Abstract

Korea has the highest suicide rate amongst the OECD countries. Yet, its research on suicidal behaviors has been primitive. While the Interpersonal Psychological Theory of Suicide has gained global attention, there has only been a few researches, which examined its applicability in Korea. In this article, we review the previous studies on suicide and examine the association between the Interpersonal Psychological Theory of Suicide and traditional Korean culture, with an emphasis on Collectivism and Confucianism. We propose that pathways to suicide might vary depending on cultural influences. Clinical implications and suggestions for future research will be discussed.

Keywords: Interpersonal psychological theory of suicide, Thwarted belongingness, Perceived burdensomeness, Acquired capability, Collectivism, Confucianism

INTRODUCTION

Suicide is a leading cause of death, which affects millions worldwide.1,2,3 However, research on the detrimental phenomenon has been restricted for various reasons, including that there has been no comprehensive theory that encompass results from previous studies and suggest directions for future research.4,5 Recently, Joiner's Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (IPTS) has been gaining increased empirical support, suggesting it as a possible solution to the previously mentioned limitation of suicide research.5,6,7,8,9

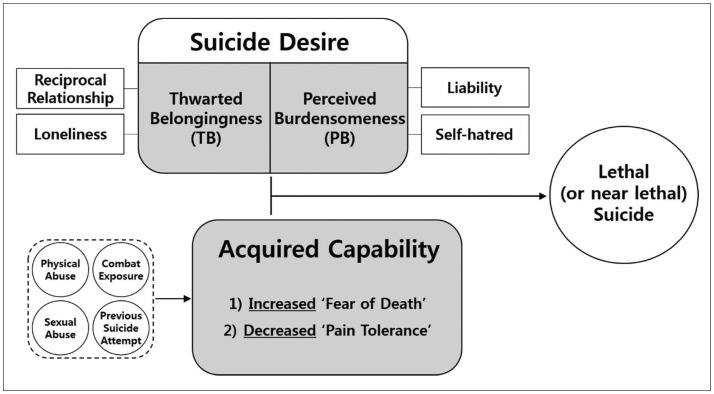

According to the IPTS, death by suicide occurs only when an individual develops the desire to commit suicide and the ability to put it into action.5,7 The desire to commit suicide is composed of two affect laden cognitions: thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness.5,7 Thwarted belongingness is a state in which an individual's ‘need to belong’ is hindered; it is comprised of the feeling of loneliness and the lack of sufficient reciprocal relationships. Perceived burdensomeness, on the other hand, is a cognitive state in which individuals believe themselves to be a liability towards significant others; it is consisted of the cognition that one is a burden and the negative affect of self-hatred. While the experience of a single component is thought to predict passive suicide ideation (i.e., ‘It would be better if I were dead’), the concurrent experience of both components, tagged with the thought that they are stable and unchanging (i.e., hopelessness), is believed to predict active suicide ideation (i.e., ‘I want to kill myself’) (Figure 1).5,7,9

Figure 1. The Interpersonal Psychological Theory of Suicide (IPTS). The shaded items indicate the core constructs of the IPTS.

However, the progression from an active suicide ideation to a death by suicide depends on the presence of a third component: acquired capability.5,7,9 Self-preservation is such a robust natural instinct that only a few can willingly withdraw it. In order to overcome this basic human nature, individuals must acquire the capability to commit suicide. The IPTS posits that constant exposure to provocative or painful events (i.e., physical abuse, sexual abuse, combat exposure, previous suicide attempt etc.) habituates individuals towards pain.5 Through this continuous process, individuals develop an elevated tolerance towards pain and a decreased fear of death, which ultimately enable them to utilize more lethal measures when attempting suicide (Figure 1).10

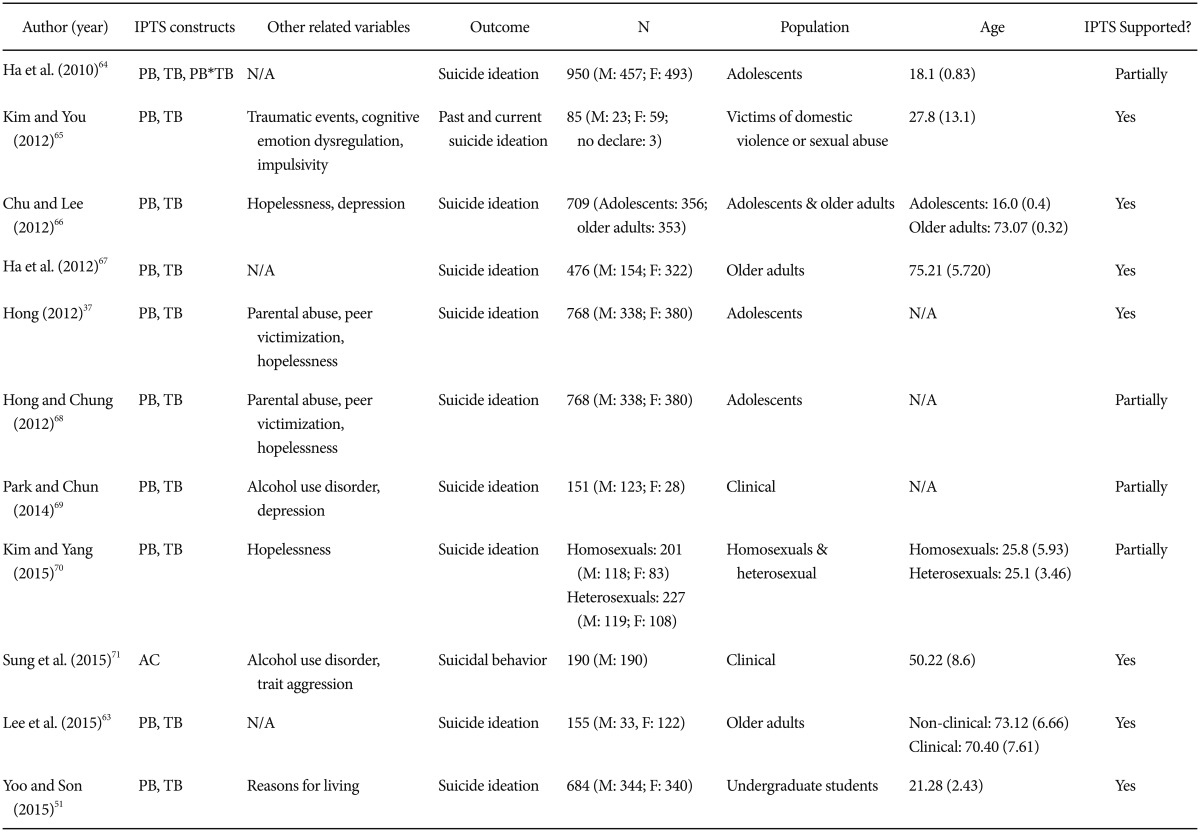

IPTS has provided apt explanations to unresolved discrepancy between the prevalence of suicide ideation and suicide attempt; ideation is possible when two constructs (i.e., thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness) are present, whereas, all three constructs have to be present in order to attempt suicide (Figure 1). The theory has also provided profound insight and accelerated research in suicidal behaviors.9 Its constructs have demonstrated stronger predictive power than some of the most warranted variables that have previously been associated with suicide, such as depression, hopelessness and social support.11,12,13 Various studies have confirmed its significance across multiple ages, clinical samples, combat veterans and even specific populations such as prison inmates.14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23 Yet, motives for suicide often vary by culture, and for a theory to be truly comprehensive it should not only be applicable to all ages and clinical symptoms, but also to different ethnicities and cultural influences.24 Minimal effort has been made to examine the usefulness of the IPTS in various cultures8 and only a handful of studies have tested it in Korea (Table 1). We believe that the IPTS successfully portrays much of the cultural and social influences that prevails in Korea and that the theory will enhance our understanding of suicide in the nation. In this article, we will review some of the previous literature that has applied the IPTS in Korea and discuss its clinical implications and directions for future research.

Table 1. Peer-reviewed Korean researches on the IPTS (N=11).

Dissertations have been excluded. Papers have been searched through DBpia on Sep. 1st, 2016. IPTS: Interpersonal Psychological Theory of Suicide, PB: Perceived Burdensomeness, TB: Thwarted Belongingness, AC: Acquired Capability

CULTURE AND SUICIDE

Collectivism and suicidal behavior

Culture influences one's cognition, emotion, and motivation.25,26,27 Among the various frameworks that have been developed in order to systematically understand disparate cultural influences, Hofstede's concept of ‘individualism’ and ‘collectivism’ has laid a firm foundation for cross-cultural researches.26,28 Collectivistic societies operate upon the core principle of a sense of connectedness and unity. The self is construed in relations to others and evaluated upon the ability to fit in into one's intergroup. Emotions that promote harmonious relationships are emphasized and experienced more frequently. Motives for action are those that enhance one's feeling of relatedness and promote integration into the group (i.e., repression of the self, control over one's desires).24,25,26,27

Korea is one of the most collectivistic societies, which greatly emphasizes family relations.25,28,29,30,31 Although strong bonds with family members and familial support usually act as protective factors against suicide,32 disturbed family relationships, conversely, can have devastating effects.33,34,35 In a nationwide study that examined risk factors of suicide attempts in 2754 adolescents, Bae et al.36 identified the level of intimacy with family as the most powerful predictor of suicide attempt in the potentially depressed group. Hong37 examined the associations between family dysfunction, interpersonal needs, and suicide ideation, and reported that experiences of parental abuse, both verbal and physical, was mediated by thwarted belongingness, and perceived burdensomeness to increase thoughts of suicide in Korean adolescents. While such results are not confined to Korea, Clarke et al.38 identified that suicidal Asians are more likely to report low senses of belongingness than suicidal Caucasians. Hence, it is arguable that impacts of disturbed family relationships can be more hazardous in Korea ironically because it places so much value on the intergroup.39 Furthermore, in a study about sexual preferences and suicide ideation, Kim and Yang40 discovered greater effects of thwarted belongingness, and perceived burdensomeness on suicide ideation in Korean homosexuals than heterosexuals. This result suggests that gay and lesbians worry more about being accepted by significant others. Not only do they worry about fitting in, but Korea's low tolerance towards homosexuals might cause them perceive themselves as a liability towards their family and the society.

Confucianism and suicidal behavior

Another aspect that requires attention in order to understand cultural influences that may affect suicidal behavior in Korea, is Confucianism. Collectivism in Korea has Confucian origins and as a result, stresses parental and filial duties.25 In order to preserve unity within the family (i.e., Collectivism), parents are obliged to provide for their children and children are demanded to meet their parents' expectations (i.e., Confucianism). Negative consequences occur when either the parents or the children are unable to fulfill their role. Ha et al.41 found significant effects of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness in older adults, who were over 65-years-old, and suggested that the inability to provide financial support for their family might play a crucial role. Similarly, Chu and Lee42 identified that older adults were more vulnerable than adolescents toward perceived burdensomeness, and explained that the results are highly attributable to their weakening health and also their fragile financial circumstances.

The burden to comply with a certain role is not parent specific. Often times children experience a corresponding stress, as they are expected to endorse the beliefs and values of their parents, and to live up to their expectations.25 A common phenomenon that children suffer from is ‘education fever,’ which is characterized by the parents' excessive aspiration for their children's education. Contrary to the common belief, major motivations for education fever are not vicarious pleasure or personal satisfaction, but to support children's success.43 In other words, it is a means to provide, hence to fulfill the role as a parent and maintain family bondage. Regardless of the intent, boundless interest of the parents is a cause of academic stress, which has been constantly associated with suicidal behaviors.44,45 According to a national survey in Korea, adolescents rated academic stress as the number one reason for desiring suicide.46 In addition, Seok47 found a significant interaction between perceived burdensomeness and academic stress to predict suicide ideation in female adolescents.

Along the developmental course, experiences of academic stress often have aggravating effects on another common risk factor for suicide: unemployment. While various studies have confirmed the association between unemployment stress and suicide desire,48,49,50 Yoo and Son51 asserted that Koreans might experience a greater degree of stress from unemployment because immense amounts have been invested into their education. As collectivistic societies show a bias towards negative self-appraisal,25 adults who are unable to find a job might falsely attribute the cause of their unemployment to personal inabilities rather than harsh economic circumstances and perceive themselves to be a burden upon their parents, who have made full dedications.

Modernization, generation gaps, and suicidal behavior

So far we have mentioned how Korea's cultural characteristics overlap with the constructs for suicidal behavior identified by the IPTS. Yet, it might be a bit rash to contend that Korea is solely collectivistic. Rapid industrialization and modernization in Korea over the past few decades have promoted individualism, bringing changes in family structure and values. The dominant family structure has changed from extended to nuclear, and the fertility rate has decreased from 4.21 to 1.23 children per woman.52 This transition could have increased experiences of thwarted belongingness, which can be protected by large family size, as household size is negatively correlated with suicide rate.53,54 Also, generation gaps have increased due to younger generations moving toward individualism.55,56,57 This gap would lead to differences in familialistic values-values that reflect family unity and support-between generations. According to Baumann et al.,58 gaps in familialism between mothers and daughters is associated with decreased mutuality and increased externalizing behavior, which in turn predict suicide attempts. Generation gap could also lead to tension between parent and their children,59 which is associated with high risk for suicidal behaviors.60,61

CONCLUSION

In this article, we have reviewed the previous literature on suicide to examine the relationship between the constructs of the IPTS and collectivism in Korea. When positive, collectivistic values can protect individuals from suicide by promoting a sense of oneness.62 However, when unable to abide by its standards, it can also act as a catalyst to suicidal behaviors. While Joiner has posited that the coexistence of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness predict suicidal desire, collectivism in Korea suggests that pathways to suicide might be culturally dependent. For example, in a collectivistic society, inability to fit into an intergroup might cause feelings of loneliness (i.e., thwarted belongingness), which then can be interpreted as a personal liability (i.e., perceived burdensomeness). Such possibilities demand further investigation.

Despite the usefulness of the IPTS to understand suicide, efforts to apply the theory in a Korean population have been scant. For example, the interpersonal needs questionnaire, which measures thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, has been validated only in older adults, limiting its generalizability.63 Other studies have used self-translated versions that lack psychometric validation. In addition, most of the studies have focused solely on suicidal desire, neglecting ‘acquired capability,’ or have not been peer-reviewed. Based on the similarities between Korea's culture and the IPTS, we firmly believe that the theory demands more attention. and that its thorough application holds the potential to enhance the understanding of suicidal behavior in Korea.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Brain Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (NRF-2015M3C7A1028252) and the Korean government (NRF-2015R1A2A2A01003564).

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Beautrais A, et al. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:98–105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Cha CB, Kessler RC, Lee S. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30:133–154. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prinstein MJ. Introduction to the special section on suicide and nonsuicidal self-injury: a review of unique challenges and important directions for self-injury science. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:1–8. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE., Jr The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev. 2010;117:575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill RM, Pettit JW. Perceived burdensomeness and suicideXMLLink_XYZrelated behaviors in clinical samples: current evidence and future directions. J Clin Psychol. 2014;70:631–643. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joiner TE. Why People Die by Suicide. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma J, Batterham PJ, Calear AL, Han J. A systematic review of the predictions of the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicidal Behavior. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;46:34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ribeiro JD, Joiner TE. The interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior: current status and future directions. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65:1291–1299. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solomon RL. The opponent-process theory of acquired motivation: the costs of pleasure and the benefits of pain. Am Psychol. 1980;35:691–712. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.35.8.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christensen H, Batterham PJ, Mackinnon AJ, Donker T, Soubelet A. Predictors of the risk factors for suicide identified by the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behaviour. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219:290–297. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleiman EM, Law KC, Anestis MD. Do theories of suicide play well together? Integrating components of the hopelessness and interpersonal psychological theories of suicide. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55:431–438. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Gordon KH, Bender TW, Joiner TE., Jr Suicidal desire and the capability for suicide: tests of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior among adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:72–83. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barzilay S, Feldman D, Snir A, Apter A, Carli V, Hoven C, et al. The interpersonal theory of suicide and adolescent suicidal behavior. J Affect Disord. 2015;183:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bryan CJ, Clemans TA, Hernandez AM. Perceived burdensomeness, fearlessness of death, and suicidality among deployed military personnel. Pers Individ Diff. 2012;52:374–379. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bryan CJ, Hernandez AM, Allison S, Clemans T. Combat exposure and suicide risk in two samples of military personnel. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69:64–77. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cukrowicz KC, Cheavens JS, Van Orden KA, Ragain RM, Cook RL. Perceived burdensomeness and suicide ideation in older adults. Psychol Aging. 2011;26:331–338. doi: 10.1037/a0021836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Czyz EK, Berona J, King CA. A prospective examination of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior among psychiatric adolescent inpatients. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2015;45:243–259. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ireland JL, York C. Exploring application of the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicidal Behaviour to self-injurious behaviour among women prisoners: proposing a new model of understanding. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2012;35:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ploskonka RA, Servaty-Seib HL. Belongingness and suicidal ideation in college students. J Am College Health. 2015;63:81–87. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2014.983928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poindexter EK, Mitchell SM, Jahn DR, Smith PN, Hirsch JK, Cukrowicz KC. PTSD symptoms and suicide ideation: testing the conditional indirect effects of thwarted interpersonal needs and using substances to cope. Pers Individ Dif. 2015;77:167–172. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson KG, Kowal J, Henderson PR, McWilliams LA, Péloquin K. Chronic pain and the interpersonal theory of suicide. Rehabil Psychol. 2013;58:111–115. doi: 10.1037/a0031390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joiner TE, Jr, Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Selby EA, Ribeiro JD, Lewis R, et al. Main predictions of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior: empirical tests in two samples of young adults. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118:634–646. doi: 10.1037/a0016500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lester D. Suicide and culture. World Cult Psychiatry Res Rev. 2008;3:51–68. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho GH. The confucian origin of the east Asian collectivism. Korean J Soc Pers Psychol. 2007;21:21–54. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hofstede G. Culture and organizations. Int Stud Manag Org. 1980;10:15–41. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol Rev. 1991;98:224. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cho GH. Cultural variations in emotions. Psychol Sci. 1997;6:1–43. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hofstede G, Hofstede GJ, Minkov M. Cultures and organizations. Software of the mind. New York: McGrawHill; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rhee E, Uleman JS, Lee HK, Roman RJ. Spontaneous self-descriptions and ethnic identities in individualistic and collectivistic cultures. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69:142–152. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.1.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Triandis HC. The self and social behavior in differing cultural contexts. Psychol Rev. 1989;96:506–520. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho YB. Suicide ideation, acculturative stress and perceived social support among Korean adolescents. New York: New School University; 2002. Unpublished PhD thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kerr DC, Preuss LJ, King CA. Suicidal adolescents' social support from family and peers: gender-specific associations with psychopathology. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2006;34:99–110. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-9005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park JS, Moon JW. Factors affecting suicidal ideation of the middle and high school students in Korea. Health Soc Sci. 2010;27:105–131. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sabbath JC. The suicidal adolescent-the expendable child. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1969;8:272–285. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)61906-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bae SM, Lee SA, Lee SH. Prediction by data mining, of suicide attempts in Korean adolescents: a national study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:2367–2675. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S91111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hong N. The effects of parental abuse and peer victimization on adolescent's suicidal ideation: the mediating pathway of interpersonal needs and hopelessness. Korean J Soc Welfare. 2012;64:151–175. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clarke DE, Colantonio A, Rhodes AE, Escobar M. Pathways to suicidality across ethnic groups in Canadian adults: the possible role of social stress. Psychol Med. 2008;38:419–431. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707002103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng JK, Fancher TL, Ratanasen M, Conner KR, Duberstein PR, Sue S, et al. Lifetime suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in Asian Americans. Asian Am J Psychol. 2010;1:18–30. doi: 10.1037/a0018799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim S, Yang E. Suicidal ideation in gay men and lesbians in South Korea: a test of the interpersonalXMLLink_XYZpsychological model. Suicide LifeThreat Behav. 2015;45:98–110. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ha J, Song Y, Nam H. The effect of perceived burdensomeness and failed belongingness to elderly suicidal ideation. J Welfare Age. 2012;55:65–84. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chu K, Lee S. Relationships among perceived burdensomeness, hopelesssness, depression, and suicidal ideation in adolescents and elders. Korean J Develop Psychol. 2012;25:31–53. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim J, Lee JG, Lee SK. Understanding of education fever in Korea. KEDI J Educ Policy. 2005;2:7–15. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moon D, Kim Y. A meta-regression analysis on related triggering variables of adolescents' suicidal ideation. Korean J Couns. 2011;12:945–964. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Noh YC, Kim KS, Park HS. The test of gender difference on the causal relationships between adolescent's academic stress and suicidal thoughts. J Kor Soc Comp Inform. 2015;20:133–140. [Google Scholar]

- 46.2014 Adolescent Statistics. [Accessed September 5, 2016]. Available at: http://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_nw/2/6/1/index.board?bmode=read&aSeq=328335.

- 47.Seok YJ. A study on the effect of adolescent's academic stress on suicidal ideation. Seoul: Dongduk Womens University; 2014. Unpublished master's thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chang SS, Gunnell D, Sterne JA, Lu TH, Cheng AT. Was the economic crisis 1997-1998 responsible for rising suicide rates in East/Southeast Asia? A time-trend analysis for Japan, Hong Kong, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Thailand. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:1322–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Laanani M, Ghosn W, Jougla E, Rey G. Impact of unemployment variations on suicide mortality in Western European countries (2000-2010): authors' reply. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69:819–820. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-205382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park JS, Lee JY, Kim SD. A study for effects of economic growth rate and unemployment rate to suicide rate in Korea. Korean J Prevent Med. 2003;36:85–91. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yoo GS, Son HG. Effects of risk & protective factors on suicidal ideation in undergraduate students: focusing on the interpersonal needs & reasons for living. Korean J Fam Relat. 2015;22:75–100. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Population trends and projections of the world and Korea. [Accessed September 12, 2016]. Avaliable at: http://kostat.go.kr/portal/eng/pressReleases/8/8/index.board?bmode=read&aSeq=347597&pageNo=&rowNum=10&amSeq=&sTarget=&sTxt=

- 53.Denney JT, Rogers RG, Krueger PM, Wadsworth T. Adult suicide mortality in the United States: marital status, family size, socioeconomic status, and differences by sex. Soc Sci Quart. 2009;90:1167–1185. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shah A. The relationship between elderly suicides rates, household size and family structure: a cross-national study. Int J Psychiatr Clin Pract. 2009;13:259–264. doi: 10.3109/13651500902887656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chong HS. Case analyses of parent-college student inter-generational conflict: multi-levelled approach to actual communication conflict. Speech Commun. 2009;11:7–46. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Na EY, Duckitt J. Value consensus and diversity between generations and genders. Soc Indic Res. 2003;62:411–435. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nam SH. A study on psychological mechanism of copycat suicidal ideation among adolescents. Honam Univ Inst Hum. 2008:51–87. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baumann AA, Kuhlberg JA, Zayas LH. Familism, mother-daughter mutuality, and suicide attempts of adolescent Latinas. J Fam Psychol. 2010;24:616–624. doi: 10.1037/a0020584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zayas LH, Hausmann-Stabile C, Kuhlberg J. Can better mother-daughter relations reduce the chance of a suicide attempt among Latinas? Depress Res Treat. 2011;2011:403602. doi: 10.1155/2011/403602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Handy S, Chithiramohan R, Ballard C, Silveira W. Ethnic differences in adolescent self-poisoning: a comparison of Asian and Caucasian groups. J Adolesc. 1991;14:157–162. doi: 10.1016/0140-1971(91)90028-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hollis C. Depression, family environment, and adolescent suicidal behavior. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:622–630. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199605000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim YJ, Lee SJ, Park YJ. Relationship between collectivism and suicidal ideation in old age. Indian J Sci Technol. 2015;8:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee HY, Lee JA, Oh KS. Validation of the Korean version of interpersonal needs questionnaire (K-INQ) for older adults. Korean J Clin Psychol. 2015;34:291–313. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ha JM, Seol YU, Jwa MG. The effect of perceived burdensomeness and failed belongingness to youth’s suicidal ideation. Soc Sci Res Rev Kyungsung Univ. 2010;26:223–246. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim BM, You S. Social connections and emotion regulation in suicidal ideation among individuals with interpersonal trauma. Korean J Clin Psychol. 2012;31:731–748. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chu KJ, Lee SY. Relationships among perceived burdensomeness, hopelessness, depression, and suicidal ideation in adolescents and elders. Korean J Dev Psychol. 2012;25:31–53. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ha J, Song Y, Nam H. The effect of perceived burdensomeness and failed belongingness to elderly suicidal ideation. J Welfare Aged. 2012;55:65–84. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hong NM, Chung YS. Path analysis on adolescent's suicidal ideation: a comparison of adolescent suicide attempters and non-attempters. J Korean Soc Child Welfare. 2012;40:255–283. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Park AR, Chun JS. A study on relationship between interpersonal relationships and suicide ideation among alcoholics: focusing on the mediating effects of depression. Korean Ins Health Soc Affairs. 2014;34:379–407. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim S, Yang E. Suicidal ideation in gay men and lesbians in South Korea: a test of the interpersonal-psychological model. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2015;45:98–110. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sung K, Kwon YS, Hyun MH. The associations between aggression, acquired capability for suicide and suicidal behavior in male alcohol use disorders. Korean J Health Psychol. 2015;20:253–265. [Google Scholar]