Abstract

Despite advanced efforts in early diagnosis, aggressive surgical treatment, and use of targeted chemotherapies, the prognosis for many cancers is still dismal. This emphasizes the necessity to develop new strategies for understanding tumor growth and metastasis. Here we use a systems approach that combines mathematical modeling and numerical simulation to develop a predictive computational model for prostate cancer and its subversion of the bone microenvironment. This model simulates metastatic prostate cancer evolution, progressing from normal bone and hormone levels to quantifiable diseased states. The simulations clearly demonstrate phenomena similar to those found clinically in prostate cancer patients. In addition, the major prediction of this model is the existence of low and high osteogenic states that are markedly different from one another. The existence and potential realization of these steady states appear to be mediated by the Wnt signaling pathway and by the effects of PSA on TGF-β, which encourages the bone microenvironment to evolve. The model is used to explore several potential therapeutic strategies, with some potential drug targets showing more promise than others: in particular, completely blocking Wnt and greatly increasing DKK-1 had significant positive effects, while blocking RANKL did not improve the outcome.

Keywords: Mathematical model, Prostate cancer, Bone metastasis

1 Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common malignancy and a leading cause of cancer-related death in American men [44]. As PCa progresses, it has a predisposition to metastasize to bone as opposed to other sites resulting approximately 90% of men with advanced PCa having bone micrometastases [8]. The difference between survival rates of localized prostate cancer and cancer that has metastasized throughout the body is marked: the former has a nearly 100% five-year survival rate, while the latter is associated with survival rates of 28% [43]. PCa bone metastases are somewhat unique compared to metastases from most other cancers. Specifically, most cancers induce osteolytic (i.e., bone resorptive) lesions, whereas PCa induces osteoblastic (bone productive) lesions [34]. The mechanisms that account for bone being a favored site for PCa growth and the ultimate induction of osteoblastic lesions are not well defined. Understanding these mechanisms could lead to the identification of new therapeutic targets. Modeling metastasis and attempting to interfere with the pathology in silico can be vital to understanding the disease pathology and has the potential to guide drug development efforts.

Prostate cancer metastases in the bone microenvironment overwrite the natural, tightly controlled processes of bone remodeling to better suit the growth of the tumor. Primarily, two specialized cell types orchestrate the formation and degradation of bone: osteoblasts, which produce bone matrix and aid its mineralization [29], and osteoclasts, a unique cell type that dissolves bone mineral [47]. Osteoblasts can be induced to express receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL) in response to bone resorption-stimulating factors such as parathyroid hormone (PTH) [13]. Osteoblasts also express a negative regulator of bone resorption, osteoprotegerin (OPG), which inhibits the interaction between RANK and RANKL by acting as a decoy receptor of RANKL [45]. Studies of diseases associated with defects in bone formation have demonstrated the crucial importance of the Wnt signaling pathway [18] in promoting bone formation and inhibiting bone resorption. Canonical Wnt signaling promotes differentiation of uncommitted osteoblast precursors (OBu) into active osteoblasts (OBa), which in turn increases bone formation [18, 30]. Wnt signaling also induces the up-regulation of OPG expression and down-regulation of RANKL expression in osteoblasts, resulting in the inhibition of bone resorption [30]. Mesenchymal cells secrete Dickkopf-related protein (DKK-1), a Wnt signaling pathway inhibitor that antagonizes canonical Wnt signaling by blocking its interaction with low-density lipoprotein receptor-related proteins [24].

Calcium, as a nutrient, is most commonly associated with the formation and metabolism of bone. Osteoblasts uptake blood calcium (Ca2+) in order to produce bone [4]. However, as Ca2+ is reduced in the bloodstream, the parathyroid glands secrete parathyroid hormone (PTH) [36]. Osteoblast precursors are stimulated to produce RANKL by the PTH, which also inhibits osteoblasts from producing OPG. RANKL encourages osteoclast precursors (OCp) to differentiate into active osteoclasts (OCa), which resorb bone and release both Ca2+ and TGF-β in its latent form, LTGF-β [16]. Increasing calcium levels signal the parathyoids to stop producing PTH [7]. In time, LTGF-β is transformed into its active form, which encourages osteoclast apoptosis as well as the differentiation of uncommitted osteoblast precursors into osteoblast precursor cells. TGF-β also inhibits the differentiation of osteoblast precursors (OBp) into active osteoblasts [17]. This way, equilibrium is maintained by the body in order to preserve calcium and bone homeostasis.

When prostate cancer metastasizes to bone, the natural equilibrium is entirely disrupted. The main reason is that prostate cancer cells produce Wnt in far larger quantities than usually present in the body. This can be somewhat mitigated by the fact that prostate cancer cells that have not fully acclimated (PCe) to the bone microenvironment also produce DKK-1 [23]. All prostate cancer cells produce modified parathyroid hormone (PTHrP) [3]; however, prostate cancer cells that have adapted to the bone microenvironment (PCl) also produce prostate specific antigen (PSA), which inhibits PTHrP [12]. Overexpression of Wnt results in increases in OBa and their predecessors, which rapidly produce RANKL [6, 54]. This causes bone formation while simultaneously stimulating OCa production which leads to rapid bone resorption. This results in large bone turnover, releasing LTGF-β [33]. When LTGF-β is activated, it encourages the proliferation of PCl [21]. This, in turn, increases the concentration ofWnt, creating a bidirectional crosstalk in which the growing tumor remodels bone to sustain additional cancer growth; this is the so-called “vicious cycle” of prostate cancer metastasis [11].

2 Model Development

In order to quantify the influence of critical pathways that mediate crosstalk between PCa and the bone microenvironment, we will track temporal changes of the following cell and tissue types listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Cell Types and Initial Conditions

| Cell Type | Description | Initial Values | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| OBp | Osteoblast precursor cells | 1.2005084 × 109 | # of cells |

| OBa | Active Osteoblasts | 1.0001628 × 109 | # of cells |

| OCa | Active Osteoclasts | 1.674764 × 108 | # of cells |

| BONEt | Normalized Bone Volume | 100 | % |

| PCe | Early PCa cells | 0 | # of cells |

| PCl | Late PCa cells | 0 | # of cells |

Additionally, we will model the following important signaling proteins and chemokines that mediate bone remodeling and PCa growth listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Bone Regulatory Proteins

| Signaling Molecule | Description | Units |

|---|---|---|

| RANKL | Receptor activator of NF-κB ligand | pM |

| OPG | Osteoprotegerin | pM |

| Ca2+ | Bloodstream calcium | M |

| PTHrP | Parathyroid hormone-related protein | pM |

| TGFβ | Active TGF-β | pM |

| LTGFβ | Latent TGF-β | pM |

| WNT | Wnt signaling protein | pM |

| DKK1 | Dickkopf-related protein | pM |

| PSA | Prostate Specific Antigen | pM |

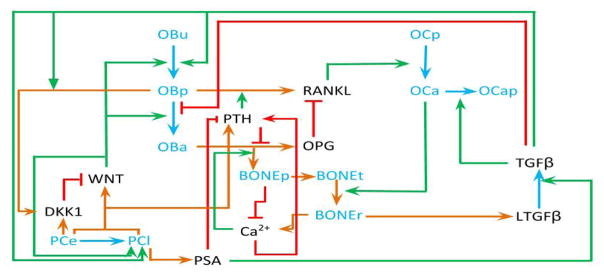

A schematic diagram of the model is given in Figure 1, and the model equations and their explanations are provided in the subsections below.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram illustrating the proposed interactions and feedback loops for the mathematical model. PCe = PCa early and PCl = PCa late. OBu = undifferentatiated bone cells, OBp and OCp = osteoblast and osteoclast precursors; respectively. OBa and OCa = active osteoblasts and osteoclasts; respectively. LTGFβ = latent TGF-β, BONEt = total bone, BONEp = bone production, and BONEr = bone resorption.

2.1 Bone Cell Remodeling Equations

Our mathematical model of the bone microenvironment is based on that of [49]; however, we have posed several modifications. In particular, one new feature of our model is that we incorporate not only the effects of TGF-β on bone cell differentiation, but also the effects of Wnt and DKK-1. TGF-β is an important regulator of osteoblast and osteoclast activity during bone growth and remodeling [20]. There are also molecular links between Wnt signaling and bone development and remodeling [30]. Wnt not only promotes OBu differentiation into OBp as TGF-β does, but also encourages OBp to differentiate into OBa, in direct contrast to TGF-β [18]. DKK1 regulates Wnt signaling and inhibits osteoblastogenesis [24, 30]. Equations 1–5 below describe the temporal changes in the evolution of the bone cells and the total bone volume, as mediated by this signaling network.

2.1.1 Osteoblast Precursor Cells (OBp)

| (1) |

| (2) |

In equation (1), we assume that bone marrow stem cells (BMSCs, or in terms of the model, OBu for uncommitted cells) are in constant supply, and that, on average, every OBu mitotic event produces one OBp. This assumption is based on the fact that the osteoblastic lineage derives from an abundant pool of stem cells and is in line with other mathematical models of bone formation [38, 49]. The first term ensures that differentiation of OBu into OBp relies on sources of OBu, TGF-β, and Wnt. Specifically, active TGF-β and Wnt stimulate OBu to differentiate into osteoblast precursor cells (OBp). The generation of osteoblast precursors is simultaneously controlled by two ligands, therefore we use the functional form derived in [49] in equation (2) to describe these enhanced effects. We choose to subtract the product of the activation expressions, as we assume that there are no synergistic interactions between Wnt and TGF-β in activating OBu differentiation. The second term describes the differentiation of OBp into OBa. Here, active TGF-β inhibits osteoblast precursor cells from differentiating into active osteoblasts (OBa), while Wnt simulates this differentiation.

The parameters δOBu, δOBp1, and δOBp2 are the differentiation rates of bone marrow stem cells and osteoblast precursors; respectively. The parameters KTGFβa1, KTGFβr1, KWNTa1, and KWNTa2 represent activation (or repression) constants for TGF-β and Wnt respectively, which are the ligand concentrations that induce a half-maximal cellular response.

2.1.2 Active Osteoblasts (OBa)

| (3) |

Equation (3), for temporal changes in activated osteoblasts, describes the only source of active osteoblasts (OBa) as the differentiation of OBp into OBa, and so the first term is identically equal to the additive inverse of the differentiation term in equation (1). The apoptotic rate of osteoblasts, αOBa, is linearly proportional to the amount of osteoblasts in the system, and is not altered by the hormonal environment.

2.1.3 Active Osteoclasts (OCa)

| (4) |

In equation (4), we consider the osteoclast precursor (OCp) population to be constant in the system, as an analogue to OBu, and set differentiation to have a maximum rate δOCp of osteoclasts (OCa) generated per day. We modify this maximum with a dependency on RANKL, which signals differentiation of OCp to OCa, where KRANKLa1 is the concentration of RANKL that induces a half-maximal response. We also take the apoptosis of OCa to be linearly dependent on the amount of OCa in the system. However, the proportionality is presumed to vary, starting with a base rate αOCa1 and then increasing as TGF-β increases. Here, αOCa2 is the maximum TGF-β induced apoptosis rate and KTGFβa2 is the half-maximal concentration of TGF-β. This contrasts slightly with [49], as they assume that all osteoclast destruction is mediated by TGF-β, and we incorporate this additional term as a simplification of other factors that induce OCa apoptosis that we do not explicitly track, e.g. IL-6 [53].

2.1.4 Total Bone Volume (BONEt)

| (5) |

Bone volume (Equation (5)) is changed by only two factors: bone synthesis by osteoblasts and bone resorption by osteoclasts. Here, BONEt is considered to be the normalized volume of total bone material. The first term represents bone production by osteoblasts, which is usually assumed to be directly proportional to the amount of osteoblasts in the system [38, 49]. However, bone formation requires calcium, so we augment this term to depend on calcium concentration in low calcium conditions, while allowing bone synthesis to remain relatively independent of calcium levels otherwise. The second term denotes bone resorption by osteoclasts, which is simply considered to be directly proportional to the number of osteoclasts in the system. The parameters Kform and Kres are the relative bone resorption and formation rates respectively, and KCa2+ is the concentration of calcium at which bone formation rate is halved.

In summary, Equations (1) – (5) describe the ways in which uncommitted stem cells are induced by factors such as Wnt and TGF-β to commit to osteoblast precursor cells. These cells can be induced by Wnt to become active osteoblasts that secrete mineral (BONEp) and increase the total bone volume (BONEt). RANKL induces osteoclast precursors to become active osteoclasts that induce resorption (BONEr) of bone and decreases the total bone volume. Active TGF-β induces active osteoclasts to become apoptotic and promotes the differentiation of osteoclast precursors into active osteoclasts through enhancing RANKL production. In the next section we develop the model equation of the proteins and chemokines that regulate bone remodeling.

2.2 Bone Regulation Signaling Molecule Equations

Bone is a dynamic tissue that undergoes continual adaption. These tightly coordinated events require the synchronized activities of multiple cellular participants. Below we develop equations for several key molecular players that regulate the cell types involved.

2.2.1 Calcium (Ca2+)

| (6) |

The inclusion of blood calcium ions (Ca2+), as described in Equation (6), is a novel addition to the model. Calcium acts as a limiting resource for bone growth, without which the model can predict drastic inflation of bone. The parameter i represents absorption from dietary intake, while the second term describes calcium excretion. Here, SPTH and SCa2+ represent normal steady state levels of parathyroid hormone and calcium in the system. Dietary intake is considered roughly equal to urinary excretion under normal conditions, and even when the body is trying to recuperate calcium, excretion is still proportional to the uptake of calcium. This assumption is used for fundamental reasons: the body’s purpose in excreting calcium is retaining an isotonic molarity in the bloodstream [35]. Ergo, if intake increases, excretion must increase to compensate. A linear relationship is used because in adults without cancer, there is a constant isotonic maintenance of approximately the same calcium molarity in blood and no net bone growth; therefore, any intake must have an equal removal. Therefore, the excretion term simplifies to i when calcium is at steady state to keep with this assumption. As calcium decreases in the system, excretion slows to a trickle, which is only further aided by PTHrP, which is scaled by the steady state PTH value to retain appropriate units. The last term changes the calcium in the system based on the creation and resorption of bone. The conversion factor Q denotes how much calcium is released with one percent destruction of bone volume; it has units of , and it is derived from several different analyses of bone geometry and structure. The parameter Q can be taken to be a constant in this model only because bone volume remains relatively unchanged: the linearity of bone volume change to blood calcium variation breaks down as volume is significantly altered.

2.2.2 Latent Transforming Growth Factor Beta (LTGFβ)

| (7) |

The inclusion of latent TGF-β is another new feature of our model. TGF-β is produced by most tissues, including bone, as a complex that is biologically inert [5]. The release of active protein from this latent form is critical for TGF-β to initate effects on target cells [5]. Therefore, the inclusion of the latent complex and the mechanisms responsible for active release are important for understanding TGF-β actions. Consistent with the known physiology, in equation (7), latent TGF-β is released when bone is resorbed and it is constantly degraded at rate λLTGFβ. The parameter μ, in the first term, converts the amount of bone resorbed into the amount of LTGF-β released. In the third term we see that in the absence of PSA, latent TGF-β is activated at rate βLTGFβ1. In the presence of PSA, there is enhanced activation of latent TGF-β into active TGF-β at maximum rate βLTGFβ2. The parameter KPSAa1 is the half-saturation constant of the PSA-mediated response of latent TGF-β.

2.2.3 Active Transforming Growth Factor Beta (TGFβ)

| (8) |

In equation (8), latent TGF-β (inactive) is cleaved by PSA and other proteins to make active TGF-β, which is then constantly degraded at rate λTGFβ. We recognize that TGF-β is also produced by prostate cancer cells in the presence of PSA, but we assume this relative amount is small enough to be neglected in comparison to that released by bone resorption.

2.2.4 Total Parathyroid Hormone (PTH total)

| (9) |

| (10) |

PTH is not only an important endocrine regulator of calcium, it also differentially regulates expression of RANKL and OPG [25]. In this model, we track both PTH, which is naturally present in the bone, and PTHrP, which is produced by prostate cancer cells and is a key mediator for communication and interactions between prostate cancer and the bone microenvironment [32]. The steady state PTH and PTHrP equations (10) are derived based on [38] under the following assumptions: 1) binding reactions leading to upregulation and down-regulation of both PTH and PTHrP are much faster than the cell responses, and therefore the quasi-steady approximation is valid, 2) PTH is produced naturally in the bone at a constant rate, 3) natural degradation of both PTH and PTHrP is proportional to their respective concentrations, and 4) PTH and PTHrP binding to its receptors on osteoblast precursor cells and active osteoblasts is the same. To these general bone regulation assumptions we add the following PCa-specific assumptions for PTHrP: 1) PTHrP is only produced by PC and 2) PTHrP is degraded by PSA or in other words, the PTHrP degradation rate increases as PSA levels increase. Here, PC=PCe+PCl, representing the total amount of PCa cells in the bone. The parameters βPTH and βPTHrP are the production rates of PTH and PTHrP, respectively, and λPTH and λPTHrP1 are their natural degradation rates. The rate of PSA-dependent degradation of PTHrP is given by λPTHrP2. Adding equations (9) and (10), we get the total amount of PTH protein at steady state given in equation (11).

| (11) |

2.2.5 Osteoprotegerin (OPG)

| (12) |

The steady state OPG equation (12) is derived directly from [38]. Consistent with both experimental data and the mathematical model in [38], we assume that OPG is only expressed on OBa cells and OPG is downregulated by the PTH proteins. Recall, PTHtotal=PTH+PTHrP. The critically important difference here is that OPG is upregulated by PSA indirectly via PTHrP decrease. The parameter βOPG is the OBa-dependent production rate of OPG, OPGmax is the carrying capacity for OPG in the system, and λOPG is the constant degradation rate. The half-saturation constant for the effect of PTH proteins on OPG production is given by KPTHtotalr1. The function POPG,d(t) represents external dosing; it is included here for completeness, however, it will be set to zero in the simulations unless otherwise noted.

2.2.6 Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor Kappa-B Ligand (RANKL)

| (13) |

The steady state RANKL equation (13) is derived directly from [49], where its production is controlled by the total amount of PTH protein. RANKL binds to both OPG (at rate KA,OPG) and RANK (at rate KA,RANK). The parameter ρ is the maximum amount of RANKL that a given osteoblast precursor can produce, and R denotes the amount of RANK available on OCp cells. Again, the difference here is that production is also indirectly under the control of PSA through its role in PTHrP degradation. The parameters βRANKL and λRANKL are the OBp-dependent production rate of RANKL and RANKL degradation rate; respectively. The half-saturation constant for the effect of the PTH proteins on RANKL production is given by KPTHtotala1 and PRL,d(t) represents external dosing.

Equations (6) – (13) describe proteins and chemokines that regulate bone remodeling. Completely new features of our model include the incorporation of calcium as a key mediator of bone production, the consideration of the important role of latent TGF-β in producing the active form of the protein, and the inclusion of prostate cancer-derived PTHrP and its role in osteoblastic progression. In the next section we develop equations for prostate cancer subversion of the bone microenvironment.

2.3 Prostate Cancer Cell Equations (PCe)

The spread of cancer to bone has several complex steps. Our model begins after the processes of localized tissue invasion and vessel intravasation/extravasation into the bone. Once in the bone, prostate cancer cells must acclimate to the bone microenvironment and avoid attacks from the immune system. So, while adjusting to their new surroundings these cells undergo phenotypic changes that lead to the new, bone-conditioned tumor cells being somewhat different from the primary tumor cells that arrived there. We distinguish between these two types of prostate cancer cells by calling those newly arrived cells early prostate cancer cells (PCe) and terming those that have been conditioned to the bone microenvironment late prostate cancer cells (PCl). The equations for each type of cancer cell is provided below.

2.3.1 Early Prostate Cancer Cells (PCe)

| (14) |

In equation (14), we assume that all cancer cells are initially introduced into the bone as PCe at a constant rate σPCe from the primary tumor site. Once in the bone microenvironment, these cells proliferate logistically at rate μPCe and carrying capacity PCmax. As PCe cells become accustomed to the bone, they begin to undergo phenotypic changes to become PCl cells at rate νPC or they become apoptotic at rate αPCe. Here, PC=PCe+PCl, representing the total population of PC cells.

2.3.2 Late Prostate Cancer Cells (PCl)

| (15) |

| (16) |

Late prostate cancer cells (PCl) evolve directly from PCe cells (first term in Equation (14)), proliferate logistically, and become apoptotic at rate αPCl. Because the proliferation of PCl cells is simultaneously controlled by both Wnt and TGF-β, we used the functional form similar to that described in Equation (2) to describe these effects. The parameter μPCl1 is the proliferation rate of PCl cells in the absence of Wnt and TGF-β; whereas μPCl2 represents the maximum ligand-dependent proliferation rate. The parameters KTGFβa3 and KWNTa2 represent the half-maximal concentrations of TGF-β and Wnt respectively, which are the ligand concentrations inducing a half-maximal cell response.

PCa growth in bone is regulated by a variety of signaling molecules. In the next section we derive equations for the roles of Wnt, DKK-1, and PSA in metastatic progression in the bone.

2.4 Prostate Cancer Signaling Molecule Equations

Dysregulation of Wnt signalling can lead to several types of cancer, including prostate cancer [31]. Further, prostate cancer-produced Wnts have been shown to induce osteoblastic activity in PCa bone metastases [15].

2.4.1 Wnt Proteints (WNT)

| (17) |

Wnt is naturally present in small concentrations in the body to regulate tissue generation. However, assume in equation (17) that its concentration is sufficiently low in adult males that we may consider natural Wnt production to be negligible. The first term describes Wnt production by all prostate cancer cells (PC=PCe+PCl) in order to alter the bone microenvironment with maximum production rate, βWNT. DKK-1 is an antagonist to Wnt production, with half-maximal concentration KDKK1. In the second term, we also include a natural degradation rate for Wnt, λWNT.

2.4.2 Dickkopf Wnt Signaling Pathway Inhibitor-1 (DKK1)

| (18) |

DKK-1 evolution in the prostate cancer system is primarily derived from production by OBp, which is activated by TGF-β at a maximum rate βDKK1 and half-maximal response KTGFβr1 [55]. DKK-1 is also produced, albeit in significantly smaller amounts, by PCe at rate . The third term is the natural degradation of DKK-1 at rate λDKK1.

2.4.3 PSA

| (19) |

Measurement of PSA is an important procedure in the metastatic work-up of prostate cancer patients [52]. In equation (19), we neglect natural bodily sources of PSA and focus exclusively on cancer cell synthesis, specifically late stage cancer cell synthesis, and assume that it occurs at rate βPSA. We also include natural degradation rate λPSA.

Equations (14) – (19) describe the progression of prostate cancer cells once they enter the bone. In summary, early prostate cancer cells, PCe, arrive in the bone and eventually transform into late cancer cells, PCl. All cancer cells produce Wnt and its overexpression induces differentiation of OBu to OBp to OBa and also induces PCl proliferation. Our goal is to use the full model to determine prostate cancer growth patterns in the bone and to investigate the blockage of key molecular pathways. Before embarking on this task, we first describe the homeostatic steady state analysis and parameter estimation for the model.

3 Parameter Estimation

Below, we introduce the parameter values associated with the mathematical model. Initially, we focus on the parameters for the bone remodeling model in the absence of cancer and then proceed to discuss parameters associated with modulation of the bone in response to tumor growth.

3.1 Steady State Calculations and Parameter Estimation for Bone Remodeling

Many of the parameters for the bone remodeling model are available in the existing literature. We have used a variety of sources to parameterize this model. A complete list of parameters values taken from the literature and their sources for the bone remodeling model can be found in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

Parameters Based on Literature for the Bone Remodeling Model

| Variable | Description | Value | textbfUnits | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| OBu | Uncommitted osteoblasts | 5.12 × 106 | # of cells | [49] |

| OCp | Osteoclast precursor cells | 2.00 × 109 | # of cells | [49] |

| αOBa | OBa apoptosis rate | 0.30 | per day | [49] |

| αOCa1 | OCa apoptosis rate (−TGFβ)1 | 0.30 | per day | |

| αOCa2 | OCa apoptosis rate (+TGFβ) | 1.2 | per day | [49] |

| βLTGFβ1 | LTGFβ transition rate (−PSA)2 | 6.00 | per day | [1] |

| βLTGFβ2 | LTGFβ transition rate (+PSA)2 | 6.00 | per day | [1] |

| βRANKL | RANKL production rate | 2.15 × 10−7 | pM per cell per day | [49] |

| βDKK1 | Natural DKK1 production rate | 4.35 × 10−7 | pM per cell per day | Calculated |

| βPTH | PTH production rate | 9.74 × 102 | pM per day | [49] |

| βPTHrP | PTHrP production rate | 1.28 × 10−7 | pM per cell per day | [9] |

| βOPG | OPG production rate | 2.06 × 10−6 | pM per cell per day | [49] |

| i | Calcium intake rate | 1.00 × 10−3 | M per day | [19, 28, 41]3 |

| SCa2+ | Normal calcium levels | 1.25 × 10−3 | M | [40] |

| OPGmax | Carrying capacity for OPG | 7.98 × 102 | pM | [49] |

| ρ | Maximum RANKL on OBp | 1.92 × 10−6 | pM per cell | [49] |

| KTGFβa1 | TGFβ-OBu activation constant | 4.28 × 10−4 | pM | [49] |

| KTGFβr1 | TGFβ-OBp repression constant | 2.49 × 10−4 | pM | [49] |

| KTGFβa2 | TGFβ-OCa activation constant | 4.28 × 10−4 | pM | [49] |

| KWNTa1 | Wnt-OBu activation constant4 | 4.28 × 10−4 | pM | |

| KWNTa2 | Wnt-OBp activation constant | 4.28 × 10−4 | pM | [9] |

| KRANKLa1 | RANKL-OCp activation constant | 47.9 | pM | [49] |

| KPTHtotalr1 | PTHtotal- OPG repression constant | 2.21 × 10−1 | pM | [49] |

| KA,OPG | Rate of RANKL binding to OPG | 5.68 × 10−2 | per pM | [49] |

| KA,RANK | Rate of RANKL binding to RANK | 7.19 × 10−2 | per pM | [49] |

| KPTHtotala1 | PTH-RANKL activation constant | 2.09 × 102 | pM | [49] |

| KDKK1 | DKK-1 repression constant4 | 4.28 × 10−4 | pM | |

| Kres | Bone resorption rate | 1.28 × 10−10 | % per cell per day | [49] |

| μ | TGFβ stored in the bone | 1.00 | pM per % | [49] |

| λLTGFβ | Latent TGFβ degradation rate | 11.09 | per day | [27] |

| λTGFβ | TGFβ degradation rate | 499.1 | per day | [27] |

| λPTH | PTHrP degradation rate (−PSA) | 3.84 × 102 | per day | [49] |

| λPTHrP1 | PTHrP degradation rate (−PSA) | 86.0 | per day | [9] |

| λPTHrP2 | PTHrP degradation rate (+PSA) | 60 | per pM per day | [9] |

| λOPG | OPG degradation rate | 4.16 | per day | [49] |

| λRANKL | RANKL degradation rate | 4.16 | per day | [49] |

Chosen to be the same as αOBa

Estimated based on values given in [1], adjusted for human bone.

These three together help establish an effective range for calcium with lower and upper bounds.

Chosen to be the same as

The following sections are calibrations of our new model’s parameters and steady states in the absence of prostate cancer cells. In this situation, we expect the bone cells and chemical regulators to all approach normal, homeostatic levels.

3.1.1 Steady State Equations For Latent and Active TGF-β

The only completely new equations in the bone model without cancer cells are the ones for calcium, equation (6), and latent TGF-β, equation (7). Therefore, we determine the normal steady state levels of calcium, latent TGF-β, and active TGF-β to ensure homeostasis below. All other steady state analysis can be found in [49].

We define the calcium steady state to equal regular hormonal levels without cancer, SCa2+ = 1.25 × 10−3M, and we know the bone resorption rate Kres from Table 3. We can now solve for bone formation rate Kform by considering equation (5) and ensuring that total bone volume remain at steady state as follows:

| (20) |

When there are no prostate cancer cells in the bone and when PSA levels are negligible, equations (7) and (8) give the following steady state levels of latent and active TGF-β:

| (21) |

3.1.2 Calculation of Bone Cell Differentiation Rates

Now that we have steady state relations for all of the bone-related proteins, we can use them to derive relations for the differentiation rates of OBu, OBp, and OCp cells in the absence of cytokines produced by prostate cancer cells (e.g. Wnt, PSA, PTHrP, and DKK-1). This allows us to estimate the values of these parameters that will ensure homeostasis when not exposed to cancer cells.

Solving (1) for the differentiation rate of the uncommitted cells we find:

| (22) |

Similarly, from equation (3) and (4) for the osteoblast and osteoclast precursor cells; respectively, we obtain:

| (23) |

By substituting known parameters and steady values for all cells and proteins, we are able to determine values for these differentiation rates that ensure that the cell populations achieve the correct homeostatic steady state values, which we use as initial conditions. The exact values for bone cell steady states can be found in Table 1. Our newly calculated parameter values are given in Table 4. The differences between our values and those computed by [49] can be attributed to our more detailed model of TGF-β dynamics, which were not previously considered.

Table 4.

Calculated Values for the Bone Remodeling Model

| Variable | Description | Calculated Value | Units | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| δOBu | OBu differentiation rate | 1.73 × 103 | per day | |

| δOBp1 | OBp differentiation rate | 2.65× 10−1 | per day | |

| δOCp | OCp differentiation rate | 3.20 × 10−1 | per day | |

| Kform | Bone formation rate | 2.26 × 10−11 | % per cell per day | |

| Q | Calcium released with 1% destruction of bone volume | 14.9398 |

|

|

3.1.3 Conversion Between Bone Volume and Calcium

In the following calculation of the conversion of bone marrow volume to calcium, we make several simplifying assumptions. We consider the skeleton to be composed of cylindrical bones (estimated by dimensions involved in calculating clavicle size) and we assume that bones are entirely marrow wrapped in cortical bone of constant thickness. We assume that all bone growth occurs radially outward, with no bones growing longer. We take all the calcium in the bone to be sequestered in the form of fully carbonated hydroxyapatite: Ca5(PO4)3CO3. For every mole of hydroxyapatite, there are five moles of Ca2+ ion bound to the matrix. The amount of calcium in moles is directly proportional to the moles of apatite, which can be converted into the mass of apatite via the division by apatite’s molar mass (545g/mol). Bone apatite mass is 0.65 times cortical bone mass. Therefore, to convert from the volume bone in cm3 to moles of calcium, we multiply the former by , the density of cortical bone. Blood volume is about .07 L/kg body mass. Using 70kg for an adult male weight, volume comes to 4.9 Liters. Ergo, each cubic centimeter of cortical bone dissolved into the bloodstream results in approximately 0.22 M increase in blood calcium concentration.

We derive an expression for Q, the amount of calcium released with 1% destruction of bone volume, by multiplying the 0.22M/cm3 by cortical bone volume in cubic centimeters divided by bone marrow volume in percent, and we obtain a conversion factor that is technically a function of bone volume. However, with the addition of bone volume calcium dependence, bone volume tends to remain relatively constant. Ergo, we substitute 100% for the dependence on bone marrow volume and obtain Q = 14.9398 M Ca2+/%Bone.

3.2 Parameter Estimation for Cancer Dynamics

In order to validate our approach that models both early (newly arrived in bone; PCe) and late (conditioned to the bone microenvironement; PCl) growth events, MC3T3 cells, a murine pre-osteoblast cell line, were grown in osteoblast differentiation media. After differentiation into osteoblasts, the media was refreshed to complete media and the cells were incubated for 24 hours at which time conditioned media was collected. Then the human prostate cancer cell lines, PC-3 and Du145, were plated and incubated in either normal complete medium with the addition of 10% FBS (to model the early stage) or a mixture of 50% complete medium and 50% MC3T3-conditioned medium with the addition of 10% FBS to the mixture (to model the late bone metastatic stage). After 24 hours of cell growth, cells were harvested into single cell suspensions. To determine the proliferative rate, cell suspensions were stained with the nuclear stain bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) and subjected to flow cytometry to determine the percent of proliferating cells. To determine apoptotic fraction, cells were stained with an antibody to poly(ADP) ribose polymerase (PARP) a marker for apoptosis, then subjected to flow cytometry to determine the PARP positive percent of the population.

The results of these experiments are given in Table 5 and validate the differences in the growth potential for early and late prostate cancer cells proposed in our model. We also use this data to compute the percentage differences in proliferation and apoptosis between the two cells types in order to estimate parameters for PCa growth in humans.

Table 5.

In Vitro Prostate Cancer Cell Growth Parameters

| Brdu-positive percentage | Proliferation rate per day | Apoptotic cells percentage | Apoptosis rate per day | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| DU145-CM | PCa late | 49.74% | DU145-CM | PCa late | 0.16% |

| DU145-con | PCa early | 43.14% | DU145-con | PCa early | 0.07% |

| PC3-CM | PCa late | 26.5% | PC3-CM | PCa late | 0.42% |

| PC3-con | PCa early | 26.99% | PC3-con | PCa early | 0.31% |

Our mathematical model describes in vivo prostate cancer growth in humans, therefore parameters associated with PCa growth must be adjusted accordingly. Although difficult to accurately measure in humans, prostate cancer is known to be slow-growing, displaying tumor volume doubling times of months or years [22]. The doubling time for radical prostatectomy specimens of human prostate cancer, as opposed to the cell lines described above, has been reported to range from 0.6 to 3.6 months [51]. It has also been reported that serum PSA levels are proportional to the volume of prostate cancer and that the PSA doubling time in untreated patients should reflect the tumor volume doubling time [42]. In [37], data from 250 prostate cancer patients is reported to exhibit a median PSA doubling time 45 days (range 4.7–1108 days). We selected 30 days as representative doubling time within these ranges (changing this value does not change the qualitative features of our results) and computed the PCe proliferation rate (μPCe) using this baseline. However, because this growth rate is associated with tumors in an androgen rich environment, which is not the initial microenvironment they encounter in the bone, we scale this rate based on the assumption that androgen induces a 4-fold increase in proliferation.

The ligand-independent PCl proliferation rate (μPCl1) is assumed to be the sum of μPCe and the percent difference in average proliferation for PCl and PCe from the in vitro data. The ligand-dependent PCl proliferation rate is again computed based on the assumption of a 4-fold increase in proliferation due to ligand stimulation. Although the in vitro data show that, on average, a very small percentage of cells are apoptotic per day, we estimate the early prostate cancer cell death rate (αPCe) by assuming that 10% of cells are apoptotic per day during early metastatic tumor growth in humans due to the initial incompatibility of the bone microenvironment. Similar to the derivation of μPCl1, the late prostate cancer cell apoptosis rate (αPCl) is assumed to be the sum of αPCe and the percent difference in the average apoptosis for PCl and PCe from the in vitro data. Finally, although the PCe to PCl transition rate (νPC) is not known experimentally we assume that 1% transition per day. A full list of the parameters for the model equations that describe the dynamics of tumor growth (equations 14–19) are given in Table 6.

Table 6.

Parameters for the Model With Cancer Dynamics

| Variable | Description | Value | Units | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| αPCe | PCe apoptosis rate1 | 2.34 × 10−3 | per day | ||

| αPCl | PCl apoptosis rate1 | 4.27 × 10−3 | per day | ||

| σPCe | PCe translocation rate2 | 100 | cells per day | ||

| μPCe | PCe proliferation rate1 | 4.67 × 10−3 | per day | ||

| μPCl1 | PCl proliferation rate (−Ligands)1 | 4.39 × 10−3 | per day | ||

| μPCl2 | PCl proliferation rate (+Ligands)1 | 1.76 × 10−2 | per day | ||

| βLTGFβ2 | LTGFβ transition rate (+PSA)3 | 6.00 | per day | ||

| βWNT | Wnt production rate | 6.39 × 10−9 | pM per cell per day | [9] | |

|

|

DKK1 production rate4 | 6.39 × 10−9 | pM per cell per day | ||

| βPSA | PSA production rate | 6.39 × 10−9 | pM per cell per day | [9] | |

| PCmax | Carrying capacity for PC5 | 2.6 × 1012 | # of cells | ||

| νPC | PCe transition rate | 0.01 | per day | ||

| KPSAa1 | PSA-LTGFβ activation constant4 | 4.28 × 10−4 | pM | ||

| KTGFβa3 | TGFβ-PCl activation constant4 | 4.28 × 10−4 | pM | ||

| KWNTa3 | Wnt-PCl activation constant4 | 4.28 × 10−4 | pM | ||

| λWNT | Wnt degradation rate | 2 | per day | [9] | |

| λDKK1 | DKK1 degradation rate4 | 2 | per day | ||

| λPSA | PSA degradation rate | 4.0 | per day | [9] | |

Estimated as described in Section 3.2.

Based on 5 liters blood per person and 1 disseminated tumor cell (DTC) per 5 ml, we can estimate 1000 DTC per human marrow. Assuming a 10% apoptosis rate and steady state DTC, we arrive at 100 cells translocating to the bone per day

Chosen to the same as βLTGFβ1 so that the overexpression of PSA can at most double the maximum transition rate

Chosen to be the same as the value used for WNT

4 Results

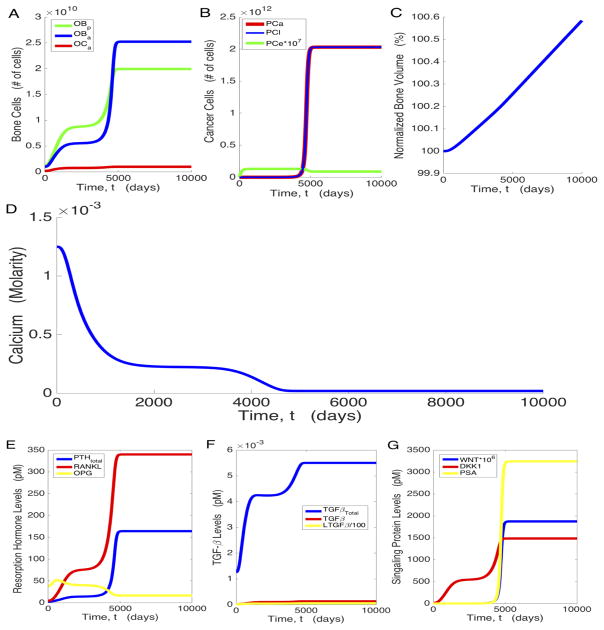

Our model formulation and parameter choices ensure the bone cell populations and bone volume start at and remain in their respective homeostatic steady states, before the introduction of prostate cancer cells (results not shown). When cancer cells are introduced, several hormonal changes disturb this equilibrium, causing the system to create an environment more hospitable for the cancer. For our baseline parameters, when prostate cancer cells are present, we see in Figure 2 that the system approaches a steady state associated with high osteogenesis (characterized by a 25-fold increase in OBa in Figure 2a) and high tumor burden (Figure 2b). Though initially PCe is the dominant tumor cell type, the high osteogenic state is ultimately characterized by a significantly higher ratio of PCl to PCe (from approximately 1:106 at the low osteogenic state to approximately 10:1 at the high osteogenic state).

Figure 2.

PC growth and modification of the bone microenvironment. Temporal dynamics of osteoblasts and osteoclasts (a), prostate cancer cells (b); bone volume (c); calcium levels in the bloodstream (d); chemical mediators of osteogenesis, PTH, RANKL, and OPG (e); active and latent TGF-β (f); and WNT, DKK1, and PSA (g).

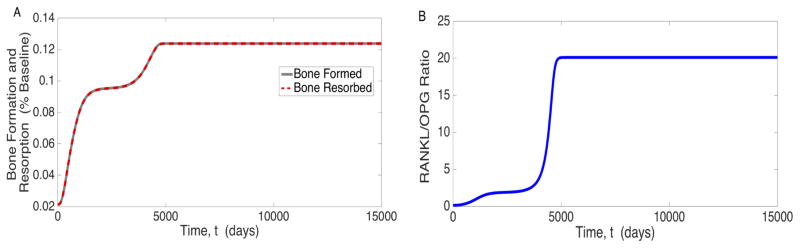

Figure 2 also shows how the chemical mediators of cancer and bone growth evolve with time. PTH increases to more than 60 times its pre-cancer value, and the RANKL/OPG ratio, an important effector of bone resorption, increases from the pre-cancer level 0.1233 to 20.5526 at the high osteogenic state in the model (Figure 2e). This imbalance stimulates osteoclastogenesis, which is increased by a factor of about 6 at steady state (Figure 2a). TGF-β increases over time (Figure 2f), which is indicative of elevated bone turnover. This is substantiated by Figure 3, which shows that bone production and resorption both rose substantially. The pre-cancer value of bone formation is set to be equal to the pre-cancer value of bone resorption, resulting in homeostasis as shown in equations (5) and (20). The slope of the bone volume plot in Figure 2c, when cancer is present, is exactly equal to the amount of bone created minus the amount of bone destroyed. This rapid bone turnover ultimately results in net bone creation (a 0.6% increase over the entire body as shown in Figure 2c), which requires calcium, depleting bloodstream reserves (Figure 2d).

Figure 3.

Plot of a) Bone Turnover and b) RANKL/OPG ratio in response to prostate cancer subversion of the bone microenvironment.

Our results agree with those in [49] on several key points. Specifically, when cancer cells are present, RANKL levels and bone cell numbers are increased, while OPG levels are decreased. The temporal evolution of bone volume is different between this model and that in [49]. Here we see that volume increases over time while [49] predicts a net decrease in bone. This difference is consistent with the fact that [49] describes a bone-resorbing cancer, whereas this model focuses on prostate cancer, which is known to produce bone [48].

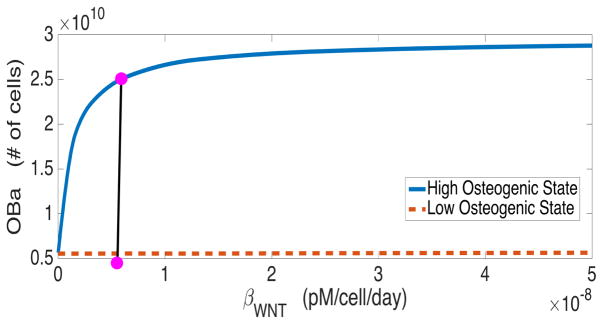

An interesting feature of the new model is the potential for the system to approach a steady state associated with low osteogenesis (characterized by only a 5-fold increase in OBa) and a lower tumor burden (See Figure 2a). Our numerical analysis of the system suggests that a saddle-node bifurcation occurs when βWNT = 0 and that the addition of any Wnt at all to the system renders the low osteogenic state unstable. For the parameters of cancer progression without intervention (baseline parameters), we see that while PCe is the dominant cancer cell type and DKK-1 is almost completely suppressing Wnt, the system attempts to approach the low osteogenic steady state (Figure 2). However, as PCl begins to take over and Wnt levels rise, the system is forced to the stable steady state associated with high osteogenesis. This suggests that Wnt is a major driving force in bone remodeling in prostate cancer and DKK-1 may be an important roadblock in cancer development.

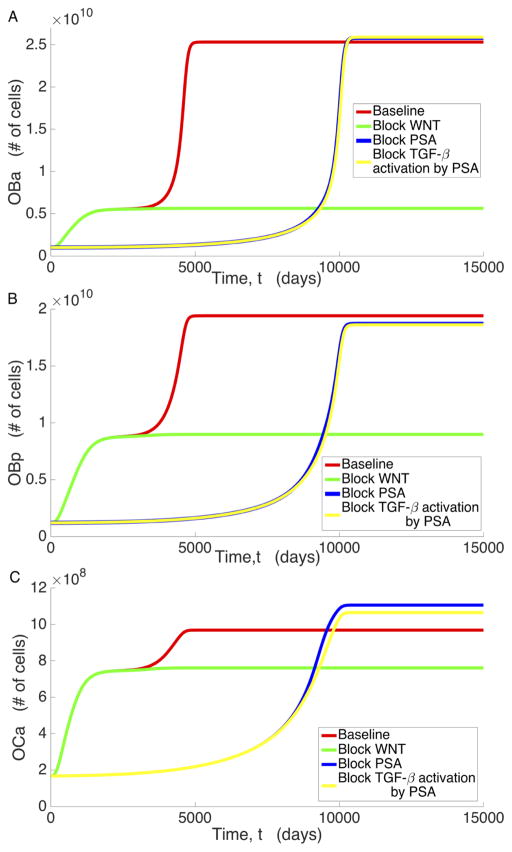

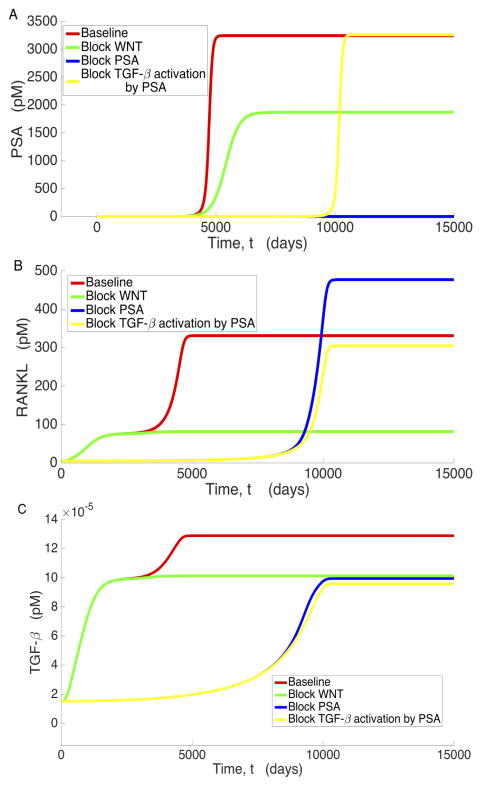

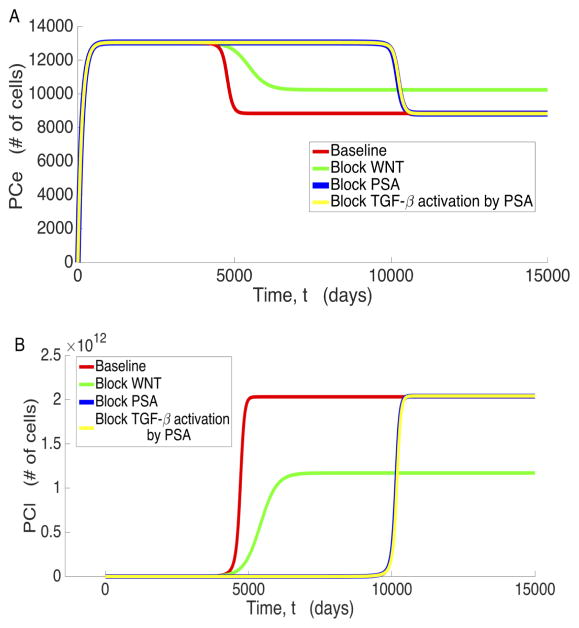

To analyze the mechanisms that contribute to the existence of the low osteogenic state, we examine the significant variables associated with prostate cancer metastasis under various conditions: unimpeded bone and cancer growth (baseline), Wnt inhibition (βWNT = 0), PSA inhibition (βPSA = 0), and blockage of PSA’s activation of TGF-β (βLTGFβ2= 0). These results are displayed in Figures 4 through 6, where we observe that all the variables plotted present distinct steady states characterized by the low osteogenic state differing by a magnitude of at least 2, in most cases, from the high osteogenic state. However, we also observe that the existence and/or stability of the low and high osteogenic states with respect to βWNT and βLTGFβ2 for PCs (Figure 5) and PSA (Figure 6a) is different than the other system variables. In Figure 4 we see that for OBa cells, Wnt inhibition results in the existence and stability of the smaller, low osteogenic steady state, while blockage of PSA catalyzed TGF-β activation (βLTGFβ2) eliminates the existence of this steady state and the approach to the high osteogenic state is delayed. Most of the variables react similarly to OBa when Wnt production and PSA activation of TGF-β are prevented. We shall refer to this behavior, where a variable presents two osteogenic states such that the lower occurs around t = 2000 days and depends on PSA activation of TGF-β, while the latter depends on the presence of Wnt and occurs around t = 5000 days, as the canonical behavior.

Figure 4.

Behavior of a) OBa, b) OBp, c) OCa under baseline conditions, blocking WNT, blocking PSA, and blocking PSA’s activation of TGF-β.

Figure 6.

Behavior of a) PSA, b) RANKL, and c) TGFβ under baseline conditions, blocking WNT, blocking PSA, and blocking PSA’s activation of TGFβ.

Figure 5.

Behavior of a) PCe and b) PCl under baseline conditions, blocking WNT, blocking PSA, and when blocking PSA’s activation of TGF-β.

Further inspection of the model simulations reveals that not all variables exhibit this canonical behavior. Both PCl and PSA deviate from the canonical behavior in that they do not transiently approach their low osteogenic state when Wnt is present in the system. Instead, they exceed it without pause, only approaching the low osteogenic state when Wnt production is zero. This occurs because by the time PCl and PSA begin to increase, the rest of the system is already near the high osteogenic state. Similar to canonical behavior, setting βLTGFβ2 to zero does indeed instigate a delay in reaching the high osteogenic state for both PCl and PSA, and inhibiting PSA production has a similar effect to inhibiting PSA mediated TGF-β activation for PCl. However, while reducing βLTGFβ2 does delay the approach to the high osteogenic state for PCe, inhibiting Wnt results in a high osteogenic state that is characterized by an increase in the number of PCe cells. This is most likely caused by decreased competition with PCl and helps emphasize that Wnt is critical for full transition of the disease from the low osteogenic state to the high osteogenic state.

For variables that demonstrate canonical behavior, the high osteogenic state diverges from the low osteogenic state because of the presence of Wnt in the system. As shown in Figure 7, there is a single stable state when Wnt is not produced, but as the Wnt production rate increases from zero, the low osteogenic state becomes unstable and a stable high osteogenic state emerges.

Figure 7.

Bifurcation diagram showing the steady state active osteoblasts (OBa) with respect to WNT production rate (βWNT). The dot represents the baseline value used in simulations.

However, these data imply that there is a causative agent that encourages cellular growth and microenvironment remodeling before the evolution of significant amounts of Wnt, and when this agent is blocked, the microenvironment should effectively stabilize until Wnt increases. In our model, PSA appears to be this agent, as blocking it eliminates the transient approach to the low osteogenic state and results in a significant delay in reaching the stable high osteogenic state. This temporal profile is the result of slow temporal increases in Wnt as PCl cells increase; however, it is not able to have its full protumorigenic effect in the presence of DKK-1 until the shift to the high osteogenic state occurs around 8000 days (Figure 4a).

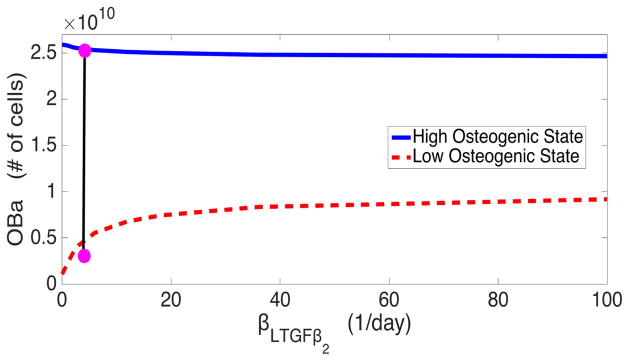

We conjecture that PSA accelerates osteogenesis in the model via the catalysis of latent TGF-β into its active form. We test this hypothesis through bifurcation analysis, sampling the low and high osteogenic states at different values of βLTGFβ2, the maximum rate of PSA mediated activation of TGF-β. The bifurcation diagram shown in Figure 8 reveals two important details about PSA’s activation of TGF-β. Firstly, when PSA is entirely inhibited from activating TGF-β, the low osteogenic state is essentially identical to the cancer-free steady state. This implies that the additional activation of TGF-β is critical for the establishment of a low osteogenic state. Secondly, the analysis reveals that this additional activation has little effect on the high osteogenic state, indicating that while this activation is important for accelerating the growth of cancer, it has little impact on final tumor burden. This implies that there is a requirement for TGF-β levels to rise before the high osteogenic state can be established, which is consistent with the results found in [10] detailing that TGF-β inhibition can help ameliorate metastasis.

Figure 8.

Bifurcation diagram of steady state active osteoblasts (OBa) with respect to maximum rate of PSA mediated activation of TGF-β (βLTGFβ<sub>2</sub>). The dot represents the baseline value used in simulations.

Taken together, the model predictions agree with experimental observations on many counts, both quantitatively and qualitatively. We therefore suggest that it is able to characterize the progression of prostate cancer metastasis and its impact on the bone microenvironment.

Discussion

In this paper, we have developed a mathematical model of metastatic tumor growth in an effort to explain the dynamic interplay between prostate cancer and bone. The model modifies and extends several previously published mathematical investigations into tumor growth in the bone microenvironment. Important new features of this model include a greatly altered bone microenvironment, driven by increases in both PSA and Wnt. Interestingly, this new model admits solutions with multiple identifiable states: a high osteogenic state and a low osteogenic state. The low osteogenic state is characterized by lower tumor burden, a less altered bone environment, and a high amount of DKK-1 relative to Wnt. Numerical simulations suggest that the low osteogenic state emerges because excess PSA increases the activation of TGF-β, and bone remodeling is stalled at that state until sufficient amounts of Wnt are produced. This increase in Wnt provokes the system to advance into a high osteogenic state, which is characterized by high tumor burden, a highly modified bone microenvironment, and larger amounts of Wnt relative to DKK-1.

In order to improve patient outcomes for aggressive cancers, an increasing amount of research is now being aimed at understanding the molecular biology of the tumor growth and metastasis in an attempt to selectively target pathways involved in accelerated tumor growth. As shown in Figure 5, blocking Wnt at the tumor site has the potential to be an effective anticancer measure, locking the system into the low osteogenic state. When PSA is first high enough to become diagnostically relevant, Wnt is still extremely low in the system. Hence, the system has yet to switch from the low osteogenic state to the high osteogenic state. As Wnt production is decreased, the high osteogenic state begins to approach the low osteogenic state, and the high osteogenic state becomes identical to the low osteogenic state when Wnt production is completely blocked. Figure 5 also shows that blocking Wnt results in a larger proportion of the total prostate cancer cell population being in the PCe cell state and the tumor burden is decreased overall. This eases the burden on other avenues of treatment, improving patient prognosis. Fully inhibiting DKK-1 degradation has the same effect as blocking Wnt entirely, again producing the same effect on cancer that occurs in Figure 5: the low osteogenic state is now the ultimate state of the system, as there is insufficient Wnt to overcome DKK-1. Increasing DKK-1 production drastically eventually causes the same effect shown in Figure 5, but DKK1- production must be increased to clinically infeasible levels that to achieve this.

The final cellular and chemical profile for our post-cancer model is consistent with several of the results obtained in [39]. As shown in Figure 3, the final value for the RANKL/OPG ratio falls within 19.62 ± 6.52, in agreement with [39] for late stage prostate cancer metastasis. They also observe an increase in TGF-β and propose that it is the result of increased bone turnover. As shown in Figure 2, TGF-β is indeed significantly increased in our model and the hypothesis of increased bone turnover in [39] is supported by Figure 3. We also note that the low osteogenic state agrees with the general results in [39], with an increased RANKL/OPG ratio (Figure 3B), TGF-β (Figure 2F), and bone turnover (Figure 3A). Importantly, all three of these values fall between the pre-cancer and high osteogenic state values, emphasizing the transient nature of the low osteogenic state. Although our results agree with those in [39] on many counts, there is one noteworthy point for further discussion. Specifically, in [39], they observed relatively constant calcium levels while the model presented here predicts vastly decreased calcium levels. However, a case study in [46] shows that calcium levels can decrease due to to cancer metastasis.

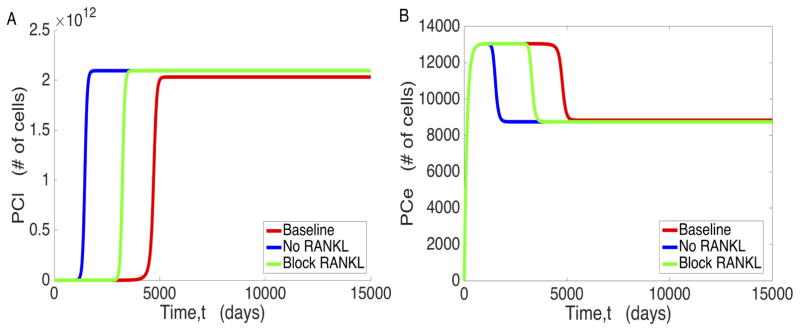

We also explored the possibility of RANKL being an effective potential inhibitor of cancer cell proliferation, as suggested in [2]. We tested two distinct possibilities: one where RANKL is completely blocked from the start, and the other where RANKL is completely blocked at diagnostically significant levels of PSA. As shown in Figure 9, however, both of these not only failed to prevent PC proliferation, they also exacerbated the progression of PCe to PCl and ultimately accelerated the progression of the cancer overall.

Figure 9.

The effects of RANKL interventions on a) proliferation of PCl and b) proliferation of PCe. The No RANKL curves represent RANKL blockage from time t = 0, and Block RANKL represents RANKL blockage from the time when PSA is diagnostically significant, at 0.118 pM (derived from the standard 4 ng/mL used as a benchmark in PSA testing [50].)

The major prediction of this model is the existence of low and high osteogenic states that are markedly different from one another. Measuring cell counts directly over the course of disease would be the most precise method of determining whether this prediction holds; however, this is not particularly viable, as it is impractical to collect bone samples over the entire course of the disease. Instead, the most viable method of testing this model would be to attempt to block Wnt production in metastatic individuals in a doubleblind clinical trial. Should this model hold, blocking Wnt production should decrease tumor burden significantly in the experimental group. However, a more directly measurable result of this is the effect on TGF-β, whose levels are more easily measurable in a laboratory environment [26]. If the model predictions are correct, TGF-β levels should drop upon treatment with Wnt inhibitory drugs, as shown in Figure 6. It is also noteworthy that our model’s prediction of a low osteogenic state could provide a partial explanation for the survivability of prostate cancer before it reaches Stage 4, as metastasis is limited at the low osteogenic state. The abrupt decrease in survivability upon reaching Stage 4 can then be explained by a shift to the high osteogenic state. If this model is validated, new treatment options can be developed with a focus on anti-Wnt protocols. Although the significance of Wnt and RANKL as contributors to tumor subversion of the bone microenvironment is unquestionable, we still do not fully understand how therapies targeted against these proteins will work in vivo. Continued modeling efforts in this direction have the potential to shed light on such important issues.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shuichi Takayma for helpful discussions and Beatrix Balogh for early efforts on this project. This work was supported by NIH P01 CA093900 (ETK), UM M-Cubed (ETJ, TLJ), and the Simon’s Foundation (TLJ).

References

- 1.Ahamed J, Burg N, Yoshinaga K, Janczak CA, Rifkin DB, Coller BS. In vitro and in vivo evidence for shear-induced activation of latent transforming growth factor-β1. Blood. 2008;112:3650–3660. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-151753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Araujo A, Cook LM, Lynch CC, Basanta D. An Integrated Computational Model of the Bone Microenvironment in Bone-Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74(9):2391–2401. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asadi F, Farraj M, Sharifi R, Malakouti S, Antar S, Kukreja S. Enhanced expression of parathyroid hormone-related protein in prostate cancer as compared with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Hum Pathol. 1996;27(12):1319–23. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(96)90344-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blair HC, Robinson LJ, Huang CL, Sun L, Friedman PA, Schlesinger PH, Zaidi M. Calcium and bone disease. Biofactors. 2011;37(3):159–67. doi: 10.1002/biof.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonewald LF, Wakefield L, Oreffo RO, Escobedo A, Twardzik DR, Mundy GR. Latent forms of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF beta) derived from bone cultures: identification of a naturally occurring 100-kDa complex with similarity to recombinant latent TGF beta. Mol Endocrinol. 1991;5(6):741–51. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-6-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyce BF, Xing L. The RANKL/RANK/OPG pathway. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2007;5(3):98–104. doi: 10.1007/s11914-007-0024-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown EM, Wilson RE, Thatcher JG, Marynick SP. Abnormal calcium-regulated PTH release in normal parathyroid tissue from patients with adenoma. Am J Med. 1981;71:565–570. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(81)90207-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bubendorf L, Schopfer A, Wagner U, Sauter G, Moch H, Willi N, Gasser TC, Mihatsch MJ. Metastatic patterns of prostate cancer: an autopsy study of 1,589 patients. Hum Pathol. 2000;31(5):578–83. doi: 10.1053/hp.2000.6698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buenzli PR, Pivonka P, Gardiner BS, Smith DW. Modelling the anabolic response of bone using a cell population model. J Theor Biol. 2012;307:42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cook LM, Aruajo A, Pow-Sang JM, Budzevich MM, Basanta D, Lynch CC. Predictive computational modeling to define effective treatment strategies for bone metastatic prostate cancer. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29384. doi: 10.1038/srep29384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cook LM, Shay G, Aruajo A, Lynch CC. Integrating new discoveries into the “vicious cycle” paradigm of prostate to bone metastases. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2014;33(0):511–525. doi: 10.1007/s10555-014-9494-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cramer SD, Chen Z, Peehl DM. Prostate specific antigen cleaves parathyroid hormone-related protein in the PTH-like domain: inactivation of PTHrP-stimulated cAMP accumulation in mouse osteoblasts. J Urol. 1996;156(2 Pt 1):526–531. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199608000-00076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crockett JC, Rogers MJ, Coxon FP, Hocking LJ, Helfrich MH. Bone remodelling at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:991–998. doi: 10.1242/jcs.063032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Day TF, Guo X, Garrett-Beal L, Yang Y. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in mesenchymal progenitors controls osteoblast and chondrocyte differentiation during vertebrate skeletogenesis. Dev Cell. 2005;8:739–750. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dai J, Hall CL, Escara-Wilke J, Mizokami A, Keller JM, Keller ET. Prostate cancer induces bone metastasis through Wnt-induced bone morphogenetic protein-dependent and independent mechanisms. Cancer research. 2008;68(14):5785–5794. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dallas SL, Rosser JL, Mundy GR, Bonewald LF. Proteolysis of latent transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta )-binding protein-1 by osteoclasts. A cellular mechanism for release of TGF-beta from bone matrix. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(24):21352–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111663200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dallas SL, Zhao S, Cramer SD, Chen Z, Peehl DM, Bonewald LF. Preferential production of latent transforming growth factor beta-2 by primary prostatic epithelial cells and its activation by prostate-specific antigen. J Cell Physiol. 2005;202(2):361–70. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Day TF, Guo X, Garrett-Beal L, Yang Y. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in mesenchymal progenitors controls osteoblast and chondrocyte differentiation during vertebrate skeletogenesis. Dev Cell. 2005;8(5):739–750. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deng XR, Zhang YF, Wang TG, Xu BH, Sun JC, Zhao LB, et al. Serum calcium level is associated with brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity in middle-aged and elderly Chinese. Biomed Environ Sci. 2014;27(8):594–600. doi: 10.3967/bes2014.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Filvaroff E, Erlebacher A, Ye J, Gitelman SE, Lotz J, Heillman M, Derynck R. Inhibition of TGF-beta receptor signaling in osteoblasts leads to decreased bone remodeling and increased trabecular bone mass. Development. 1999;26(19):4267–79. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.19.4267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fournier PG, Juarez P, Jiang G, Clines GA, Niewolna M, Kim HS, Walton HW, Peng XH, Liu Y, Mohammad KS, Wells CD, Chirgwin JM, Guise TA. The TGF-? Signaling Regulator PMEPA1 Suppresses Prostate Cancer Metastases to Bone. Cancer Cell. 2015;27(6):809–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friberg S, Mattson A. On the Growth Rates of Human Malignant Tumors: Implications for Medical Decision Making. J Surg Oncol. 1997;65:284–297. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199708)65:4<284::aid-jso11>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall CL, Daignault SD, Shah RB, Pienta KJ, Keller ET. Dickkopf-1 expression increases early in prostate cancer development and decreases during progression from primary tumor to metastasis. Prostate. 2008;68(13):1396–1404. doi: 10.1002/pros.20805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heath DJ, Chantry AD, Buckle CH, Coulton L, Shaughnessy JD, Jr, Evans HR, Snowden JA, Stover DR, Vanderkerken K, Croucher PI. Inhibiting Dickkopf-1 (Dkk1) removes suppression of bone formation and prevents the development of osteolytic bone disease in multiple myeloma. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24(3):425–36. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.081104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang JC, Sakata T, Pfleger LL, Bencsik M, Halloran BP, Bikle DD, Nissenson RA. PTH differentially regulates expression of RANKL and OPG. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(2):235–44. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.0301226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jurukovski V, Dabovic B, Todorovic V, Chen Y, Rifkin DB. Methods for measuring TGF-b using antibodies, cells, and mice. Methods Mol Med. 2005;117:161–75. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-940-0:161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaminska B, Wesolowska A, Danilkiewicz M. TGF beta signalling and its role in tumour pathogenesis. Acta Biochim Pol. 2005;52(2):329–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanagal DV, Rajesh A, Rao K, Devi UH, Shetty H, Kumari S, et al. Levels of Serum Calcium and Magnesium in Pre-eclamptic and Normal Pregnancy: A Study from Coastal India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(7):OC01–4. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8872.4537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karsenty G, Kronenberg HM, Settembre C. Genetic control of bone formation. Ann Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2009;25:629–648. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krishnan V, Bryant HU, MacDougald OA. Regulation of bone mass by Wnt signaling. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2006;116(5):1202–1209. doi: 10.1172/JCI28551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kypta RM, Waxman J. Wnt/β-catenin signalling in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2012;9(8):418–28. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2012.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liao J, Li X, Koh AJ, Berry JE, Thudi N, Rosol TJ, Pienta KJ, McCauley LK. Tumor expressed PTHrP facilitates prostate cancer-induced osteoblastic lesions. Int J Cancer. 2008;123(10):2267–78. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Langdahl BL, Knudsen JY, Jensen HK, Gregersen N, Eriksen EF. A sequence variation: 713-8delC in the transforming growth factor-beta 1 gene has higher prevalence in osteoporotic women than in normal women and is associated with very low bone mass in osteoporotic women and increased bone turnover in both osteoporotic and normal women. Bone. 1997;20:289–294. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(96)00363-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Logothetis CJ, Lin SH. Osteoblasts in prostate cancer metastasis to bone. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(1):21–28. doi: 10.1038/nrc1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mundy GR, Guise TA. Hormonal control of calcium homeostasis. Clin Chem. 1999;45(8 Pt 2):1347–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nielsen PK, Rasmussen AK, Butters R, Feldt-Rasmussen U, Bendtzen K, Diaz R, Brown EMm, Olgaard K. Inhibition of PTH Secretion by Interleukin-1? in Bovine Parathyroid Glandsin VitroIs Associated with an Up-Regulation of the Calcium-Sensing Receptor mRNA. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1997;238(3):880–885. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oudard S, Banu E, Scotte F, Banu A, Medioni J. Prostate-specific antigen doubling time before onset of chemotherapy as a predictor of survival for hormone-refractory prostate cancer patients. Annals of Oncology. 2008;18(11):1828–1833. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pivonka P, Zimak J, Smith DW, Gardiner BS, Dunstan CR, Sims NA, Martin TJ, Mundy GR. Model structure and control of bone remodeling: a theoretical study. Bone. 2008;43(2):249–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roato I, D’Amelio P, Gorassini E, Grimaldi A, Bonello L, Fiori C, et al. Osteoclasts Are Active in Bone Forming Metastases of Prostate Cancer Patients. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(11):e3627. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, et al., editors. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium: Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. National Academies Press (US); 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sanchis-Gomar F, Salvagno GL, Lippi G. Inhibition of xanthine oxidase and exercise on serum uric acid, 25(OH)D3, and calcium concentrations. Clin Lab. 2014;60(8):1409–11. doi: 10.7754/clin.lab.2013.130830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmid HP, McNeal JE, Stamey TA. Observations on the doubling time of prostate cancer. The use of serial prostate-specific antigen in patients with untreated disease as a measure of increasing cancer volume. Cancer. 1993;71(6):2031–40. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930315)71:6<2031::aid-cncr2820710618>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.The Seer database: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/prost.html

- 44.Silberstein JL, Pal SK, Lewis B, Sartor O. Current clinical challenges in prostate cancer. Trans Androl and Urol. 2013;2(3):122–136. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2013.09.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simonet WS, Lacey DL, Dunstan CR, Kelley M, Chang MS, et al. Osteoprotegerin: a novel secreted protein involved in the regulation of bone density. Cell. 1997;89(2):309–19. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tandon PK, Rizvi AA. Hypocalcemia and parathyroid function in metastatic prostate cancer. Endo Prac. 2005;11(4):254–258. doi: 10.4158/EP.11.4.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Teitelbaum SL. Osteoclasts: what do they do and how do they do it? Am J Pathol. 2007;170:427–435. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vela I, Gregory L, Gardiner EM, Clements JA, Nicol DL. Bone and prostate cancer cell interactions in metastatic prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2007;99(4):735–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Y, Pivonka P, Buenzli PR, Smith DW, Dunstan CR. Computational Modeling of Interactions between Multiple Myeloma and the Bone Microenvironment. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(11):e27494. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Welch HG, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Prostate-Specific Antigen Levels in the United States: Implications of Various Definitions for Abnormal. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1132–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Werahera PN, Glode LM, La Rosa FG, Lucia MS, Crawford ED, et al. Proliferative Tumor Doubling Times of Prostatic Carcinoma, Prostate Cancer. 2011;2011:7. doi: 10.1155/2011/301850. Article ID 301850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wolff JM, Zimny M, Borchers H, Wildberger J, Buell U, Jakse G. Is prostate-specific antigen a reliable marker of bone metastasis in patients with newly diagnosed cancer of the prostate? Eur Urol. 1998;33(4):376–81. doi: 10.1159/000019619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xing L, Boyce BF. Regulation of apoptosis in osteoclasts and osteoblastic cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;328(3):709–720. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yavropoulou MP, Yovos JG. The role of the Wnt signaling pathway in osteoblast commitment and differentiation. Hormones. 2007;6:279–294. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1111024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhu Y, Sun Z, Han Q, Liao L, Wang J, Bian C, Li J, Yan X, Liu Y, Shao C, Zhao RC. Human mesenchymal stem cells inhibit cancer cell proliferation by secreting DKK-1. Leukemia. 2009;23(5):925–933. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]