Abstract

Tonsillectomy is a major surgical procedure in terms of volume in the general otolaryngological practice. It is a 3000-year-old surgical operation, referred in Hindu medicine. There has been a conceptual change in the indications and surgical technique in the last 40 years. A comparative study between the various methods of tonsillectomy was done. The study was carried out in the single institutional set up by the same surgeon but using different techniques. The study aimed at comparing the intra-operative factors (blood loss, time taken for surgery), postoperative results (pain, bleeding, dehydration, time taken for complete healing), and other complications like vomiting and hospitalization time between different groups of surgical methods. This study was done in 2500 patients undergoing tonsillectomy with or without adenoid removal in a period of 35 years (1979–2013). The majority of the patients (approximately 41%) in the first half of this period underwent cold steel tonsillectomy whereas 39% underwent microdebrider assisted tonsillectomy. Microdebrider assisted tonsil surgery was done as day care procedure in 90%. In 21% of the patients, other methods viz coblation, radio frequency and laser were used. Microdebrider intracapsular tonsillectomy is associated with lower mortality and morbidity as compared to cold steel, coblation, electrodissection, laser and radio frequency.

Keywords: Tonsillitis, Tonsillectomy, Adenotonsillectomy, Sleep disordered breathing

Introduction

Tonsillectomy is a 3000-year-old operation. It is one of the major surgical procedure in terms of volume in the general otolaryngological practice. There has been a conceptual change in the indications and surgical technique in the last 40 years. During the past 10 years, there have been a large number of publications in the literature. These publications are a testament to the ongoing growth, development and controversies involved with the subject. Although tonsillectomy is performed less often than it once was, it is still among the most common surgical procedures performed in children anywhere in the world. In 1959, 1.4 million tonsillectomies were performed in the United States. This number had dropped to 260,000 by 1987, when it was the 24th most common indication for hospital admission. The main indication of tonsillectomy in the past used to be recurrent infection. But now the main indication of tonsillectomy has shifted to sleep disturbance.

To compare the rates of major complications, a comparative study between the various methods of tonsillectomy was done. The study was carried out with the same institutional set up and same surgeon but different techniques. The study aimed at comparing the intra-operative factors (blood loss, time taken for surgery), postoperative results (pain, bleeding, dehydration, time taken for complete healing) and other complications like hemorrhage, vomiting and hospitalization time between all groups of surgical methods. This study was done in 2500 patients undergoing tonsillectomy with or without adenoid removal in a period of 35 years (1979–2013).

41% of the patients underwent cold steel tonsillectomy. 39% underwent microdebrider assisted tonsillectomy and in 21% of the patients, other methods like coblation, radio frequency and laser were used. Microdebrider intracapsular tonsillectomy is associated with lower mortality and morbidity as compared to cold steel, coblation, electrodissection, laser and radio frequency. Microdebrider assisted tonsil surgery was done as day care procedure in 90% of cases.

Research on tonsillectomy is still popular. Which is the best method of tonsillectomy with minimum complications? Are perioperative steroids useful and is day care tonsillectomy safe? These are the questions, still to be answered. A study comparing the Cold steel method versus the Soft tissue shaver (microdebrider) was done at the same institution and published by the senior author [42]. Following the study microdebrider became the instrument of choice of the senior author while other methods were also tried keeping in mind the indications and the patients’ wishes.

There are a number of other studies comparing 2 or 3 different methods of tonsillectomy [6, 13, 18, 37]. But we could not find any study in literature comparing the multiple methods of tonsillectomy in one institution and by a single operating surgeon. This prompted us to present this study.

Material and Method

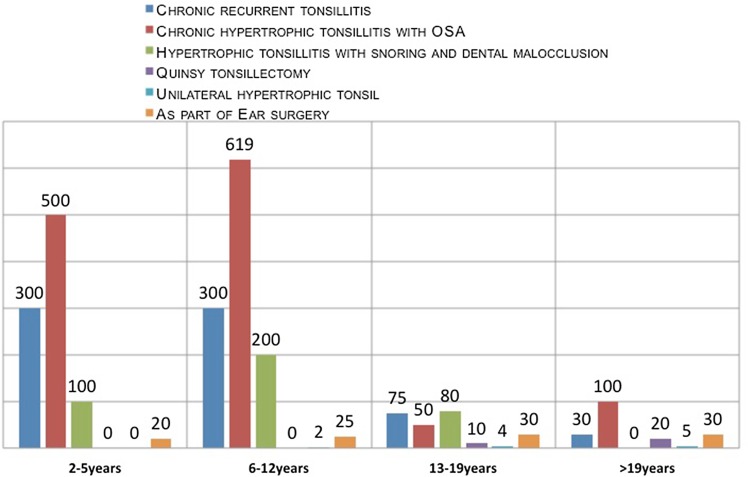

The study was carried out in one institutional set up and by the same surgeon. The study aimed at comparing the intra-operative factors (blood loss, time taken for surgery), postoperative results (pain, bleeding, dehydration, time taken for complete healing) and complications like hemorrhage, vomiting and hospitalization time between all groups of surgical methods. This study was done in 2500 patients undergoing tonsillectomy with or without adenoid removal in a period of 35 years (1979–2013). All selected patients for tonsillectomy had recurrent throat infection and/or sleep disordered breathing causing daytime sleepiness, inattention and poor concentration (Fig. 1). The patients having bleeding diathesis, poor anesthetic risk or uncontrolled medical illness, anemia, acute infection were excluded in this study.

Fig.1.

Indications of tonsillectomy

Laboratory investigations including CBC, BT, CT, ASO titre, CRP were done in all patients undergoing the procedure. Throat swab from the surface of tonsils for culture and sensitivty was done in 120 patients whenever felt necessary especially with chronic tonsillitis not responding to medical treatment. 10 patients out of 120, had a growth of streptococcus. General anesthesia was preferred in all children and most of the adults and LA in those adults who were subjected to LAST and LAUP for OSAS. Boyle’s Davis mouth gag was used in majority in extended neck position.

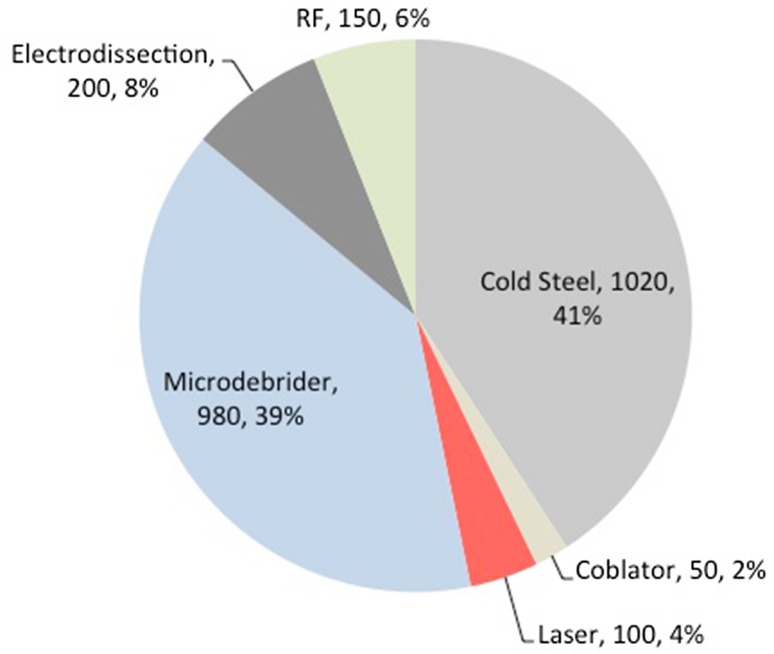

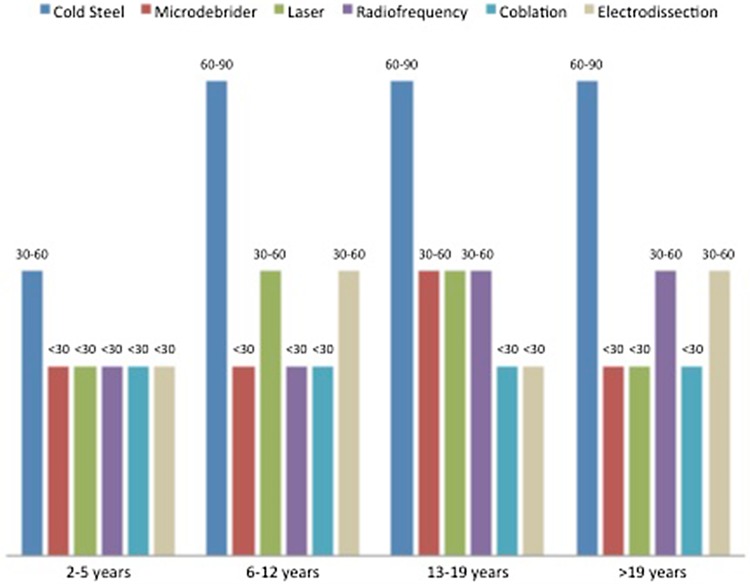

41% of the patients underwent Cold steel tonsillectomy whereas 39% underwent microdebriber assisted tonsillectomy. In 21% of the patients, other methods like coblation, radio frequency and laser were used. Microdebrider assisted tonsil surgery was done as day care procedure in 90% of cases. In the initial phase, cold steel tonsillectomy (Dissection Method) was the only operative procedure. Later on laser, coblation, mono polar/bipolar electrodissection, microdebrider and radio frequency were added to the list (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Surgical techniques

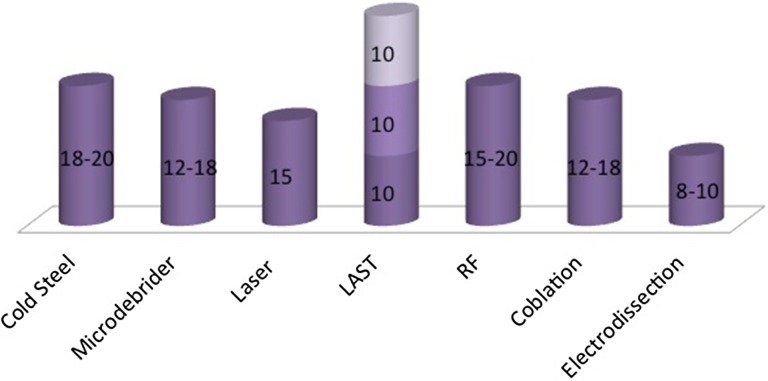

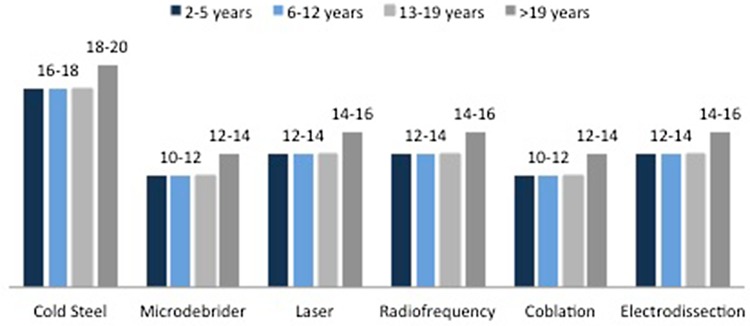

Analgesics were administered during surgery in all except in a control group of 25 patients undergoing partial powered tonsillectomy. Per-operative hydrocortisone injection was administered in all the control group patients. Hydration was maintained in all and patients were encouraged to eat and drink lot of liquids at the earliest in postoperative period. Oral Antibiotics for one week were given to all (Fig. 3). All the patients were evaluated and compared for postoperative pain (Fig. 6), bleeding (Fig. 4), dehydration and recurrence or regrowth of the tonsillar tissue between different techniques in the immediate and late postoperative period. The other postoperative symptoms and signs noted were weight loss, fever, airway obstruction, pulmonary edema, voice changes, Temporo-mandibular joint dysfunction and death. Operative time in minutes was recorded (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Operating time in minutes

Fig. 6.

Post operative pain

Fig. 4.

Per operative bleeding

Results

In this study the indication of tonsillectomy, in majority of patients operated in the first half of the said period was chronic recurrent tonsillitis where as in the second half the indication was hypertrophic tonsillitis with OSA as shown in Fig. 1. Following up on the earlier study comparing cold steel and microdebrider assisted surgery by the same author [41], a retrospective analysis was done which included all the instruments at the author’s disposal. Of the 2500 cases of tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy, 1025 patients were operated with cold steel method in the first half of the period. 39% underwent microdebrider assisted tonsillectomy. In 21% of the patients, other methods like coblation, radio frequency and laser were used (Fig. 2).

The blood loss during surgery was the least with micro-debrider and more with cold steel (Table 4).

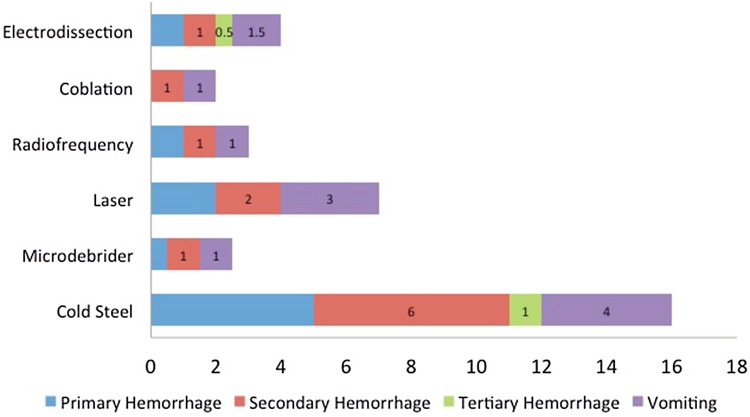

The rate of primary, secondary and tertiary hemorrhage was 5, 6 and 1% respectively with cold steel method. The rate of hemorrhage with microdebrider and coblation were minimum of all methods as shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Complications of tonsillectomy-various techniques

The real operative time was comparable across all methods (Fig. 3). The time taken to control per- operative bleeding was higher with cold steel as compared to others. Pain was found to be minimum in the patients undergoing partial tonsillectomy with coblation and microdebrider (Fig. 6). Both these techniques are just as elegant and just as efficacious. There is lower risk of primary hemorrhage with bipolar as compared to cold steel method but secondary hemorrhage risk increases five times with bipolar electro-dissection (Fig. 5).

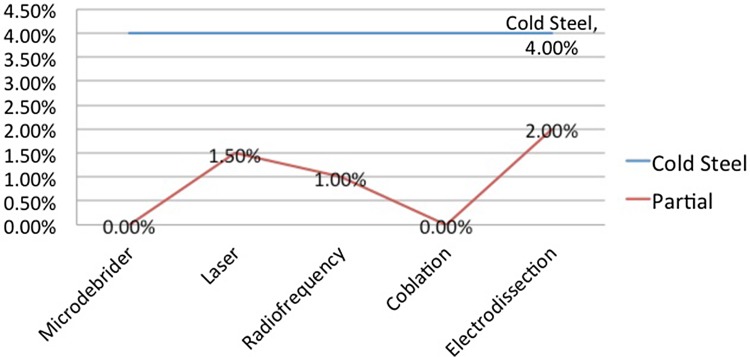

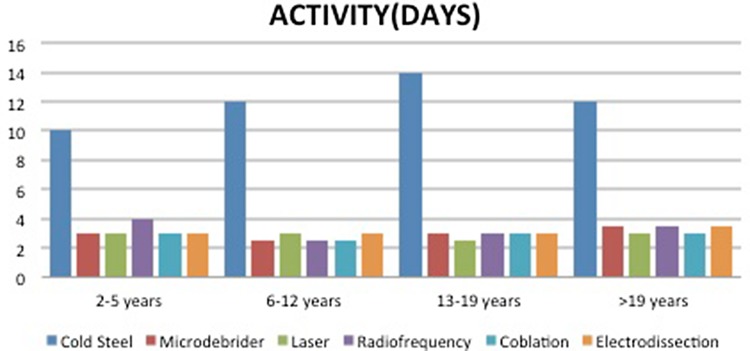

The readmission rate was found to be higher in cases done with cold steel (4%) due to vomiting, bleeding and dehydration (Fig. 7). The patients were back to normal activity within 3 days with partial tonsillectomy but within 10–20 days with total tonsillectomy (Fig. 8). Complete healing of the tonsillar fossa was much early with partial intracapsular tonsillectomy as compared to total or complete (Fig. 6).

Fig. 7.

Return to OT/readmission

Fig. 8.

Return to normal activity (days)

Discussion

Tonsillectomy is being practised for the last 3000 years, with varying popularity over the centuries. The detailed history of tonsillectomy has been well described by Glover [13] in 1918 and McNeill [25] in 1960. The procedure is claimed in some books as “Hindu medicine” about 1000 BC. Others refer to it as cleaning of tonsil using the nail of the index finger. Roughly a millennium later the Roman aristocrat Aulus Cornelius Celsus (25BC-AD50) described a procedure whereby the tonsil was separated from the neighboring tissue with finger or they may be seized by a hook and excised with a scalpel. Galen (AD 121–200) was the first to advocate the use of the surgical instrument known as the snare, a practice that was to become common until Aetius (AD 490) recommended partial removal of the tonsil, writing “Those who extirpate the entire tonsil, remove at the same time, structures that are perfectly healthy, and in this way, give rise to serious hemorrhage”. In the 7th century Paulus Aegineta (AD 625–690) described a detailed procedure for tonsillectomy, including dealing with the inevitable post-operative bleeding. 1200 years passed before the procedure is described again with such precision and detail. The middle ages saw tonsillectomy fall into disfavor. Ambroise Pare (1509) wrote it to be “a bad operation” and suggested a procedure that involved gradual strangulation with a ligature. This method was not popular with the patients due to the immense pain it caused and the infection that usually followed. Scottish physician Peter Lowe, around 1600 AD, summarized the three methods in use at the time, including the snare, the ligature, and the excision. At the time, the function of the tonsils was thought to be to absorb secretions from the nose. It was assumed that removal of large amounts of tonsillar tissue would interfere with the ability to remove these secretions, causing them to accumulate in the larynx, resulting in hoarseness. For this reason, physicians like Dionis (1672) and Lorenz Heister censured the procedure. In 1828, physician Philip Syng Physick modified an existing instrument originally designed by Benjamin Bell for removing the uvula; the instrument, known as the tonsil guillotine (and later as a tonsillotome), became the standard instrument for tonsil removal for over 80 years. Borelli (1860) revived the old method of enucleation as described by Celsus. By 1897, it became more common to perform complete rather than partial removal of the tonsil after American physician Ballenger. He noted that partial removal failed to completely alleviate symptoms in a majority of cases. His results using a technique involving removal of the tonsil with a scalpel and forceps were much better than partial removal. Tonsillectomy using the guillotine eventually fell out of favor in America. George Waugh in 1909 pioneered the dissection tonsillectomy and it ruled the scene for a long time. In mid and late 20th century, the advancement in biomedical instruments and equipments and more understanding of the diseased process, there have been a change in the indications and techniques of tonsillectomy. Haase and Noguera [15] in 1969 introduced diathermy and Goycoolea [14] introduced the concept of suction coagulation in 1982. Pang [28] reported first case of bipolar electrodissection of tonsils in 1995. In late 1960 and early 1970, cryosurgery was used for tonsillectomy, but never gained popurality [19]. Krespi [21] in 1994, introduced the concept of bloodless tonsillectomy with laser. In 1998, Coblation tonsillectomy or cooler ablation was introduced. Powered Soft tissue shavers or microdebrider was used by Koltai [20] in 2002. It was originally developed for microarthroscopy, then used in nasal surgery is now being used for partial tonsillectomy with good results [41]. Harmonic scalpel, electro-dissection, radio-frequency and robotic tonsillectomy has been advocated by various authors with advantages and disadvantages of these techniques. Surgeons find these instruments attractive because they can remove tissue with greater accuracy and precision, great speed, less damage to adjoining tissue and less operative and postoperative complications.

Tonsillitis is caused by Streptococcus or viral agents (Adenoviruses, Influenza, Epstein-Barr, Parainfluenza and Entero viruses). The main symptoms are inflammation and swelling of the tonsils, sometimes severe enough to cause respiratory obstruction. These symptoms are usually accompanied by throat pain, redness or yellow coating on the tonsils. There could be hoarseness, headache, loss of appetite, ear pain, fever, chills and bad breath. Symptoms may also include nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain in children. Tonsillar surgery and its indications and techniques continue to evolve. During the past 10 years, the large number of articles on tonsillar surgery published in the literature is a testament to the ongoing growth, development, and controversies involved with this procedure. Research on tonsillectomy is still popular. Whether an optimal method of tonsillectomy exists, whether peri-operative steroids are useful, and whether outpatient tonsillectomy is safe are still unclear.

The traditional indication for tonsillectomy is recurrent tonsillar infection. There have been a changing trend in the indications of tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy [5, 7, 9, 10 27, 35]. More recently, awareness of the incidence of obstructive adenotonsillar hypertrophy with associated obstructive sleep apnea has increased. In fact, in many practices, it has become the most common indication for tonsillar surgery, especially in younger age group. Infection becomes more important indication as age increases.

30 years ago, approximately 90% of tonsillectomies in children were done for recurrent infection; now it is about 20% for infection and 80% for obstructive sleep-disordered breathing (OSA). Few clinician, these days think sleep disordered breathing is the only absolute indication of tonsillectomy. About the percentage of tonsillectomies for chronic infection versus SDB in pediatric population, it is believed that in children less than 10 years, the ratio of obstruction verses infection is 60:40 and over 10 years it is 75:25. Other relative indications include cranio-facial and dental growth abnormalities, chronic irritation, biopsy for suspicious neoplasms, and halitosis.

Recently, American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation has published clinical practice guidelines: Tonsillectomy in children [4]. The panel made a strong recommendation for: (1) Watchful waiting for recurrent throat infection if there have been fewer than 7 episodes in the past year or fewer than 5 episodes per year in the past 2 years or fewer than 3 episodes per year in the past 3 years; (2) Assessing the child with recurrent throat infection who does not meet criteria in statement 2 for modifying factors that may nonetheless favor tonsillectomy, which may include but are not limited to multiple antibiotic allergy/intolerance, periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis and adenitis, or history of peritonsillar abscess; (3) Asking caregivers of children with sleep-disordered breathing and tonsil hypertrophy about co-morbid conditions that might improve after tonsillectomy, including growth retardation, poor school performance, enuresis, and behavioral problems; (4) Counseling caregivers about tonsillectomy as a means to improve health in children with abnormal polysomnography who also have tonsil hypertrophy and sleep-disordered breathing; (5) Counseling caregivers that sleep-disordered breathing may persist or recur after tonsillectomy and may require further management; (6) Advocating for pain management after tonsillectomy and educating caregivers about the importance of managing and reassessing pain; and (7) Clinicians who perform tonsillectomy should determine their rate of primary and secondary post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage at least annually. The panel on clinical practice guideline on tonsillectomy in children also offered options to recommend tonsillectomy. These options include, recurrent throat infection with a frequency of at least 7 episodes in the past year or at least 5 episodes per year for 2 years or at least 3 episodes per year for 3 years with documentation in the medical record with additional temperature more than 38.3 degree Celcius, cervical adenopathy, tonsillar exudate or positive test for group a Beta hemolytic streptococcus. The degree of benefit in surgically treated children seemed sufficient to justify tonsillectomy in children with throat infection histories [29].

There are number of techniques of tonsillectomy and can be grouped as cold and hot. Cold methods (No heat is used) include dissection, guillotine, partial tonsillectomy with microdebrider, harmonic scalpel, plasma mediated ablation and cryosurgery. Hot methods include electrocautery, laser, coblation and radio-frequency. From guillotine to plasma knife and soft tissue shavers, there is a long list of various techniques with their advantages and disadvantages. Surgeons find these new instruments attractive because they can remove tissue with greater accuracy and less damage to adjacent tissue and, in many cases, they can do so with more speed and ease than is possible with older methods. Because these technologies are relatively new, it is helpful to review how they work.

Technological innovations in any surgical procedure should focus on bloodless surgical field, less operative time, less postoperative pain, improved healing rate, affordability and safety.

Cold steel It ruled the scene for a century and still the most practiced method especially in the developing world. In this method stainless steel scissors and scalpels, toothed forceps and herd’s dissector/retractor are used to dissect the whole tonsil tissue from its capsule. This exposes the underlying constrictor muscles and hence more pain and more chances of hemorrhage per operative and post operatively.

Electro-dissection Mono polar or Bipolar dissection of the whole tonsil. Heat of cautery may reach 300–400 °C to induce hemostasis. It causes more lateral thermal damage and hence more pain and discomfort in the postoperative period. The kinetic energy heats the intracellular and extracellular fluids and ruptures localized tissue cells.

Microscopic tonsillectomy The microscope affords excellent illumination, improved depth perception and detailed view of surgical field. Andrea [1] in a series of 234 patients advocated the use of microscope or surgical loupe and bipolar diathermy to carry out tonsillectomy. It changes the scale of the operation. The planes are dry and easy to follow. It takes extra time to get a dry field. The extra time taken is compensated by avoiding readmission or return to operating room. It is better in adult where there is lot of scarring due to recurrent infections.

Bovie or coblation (cold ablation) or plasma excision Introduced in 1998, it can used to perform total tonsillectomy and partial tonsillectomy. Radio frequency energy is used in a plasma field to break the molecular bonds to excise or dissolve the soft tissue at a temperature of 40–70 degree celsius and hence maintain the integrity of the surrounding tissue. It provides dissection, cautery, suction and hemostasis in the same machine. It is quick, precise and smooth procedure.

Microdebrider or soft tissue shavers 90–95% of tonsillar tissue is removed. A natural biological dressing is left in place over the pharyngeal muscles, preventing injury, inflammation and infection. It cause less pain with rapid recovery and less delayed complications. Partial tonsillectomy for enlarged tonsils and cryptolysis for repeated tonsil infection is suggested. It offers less postoperative pain, a more rapid recovery, a faster return to normal diet and fewer postoperative complications [20, 41].

Laser CO2 laser and KTP lasers can be used. CO2 laser, an excellent cutter, has a valuable role in otolaryngological practice. Tonsillectomy was advocated by Martinez and Akin [24] 1987 and Nishimura et al. [27] in 1988. Krespi [21] introduced LAST (Laser assisted serial tonsillectomy) in 1994. Linder et al. [23] in 1999 advocated the use of laser for tonsillotomy especially in children with large tonsils. LAST, partial and total tonsillectomy can be done with CO2 laser. It causes less bleeding, less pain, discomfort and is a day care procedure. But more secondary hemorrhage and post-operative pain have been noted with laser.

Radio-frequency Cost effective, easy to use and time saving alternative to laser tonsillectomy. Mono polar radio frequency energy is transferred by inserting the probe into the tonsil tissue in three or four sittings. It ultimately produce scarring of the tonsil tissue and thus reduce the size. Quick and smooth, done under light sedation and Local anesthesia, minimum discomfort and usually a daycare procedure. In the cutting and coagulation mode, partial tonsillectomy can be done. It causes less bleeding and less postoperative pain in comparison to cold steel method.

Harmonic scalpel High frequency vibration of the blades leads to hydro-dissection and raising the temperature between 60 and 100° leads to hemostasis. It cause less pain and morbidity.

Transoral robotic radical tonsillectomy It is the latest surgical procedure for the treatment of tumors of tonsil. It is minimally invasive surgery, with excellent exposure, high precision with safety and effectiveness.

Radio frequency thermal ablation Intracapsular and partial volumetric reduction is done using customized probe. It is useful in very young patients where is desirable to leave some functioning lymphoid tissue.

Cryo-tonsillectomy It leads to minimum bleeding, especially useful in patients with bleeding diathesis. Carbon dioxide or liquid nitrogen is used which reduces the temperature to −82 and −196 °C. The main disadvantage of this procedure is more operating time.

What so ever is the method, surgical procedure is associated with morbidity. Morbidity includes hospitalization, risks associated with general anesthesia, prolonged throat pain and financial costs.

There are many studies comparing indications, complications and economics with two or more than two methods of tonsillectomy in literature [3, 11, 12, 16, 36, 39].

The most common complication of tonsillectomy is bleeding, during or after surgery. Despite the surgeon’s most sophisticated efforts to prevent it, hemorrhage remains the most significant complication after tonsillectomy [32]. Windfuhr et al. [42] reported that the rate of primary hemorrhage (within 24 h of surgery) ranged from 0.2 to 2.2% whereas secondary hemorrhage (after 24 h of surgery) ranged from 0.1 o 3%. Johnson [17] described operative complications which include trauma to teeth, larynx, pharyngeal wall/soft palate, difficult intubation, laryngospasm, laryngeal edema, aspiration, respiratory compromise, endotracheal ignition and cardiac arrest. Post-operative complications include nausea, vomiting, pain, dehydration, referred otalgia, pulmonary edema, velopharyngeal insufficiency and nasopharyngeal stenosis. Rare late complications may include vascular injury, subcutaneous emphysema, jugular vein thrombosis, atlanto-axial dislocation/subluxation, taste disorders and persistent neck pain (Eagleton syndrome or stylohyoid syndrome) [22].

Based on data from 1970, mortality rates for tonsillectomy is estimated at between 1 in 16,000 to 1 in 35000 [31]. In a prospective audit report by Royal college from England to North Ireland [35] between July 2003 to September 2004, reported only one death in post-operative period of 33,921 procedures. Airway compromise due to aspiration is the major cause of death.

Repeated episodes of bleeding should be considered as a warning sign of serious post tonsillectomy hemorrhage. Life threatening postoperative hemorrhage is likely to occur as secondary hemorrhage [44]. Pratt and Gallagher [30] reported 37 deaths out of 968.854 adenoid and tonsil operations. Deep wound necrosis, hypoxic brain damage, aspiration, injury to facial, descending palatine, lingual and branches of external and internal carotid arteries were identified. Devastating outcome was noticed in 10 post-tonsillectomy cases. The permanent neurological sequelae included apallic syndrome, horner’s syndrome, seizures and mental retardation and hemi/tetraplegia. Windfuhr et al. [43], suggested strategies that may assist the surgeon to prevent and manage severe bleeding after adenoidectomy and tonsillectomy. Stuck et al. [38] emphasised the need to follow important principals of management and resuscitation of post operative bleeding in tonsillectomy. These principals include immediate transport, maintain respiratory maintanenec and hemodynamics. Avoid mask ventillation and endotracheal intubation in awake patient should be done.

Careful inspection of the nasopharynx and tonsillar regions must be done to look for any visible pulsations. Surgery must be postponed and MRI angiography may be carried out. The management of brisk bleeding include packing, ligation of bleeding vessel and carotid ligation. The patient should be observed inpatient incases of repeated episodes of bleeding. Aspiration and airway-management are the major causes of fatalities. All proven sleep apnoea patients must be kept in ICU under strict observation.

Pain is unpleasant and distressing complex and subjective phenomenon with emotional experience.

The feeling of pain depends upon the pain threshold of the person, damage done and emotional and psychological setup. Mostly emotional and psychological stable patients have high pain threshold levels and hence feel less pain. If the nerve endings are not exposed, vascularity of the nerve ending is maintained, it is likely that the patient will feel less/minimal pain. Pain in children after tonsillectomy is comparatively less than adults. There is more of scar tissue, more injury and hence more pain in adults. There is less scarring of the tonsillar tissue in children. They start early oral feed and there is no spasm of the constrictor muscles and hence less feeling of pain.

Nausea and vomiting postoperatively can be reduced by peroperative administration of dexamethasone. In all the 25 control group patients, injection Dexamethasone was given peroperatively and all demonstrated less pain, vomiting and nausea. Baugh et al. [4], made strong recommendation of single dose of dexamethasone peroperative in children undergoing tonsillectomy and no perioperative antibiotics. Unfortunately, there is no agreement regarding the use steroids in tonsillectomy. Dexamethasone acts as antiemetic and anti inflammatory agent to reduce edema and release of bradykinin, prostaglandin and leukotrienes.

The Children with OSA are more prone to complications like hemorrhage and respiratory distress and aspiration. The operating surgeon can predict postoperative complications by preoperative polysomnography. Low Oxygen level on PSG warrants overnight observation with continuous pulse oxymetry and availability of positive pressure equipment (CPAP/BIPAP).

There is a great debate about the relative advantages of various techniques. Most of the studies published till date recommend intracapsular or partial tonsillectomy [18, 20, 37, 40, 41]. It causes less pain but small risk of tonsil regrowth. Hot tonsillectomy causes more pain postoperatively, but less bleeding peroperatively and less operative time. The equipment involved with various techniques varies in price, although the important cost factor in tonsillectomy is the operating time.

Conclusion

There is a great debate about the merits and demerits of various tonsillectomy methods. The existing literature consistently reports that of all the techniques, the intracapsular partial technique is better in terms of pain, hemorrhage and healing [2]. Koltai [20] undertook three separate studies about the intracapsular tonsillectomy. The results suggested fewer days of recovery, less analgesia, significant reduced pain, lower rate of dehydration and readmission as compared to total tonsillectomy. Koltai thinks that intracapsular tonsillectomy is best done on small children with obstructive sleep-disordered breathing. Schmidt et al. [36], carried out a study to compare the postoperative complications between electro-dissection and PIT by microdebrider in 2944 patients. They found that the rate of delayed hemorrhage was higher in electro-dissection group (3.4%) as compared to intracapsular group (1.1%). In another study by Gallagher et al. [12], the rate of major complication with coblation, electrodissection and microdebrider were 2.8, 3.1 and 0.7% respectively. Krespi [21] introduced LAST-Laser assisted serial tonsillectomy. It being a day care procedure done under local and minimum bleeding.

Tonsil (and adenoid) surgery for sleep disordered breathing (especially OSAS) is extremely beneficial. Everyone doing this surgery can appreciate its efficacy and the improvement the children (and the few adults who need it for that indication ± UPPP) experience. In our experience—the benefit lasts for many years/lifetime and the lingual tonsil hypertrophy happen in the minority of the patients. Does the benefit outweighs the risk? In severe OSAS kids the answer is definite yes. To reduce the risk—tonsillotomy (intracapsular partial tonsillectomy) should be preferred. The life endangering bleeding risk is practically zero.

However, irrespective of the techniques used, the most important issue in tonsillectomy is the postoperative monitoring of the patient. Postoperative early visit by bedside is a must, preferably twice. Failure to recognize postoperative bleeding and securing the airway is the main cause of death. Otolaryngology-trained and experienced nurses are required in the early follow up especially at nights. Any amount of blood in the mouth must be attended immediately. Blood clots are sessile threats in the postoperative period [33].

Special precautions and care should be taken in all proven cases of sleep disordered breathing cases. Don Setliff [8] in a personal communication/discussion, expressed the necessity of utmost care postoperatively. According to him, the patient should have one-to-one nursing coverage in postoperative care unit with the nurse positioned at the head of the bed and listening to to the airway, especially until the reflexes recover. Suction should be at hand, at the head of the bed. Charting takes a distant second importance to monitoring the airway. The mistake sometimes made by nurses is to assume that all patients recover. Even in the absence of bleeding, patients -especially young children whose reflexes have not recovered- can quietly regurgitate the stomach juices and inhale them into the lungs. It needs a great vigilance to prevent such happenings. In India there is no such reported audit till date.

Economics do need to be addressed as well. Cold steel tonsillectomy offers the most economical choice. The regrowth of the tonsillar tissue, especially the lingual, after partial tonsillectomy has to be answered in the time to come. Of all the methods, the authors have found that the Powered intracapsular partial tonsillectomy using microdebrider is the best method followed by coblation as far as per-operative and post operative complications are concerned. If you have something that works, stick with it. Sometimes people make a decision to change just for the sake of change.

Abbreviations

- LAST

Laser assisted serial tonsillectomy

- LAUP

Laser assisted uvulopalatopharygoplasty

- PIT

Powered partial intracapsular tonsillectomy

- OSA

Obstructive sleep apnea

- SDB

Sleep-disordered breathing

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Andrea M. Microsurgical bipolar cautery tonsillectomy. Laryngoscope. 1993;103(10):1177–1178. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199310000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aremu SK (2012) A review of tonsillectomy techniques and technologies. In: Gendeh BS (Ed) Otolaryngol, InTech, ISBN: 978-953-51-0624-1 pp 161–170. www.intechopen.com/books.otolaryngology/a-review-oftonsillectomy-techniques-and-technologies

- 3.Babademez MA, Yurekli MF, Acar B, Gunbey E. Comparison of radiofrequency ablation, laser and coblator techniques in reduction of tonsil size. Acta Otolarygol. 2011;131(7):750–756. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2011.553244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baugh RF, Archer SM, Mitchell RB, Rosenfeld RM, Amin R, Burns JJ, Darrow DH, Giordano T, Litman RS, Li KK, Mannix ME, Schwartz RH, Setzen G, Wald ER, Wall E, Sandberg G, Patel MM. Clinical practice guideline: tonsillectomy in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;144(1S):S1–S30. doi: 10.1177/0194599810389949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bluestone CD. Current indications for tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 1992;155:58–64. doi: 10.1177/00034894921010S112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darrow DH, Siemens C. Indications for tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. Laryngoscope. 2002;112(suppl 100):6–10. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200208001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Densert O, Desai H, Eliasson A, Frederiksen L, Anderson D, Olaison J, Widmark C. Tonsillotomy in children with tonsillar hypertrophy. Acta Otolaryngol. 2001;121(7):854–858. doi: 10.1080/00016480152602339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Don Setliff- discussion on net OTO-HNS group, Medispeciality.com 27 Dec 2013

- 9.Deutsch ES (1996) Tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy Changing indications. Pediatr Otolaryngol Pediatr Clin North Am 43(6). http://www.pediatric.theclinics.com/article/S0031-3955(05)70521-6/fulltext [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Erez Bendet in a personal communication (Discussion) at otohns group dt 27 Dec 2013

- 11.Friedman M, LoSavio P, Ibrahim H, Ramakrishanan V. Radiofrequency tonsil reduction: safety, morbidity and efficacy. Laryngoscope. 2003;113(5):882–887. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200305000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallagher TQ, Wilcox L, McGuire E, Derkay CS. Analysing factors associated with major complications after adenotonsillectomy in 4776 patients: comparing three tonsillectomy techniques. Otolaryngol Head Neck. 2010;142(6):886–892. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glover EEV. Historical account of tonsillectomy. Br Med J. 1918;2(3025):685. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.3025.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goycoolea MV, Cubillos PM, Martinez GC. Tonsillectomy with suction coagulator. Laryngoscope. 1982;92(7):818–819. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198207000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haase FR, Noguera JT. Hemostasis in tonsillectomy by electrocautery. Arch Otolaryngol. 1962;75(2):25–26. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1962.00740040131009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hesham A. Bipolar diathermy versus cold dissection in paediatric tonsillectomy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73(6):793–795. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2008.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson LB, Elluru RG, Myer CM. Complications of adenotonsillectomy. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:35–36. doi: 10.1002/lary.5541121413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnston DR, Gaslin M, Boon M, Pribitkin E, Rosen D. Postoperative complications of powered intracapsular tonsillectomy and monopolar electrocautery tonsillectomy in teen versus adults. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2010;119(7):485–489. doi: 10.1177/000348941011900710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaluskar SK, Krespi J, Remacle M, Kacker A (2014) Laser tonsil surgery section VI. In: Oswal VS et al (eds) Laser tonsil surgery in principles and practice of lasers in otolaryngology and head and neck surgery, 2nd edn, Vol I. Kugler Publications, Amsterdam, pp 651–655

- 20.Koltai PJ, Solares CA, Mascha EJ, Xu M. Intracapsular partial tonsillectomy for tonsil hypertrophy in children. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:17–19. doi: 10.1002/lary.5541121407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krespi YP, Ling EH. Laser-assisted serial tonsillectomy. J Otolaryngol. 1994;23:325–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leong SC, Karkos PD, Papouliakos SM, et al. Unusual complications of tonsillectomy: a systemic review. Am J Otolarygol. 2007;28:419–422. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linder A, Markstrom A, Hultcrantz E. Using the carbon dioxide laser for tonsillotomy in children. Int J Peditr Otolaryngol. 1999;50(1):31–36. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(99)00197-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez SA, Akin DP. Laser tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1987;20(2):371–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mcneill RA. A history of tonsillectomy: two Millenia of trauma, haemorrhage and controversy. Ulster Med J. 1960;29(1):59–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noah PP, David LW. Trends in the indications for pediatric tonsillectomy or adenoidectomy. Int J Ped Otolarygol. 2011;75(2):282–285. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishimura T, Yagisawa M, Suzuki A, Okada T (2009) Laser tonsillectomy. Acta Otolaryngolica (Stockh). 105(suppl 454):313–15. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3109/00016488809125046?journalCode=ioto20#.VoN0nxHUb2Q [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Pang YT. Paediatric tonsillectomy: bipolar electrodissection and dissection/snare compared. J Laryngol Otology. 1995;109(8):733–736. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100131172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paradise JL, Bluestone CD, Colborn DK, Bernard BS, Rockette HE, Kurs-Lasky M. Tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy for recurrent throat infection in moderately affected children. Pediatrics. 2002;110:7–15. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pratt LW, Gallagher RA. Tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy: incidence and mortality 1968–1972. Otolarygol Head Neck Surg. 1979;87:159–166. doi: 10.1177/019459987908700201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Randel A. Paradise criteria for tonsillectomy in children and adolescents; Practice guidelines: AAO–HNS guidelines for tonsillectomy in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(5):566–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Randall DA, Hoffer ME. Complications of tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;118(1):61–68. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(98)70376-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Refik Caylon, Personal communication, Discussion group,OTOHNS(Medispeciality.com) 26 Dec 2013

- 34.Rosenfeld RM, Green RP. Tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy: changing trends. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1990;99:187–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Royal College of Surgeons of England. National prospective tonsillectomy audit: final report of an audit carried out in England and Northern Ireland between July 2003 and September 2004. May 2005. www.entuk.org/members/audit/tonsil/tonsillectomyauditreport_pdf. Accessed February 3, 2010

- 36.Schmidt R, Herzog A, Cook S, O’Reilly R, Deutsch E, Reilly J. Complications of tonsillectomy: a comparison of techniques. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133(9):925–928. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.9.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Solares CA, Koempal JA, Hirose K, Abelson TI, Reilly JS, Cook SP, April MM, Ward RF, Bent JP, 3rd, Xu M, Koltai PJ. Safety and efficacy of powered intracapsular tonsillectomy in children: a multi- center retrospective case series. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69(1):21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stuck BA, Windfuhr JP, Genzwurker H, Schroten H, Tenenbaum T, Gotte K. Tonsillectomy in children. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2008;105(49):852–861. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2008.0852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stucken EZ, Grunstein E, Haddad J, Jr, Modi VK, Waldman EH, Ward RF, Stewart MG, April MM. Factors contributing to cost in partial versus total tonsillectomy. Laryngoscope. 2013;123(11):2868–2872. doi: 10.1002/lary.24025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vaughan AH, Derkey CS. Microdebrider intracapsular tonsillectomy. ORL J Otolaryngol Relat Spec. 2007;69(6):358–363. doi: 10.1159/000108368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verma R (2005) Soft tissue shavers in Adenotonsillectomy. Ind J Otol H N Surg spl issue-II:452–54

- 42.Windfuhr JP, Chen YS, Remmert S. Hemorrhage following tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy in 15218 patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Windfuhr JP, Schloendoff G, Andreas MS, Andreas P, Kremer B. A devastating outcome after adenoidectomy and tonsillectomy: ideas for improved prevention and management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140:191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Windfuhr JP, Schloendorff G, Baburi D, Kremer B. Serious post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage with and without lethal outcome in children and adolescents. Int J Ped Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72(7):1029–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]