag (together with start and end sites) as Gene ID.

| Gene ID | SeqLen | Count | Count/Kb | FPKM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b0001|190_255 | 66 | 76 | 1151.515 | 389.894 |

| b0002|337_2799 | 2463 | 2963 | 1203.004 | 407.328 |

| b0003|2801_3733 | 933 | 1121 | 1201.501 | 406.819 |

| b0004|3734_5020 | 1287 | 1782 | 1384.615 | 468.82 |

| b0005|5234_5530 | 297 | 97 | 326.599 | 110.584 |

| b0006|C5683_6459 | 777 | 113 | 145.431 | 49.242 |

| b0007|C6529_7959 | 1431 | 143 | 99.93 | 33.836 |

| b0008|8238_9191 | 954 | 1561 | 1636.268 | 554.028 |

| b0009|9306_9893 | 588 | 289 | 491.497 | 166.417 |

| b0010|C9928_10494 | 567 | 100 | 176.367 | 59.716 |

| b0011|C10643_11356 | 714 | 13 | 18.207 | 6.165 |

| b0013|C11382_11786 | 405 | 2 | 4.938 | 1.672 |

| b0014|12163_14079 | 1917 | 6863 | 3580.073 | 1212.186 |

| b0015|14168_15298 | 1131 | 1671 | 1477.454 | 500.255 |

| … | … | … | … | … |

One may ask how quality scores are treated when reads with identical sequences are grouped into the form of SeqID_CopyNumber format. Let me first highlight two observations. First, different reads with the same sequence have similar quality scores. For example, sequence “TGTTATCACGGGAGACACACGGCGGGTGCTAACGTCCGTCGTGAAGAGGG” occur many times in file SRR1526586.sra. I took the first six reads with this 50-nt sequence, and computed Pearson correlation among the associated quality scores (each read is associated with a vector of 50 quality scores). The correlation coefficients are all high and positive (Table 3). The same for sequences that occur just twice. Second, quality score itself is a statistical estimate. For these reasons, when reads with the same sequence are combined into the SeqID_CopyNumber format in Fastq+ file, the quality scores for this combined sequence are simply average quality scores. For a sequence of length L that occurred twice in the transcriptomic data, the sequence ID will be SeqID_2, and quality scores will simply be (Q1i + Q2i)/2, where i = 1, 2, …, L, and Q1 and Q2 are quality scores from the two reads of the same sequence.

Table 3. Correlation among quality scores from first six reads (Q1–Q6) of the same sequence of 50 nt (TGTTATCACGGGAGACACACGGCGGGTGCTAACGTCCGTCGTGAAGAGGG).

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q2 | 0.804889 | ||||

| Q3 | 0.662242 | 0.873874 | |||

| Q4 | 0.71594 | 0.938951 | 0.918316 | ||

| Q5 | 0.784977 | 0.968069 | 0.864678 | 0.945969 | |

| Q6 | 0.634808 | 0.850372 | 0.926804 | 0.931704 | 0.866401 |

Each read is associated with a vector of 50 quality scores (one for each nucleotide).

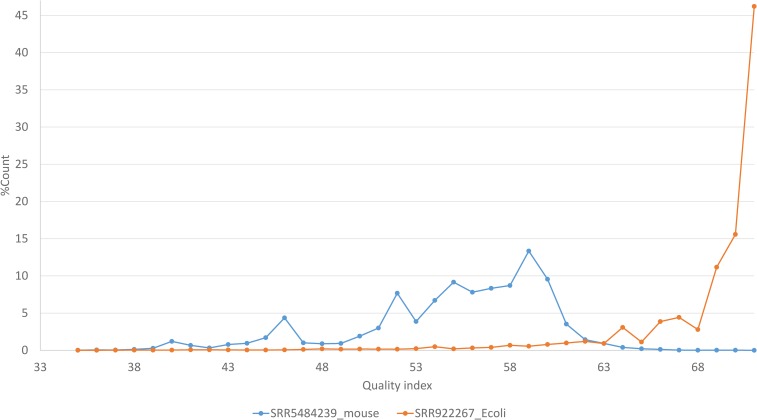

Size-reduction differs dramatically with read quality (Figure 2). For high-quality data, e.g., SRR922267 (Figure 2, where an overwhelming majority of bases are at the high-quality end), ARSDA can shrink file size to ∼0.05 of the original. However, for poor-quality data, e.g., SRR5484239 (Figure 2), ARSDA can shrink file size only to 0.64 of the original. The reason is that, with high-quality data, reads from the same segment of the transcript are identical, as one would expect, but, with low-quality data, reads from the same segment of the transcript have “mutated” during the amplification and sequencing step, and are often no longer identical. For SRR922267, the most redundant sequence has 2,341,386 identical copies out of 14,872,404 forward reads. In contrast, the most redundant sequence in SRR5484239 has only 1540 identical copies out of 10,702,871 reads. This implies that the paired-end reads, especially long ones, will likely have low size-reduction efficiency because reverse read quality is typically much worse than forward read quality. Size-reduction with the ARSDA approach works best with high-quality reads. Base-calling quality typically decreases rapidly with read length (Figure 1C). Trimming off the low-quality 3′ end of the reads typically leads to dramatically increased size-reduction efficiency.

Figure 2.

Contrasting read quality between two transcriptomic data files (SRR5484239.sra from M. musculus and SRR922267.sra from E. coli. It does not imply that E. coli data are always better than mouse data as there are also poor-quality E. coli data and high-quality mouse data.

One of the frequently used sequence-compression scheme is to use a reference genome so that each read can be represented by a starting and an ending number on the genome (Benoit et al. 2015; Kingsford and Patro 2015; Zhu et al. 2015a). This approach has two problems. First, many reads do not map exactly to the genomic sequence because of either somatic mutations or sequencing errors, so representing a read by the starting and ending numbers leads to loss of information. Second, RNA-editing and processing can be so extensive that it becomes impossible to map a transcriptomic read to the genome (Abraham et al. 1988; Lamond 1988; Alatortsev et al. 2008; Li et al. 2009; Simpson et al. 2016). Furthermore, there are still many scientifically interesting species that do not have a good genomic sequence available. One could add additional annotation and indexing for sequence variants resulting from RNA-editing and “mutants” resulting from amplification and sequencing to avoid information loss, but such additional steps reduces the efficiency of compression as well as increases an extra layer of complexity for downstream data analysis.

Software tools for compressing HTS files are often benchmarked against general-purpose GZIP tools (Numanagic et al. 2016). Among nonreference compression tools for FASTQ files, LFQC (Nicolae et al. 2015) was benchmarked to be the most efficient (Numanagic et al. 2016), partly because LFQC uses several compression programs separately for sequence IDs, sequences, and quality scores. I compared file size reduction from FASTQ+ format against compression results from GZIP and LFQC (Table 4). Because FASTQ+ files are simple text files that can be further compressed by GZIP and LFQC, Table 4 also include compression output of GZIP+FASTQ+ and LFQC+FASTQ+. The results (Table 4) confirms the previous finding (Numanagic et al. 2016) that LFQC is much more efficient than GZIP. They also show FASTQ+ to offer a substantial further reduction of file sizes. For SRR1536586, file size reduction efficiency is comparable between LFQC and FASTQ+ (Table 4). However, further compression with GZIP+FASTQ+ and LFQC+FASTQ+ both leads to much reduced file size than using GZIP or LFQC alone (Table 4), the same being true for the paired-end file SRR922270 (Table 4). Furthermore, FASTQ+ has one additional advantage in that it dramatically reduces computation time in downstream data analysis. Take SRR1536586 for example, FASTQ+ would reduce computation time for read-matching (which is the most time-consuming part of any transcriptomic data analysis) to a fraction of roughly 0.075 (≈119,596,093/1,604,183,348).

Table 4. Comparison of different compression methods from the original single-read file (SRR1536586) and paired-end read file (SRR922270) in FASTQ format.

| File Size (in Bytes) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Methods | SRR1536586 | SRR922270_1 | SRR922270_2 |

| FASTQ | 1,604,183,348 | 2,647,494,360 | 2,647,494,360 |

| GZIP | 299,347,123 | 441,010,173 | 466,626,719 |

| LFQC | 101,191,680 | 159,732,224 | 174,810,624 |

| FASTQ+a | 119,596,093 | 493,950,425 | 493,950,425 |

| GZIP+FASTQ+ | 35,078,888 | 130,605,692 | 130,546,296 |

| LFQC+FASTQ+ | 16,506,880 | 61,696,000 | 62,689,280 |

SRR1536586 and SRR922270 are SRA file IDs in NCBI SRA database.

After converting FASTAQ+ format, the quality score for an entry such as SeqID_200 is the mean for the 200 reads and not for individual sequences.

Assigning sequence reads to paralogous genes

One of the most fundamental objectives of RNA-Seq analysis is to generate an index of gene expression (FPKM: matched fragment/reads per kilobases of transcript per million mapped reads) that can be directly compared among different genes and among different experiments with different total number of matched reads (Mortazavi et al. 2008). The main difficulty in quantifying gene expression arises with sequence reads matching multiple paralogous genes (Trapnell et al. 2013; Rogozin et al. 2014). This problem, which has plagued microarray data analysis, is now plaguing RNA-Seq analysis. Most publications of commonly used RNA-Seq analysis methods (Langmead et al. 2009, 2010; Trapnell et al. 2009, 2012; Roberts et al. 2011, 2013; Langmead and Salzberg 2012; Dobin et al. 2013; Deng et al. 2014) often avoided mentioning read allocation to paralogous genes. The software tools associated with these publications share two simple options for handling matches to paralogous genes. The first is to use only uniquely matched reads, i.e., reads that match to multiple genes are simply ignored. The second is to assign such reads equally among matched genes. These options are obviously unsatisfactory. Here, I describe a new approach which should substantially improve the accuracy of HTS data analysis such as gene expression characterization.

Allocating sequence reads to paralogous genes in a two-member gene family

We need a few definitions to explain the allocation. Let L1 and L2 be the sequence length of the two paralogous genes. Let NU.1 and NU.2 be the number of reads that can be uniquely assigned to paralogous gene 1 or 2, respectively (i.e., the reads that matches one gene better than the other). Now for those reads that match the two genes equally well, the proportion of the reads contributed by paralogous gene 1 may be simply estimated as

| (1) |

Now, for any read that matches the two paralogous genes equally well, we will assign P1 to paralogous gene 1, and (1−P1) to paralogous gene 2. In the extreme case when paralogous genes are all identical, then NU.1 = NU.2 = 0, and we will assign 1/2 of these equally matched read to genes 1 and 2. We should modify Equation (1) to make it more generally applicable as follows

| (2) |

where 0.01 in the numerator and 0.02 in the denominator are pseudocounts. The treatment in Equation (2) implies that, when NU.1 = NU.2 = 0(e.g., when two paralogous genes are perfectly identical), then a read matching equally well to these paralogous genes will be equally divided among the two paralogues.

One problem with this treatment is its assumption of L1 = L2. If paralogous gene 1 is much longer than the other, then NU.1 is expected to be larger than NU.2, everything else being equal. One may standardize NU.1 and NU.2 to number of unique matches per 1000 nt, designated by SNU.i = 1000NU.i/Li (where i = 1 or 2) and replace NU.i in Equation (2) by SNU.i as follows (Mortazavi et al. 2008):

| (3) |

Allocating sequence reads in gene family with more than two members

One might, mistakenly, think that it is quite simple to extend Equation (3) for a gene family of two members to a gene family with F members by writing

| (4) |

This does not work. For example, if we have three paralogous genes designated A, B, and C, respectively. Suppose that the gene duplication that gave rise to B and C occurred very recently so that B and C are identical, but A and the ancestor of B and C have diverged for a long time. In this case, NU.B = NU.C = 0 because a read matching B will always match C equally well, but NU.A may be >0. This will result in unfair allocation of many transcripts from B and C to A according to Equation (4). I outline the approach below for dealing with gene families with more than two members.

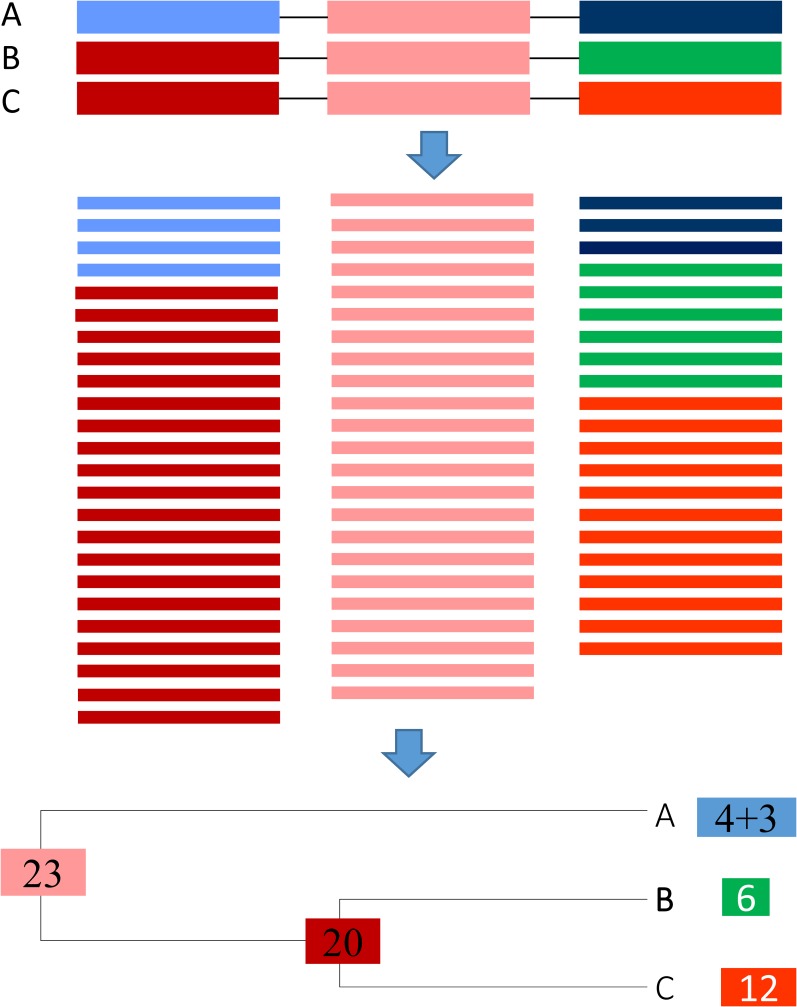

With three or more paralogous genes, one may benefit from a phylogenetic tree for proper allocation of sequence reads. I illustrate the simplest case with a gene family with three paralogous genes A, B, and C, idealized into three segments in Figure 3. The three genes shared one identical middle segment with 23 matched reads (that necessarily match equally well to all three paralogues). Genes B and C share an identical first segment to which 20 reads matched. Gene A has its first segment different from that of B and C, and got four matched reads. The three genes also have a diverged third segment where A matched three reads, B matched six and C matched 12. Our task is then to allocate the 23 reads shared by all three, and 20 reads shared by B and C to the three paralogues.

Figure 3.

Allocation of shared reads in a gene family with three paralogous genes A, B, and C with three idealized segments with a conserved identical middle segment, strongly homologous first segment that is identical in B and C, and a diverged third segment. Reads and the gene segment they match to are of the same color.

One could apply maximum likelihood or least-squares method for the estimation, but ARSDA uses a simple counting approach by applying the following

| (5) |

Thus, we allocate the 23 reads (that matched three genes equally) to paralogous genes A, B, and C according to PA, PB, and PC, respectively. For the 20 reads that matched B and C equally well, we allocate 20*6/(6 + 12) to B and 20*12/(6 + 12) to C. This gives the estimated number of matches to each gene as

| (6) |

These numbers are then normalized to give FPKM (Mortazavi et al. 2008). The current version of ARSDA assume that gene families with more than two members to have roughly the same sequence lengths. This is generally fine with prokaryotes but may become problematic with eukaryotes.

In practice, one can obtain the same results without actually undertaking the extremely slow process of building trees for paralogous genes. One first goes through reads shared by two paralogous genes (e.g., the 20 reads shared by genes B and C in Figure 3) and allocate the reads according to PB = 6/(6 + 12) = 1/3 and PC = 12/(6 + 12) = 2/3. Now genes B and C will have 12.66667 (= 6 + 20*PB) and 25.33333 (= 12 + 20*PC) assigned reads, i.e., NU.B = 12.66667 and NU.C = 25.33333. Once we have done with reads shared by two paralogous genes, we go through reads shared by three paralogous genes, e.g., the 23 reads shared by genes A, B, and C in Figure 3. With NU.A = 7, NU.B = 12.66667, NU.C = 25.333333, and N = NU.A + NU.B + NU.C = 45, so we have

| (7) |

| (8) |

which are the same as shown in Equation (6). This progressive process continues until we have allocated reads shared by the largest number of paralogous genes. The gene expression output in File S1 was obtained in this way.

There are alternative approaches for read allocation among paralogous genes. ARSDA also has an alternative allocation scheme based on BitScores and e-values. For example, when a read exhibits strong homology to N paralogous genes, but with different e-values or BitScores, I will not assign the read to the paralogous gene with the smallest e-value (or largest BitScore). Instead, all N paralogous genes will get a share of the read according to sequence similarity reflected in e-value and BitScore. The simplest scheme based on BitScore is to allocate such a read to paralogous gene i according to

| (9) |

which would give a paralogous gene with high BitScore a higher share. An alternative based on e-value is

| (10) |

where E is e-value and K is a scaling factor to ensure that ∑pi = 1. Equation (10) allocates shared reads more to the paralogous gene with a small e-value than those with large e-value. In practice, Equation (9) is often close to equal allocation, whereas Equation (10) results in more biased allocation favoring the best-match paralogous genes.

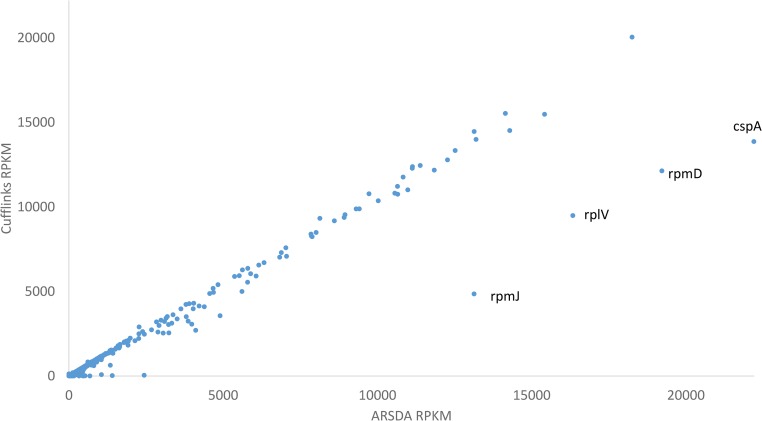

Contrast Between ARSDA and Cufflinks in Characterizing Gene Expression

The most frequently used software for gene expression is Cufflinks (Trapnell et al. 2012), which is why I am contrasting ARSDA against it. I will use the transcriptomic data for an E. coli wild type (Pobre and Arraiano 2015), archived in NCBI’s SRA database as SRR1536586.sra. The Cufflinks-quantified gene expression for this file is in file GSM1465035_WT.txt.gz from NCBI Geo DataSets GSM1465035. Gene expression from ARSDA and Cufflinks in mostly concordant (Figure 4), but four points (labeled in Figure 4) stand out as outliers (although many more discordant points will be revealed by a log-log plot). Such dramatic differences demand an explanation. Take rpmJ for example. Either ARSDA severely overestimated, or Cufflinks severely underestimated, the gene expression (Figure 4). I originally expected the discrepancy to be due to different allocation of paralogous genes. The expectation is only partially true.

Figure 4.

Contrast in gene expression (RPKM) between ARSDA and Cufflinks output for the same transcriptomic data in file SRR1536586.sra for E. coli wild type.

There are 6426 reads can be mapped unambiguously to rpmJ (which is in fact a single-copy ribosomal protein gene). Although there are rpmA, rpmB, …, rpmJ genes in E. coli, they are not paralogous. One particular read “AGTGCCGAGCCGAAGCATAAACAGCGCCAAGGCTGATTTTTTCGCATATT” occurs 2684 times in SRR1536586.sra. It matches perfectly to the 36 nt at the 3′ end of rpmJ and 14 nt immediately downstream. However, Cufflinks output reported a count of only 2114 reads for rmpJ instead of 6426 (and consequently the much reduced RPKM in Figure 4). I originally suspected that rpmJ may be in an operon with an immediate downstream gene so that some read overlapping rpmJ and the downstream gene would be divided between the two. However, the downstream gene, which is rpsM, is 146 nt away. It is difficult to reconcile 6426 nonambiguous read matches to Cufflinks’ 2114. Similarly, rpmD and rplV (Figure 4) has 14,468 and 22,747 unambiguous read matches, respectively, but the corresponding counts in Cufflinks output are only 8108 and 11,801, respectively. Note that rpmD and rplV are also single-copy genes with no ambiguous read matches. E. coli genes rpmA–rpmJ are not paralogous, neither are rplA–rplY.

The last outlying gene (cpsA in Figure 4) does involve a paralogous gene family (Figure 5). cspA has 19,776 unambiguous read matches, but Cufflinks output has only 10,957, which resulted in a much lower RPKM than that from ARSDA (Figure 4). Also puzzling are the counts involving cspF and cspH. There are 264 unambiguous read matches to cspF and 58 to cspH. There are also 55 reads that match well to both cspF and cspH, with 27 of them matching cspF better than cspH, and 28 matching cspH better than cspF. So we may assign (264 + 27) reads to cspF and (58 + 28) reads to cspH, with relative proportions of 0.7719 and 0.2281 for cspF and cspH, respectively. Twelve reads match cspF and cspH equally well (the same e-value and the same BitScore), so we assign them proportionally to the two genes, i.e., 12*0.7719 to cspF and 12*0.2281 to cspH. The final counts for cspF and cspH are 300.2626 and 88.7374, respectively. However, Cufflinks output shows counts of 2 and 63 for cspF and cspH, respectively. The discrepancy is particularly striking given that gene expression from ARSDA and Cufflinks are mostly concordant (Figure 4). The alternative allocation to paralogous genes as specified in Equations (9) and (10) does not help reconcile the discrepancy. I hope that these numbers will prompt authors of Cufflinks to be more explicit about how they treats counts.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic relationship among paralogous genes cspA to cspI in E. coli, based on coding sequences, with bootstrap values next to internal nodes. Sequences were aligned by MAFFT (Katoh and Toh 2008) with accurate L_INS-i option and a maximum of 16 iterations. Coding sequences were first translated in amino acid sequences, which are aligned with BLOSUM62 matrix. Nucleotide sequences were then aligned against aligned amino acid sequences. Phylogenetic analysis was done with PhyML (Guindon et al. 2010). All these analyses were automated in DAMBE (Xia 2013, 2017).

Software and data availability

ARSDA is freely available at http://dambe.bio.uottawa.ca/ARSDA/ARSDA.aspx, together with a QuickStart.PDF file showing HTS file conversion from FASTA/FASTQ file to FASTA+ format, three types of HTS data quality visualization tools, and downstream characterization of gene expression. It is a Windows program, but can run on any computer with .NET framework installed (e.g., Macintosh and Linux with MONO installed and activated). The BLAST databases derived from HTS reads for several model species, in which sequence IDs are in the format of SeqID_CopyNumber, are deposited at coevol.rdc.uottawa.ca. One can use these BLAST databases with ARSDA to characterize gene expression or other analysis. The QuickStart.PDF file available at the same site details the use of ARSDA, either alone or in conjunction with the free DAMBE software (Xia 2013, 2017). The source code is available as a zipped supplemental file ARSDA.Src.zip in https://github.com/xuhuaxia/ARSDA.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental material is available online at www.g3journal.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/g3.117.300271/-/DC1.

Acknowledgments

Nabil Benabbou of Center for Advanced Computing of Queen’s University helped me with testing compression software tools on the center’s servers. ARSDA was demonstrated in two workshops, one organized by J. Lu of Peking University, and another by E. Pranckeviciene of University of Vilnius. I thank participants, as well as J. Silke, J. Wang, Y. Wei, and C. Vlasschaert, for their feedback. Two anonymous reviewers offered outstanding feedback leading to substantial improvement of the manuscript. This study is funded by the Discovery Grant from Natural Science and Engineering Research Council (RGPIN/261252) of Canada.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: C. Myers

Literature Cited

- Abraham J. M., Feagin J. E., Stuart K., 1988. Characterization of cytochrome c oxidase III transcripts that are edited only in the 3′ region. Cell 55: 267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alatortsev V. S., Cruz-Reyes J., Zhelonkina A. G., Sollner-Webb B., 2008. Trypanosoma brucei RNA editing: coupled cycles of U deletion reveal processive activity of the editing complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28: 2437–2445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, S., 2017 FastQC, Babraham Bioinformatics. Available at: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc.

- Arava Y., Wang Y., Storey J. D., Liu C. L., Brown P. O., et al. , 2003. Genome-wide analysis of mRNA translation profiles in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 3889–3894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awan A. R., Manfredo A., Pleiss J. A., 2013. Lariat sequencing in a unicellular yeast identifies regulated alternative splicing of exons that are evolutionarily conserved with humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110: 12762–12767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit G., Lemaitre C., Lavenier D., Drezen E., Dayris T., et al. , 2015. Reference-free compression of high throughput sequencing data with a probabilistic de Bruijn graph. BMC Bioinformatics 16: 288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai M., Thompson R. C., Maher C., Contreras-Galindo R., Kaplan M. H., et al. , 2010. NGSQC: cross-platform quality analysis pipeline for deep sequencing data. BMC Genomics 11(Suppl. 4): S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Q., Ramskold D., Reinius B., Sandberg R., 2014. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals dynamic, random monoallelic gene expression in mammalian cells. Science 343: 193–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A., Davis C. A., Schlesinger F., Drenkow J., Zaleski C., et al. , 2013. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29: 15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GB Editorial Team , 2011. Closure of the NCBI SRA and implications for the long-term future of genomics data storage. Genome Biol. 12: 402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S., Dufayard J. F., Lefort V., Anisimova M., Hordijk W., et al. , 2010. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 59: 307–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingolia N. T., Ghaemmaghami S., Newman J. R. S., Weissman J. S., 2009. Genome-wide analysis in vivo of translation with nucleotide resolution using ribosome profiling. Science 324: 218–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingolia N. T., Lareau L. F., Weissman J. S., 2011. Ribosome profiling of mouse embryonic stem cells reveals the complexity and dynamics of mammalian proteomes. Cell 147: 789–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janin L., Schulz-Trieglaff O., Cox A. J., 2014. BEETL-fastq: a searchable compressed archive for DNA reads. Bioinformatics 30: 2796–2801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Toh H., 2008. Recent developments in the MAFFT multiple sequence alignment program. Brief. Bioinform. 9: 286–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima T., Douglass S., Gabunilas J., Pellegrini M., Chanfreau G. F., 2014. Widespread use of non-productive alternative splice sites in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS Genet. 10: e1004249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsford C., Patro R., 2015. Reference-based compression of short-read sequences using path encoding. Bioinformatics 31: 1920–1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama Y., Shumway M., Leinonen R., 2012. The sequence read archive: explosive growth of sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 40: D54–D56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamond A. I., 1988. RNA editing and the mysterious undercover genes of trypanosomatid mitochondria. Trends Biochem. Sci. 13: 283–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Salzberg S. L., 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9: 357–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Trapnell C., Pop M., Salzberg S. L., 2009. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 10: R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Hansen K. D., Leek J. T., 2010. Cloud-scale RNA-sequencing differential expression analysis with Myrna. Genome Biol. 11: R83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinonen R., Sugawara H., Shumway M., 2011. The sequence read archive. Nucleic Acids Res. 39: D19–D21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Ge P., Hui W. H., Atanasov I., Rogers K., et al. , 2009. Structure of the core editing complex (L-complex) involved in uridine insertion/deletion RNA editing in trypanosomatid mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106: 12306–12310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Guo H., Brudno M., Wang Y., 2016. deBGA: read alignment with de Bruijn graph-based seed and extension. Bioinformatics 32: 3224–3232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKay V. L., Li X., Flory M. R., Turcott E., Law G. L., et al. , 2004. Gene expression analyzed by high-resolution state array analysis and quantitative proteomics: response of yeast to mating pheromone. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 3: 478–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi A., Williams B. A., McCue K., Schaeffer L., Wold B., 2008. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat. Methods 5: 621–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolae M., Pathak S., Rajasekaran S., 2015. LFQC: a lossless compression algorithm for FASTQ files. Bioinformatics 31: 3276–3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numanagic I., Bonfield J. K., Hach F., Voges J., Ostermann J., et al. , 2016. Comparison of high-throughput sequencing data compression tools. Nat. Methods 13: 1005–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleiss J. A., Whitworth G. B., Bergkessel M., Guthrie C., 2007. Rapid, transcript-specific changes in splicing in response to environmental stress. Mol. Cell 27: 928–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pobre V., Arraiano C. M., 2015. Next generation sequencing analysis reveals that the ribonucleases RNase II, RNase R and PNPase affect bacterial motility and biofilm formation in E. coli. BMC Genomics 16: 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A., Trapnell C., Donaghey J., Rinn J. L., Pachter L., 2011. Improving RNA-Seq expression estimates by correcting for fragment bias. Genome Biol. 12: R22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A., Schaeffer L., Pachter L., 2013. Updating RNA-Seq analyses after re-annotation. Bioinformatics 29: 1631–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers M. F., Thomas J., Reddy A. S., Ben-Hur A., 2012. SpliceGrapher: detecting patterns of alternative splicing from RNA-Seq data in the context of gene models and EST data. Genome Biol. 13: R4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogozin I. B., Managadze D., Shabalina S. A., Koonin E. V., 2014. Gene family level comparative analysis of gene expression in mammals validates the ortholog conjecture. Genome Biol. Evol. 6: 754–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson R. M., Bruno A. E., Bard J. E., Buck M. J., Read L. K., 2016. High-throughput sequencing of partially edited trypanosome mRNAs reveals barriers to editing progression and evidence for alternative editing. RNA 22: 677–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepankiw N., Raghavan M., Fogarty E. A., Grimson A., Pleiss J. A., 2015. Widespread alternative and aberrant splicing revealed by lariat sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 43: 8488–8501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C., Pachter L., Salzberg S. L., 2009. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics 25: 1105–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C., Roberts A., Goff L., Pertea G., Kim D., et al. , 2012. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc. 7: 562–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C., Hendrickson D. G., Sauvageau M., Goff L., Rinn J. L., et al. , 2013. Differential analysis of gene regulation at transcript resolution with RNA-seq. Nat. Biotechnol. 31: 46–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlasschaert C., Xia X., Gray D. A., 2016. Selection preserves Ubiquitin Specific Protease 4 alternative exon skipping in therian mammals. Sci. Rep. 6: 20039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X., 2013. DAMBE5: a comprehensive software package for data analysis in molecular biology and evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30: 1720–1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X., 2017. DAMBE6: new tools for microbial genomics, phylogenetics and molecular evolution. J. Hered. 108: 431–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X., MacKay V., Yao X., Wu J., Miura F., et al. , 2011. Translation initiation: a regulatory role for poly(A) tracts in front of the AUG codon in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 189: 469–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z., Li L., Zhang Y., Yang Y., Yang X., 2015a CompMap: a reference-based compression program to speed up read mapping to related reference sequences. Bioinformatics 31: 426–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z., Zhang Y., Ji Z., He S., Yang X., 2015b High-throughput DNA sequence data compression. Brief. Bioinform. 16: 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.