Abstract

Dizziness is a common symptom and though most of the causes are benign yet some may be potentially life threatening. Diagnosis can be a challenge sometimes due to lack of dedicated vestibular lab and injudicious use of vestibular suppressant medications. A 2 year retrospective study of the hospital records from September 2014 to August 2016 was done to study the causes of dizziness and the limitations and challenges in the diagnosis. 75 complete records of patients presenting with dizziness were accessed and analysed. 54.7% of the patients were males and most patients were young adults. Most of the cases were benign and Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo was the commonest diagnosed case (20%). Potentially life threatening cases diagnosed were cerebellar infarct and posterior fossa space occupying lesion (5.3%). Complete evaluation of a dizzy patient must be done to arrive at a causal diagnosis. Injudicious use of vestibular sedatives should be discouraged. Proper training and education to the primary care physician should be imparted so that they can adopt a practical approach for evaluation and management of a dizzy person.

Keywords: Dizziness, Peripheral vertigo, Central vertigo, Cervicogenic, Positional, Migraine vestibulopathy, Suppressants, Rehabilitation

Introduction

Dizziness is a common symptom in an ENT clinic and accounts for 25% visits to the emergency department [1]. The causes of dizziness are varied. Most cases are benign but distressing while some may be potentially life threatening. Evaluating a dizzy patient is a challenge for every clinician as very often the patient is too distressed and symptomatic to cooperate with the evaluation process. Rapid alleviation of symptoms is of prime importance for the patient and in the process diagnosis often takes a backstage. The use of vestibular suppressants provide the symptomatic improvement but delay the diagnosis as these drugs mask the peripheral vestibular signs. Lack of dedicated vestibular lab in many health care set up is also a limiting factor in proper diagnosis. The aim of the study is to look into various causes of vertigo and the pitfalls in their diagnosis and management.

Materials and Methods

The study is a retrospective analysis of hospital records of all patients presenting with vertigo or dizziness for the period ranging from September 2014 to August 2016. Children less than 10 years were not included as the spectrum of dizziness in this age group is different from the adult vertigo. Incomplete records were excluded from the study. All the records retrieved were subjected to analysis of the clinical presentation, diagnosis and management. Institutional ethical clearance was obtained before initiating the study and the study design was cleared by the research protocol evaluation committee of the institution.

Results and Observation

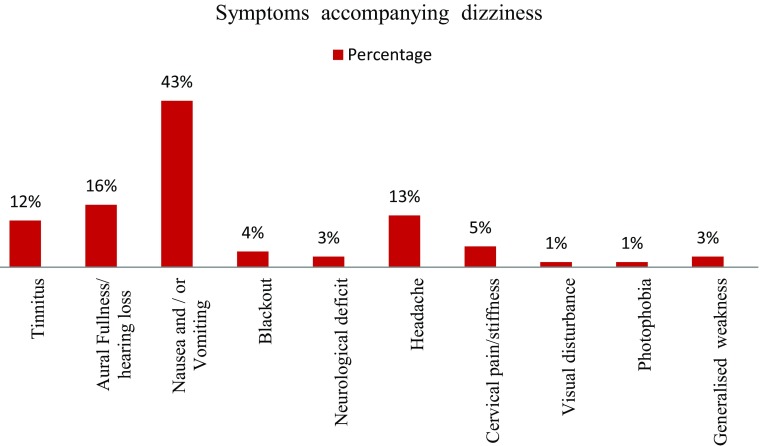

A total of 286 hospital records from September 2014 to August 2016 were accessed which had dizziness or vertigo as the chief complaint or any one of the associated complaints. Only 75 records had complete evaluation of the vertigo/dizziness from which a diagnosis could be made. Of them 24 patients (32%) had presented initially to the Department of ENT of the institute while 51 patients (68%) had received some form of treatment before being referred to the department of ENT. Almost 30% (23 patients) referred had already received some form of vestibular suppressant medications irrespective of the cause of dizziness. 54.7% (41 patients) were males and 45.3% (34 patients) were females. The age wise distribution of the patients are depicted in Table 1. The description of dizziness varied from patient to patient and most patients (50.7%, 38 patients) described their dizzy episode as a ‘spinning motion’ while 33 patients (44%) described their dizzy episode as a ‘sense of imbalance during movement’ while 4 patients (5.3%) described it as ‘lightheadedness’. The duration of dizzy period is depicted in Table 2 and the accompanying symptoms associated with dizziness are shown in Fig. 1. The time of presentation after the initial onset of symptoms is shown in Table 3. The clinical diagnosis of the cause of dizziness was varied and the most common diagnosis was Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo 20% (15 cases). The breakup of clinical diagnosis is shown in Table 4. All the cases were managed conservatively with medications or vestibular exercises. One case of posterior fossa space occupying lesion needed neurosurgical intervention but refused treatment.

Table 1.

Age and sex distribution of the patients

| Age group | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| 10–20 years | 1 | 2 |

| 21–40 years | 21 | 20 |

| 41–60 years | 13 | 7 |

| 61–80 years | 6 | 4 |

| > 80 years | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 41 | 34 |

| Percentage | 54.7 | 45.3 |

Table 2.

Table showing the duration of dizzy period

| Duration of dizzy period | No. of patients | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Seconds to few minutes | 18 | 24 |

| More than 20 min but less than 24 h | 13 | 17.3 |

| More than 24 h but less than 1 week | 18 | 24 |

| 1–2 weeks | 8 | 10.7 |

| More than 2 weeks | 13 | 17.3 |

| Not specified | 5 | 6.7 |

Fig. 1.

Chart showing symptoms accompanying dizziness

Table 3.

Table showing time of initial presentation to the OPD/emergency after the onset of dizziness

| Time of presentation to OPD/emergency | No. of patients | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Less than 24 hr | 23 | 30.7 |

| More than 24 hr less than a week | 30 | 40 |

| 1–4 weeks | 11 | 14.7 |

| 1–6 months | 7 | 9.3 |

| More than 6 months | 4 | 5.3 |

Table 4.

Table showing diagnosis of dizziness

| Diagnosis | Male | Female | Total | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPPV | 7 | 8 | 15 | 20 |

| Neuronitis | 0 | 5 | 5 | 6.7 |

| Labyrinthitis | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Eustachian tube dysfunction | 4 | 4 | 8 | 10.7 |

| Meniere’s disease | 4 | 0 | 4 | 5.3 |

| Cholesteatoma with labyrinthine fistula | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1.3 |

| Migranous vertigo | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| SSNHL | 3 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Vestibulopathy of elderly | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Psychogenic | 3 | 3 | 6 | 8 |

| Cardiac | 3 | 3 | 6 | 8 |

| Metabolic | 3 | 2 | 5 | 6.7 |

| Ocular | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Cervicogenic | 3 | 1 | 4 | 5.3 |

| Cerebellar cause | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Posterior fossa SOL | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1.3 |

| Ramsay Hunt syndrome | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2.7 |

| Total | 41 | 34 | 75 | 100 |

BPPV benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, SSHNL sudden sensorineural hearing loss, SOL space occupying lesion

Discussion

Dizziness is common in our practice and an estimated 25% present to the emergency department with acute vestibular syndrome [1]. Approximately 2.2% patients initially consult their physician per year for dizziness [2]. Unlike other studies a slight preponderance of male population was seen in this study [3–5]. Though various studies show an increase in incidence with age, we found 54.7% patients falling in the age group of 21–40 years [4, 5]. The symptom dizziness is often vaguely defined and narrated by patients which may be “confusing” and “discouraging” for the physician [6]. In this study most patients described their dizziness as a spinning motion while others described it as a sense of imbalance. Lightheadedness described by patients is often confused with dizziness though the term has no clear definition or associated diagnosis [6]. Hallucination of rotatory motion (or true vertigo) associated with nausea and vomiting points towards an acute peripheral vestibular disorder. Disequilibrium on the other hand point towards a poorly compensated vestibular disorder, ocular disorder or peripheral neuropathy. Dizziness with blackout is mostly associated with cardiovascular cause and is an important cause in the elderly [6].

The duration of dizzy spell often provide an important clue to diagnosis. Dizziness occurring as a result of an acute vestibular event is usually compensated within few weeks provided there are no factors to impede the process. True vertigo lasting few seconds and aggravated with change of head position are mostly benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) which was the most commonly diagnosed condition in the present study. Most of the time the cause of acute vertigo is benign and may include Meniere’s disease, vestibular neuronitis, labyrinthitis or labyrinthine fistula etc. However at times it may be due to underlying serious condition. It has been seen that cerebellar infarction or brainstem infarction often mimick acute peripheral vertigo and comprises of 2.8% cases presenting with vertigo [7]. An episode of dizziness may precede a delayed neurological event in such cases and it has been reported that approximately 0.93% of individuals discharged with a diagnosis of vertigo in the emergency department developed a major vascular event within the next 180 days [7, 8]. Halmayagi head thrust test can clinically differentiate vestibular neuritis from cerebellar or brainstem infarction but practically in our experience it is often difficult to perform the test in presence of an acute vertigo [9, 10]. In our study one case of cerebellar infarction and a case of posterior fossa space occupying lesion presented with features of vestibular neuritis and were diagnosed after radiological examination. Diagnosis of cerebellar infarct presenting as an acute vestibular crisis is often missed or delayed. Pitfall leading to misdiagnosis is often due to failure to realize that young patients without traditional vascular risk factors can have vertebro-basilar insufficiency and stroke [11]. A normal CT scan of the brain may fail to identify the initial infarct in almost half the cases and as such an MRI with diffusion weighted image is indicated to rule out early infarct [10, 11].

The association of dizziness with middle ear pressure is known and is commonly seen in scuba divers. Changes in middle ear pressure has been shown to alter the activity of the vestibular neuron by causing pressure changes in the oval window and the round window membrane [12]. 10% of the patients with dizziness had Eustachian tube dysfunction on tympanometry in the present study. It is however not known whether any anatomical abnormality of the oval window or round window membrane precipitated vertigo in these patients. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss may be associated with vestibular symptoms in up to 30% of patients and require detailed audiovestibular, serological and radiological evaluation [13].

Dizziness is a frequent complaint among the elderly patients. In patients older than 70 years approximately 36% females and 29% males have balance disorder. It is important to note that BPPV is often underdiagnosed in this age group and should be ruled out [14]. Vestibular migraine or migraine related vestibulopathy or migranous vertigo is still an underdiagnosed entity because of lack laboratory markers and specific imaging criteria [15]. The diagnosis may be confused at times because about 30% of adult vestibular migraine do not have associated headache [16]. The three cases diagnosed as migranous vertigo had an association with headache and a negative radiological evaluation which helped in arriving at the diagnosis.

Dizziness is a commonly associated symptom in patients of generalized anxiety disorder and major depression [17, 18]. Lehmann et al. [19] in their study found almost 19% of their patients with non organic dizziness and about 42% of patients with vestibular paroxysmia or vestibular migraine had “current psychiatric comorbidiy”. The diagnosis of underlying psychiatric disorder has to be considered when there is a mismatch between the objective evidence of vestibular and neurological dysfunction and the degree of handicap experienced by the patient.

Various cardiological disorders like cardiac arrhythmias, myocardial infarction and angina may manifest as dizziness in the patients. However this is often associated with ‘blackout’ [20]. Postural hypotension is an important cause among the elderly patients and those with autonomic dysfunction and has to be excluded [21]. Cervicogenic vertigo is a controversial entity and various theories have been proposed regarding its pathophysiology [22]. The cases diagnosed with cervicogenic vertigo in the present study had cervical pain and stiffness associated with vertigo and other possible causes were ruled out by audiovestibular and radiological tests. Metabolic and endocrine abnormalities are important cause of dizziness and need to be excluded in patient presenting with dizziness. Thyroid dysfunction more commonly hypothyroidism has been diagnosed in almost 10% of cases of sudden onset dizziness [23–25]. The association of dizziness with refractive error or visual abnormality was reviewed by Armstrong et al. [26] and a positive correlation was found. In our study three patients with dizziness had refractive error which when corrected resulted in the amelioration of the symptom of dizziness. Similar result was also obtained by Supuk et al. [27] where dizziness improved after routine cataract surgery.

The causal diagnosis of dizziness remain elusive in 22% of the cases presenting in an emergency department [1]. The diagnosis of dizziness require detailed vestibular evaluation which may include video nystagmography, cervical and ocular vestibular evoked myogenic potential (VEMP) and rotatory testing to arrive at a causal diagnosis. Unfortunately such sophisticated equipments are not available in many health care setup and the clinician has to rely on the clinical judgment and radiological evaluation to clinch the diagnosis.

It is seen that many primary health care providers primarily seek to ameliorate symptom of dizziness. In the present study almost 30% of the patients referred from peripheral health care set up were empirically treated with vestibular suppressants regardless of the cause of dizziness. Often BPPV and acute vestibulopathy are managed in the emergency on similar lines even though the pathology of the entities are different [5]. It has been observed that vestibular suppressant is given to BPPV patients (approx 58% cases) and to those with acute vestibulopathy (approximately 78%). The same drug is also used in patients with symptomatic dizziness without establishing the cause of the dizziness [5]. Such practice has to be discouraged as prolonged use of CNS or vestibular sedatives delay vestibular compensation which is detrimental for the rehabilitation of the patient [28–30].

Conclusion

Evaluation of a dizzy patient is a challenge due to the wide spectrum of the condition and lack of sophisticated equipments in a peripheral set up. Though the symptom may be poorly described by the patient yet it is of outmost importance to carry out methodical clinical examination. Prompt referral to the specialist should be done instead of resorting to injudicious use of vestibular suppressants. It is also imperative to impart necessary training and education to the primary care physicians so that they can adopt a practical approach in evaluation and management of dizziness. It is also recommended that a patient with acute vestibular event be observed for delayed onset of any neurological event.

Summary:

Dizziness is a common complaint the causes of which are varied.

Most of the causes of dizziness are benign and self limiting.

Conditions like cerebellar and brainstem infarction may mimick peripheral vertigo and are sometimes missed if one is not aware of them.

A patient with acute vestibular event should be observed for delayed onset of any neurological symptoms.

Diagnosis and evaluation of a dizzy patient may require sophisticated audiovestibular setup which is not available in all settings.

Injudicious use of vestibular suppressants should be discouraged as they delay the diagnosis and prevent vestibular rehabilitation by compensatory mechanism.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study has been approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee (REF NO: SMIMS/IEC/C/2016-35 dated 25.06.2016). The study is a retrospective analysis of hospital records and as such individual consent was not obtained. There are no direct or indirect identifiers in the study.

Contributor Information

Soumyajit Das, Email: drsoumya_entamch@rediffmail.com.

Suvamoy Chakraborty, Email: drsuvamoy@rediffmail.com.

Sridutt Shekar, Email: sriduttshekar@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Tarnutzer AA, Berkowitz AL, Robinson KA, Hsieh YH, DE Toker N. Does my dizzy patient have a stroke? A systematic review of bedside diagnosis in acute vestibular syndrome. CMAJ. 2011;183(9):E571–E592. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bird JC, Beynon GJ, Prevost AT, Baguley DM. An analysis of referral patterns for dizziness in the primary care setting. Br J Gen Pract. 1998;48(437):1828–1832. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sen K, Sarkar A, Raghavan A. The vertigo spectrum: a retrospective analysis in 149 walk-in patients at a specialised neurotology clinic. Astrocyte. 2016;3:12–14. doi: 10.4103/2349-0977.192706. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teggi R, Manfrin M, Balzanelli C, Gatti O, Mura F, Quaglieri S, Bussi M. Point prevalence of vertigo and dizziness in a sample of 2672 subjects and correlation with headaches. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2016;36(3):215–219. doi: 10.14639/0392-100X-847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toker DEN, Camargo CA, Hsieh YH, Pelletier AJ, Edlow JA. Disconnect between charted vestibular diagnoses and emergency department management decisions: a cross-sectional analysis from a nationally representative sample. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:970–977. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanley K, Dowd TO, Considine N. A systematic review of vertigo in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51:666–671. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casani AP, Dallan I, Cerchiai N, Lenzi R, Cosottini M, Sellari-Franceschini S. Cerebellar infarctions mimicking acute peripheral vertigo: How to avoid misdiagnosis? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148(3):475–481. doi: 10.1177/0194599812472614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim AS, Fullerton HJ, Johnston SC. Risk of vascular events in emergency department patients discharged home with diagnosis of dizziness or vertigo. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57(1):34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.06.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wuyts F. Principle of the head impulse (thrust) test or Halmagyi head thrust test (HHTT) B-ENT. 2008;4(Suppl. 8):23–25. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee H, Sohn SI, Cho YW, et al. Cerebellar infarction presenting isolated vertigo frequency and vascular topographical pattern. Neurology. 2006;67:1178–1183. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000238500.02302.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Savitz SI, Caplan LR, Edlow JA. Pitfalls in the diagnosis of cerebellar infarction. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:63–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2007.tb00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki M, Kitano H, Yazawa Y, Kitajima K. Involvement of round and oval windows in the vestibular response to pressure changes in the middle ear of guinea pigs. Acta Otolaryngol. 1998;118(5):712–716. doi: 10.1080/00016489850183232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schreiber BE, Agrup C, Haaskard DO, Luxon LM. Sudden sensorinural hearing loss. Lancet. 2010;375:1203–1211. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furman JM, Raz Y, Whitney SL. Geriatric vestibulopathy assessment and management. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;18(5):386–391. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e32833ce5a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Ombergen A, Van Rompaey V, Van de Heyning P, Wuyts F. Vestibular migraine in an otolaryngology clinic: prevalence, associated symptoms, and prophylactic medication effectiveness. Otol Neurotol. 2015;36(1):133–138. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langhagen T, Schroeder AS, Rettinger N, Borggraefe I, Jahn K. Migraine-related vertigo and somatoform vertigo frequently occur in children and are often associated. Neuropediatrics. 2013;44:55–58. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1337697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eagger S, Luxon LM, Davies RA, Coelho A, Ron MA. Psychiatric morbidity in patients with peripheral vestibular disorder: a clinical and neuro-otological study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 1992;55:383–387. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.55.5.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroenke K, Lucas CA, Rosenberg ML, et al. Causes of persistent dizziness: a prospective study of 100 patients in ambulatory care. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117(11):898–904. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-11-898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lahmann C, Henningsen P, Brandt T, Strupp M, Jahn K, Dieterich M, Henn AE, Feuerecker R, Dinkel A, Schmidt G. Psychiatric comorbidity and psychosocial impairment among patients with vertigo and dizziness. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 2015;86(3):302–308. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-307601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newman-Toker DE, Hsieh YH, Camargo CA, Pelletier AJ, Butchy GT, Edlow JA. Spectrum of dizziness visits to US emergency departments: cross-sectional analysis from a nationally representative sample. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(7):765–775. doi: 10.4065/83.7.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi JH, Seo JD, Kim MJ, Choi BY, Choi YR, Cho BM, Kim JS, Choi KD. Vertigo and nystagmus in orthostatic hypotension. Eur J Neurol. 2015;22(4):648–655. doi: 10.1111/ene.12622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Peng B. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of cervical vertigo. Pain Physician. 2015;18(4):E583–E595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lok U, Hatipoglu S, Gulacti U, Arpaci A, Aktas N, Borta T. The Role of thyroid and parathyroid metabolism disorders in the etiology of sudden onset dizziness. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:2689–2694. doi: 10.12659/MSM.891305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albernaz PL. Hearing loss, dizziness, and carbohydrate metabolism. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;20(03):261–270. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1558450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen JJ, Chang HF, Chen DL. Recurrent episodic vertigo secondary to hyponatremic encephalopathy from water intoxication. Neurosciences. 2014;19(4):328–330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armstrong D, Charlesworth E, Alderson AJ, Elliott DB. Is there a link between dizziness and vision? A systematic review. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2016;36(4):477–486. doi: 10.1111/opo.12299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Supuk E, Alderson A, Davey CJ, Green C, Litvin N, Scally AJ, Elliott DB. Dizziness, but not falls rate, improves after routine cataract surgery: the role of refractive and spectacle changes. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2016;36(2):183–190. doi: 10.1111/opo.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bamiou DE, Luxon LM. Vertigo: clinical management and rehabilitation. In: Gleeson M, editor. Scott’s Brown otorhinolaryngology, head and neck surgery. 7. London: Hodder Arnold; 2008. pp. 3791–3825. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, et al., editors. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 19. New York: McGraw Hill; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bronstein AM, Lempert TH. Management of the patient with chronic dizziness. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2010;28(1):83–90. doi: 10.3233/RNN-2010-0530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]