Abstract

The goal of this project was to explore family communication dynamics and their implications for smoking cessation. We conducted 39 in-depth dyadic and individual qualitative interviews with 13 immigrant smoker–family member pairs of Vietnamese (n = 9 dyads, 18 individuals) and Chinese (n = 4 dyads, 8 individuals) descent, including seven current and six former smokers and 13 family members. All 13 dyadic and 26 individual interviews were analyzed using a collaborative crystallization process as well as grounded theory methods. We identified three interrelated pathways by which tobacco use in immigrant Vietnamese and Chinese families impacts family processes and communication dynamics. Using a two-dimensional model, we illustrate how the shared consequences of these pathways can contribute to a dynamic of avoidance and noncommunication, resulting in individual family members “suffering in silence” and ultimately smoking being reinforced. We discuss the implications of these findings for development of smoking cessation interventions.

Keywords: Asian American, family communication, qualitative research, smoking cessation

Tobacco use remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, accounting for approximately 6 million deaths per year globally (World Health Organization, 2015). Even though the overall smoking prevalence rate among adults in the United States has declined over the past decade to 17.8% in 2013 (Jamal et al., 2014), the prevalence rate of current smoking remains high among some Asian American groups, particularly among Asian American men with limited English proficiency, lower acculturation, and lower educational attainment (An, Cochran, Mays, & McCarthy, 2008; Chae, Gavin, & Takeuchi, 2006; Choi, Rankin, Stewart, & Oka, 2008; Kim, Ziedonis, & Chen, 2007; Tang, Shimizu, & Chen, 2005; Tong, Gildengorin, Nguyen, Tsoh, Modayil, et al., 2010; Tong, Nguyen, Vittinghoff, & Perez-Stable, 2008; Zhang & Wang, 2008). A multiyear (2009–2011) REACH US Risk Factor Survey conducted in English and multiple Asian languages with 3,215 Asian Americans (69% Chinese, 12% Koreans) residing in New York City showed that Korean American men had the highest smoking prevalence (36%) when compared with Chinese men (18%) and Indian men (10%; Li, Kwon, Weerasingh, Rey, & Trinh-Shevrin, 2013). However, when data were disaggregated by residence, Chinese men living in Sunset Park, a region with the highest concentrations of new Chinese immigrants in New York City, had the highest smoking prevalence (40%). The 2011–2012 California Health Interview Survey, the largest statewide survey conducted in multiple languages, revealed that Vietnamese and Chinese men with limited English proficiency had the highest smoking prevalence, 43% and 32%, respectively, when compared with other racial/ethnic groups combined (California Health Interview Survey, 2013). Population-based studies have documented a wide range of smoking prevalence rates among Asian American men subpopulations; however, these studies have consistently revealed a large gender difference in smoking prevalence, where Asian American men smoked at higher rates than Asian American women (<5% smoking prevalence reported in most Asian women subpopulations; Gorman, Lariscy, & Kaushik, 2014; Li et al., 2013).

Comprehensive culturally tailored interventions are urgently needed to adequately address the disease burden caused by tobacco (Chae et al., 2006). In addition to its associated health risks for smokers, secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure affects the health of family members (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014). As of 2007, only half of U.S. households with both smokers and children had home smoking bans (Mills, White, Pierce, & Messer, 2011). Studies have found that Asian American households report higher levels of home smoking bans, ranging from 58% (Tong, Tang, Tsoh, Wong, & Chen, 2009) to 90% (Tong, Gildengorin, Nguyen, Tsoh, Wong, & McPhee, 2010). This suggests high levels of family involvement in reducing exposure to smoking. However, in one study, 38% of Asian Americans reported being exposed to SHS at home (Ma, Tan, Fang, Toubbeh, & Shive, 2005), a finding that might be related to disparities in the enforcement of indoor smoke-free policies, particularly among lower educated Asian American women (Tong, Gildengorin, Nguyen, Tsoh, Modayil, et al., 2010).

In addition, it has been noted that family members appear to be highly involved in smoking cessation processes for Asian smokers, as was observed in a study with Asian-language callers to the California Smokers Helpline. This service provides free telephone smoking cessation counseling services in Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese, and between January 1993 and June 2008, Asian-language-speaking Asians represented the largest percentage of nonsmokers (proxies) who called to solicit help for a family member or friend (35.4% vs. 4.8% for English-speaking Whites; Zhu, Wong, Stevens, Nakashima, & Gamst, 2010). These phenomena might give insight to unique strengths of Asian American families.

Intimate relationships have long been considered a micro-social context for health-related behavior and behavior change (Huston, 2000; Schmaling & Sher, 2000); several studies have contributed to understanding the influence that intimate relationships have on behavior change and health outcomes (Lewis et al., 2006; Robles & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2003). Some researchers have advocated for interventions that address and intervene with the couple or family unit, particularly when addressing behavior change related to chronic diseases (Baucom, Porter, Kirby, & Hudepohl, 2012; Doherty & Whitehead, 1986; Rohrbaugh et al., 2001; Schmaling & Sher, 2000; Shoham, Rohrbaugh, Trost, & Muramoto, 2006).

In a review of meta-analyses conducted to explore the effectiveness of family-level interventions, Chesla (2010) reported support for the efficacy of family-level interventions over usual medical care, as well as in some cases over individual psychosocial care. While this analysis did not include studies that evaluated smoking cessation interventions, there is substantial evidence that links spousal support, and in particular the absence of spousal criticism, to smokers’ successful quit attempts (Campbell & Patterson, 1995; Coppotelli & Orleans, 1985; Gulliver, Hughes, Solomon, & Dey, 1995; Murray, Johnston, Dolce, Lee, & O’Hara, 1995; Roski, Schmid, & Lando, 1996). However, a recent Cochrane review of intervention studies focused on enhancing the support received from partners did not show a statistically significant increase in quit rates when compared with programs without this component (Park, Tudiver, & Campbell, 2012).

Park et al. (2012) postulated that the failure to find an effect may be the result of having (a) selected studies that had inadequate power to detect effects, (b) inability of interventions to effect changes in actual support provided by the partners, and (c) differences in support provided by committed partners versus relatives or other acquaintances. Other authors have argued that the effectiveness of these intervention studies has been limited due to the “one-size-fits-all strategies” that have been used to enhance social support and problem-solving skills, as well as the limitations inherent to focusing exclusively on the role of social support without considering other dynamics at play within the social context in which the smoking behaviors occur (Greaves et al., 2011; Shoham et al., 2006).

In developing a family consultation method for health-compromised smokers, Shoham et al. (2006) considered the interweaving of smoking behaviors into family and social relationships, the role that variations in relationship dynamics play in smoking behaviors and the importance of incorporating family members as full participants in the intervention and of acknowledging their stake in the outcome. Bottorff and colleagues have conducted a body of work that has explored the social context and intimate relationship dynamics surrounding tobacco use. These studies have described mothers’ experiences with reducing and quitting smoking, particularly around childbearing (Bottorff et al., 2005; Bottorff, Kalaw, et al., 2006); fathers’ experiences (Bottorff, Oliffe, Kalaw, Carey, & Mroz, 2006; Bottorff, Radsma, Kelly, & Oliffe, 2009); and children’s experiences (Bottorff, Oliffe, Kelly, Johnson, & Chan, 2013). The role that parenting styles (traditional vs. shared), gender relations, and power dynamics play in tobacco-related interactions has also been explored (Bottorff, Kelly, et al., 2010; Bottorff, Oliffe, et al., 2010; Greaves, Kalaw, & Bottorff, 2007; Oliffe, Bottorff, Johnson, Kelly, & LeBeau, 2010). Their findings clearly support the value of taking into consideration the “embedded nature” of smoking-related patterns in the home environment, as well as partner influences and social controls on individual’s smoking-related behaviors (Bottorff et al., 2005). In North America, as noted in a historical analysis conducted by White, Oliffe, and Bottorff (2012), most programmatic efforts to reduce SHS exposure in families with young children have tended to focus on reducing tobacco consumption among women. Findings from a number of studies have begun to advocate for the need for men-centered and gender-sensitive smoking cessation programs (Bottorff, Oliffe, et al., 2010; Kwon, Oliffe, Bottorff, & Kelly, 2015; Oliffe, Bottorff, & Sarbit, 2012; White et al., 2012). However, these studies have been conducted primarily among well-educated Anglo couples in Canada. No such studies have been conducted among Asian American couples. Therefore, the main objective of this study was to conduct the first in-depth exploration of family communication dynamics among Asian American families related to tobacco use. The findings and their implications for smoking cessation are presented in this report.

Method

We used qualitative methods (individual and dyadic open-ended, in-person in-depth conversational interviews) to explore family communication dynamics related to tobacco use among Vietnamese and Chinese Americans. Data analysis followed an inductive approach guided by grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). The approach was well suited to describe the types of communication, experiences, feelings, meanings, and impacts associated with tobacco use and quit attempts within families.

Data Collection

We partnered with three community-based organizations (CBOs) to conduct this study. CBO staff recruited participants from their community and professional networks for dyadic (smoker with family member) and individual (smoker, family member) interviews. Research team members and trained CBO staff conducted interviews in the language preferred by participants (e.g., Cantonese or Vietnamese). All interviews were audio-recorded. We conducted dyadic interviews first to gain insight into communication dynamics and smoking concerns within families, and to observe nonverbal communication and relationship dynamics evidenced in the interview and in a task-based exercise. The dyadic interviews started with a rapport-building discussion of participants’ background, including profession in country of origin, experiences coming to the United States, and current living situation. This led to a series of questions about smoking within the family: who smokes, how people feel about the smoking, and concerns and conflicts that arise around smoking. We probed around the smoking-related communications (concerns and conflicts) to learn about who was involved, the tone of discussions, and the results. We asked participants to talk about the last time smoking came up in family conversations and to walk us through what happened. For dyads including a current smoker, we asked both participants to reflect on previous quit attempts, rationale for trying, what worked and what did not, who was involved, where they found support (including use of smoking cessation resources) and who or what was not supportive. For dyads including a former smoker, we asked both participants to walk us through the quitting process and to discuss what they thought was most helpful in maintenance of nonsmoking status. We also asked all participants to talk about how others in their families and broader social networks viewed the smokers’ behavior and, for former smokers, how quitting changed their family and broader social relationships. Following this discussion, we asked participants to look through a brochure and watch one of several public service announcements (PSAs) about the harms of smoking. Research team members left the room while the participants read through the brochure and viewed the PSAs. After about 10 min, interviewers returned and asked participants about their reactions to the messages, their relevance to their own experience, and what questions or thoughts arose while reading or watching.

Interviewers recorded detailed field notes immediately after each interview to capture interview context, affect, and casual conversations occurring before and after the recorder was turned on. On completion, dyadic interview recordings were transcribed and translated into English by a bilingual transcriptionist, and read by research team members. Based on this reading and subsequent discussion, we developed a tailored individual interview guide for each participant in the dyadic interviews. This meant that, although the dyadic interviews covered similar topics, follow-up individual interviews focused on issues discussed within this pair’s previous dyadic interview. For example, in one dyadic interview, the wife talked about how the smell of cigarettes bothered her. In the follow-up interview, we probed around this topic and learned the profound effect her aversion to the cigarette smell was having on her relationship with her husband, from tense communications and arguments to a lack of sexual intimacy.

Data Analysis

Interview recordings from follow-up individual interviews were again translated into English and transcribed for analysis. To engage in collaborative analysis and to facilitate a crystallization process (Kiefer, 2006), we grouped transcripts together in sets (dyad and two individual interviews) for analysis. First, we distributed sets to the entire research team, and members were asked to conduct a close reading and write a reflective summary of key findings from each set, new issues discussed, recurrent themes across interviews/sets, and data relevant to intervention development. At the same time, two team members coded each transcript following a grounded theory approach (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). These team members individually coded the transcripts, and met weekly to discuss codes and emergent themes. We utilized Version 6.0 of ATLAS.ti (2010) qualitative software to organize the coding and facilitate the combined analysis. The sponsoring institutions’ human subjects review board approved all study procedures.

Demographics of the Participants

We conducted in-depth dyadic and individual qualitative interviews with 13 smokers (seven current smokers, six former smokers) and 13 family members (n = 26; see Table 1). Each member within a dyad shared the same ethnicity, with 18 Vietnamese and eight Chinese Americans in the study. Participants had lived in the United States between 3 and 38 years. While the majority were husband–wife dyads (n = 10), there was one male–female partner dyad, one mother–son dyad, and one father–son dyad. The ages of family members ranged from 23 to 60 (M = 44.1) years, and ages of smokers ranged from 19 to 65 (M = 45.7) years.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants.

| Participant role

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Smoker | Family member |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 13 | 1 |

| Female | 0 | 12 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Chinese | 4 | 4 |

| Vietnamese | 9 | 9 |

| Age (years) | ||

| M (SD) | 45.7 | 44.1 |

| Range | 19–65 | 23–60 |

| Years lived in the United States | ||

| M (SD) | 15.3 | 10.25a |

| Smoking status | ||

| Current | 7 | 0 |

| Former | 6 | 1 |

Missing data for one participant.

All current and former smokers interviewed were men. The former smokers reported smoking abstinence periods ranging from 5 months to 4 years. Except for one son, all family members interviewed were women. All but one of the family members had never smoked.

Results

Using dyadic (D)1 and individual (I)2 interviews, we identified three interrelated pathways by which smoking-related behaviors impact family interactions, closeness, and communication dynamics. The findings indicate that the shared consequences of these pathways contribute to a dynamic of avoidance and noncommunication regarding the smoking-related behavior. In addition, former smokers and their family members described the ways in which quitting smoking impacted family communication and resulted in improvements in family closeness.

Pathway 1: Smoking Directly Causes Conflicts

In the individual and dyadic interviews, both the smokers and family members described tobacco use as a direct source of conflict. The most common communication dynamic reported by both smokers and family members was that of nonsmoking family members repeatedly encouraging smokers to quit, with the smoker avoiding or refusing to engage in dialogue. Smokers’ responses to these situations ranged from doing nothing, for example, “…because if they do talk I would just smile back and let it pass [laugh]” (I), to ignoring the family member and literally leaving the room when the topic was brought upl:

I knew what she was talking about, but didn’t pay attention to it, she can say what she wants, but I have my own thing to do…when she looked at me, I would walk away…pretending that I didn’t hear. (I)

These types of smoking-related dialogues evoked a range of emotional responses from both smokers and family members. One common response was to downplay or normalize the interactions. Other smokers indicated that rather than generating empathy or appreciation, these ongoing conversations spawned irritation and anger, and even reinforced their smoking:

When I heard my wife say to reduce smoking, that you cough repeatedly, I knew that she was concerned. I was not sad…but personally, I was truly a bit irritated. Because I thought, she has already mentioned it before and I know. How come she keeps talking about it? So as the days went by, the more she said, the more I smoked [laughter]…because it irritated me, so I did it to relieve my anger. (I)

In her individual interview, this smoker’s wife corroborated his report and described the ongoing and unrelenting nature of these conversations: “I was very irritated, we quarreled every day, I complained every day, the same topics, over and over again like a broken record” (I). For some couples, the conflict was limited to verbal discussions, but others described charged physical interactions:

| Family member: | “Yes, anytime he smokes I lurk and scold him, so he has to run outside.” |

| Interviewer: | “So on hot or cold days, you [smoker] are still chased out of the house?” |

| Family member: | “Yes, if not, he cannot smoke.” |

| Interviewer: | “When you scolded him, what did he do?” |

| Family member: | “He would hold the cigarette and run around.” |

| Interviewer: | “It is good to be afraid of one’s wife.” |

| Family member: | “[He is] afraid but he still smokes” (D). |

Pathway 2: Smoking Interferes With Family Engagement

We observed that tobacco use within the smoker–family dyad directly and indirectly impacted the quality and nature of the engagement that the smoker and the family member had both with each other and their broader social network. This impact occurred on three distinct levels: (a) emotional engagement, (b) physical engagement, and (c) sexual engagement. The effects appeared to stem from family members’ perceptions of the offensiveness of the odor of cigarette smoke, knowledge of and desire to avoid the associated health risks from SHS exposure, and a decrease in the smokers’ sexual performance and/or desirability.

Emotional engagement

In individual interviews, smokers reported nonverbal behaviors used to avoid smoking-related discussions such as “ignoring” and “walking away” from the person initiating the conversation. Smokers also reported experiencing stigma and shame: “They advised me to quit. When I smoke, they look at me like they’re looking down on me” (I). Another smoker reported, “It [the smoking-related discussion] damaged my pride [and] made me feel like I was failing my wife and children” (I).

Interviews with individual family members reflected similar dynamics: “He wouldn’t look directly into [my] eyes after he came back from smoking. Seemed like he felt really guilty about it” (I). One smoker reported being looked down on, and when asked whether he felt this way both inside and outside the house, he responded, “Either way, since [my] neighborhood is American.” Thus, the social unacceptability and smoking norms (denormalization) experienced in both home and neighborhood led to perceived stigmatization among those who smoke. Smokers and family members alluded to experiencing changes in individual and broader social norms around the acceptability of smoking in the United States and, in particular, public smoking norms and policies as compared with Vietnam or China. It was primarily male current smokers who reported being impacted by these differences; however, several wives also acknowledged that, prior to immigrating to the United States, they had not spoken up about their spouses’ smoking as often as they did now.

Smoking-related conflicts negatively impacted the overall emotional climate of the home. One smoker reported that his smoking and the smoking-related discussions undermined his authority with his children and generated passive-aggressive responses from them:

When I told them to do something, they reacted angrily. They did not want to do what I asked, even though they would do those things 15 or 20 minutes later. When they washed the dishes, they would make noises. I could sense their reaction. (I)

His struggle to know how to respond was compounded by the differences in cultural contexts between Vietnam and the United States:

With regards to smoking, they avoided talking to me. If we were in the same room, I might look at them but would not talk to them. I would want to make up with them, but I felt I had too much pride. I felt that not everything I did was right. In Vietnam, the father has the most authority, but [here] I thought that was wrong. (I)

Family members reported that over time, these conflict-ridden dynamics impacted their feelings toward the smoker: “Although I love him, my love diminishes because this is a problem that affects our relationship” (I). Smokers also acknowledged that the conflicts lingered for extended periods of time and affected the family’s emotional well-being: “After the complaints, we felt angry. It might last a few days, or even a week. Then we would make up, but we were not as happy as before” (I).

Physical engagement

In individual interviews, smokers reported that consideration for family members’ health and comfort led to their distancing, isolating, or separating themselves from other family members. One smoker said, “…I only speak to [others] through my wife, then my wife conveys my thoughts to them…or standing far from them on the outside of the house, they feel more ventilated.” He maintained this distancing at home: “I dine separately. For example, 7 PM is dinner time; I stay inside and avoid them, making me less worried” (I). In a dyadic interview, one smoker stated,

My brother had been in the U.S. for a long time, his children also. They all felt uncomfortable with the smoking smell and informed me frequently…I said, “O.K., let me smoke outside.” However, going outside, I felt strange. Just me, myself alone on the road, I thought it looked weird. (D)

Family members in individual interviews confirmed this behavior and expressed distress over their smoker’s frequent absences:

Like in a party or dinner at a restaurant, everyone is happy, then suddenly I saw that my father had the craving, he suddenly went out. I felt a little sad because everyone was happy and talking but he ran out…It was not like he was angry with me, he went out just because he craved a cigarette and ran out to smoke, so I was sad. (I)

Family members reported feeling that they were expected to physically distance themselves from smokers. The wife of a former smoker described this experience as one of being shunned, stating, “When he was still smoking, he told us to go to the other corner to sit, just like a leper” (I).

Sexual intimacy

Wives and partners of smokers sometimes voiced direct concern about the impact that smoking was having on their sexual relationships. This was communicated exclusively during the individual interviews; the topic was never discussed in dyadic interviews. Several wives reported that this was not something they had discussed with their husbands out of fear that “the relationship would be harmed” (I). However, it clearly weighed heavily on them:

I had this sense and I thought other women had it too, but they did not speak their mind because they felt ashamed. I was very upset but did not know how to tell him [that smoking]…affects the sexual activities of husbands and wives. (I)

Wives also observed decreases in their husbands’ sexual performance, including lessening sexual arousal and difficulties with exertion (“the breath”). According to this same wife, these side effects decreased the smoker’s own “enthusiasm,” which in turn impacted both partners’ interest in sexual intimacy: “…if his diminishes, mine diminishes too” (I). In addition, wives reported sensitivity to and repulsion of the odors associated with smoking. One participant said,

I am very sensitive especially to his sweat mixed with cigarette smoke. It is unbearable. Women of my age still have a sexual appetite…but this bad odor makes us lose our sexual appetite.…I wanted him to kiss me, but this odor made me uncomfortable. (I)

While none of the smokers discussed sexuality directly, they did report awareness of their spouse’s sensitivities to the odors associated with smoking and reported a range of approaches to eliminate the odor and/or hide smoking activities from family members. As one smoker explained, “Before coming home for dinner, I would wait half an hour until the smell was less strong; then I would go home, wash my face, rinse my mouth. I tried not to let her smell it” (I).

Pathway 3: Smoking Disrupts Family Harmony

Family members voiced concern about the impact that tobacco use had on family “harmony.” These comments were made during the individual, not dyadic, interviews and were most commonly expressed in terms of worry over how smoking-related conflict interfered with family engagement, and disrupted the family “atmosphere” or “mood.” In addition, many family members described struggling to find a balance between addressing health-related concerns, enduring the potential conflicts that arose from addressing the smoking behavior and desiring to promote and maintain a harmonious atmosphere in the home. One family member described this dilemma:

I knew…if I were to continue nagging him, he would give me an unhappy look. I don’t want to keep discussing an issue that can never get resolved; I don’t want to ruin the atmosphere within the family.…I’m not happy when the atmosphere in the family is so intense [laugh], that’s how I feel.…Smoking likely doesn’t create as big an impact in comparison to the effect of ruining one’s mood…so that’s why I don’t want to create any more arguments. (I)

Many family members (particularly mothers and their children) reported prioritizing “keeping the peace” over confronting a spouse and/or parent over smoking. Others acknowledged compromising. One mother reported advocating to protect herself and her child from SHS exposure, yet also admitted that there were times when she refrained from discussing her husband’s smoking to avoid conflict and maintain peace in the home:

I told him to try to reduce it if possible, but if you still smoke, then get out of the house to smoke. Any time my husband smoked, he went to the living room, but the smoke…I did not know how, but it got into the bedroom. The smell was so strong. I was very irritated. I told him to go far away to smoke, don’t do it in the house. “[When] you smoke, then my daughter and I will get sicker.” I felt that my husband was not happy, so sometimes I refrained. I thought, we have a child in the house—sometimes I did not want to raise my voice to him. (I)

Family members struggled to understand their husband or parent’s smoking-related actions. Wives were empathetic with their husbands, yet continued to experience distress over how to address the health concerns and interpersonal conflicts associated with smoking. For example, one wife shared that it felt like her husband was choosing smoking over his family: “I think he needed that [smoking cigarettes] more than me and my daughter” (I). She appeared to be both saddened and mystified by his lack of regard for his own health and appreciation for her concerns: “So if he does not take care of his own health, he will have to live with that…[however] I am also devoted. I wanted to safeguard his health but he disregarded my words” (I).

In addition, some wives expressed their concern that the smoker was not living up to their expectations for his role, and that he was setting a bad example for their children and other family members: “You are the head of the family, the lead person in the family, you should serve as an example for me and our daughter” (I).

In both individual and dyadic interviews, smokers made comments that acknowledged their awareness of the toll that their smoking was having on ordinary family dynamics, though they did not describe it in terms of how it was directly impacting or interrupting the family’s harmony. For example, a current smoker verbalized distress and frustration with the everyday standoff his smoking was creating between him and his children:

They said that when I passed their room, they could smell the smoking and could not stand it. They asked me not to stand next to their room. That’s what influences me [to quit]. Being a father and not having my children talk to me, and myself not being able to talk to them, I feel so frustrated. (D)

Shared Consequences of the Three Interrelated Pathways

With time, family members felt that their smoking-related conversations had become futile: “It just passed from one ear to another. He did not say anything, he still continued smoking” (I), as well as polarizing: “How does he think? I don’t know how he thinks, like I told you before, this is a really sensitive topic” (I). Another wife said,

[M]any times I thought maybe me and my daughter could partition the house in half, to separate him. But it would not work because we are a family. We can ignore him, that is okay, but then I pity him. I told him, I was thinking about the family’s health, that’s why I reminded him, otherwise I didn’t care to remind him.…I thought I told him with a good intention, why didn’t he listen to me? But instead he just irritated me more. (I)

Family participants recalled times when they were intently engaged in discussing this issue with their husband or father, after which they became resigned to the fact that he was not going to change, or that he would change only when ready. A number of family members reported feeling powerless and helpless:

Let it be. If he smokes too much, he will harm himself. Not only does he harm himself but he also harms people around him, especially me…I cannot remind him every day. (D)

I feel that, why would you still want to treat yourself like that knowing how it would harm your health? I feel helpless and like there is nothing I can do. Talking about it is something that I did in the past but I have since given up. (I)

Some smokers acknowledged that their spouses had backed off as their smoking continued: “My wife wouldn’t talk to me about that any more because she has been talking about it for so many years [laugh]…I still haven’t changed much, so she stopped talking to me much about it” (I).

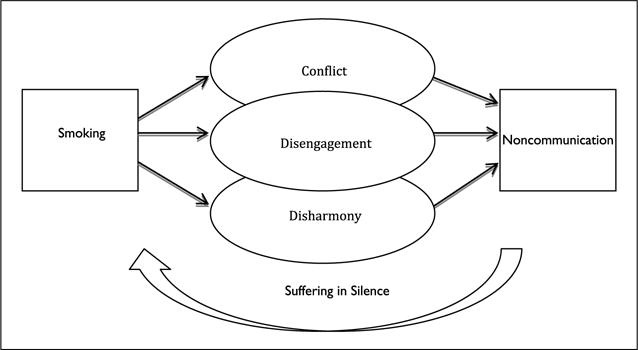

Over time, couples appeared to reach an impasse where they compromised to move forward. Family members refrained from engaging the smoker in smoking-related dialogues because of the futility they had experienced in the past. They appeared to avoid the topic in an attempt to minimize conflict and restore or maintain harmony within the family. Yet, the smokers’ smoking-related behavior remained an ongoing source of conflict, disengagement, and disharmony for the family unit. While the actual conflict might wax and wane, the smoker’s tobacco use continued to be a source of irritation, frustration, and/or exasperation for smokers and family members. The resulting noncommunicative dynamic contributes to all involved essentially “suffering in silence” with each family member dealing with the frustration on their own and in their own way. Furthermore, this dynamic might indirectly enable and/or reinforce the continuance of smoking—with smokers stating that they “smoked more” to deal with the frustration—ultimately resulting in a vicious cycle of continued smoking, conflict, disengagement, and disharmony (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The smoking and noncommunication cycle.

Note. Tobacco use impacts family communication dynamics through three interrelated pathways. The shared consequences of these pathways contribute to a dynamic of avoidance and noncommunication in relation to the smoking behavior. This dynamic has the potential to contribute to the continuance of smoking, ultimately creating a vicious cycle of continued smoking, conflict, disengagement, and disharmony with the individual smoker and family members each “suffering in silence.”

Impacts and Benefits of Quitting on Family Communication Dynamics

Former smokers described the impacts and benefits that quitting had on their interpersonal relationships. Their experiences suggested that the consequences of smoking on family conflict, disengagement, and disharmony could be undone and/or reversed. These impacts included greater attentiveness from their partners (“After I quit, my wife took care of me more” [I]), fewer conflicts (“Now that I quit smoking, there is less conflict between [us]” [I]), and greater respect from family members (“They respected me a little more” [I]). These changes represent potential shifts in the smokers’ sense of engagement and connection with family members.

Quitting smoking also created dramatic changes in family members’ level of physical engagement with one another. The same wife, who had reported feeling like a “leper” as a result of the expectation that she and her children distance themselves from her husband while he smoked, reported,

Oh god, wonderful! When he quit, she (my daughter) kissed her dad, no smell…After he quit, the family—husband and wife and child are very happy [laughter], sitting next to each other to tell jokes, eating without any smell. (I)

Discussion

Utilizing dyadic and individual interviews of smoker–family pairs, we identified three interrelated pathways by which tobacco use within immigrant Vietnamese and Chinese families impacts family processes and communication dynamics. First, smoking represents a direct source of conflict for these families. The nature, quality, tone, and results of these conflicts are described and provide important insights into the daily-lived experiences of smokers and their family members. Second, smoking-related behaviors interfere both directly and indirectly with the family’s emotional and physical engagement as well as the couple’s sexual intimacy. Third, smoking-related behaviors lead to disruptions in the family’s perceived level of harmony. Ultimately, the shared consequences of these interrelated pathways contribute to a dynamic of avoidance and noncommunication resulting in a vicious cycle of conflict, disengagement, disharmony, and the continuance of smoking. The experiences of successful quit attempts shared by former smokers and their family members illustrate one way to exit the smoking–noncommunication cycle. Quitting has the potential to reverse the negative consequences of smoking-related behaviors on family dynamics and increase understanding, engagement, and harmony within the family. These findings enhance understanding of the impact tobacco use can have on family communication dynamics within Asian American families and have the potential to inform future studies and interventions.

Methodologically, this study demonstrates the value of combining dyadic and individual interviews, which revealed the discordance of the information gathered in the two types of interviews. Participants discussed the frequency and nature of conflicts that tobacco use generated and the impact it had on the family’s level of physical engagement with one another in both the individual and dyadic interviews. However, discussions related to the impact that continued smoking and failed quit attempts had on the family’s level of emotional engagement, family harmony, and the couple’s sexual intimacy occurred only during the individual interviews, and such themes were offered only by the family members. The individual interviews allowed the family members, who were mostly women, to speak out in private. The willingness to do so might have been enhanced by the family members’ ability to express their commitment to family harmony during the earlier dyadic interview. It might also have helped to save the family’s “face” or reputation in front of the interviewers, which has been acknowledged as an important priority for Asian Americans (Ho, 1976; Triandis, 1995).

Harmony tends to be an important cultural value among Asian Americans (Triandis, 1995; Wei, Su, Carrera, Lin, & Yi, 2013). The emphasis on family harmony that emerged in this study illuminates the dilemmas that tobacco use creates for Vietnamese and Chinese immigrant families. Family members described having deeply held concerns for the smoker’s health, as well as that of the other members of the household. However, participants reported that addressing smoking also generated challenges to the family’s peace and harmony because of the heated and difficult nature of smoking-related communications. Our findings illustrate how, for the benefit of their children and the family unit, family members struggled to avoid conflicts, reduce disengagements, and restore or maintain harmony within the family by ceasing to address tobacco use in the family, while attempting to address health concerns. At times, maintenance of the family’s peace prevailed over prioritizing physical health, especially in families that seemed to have reached an impasse concerning this issue.

These findings help to expand understanding of couple interactions, as well as individual men and women’s experiences within the context of male smoking. They also provide further insight into the complex interplay between cultural norms, sex, and gender roles in regard to tobacco use within the family unit. Bottorff, Oliffe, et al. (2010) found that women’s experiences of being both “defender” and “regulator of men’s smoking” can be heavily influenced by emphasized femininities and traditional masculinities (p. 583). Both male and female participants in this study described ways in which smoking impacted male smokers’ identities as husbands and fathers. The findings also suggest that interaction patterns can change over time and might be influenced by other contextual factors at play within the couple relationship such as changes in external discourses regarding the social denormalization of smoking and SHS, immigration status, employment, and living situation.

Finally, the findings from this study have implications for intervention development. First, interventions to address smoking cessation in these populations need to take into account the social and cultural contexts of the smoker, including gender relations, and promote the importance of including family members in the smoking cessation process. Second, interventions should educate both smokers and their families not only about the benefits of smoking cessation on individual and family health but also about the non-health-related benefits of quitting, specifically emphasizing the benefits of decreasing smoking-related conflicts, increasing family closeness or engagement, and restoring and maintaining family harmony. Finally, interventions are needed to help both smokers and their families end the individual “silent suffering” by helping them to break out of the pattern of noncommunication and interrupt the vicious cycle shown in Figure 1.

While the current state of smoking cessation research has yet to demonstrate effective ways of enhancing partner support that yields sustainable smoking cessation outcomes (Park et al., 2012), our findings speak to the need to continue to enhance our understanding of how smoking-related behaviors influence family communication dynamics within the context of particular cultural groups. In Asian American families, the way that these influences are perceived and valued might have the potential to shape individuals’ and families’ experiences with smoking cessation interventions. The findings in this study underscore the importance of breaking the pattern of noncommunication between smokers and their family members.

These findings were used to inform the development of a social network family-focused intervention, which aimed to provide a socially acceptable opportunity for smokers and their family members to discuss tobacco-related concerns in the context of promoting both family health and harmony. In the newly developed intervention, lay health workers served as peer educators and conducted outreach activities that involved gatherings of smokers and their family members with other smokers and family members in a small group with the goal of putting the topic of smoking cessation back on the table for discussion in a nonthreatening and socially supportive way. The pilot study findings indicate that the intervention was highly acceptable to both smokers and their family members (94% of smokers and 98% of family members would recommend the program to others). In addition, the program effectiveness was supported by a promising 30-day smoking abstinence rate (24%; Tsoh et al., 2015). A randomized controlled trial is currently being conducted to test its efficacy.

Limitations

This study had a number of limitations. Because the aim of this phase of the study was to identify opportunities for family members to support smoker’s cessation efforts, the focus of the interviews was primarily on challenges related to tobacco use versus benefits of quitting and participant’s experiences with reducing and quitting cigarette use. This approach might have limited the types of tobacco-related interaction patterns observed. The sample had more Vietnamese (75%) than Chinese (25%), which limited the ability to analyze the data for differences between these two ethnic groups. It should also be noted that Chinese American participants were all Cantonese speaking who were immigrants from Southern China (one from Hong Kong and seven from Guandong province); this along with the small sample size of the Chinese participants further limits the transferability of the findings. The views shared by these participants may not represent those of smokers and nonsmoking family members from other parts of China where smoking prevalence and smoke-free policies may greatly differ. Finally, the sample was comprised of only male smokers, and primarily of husband and wife couples (only one father–son dyad and one son–mother dyad), which limited the ability to fully explore the perspectives and experience of female smokers, as well as other types of family members.

Conclusion

Dyadic and individual interviews of Asian American smokers and their family members revealed the complex interactions between culture, immigration, and health present in smoking-related communication within the family context. These findings contribute to our understanding of the role that the micro-social context of the home might have on smoking-related behaviors, and in particular on smoking cessation. Families in our study worked to manage family conflict while juggling competing demands and values, such as maintenance of family harmony versus avoidance of SHS exposure. This is difficult for any family but might be especially difficult for Asian families where conflict tends to be avoided and harmony prioritized (Triandis, 1995). More research is needed to explore how cultural and family contextual issues influence smoking-related communication and behaviors, and to incorporate such concerns into innovative approaches that will effectively support smokers and their family members throughout the quitting process.

Acknowledgments

We want to express gratitude to Ching Wong and Khanh Le of the University of California, San Francisco Suc Khoe La Vang! (Health Is Gold!) Project for their essential contributions to the study; Joyce W. Cheng and staff of the Chinese Community Health Resources Center (CCHRC), and Anthony N. Nguyen and staff at the South East Asian Community Center (SEACC) and the Vietnamese Voluntary Foundation (VIVO) for their assistance and support in participant recruitment, as well as for conducting and transcribing interviews; and to Icarus Tsang for his contribution to data coding and analysis.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Research is supported by grants from the Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (19XT-0083H, 22RT-0089H), National Institute on Drug Abuse (R21DA030569, P50DA03569, R01DA036749), and the National Cancer Institute (K07CA126999). Additional support was provided by the Asian American Network for Cancer Awareness, Research, and Training (AANCART) National Center, funded by the National Cancer Institute through Grant U54 CA153499 and the Asian American Research Center on Health (ARCH).

Biographies

Anne Berit Petersen, PhD, MPH, RN, was a doctoral candidate in the School of Nursing at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), when this article was written. She is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the UCSF Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education and an assistant professor at Loma Linda University School of Nursing, California, United States. Her research interests include global health promotion, tobacco-dependence treatment, and promotion of smoke-free homes. Her recent publications include “E-Cigarette Marketing and Older Smokers: Road to Renormalization” in American Journal of Health Behavior (2015, with J. Cataldo, M. Hunter, J. Wang, & N. Shoen), “Positive and Instructive Anti-Smoking Messages Speak to Older Smokers: A Focus Group Study” in Tobacco Induced Diseases (2015, with J. K. Cataldo, M. Hunter, & N. Shoen), and “Factors That Influence Diabetes Self-Management in Hispanics Living in Low Socioeconomic Neighborhoods in San Bernardino, California” in Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health (2012, with E. Ramal, K. Ingram, & A. Champlin).

Janice Y. Tsoh, PhD, is an associate professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the UCSF, California, United States. Her research program focuses on reducing cancer health disparities, particularly in designing culturally sensitive interventions in promoting smoking cessation and cancer prevention screening targeting non-English-speaking populations in community and practice-based settings. Her recent publications include “Individual and Family Factors Associated With Intention to Quit Among Male Vietnamese American Smokers: Implications for Intervention Development” in Addictive Behaviors (2011, with E. K. Tong, G. Gildengorin, T. T. Nguyen, M. V. Modayil, C. Wong, & S. J. McPhee) and “A Social Network Family-Focused Intervention to Promote Smoking Cessation in Chinese and Vietnamese American Male Smokers: A Feasibility Study” in Nicotine & Tobacco Research (2015, with N. J. Burke, G. Gildengorin, C. Wong, K. Le, A. Nguyen, J. L. Chan, A. Sun, S. J. McPhee, & T. T. Nguyen).

Tung T. Nguyen, MD, is a professor of medicine and the Stephen J. McPhee Endowed Chair in General Internal Medicine at the UCSF, California, United States. His research interests are community-based participatory research and health disparities research, with a focus on cancer control and prevention, including tobacco control. His recent publications include “Smoking Prevalence and Factors Associated With Smoking Status Among Vietnamese in California” in Nicotine & Tobacco Research (2010, with E. K. Tong, G. Gildengorin, J. Tsoh, M. V. Modayil, C. Wong, & S. J. McPhee) and “Individual and Family Factors Associated With Intention to Quit Among Male Vietnamese American Smokers: Implications for Intervention Development” in Addictive Behavior (2011, with J. Y. Tsoh, E. K. Tong, G. Gildengorin, M. V. Modayil, C. Wong, & S. J. McPhee).

Stephen J. McPhee, MD, is a professor of medicine, Emeritus in the Division of General Internal Medicine in the Department of Medicine at the UCSF, California, United states. His research interests include general internal medicine, preventive medicine, and palliative care. His recent publications include “Effectiveness of Lay Health Worker Outreach to Reduce Disparities in Colorectal Cancer Screening in Vietnamese Americans” in American Journal of Public Health (2015, with B. H. Nguyen, S. L. Stewart, T. T. Nguyen, N., & Bui-Tong), “Cognitive Interviews of Vietnamese Americans on Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Health Educational Materials” in Ecology of Food Nutrition (2015, with B. H. Nguyen, C. P. Nguyen, S. L. Stewart, N. Bui-Tong, & T. T. Nguyen), and “A Social Network Family-Focused Intervention to Promote Smoking Cessation in Chinese and Vietnamese Male Smokers: A Mixed Methods Feasibility Study” in Nicotine & Tobacco Research (2015, with J. Y. Tsoh, N. J. Burke, C. Wong, K. Le, G. Gildengorin, A. Nguyen, J. L. Chan, A. Sun, & T. T. Nguyen).

Nancy J. Burke, PhD, was an associate professor of medical anthropology in the Department of Anthropology, History, and Social Medicine at the UCSF, California, United States, when this article was written. She maintains this affiliation and has also become associate professor in the School of Social Sciences, Humanities, and Arts at the University of California, Merced. She has conducted research in Cuba and the United States on social and cultural processes associated with chronic disease management and cancer prevention, treatment, and survivorship. Her recent publications include “Protecting Our Khmer Daughters: Ghosts of the Past, Uncertain Futures, and the HPV Vaccine” in Ethnicity and Health (2014, with H. H. Do, T. Talbot, C. Sos, S. Ros, & V. M. Taylor), “Developing Theoretically Based and Culturally Appropriate Interventions to Promote Hepatitis B Testing in 4 Asian American Populations, 2006–2011” in Preventing Chronic Disease (2014, with A. E. Maxwell, R. Bastani, B. A. Glenn, V. M. Taylor, T. T. Nguyen, S. L. Stewart, & M. S. Chen), and “Pakikisama: Lessons Learned in Partnership Building With Filipinas With Breast Cancer for Culturally Meaningful Support” in Global Health Promotion (2014, with O. Villero & I. Macaerag).

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not reflect the official views of the funders.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Dyadic (smoker and family member) interview.

Individual (smoker or family member) interview.

References

- An N, Cochran SD, Mays VM, McCarthy WJ. Influence of American acculturation on cigarette smoking behaviors among Asian American subpopulations in California. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10:579–587. doi: 10.1080/14622200801979126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ATLAS.ti. ATLAS.ti (Version 6.0) [Computer Software] Berlin, Germany: Scientific Software Development; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Baucom D, Porter L, Kirby J, Hudepohl J. Couple-based interventions for medical problems. Behavior Therapy. 2012;43:61–76. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottorff JL, Kalaw C, Johnson J, Chambers N, Stewart M, Greaves L, Kelly M. Unraveling smoking ties: How tobacco use is embedded in couple interactions. Research in Nursing & Health. 2005;28:316–328. doi: 10.1002/nur.20085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottorff JL, Kalaw C, Johnson JL, Stewart M, Greaves L, Carey J. Couple dynamics during women’s tobacco reduction in pregnancy and postpartum. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2006;8:499–509. doi: 10.1080/14622200600789551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottorff JL, Kelly MT, Oliffe JL, Johnson JL, Greaves L, Chan A. Tobacco use patterns in traditional and shared parenting families: A gender perspective. BMC Public Health. 2010;10 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-239. Article 239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottorff JL, Oliffe JL, Kalaw C, Carey J, Mroz L. Men’s constructions of smoking in the context of women’s tobacco reduction during pregnancy and the postpartum. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62:3096–3108. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottorff JL, Oliffe JL, Kelly MT, Greaves L, Johnson JL, Ponic P, Chan A. Men’s business, women’s work: Gender influences and fathers’ smoking. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2010;32:583–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottorff JL, Oliffe JL, Kelly MT, Johnson JL, Chan A. Reconciling parenting and smoking in the context of child development. Qualitative Health Research. 2013;23:1042–1053. doi: 10.1177/1049732313494118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottorff JL, Radsma J, Kelly M, Oliffe J. Father’s narratives of reducing and quitting smoking. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2009;31:185–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2008.01126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Health Interview Survey. CHIS 2011–2012 (Adult Public Use File) Los Angeles: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2013. Retrieved from http://ask.chis.ucla.edu. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell TL, Patterson JM. The effectiveness of family interventions in the treatment of physical illness. Journal of Marital & Family Therapy. 1995;21:545–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.1995.tb00178.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health effects of secondhand smoke. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/secondhand_smoke/health_effects. [Google Scholar]

- Chae D, Gavin A, Takeuchi D. Smoking prevalence among Asian Americans: Findings from the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS) Public Health Reports. 2006;121:755–763. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100616. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1781917/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesla C. Do family interventions improve health? Journal of Family Nursing. 2010;16:355–377. doi: 10.1177/1074840710383145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Rankin S, Stewart A, Oka R. Effects of acculturation on smoking behavior in Asian Americans. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2008;23:67–73. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000305057.96247.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppotelli HC, Orleans CT. Partner support and other determinants of smoking cessation maintenance among women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:455–460. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.53.4.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty W, Whitehead D. The social dynamics of cigarette smoking: A family systems perspective. Family Process. 1986;25:453–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1986.00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B, Strauss A. Discovery of Grounded Theory. Chicago, IL: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman BK, Lariscy JT, Kaushik C. Gender, acculturation, and smoking behavior among U.S. Asian and Latino immigrants. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;106:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves L, Kalaw MA, Bottorff JL. Case studies in power and control related to tobacco use during pregnancy. Women’s Health Issues. 2007;17:325–332. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves L, Poole N, Okoli CTC, Hemsing N, Qu A, Bialystok L, O’Leary R. Expecting to quit: A best practices review of smoking cessation interventions for pregnant and postpartum girls and women. 2nd. Vancouver, Canada: British Columbia Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health; 2011. Retrieved from http://www.expectingtoquit.ca/documents/expecting-to-quit-singlepages.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gulliver S, Hughes J, Solomon L, Dey A. An investigation of self-efficacy, partner support and daily stresses as predictors of relapse to smoking in self-quitters. Addiction. 1995;90:767–772. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.9067673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho DY. On the concept of face. American Journal of Sociology. 1976;81:867–884. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2777600. [Google Scholar]

- Huston T. The social ecology of marriage and other intimate unions. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62:298–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00298.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A, Agaku IT, O’Connor E, King BA, Kenemer JB, Neff L. Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2005–2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2014;63:1108–1112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer CW. Doing health anthropology: Research methods for community assessment and change. 1st. New York, NY: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Ziedonis D, Chen K. Tobacco use and dependence in Asian Americans: A review of the literature. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9:169–184. doi: 10.1080/14622200601080323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon JY, Oliffe JL, Bottorff JL, Kelly MT. Masculinity and fatherhood: New fathers’ perceptions of their female partners’ efforts to assist them to reduce or quit smoking. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2015;9:332–339. doi: 10.1177/1557988314545627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, McBride C, Pollak K, Puleo E, Butterfield R, Emmons K. Understanding health behavior change among couples: An interdependence and communal coping approach. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62:1369–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Kwon SC, Weerasingh I, Rey MJ, Trinh-Shevrin C. Smoking among Asian Americans: Acculturation and gender in the context of tobacco control policies in New York City. Health Promotion Practice. 2013;14(5 Suppl):18S–28S. doi: 10.1177/1524839913485757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma GX, Tan Y, Fang CY, Toubbeh JI, Shive SE. Knowledge, attitudes and behavior regarding secondhand smoke among Asian Americans. Preventive Medicine. 2005;41:446–453. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills A, White M, Pierce J, Messer K. Home smoking bans among U.S. households with children and smokers: Opportunities for intervention. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;41:559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray RP, Johnston JJ, Dolce JJ, Lee WW, O’Hara P. Social support for smoking cessation and abstinence: The Lung Health Study. Addictive Behaviors. 1995;20:159–170. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(99)80001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe JL, Bottorff JL, Johnson JL, Kelly MT, LeBeau K. Fathers: Locating smoking and masculinity in the post-partum. Qualitative Health Research. 2010;20:330–339. doi: 10.1177/1049732309358326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe JL, Bottorff JL, Sarbit G. Supporting fathers’ efforts to be smoke-free: Program principles. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research. 2012;44(3):64–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park EW, Tudiver FG, Campbell T. Enhancing partner support to improve smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;7 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002928.pub3. Article CD002928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles T, Kiecolt-Glaser J. The physiology of marriage: Pathways to health. Physiology & Behavior. 2003;79:409–416. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(03)00160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrbaugh M, Shoham V, Trost S, Muramoto M, Cate R, Leishow S. Couple dynamics of change-resistant smoking: Toward a family consultation model. Family Process. 2001;40:15–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2001.4010100015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roski J, Schmid LA, Lando HA. Long-term associations of helpful and harmful spousal behaviors with smoking cessation. Addictive Behaviors. 1996;21:173–185. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmaling K, Sher TG. The psychology of couples and illness: Theory, research and practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Shoham V, Rohrbaugh MJ, Trost SE, Muramoto M. A family consultation intervention for health-compromised smokers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;31:395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Shimizu R, Chen MS. English language proficiency and smoking prevalence among California’s Asian Americans. Cancer. 2005;104(S12):2982–2988. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong EK, Gildengorin G, Nguyen T, Tsoh J, Modayil M, Wong C, McPhee SJ. Smoking prevalence and factors associated with smoking status among Vietnamese in California. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12:613–621. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong EK, Gildengorin G, Nguyen T, Tsoh J, Wong C, McPhee S. California Vietnamese Adult Tobacco Use Survey: Executive summary. 2010 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq056. Retrieved from http://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/tobacco/Documents/Archived%20Files/CTCPVietnameseSurvey.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tong EK, Nguyen T, Vittinghoff E, Perez-Stable E. Smoking behaviors among immigrant Asian Americans rules for smoke-free homes. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;35:64–67. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong EK, Tang H, Tsoh J, Wong C, Chen M. Smoke-free policies among Asian-American women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;37(2 Suppl):S144–S150. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC. Individualism and collectivism. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tsoh JY, Burke NJ, Gildengorin G, Wong C, Le K, Nguyen A, …Nguyen TT. A social network family-focused intervention to promote smoking cessation in Chinese and Vietnamese American male smokers: A feasibility study. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2015;17:1029–1038. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei M, Su JC, Carrera S, Lin S, Yi F. Suppression and interpersonal harmony: A cross-cultural comparison between Chinese and European Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2013;60:625–633. doi: 10.1037/a0033413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White C, Oliffe JL, Bottorff JL. Fatherhood, smoking, and secondhand smoke in North America: An historical analysis with a view to contemporary practice. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2012;6:146–155. doi: 10.1177/1557988311425852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Tobacco: Fact sheet no. 339. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs339/en/#.

- Zhang J, Wang Z. Factors associated with smoking in Asian American adults: A systematic review. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10:791–801. doi: 10.1080/11462220082027230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu SH, Wong S, Stevens C, Nakashima D, Gamst A. Use of a smokers’ quitline by Asian language speakers: Results from 15 years of operation in California. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:846–852. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]