Intentionally deceptive news has co-opted social media to go viral and influence millions. Science and technology can suggest why and how. But can they offer solutions?

In 2010 computer scientist Filippo Menczer heard a conference talk about some phony news reports that had gone viral during a special Senate election in Massachusetts. “I was struck,” says Menczer. He and his team at Indiana University Bloomington had been tracking early forms of spam since 2005, looking mainly at then-new social bookmarking sites such as https://del.icio.us/. “We called it social spam,” he says. “People were creating social sites with junk on them, and getting money from the ads.” But outright fakery was something new. And he remembers thinking to himself, “this can’t be an isolated case.”

Fig. 1.

Fabricated social media posts have lured millions of users into sharing provocative lies. Image courtesy of Dave Cutler (artist).

Of course, it wasn’t. By 2014 Menczer and other social media watchers were seeing not just fake political headlines but phony horror stories about immigrants carrying the Ebola virus. “Some politicians wanted to close the airports,” he says, “and I think a lot of that was motivated by the efforts to sow panic.”

By the 2016 US presidential election, the trickle had become a tsunami. Social spam had evolved into “political clickbait”: fabricated money-making posts that lured millions of Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube users into sharing provocative lies—among them headlines claiming that Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton once sold weapons to the Islamic State, that Pope Francis had endorsed Republican candidate Donald Trump, and (from the same source on the same day) that the Pope had endorsed Clinton.

Social media users were also being targeted by Russian dysinformatyea: phony stories and advertisements designed to undermine faith in American institutions, the election in particular. And all of it was circulating through a much larger network of outlets that spread partisan attacks and propaganda with minimal regard for conventional standards of evidence or editorial review. “I call it the misinformation ecosystem,” says Melissa Zimdars, a media scholar at Merrimack College in North Andover, MA.

Call it misinformation, fake news, junk news, or deliberately distributed deception, the stuff has been around since the first protohuman whispered the first malicious gossip (see Fig. 2). But today’s technologies, with their elaborate infrastructures for uploading, commenting, liking, and sharing, have created an almost ideal environment for manipulation and abuse—one that arguably threatens any sense of shared truth. “If everyone is entitled to their own facts,” says Yochai Benkler, codirector of the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University, echoing a fear expressed by many, “you can no longer have reasoned disagreements and productive compromise.” You’re “left with raw power,” he says, a war over who gets to decide what truth is.

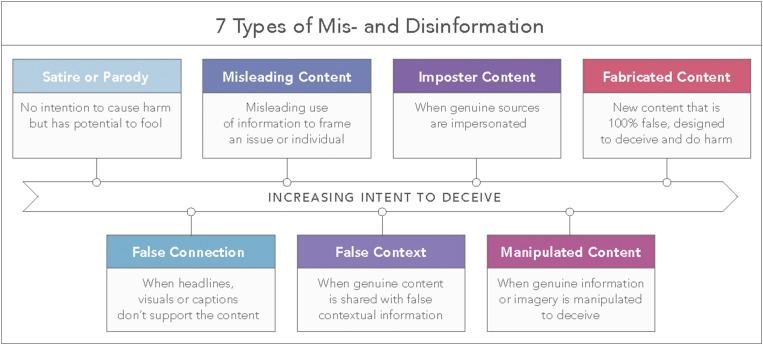

Fig. 2.

“Fake news” has become common parlance in the wake of the 2016 presidential election. But many researchers and observers believe the term is woefully loaded and of minimal use. Not only has President Donald Trump co-opted the term “fake news” to mean any coverage he doesn’t like, but also “the term doesn’t actually explain the ecosystem,” says Claire Wardle, director of research at an international consortium called First Draft. In February, she published an analysis (7) that identified six other tricks of the misinformation game, none of which requires content that’s literally “fake.” Image reproduced with permission from Claire Wardle, modified by Lucy Reading (artist).

If the problem is clear, however, the solutions are less so. Even if today’s artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms were good enough to filter out blatant lies with 100% accuracy—which they are not—falsehoods are often in the eye of the beholder. How are the platforms supposed to draw the line on constitutionally protected free speech, and decide what is and is not acceptable? They can’t, says Ethan Zuckerman, a journalist and blogger who directs the Center for Civic Media at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. And it would be a disaster to try. “Blocking this stuff gives it more power,” he says.

So instead, the platforms are experimenting in every way they can think of: tweaking their algorithms so that news stories from consistently suspect sites aren’t displayed as prominently as before, tying stories more tightly to reputable fact-checking information, and expanding efforts to teach media literacy so that people can learn to recognize bias on their own. “There are no easy answers,” says Dan Gillmor, professor of practice and director of the News Co/Lab at Arizona State University in Tempe, AZ. But, Gillmor adds, there are lots of things platforms as well as science communicators can try.

Tales Signifying Nothing

Once Menczer and his colleagues started to grasp the potential extent of the problem in 2010, he and his team began to develop a system that could comb through the millions of publicly available tweets pouring through Twitter every day and look for patterns. Later dubbed Truthy, the system tracked hashtags such as #gop and #obama as a proxy for topics, and tracked usernames such as @johnmccain as a way to follow extended conversations.

That system also included simple machine-learning algorithms that tried to distinguish between viral information being spread by real users and fake grass-roots movements— “astroturf”—being pushed by software robots, or “bots.” For each account, says Menczer, the algorithms tracked thousands of features, including the number of followers, what the account linked to, how long it had existed, and how frequently it tweeted. None of these features was a dead giveaway. But collectively, when compared with the features of known bots, they allowed the algorithm to identify bots with some confidence. It revealed that bots were joining legitimate online communities, raising the rank of selected items by artificially retweeting or liking them, promoting or attacking candidates, and creating fake followers. Several bot accounts identified by Truthy were subsequently shut down by Twitter.

The Indiana group eventually expanded Truthy into the publicly available Observatory for Social Media: a suite of programs such as Botometer, a tool for measuring how bot-like a Twitter user’s behavior is, and Hoaxy, a tool for visualizing the spread of claims and fact checking.

In retrospect, this kind of exploitation wasn’t too surprising. Not only had the social media platforms made it very cheap and easy, but they had essentially supercharged our human instinct for self-segregation. This tendency, studied in the communication field since the 1960s, is known as selective exposure (1): People prefer to consume news or entertainment that reinforces what they already believe. And that, in turn, is rooted in well-understood psychological phenomena such as confirmation bias—our tendency to see only the evidence that confirms our existing opinions and to ignore or forget anything that doesn’t fit.

From that perspective, a Facebook or Twitter newsfeed is just confirmation bias backed with computer power: What you see when you look at the top of the feed is determined algorithmically by what you and your friends like. Any discordant information gets pushed further and further down the queue, creating an insidious echo chamber.

Certainly, the echo chamber was already well established by the eve of the 2016 election, says Benkler, who worked with Zuckerman on a postelection study of the media ecosystem using MediaCloud, a tool that allowed them to map the hyperlinks among stories from some 25,000 online news sources. “Let’s say that on Facebook, you have a site like End the Fed, and a more or less equivalent site on the left,” he says. Statistically, he says, the groups that are retweeting and linking to posts from the left-leaning site will also be linking to mainstream outlets such as the New York Times or The Washington Post and will be fairly well integrated with the rest of the Internet.

But the sites linking to End the Fed (which describes the US Federal Reserve Bank as “a national counterfeiting operation”) will be much more inward-looking with statistically fewer links to the outside and content that has repeatedly been “validated” by conspiracy sites. It’s classic repetition bias, explains Benkler: “If I’ve seen this several times, it must be true.”

Exposing the Counterfeits

Attempts to excise the junk present platforms with a tricky balancing act. On the one hand, the features being exploited for misinformation—the newsfeed, the network of friends, the one-click sharing—are the very things that have made social media such a success. “When I ask Facebook to change its product, that’s a big ask,” says Gillmor. “They have a huge enterprise based on a certain model.”

Then too, the platforms are loath to set themselves up as arbiters of what is and isn’t true, because doing so would invite a severe political backlash and loss of credibility. “I have some sympathy when they say don’t want to be media companies,” says Claire Wardle, director of research at First Draft, an international consortium of technology companies, news organization, and researchers formed in 2015 to address issues of online trust and truth. “We’ve never had anything like these platforms before. There’s no legal framework to guide them.”

On the other hand, an uncontrolled flood of misinformation threatens to undermine the platforms’ credibility, too. “So they're under huge pressure to be seen doing something,” says Wardle. Witness the shift made by Facebook Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg, she says, from dismissing the influence of fake news as “a pretty crazy idea” just days after the election to announcing (2) three months later that the integrity of information would be one of Facebook’s top priorities going forward. Or witness the discomfort felt by representatives of Facebook, Twitter, and Google at an October 31 Senate hearing. If the platforms were so wonderfully high tech, the senators wondered, why couldn’t they do a better job of vetting the fake news and Russian-backed ads seen by millions—or at least post the kind of corrections that newspapers have been running for generations?

The representatives were noncommittal. But in fact, says Wardle, “all those companies are investing a huge amount to time and talent to come up with AI technology and such to solve the problem.”

Not surprisingly, the platforms are close-mouthed about their exact plans, if only to slow down efforts to game their systems. (Neither Facebook nor Google responded to requests for comment on this story.) But through public announcements they’ve made their basic strategy clear enough.

First is minimizing the rewards for promoting misinformation. A week after the election, for example, both Facebook and Google announced that they would no longer allow blatantly fake news sites to earn money on their advertising networks. Then in May 2017, Facebook announced that it would lower the newsfeed rankings of low-quality information, such as links to ad-choked sites that qualify as clickbait, political or otherwise. But then, how are the newsfeed algorithms supposed to recognize what’s “low quality”?

In principle, says Menczer, the platforms could (and probably do) screen the content of posts using the same kind of machine-learning techniques that the Indiana group used in Truthy. And they could apply similar algorithms to signals from the larger network. For example, is this post being frequently shared by people who have previously shared a lot of debunked material?

But in practice, says Menczer, “you can never have absolutely perfect machine learning with no errors.” So, Facebook and the rest would much rather live with loose algorithms that yield a lot false negatives—letting junk through—than risk using tight algorithms that yield false positives, i.e., rejecting items that aren’t junk, which opens them up to the political-bias accusations or even ridicule. Witness the embarrassment that Facebook endured last year, when rules designed to flag child pornography led it to ban (briefly) the Pulitzer Prize-winning photo of a naked, nine-year-old Vietnamese girl fleeing a napalm attack.

Consumer Culture

A second element of the strategy is to help users evaluate what they’re seeing. Until recently, says Zimdars, social media tried to democratize the news—meaning that the most egregious political clickbait would show up in the newsfeed in exactly the same way as an article from the New York Times or the Washington Post. And that confusion has consequences, according to a 2017 survey (3) carried out by the Pew Research Center: people are much less likely to remember the original source of a news story when they encounter it on social media, via a post, versus when they access the news site directly.

In August, however, Facebook announced that publishers would henceforth have the option to display their logos beside their headlines—a branding exercise that could also give readers a crucial signal about whom to trust.

Since 2014, meanwhile, the Trust Project at Santa Clara University in California, with major funding from Google, has been looking into trust more deeply. Via interviews with users that explored what they valued, the researchers have developed a series of relatively simple things that publishers can do to enhance trust. Examples include clear, prominently displayed information about the publication’s ownership, editorial oversight, fact checking practices, and corrections policy as well as biographical information about the reporters. The goal is to develop a principled way to merge these factors into a simple trust ranking. And ultimately, says Wardle, “newsfeed algorithms could read that score, and rank the more trustworthy source higher.”

Labeling is hardly a cure-all, however: in a study (4) published in September, Yale University psychologists David Rand and Gordon Pennycook found that when users were presented with a newsfeed in which some posts were labeled as “disputed” by fact checkers, it backfired. Users ended up thinking that even the junkiest unflagged posts were more believable—when it was really just a matter of the checkers’ not having the resources to look at everything. “There is some implicit information in the absence of a label,” says Rand—an “implied-truth” effect.

Journalism professor Dietram Scheufele, at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, thinks that a better approach would be to confront confirmation bias directly, so that the newsfeed would be engineered to sometimes include stories outside a user’s comfort zone. “We don’t need a Facebook feed that tells us what is right or wrong, but a Facebook feed that deliberately puts contradictory news in front of us,” he says, although there is no sign that Facebook or any other platform is planning such an initiative.

This leads to the final and arguably most important piece of the strategy: help people become more savvy media consumers and thus lower the demand for dubious news. “If we don’t come at this problem strongly from the demand side, we won’t solve it,” declares Gillmor.

No one imagines that media literacy will be easy to foster, however. It’s one thing to learn how the media works and how to watch out for all the standard misinformation tricks, says Wardle. But it’s quite another to master what Buzzfeed reporter Craig Silverman calls emotional skepticism, which urges users to slow down and check things before sharing them.

Menczer argues that the platforms could help by creating some friction in the system, making it harder to share. Platforms could, for example, block users from sharing an article until after they’d read it or until they had passed a captcha test to prove they were human. “That would filter out a big fraction of the junk,” he says.

There’s no evidence that any platform is contemplating such a radical shift. But Facebook, for one, has been pushing news literacy as a key part of its journalism project (5). Launched in January, it aims to strengthen the company’s ties to the news industry by funding the education of reporters as well as collaborating on innovative news products. Classes in media literacy, meanwhile, are proliferating at every grade level—one much-publicized example being the University of Washington’s Calling Bullshit course, which teaches students how to spot traps such as grossly misleading graphics or deceptive statistics. In Italy, meanwhile, the Ministry of Education launched a digital literacy course in 8,000 high schools starting October 31, in part to help students identify intentionally deceptive news.

Another recent study from Rand and Pennycock (6) also offers some reason for optimism. The researchers gave their subjects a standard test of analytical thinking, the ability to reason from facts and evidence. When the researchers then showed their subjects a selection of actual news headlines, Rand says, “we found that people who are more analytic thinkers are better able to tell real from fake news even when it doesn’t align with their existing beliefs.” Better still, he says, this difference existed regardless of education level or political affiliation. Confirmation bias isn’t destiny. “If we can teach people to think more carefully,” Rand says referring to dubious news content, “they will be better able to tell the difference.”

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Stroud NJ. 2017 Selective exposure theories. Available at www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199793471.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199793471-e-009. Accessed September 28, 2017.

- 2.Zuckerberg M. 2017 Building global community. Available at https://www.facebook.com/notes/mark-zuckerberg/building-global-community/10154544292806634. Accessed October 2, 2017.

- 3.Mitchell A, Gottfried J, Shearer E, Lu K. 2017 How Americans encounter, recall and act upon digital news. Available at www.journalism.org/2017/02/09/how-americans-encounter-recall-and-act-upon-digital-news/. Accessed October 2, 2017.

- 4.Pennycook G, Rand DG. 2017 Assessing the effect of “disputed” warnings and source salience on perceptions of fake news accuracy. Available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3035384. Accessed September 29, 2017.

- 5.Simo F. 2017 Introducing: The Facebook journalism project. Available at https://media.fb.com/2017/01/11/facebook-journalism-project/. Accessed October 2, 2017.

- 6.Pennycook G, Rand DG. 2017 Who falls for fake news? The roles of analytic thinking, motivated reasoning, political ideology, and bullshit receptivity. Available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3023545. Accessed October 9, 2017.

- 7.Wardle C. 2017 Fake news. It’s complicated. Available at https://firstdraftnews.com:443/fake-news-complicated/. Accessed August 25, 2017.