Significance

Humans breathe ∼20,000 times per day and hundreds of millions of times over the average life span. The neural mechanisms which control respiratory rate are poorly understood. Although it was previously thought that the signal to breathe was solely an excitatory command, we show that selective stimulation of putative CO2-chemosensitive neurons likely initiates inspiration through inhibition. These results argue that the clock which determines respiratory rate operates in two distinct modes: a first mode which is highly modular and allows for flexibility to adapt to everyday behaviors, and a second mode which is specifically recruited in situations of elevated CO2.

Keywords: respiration, breathing, oscillator, optogenetics

Abstract

Central neural networks operate continuously throughout life to control respiration, yet mechanisms regulating ventilatory frequency are poorly understood. Inspiration is generated by the pre-Bötzinger complex of the ventrolateral medulla, where it is thought that excitation increases inspiratory frequency and inhibition causes apnea. To test this model, we used an in vitro optogenetic approach to stimulate select populations of hindbrain neurons and characterize how they modulate frequency. Unexpectedly, we found that inhibition was required for increases in frequency caused by stimulation of Phox2b-lineage, putative CO2-chemosensitive neurons. As a mechanistic explanation for inhibition-dependent increases in frequency, we found that phasic stimulation of inhibitory neurons can increase inspiratory frequency via postinhibitory rebound. We present evidence that Phox2b-mediated increases in frequency are caused by rebound excitation following an inhibitory synaptic volley relayed by expiration. Thus, although it is widely thought that inhibition between inspiration and expiration simply prevents activity in the antagonistic phase, we instead propose a model whereby inhibitory coupling via postinhibitory rebound excitation actually generates fast modes of inspiration.

Mammals constantly adapt their respiratory rate to meet both homeostatic and behavioral needs (1). Several distinct populations of hindbrain neurons modulate inspiratory frequency (2, 3), which is ultimately controlled by the pre-Bötzinger complex (preBötC), a medullary nucleus required for generation of inspiratory bursts (4–8). The preBötC encompasses a heterogeneous population of neurons (9, 10), of which a kernel of excitatory neurons gives rise to inspiratory bursts (11). A subset of these excitatory neurons is derived from Dbx1+ progenitors (12, 13).

The simplest model posits that inspiratory frequency (f) (see Table S1 for definition of terms) is determined by a balance of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic inputs to the preBötC, where excitation increases inspiratory rate and inhibition induces apnea. This model is supported by data demonstrating that (i) stimulation of the preBötC in vivo increases inspiratory rate (14), (ii) selective stimulation of Dbx1+ neurons in medullary slices or in vivo evokes inspiratory bursting (12, 13), and (iii) stimulation of GlyT2+ inhibitory neurons in the preBötC induces apnea (15). Thus, this “mixed input” model is widely used as a basis for understanding physiological changes in f (16, 17).

We tested assumptions of this model in hindbrain–spinal cord preparations from neonatal mice. These preparations are especially advantageous for studying f because in vitro conditions can be tightly controlled, allowing for direct comparison of f between experiments. Using this approach, we unexpectedly found that inhibition is required for sustaining increases in f caused by optogenetic stimulation of putative CO2-chemosensitive neurons. Inhibition-dependent increases in f appeared to depend on a mechanism of postinhibitory rebound following expiration. Thus, although it is widely thought that excitatory neurons generate inspiratory rhythm and inhibitory neurons only coordinate opposing activity between inspiration and expiration, these data instead lead us to propose a model in which fast inspiratory rhythms are actually generated as a result of reciprocal inhibition.

Results

Excitation Increases Inspiratory Frequency.

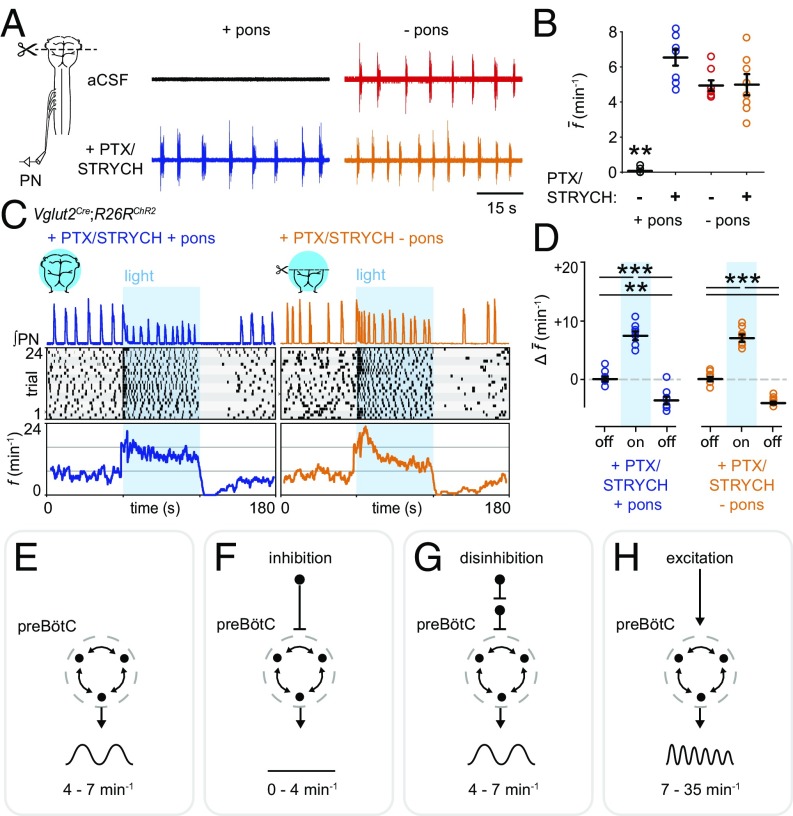

Inspiration can be assayed in neonatal hindbrain–spinal cord preparations by recording from the phrenic nerve (Fig. 1A), which solely innervates the diaphragm. Although preparations retaining the pons do not exhibit spontaneous inspiration, fictive inspiration can be initiated by cutting off the pons at the level of cranial nerve VI (Fig. 1A). Suppression of inspiratory bursting in pontomedullary preparations is thought to be caused by pontine inhibition of the preBötC (18). We found that blocking inhibition by bath application of picrotoxin (PTX)/strychnine hydrochloride (STRYCH) (i.e., disinhibition) completely accounted for increases in f observed upon removal of the pons (Fig. 1 A and B). Importantly, complete inhibitory blockade does not alter the sensitivity of preBötC-generated bursts to opioids (8, 19), indicating that the fundamental mode of inspiratory burst generation is not changed by application of PTX/STRYCH. From these results, we conclude that inhibition suppresses f, and disinhibition (i.e., PTX/STRYCH application) can return f to a baseline frequency of 4–7 min−1 (Fig. 1B; see Table S2 for a summary of results).

Fig. 1.

Excitation increases inspiratory frequency. (A, Top Left) Pontomedullary preparations do not exhibit spontaneous inspiration. (Top Right) Transection at the pontomedullary boundary initiates fictive inspiration. (Bottom Left) PTX/STRYCH application to pontomedullary preparations also initiates fictive inspiration. (Bottom Right) Fictive inspiration initiated via transection at the pontomedullary boundary is not affected by application of PTX/STRYCH. (B) Quantification of average f. **P < 0.01, artificial CSF (aCSF) + pons vs. all other conditions. (C, Top) After application of PTX/STRYCH, stimulation of excitatory neurons resulted in high-frequency inspiratory bursting (fmax + pons = 24.8 min−1; fmax − pons = 35.5 min−1). (Middle) Raster plots were constructed from eight biological replicates (each highlighted by gray shading), with three technical replicates each. (Bottom) f averaged over 24 trials relative to light onset. (D) Change in average f during and after light stimulation relative to baseline (off). PTX/STRYCH + pons: baseline vs. photostimulation, ***P = 1.3 × 10−5. Photostimulation vs. after, ***P = 1.0 × 10−7. Baseline vs. after, **P = 0.0012. PTX/STRYCH − pons: baseline vs. photostimulation, ***P = 3.2 × 10−6. Photostimulation vs. after, ***P = 1.5 × 10−7. Before vs. after, ***P = 2.1 × 10−6. Welch’s ANOVA with Bonferroni correction. n = 8 for each condition. Data are mean ± SEM. (E–H, Top and Middle) Illustration of tested hypothesis and output of preBötC. (Bottom) Summary of finding. (E) Baseline f. (F) Inhibition decreases f (A and B). (G) Disinhibition can return f to baseline frequency but does not increase f above baseline (A and B). (H) Excitation increases f above baseline (C and D).

We next asked whether optogenetic stimulation of large groups of hindbrain glutamatergic neurons would be sufficient to increase f. In Vglut2Cre;R26RChR2 preparations (where Vglut2+ neurons express ChR2-EYFP), photostimulation of Vglut2+ neurons after bath application of PTX/STRYCH led to a dramatic increase in f (Fig. 1 C and D). Even though photostimulation was continuous, phrenic motor neurons exhibited discrete bursting with almost no unit activity during interburst intervals (Fig. 1C), indicating that phrenic motor neuron burst activity in response to photostimulation is generated by an excitatory rhythmogenic substrate rather than downstream premotor nuclei or motor neurons themselves (8). Importantly, the effective population of Vglut2+ neurons stimulated was large, encompassing disparate populations of ventrally positioned excitatory neurons likely interacting with glutamatergic preBötC neurons via monosynaptic or oligosynaptic connections (Fig. S1A; Fig. S1 also contains anatomical characterization of each Cre allele used herein). Thus, after application of PTX/STRYCH, continuous photostimulation of excitatory preBötC neurons and/or upstream excitatory populations causes rhythmic inspiratory bursting at high frequencies.

What mechanisms suppress burst initiation during interburst intervals? Photostimulation was maintained continuously, yet preBötC circuits were resistant to initiating a subsequent burst; Vglut2Cre;R26RChR2 preparations treated with PTX/STRYCH exhibited a minimum interburst interval (IBImin) of 2.42 ± 0.33 s (+pons) and 1.69 ± 0.24 s (−pons, Fig. 1C). Recently, Kottick and Del Negro (12) identified a postburst refractory period during which stimulation of Dbx1+ preBötC neurons could not initiate a subsequent inspiratory burst. Presumably, this refractory period is defined by time constants of activity-dependent outward currents (e.g., Ipump, INa-K, IK-ATP) and/or biophysical constraints associated with synaptic dynamics (12, 20, 21). Importantly, this refractory period imposes a boundary condition that defines maximum inspiratory frequency; fmax is the inverse of IBImin. We found that fmax under conditions of excitation/disinhibition was 24.8 min−1 in pontomedullary preparations and 35.5 min−1 in medullary preparations, values that are comparable to that of preBötC slices (9). Together, these data are consistent with a model in which inhibition decreases f (Fig. 1F), disinhibition (i.e., PTX/STRYCH application) relieves inhibition and returns f to baseline frequency (Fig. 1G), and excitation increases f (Fig. 1H).

Inhibition Is Implicated in Phox2b and Atoh1 Modulation of Frequency.

To validate this model (Fig. 1 E–H), we sought to stimulate select subsets of excitatory hindbrain neurons and characterize how they modulate f. Our results from Fig. 1 indicate that PTX/STRYCH application can discriminate between different modes of f modulation: inhibition is a decrease in f that is PTX/STRYCH sensitive, disinhibition is masked by application of PTX/STRYCH (i.e., blockade of inhibition is disinhibitory), and excitation is an increase in f that is PTX/STRYCH insensitive (Table S2).

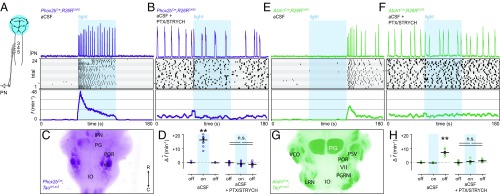

We first stimulated excitatory Phox2b-lineage neurons (Fig. 2A), a contingent of which increase f as part of the central chemoreceptive response to elevated CO2 (22–24). The mechanism underlying Phox2b-mediated increases in f is not well understood, but is thought to result from excitation/disinhibition of the preBötC (16). Photostimulation of excitatory Phox2b-lineage neurons resulted in a dramatic increase in f (Fig. 2 A and D). Surprisingly, we found that PTX/STRYCH application completely abolished Phox2b-mediated increases in f (Fig. 2 B and D). It is likely that broad Phox2b-lineage photostimulation preferably engaged Phox2b+ CO2-chemosensitive neurons because the inspiratory response to hypercapnia (increased CO2) was also abolished by application of PTX/STRYCH (Fig. S2). Importantly, PTX/STRYCH application did not cause the network to enter a state in which it could no longer be excited because broad stimulation of Vglut2+ neurons under these conditions still caused a robust inspiratory response (Fig. 1C). These results indicate that excitation does not explain Phox2b-mediated increases in f.

Fig. 2.

Inhibition is implicated in Phox2b and Atoh1 modulation of inspiratory frequency. (A) Stimulation of Phox2b-lineage neurons dramatically increased f (fmax = 68.6 min−1). (B) Phox2b-mediated increases in f were blocked by bath application of PTX/STRYCH. (C) Anatomical identification of ventral Phox2b-lineage neurons likely stimulated in the brainstem. Arrow indicates rostral and caudal directions. (D) Change in average f during and after light stimulation relative to baseline. Baseline vs. photostimulation, **P = 0.002. Photostimulation vs. after, **P = 0.002. Mann–Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction. PTX/STRYCH blocked the effect of photostimulation (Mann–Whitney U test). (E) Stimulation of Atoh1-lineage neurons resulted in a transient increase in f after the termination of the photostimulus. (F) Atoh1-mediated increases in f were blocked by application of PTX/STRYCH. (G) Position of ventral Atoh1-lineage neurons likely stimulated in the brainstem. (H) Change in average f during and after light stimulation relative to baseline. Baseline vs. after, **P = 0.002. Photostimulation vs. after, **P = 0.002. Mann–Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction. PTX/STRYCH blocked the effect of photostimulation (one-way ANOVA). n = 8 for each condition; data are mean ± SEM.

The inspiratory response to stimulation of Phox2b-lineage neurons (Fig. 2A) exhibited several unique properties compared with excitation caused by photostimulation of Vglut2+ neurons (Fig. 1C). First, stimulation of Phox2b-lineage neurons evoked a remarkable fmax of 68.6 min−1. This fmax was much faster than that observed during broad excitation of Vglut2+ neurons in the absence of inhibition (Fig. S3A), suggesting that inhibition is critical for very fast modes of inspiration. Second, whereas excitation resulted in amplitude depression upon subsequent bursts (Fig. 1C and Fig. S3B), Phox2bCre;R26RChR2-mediated increases in f did not (Fig. 2A and Fig. S3B), suggesting that inhibitory neurons are also involved in sustaining burst amplitude at high frequencies. Finally, whereas excitation evoked inspiratory bursting within 50–150 ms of the photostimulus (Fig. S3C), stimulation of Phox2b-lineage neurons initiated inspiration at a considerable delay (367 ± 30 ms; Fig. S3C). Consistent with previous data (25), we found that Phox2bCre;R26RChR2 increases in f were independent of catecholamines (Fig. S3D). Phox2b-mediated increases in f also required an intact pons (Fig. S3E), suggesting that known ascending Phox2b-lineage axonal projections to the pontine Kölliker-Fuse nucleus may be important (16). Although the mechanism underlying Phox2b-mediated increases in f is not yet clear, these data indicate that inhibitory neurons are actively involved.

To further investigate our working model of f control (Fig. 1 E–H), we examined whether stimulation of excitatory Atoh1-lineage neurons would modulate f. Atoh1-lineage neurons are required for proper respiratory function; Atoh1−/− mice die at birth due to respiratory failure (2, 26–29). We stimulated hindbrain Atoh1-lineage neurons in the absence of spontaneous motor output (+pons). Interestingly, this stimulation paradigm resulted in a transient increase in f only upon termination of the photostimulus (Fig. 2E; half-life of t1/2 ∼ 18 s). Because this Atoh1 response was out of phase with the photostimulus (Fig. 2E), we reasoned that inhibitory neurons were again likely to be involved. Consistent with this hypothesis, Atoh1-mediated increases in f were blocked by bath application of PTX/STRYCH (Fig. 2F). We sought to determine whether stimulation of Atoh1-lineage neurons would suppress fictive inspiration; however, we found that Atoh1-mediated changes in f also required an intact pons (Fig. S4A). Therefore, we examined whether stimulation of Atoh1-lineage neurons would suppress substance P-initiated inspiratory bursting in preparations retaining the pons (Fig. S4B). Substance P facilitates inspiratory bursting by neurokinin-1 receptor-dependent activation of Nalcn, a sodium leak channel (30). Indeed, we found that photostimulation of Atoh1-lineage neurons suppressed substance P-initiated inspiration (Fig. S4B), demonstrating that excitatory Atoh1-lineage neurons engage the preBötC through inhibition (Fig. 1F). Importantly, these results indicate that inhibitory neurons contribute to circuit dynamics that can promote initiation of inspiratory bursts.

Phasic Inhibition Increases Inspiratory Frequency.

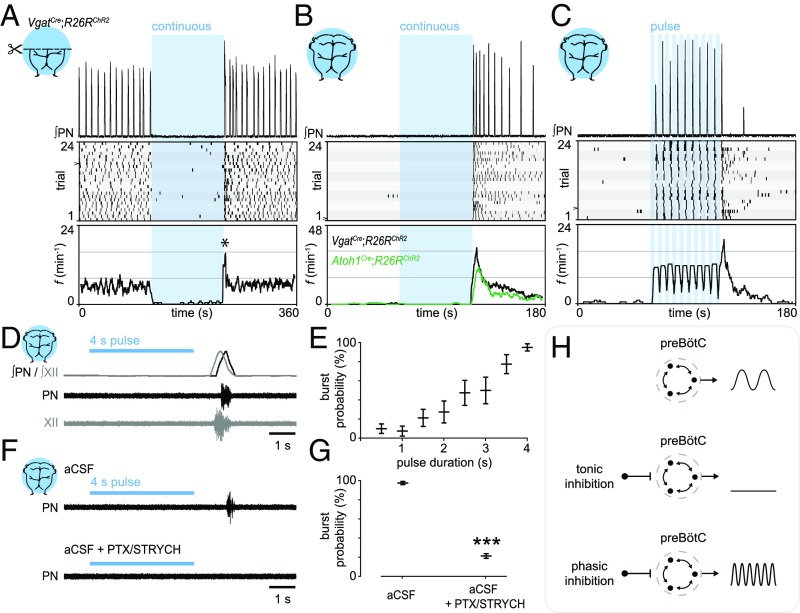

We directly investigated inhibitory mechanisms which contribute to increases in f. In VgatCre;R26RChR2 medullary preparations (−pons), we found that continuous photostimulation of GABA/glycinergic neurons immediately induced apnea (Fig. 3A). Indeed, prolonged photostimulation of medullary Vgat+ neurons almost completely arrested inspiration for the duration of the stimulus (120 s; Fig. 3A). We observed a transient increase in f upon termination of the photostimulus (Fig. 3A; half-life of t1/2 ∼ 4 s). This increase in f is reminiscent of the “reset” phenomenon observed in response to stimulation of preBötC GlyT2+ neurons in awake mice, where the first inspiratory burst occurs at a consistent latency after photostimulation (15).

Fig. 3.

Phasic inhibition can drive increases in inspiratory frequency. (A) Photostimulation of Vgat+ neurons during fictive inspiration suppressed burst initiation for the duration of the photostimulus. (Bottom) Analysis of f indicated a reset-like response upon light off (asterisk, half-life of t1/2 ∼ 4 s). (B) In a silent preparation, stimulation of Vgat+ neurons evoked inspiratory bursting via a rebound-like mechanism (half-life of t1/2 ∼ 23 s). (C) Phasic inhibition evoked inspiratory bursting at high frequencies. (D) Rebound bursts recruit both phrenic and hypoglossal motor neurons (n = 5), indicating that rebound bursts arise from the preBötC. (E) The probability of observing a rebound burst in response to stimulation of inhibitory neurons was directly proportional to the photostimulus duration. n = 8; data are mean ± SEM. (F and G) PTX/STRYCH application blocked rebound inspiratory bursts caused by stimulation of inhibitory neurons. The pulse of light in the Bottom was performed between two spontaneous bursts (outside trace). ***P = 5.5 × 10−4. Mann–Whitney U test. n = 8; data are mean ± SEM. (H) Whereas tonic inhibition suppresses inspiratory burst initiation, phasic inhibition can actually increase f via postinhibitory rebound.

To examine the nature of this mechanism, we reasoned that stimulation of inhibitory neurons in a silent preparation (+pons) would differentiate between reset and rebound. This is an important distinction to make because reset implies that inhibitory neurons simply dictate when the preBötC cannot initiate a burst, whereas rebound indicates that inhibition actually drives preBötC bursting. In pontomedullary preparations, we found that a 60-s stimulus resulted in a pronounced rebound response (Fig. 3B; half-life of t1/2 ∼ 23 s). Furthermore, phasic inhibition induced sustained increases in f (Fig. 3C), indicating that inhibition does not simply pattern the activity of an ongoing rhythm, but can drive inspiration at a high frequency. Rebound inspiratory bursts were observed from both phrenic and hypoglossal motor neurons (Fig. 3D), which are controlled by different premotor nuclei. These data indicate that rebound bursts arise at the level of the preBötC rather than from downstream premotor nuclei or from motor neurons themselves. The probability of observing a rebound inspiratory burst was directly proportional to the photostimulus duration (Fig. 3E), indicating that the characteristics of an inhibitory synaptic volley predict the postsynaptic inspiratory response. Finally, rebound inspiratory bursts were blocked by application of PTX/STRYCH (Fig. 3 F and G). We conclude that, in addition to excitation (Fig. 1H), phasic inhibition is a mechanism that can increase f (Fig. 3H).

Phox2b-Lineage Neurons Initiate Expiration.

Our results indicate that neither excitation nor disinhibition can account for Phox2b-mediated increases in f (Fig. 2 B and D); therefore, we examined whether Phox2b-lineage neurons might increase f through phasic inhibition. Although Phox2b+, CO2-chemosensitive neurons do not exhibit phasic activity themselves (3), they are situated within the parafacial (pF) nucleus close to a group of excitatory neurons which exhibits phasic oscillatory activity associated with expiration (known as the pF oscillator) (31–34). Although mechanisms of inspiratory/expiratory coupling are not well understood (31), it is widely thought that inhibition is responsible for antiphasic inspiratory/expiratory patterning because purely excitatory networks exhibit synchrony (8, 35, 36). Thus, in the context of Phox2b-lineage photostimulation, expiration might actually initiate inspiration through phasic inhibition.

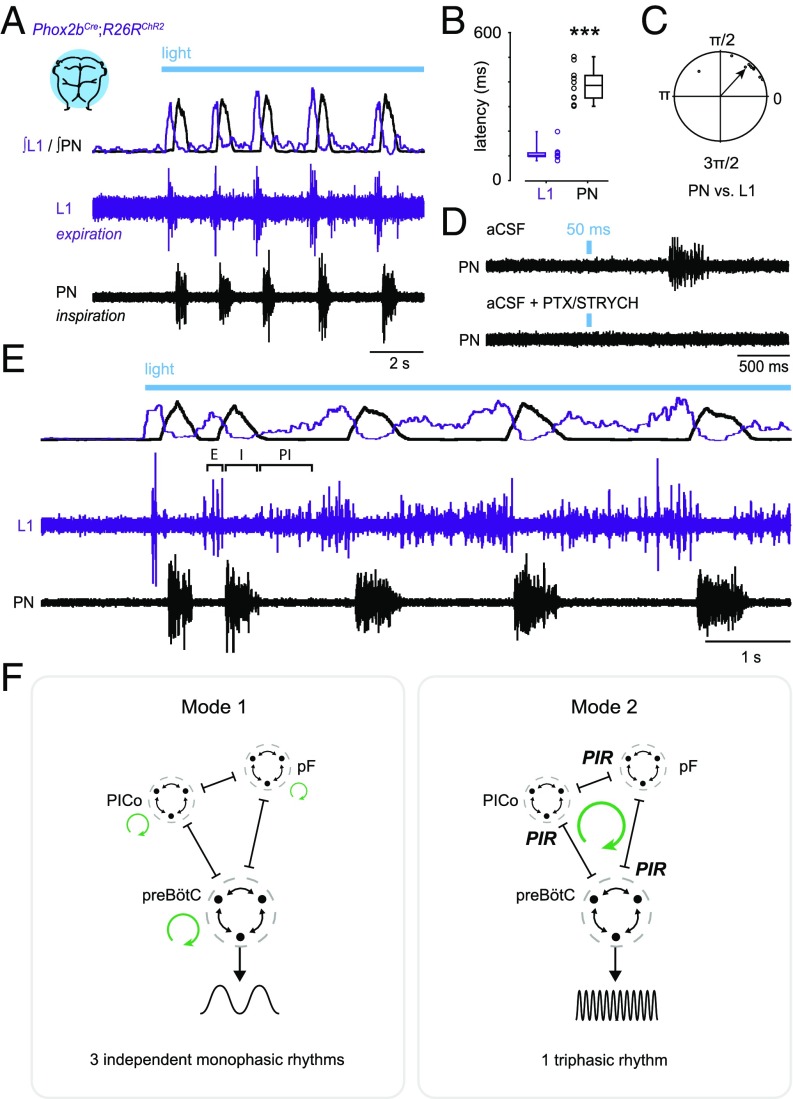

Whereas neonatal preparations normally exhibit passive rather than active expiration (37), which we confirmed (Fig. S5A), we found—strikingly—that stimulation of Phox2b-lineage neurons evoked active expiratory activity alternating with inspiratory activity (Fig. 4A). Expiration was assayed by recording from motor neurons of the L1 ventral root, a contingent of which innervate abdominal muscles that are engaged during active expiration (27, 38). Photostimulation of Phox2b-lineage neurons immediately evoked expiratory bursting from the L1 ventral root (Fig. 4 A and B; L1 latency, 113 ± 11 ms), which was only then followed by an inspiratory response (Fig. 4 A and B; PN latency, 389 ± 20 ms). The latency of expiration was consistent with a direct excitatory response (Fig. 4B; compare with PN excitation, Fig. S3C). Photostimulation of Phox2b-lineage neurons for 50 ms was sufficient to cause an inspiratory burst several hundreds of milliseconds later (Fig. 4D), a response which was blocked by application of PTX/STRYCH (Fig. 4D; see also Fig. 2B).

Fig. 4.

Phox2b-lineage neurons evoke expiration, inspiration, and postinspiration. (A) Stimulation of Phox2b-lineage neurons evoked phasic expiratory (L1, abdominal) motor activity preceding inspiratory bursts. (Top) Integrated and rectified traces. (Bottom) Raw traces. (B) Latency to first response. n = 10 preparations; ***P = 0.0002, Mann–Whitney U test. (C) Coupling between PN and L1 exhibited a phase separation of 0.85 ± 0.17 rad (49 ± 10°; n = 10). (D) The 50-ms Phox2bCre;R26RChR2 photostimulation was sufficient to cause an inspiratory burst several hundreds of milliseconds later. This inspiratory response was blocked by application of PTX/STRYCH (Fig. 2B). The pulse of light in the Bottom was performed between two spontaneous bursts (outside trace). (E) Stimulation of Phox2b-lineage neurons evoked all three phases of respiration—expiration (E), inspiration (I), and postinspiration (PI), forming a continuous triphasic rhythm. (F) Illustration of proposed coupling between E, I, and PI. In mode 1, inhibition does not couple E/I/PI and instead causes antiphasic patterning (38). Here, rhythmic oscillations (represented by green circular arrows) in motor output are the consequence of excitatory mechanisms. In mode 2, inhibition causes postinhibitory rebound, which acts to couple E, I, and PI. Here, rhythmic oscillation (represented by a single green circular arrow) is generated as a consequence of inhibitory synaptic coupling between E, I, and PI. pF, parafacial oscillator (E); preBötC (I); PICo, postinspiratory complex (PI); PIR, postinhibitory rebound excitation.

In n = 4 of 10 preparations in which we obtained a stronger signal from the L1 ventral root (compare Fig. 4A with Fig. 4E), we observed full triphasic rhythms consisting of expiratory, inspiratory, and postinspiratory bursting (Fig. 4E). These data indicate that Phox2b-mediated increases in f do not represent sniffing behavior, which consists solely of inspiratory/postinspiratory bursting (an elimination of the expiratory phase) (39, 40). Moreover, because pontomedullary preparations do not exhibit any spontaneous activity from the PN or L1 ventral root (see Fig. 4 A and E before photostimulus), these data indicate that stimulation of Phox2b-lineage neurons evokes all three phases of respiration—expiration, inspiration, and postinspiration (Fig. 4E), suggesting a mode of unitary oscillation in which one phase drives increases in the frequency of a subsequent phase (Fig. 4F, mode 2).

We used high-speed video to further examine how the inspiratory rhythms we observed control the muscular apparatus. During fictive inspiration (−pons), we observed upward (inspiratory) ribcage movements (Fig. S5A and Movie S1). We found that after initial upward deflection, the ribcage returned downward to its original position long after the termination of phrenic inspiratory bursts (Fig. S5A), suggesting that expiration in these conditions is passive. In stark contrast, photostimulation of Phox2b-lineage neurons initially caused downward (expiratory) ribcage movements which were quickly followed by upward deflection of the ribcage (Fig. S5B). The ribcage then returned to its original position upon termination of phrenic inspiratory bursts (Fig. S5B and Movie S1).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that inhibition is critical for certain physiological modes of increased inspiratory frequency. The mechanism of inhibition-dependent increases in f is independent of previously proposed models which depend on disinhibition (17). We found that disinhibition is not a mechanism which increases f above baseline frequency. Instead, the mechanism of inhibition-dependent increases in f appears to involve postinhibitory rebound excitation. Photostimulation of Phox2b-lineage, putative CO2-chemosensitive neurons evoked alternating expiratory/inspiratory activity, and resultant increases in inspiratory frequency were completely abolished by application of PTX/STRYCH. These data lead us to propose a model in which rhythmic inspiratory bursting can be generated by the medulla in two functionally distinct modes: excitatory circuits alone are sufficient for generation of rhythm—but a second mode of rhythm generation involving reciprocal inhibition between inspiration/expiration/postinspiration acts in parallel to achieve homeostatic and behavioral needs.

An Inhibitory Mechanism of Rhythm Generation.

How do inhibitory neurons contribute to generation of inspiratory rhythms? In the simplest model, two inhibitory neurons with reciprocal connectivity exhibit antiphasic patterning, that is, one neuron fires while the other is inhibited. Adding rebound kinetics to this system causes the output of each neuron to become rhythmic (41). In this reduced form, rhythm generation (rhythmic output of each neuron) and pattern formation (antiphasic output of each neuron) are one and the same. We propose that this type of rhythm generation is responsible for Phox2bCre;R26RChR2-mediated increases in f. Thus, under certain circumstances, respiratory rhythm generation and pattern formation may be network features that are inherently yoked. A similar type of rhythm generation has been extensively characterized in left/right swimming in the Xenopus tadpole (42, 43).

Modularity in Respiratory Control.

During eupnea (resting unlabored breathing), inspiratory and expiratory burst frequency can be manipulated independently with µ-opioid receptor-directed perturbations (38). These data suggest that the respiratory system is modular, such that one phase does not drive a subsequent phase (e.g., expiration does not cause inspiration). Modular design could allow for considerable behavioral flexibility in vocalization, swallowing, sigh, etc. In this case, reciprocal inhibitory coupling would simply prevent activity in the antagonistic phase (Fig. 4F, mode 1).

It was recently proposed, however, that in some situations expiration might actually excite inspiration, and vice versa (31). Our data suggest that there is indeed a “switch,” such that under certain circumstances expiration actually initiates inspiration through phasic inhibition. This type of inhibitory coupling between inspiration/expiration is fundamentally different from antagonistic motor patterning observed during eupnea (38). Presumably, if an inhibitory synaptic volley relayed by expiration initiates inspiration, then the shape of the (present) inspiratory burst will be defined, in part, by characteristics of that (previous) inhibitory synaptic volley. This type of rhythm is deterministic, implying that rapid respiratory rates exhibit stereotyped motor patterns (Fig. 4F, mode 2). The concept of deterministic rhythms might help to explain long-lasting effects on f after a given stimulus. For example, we found that increases in f following a long inhibitory photostimulus persisted for several seconds (half-life of t1/2 ∼ 23 s). In another example, photostimulation of Phox2b+ neurons in adult rats caused long-lasting (t1/2 ∼ 11 s) effects on f in vivo (24).

Although it is unclear what underlies a switch between modes, the strength of inhibitory synaptic coupling is likely to contribute. In Xenopus tadpoles, a right/left swimming rhythm is thought to depend on postinhibitory rebound during reciprocal inhibition between sides (42). Here, the strength of inhibition (defined by the amplitude of inhibitory postsynaptic potentials in descending interneurons) dictated the probability of observing a rebound burst (42). We also found evidence that the “strength” of an inhibitory stimulus (defined by photostimulus duration) dictates the probability of observing a rebound inspiratory burst. Importantly, rebound bursts are, by definition, increases in f in comparison with inhibitory synaptic volleys that do not evoke rebound. This suggests that inspiratory rhythms driven by postinhibitory rebound (mode 2) operate at a higher frequency. Indeed, in Xenopus tadpoles, weakening phasic inhibition without changing background excitation slows down left/right swimming rhythms (43). Thus, it is possible that there are frequency-dependent modes of inspiratory rhythm generation (i.e., mode 1, low frequency; mode 2, high frequency); however, the range of frequencies over which each mode operates is entirely unclear—these ranges may exhibit extensive overlap. Interestingly, we found evidence that mode 1 and mode 2 do segregate at least at very high frequencies: Phox2b-lineage photostimulation evoked inspiratory frequencies which far exceeded those which could be evoked by stimulation of Vglut2+ neurons after inhibitory blockade.

Mechanism of Rebound Excitation.

What mechanism governs postinhibitory rebound excitation? One possibility is that rebound excitation is mediated by hyperpolarization-activated cation current (Ih) carried by HCN channels (44). In preBötC slices, application of Cs2+ or ZD7288 blocks only a portion of Ih observed in inspiratory preBötC neurons (44), suggesting that HCN-independent mechanisms also contribute. Inward current from T- and L-type calcium channels is known to activate upon hyperpolarization in certain contexts (45, 46). Rebound bursts might also be independent of hyperpolarization-activated inward currents altogether: in one example, Purkinje cells of the cerebellar cortex can synchronize fast-spiking target neurons in the deep cerebellar nuclei via inhibition (47). It is possible that an inhibitory synaptic volley relayed by expiration could synchronize subthreshold activity within the preBötC in a similar manner. Although neurons of the preBötC do not exhibit a high intrinsic firing rate, synchronization of just a few neurons is thought to be sufficient to evoke a population-wide burst (48).

Understanding rebound mechanisms will likely be difficult without better identification of the underlying anatomical substrate(s) involved. Importantly, our results do not shed light on the anatomical location of the inhibitory neurons which mediate responses generated by stimulation of Phox2b-lineage, Atoh1-lineage, and Vgat+ neurons—which may ultimately exert their effects on the preBötC through any number of different relay configurations (Table S2). Indeed, using the VgatCre allele, we could not recapitulate high frequencies evoked by stimulation of Phox2b-lineage neurons alone, which is likely due to broad engagement of inhibitory neurons using this VgatCre approach. In support of this interpretation, we found that rebound bursts were evoked at a variable latency following termination of the photostimulus (100–2,000 ms).

Materials and Methods

For a full description of all materials and methods, see SI Materials and Methods.

Animals.

All animal procedures were approved by the Case Western Reserve University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Vglut2Cre (49), Phox2bCre (50), Atoh1Cre (51), or VgatCre (49) mice were crossed to R26RChR2-EYFP, R26RLacZ, or Taulsl-LacZ reporter mice. Experiments were performed with male/female postnatal day 2 (P2) to P4 mice using heterozygous combinations of alleles.

Recording and Drugs.

After cryoanesthesia, the caudal neural axis was exposed under oxygenated Ringer’s solution and the phrenic nerves were dissected free. Suction electrodes were attached to the phrenic nerve, hypoglossal nerve, or the L1 ventral root, and signal was amplified. Photostimulation was carried out with a Polychrome V monochromator at a light intensity of 0.2 mW⋅mm−2. We used the following drugs: PTX (10 µM), STRYCH (0.3 µM), prazosin (25 µM), propranolol (25 µM), and substance P (1 µM).

Analysis and Statistics.

Representative raw or integrated (rectified, smoothed) traces are presented. Burst time and duration are quantified with respect to light onset. In raster plots, individual bursts are represented by black rectangles. Instantaneous frequency (f) is calculated continuously every 0.1 s over 24 trials (bin = 5 s). Phase relationships between PN and L1 were determined using circular plot analysis (52). Details on statistical analyses are available in the legends. Data are mean ± SEM.

X-Gal Staining and Imaging.

We performed whole-mount X-gal staining for 2 h at 37 °C, which allowed X-gal substrate to react with LacZ-expressing cells positioned within 152 ± 13 µm (n = 3) of the tissue surface. Whole-mount bright-field images were captured using a stereomicroscope.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank JingQiang You for technical assistance. This work was supported by National Science Foundation Grant DGE-0951783 (to J.M.C.), NIH Grant U01EB21960 (to T.E.D.), NIH Grant NS074199 (to L.T.L.), and NIH Grant NS025713 (to J.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1711536114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Dutschmann M, Dick TE. Pontine mechanisms of respiratory control. Compr Physiol. 2012;2:2443–2469. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c100015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rose MF, et al. Math1 is essential for the development of hindbrain neurons critical for perinatal breathing. Neuron. 2009;64:341–354. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mulkey DK, et al. Respiratory control by ventral surface chemoreceptor neurons in rats. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:1360–1369. doi: 10.1038/nn1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones SE, Dutschmann M. Testing the hypothesis of neurodegeneracy in respiratory network function with a priori transected arterially perfused brain stem preparation of rat. J Neurophysiol. 2016;115:2593–2607. doi: 10.1152/jn.01073.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith JC, Ellenberger HH, Ballanyi K, Richter DW, Feldman JL. Pre-Bötzinger complex: A brainstem region that may generate respiratory rhythm in mammals. Science. 1991;254:726–729. doi: 10.1126/science.1683005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramirez JM, Schwarzacher SW, Pierrefiche O, Olivera BM, Richter DW. Selective lesioning of the cat pre-Bötzinger complex in vivo eliminates breathing but not gasping. J Physiol. 1998;507:895–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.895bs.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan W, et al. Silencing preBötzinger complex somatostatin-expressing neurons induces persistent apnea in awake rat. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:538–540. doi: 10.1038/nn.2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cregg JM, et al. A latent propriospinal network can restore diaphragm function after high cervical spinal cord injury. Cell Rep. 2017;21:654–665. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.09.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgado-Valle C, Baca SM, Feldman JL. Glycinergic pacemaker neurons in preBötzinger complex of neonatal mouse. J Neurosci. 2010;30:3634–3639. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3040-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdala AP, Paton JFR, Smith JC. Defining inhibitory neurone function in respiratory circuits: Opportunities with optogenetics? J Physiol. 2015;593:3033–3046. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.280610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janczewski WA, Tashima A, Hsu P, Cui Y, Feldman JL. Role of inhibition in respiratory pattern generation. J Neurosci. 2013;33:5454–5465. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1595-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kottick A, Del Negro CA. Synaptic depression influences inspiratory-expiratory phase transition in Dbx1 interneurons of the preBötzinger complex in neonatal mice. J Neurosci. 2015;35:11606–11611. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0351-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cui Y, et al. Defining preBötzinger complex rhythm- and pattern-generating neural microcircuits in vivo. Neuron. 2016;91:602–614. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alsahafi Z, Dickson CT, Pagliardini S. Optogenetic excitation of preBötzinger complex neurons potently drives inspiratory activity in vivo. J Physiol. 2015;593:3673–3692. doi: 10.1113/JP270471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherman D, Worrell JW, Cui Y, Feldman JL. Optogenetic perturbation of preBötzinger complex inhibitory neurons modulates respiratory pattern. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:408–414. doi: 10.1038/nn.3938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guyenet PG, Bayliss DA. Neural control of breathing and CO2 homeostasis. Neuron. 2015;87:946–961. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marchenko V, et al. Perturbations of respiratory rhythm and pattern by disrupting synaptic inhibition within pre-Bötzinger and Bötzinger complexes. eNeuro. 2016;3:ENEURO.0011-16.2016. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0011-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hilaire G, Bou C, Monteau R. Rostral ventrolateral medulla and respiratory rhythmogenesis in mice. Neurosci Lett. 1997;224:13–16. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)13458-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gray PA, Rekling JC, Bocchiaro CM, Feldman JL. Modulation of respiratory frequency by peptidergic input to rhythmogenic neurons in the preBötzinger complex. Science. 1999;286:1566–1568. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5444.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubin JE, Hayes JA, Mendenhall JL, Del Negro CA. Calcium-activated nonspecific cation current and synaptic depression promote network-dependent burst oscillations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:2939–2944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808776106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guerrier C, Hayes JA, Fortin G, Holcman D. Robust network oscillations during mammalian respiratory rhythm generation driven by synaptic dynamics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:9728–9733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421997112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amiel J, et al. Polyalanine expansion and frameshift mutations of the paired-like homeobox gene PHOX2B in congenital central hypoventilation syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;33:459–461. doi: 10.1038/ng1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dubreuil V, et al. A human mutation in Phox2b causes lack of CO2 chemosensitivity, fatal central apnea, and specific loss of parafacial neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:1067–1072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709115105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abbott SBG, et al. Photostimulation of retrotrapezoid nucleus phox2b-expressing neurons in vivo produces long-lasting activation of breathing in rats. J Neurosci. 2009;29:5806–5819. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1106-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holloway BB, Viar KE, Stornetta RL, Guyenet PG. The retrotrapezoid nucleus stimulates breathing by releasing glutamate in adult conscious mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2015;42:2271–2282. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang WH, et al. Atoh1 governs the migration of postmitotic neurons that shape respiratory effectiveness at birth and chemoresponsiveness in adulthood. Neuron. 2012;75:799–809. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tupal S, et al. Atoh1-dependent rhombic lip neurons are required for temporal delay between independent respiratory oscillators in embryonic mice. Elife. 2014;3:e02265. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruffault PL, et al. The retrotrapezoid nucleus neurons expressing Atoh1 and Phox2b are essential for the respiratory response to CO2. Elife. 2015;4:e07051. doi: 10.7554/eLife.07051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maricich SM, et al. Merkel cells are essential for light-touch responses. Science. 2009;324:1580–1582. doi: 10.1126/science.1172890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yeh SY, et al. Respiratory network stability and modulatory response to substance P require Nalcn. Neuron. 2017;94:294–303.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huckstepp RT, Henderson LE, Cardoza KP, Feldman JL. Interactions between respiratory oscillators in adult rats. Elife. 2016;5:e14203. doi: 10.7554/eLife.14203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huckstepp RTR, Cardoza KP, Henderson LE, Feldman JL. Role of parafacial nuclei in control of breathing in adult rats. J Neurosci. 2015;35:1052–1067. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2953-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thoby-Brisson M, et al. Genetic identification of an embryonic parafacial oscillator coupling to the preBötzinger complex. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1028–1035. doi: 10.1038/nn.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pagliardini S, et al. Active expiration induced by excitation of ventral medulla in adult anesthetized rats. J Neurosci. 2011;31:2895–2905. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5338-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Talpalar AE, et al. Identification of minimal neuronal networks involved in flexor-extensor alternation in the mammalian spinal cord. Neuron. 2011;71:1071–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson TM, et al. A novel excitatory network for the control of breathing. Nature. 2016;536:76–80. doi: 10.1038/nature18944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith JC, Greer JJ, Liu GS, Feldman JL. Neural mechanisms generating respiratory pattern in mammalian brain stem-spinal cord in vitro. I. Spatiotemporal patterns of motor and medullary neuron activity. J Neurophysiol. 1990;64:1149–1169. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.64.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Janczewski WA, Feldman JL. Distinct rhythm generators for inspiration and expiration in the juvenile rat. J Physiol. 2006;570:407–420. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.098848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lawson EE, Richter DW, Czyzyk-Krzeska MF, Bischoff A, Rudesill RC. Respiratory neuronal activity during apnea and other breathing patterns induced by laryngeal stimulation. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1991;70:2742–2749. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.70.6.2742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pérez de Los Cobos Pallares F, Bautista TG, Stanić D, Egger V, Dutschmann M. Brainstem-mediated sniffing and respiratory modulation during odor stimulation. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2016;233:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perkel DH, Mulloney B. Motor pattern production in reciprocally inhibitory neurons exhibiting postinhibitory rebound. Science. 1974;185:181–183. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4146.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moult PR, Cottrell GA, Li WC. Fast silencing reveals a lost role for reciprocal inhibition in locomotion. Neuron. 2013;77:129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li WC, Moult PR. The control of locomotor frequency by excitation and inhibition. J Neurosci. 2012;32:6220–6230. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6289-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thoby-Brisson M, Telgkamp P, Ramirez JM. The role of the hyperpolarization-activated current in modulating rhythmic activity in the isolated respiratory network of mice. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2994–3005. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02994.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Engbers JDT, et al. Distinct roles for IT and IH in controlling the frequency and timing of rebound spike responses. J Physiol. 2011;589:5391–5413. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.215632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang D, Grillner S, Wallén P. 5-HT and dopamine modulates CaV1.3 calcium channels involved in postinhibitory rebound in the spinal network for locomotion in lamprey. J Neurophysiol. 2011;105:1212–1224. doi: 10.1152/jn.00324.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Person AL, Raman IM. Purkinje neuron synchrony elicits time-locked spiking in the cerebellar nuclei. Nature. 2011;481:502–505. doi: 10.1038/nature10732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kam K, Worrell JW, Ventalon C, Emiliani V, Feldman JL. Emergence of population bursts from simultaneous activation of small subsets of preBötzinger complex inspiratory neurons. J Neurosci. 2013;33:3332–3338. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4574-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vong L, et al. Leptin action on GABAergic neurons prevents obesity and reduces inhibitory tone to POMC neurons. Neuron. 2011;71:142–154. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scott MM, Williams KW, Rossi J, Lee CE, Elmquist JK. Leptin receptor expression in hindbrain Glp-1 neurons regulates food intake and energy balance in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2413–2421. doi: 10.1172/JCI43703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matei V, et al. Smaller inner ear sensory epithelia in Neurog 1 null mice are related to earlier hair cell cycle exit. Dev Dyn. 2005;234:633–650. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kjaerulff O, Kiehn O. Distribution of networks generating and coordinating locomotor activity in the neonatal rat spinal cord in vitro: A lesion study. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5777–5794. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-18-05777.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.