Abstract

Cholemic or bile cast nephropathy is an under-reported entity characterized by acute renal dysfunction in patients with hepatic insult. Limited literature is available regarding its clinical presentation, pathogenesis and prognosis. We hereby present a pediatric case who presented with acute on chronic liver failure with renal dysfunction secondary to cholemic nephropathy.

Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; ACLF, acute on chronic liver failure; GCS, Glasgow coma scale; HE, Hematoxylin–Eosin

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is frequently seen in patients with end-stage liver disease and acute on chronic liver failure and portends a poor prognosis.1 Cholemic or bile cast nephropathy is a unique form of AKI or acute renal dysfunction occurring in patients with hepatic injury evident in the form of hyperbilirubinemia and is associated with typical findings on renal biopsy showing tubular epithelial injury and intraluminal bile cast formation.2, 3 There is paucity of literature regarding its clinical presentation, pathogenesis and prognosis in world literature even in adult population with hardly any data in children. We hereby present a pediatric case who presented with acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF) with AKI secondary to cholemic nephropathy with fatal outcome.

A 9 year old male child was admitted with initial complaints of fever/loss of appetite/intermittent fever for 7 days followed by onset of jaundice for last 15 days which was progressive, painless, with dark urine without cholestatic features. For last 3 days prior to admission, there was history of increasing abdominal distension with generalized body swelling and decreased urine output progressing to anuria for last 12 h. He later developed increasing irritability with altered behavior for last 1 day along with spontaneous oral and nasal bleeds. There was no h/o cola colored urine, rash, drug intake, recent change in school performance/behavior/handwriting, infectious contact or significant past or family history. He was admitted in intensive care unit in a sick state with evidence of tachycardia, pallor, deep icterus, prolonged capillary refill time, distended abdomen with shifting dullness, poor sensorium (Glasgow coma scale or GCS of E1V2M2 or 5/15), and semi dilated unequal sluggishly reacting pupils. He was admitted with initial working diagnosis of acute liver failure with multiorgan dysfunction-grade 4 hepatic encephalopathy (as per West Haven criteria), raised intra-cranial pressure with pupillary irregularity, coagulopathy with spontaneous bleeds and anuric state. He was initially managed with mechanical ventilation and standard supportive care for liver failure. In view of anuric state with persistent metabolic acidosis (pH as low as 6.9), patient was initiated on hemodialysis after initial stabilization of hemodynamic parameters. But he continued to be in anuric state and required progressively higher ventilatory and inotropic support. Later he developed progressive dilatation of pupils suggestive of worsening intracranial pressure and expired within 18 h of admission. He likely had underlying Wilson's disease as etiology (low serum ceruloplasmin 9 mg/dl with normal range of 20–50 mg/dl, positive Kayser Fleischer ring, Coomb's negative hemolysis, low serum alkaline phosphatase and higher serum aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase ratio >2.2, i.e. 18.5, urinary copper quantification not feasible due to anuria), though mutational analysis could not be done. He later underwent postmortem liver and kidney biopsy after informed parental consent as per institutional protocol. Liver biopsy showed distortion of acinar architecture with presence of regenerative parenchymal nodules surrounded by broad fibrous septae. Portal tract and septa showed mild to moderate mixed inflammation with periportal spillover. The hepatocytes show regenerative changes, ballooning, macrovesicular steatosis, foamy degeneration and minimal cholestasis. Findings suggested evidence of ACLF (Figure 1a and b). Kidney biopsy revealed 32 unremarkable glomeruli with tubules showing bile cast and tubular epithelial injury in the form of lowering of epithelium, vacuolization, and necrotic debris in the lumen. Bile casts were identified by light microscopy and confirmed by two stains (Fouchet's stain and Perl's stain; considered positive if green color on Fouchet's staining and negative on Perl's stain in at least one tubular lumen). Interstitium showed edema. These findings confirmed cholemic nephrosis (Figure 1c).

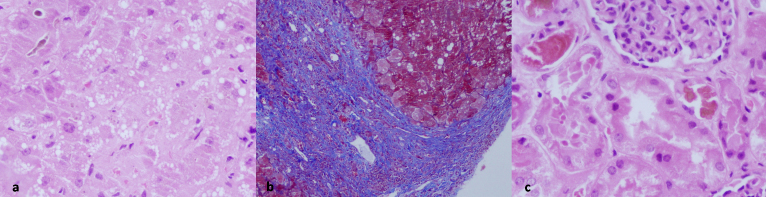

Figure 1.

(a) Liver biopsy shows marked acinar disarray with regenerative 2 cell thick hepatocyte plates, ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes, mixed small and large droplet steatosis, and canalicular bile, evident at upper left corner (400×, Hematoxylin–Eosin/HE). (b) Liver biopsy showing broad curved fibrous septa partially enclosing regenerative hepatic parenchyma. Mixed small and large droplet steatosis is seen in the hepatocytes (200×, Masson trichrome collagen stain). (c) Renal biopsy shows cortex with a part of normal glomerulus and several proximal tubules in the vicinity. These tubules show marked epithelial cell injury with distalisation of tubules, sloughing of cytoplasm into the lumen, flattening of lining epithelium, bile cast in the lumen as well as in a few epithelial cells (400×, HE).

Discussion

We hereby report a pediatric case presenting as liver failure with renal dysfunction secondary to cholemic nephropathy, an under-reported entity with limited literature regarding its clinical presentation, pathogenesis and prognosis.

Though literature is still limited mostly to case reports, cholemic nephropathy has been reported in many disease entities (hepatic or extrahepatic) which lead to hyperbilirubinemia including infections (malaria, infectious mononucleosis), cirrhotic liver diseases (as in the present case), drug related liver injury (anabolic steroids), and post surgery.4, 5, 6, 7 The exact pathophysiology behind this unique entity still remains unknown. Available literature shows that higher the level of serum bilirubin, higher the risk of cholemic nephropathy. As in the present case (with serum bilirubin of 30.9 mg/dl), previous literature has reported cut off level (classically >20 mg/dl) of serum bilirubin levels which predict occurrence of renal injury.3 High bilirubin levels may cause both tubular epithelial cell injury and mechanical injury due to physical tubular obstruction by bile casts.2, 3, 8, 9 But whether it is the deposition of bile casts secondary to hyperbilirubinemia (secondary to any cause) that causes renal injury, or there is primary renal injury due to any insult which leads to deposition of bile casts and further aggravation of renal injury is still not clear. The classical features on renal biopsy include unremarkable glomeruli and evidence of tubular insult in form of presence of pigmented bile casts within the lumen along with dilatation of the lumen and cytoplasmic vacuolization, similar to that in the index case.2, 5 The treatment is usually supportive with treatment aimed at treating the underlying disease causing hyperbilirubinemia along with experimental therapies like plasmapheresis, liver assist devices, etc.2 Prognosis is usually dependent on the severity of underlying disease.

In conclusion, we describe a still under-reported and unrecognized entity of cholemic nephropathy in a pediatric patient with hyperbilirubinemia and liver failure which may be one of the important causes of renal dysfunction in such cases. Renal failure is considered one of the most important prognostic factors in cases with ACLF.10 If underlying pathophysiology can be better understood, it may help in devising strategies for its optimum treatment and good outcome in such cases.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.du Cheyron D., Bouchet B., Parienti J.J. The attributable mortality of acute renal failure in critically ill patients with liver cirrhosis. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:1693–1699. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2842-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel J., Walayat S., Kalva N. Bile cast nephropathy: a case report and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(27):6328–6334. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i27.6328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Betjes M.G., Bajema I. The pathology of jaundice-related renal insufficiency: cholemic nephrosis revisited. J Nephrol. 2006;19:229–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohapatra M.K., Behera A.K., Karua P.C. Urinary bile casts in bile cast nephropathy secondary to severe falciparum malaria. Clin Kidney J. 2016;9(4):644–648. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfw042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bredewold O.W., de Fijter J.W., Rabelink T. A case of mononucleosis infectiosa presenting with cholemic nephrosis. NDT Plus. 2011;4:170–172. doi: 10.1093/ndtplus/sfr038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Slambrouck C.M., Salem F., Meehan S.M. Bile cast nephropathy is a common pathologic finding for kidney injury associated with severe liver dysfunction. Kidney Int. 2013;84(1):192–197. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alkhunaizi A.M., El tigani M.A., Rabah R.S. Acute bile nephropathy secondary to anabolic steroids. Clin Nephrol. 2016;85:121–126. doi: 10.5414/CN108696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fickert P., Krones E., Pollheimer M.J. Bile acids trigger cholemic nephropathy in common bile-duct-ligated mice. Hepatology. 2013;58:2056–2069. doi: 10.1002/hep.26599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bairaktari E., Liamis G., Tsolas O. Partially reversible renal tubular damage in patients with obstructive jaundice. Hepatology. 2001;33:1365–1369. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moreau R., Jalan R., Gines P. Acute-on-chronic liver failure is a distinct syndrome that develops in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(7):1426–1437. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.042. 1437.e1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]