Abstract

Acuteliver failure (ALF) has a high mortality rate and is characterized by massive hepatocyte destruction. Although microRNAs (miRNAs) play an important role in manyliver diseases, the role of miRNAs in ALF development is unknown. In this study, the murine ALF model was induced by intraperitoneal injection of D-galactosamine/lipopolysaccharide (D-GalN/LPS). Compared with saline-treated mice, miR-24 was distinctly down-regulated post D-GalN/LPS challenge in vivo and D-galactosamine/tumor necrosis factor (D-GalN/TNF) challenge in vitro, which was confirmed by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. Meanwhile, the mRNA and protein levels of the BH3-only-domain-containing protein BIM were upregulated after challenge both in vivo and in vitro. Previous studies have demonstrated that hepatocyte apoptosis is a distinguishing feature of D-GalN/LPS-associated liver failure. In this study, D-GalN/LPS-challenged mice showed higher alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase levels, more severe liver damage, increased numbers of apoptotic hepatocytes and higher levels of caspase-3 compared with saline-treated mice. In D-GalN/TNF-treated BNLCL2 cells, miR-24 overexpression attenuated apoptosis.Furthermore, miR-24 overexpression reduced BIM mRNA and protein levels in vitro. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that miR-24 regulates hepatocyte apoptosis via BIM during ALF development, suggesting that miR-24 is a novel onco-miRNA that may provide potential therapeutic targets for ALF.

Keywords: MiR-24, BIM, acute liver failure, apoptosis

Introduction

Acute liver failure (ALF) is a fatal liver disease that is associated with high mortality rates worldwide (40%-80%) [1]. Autoimmune hepatitis, alcohol consumption, viral hepatitis, and hepatotoxinsare confirmed ALF trigger factors [2]. The best treatment for ALF is liver transplantation [3], but the lack of donor livers often limits transplantation. During ALF development, necrosis and hepatocyte apoptosis are key pathologic traits, but the precise underlying mechanism remains to be elucidated [4].

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are non-coding RNA molecules of 22-26 nucleotides that regulate gene expression [5]. By interacting with the 3’ untranslated region (UTR) of target mRNAs, negatively influencing protein expression by destabilizing the message or inhibiting translation [6-10]. miRNAs take part in a number of biological processes including development, differentiation, cell proliferation, apoptosis and metabolism [11-13]. It has also been reported that miRNAs play an important role in liver regeneration and might contribute to spontaneous ALF recovery [14]. miR-24 plays a critical role in many biological processes including erythroid differentiation, DNA-repair, cell cycle regulation and programmed cell death [15-20]. Previous reports have shown that mir-24 negatively regulates apoptosis in frogs and mice [21]. It has also been reported that miR-24 is involved in hepatocellular carcinogenesis [22], hepatic lipid accumulation [23] and liver stem cell differentiation [18]. Although mir-15 and mir-16 play important roles in ALF development [24], the role of the mir-24 in this disease is unknown, as is whether there is a link between mir-24 and hepatocyte apoptosis. In this study, we demonstrate that mir-24 regulates hepatocyte apoptosis in a murine ALF model.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male BALB/c mice weighing 18-22 g (6-8 weeks old) were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co. Ltd. (Beijing, China) and housed under laboratory conditions with free access to food and water. Animals were treated as recommended in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All animal experiments were approved by the Nanjing Medical University Laboratory Animals Care and Use Committee.

Experimental ALF model

Experimental mice were intraperitoneally injected with 800 mg/kg D-galactosamine (D-GalN) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 10 µg/kg lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Sigma-Aldrich) aspreviously described [25], meanwhile the three control groups were separately administered the same doses of D-GalN, LPS or saline only. The challenged mice were sacrificed at different time points (0, 1, 3, 5, 7, 9 and 24 h) for blood and liver tissue. Serum was used for biochemical analyses and ELISA before sacrifice. Liver tissue was collected for miRNA analysis, qRT-PCR andwestern blot; the remaining tissues were used for histopathology and immunohistochemistry.

Cytokine assays

Serum tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels were measured in the D-GalN/LPS-challenged mice at various time points using the Valukine ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Liver enzymes measurements

The serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and alanine aminotransferase (AST) are indexes of hepatocellular injury. ALT and AST activity were measured in the serum of mice by a standard autoanalyzer (Hitachi 7600-10, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

Hematoxylin and eosin staining

Liver tissues were recovered, fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections (5 mm thick) were affixed to slides, deparaffinized and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for morphologic examination under light microscopy.

Immunohistochemical caspase-3 analysis

Caspases are key mediators of apoptosis, and caspase-3, is a death protease [26]. Paraffin-embedded liver sections were treated with pH 9.0 antigen retrieval buffer (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) at 100°C for 10 min. The slides were then incubated with rabbitanti-mouse caspase-3 antibody (1:200) (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) for 1 h at room temperature, then washed three times in Tris-buffered saline (TBS). Finally, they were incubated with Envision-polymer horseradish peroxidase (HRP) rabbit antibody (Dako) for 1 h at room temperature. Peroxidase activity was confirmed using diaminobenzidine.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from liver tissues and cultured cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), reverse-transcribed, and the resulting cDNA was used with miRNA-specific TaqMan primers and TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Advanced Biotechnologies Inc., Eldersburg, MD, USA) to determine miRNA expression, with RNU6B as the endogenous control. Quantitative real-time PCR analysis was performed using SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and a Step One Plus real-time PCR system (Advanced Biotechnologies Inc.). The levels of murine BIM, TNFα and IL-6 expression were normalized to b-actin. All reactions were performed in triplicate and repeated three times. All primer sequences are given in Table 1. The comparative threshold cycle (Ct) method was used to measure relative changes in expression; 2-ΔΔCT represents the fold change in expression, as previously described [27].

Table 1.

Sequences for qRT-PCR amplification primers

| U6 | FP: 5’-CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA-3’ |

| RP: 5’-AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT-3’ | |

| β-Actin | FP: 5’-CTAGGCACCAGGGTGTGAT-3’ |

| RP: 5’-TGCCAGATCTTCTCCATGTC-3’ | |

| TNF-α | FP: 5’-CCACCACGCTCTTCTGTCTAC-3’ |

| RP: 5’-TGGCTACAGGCTTGTCACT-3’ | |

| IL-6 | FP: 5’-CCACTTCACAAGTCGGAGGCTTA-3’ |

| RP: 5’-GCAAGTGCATCATCGTTGTTCATAC-3’ | |

| Bim | FP: 5’-CACCAGCACCATAGAAGAA-3’ |

| RP: 5’-ATAAGGAGCAGGCACAGA-3’ | |

| miR-24 | RT: 5’-CTCAACTGGTGTCGTGGAGTCGGCAATTCAGTTGAGCTGTTCCT-3’ |

| FP: 5’-ACACTCCAGCTGGGTGGCTCAGTTCAGCAG-3’ | |

| RP: 5’-CTCAACTGGTGTCGTGGAGTCGGCAATTCAG-3’ |

Western blots

Total proteins from liver tissues or cells were lysed in lysis buffer (Beyotime, Nantong, China), separated on a 10% sodiumdodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to an Immobilon-P-polyvinylide nedifluoride membrane (Millipore, Danvers, MA, USA). After blocking the membranes in 5% skim milk for 1 h, they were incubated with anti-BIM (Abcam), anti-caspase-3 (Abcam) or anti-β-actin antibody (Abcam) overnight at 4°C. After washing with TBS/Tween-20, the membranes were incubated for 2 h at room temperature with HRP-conjugated goat anti rabbit IgG (1:2000, Sigma-Aldrich). Immunoreactive bands were detected with an ECLwestern blotting detection system (Pierce/Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) by enhanced chemiluminescence.

Cell lines and the in vitro induction of hepatocyte apoptosis

Normal murine embryonic liver cells (BNLCL2) were purchased from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Beijing, China) and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 4 mM glutamate and 1,000 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco/Invitrogen). To induce hepatocyte apoptosis, 1 mg/ml D-GalN (Sigma-Aldrich) and 100 ng/ml TNFα (Sigma-Aldrich) were added to the culture medium; mock treated cells were grown in culture medium only. Part of the experimental group were collected for total RNA extraction and western blots, while the remainder were used for apoptosis assays using the Annexin-V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit (KeyGEN, Nanjing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Annexin-V-positive, PI-negative cells were defined as early apoptotic cells, whereas the necrotic cells were Annexin-V-negative, PI-positive. Analyses were performed on a Beckman Gallios Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). Each measurement was repeated three times.

Plasmid construction and luciferase assays

BNLCL2 Cells (5×104) were seeded in 24-well plates and cultured for 24 h. BIM reporter luciferase plasmid (100 ng), pGL3-BIM-3’UTR (wt/mut), or control luciferase plasmid, and 5 ng pRL-TK Renilla plasmid (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was transfected into the cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Luciferase and Renilla signals were measured 48 h after transfection using a Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay Kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Cell transfection

BNLCL2 cells were cultured in a six-well culture plate at a density of 2-4×105 cells per well for 24 h, then the cells were transfected with 100 n MmiR-24 mimic, 200 n MmiR-24 inhibitor (GenePharma, Shanghai, China) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions for 24 h. The negative controls included 100 nM non-specific mimic, 200 nM non-specific inhibitor and FAM-negative control miRNA (GenePharma). Each measurement was performed at least three times.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the means ± SD (standard deviation) from at least three independentexperiments. Unpaired Student’s t test wasused to determine the significance, using Prism 6 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) software. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Liver injury in the D-GalN/LPS-induced mice

Challenged mice were injected with D-GalN/LPS, while control mice were administered D-GalN or LPS alone, or saline to evaluate liver injury. The mice were then sacrificed at specific time points (0, 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9 h) to obtain blood and liver samples to examine liver enzymes, histopathology and inflammatory cytokines. In the challenged mice, the mortality rate was 60% and 80% at 7 h and 24 h, respectively, while no deaths were detected in the three control groups (data not shown). Serum ALT and AST levels are standard biomarkers for evaluating liver injury, and both ALT (Figure 1A) and AST (Figure 1B) levels showed gradual elevation after D-GalN/LPS stimulation, peaking significantly at 7 h (P<0.001, D-GalN/LPS group vs control groups). Meanwhile there was no obvious change in ALT and AST levels in D-GalN-, LPS-, or saline-challenged controls.

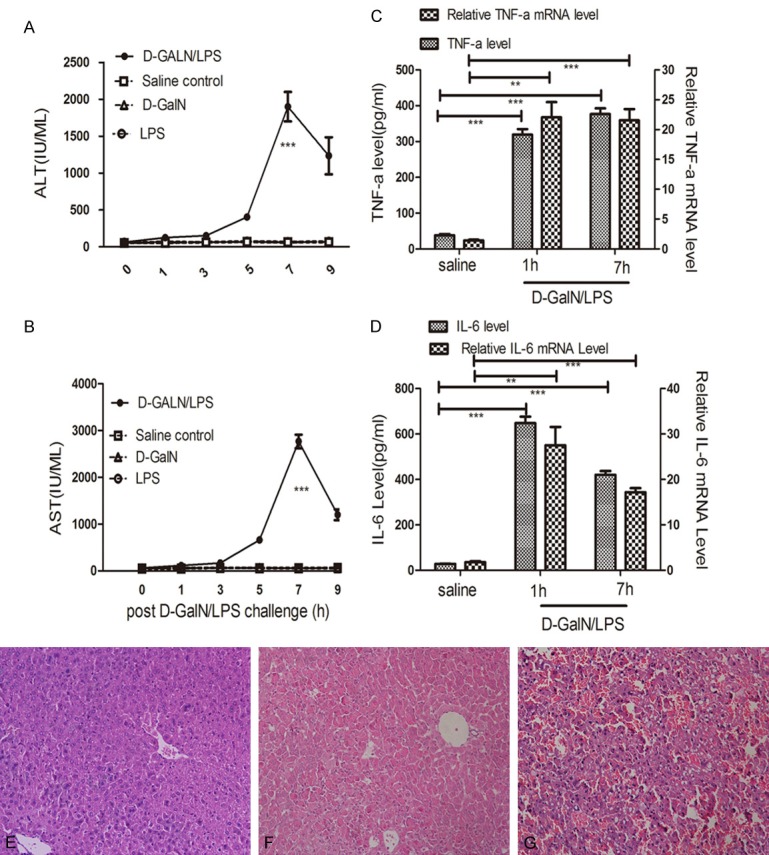

Figure 1.

Liver injury and Histopathology. Serum ALT (A) and AST (B) release increased gradually and peaked at 7 h post D-GalN/LPS challenge, compared with D-GalN, LPS or saline injections (values are expressed as IU/ml). The mRNA and serum concentrations of TNFα (C), IL-6 (D) in the challenged group increased obviously at 1 h and 7 h time points compared with saline-treated group. (E) Representative hematoxylin- and eosin-stained tissues. No abnormity was detected at saline-treated group. (F) Increased inflammatory cells, slightly congested sinusoids and hepatocellular disintegration were detected at the 5 h time point post D-GalN/LPS-challenge. (G) Extreme damage in the liver tissue at 7 h post D-GalN/LPS-challenge. Results are presented as mean ± SD; **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 versus the control group. There are four groups, D-GalN/LPS, D-GalN, LPS, and saline, with six time points (0, 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9 h) for each group. There were three mice per time point for each group.

TNFα and IL-6 play important roles in hepatocyte apoptosis, which has been identified in D-GalN/LPS-induced liver failure [28]. TNFα mRNA levels in the challenged group at 1 h (P<0.01) and 7 h (P<0.001) were significantly higher compared with the saline-treated group (Figure 1C); accordingly serum concentrations of TNFα in the challenged group were higher than the saline-treated group at 1 h (P<0.001) and 7 h (P<0.001). A similar pattern was detected for IL-6 (Figure 1D). No other changes in TNFα and IL-6 protein and mRNA levels were detected at the other time points (data not shown). Hematoxylin and eosin histopathology of saline-treated mice showed no changes (Figure 1E), while increased inflammatory cells, slightly congested sinusoids and hepatocellular disintegration were detected at the 5 h (Figure 1F) time point in the livers of D-GalN/LPS-challenged mice. Severe congestion, hepatocellular disintegration throughout the entire liver and large numbers of inflammatory cells were found in the ALF mice at 7 h (Figure 1G).

miR-24 downregulation and BIM upregulation in the ALF model

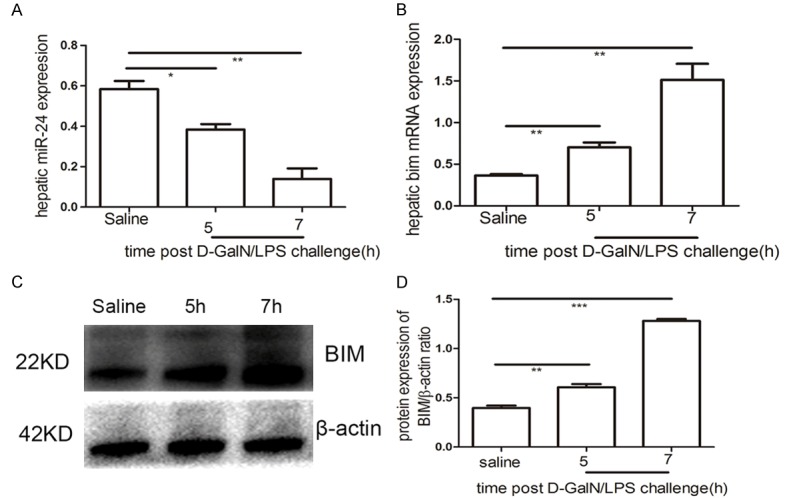

The levels of miR-24 and BIM mRNA expression were confirmed by qRT-PCR in the ALF model and saline-treated mice; miR-24 expression was highly down-regulated at 5 h (P<0.05) and 7 h (P<0.01) in the ALF model compared with saline-treated mice (Figure 2A). Hepatic BIM mRNA expression was distinctly higher at 5 h (P<0.01) and 7 h (P<0.01) post D-GalN/LPS challenge compared with the control group (Figure 2B). Consistent with the qRT-PCR results, hepatic BIM protein levels were up-regulated in the ALF model at 5 h (P<0.01) and 7 h (P<0.001) compared with the control group (Figure 2C, 2D).

Figure 2.

miR-24 downregulation and BIM upregulation. qRT-PCR analysis of miR-24 (A) and BIM (B) at 5 h and 7 h post D-GalN/LPS challenge compared with saline-treated group. (C) Western blotting analysis of BIM protein expression in the control and experimental groups. (D) Signal was quantified and data was normalized to b-actin. Results are presented as mean ± SD; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 versus the control group.

Increased hepatocyte apoptosisin the ALF model

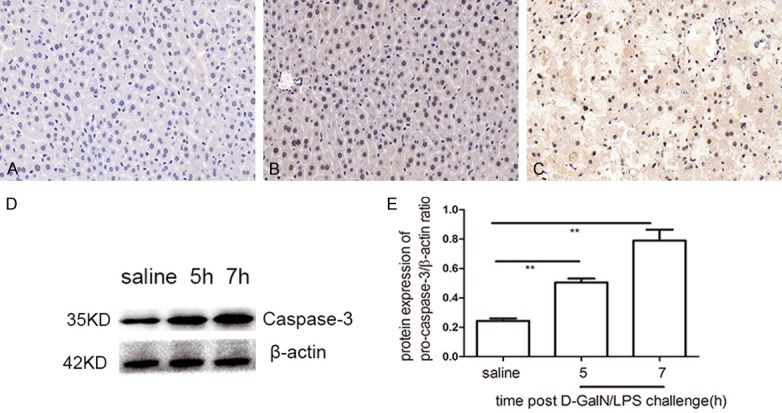

The analysis of hepatocyte apoptosis is shown in Figure 3, which shows caspase-3 immunohistochemistry and western blot data. While there were no detectable caspase-3-positive cells in the saline-treated group (Figure 3A), caspase-3-positive cells were found in the liver of experimental mice at 5 h post-challenge (Figure 3B). Furthermore, a substantial increase in caspase-3-positive staining was observed at 7 h post-challenge (Figure 3C). To confirm these results, we performed western blot analyses of caspase-3; the challenged mice showed increased caspase-3 at both the 5 h (P<0.01) and 7 h (P<0.01) time points compared with saline-treated mice (Figure 3D), which was consistent with the immunohistochemical results.

Figure 3.

Hepatocyte apoptosis analysis. Apoptosis was observed by caspase-3 immunohistochemical staining in the liver tissues of D-GalN/LPS and saline treatment. A. In saline-treated group, no caspase-3+ cells was detected. B. A small amount of caspase-3+ cells was found at 5 h post D-GalN/LPS challenge. C. A substantial increase in caspase-3-positive staining was observed at 7 h post D-GalN/LPS challenge. D. Western blot analysis of caspase-3.Compared with saline-treated group, thecaspase-3 protein expressionincreased obviously at 5 h and 7 h post D-GalN/LPS challenge. E. The signal was quantified and data was normalized to b-actin. Results are presented as mean ± SD; **P<0.01 versus the control group.

miR-24 targeted Bim mRNA3’UTR in hepatocytes

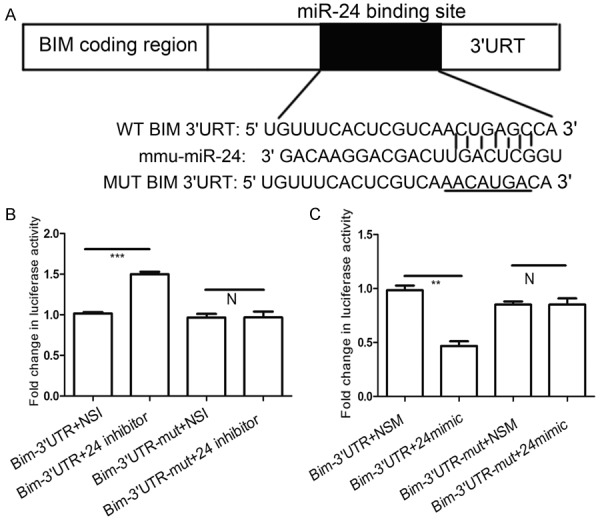

To confirm the predicted miR-24 binding sites in the 3’UTR of Bim (Figure 4A), we used the luciferase report assay in BNLCL2 cells.pGL3-BIM-3’UTR (wt/mut) luciferase report plasmids and miR-24 mimic, inhibitor, NSM, NSI were transfected into cells. There was no difference of luciferase activity between the cells transfect ed with Bim-3’UTR-mut and miR-24 inhibitor and the cells transfected with Bim-3’UTR-mut and miR-24 NSI (Figure 4B). However, compared with the cells transfected with Bim-3’UTR and miR-24 NSI, theluciferase activity elevated by more than 32% (P<0.001) in the cells transfected with Bim-3’UTR and miR-24 inhibitor (Figure 4B). Furthermore, we found that the luciferase activity in the cells transfected Bim-3’UTR and miR-24 mimic was reduced by approximately 52% (P<0.01) compared the cells transfected with Bim-3’UTR and NSM (Figure 4C). We observed no difference in luciferase activity between the cells transfected with Bim-3’UTR-mut and miR-24 mimic and the cells transfected with Bim-3’UTR-mut and miR-24 NSM (Figure 4C). From these data, weconclude that miR-24 targeted Bim mRNA3’UTR in hepatocytes during acute liver failure.

Figure 4.

miR-24 targetes Bim mRNA3’UTR in hepatocytes. The data from targetscan reveals that Bim is a predicted target gene of miR-24 (A) The predicted binding sites of miR-24 targeting Bim mRNA3’UTR. pGL3-BIM-3’UTR (wt/mut) luciferase report plasmids were transfected with miR-24 inhibitor (B) or miR-24 mimic (C) While miR-24 non-specific inhibitor or non-specific mimic were transfected as control group. Data represent the mean value of three independent experiments. Mean ± SEM. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and N, P>0.05.

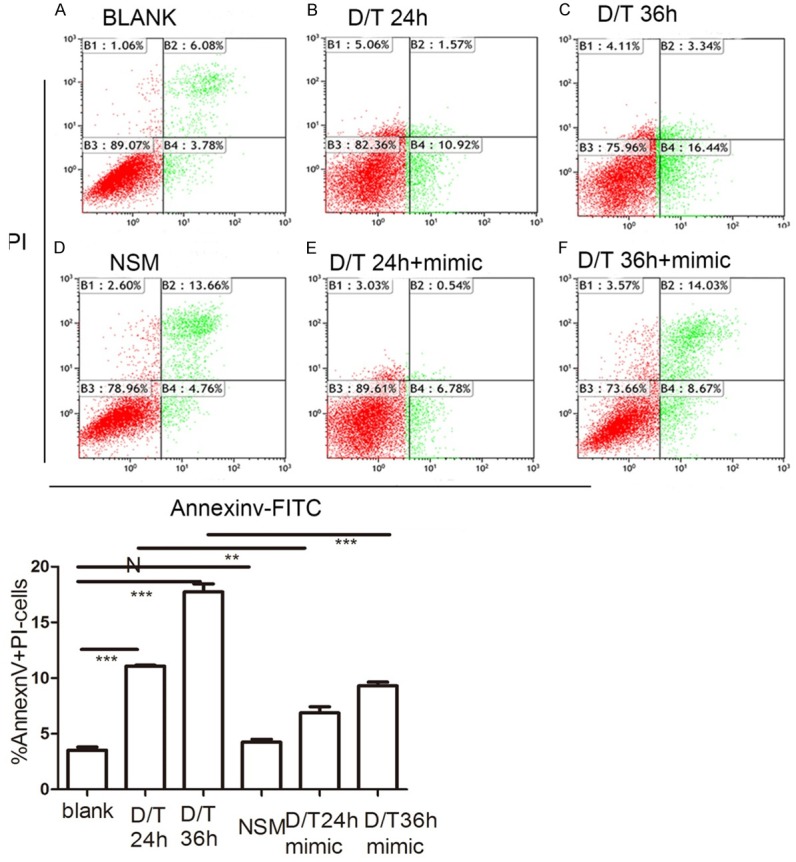

miR-24 overexpression attenuated apoptosis in vitro

From the aforementioned results, it was next necessary to investigate whether miR-24 regulated hepatocyte apoptosis in vitro. The apoptotic rate was 3.53% in the control group (Figure 5A), while flow cytometry data showed an apoptotic rate of 11.07% and 17.74% in BNLCL2 cells 24 h (Figure 5B) and 36 h (Figure 5C) after D-GalN/TNF stimulation, respectively. While there was no change in the apoptotic rate when BNLCL2 cells were transfected with a non-specific miRNA mimic (Figure 5D) compared with controls, miR-24 mimic resulted in a decreased apoptotic rate 24 h (6.87%) (Figure 5E) and 36 h (9.31%) (Figure 5F) after D-GalN/TNFα stimulation.

Figure 5.

miR-24 overexpression attenuate apoptosis in BNLCL2 cells. BNLCL2 cells were transfected with miR-24 mimic or non-specific mimic, followed by various incubation times with D-GalN/TNF or mock treatment, and thenstained with Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide. Representative apoptosis flow cytometry data for the different conditions are shown. Apoptotic cells were AnnexinV+/PI-. The panel showed blank treatment (A), D-GalN/TNF challenge for 24 h (B) or 36 h (C) The cells were transfected with miR-24 non-specific mimic (D), then treated with DMEM only.The cells transfected with miR-24 mimic were treated with D-GalN/TNF for 24 h (E) or 36 h (F). Data represent the mean value of three independent experiments. Mean ± SEM. NSM versus BLANK, N, P>0.05; D/T24 h+miR-24 mimic versus D/T24 h, **, P<0.01; D/T36 h+miR-24 mimic versus D/T36 h, ***, P<0.001.

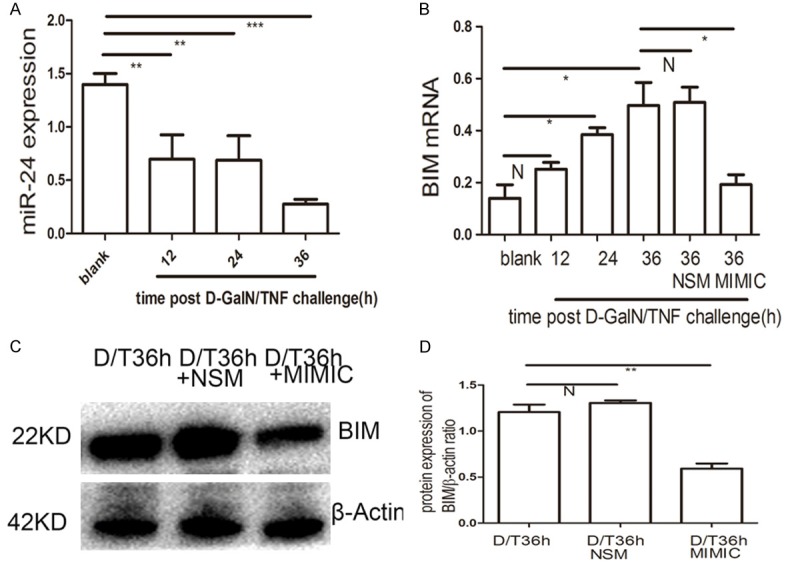

miR-24 mimic attenuated BIM expression in vitro

Consistent with the in vivo results (Figure 2B), in vitro experiments revealed that miR-24 was down-regulated 36 h after D-GalN/TNF challenge compared with controls (P<0.001) (Figure 6A). Conversely, BIM mRNA was up-regulated 36 h post D-GalN/TNF challenge (P<0.05) (Figure 6B), which also correlated withour in vivo data (Figure 2B). No significant difference in BIM mRNA levels were detected in the cells transfected with non-specific miRNA mimics post D-GalN/TNF challenge (Figure 6B); however, BIM mRNA was downregulated in cells transfected with miR-24 mimic post D-GalN/LPS challenge (P<0.05) (Figure 6B). Accordingly, BIM protein expression was down-regulated in cells transfected with miR-24 mimic 36 h post D-GalN/TNF challenge (Figure 6C, 6D) (P<0.001). From the aforementioned data, we conclude that miR-24 regulates BIM at both the mRNA and protein levels in vitro.

Figure 6.

miR-24 mimic reduces BIM expression in BNLCL2 cells. A. qRT-PCR analysis of miR-24 at different time points post D-GalN/TNF challenge. B. BIM qRT-PCR analysis in BNLCL2 cells transfected with miR-24 mimic or miR-24 non-specific mimic, then followed by stimulation of D-GalN/TNF for 36 h, while the blank group were treated only with DMEM. C, D. BIM western blotting in BNLCL2 cells transfected with miR-24 mimic or miR-24 non-specific mimic. Data represent the mean value of three independent experiments. Mean ± SEM. N, P>0.05; *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

Discussion

ALF induced by viral hepatitis,alcohol or other hepatotoxic drugs are liver damaging processes, in which TNFα plays a critical role [29]. Previous findings have suggested that miRNAs play arolein regulating death receptors and pro-and anti-apoptotic genes [30]. However, the relationship between miRNAs and TNF-α-dependent apoptosis has not been fully demonstrated in themurine ALF model. In light of this, we speculated that miRNAs may regulate hepatocyte apoptosis in ALF.

The D-GalN/LPS-induced murine ALF model is dependent on TNFα production [31]. Our ALF model was confirmed by histopathology and biochemistry, through which we also revealed that miR-24 was down-regulated and Bim was upregulated. Furthermore, our data demonstrated that miR-24 regulated the key apoptotic gene BIM during ALF. Thus, we conclude that miR-24 regulated hepatocyte apoptosis via BIM in the murine ALF model. These findings are consistent with previous reports, which found that miR-24 regulated apoptosis by targeting BIM in murine cardiomyocytes [21] and pancreatic carcinoma [32]. Therefore, we conclude that the down-regulation of hepatic miR-24 also contributes to hepatocyte apoptosis by regulating BIM in this ALF model.

miRNAs regulate protein expression by inducing mRNA degradation and repressing translation [33]. In this study, we revealed that miR-24 targeted Bim mRNA3’UTR in hepatocytes using the luciferase analysis system. Our data showed that miR-24 mimic reduced the expression of BIM mRNA and protein, which demonstrated that miR-24 regulated hepatocyte apoptosis by suppressing Bim viamRNA degradation and translation.

BIM belongs to the pro-apoptotic BCL-2 family and is located in the outer mitochondrial membrane, which contributes to TNF-a-induced apoptotic signaling events [34,35]. In our experiments, miR-24 was down-regulated in the ALF livers in vivo and in hepatocytes treated with D-GalN/TNF in vitro. Conversely, we showed that BIM mRNA and protein levels were up-regulated during ALF, both in vivo and in vitro. Meanwhile, miR-24 overexpression reduced the mRNA and protein expression of BIM. Similarly, miR-24 mimic attenuated the apoptotic rate. These data are consistent with the TargetScan database, which shows BIM is a putative miR-24 target. Our findings suggest that miR-24 regulates hepatocyte apoptosis by suppressing BIM.

Apoptosis can be triggered by the death receptor (extrinsic) and the mitochondrial (intrinsic)pathways [36]. TNF contributes to hepatocyte apoptosis in ALF via the death receptor pathway. During ALF, interactions between TNF and TNF Receptor 1 trigger a series of intracellular events, which culminate in the activation of caspase-3, -8 and -9 [37]. Caspases are crucial mediators of programmed cell death, and caspase-3 is a frequently activated death protease that catalyzes the specific cleavage of many key cellular proteins [26]. We showed that TNF was up-regulated in the liver tissue and serum during ALF in vivo. The increased levels of apoptosis were also confirmed by progressively increased numbers of caspase-3-positive cells over time in the ALF livers. The level of caspase-3 protein expression was also determined by western blot. Taken together, our findings demonstrate that apoptosis plays an important role in ALF.

During in vivo and in vitro ALF, miR-24 was down-regulated, while BIM was up-regulated. Moreover, miR-24 overexpression reduced BIM mRNA and protein levels. BIM induction by palmitate induces apoptosis in hepatocytes [38], which is a critical contributor to TNF-a-induced hepatocyte apoptosis in vivo. We speculate that miR-24 overexpression reduces BIM expression, which in-turn downregulates downstream genes, including caspase-3, consequently attenuating hepatocyte apoptosis.These data suggest that miR-24 regulates hepatocyte apoptosis by BIM during ALF; however, the precise underlying mechanism that connects miR-24 and BIM remains to be explored. To this end, the upstream regions of miR-24 are currently being investigated.

In summary, our research revealed that miR-24 regulates hepatocyte apoptosis via targeting BIM. These findings may provide a new therapeutic strategy for ALF treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by National Nature Science Foundation of China (81100318, 81270438) and a grant (81273261) from The National Nature and Science fund. We appreciate the constructive comments from Prof Lianbao Kong and technical support from Prof Liyong Pu.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Vaquero J, Blei AT. Etiology and management of fulminant hepatic failure. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2003;5:39–47. doi: 10.1007/s11894-003-0008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torisu T, Nakaya M, Watanabe S, Hashimoto M, Yoshida H, Chinen T, Yoshida R, Okamoto F, Hanada T, Torisu K, Takaesu G, Kobayashi T, Yasukawa H, Yoshimura A. Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 protects mice against concanavalin A-induced hepatitis by inhibiting apoptosis. Hepatology. 2008;47:1644–1654. doi: 10.1002/hep.22214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Russo FP, Parola M. Stem and progenitor cells in liver regeneration and repair. Cytotherapy. 2011;13:135–144. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2010.545386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu Z, Han M, Chen T, Yan W, Ning Q. Acute liver failure: mechanisms of immune-mediated liver injury. Liver Int. 2010;30:782–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ambros V. MicroRNA pathways in flies and worms: growth, death, fat, stress, and timing. Cell. 2003;113:673–676. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00428-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao Y, Samal E, Srivastava D. Serum response factor regulates a muscle-specific microRNA that targets Hand2 during cardiogenesis. Nature. 2005;436:214–220. doi: 10.1038/nature03817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao Y, Srivastava D. A developmental view of microRNA function. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruvkun G. The perfect storm of tiny RNAs. Nat Med. 2008;14:1041–1045. doi: 10.1038/nm1008-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brennecke J, Hipfner DR, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM. Bantam encodes a developmentally regulated microRNA that controls cell proliferation and regulates the proapoptotic gene hid in Drosophila. Cell. 2003;113:25–36. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reinhart BJ, Slack FJ, Basson M, Pasquinelli AE, Bettinger JC, Rougvie AE, Horvitz HR, Ruvkun G. The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2000;403:901–906. doi: 10.1038/35002607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.John K, Hadem J, Krech T, Wahl K, Manns MP, Dooley S, Batkai S, Thum T, Schulze-Osthoff K, Bantel H. MicroRNAs play a role in spontaneous recovery from acute liver failure. Hepatology. 2014;60:1346–1355. doi: 10.1002/hep.27250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lal A, Kim HH, Abdelmohsen K, Kuwano Y, Pull Pullmann R Jr, Srikantan S, Subrahmanyam R, Martindale JL, Yang X, Ahmed F, Navarro F, Dykxhoorn D, Lieberman J, Gorospe M. p16 (INK4a) translation suppressed by miR-24. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lal A, Navarro F, Maher CA, Maliszewski LE, Yan N, O’Day E, Chowdhury D, Dykxhoorn DM, Tsai P, Hofmann O, Becker KG, Gorospe M, Hide W, Lieberman J. miR-24 Inhibits cell proliferation by targeting E2F2, MYC, and other cell-cycle genes via binding to “seedless” 3’UTR microRNA recognition elements. Mol Cell. 2009;35:610–625. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lal A, Pan Y, Navarro F, Dykxhoorn DM, Moreau L, Meire E, Bentwich Z, Lieberman J, Chowdhury D. miR-24-mediated downregulation of H2AX suppresses DNA repair in terminally differentiated blood cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:492–498. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogler CE, Levoci L, Ader T, Massimi A, Tchaikovskaya T, Norel R, Rogler LE. MicroRNA-23b cluster microRNAs regulate transforming growth factor-beta/bone morphogenetic protein signaling and liver stem cell differentiation by targeting Smads. Hepatology. 2009;50:575–584. doi: 10.1002/hep.22982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker JC, Harland RM. microRNA-24a is required to repress apoptosis in the developing neural retina. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1046–1051. doi: 10.1101/gad.1777709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Q, Huang Z, Xue H, Jin C, Ju XL, Han JD, Chen YG. MicroRNA miR-24 inhibits erythropoiesis by targeting activin type I receptor ALK4. Blood. 2008;111:588–595. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-092718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qian L, Van Laake LW, Huang Y, Liu S, Wendland MF, Srivastava D. miR-24 inhibits apoptosis and represses Bim in mouse cardiomyocytes. J Exp Med. 2011;208:549–560. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hatziapostolou M, Polytarchou C, Aggelidou E, Drakaki A, Poultsides GA, Jaeger SA, Ogata H, Karin M, Struhl K, Hadzopoulou-Cladaras M, Iliopoulos D. An HNF4alpha-miRNA inflammatory feedback circuit regulates hepatocellular oncogenesis. Cell. 2011;147:1233–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ng R, Wu H, Xiao H, Chen X, Willenbring H, Steer CJ, Song G. Inhibition of microRNA-24 expression in liver prevents hepatic lipid accumulation and hyperlipidemia. Hepatology. 2014;60:554–564. doi: 10.1002/hep.27153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.An F, Gong B, Wang H, Yu D, Zhao G, Lin L, Tang W, Yu H, Bao S, Xie Q. miR-15b and miR-16 regulate TNF mediated hepatocyte apoptosis via BCL2 in acute liver failure. Apoptosis. 2012;17:702–716. doi: 10.1007/s10495-012-0704-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mignon A, Rouquet N, Fabre M, Martin S, Pages JC, Dhainaut JF, Kahn A, Briand P, Joulin V. LPS challenge in D-galactosamine-sensitized mice accounts for caspase-dependent fulminant hepatitis, not for septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1308–1315. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.4.9712012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porter AG, Janicke RU. Emerging roles of caspase-3 in apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:99–104. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 (-Delta Delta C (T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuhla A, Eipel C, Siebert N, Abshagen K, Menger MD, Vollmar B. Hepatocellular apoptosis is mediated by TNFalpha-dependent Fas/FasLigand cytotoxicity in a murine model of acute liver failure. Apoptosis. 2008;13:1427–1438. doi: 10.1007/s10495-008-0269-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wielockx B, Lannoy K, Shapiro SD, Itoh T, Itohara S, Vandekerckhove J, Libert C. Inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases blocks lethal hepatitis and apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor and allows safe antitumor therapy. Nat Med. 2001;7:1202–1208. doi: 10.1038/nm1101-1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garofalo M, Condorelli GL, Croce CM, Condorelli G. MicroRNAs as regulators of death receptors signaling. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:200–208. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nowak M, Gaines GC, Rosenberg J, Minter R, Bahjat FR, Rectenwald J, MacKay SL, Edwards CK 3rd, Moldawer LL. LPS-induced liver injury in D-galactosamine-sensitized mice requires secreted TNF-alpha and the TNF-p55 receptor. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;278:R1202–1209. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.5.R1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu R, Zhang H, Wang X, Zhou L, Li H, Deng T, Qu Y, Duan J, Bai M, Ge S, Ning T, Zhang L, Huang D, Ba Y. The miR-24-Bim pathway promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis in pancreatic carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6:43831–43842. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huntzinger E, Izaurralde E. Gene silencing by microRNAs: contributions of translational repression and mRNA decay. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:99–110. doi: 10.1038/nrg2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Concannon CG, Tuffy LP, Weisova P, Bonner HP, Davila D, Bonner C, Devocelle MC, Strasser A, Ward MW, Prehn JH. AMP kinase-mediated activation of the BH3-only protein Bim couples energy depletion to stress-induced apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:83–94. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200909166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaufmann T, Jost PJ, Pellegrini M, Puthalakath H, Gugasyan R, Gerondakis S, Cretney E, Smyth MJ, Silke J, Hakem R, Bouillet P, Mak TW, Dixit VM, Strasser A. Fatal hepatitis mediated by tumor necrosis factor TNFalpha requires caspase-8 and involves the BH3-only proteins Bid and Bim. Immunity. 2009;30:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hatano E. Tumor necrosis factor signaling in hepatocyte apoptosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22(Suppl 1):S43–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singhal S, Jain S, Kohaar I, Singla M, Gondal R, Kar P. Apoptotic mechanisms in fulminant hepatic failure: potential therapeutic target. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2009;17:282–285. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e3181906f6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akazawa Y, Cazanave S, Mott JL, Elmi N, Bronk SF, Kohno S, Charlton MR, Gores GJ. Palmitoleate attenuates palmitate-induced Bim and PUMA up-regulation and hepatocyte lipoapoptosis. J Hepatol. 2010;52:586–593. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]