Abstract

Purpose

We aimed to investigate the angiogenic balance in fresh compared to frozen embryo transfers, and among neonates with adverse perinatal outcomes.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study. All IVF cycles resulting in a singleton live birth at a university academic fertility center from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2013, were examined. Concentrations of sFLT-1 and PlGF were measured in previously frozen serum specimens collected during early gestation at approximately 5 weeks gestation. Patients completed an electronic survey to detail perinatal outcome.

Results

We identified 152 singleton live births (103 fresh, 49 frozen). Demographic characteristics were similar between the two groups. Ratios of sFlt-1:PlGF were not different between fresh and frozen transfers. Neonates from fresh cycles had a mean birth weight 202 g lighter (p = 0.01) than frozen cycles, after adjusting for gestational age. Among babies born with poor perinatal outcomes, there was a difference in sFlt-1:PlGF ratios after adjusting for race. In non-Asians, infants born small for gestational age (SGA) (< 10th percentile) had significantly higher sFLT-1:PLGF ratio, median ratio (0.21 vs 0.12, p = 0.016).

Conclusions

Fresh transfers were associated with lower birth weight infants compared to frozen transfers. While there was no difference in sFlt-1:PlGF ratios between fresh and frozen transfers, these ratios were significantly lower in SGA infants, suggesting an imbalance in angiogenic markers during placentation.

Keywords: In vitro fertilization, IVF, Angiogenic markers, Fresh embryo transfers, Frozen embryo transfers, Perinatal outcomes

Introduction

Angiogenesis, the process where new blood vessels develop from pre-existing larger blood vessels, is an important step in establishing a properly functioning placenta [1]. Fetoplacental vasculogenesis starts at day 21 after conception and continues throughout the first trimester to become a richly branched villous capillary bed [2]. Trophoblasts express, and are themselves regulated by, specific angiogenic factors [3]. In particular, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and placental growth factor (PlGF) have been identified as having important roles in promoting neovascularization while soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase (sFlt-1) acts as a growth inhibitory factor [4, 5]. There is an increasing body of literature linking the imbalance of these angiogenic factors (high sFlt-1, low PlGF, high ratio of sFlt-1:PlGF) resulting in an anti-angiogenic state. This dysregulation of angiogenesis contributes to disorders of placental origin such as preeclampsia (PEC), intrauterine growth restriction, and small for gestational age neonates (SGA) [6–9].

Interestingly, serum levels of these angiogenic factors are altered in pregnancies resulting from in vitro fertilization (IVF) compared to pregnancies conceived spontaneously. IVF pregnancies tend to have significantly higher levels of sFlt-1 and lower levels of PlGF throughout gestation [10]. It is also well established that perinatal outcomes in IVF pregnancies are associated with higher complication rates including preeclampsia, pregnancy induced hypertension, intrauterine growth restriction, small for gestational age, placental abruption, and placenta previa [11–13]. The specific cause for the observed difference in perinatal outcomes between IVF conceived vs spontaneously conceived pregnancies is unclear. Some experts have suggested that impaired placentation may be the initiating factor for the subsequent poor perinatal outcome [14]. The theory is that during controlled ovarian stimulation in a fresh embryo transfer cycle, the supra-physiologic estrogen level and premature progesterone secretion may result in a non-synchronous uterine environment. This altered hormonal milieu and uterine asynchrony is suspected as the cause for impaired trophoblastic function during placentation [15–17].

In an attempt to create a more physiologic uterine environment, some clinicians have turned to using more frozen embryo transfers (FET) [18]. Growing studies have emphasized lower rates of adverse perinatal outcomes in FETs compared to fresh embryo transfers. A 2011 systematic review demonstrated that neonates from FETs had lower risk of small for gestational age, preterm birth, and placental abruption [14, 19–21]. The altered uterine environment during COH may be avoided in a FET cycle, where the endometrial preparation consists of a combination of estrogen and progesterone supplementation that is designed to mimic the natural cycle. However, there is scarce information regarding the influence of angiogenic factors in fresh and frozen embryo transfers.

Despite increasing literature comparing perinatal and obstetric outcomes between fresh and FET, no study, to our knowledge, has examined angiogenic profiles at time of early placentation. Our primary objective was to elucidate if there is an imbalance in these angiogenic factors between fresh and frozen embryo transfers during the critical early period of placentation. Our secondary objective was aimed to determine if levels of these angiogenic factors were altered among neonates with adverse perinatal outcomes.

Material and methods

All IVF cycles resulting in an autologous singleton live birth at an academic fertility center from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2013, were included. Singletons that were a result of spontaneous or elective reduction after ultrasound documentation of more than one gestational sacs were excluded. Patients that did not have completed 5-week serum, or fresh transfers into recipients that were unstimulated, were also excluded. All subjects were sent an electronic survey to complete detailing obstetric and perinatal outcomes. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Southern California.

Maternal serum levels of sFlt-1 and PlGF were measured in previously frozen serum specimens collected at the estimated gestational age of 5 weeks. Samples were obtained as part of routine care and stored at −70 °C in a repository. Levels of sFlt-1 and PlGF (measured in pg/ml) were determined by Quantikine ELISA immunoassay (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Intra-assay coefficient of variation for control samples is below 11% for both assays. Inter-assay coefficients of variation are <8% for the sFlt-1-1 assay and <9% for the PlGF assay. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA 14.2 (STATACorp, College Station, TX). Sample size was not initially calculated as there was no literature on levels of angiogenic markers during this early time period of placentation. Previous studies have only evaluated these markers during the late first trimester as part of the first trimester screening blood work [8].

Comparisons among groups were performed using the Pearson’s chi-square or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate. Angiogenic ratio was analyzed using Kruskal-Wallis test and presented as medians. A small for gestational age (SGA) variable was created by regressing birth weight on gestational age. SGA was defined as having a standardized residual less than the 10th percentile.

Results

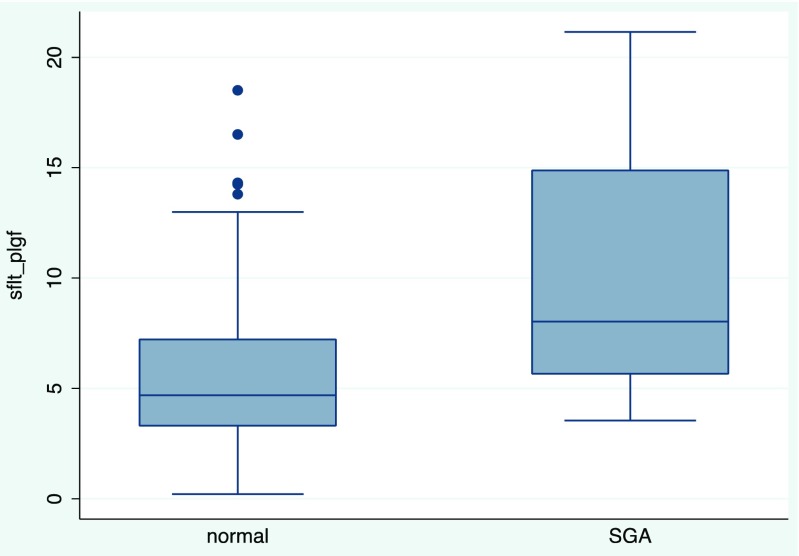

We identified 202 live births during this time period, 35 were multiples and 15 were singletons reduced from multiples, resulting in 152 singleton live births that we analyzed. There were 103 patients in the fresh embryo transfer group and 49 in the FET group. There was no difference between age, BMI, ovarian reserve markers, number of embryos transferred, or number of blastocysts transferred between fresh and frozen embryo transfers (Table 1). There were 136 pregnancies with completed 5-week blood work. Timing from transfer to 5-week blood work was similar between both groups, in 18.3 ± 1.26 days (range 17–25) and 17.7 ± 1.4 days (range 13–20) for fresh and frozen transfers, respectively. Given the small number of patients, eight in each group, there was no further analysis of the patients with missing serum. There was no difference in sFlt-1, PlGF, or the sFlt-1:PlGF ratio between fresh and frozen embryo transfers (Table 2). Neonates from fresh transfers had significantly lower mean birth weight compared to frozen transfers (3198 ± 442 g vs 3400 ± 443 g, p = 0.01) (Table 3). Seventy-four patients completed the electronic survey detailing perinatal outcomes. There was no difference in self-reported rates of obstetric and perinatal complications including hypertensive disease, preeclampsia, placental, or bleeding disorders between fresh and frozen embryo transfers (Table 4). There was one neonatal death in the FET group. The majority of the neonates met growth and developmental milestones; in the fresh embryo transfer group, one neonate had gross motor delay undergoing physical therapy and one neonate had speech delay. Neither the levels of the angiogenic factors nor median sFlt-1:PlGF ratio were different in patients with the presence or absence of various obstetric and/or perinatal complications (Table 5). On evaluation of small for gestational age infants and angiogenic factor levels, there was a significant interaction with race, specifically between Asians and non-Asians (p = 0.009). Due to the statistically significant interaction, we stratified and examined Asian (n = 39) and non-Asian (n = 113) patients separately. In the non-Asian group, infants born with SGA had significantly higher sFlt-1:PlGF ratio compared to infants with normal gestational age weights (median sFlt:PlGF ratio 5.7 vs 4.4, p = 0.015) (Fig. 1, Table 5).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Fresh embryo transfer (n = 103) | Frozen embryo transfer (n = 49) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years)a | 36.2 ± 4.6 | 36.0 ± 4.2 | 0.76 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)a | 24.1 ± 4.7 | 23.8 ± 4.8 | 0.75 |

| Number of embryos transferreda | 2.7 ± 1.1 | 2.5 ± 1.2 | 0.32 |

| Race and ethnicityb | |||

| White | 60 (64) | 34 (36) | 0.03 |

| Asian | 32 (84) | 6 (16) | |

| Other | 11 (55) | 9 (45) | |

aPresented as mean ± SD with t test

bPresented as n (%) with Pearson’s chi-square

Table 2.

Angiogenic factors between fresh and frozen embryo transfers

| Fresh embryo transfer (n = 95)c | Frozen embryo transfer (n = 41)c | p valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| sFlt-1a (pg/ml) | 65.3 (45.4, 83.6) | 69.9 (34.7, 90.7) | 0.88 |

| PlGFa (pg/ml) | 14.3 (11.3, 16.6) | 14.3 (12.0, 18.0) | 0.49 |

| sFlt-1/PlGF | 4.6 (4.1, 7.0) | 4.3 (2.9, 6.8) | 0.66 |

aPresented as median (25th, 75th percentile)

b p values based on Kruskal-Wallis

cOne hundred thirty-six patients with frozen serum

Table 3.

Perinatal outcomes between fresh and frozen embryo transfers

| Fresh embryo transfer (n = 103) | Frozen embryo transfer (n = 49) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birth weighta,b (grams) | 3198 ± 442 | 3400 ± 443 | 0.01 |

| Gestational ageb (weeks) | 38.9 ± 2.3 | 38.5 ± 2.5 | 1.03 |

| Preterm birthc,f | 6 (5.8) | 2 (4.1) | 0.38 |

| Low birth weightd,f | 6 (6) | 1 (2.3) | 0.5 |

| Macrosomiae,f | 1 (1) | 2 (4.1) | 0.24 |

aBirth weight adjusted for gestational age

bPresented as mean ± SD with t test

cPreterm birth defined as delivery prior to 37 weeks of gestation, presented as n (%)

dLow birth weight defined as <2500 g, presented as n (%)

eMacrosomia defined as >4500 g, presented as n (%)

fPresented as Fisher’s exact test

Table 4.

Perinatal outcome survey between fresh and frozen embryo transfer

| Fresh embryo transfer (n = 50)c | Frozen embryo transfer (n = 24)c | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mode of deliveryb | |||

| Cesarean section | 23 (46) | 16 (73) | 0.1 |

| Vaginal delivery | 27 (54) | 8 (33) | |

| Hypertensiona | 7 (14) | 0 (0) | 0.13 |

| Preeclampsiaa | 4 (8) | 1 (4) | 0.9 |

| Placental abruptiona | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 0.82 |

| Placental accretaa | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Retained placentaa | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0 |

| Placenta previaa | 8 (9) | 2 (8) | 0.59 |

| First trimester bleedinga | 7 (14) | 7 (29) | 0.12 |

| Abnormal bleeding during pregnancyb | 13 (26) | 9 (38) | 0.63 |

| NICU admissiona | 9 (22) | 2 (8) | 0.42 |

a p values based on Fisher’s exact test

b p values based on Pearson’s chi-square

cSeventy-four patients completed the electronic survey detailing perinatal outcomes

Table 5.

Median sFlt-1:PlGF ratio in the presence or absence of perinatal complications

| Absent complication | Present complication | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 4.6 (3.3, 7.3) | 5.3 (2.8, 8.0) | 0.77 |

| Preeclampsia | 4.5 (3.1, 7.3) | 5.5 (3.9, 9.4) | 0.62 |

| Placental abruption | 4.5 (3.1, 7.1) | 8.0b (–) | 0.10 |

| Placental accreta | – | – | – |

| Retained placenta | 4.8 (3.2, 7.3) | 4.2b (–) | 0.70 |

| Placenta previa | 4.8 (3.5, 7.4) | 4.1 (1.7, 5.6) | 0.14 |

| First trimester bleeding | 4.8 (3.4, 7.3) | 4.2 (0.4, 7.2) | 0.41 |

| Abnormal bleeding during pregnancy | 4.9 (3.5, 7.4) | 4.1 (2.1, 6.6) | 0.16 |

| Preterm birth | 4.5 (3.0, 6.8) | 4.9 (3.3, 7.8) | 0.50 |

| SGAc | 4.7 (3.3–7.2) | 8.0 (5.7–14.9) | 0.015 |

SGA small for gestational age

sFlt-1:PlGF ratio presented as medians (25th, 75th percentile) with Kruskal-Wallis

bInsufficient numbers to define quartiles

cDue to the statistically significant interaction between race and SGA, we stratified and evaluated only non-Asians (n = 113)

Fig. 1.

Median sFlt-1:PlGF ratio in normal vs small for gestational age neonates (non-Asians)

Discussion

In this study, we found that levels of angiogenic markers, sFlt-1 and PlGF, were not different between fresh and frozen embryo transfer cycles. Although a previous study showed IVF conceived pregnancies had a more anti-angiogenic state compared to spontaneously conceived pregnancies in the second trimester, we did not see a difference in these angiogenic factors when comparing fresh to frozen embryo transfers [10]. Our data suggests that the altered uterine hormonal milieu in fresh embryo transfers does not influence angiogenic factors in early placentation. There is a highly complex and dynamic signaling between trophoblast and the maternal decidua that is critical in establishing a properly functioning placenta [1]. Therefore, there must be many alternate and supplemental pathways that can lead to a successful placentation. It is possible that angiogenic factors do not drive placentation, but is a consequence of other signaling that occurs during placentation. Neither the extent nor the role angiogenic factors play in the earliest stages of placentation is certain.

Among the perinatal complications that we evaluated, only mean birth weight was significantly different between fresh and frozen embryo transfers. Consistent with previous literature, neonates from fresh cycles had a lower mean birth weight, approximately 202 g lighter (p = 0.01) than frozen ETs [19, 20]. While this result is statistically significant, clinical relevance is debatable. There was no difference in the incidence of other poor perinatal outcomes including risk of preterm delivery, macrosomia, hypertensive disorders, placental, or bleeding disorders. This contrasts with the Maheshwari’s systematic review concluding higher rates of multiple complications in fresh embryo transfers [20].

Our secondary objective was to determine if the levels of serum angiogenic factors during early placentation could predict the development of perinatal complications particularly in placentation abnormalities. However, angiogenic factors do not appear to correlate with these outcomes. The only complication was SGA infants in non-Asians who had significantly altered angiogenic markers with a higher anti-angiogenic to angiogenic levels as seen with an elevated sFlt-1:PlGF ratio. This agrees with previous studies that reported increased sFlt-1:PlGF ratio in the late second trimester was associated with SGA at birth [22–25]. Interestingly, our study suggests that an imbalance of angiogenic factors towards an anti-angiogenic state may occur very early, during the initial stages of placentation. More research is needed to determine if these factors influence pregnancy outcomes or if the imbalance of sFlt1:PIGF results from other underlying conditions.

One of the most notable limitations of our study is the small sample size. Because our hypothesis was that angiogenic markers during early placentation may be different between fresh and frozen transfers that result in a live birth, we were very strict with our study population. We limited our evaluation to patients with singleton intrauterine pregnancies resulting in a singleton live birth, to prevent confounding from multiple gestations, spontaneously reduced pregnancies or pregnancies resulting in miscarriages. This small sample size and the further attrition of patients who completed the perinatal outcome survey could have precluded our ability to identify differences in these outcomes that have low prevalence. However, there have been many theories on the etiology of poor placentation seen in fresh IVF cycles as compared to frozen transfers. From our knowledge, evaluating the balance of angiogenic markers between types of transfers have not been reported in the literature previously. Our study goes towards answering one of these important questions which is whether an imbalance in angiogenic factors can be used as markers of dysfunctional placentation. Our study also provides preliminary findings on the correlation of angiogenic markers in other perinatal outcomes including other placentation abnormalities such as placental abruption, placenta accrete, retained placenta, and placenta previa.

In conclusion, the increasing observations of improved pregnancy outcomes found in frozen compared to fresh embryo transfers have spurred researchers to try to better understand the pathophysiology of placentation of IVF embryos. The hypothesis remains that the altered hormonal milieu from controlled ovarian stimulation seen in fresh embryo transfers may contribute to dysfunctional placentation. This is the first study to examine the levels of angiogenic factors between these two groups during the critical stages of early placentation. We found that the angiogenic markers in fact were not significantly different between fresh or frozen embryo transfers. This result adds a unique perspective to the body of literature attempting to unravel the mystery behind defective placentation in IVF. However, whether this imbalance of angiogenic markers is the cause or a result of impaired placentation remains unclear [26]. Future studies are needed to elucidate the uterine environment and mechanisms of impaired placentation in fresh embryo transfers. Understanding the mechanisms that underlie implantation and maternal angiogenesis may ultimately lead to the development of early pregnancy interventions to improve outcomes of fresh and frozen embryo transfers.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the use of the technical support and laboratory facilities of the University of Southern California Reproductive Endocrine Clinical Laboratory at the Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, funded by the USC Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology seed funding.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests and have not received financial support for this work.

References

- 1.Kaufmann P, Mayhew TM, Charnock-Jones DS. Aspects of human fetoplacental vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. II. Changes during normal pregnancy. Placenta. 2004;25(2–3):114–126. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barut F, Barut A, Gun BD, et al. Intrauterine growth restriction and placental angiogenesis. Diagn Pathol. 2010;5:24. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-5-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed A, Perkins J. Angiogenesis and intrauterine growth restriction. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;14(6):981–998. doi: 10.1053/beog.2000.0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wa Law L, Sahota DS, Chan LW, Chen M, Lau TK, Leung TY. Serum placental growth factor and fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 during first trimester in Chinese women with pre-eclampsia—a case-control study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24(6):808–811. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2010.531309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vatten LJ, Asvold BO, Eskild A. Angiogenic factors in maternal circulation and preeclampsia with or without fetal growth restriction. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91(12):1388–1394. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson UD, Olsson MG, Kristensen KH, Akerstrom B, Hansson SR. Review: biochemical markers to predict preeclampsia. Placenta. 2012;33Suppl:S42–S47. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2011.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Espinoza J, Uckele JE, Starr RA, Seubert DE, Espinoza AF, Berry SM. Angiogenic imbalances: the obstetric perspective. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(1):17.e11–17.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.10.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wender-Ozegowska E, Zawiejska A, Iciek R, Brazert J. Concentrations of eNOS, VEGF, ACE and PlGF in maternal blood as predictors of impaired fetal growth in pregnancy complicated by gestational hypertension/preeclampsia. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2015;34(1):17–23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Sanchez O, Llurba E, Marsal G, et al. First trimester serum angiogenic/anti-angiogenic status in twin pregnancies: relationship with assisted reproduction technology. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(2):358–365. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee MS, Cantonwine D, Little SE, et al. Angiogenic markers in pregnancies conceived through in vitro fertilization. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(2):212.e211–212.e218. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinborg A, Loft A, Aaris Henningsen AK, Rasmussen S, Andersen AN. Infant outcome of 957 singletons born after frozen embryo replacement: the Danish National Cohort Study 1995–2006. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(4):1320–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.05.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lancaster PAL. High-incidence of preterm births and early losses in pregnancy after in vitro fertilization. Br Med J. 1985;291(6503):1160–1163. doi: 10.1136/bmj.291.6503.1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang YA, Sullivan EA, Black D, Dean J, Bryant J, Chapman M. Preterm birth and low birth weight after assisted reproductive technology-related pregnancy in Australia between 1996 and 2000. Fertil Steril. 2005;83(6):1650–1658. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roque M, Lattes K, Serra S, et al. Fresh embryo transfer versus frozen embryo transfer in in vitro fertilization cycles: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(1):156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shapiro BS, Daneshmand ST, Garner FC, Aguirre M, Hudson C, Thomas S. Evidence of impaired endometrial receptivity after ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization: a prospective randomized trial comparing fresh and frozen-thawed embryo transfer in normal responders. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(2):344–348. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aflatoonian A, Oskouian H, Ahmadi S, Oskouian L. Can fresh embryo transfers be replaced by cryopreserved-thawed embryo transfers in assisted reproductive cycles? A randomized controlled trial. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2010;27(7):357–363. doi: 10.1007/s10815-010-9412-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 17.Imudia AN, Awonuga AO, Doyle JO, et al. Peak serum estradiol level during controlled ovarian hyperstimulation is associated with increased risk of small for gestational age and preeclampsia in singleton pregnancies after in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(6):1374–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans J, Hannan NJ, Edgell TA, et al. Fresh versus frozen embryo transfer: backing clinical decisions with scientific and clinical evidence. Hum Reprod Update. 2014; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Wennerholm UB, Henningsen AKA, Romundstad LB, et al. Perinatal outcomes of children born after frozen-thawed embryo transfer: a Nordic cohort study from the CoNARTaS group. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(9):2545–2553. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maheshwari A, Kalampokas T, Davidson J, Bhattacharya S. Obstetric and perinatal outcomes in singleton pregnancies resulting from the transfer of blastocyst-stage versus cleavage-stage embryos generated through in vitro fertilization treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(6):1615–1621. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Roque M. Freeze-all policy: is it time for that?. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2015;32(2):171–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Chaiworapongsa T, Romero R, Whitten AE, et al. The use of angiogenic biomarkers in maternal blood to identify which SGA fetuses will require a preterm delivery and mothers who will develop pre-eclampsia. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Lobmaier SM, Figueras F, Mercade I, et al. Angiogenic factors vs Doppler surveillance in the prediction of adverse outcome among late-pregnancy small-for-gestational-age fetuses. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;43(5):533–540. doi: 10.1002/uog.13246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Birdir C, Fryze J, Frolich S, et al. Impact of maternal serum levels of Visfatin, AFP, PAPP-A, sFlt-1 and PlGF at 11–13 weeks gestation on small for gestational age births. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;30(6):629–634. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2016.1182483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sung KU, Roh JA, Eoh KJ, Kim EH. Maternal serum placental growth factor and pregnancy-associated plasma protein A measured in the first trimester as parameters of subsequent pre-eclampsia and small-for-gestational-age infants: a prospective observational study. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2017;60(2):154–162. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2017.60.2.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karumanchi SA, Bdolah Y. Hypoxia and sFlt-1 in preeclampsia: the “chicken-and-egg” question. Endocrinology. 2004;145(11):4835–4837. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]