Abstract

Background

End stage liver disease leads to immune dysfunction which predisposes to infection. There has been a rise in antibiotic resistant infections in these patients. There is scanty data f from India or idea regarding the same.

Aim of the study

The present study was undertaken to determine the type of infection acquired and the prevalence of antibiotic resistant infections in cirrhotic patients at a tertiary referral center in South India.

Materials and methods

In this retrospective study, all consecutive cirrhotic patients hospitalized between 2011 and 2013 with a microbiologically-documented infection were enrolled. Details of previous admission and antibiotics if received were noted. In culture positive infections, the source of infection (ascites, skin, respiratory tract: sputum/endotracheal tube aspirate, pleural fluid; urine and blood) and microorganisms isolated and their antibiotic susceptibility was noted.

Results

A total of 92 patients had 240 culture positive samples in the study period. Majority were Klebseilla followed by Escherichia coli and Enterococcus in nosocomial and health care associated infections. However, Enteroccocus was followed by E. coli and Klebsiella in community acquired infections. The antibiotic sensitivity pattern was analyzed for the major causative organisms such as E. coli, Klebsiella and Enterococcus. Most common resistant strains were extended spectrum beta lactamase producing enterobacteriacae (ESBL) followed by carbapenemase producing Klebsiella and methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Conclusion

Noscomial infection is the most common type, with Klebsiella and E. coli and there is significant rise in ESBL producing organism.

Abbreviations: CAI, community-acquired infection; CPK, carbapenemase producing Klebsiella; ESBL, beta lactamase producing enterobacteriacae; ESLD, end stage liver disease; HAI, hospital acquired infection; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; SBP, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; TGC, third generation cephalosporins; UTI, urinary tract infection; VRE, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus

Keywords: antibiotics, microbial resistance, cirrhosis liver

End stage liver disease (ESLD) carries a huge burden for health care worldwide.1 Patients with ESLD have alterations in the immune system and therefore are more susceptible to develop bacterial infection, sepsis, and death.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Infection is either present at admission or develops during hospitalization (nosocomial) in approximately 25–30% of patients.6, 7, 8 Sources of hospital acquired infection (HAI) in ESLD are spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), urinary tract infection (UTI), pneumonia, skin infection with or without bacteremia.2, 3, 4 Almost 80% are due to gram-negative bacilli (GNB) related infections. More recently there has been a steady increase in gram positive cocci infections.7, 8

Rising trend in antibiotic resistant organisms in patients with cirrhosis, especially hospitalized individuals, i.e. nosocomial infection, has been noted.3, 4, 5, 6, 7

The present retrospective study was undertaken to determine the type of infection and the prevalence of antibiotic resistant infections during hospitalization in ESLD patients at a quaternary referral center in South India.

Materials and Methods

In this retrospective study, all hospitalized ESLD patients with microbiologically-documented infection were enrolled. Infections were classified as Community-Acquired Infection (CAI), Healthcare-Associated Infection (HCAI) and nosocomial or Hospital-Acquired Infection (HAI).9, 10

Definitions

Types of Infection

-

a.

Nosocomial infection: Infection acquired 72 h after admission to the hospital.10

-

b.

HCA infection: This group of patients included patients who had infections prior to admission or during within 72 h of hospitalization with history of contact with the hospital setting/health care facility during the last 3 months.9

-

c.

CAI: An infection contracted outside of a health care setting or an infection present at the time of admission

Following details were obtained at the time of admission: age, gender, etiology of cirrhosis, baseline laboratory parameters, details of previous admissions and antibiotics used within or beyond 72 h and indication for admission. All patients routinely had a hemogram, blood and urine culture, ascitic fluid analysis including culture, and an X-ray chest if there were respiratory symptoms.

For blood culture, 10 mL blood samples were collected from 2 different sites in aerobic and anaerobic culture bottles at bedside. For ascitic fluid, 10 mL fluid was inoculated in blood culture bottle. For sputum and endotracheal secretions the sample was collected and processed as per the standard protocol.

Prophylactic antibiotic, piperacillin tazobactam in the scheduled dose (4.5 g three times a day) was given to patients presenting with fever, abdominal pain, skin infection, or those with urinary or respiratory symptoms. Based on the culture sensitivity report the antibiotic was de-escalated or escalated. In culture negative patients, antibiotic was continued for 5 days.

Exclusion criteria: Patients below 18 years of age, those admitted for either transplant workup only or post liver transplant and non-cirrhotic patients.

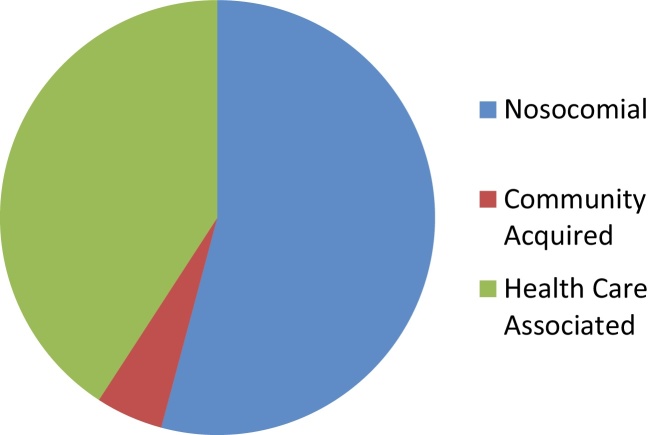

Culture negative specimens were excluded. In culture positive infections, the source of infection (blood, urine, ascites, skin and respiratory tract sputum/endotracheal tube aspirate/pleural fluid) and microorganisms isolated and their antibiotic susceptibility were noted. The collected data was tabulated in Microsoft excel sheet and analyzed using SPSS version 21 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Types of infection acquired from the community and hospital.

Classification of Antibiotics

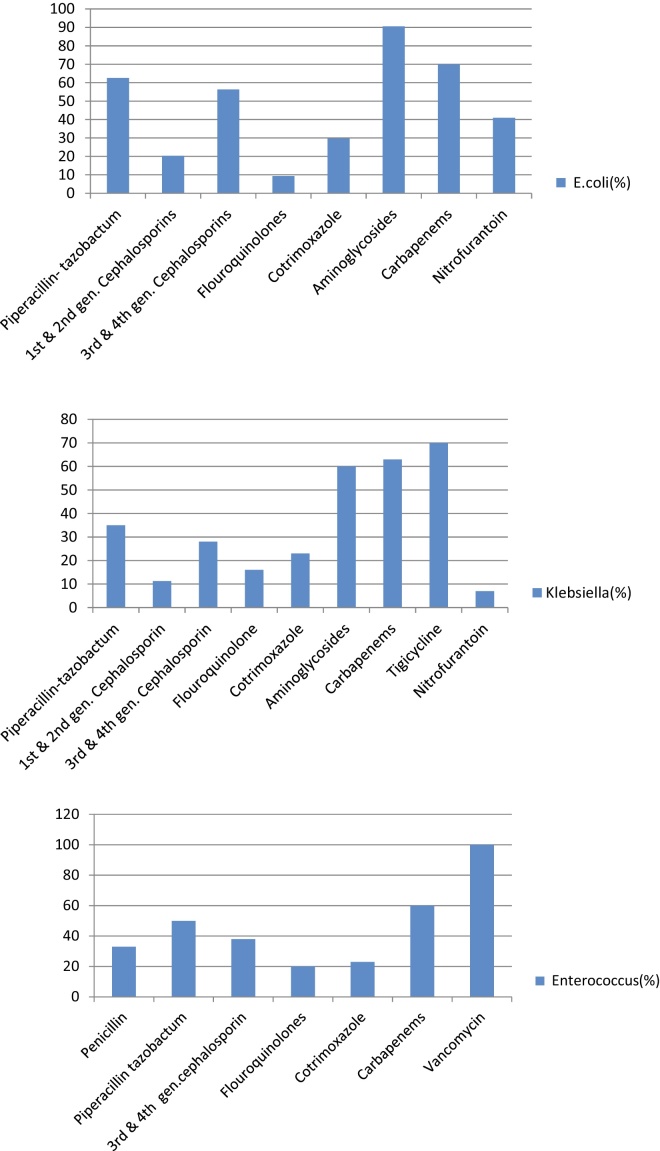

Standard classification was used for classifying the antibiotics11 (Table 1). Tabulation was made for antibiotic sensitivity and resistance for the most common causative pathogens (Figure 4).

Table 1.

Classification of Antibiotics.

| Antibiotic family |

| Penicillin |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid |

| Non-extend spectrum cephalosporins; 1st and 2nd generation |

| Extend-spectrum cephalosporins; 3rd generation |

| Quinolones |

| Cirofloxacin |

| Nalidixic acid |

| Ofloxacin |

| Folate pathway inhibitors |

| Septran |

| Tetracyclines |

| Aminoglycosides |

| Amikacin |

| Gentamicin |

| Phenicols |

| Chloramphenicol |

| Nitrofurans |

| Nitrofurantoin |

| Glycopeptides |

| Vancomycin |

| Carbapenems |

Figure 4.

Antibiotic sensitivity pattern of E. coli, Klebsiella and Enterococcus (%).

Multiresistant (MR) bacteria12 are resistant to 3 or more of the principal antibiotic families, including β-lactams. The most common bacteria are extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), carbapenemase producing Klebsiella (CPK) and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE).

Results

Three hundred and fourteen patients were screened for infection. Culture samples were sent for 151 patients. 92 patients were culture positive during the study period. Fifty-three patients were culture positive at first admission and remaining thereafter.

The median age of the 92 patients was 53 years (range: 22–67) with male preponderance (80 patients). The most common cause for cirrhosis was alcohol related (37 patients; 40.2%) followed by Non alcoholic Steato hepatitis (NASH)/cryptogenic (25 patients; 27.2%) and hepatotropic viruses (22 patients; 23.9%); remaining were rare (autoimmune (AI): 2 patients; combination 6 patients). Forty-one patients had no co-morbidity. Diabetes was existent in 34 (36.9%); hypertension in 20 (21.7%), hypothyroid in 3 (3.3%) and combination in the remaining. Majority of the patients belonged to child turcotte pugh (CTP)-A (43 patients; 46.7%); 21 (22.8%) and 28 patients (30.4%) belonged to CTP B and C respectively. The median model of end stage liver disease (MELD) for CTP A, B and C were 17 (range: 7–39), 17 (range: 8–35) and 28 (range: 15–28) respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline Demographic Characteristics of the Study Group.

| Patient characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Median age | 53 years (range: 22–67) |

| Male:female | 80:12 |

| Etiology | |

| Alcohol | 37 (40.2) |

| Hepatotropic virus | 22 (23.9) |

| NASH/cryptogenic | 25 (27.2) |

| Others & in combination | 8 (8.7) |

| Co-morbidity | |

| Diabetes | 34 (36.9) |

| Hypertension | 20 (21.7) |

| Hypothyroid | 3 (3.3) |

| MELD at registration | |

| CTP A | 43 (46.7) |

| CTP B | 21 (22.8) |

| CTP C | 28 (30.4) |

Ninety-two patients had 240 culture positive samples in the study period between August 2014 and September 2015. The average number of samples per patient was 3 (range: 1–6). The source and distribution of the culture positive samples is mentioned in Table 3. The most common infections with positive cultures were UTI, blood, skin and respiratory infections.

Table 3.

Type and Source of Infection with Resistance Pattern.

| Type of infection | No. of patients | Blood | Ascites | Skin | Urine | Respiratory tract |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nosocomial | 131 | 51 (38.9) | 2 (1.53) | 10 (7.6) | 49 (37.4) | 19 (14.5) |

| HCA | 98 | 30 (30.6) | 5 (5.1) | 15 (15.3) | 42 (42.9) | 6 (6.1) |

| CAI | 11 | 4 (36.4) | – | – | 7 (63.6) | – |

| Total | 240 | 85 (35.4) | 7 (2.9) | 25 (10.4) | 98 (40.8) | 25 (10.4) |

CAI, community acquired infection; HCA, healthcare associated infection.

Gram negative bacterial (GNB) infections (198; 82.5%) were predominant. The major gram negative pathogens in decreasing order of frequency was Klebsiella (80; 40.4%), followed by E. coli (64; 32.3%) and Pseudomonas (17; 8.6%). The rest were rare.

Forty-two samples (17.5%) showed growth of gram positive bacteria. The most common isolate was Enterococcus (39; 92.9%) and S. aureus (2) and Streptococci (1) were extremely rare.

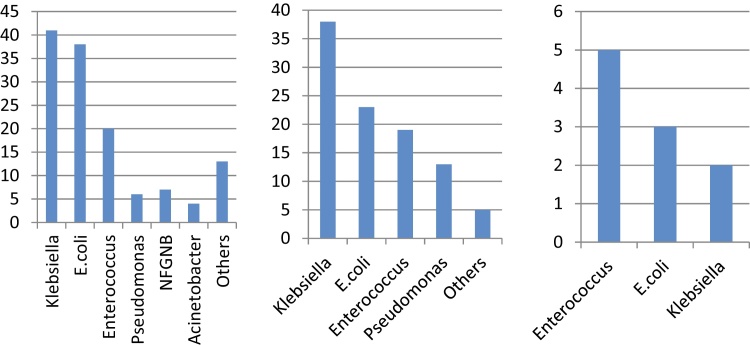

Figure 2 shows the bacteriological profile in nosocomial, HCA and CAI respectively. In HCA and nosocomial infection, the most common isolate was Klebseilla followed by E. coli and Enterococcus. In CAI, the profile was reversed, i.e. Enteroccocus followed by E. coli and Klebsiella.

Figure 2.

Bacterial isolates in nosocomial, health care associated and community acquired infections.

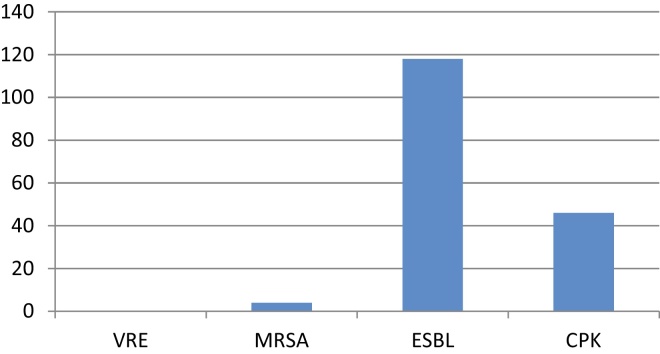

The antibiotic sensitivity pattern was analyzed for the 3 major causative organisms namely E. coli, Klebsiella and enterococcus (Figure 4). The most common resistant strains were ESBL (116, 48.3%) followed by CPK (46, 19.16%) and MRSA (4, 1.6%).

Discussion

Bacterial infections in cirrhotics are not only more frequent but are also responsible for deterioration of a stable condition. Infection is known to increase death rate by four fold reaching almost 38% at one month.13 Prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment of infection is crucial in the management of patients with cirrhosis.14, 15 In our series, GNB were the most frequent bacteria causing nosocomial and HCA infection (82.5%), while GPC were more prevalent in CAI (17.5%). In a recent multicentric study done from Western States of the Indian subcontinent,21 majority of the infections in cirrhotics were HCA or nosocomial infection. The comparison between our data and Baijal et al. study is seen in Table 4. The culture positivity in ascitic fluid was very low in our series. This may be due to use of prophylactic antibiotics or our institutional practice of not sending cultures routinely for patients on large volume paracentesis (Figure 3).

Table 4.

Comparison of Our Study with a Multicentric Study from Western India.

| Parameter | Baijal et al.,21 (106 patients out of 420 had infection) | (Culture positive no. 240) |

|---|---|---|

| Type of infection | ||

| Nosocomial | 30.2% | 54.58% |

| HCA | 50% | 40.83% |

| CAI | 19.8% | 4.5% |

| Site of infection | ||

| Urine | 22.6% | 40.8% |

| Blood | – | 35.4% |

| Respiratory | 11.3% | 10.4% |

| Ascites | 31.1% | 2.9% |

| Cellulitis | 11.3% | 10.4% |

| Type of organism | ||

| Gram negative | 54% | 82.5% |

| Gram positive | 46% | 17.5% |

| MDR | 41.7% | 69.16% |

CAI, community acquired infection; HCA, healthcare associated infection, MDR, multi drug resistant organisms.

Figure 3.

Types of multidrug resistant organisms.

We analyzed antibiotic sensitivity pattern for three major organisms such as E. coli, Klebsiella and Enterococcus. The sensitivity to flouroquinolones was alarmingly low. The sensitivity patterns to third generation cephalosporins (TGC), piperacillin-tazobactumand carbapenems were similar. However, most isolates were sensitive to aminoglycosides. All enterococci were sensitive to vancomycin. These results show that prophylaxis with flouroquinolones may not be adequate for our patients. Moreover, the first line empirical therapy should be piperacillin-tazobactum or carbapenems in our setting. Though sensitivity to aminoglycosides is high, they are seldom used for the fear of nephrotoxicity.

HAI has been recognized as one of the risk factors for the failure of empiric antibiotic therapy. The development of antibiotic resistance in nosocomial infections in large part is due to the recent use of antibiotics. In 2000, only 1.2% of bacteria were resistant to TGC. Unfortunately, many recent studies in cirrhotic patients have shown an increase in the prevalence of multidrug resistant (MR) bacterial infections. Fernández et al.,8 a Spanish study reveals that there was a steady increase from 10% to 23% in the prevalence of MR bacterial infections between 1998 and 2011. The MR bacteria were most frequent (35–39%) in the nosocomial setting, with a very low prevalence of 0–4% with CAI. The prevalence of MR bacteria in the HCA setting was intermediate, between 14% and 20%.

In our series, 4/11 organisms in CAI were MRSA (36.6%). Moreover, 54/98 organisms (55%) in HCA setting and 64/131 (48%) isolates in nosocomial setting were multidrug resistant.

Epidemiology of multidrug resistance pattern varies in different countries and even among hospitals located in the same area. The variations are more likely related to local epidemiological factors. For example, ESBL are predominant in Southern Europe and Asia,8 while MRSA and VRE are prevalent in the United States.16 Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae is a current problem described in Italy.17 The empiric antibiotic treatment for HAI in cirrhosis should therefore be adjusted in accordance with the specific regional pattern of multi drug resistance.

A recent multicenter study from India showed that multidrug resistant infection were in 41.2% of cirrhotic patients 21. While comparing with our study, both the studies showed high rate of multidrug resistance infection in patients with ESLD, particularly HCA infection with gram negative organisms.

Recent studies demonstrate that β-lactams are not effective in cirrhosis with HAI.8 TGC have scarce efficacy in HAI (40%). The response of TGC to SBP, UTI and spontaneous bacteremia was 26%, 29% and 18%, respectively. Similar reports of reduced efficacy with TGC has been reported from Italy, Germany and Turkey for SBP, with failure rates ranging from 18% to 41%.12, 18, 19, 20 In the present study, we noted low sensitivity to TGC and flouroquinolones. The sensitivity to piperacillin-tazobactum and carbapenems was better. In our center piperacillin-tazobactum is the choice as an empirical antibiotic at admission.

Efficacy of empirical antibiotic therapy is also lower in HCA infections compared to CAI (73% vs 83%), especially in pneumonia and UTI.

In conclusion, nosocomial infection is the most common type of infection in ESLD patients, with Klebseilla and E. coli predominating. There is a significant rise in antibiotic resistant organisms. Closely monitored prospective studies in multiple centers across the country can provide the true prevalence of the common source, the type of bacterial infection and its acquisition, i.e. community acquired, HCA or nosocomial and resistance pattern.

Pitfalls of the Study

The study was retrospective. Hence, we could not accurately define the community acquired infection especially those in whom details of treatment beyond 90 days were not available. We also did not study the effect of exposure to systemic antibiotics as a risk factor for antibiotic resistance bacterial infection as details were not available in more than 90% of patients.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Byass P. The global burden of liver disease: a challenge for methods and for public health. BMC Med. 2014;12:159. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0159-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernández J., Gustot T. Management of bacterial infections in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2012;56(suppl 1):S1–S12. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(12)60002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gustot T., Durand F., Lebrec D., Vincent J.L., Moreau R. Severe sepsis in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2009;50:2022–2033. doi: 10.1002/hep.23264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tandon P., Garcia-Tsao G. Bacterial infections, sepsis, and multiorgan failure in cirrhosis. Semin Liver Dis. 2008;28:26–42. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1040319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Acevedo J., Fernández J. New determinants of prognosis in bacterial infections in cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7252–7259. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i23.7252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandez J., Arroyo V. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: a growing problem with significant implications. Clin Liver Dis. 2013;2:102–105. doi: 10.1002/cld.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernández J., Navasa M., Gómez J. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: epidemiological changes with invasive procedures and norfloxacin prophylaxis. Hepatology. 2002;35:140–148. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernández J., Acevedo J., Castro M. Prevalence and risk factors of infections by multiresistant bacteria in cirrhosis: a prospective study. Hepatology. 2012;55:1551–1561. doi: 10.1002/hep.25532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Venditti M., Falcone M., Corrao S. Study Group of the Italian Society of Internal Medicine (outcomes of patients hospitalized with community-acquired, health care-associated, and hospital-acquired pneumonia) Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:19–26. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-1-200901060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merli M., Lucidi C., Giannelli V. Cirrhotic patients are at risk for health care-associated bacterial infections. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(11):979–985. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frank U., Tacconelli E. European Standards; 2012. The Daschner Guide to In Hospital Antibiotic Therapy. ISBN: 978-3-642-18401-7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magiorakos A.P., Srinivasan A., Carey R.B. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(3):268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fede G., D’Amico G., Arvaniti V. Renal failure and cirrhosis: a systematic review of mortality and prognosis. J Hepatol. 2012;56:810–818. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pleguezuelo M., Benitez J.M., Jurado J., Montero J.L., De la Mata M. Diagnosis and management of bacterial infections in decompensated cirrhosis. World J Hepatol. 2013;5:16–25. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v5.i1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruns T., Zimmermann H.W., Stallmach A. Risk factors and outcome of bacterial infections in cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:2542–2554. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i10.2542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tandon P., Delisle A., Topal J.E., Garcia-Tsao G. High prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections among patients with cirrhosis at a US liver center. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1291–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piano S., Romano A., Rosi S., Gatta A., Angeli P. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis due to carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: the last therapeutic challenge. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:1234–1237. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328355d8a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angeloni S., Leboffe C., Parente A. Efficacy of current guidelines for the treatment of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in the clinical practice. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:2757–2762. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Umgelter A., Reindl W., Miedaner M., Schmid R.M., Huber W. Failure of current antibiotic first-line regimens and mortality in hospitalized patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Infection. 2009;37:2–8. doi: 10.1007/s15010-008-8060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yakar T., Güçlü M., Serin E., Alişkan H., Husamettin E. A recent evaluation of empirical cephalosporin treatment and antibiotic resistance of changing bacterial profiles in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1149–1154. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0825-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baijal R., Amarapurkar D., Praveen Kumar H.R. A multicenter prospective study of infections related morbidity and mortality in cirrhosis of liver. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2014;33(4):336–342. doi: 10.1007/s12664-014-0461-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]