Abstract

Ornamental tattooing involves the administration of exogenous pigments into the skin to create a permanent design. Our case focuses on a 62-year-old woman who presented with an inflamed enlarging nodule on her right proximal calf, which arose within the red pigment of an ornamental tattoo. The nodule was diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and subsequently excised. Over the course of the following year, the patient was diagnosed with a total of five additional SCCs that also arose within the red pigment of the tattoo. The increased popularity of tattooing and the lack of industry safety standards for tattoo ink production, especially metal-laden red pigments, may lead to more cases of skin cancer arising within tattoos among patients of all ages.

Case report

A 62-year-old otherwise healthy woman presented with a 1-year history of an inflamed enlarging growth on her right proximal calf, arising within the red pigment of an ornamental tattoo. Her dermatologic history is significant for multiple actinic keratoses and blistering sunburns, but there was no history of skin malignancy.

A physical examination revealed an erythematous tender nodule with hyperkeratotic scale located on the right proximal calf within the inferior lower border of the tattoo (Fig. 1). No popliteal or inguinal lymphadenopathy was palpable.

Fig. 1.

Initial shave biopsy of erythematous tender nodule with hyperkeratotic scale located on the right proximal calf within the inferior lower border of the tattoo.

A shave biopsy was performed, and a histological analysis of the tissue demonstrated pleomorphic squamous keratinocytes with prominent intercellular bridges and dyskeratotic cells arising in the epidermis with irregular extensions into the upper dermis with an overall depth measuring less than 2 mm, most consistent with an invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC; Fig. 2A and B). Exogenous pigment deposition was noted throughout the dermis, consistent with the tattoo. Due to the tumor location, Mohs surgery was elected as the best option for complete resection with concurrent tattoo preservation. The SCC was extirpated with Mohs micrographic surgery, and the resultant defect was closed with a complex repair. (See Fig. 3).

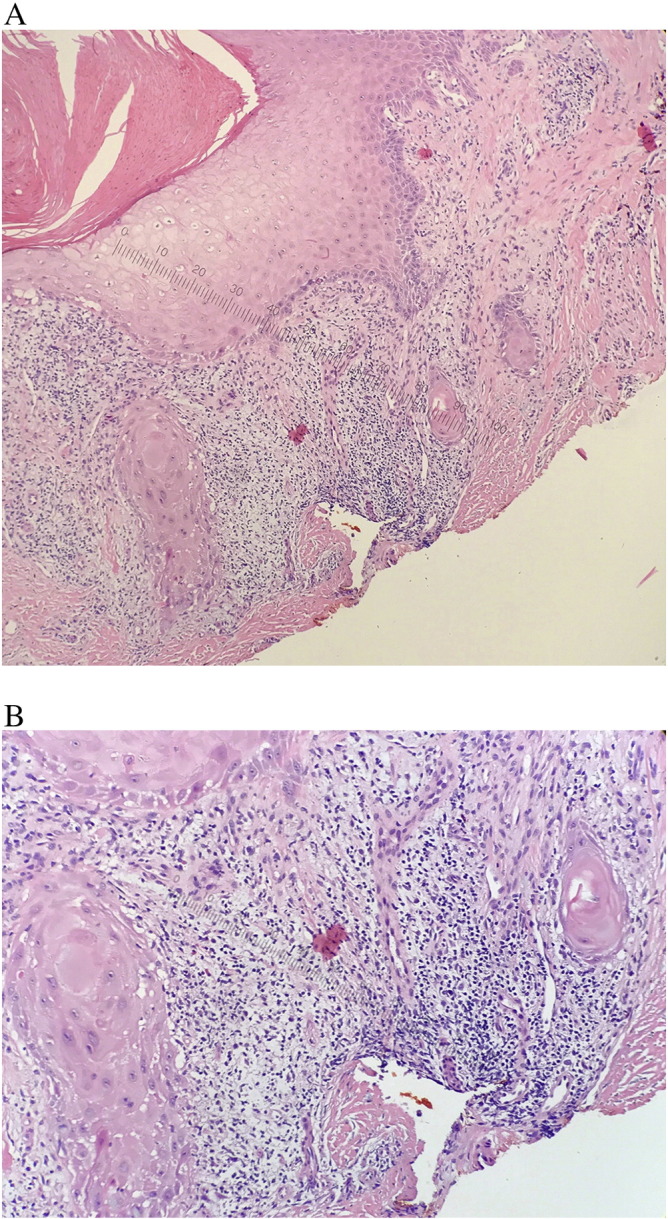

Fig. 2.

(A and B) Hematoxylin and eosin stain of a biopsy of right proximal calf. Magnification × 10, (A), × 40 (B) mildly pleomorphic squamous keratinocytes with prominent intercellular bridges and dyskeratotic cells, consistent with invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

Fig. 3.

Second keratoacanthoma separate from the previous tumor on the right calf, also arising within the red tattoo pigment.

Three months later, the patient returned with a new growth located proximal and discontiguous to the previous tumor on the right calf, also arising within the red tattoo pigment (Fig. 4). She noted that the nodule was inflamed and painful and had been present for the past month. A biopsy of the lesion was consistent with a squamous cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma type. The patient underwent wide local excision with clear histologic margins, and the defect was repaired with a primary closure. Over the course of the following year, the patient presented with two additional separate SCCs lateral to the original tumor. The tumors were treated with wide local excision, each time obtaining clear histologic margins. A fifth biopsy-proven squamous cell carcinoma was identified with the same histological features as the original tumors (Fig. 5). The patient then was referred to a plastic surgeon for complete tattoo excision with split thickness skin grafting.

Fig. 4.

Fifth squamous cell carcinoma arising from red tattoo pigment.

Discussion

Ornamental tattooing involves the administration of exogenous pigment into the dermis, which results in a permanent design. As the incidence of tattooing increases, especially among teenagers, cutaneous reactions to the organic dyes and metals are more frequently encountered (Kluger and Koljonen, 2012). Overall, the risk of adverse outcomes with tattoos is reported to be as high as 20%, which amounts to more than 50 million people (Haugh et al., 2015, Tammaro et al., 2016). The colorful pigment of tattoos is often composed of azo dyes, which are commonly used in consumer product staining (Wenzel et al., 2013). Currently, the production and administration of tattoo inks and pigments in the United States is not regulated, and there are no national guidelines or issued standards (Haugh et al., 2015). Multiple adverse reactions to tattoo pigments, especially red pigment, have been described in the literature. Tattoo-related infections can range from acute pyogenic infections to tuberculosis and are sometimes encountered decades after the initial application (Simunovic and Shinohara, 2014.

Among the different pigments used, red tattoo pigments are thought to contain potentially toxic metals such as cadmium, mercury, and aluminum compounds, which may lead to a higher incidence of adverse reactions such as lichenoid and allergic contact dermatitis (Forbat and Al-Niaimi, 2016, Garcovich et al., 2012, Simunovic and Shinohara, 2014, Sowden et al., 1999). Although less frequently encountered, non-melanoma skin cancers such as SCCs that arise from the red pigment of tattoos have also been reported (Kluger et al., 2008, Paprottka et al., 2014, Sherif et al., 2016, Vitiello et al., 2010). The first report of SCC arising within the red pigment of a tattoo was by McQuarrie, 1966, and more than 23 cases of SCC and keratoacanthoma skin cancers in red tattoo pigment have been reported (Kluger and Koljonen, 2012, McQuarrie, 1966). Despite multiple reports of single tumors within tattoos, there is little evidence of multiple tumors arising from red tattoo pigment in the literature.

There are two proposed mechanisms for SCC within tattoos. The first is that the traumatic skin puncture process of creating a tattoo combined with the body’s ongoing inflammatory response in an attempt to degrade the foreign material (Kluger et al., 2011). Trauma-induced cases occur rapidly, usually within 1 year after the tattooing procedure. The second theory is chronic ultraviolet sun exposure due to tattoo locations on UV-exposed areas (Kluger et al., 2011). A national data set of tattoos in the United States shows that the most common locations for tattoos are the arms and ankles, and the majority of respondents had at least one exposed tattoo (Laumann and Derick, 2006).

The pathogenesis of SCC arising specifically in the red pigment of the tattoo is unknown. A review of the literature found that most of the reported cases of melanoma and basal cell carcinoma occurred on black and darkly colored tattoos while SCCs and keratoacanthomas arose primarily within the red pigment of tattoos (Kluger and Koljonen, 2012). The exogenous tattoo pigments located within the dermis are often phagocytosed by macrophages, which carry the pigments into lymphatics and regional lymph nodes (Jacob, 2002). For this reason, sentinel lymph node biopsies in individuals with tattoos may mimic the appearance of metastatic melanoma (Kluger and Koljonen, 2012).

Treatment of a suspicious lesion within a tattoo should begin with a full thickness skin biopsy. If the biopsy shows evidence of malignancy, a complete surgical excision should be performed. Currently, the treatment modality with the highest cure rate and lowest recurrence rate for SCC is wide local excision (Barton et al., 2015). The increased popularity of tattooing and the lack of safe industry standards for tattoo ink production, especially metal-laden red pigments, may lead to more cases of skin cancer arising within tattoos among patients of all ages.

References

- Barton D.T., Karagas M.R., Samie F.H. Eruptive squamous cell carcinomas of the keratoacanthoma type arising in a cosmetic lip tattoo. Dermatol Surg. 2015;4:1190–1193. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbat E., Al-Niaimi F. Patterns of reactions to red pigment tattoo and treatment methods. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2016;6:13–23. doi: 10.1007/s13555-016-0104-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcovich S., Carbone T., Avitabile S., Nasorri F., Fucci N., Cavani A. Lichenoid red tattoo reaction: Histological and immunological perspectives. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:93–96. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2011.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugh I.M., Laumann S.L., Laumann A.E. Regulation of tattoo ink production and the tattoo business in the US. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2015;48:248–252. doi: 10.1159/000369231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob C.I. Tattoo-associated dermatoses: A case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:962–965. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.02066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluger N., Koljonen V. Tattoos, inks, and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:161–168. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70340-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluger N., Minier-Thoumin C., Plantier F. Keratoacanthoma occurring within the red dye of a tattoo. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:504–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluger N., Plantier F., Moguelet P., Fraitag S. Tattoos: natural history and histopathology of cutaneous reactions. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2011;138:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2010.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann A.E., Derick A.J. Tattoos and body piercings in the United States: A national data set. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:413–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuarrie D.G. Squamous-cell carcinoma arising in a tattoo. Minn Med. 1966;49:799–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paprottka F.J., Bontikous S., Lohmeyer J.A., Hebebrand D. Squamous-cell carcinoma arises in red parts of multicolored tattoo within months. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2014;2:114. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000000055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherif S., Blakeway E., Fenn C., German A., Laws P. A case of squamous cell carcinoma developing within a red-ink tattoo. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;21:61–63. doi: 10.1177/1203475416661311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simunovic C., Shinohara M.M. Complications of decorative tattoos: Recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:525–536. doi: 10.1007/s40257-014-0100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowden J.M., Byrne J.P., Smith A.G., Hiley C., Suarez V., Wagner B. Red tattoo reactions: X-ray microanalysis and patch-test studies. Br J Dermatol. 1999;124:576–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1991.tb04954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tammaro A., Toniolo C., Giulianelli V., Serafini M., Persechino S. Chemical research on red pigments after adverse reactions to tattoo. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;48:46–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitiello M., Echeverria B., Romanelli P., Abuchar A., Kerdel F. Multiple eruptive keratoacanthomas arising in a tattoo. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:54–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel S.M., Rittmann I., Landthaler M., Bäumler W. Adverse reactions after tattooing: Review of the literature and comparison to results of a survey. Dermatology. 2013;226:138–147. doi: 10.1159/000346943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]