Veselits et al. show that Igβ ubiquitination activates PI3K and the accumulation of PIP3 on BCR-associated endosomal membranes, which is necessary and sufficient for sorting into classical antigen-processing compartments. Surprisingly, proper BCR sorting is critical for endosomal TLR activation yet dispensable for T-dependent humoral immunity.

Abstract

A wealth of in vitro data has demonstrated a central role for receptor ubiquitination in endocytic sorting. However, how receptor ubiquitination functions in vivo is poorly understood. Herein, we report that ablation of B cell antigen receptor ubiquitination in vivo uncouples the receptor from CD19 phosphorylation and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signals. These signals are necessary and sufficient for accumulating phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) on B cell receptor–containing early endosomes and proper sorting into the MHC class II antigen-presenting compartment (MIIC). Surprisingly, MIIC targeting is dispensable for T cell–dependent immunity. Rather, it is critical for activating endosomal toll-like receptors and antiviral humoral immunity. These findings demonstrate a novel mechanism of receptor endosomal signaling required for specific peripheral immune responses.

Introduction

Recognition of polyvalent antigens by the B cell receptor (BCR) initiates two simultaneous processes critical for B cell activation. One is the induction of signaling cascades that modulate transcriptional programs determining cell fate (Kurosaki et al., 2010; Clark et al., 2014). The other is the capture and delivery of antigenic complexes along the endocytic pathway to the MHC class II antigen-presenting compartment (MIIC; Qiu et al., 1994; Ferrari et al., 1997; Clark et al., 2011; Blum et al., 2013). Endocytic trafficking is also necessary for activating, by BCR-captured ligands, TLRs 7 and 9, which take residence in the MIIC after BCR ligation (Chaturvedi et al., 2008; O’Neill et al., 2009; Lee and Barton, 2014). Therefore, BCR endocytic trafficking links signals elicited at the cell surface (signal 1) to costimulatory processes that originate in late endosomes (signal 2; Bretscher and Cohn, 1970).

Signals are initiated through the BCR when Igα and Igβ immunoreceptor tyrosine–based activation motifs are phosphorylated to form a recruitment site for the spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk). Downstream phosphorylation of the B cell linker protein (BLNK or SLP-65; Kabak et al., 2002) forms a platform for assembly of downstream effectors, including Btk, PLCγ2, Nck, Vav, and Grb2 (Herzog et al., 2008; Kurosaki et al., 2010). A particularly important signaling effector is phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), which is required for B cell development (Fruman et al., 1999; Clayton et al., 2002; Ramadani et al., 2010; Clark et al., 2014), regulation of receptor editing (Tze et al., 2005), peripheral B cell maintenance (Srinivasan et al., 2009), and germinal center (GC) responses (Wang et al., 2002; Castello et al., 2013; Sander et al., 2015). There are multiple ways in which PI3K can be activated (Engel et al., 1995; Rickert et al., 1995; Wang et al., 2002; Aiba et al., 2008; Castello et al., 2013; Clark et al., 2014). However, how activation occurs in each functional context is incompletely understood.

Igβ is also inducibly ubiquitinated, and in vitro, this is necessary for sorting internalized BCRs into the MIIC (Zhang et al., 2007). Based on a wealth of in vitro data, ubiquitinated receptors are recognized by components of the endosomal complex required for transport (Raiborg and Stenmark, 2009), which are first recruited to endosomes by inositols phosphorylated at the 3 position, especially phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3; Schmidt and Teis, 2012). Surprisingly, the in vivo significance of antigen receptor ubiquitination and PIP3 in receptor trafficking is largely unexplored.

Within the MIIC, many of the same mechanisms that process antigens into peptides are necessary for activating TLRs 7 and 9 (Lee and Barton, 2014). Linked recognition between BCR and TLR7 or TLR9 is required for anti-RNP and anti-DNA humoral autoimmunity, respectively (Leadbetter et al., 2002; Viglianti et al., 2003; Christensen et al., 2006). TLR7 is also required for humoral immunity to RNA viruses (Koyama et al., 2007), including influenza, whereas TLR9 mediates responses to DNA-containing viruses (Hou et al., 2011).

Targeting the MIIC is dependent on BCR-initiated signals that accelerate receptor internalization (Niiro et al., 2004; Gazumyan et al., 2006; Hou et al., 2006) and enable BCR trafficking to late endosomes (Chaturvedi et al., 2008; Clark et al., 2011). Disruption of proximal signaling pathways, such as what occurs in anergy, blocks both BCR and TLR endocytic transit (Chaturvedi et al., 2008; O’Neill et al., 2009). There is only a partial understanding of the signaling pathways mediating BCR endocytic transit (Chaturvedi et al., 2008; Clark et al., 2011). Furthermore, it is not known whether the signaling mechanisms regulating BCR trafficking are similar or different than those regulating other BCR-dependent development and maturation transitions.

Herein, we use mice expressing an Igβ cytosolic tail mutant (IgβKΔR) to demonstrate that Igβ ubiquitination enables BCRs to enter the MIIC by activating PI3K and generating PIP3 on early endocytic vesicles containing internalized BCR complexes (Murphy et al., 2009; Chaturvedi et al., 2011). Other PI3K-dependent B cell functions were normal in IgβKΔR mice, indicating that Igβ ubiquitination mediates a highly specific mechanism of PI3K activation required for one BCR-dependent function: endocytic sorting.

Results

B cell development in IgβKΔR mice

Gene targeting was used to derive C57BL/6 homozygous mice in which the codons encoding the three Igβ cytosolic lysines were mutated to encode arginines (IgβKΔR; Fig. S1 A). These mice were then crossed to mice expressing FLP1 recombinase to delete the neomycin gene (Neo). Proper gene targeting and Neo deletion were confirmed by PCR of genomic DNA (Fig. S1 B). mRNA was isolated from WT and homozygous IgβKΔR (hereafter IgβKΔR) splenic B cells, amplified by PCR, and sequenced to confirm targeted mutations (Fig. S1, C and D). Immunoprecipitating the Igα/Igβ heterodimer from WT and IgβKΔR splenic B cells, followed by immunoblotting sequentially with ubiquitin- and Igβ-specific antibodies demonstrated that WT Igβ was ubiquitinated in the resting BCR and that this increased the resulting BCR clustering. In contrast, neither the resting nor clustered IgβKΔR BCR was detectably ubiquitinated (Fig. S1 E).

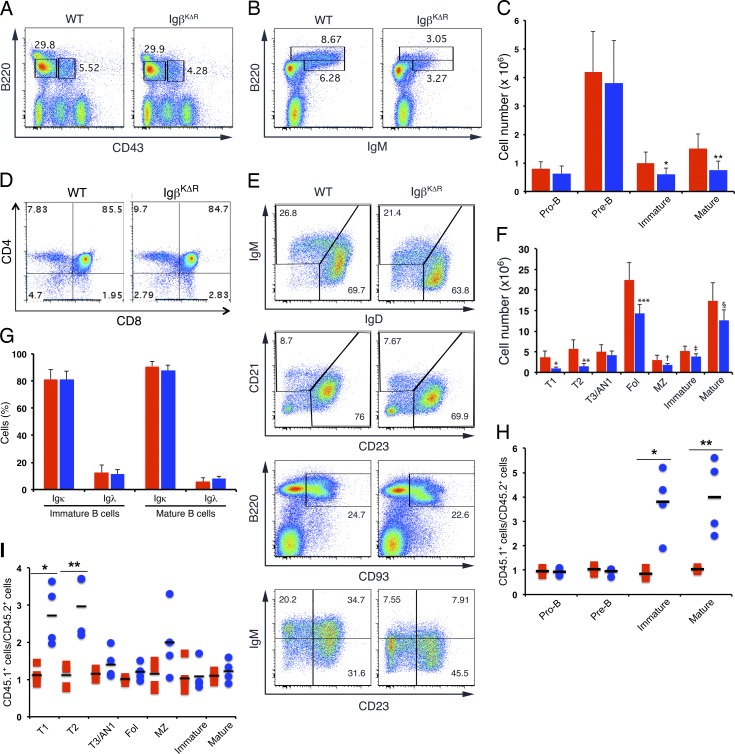

To explore the in vivo consequences of Igβ ubiquitination, bone marrow (BM) was harvested from WT and IgβKΔR mice, stained with antibodies specific for B220, CD43, and IgM, and then examined by flow cytometry (Fig. 1, A–C). Early B cell development appeared normal with no significant differences in the pro–B cell (B220+CD43+IgM−) and pre–B cell (B220+CD43−IgM−) compartments of WT and IgβKΔR mice. However, the numbers of immature (B220intermedCD43−IgM+) and mature (B220highCD43−IgM+) B cells in IgβKΔR mice were reduced approximately twofold. IgM surface densities on immature and mature B cells were also reduced, with only a few cells expressing high levels of IgM. Mean fluorescence intensity of surface IgM staining on WT and IgβKΔR immature B cells was 2,497 ± 255 and 1,305 ± 62, respectively (P = 0.0001). As expected, thymic T cell development was normal in IgβKΔR mice (Fig. 1 D).

Figure 1.

Selective defect in late B cell development in IgβKΔR mice. (A–C) BM cells from WT and IgβKΔR mice were isolated, stained with antibodies specific for B220, CD43, and IgM, and analyzed by flow cytometry (A and B). Total numbers of each population (C) are provided for WT (red) and IgβKΔR (blue) mice; error bars indicate mean ± SD. *, P = 0.0167; **, P = 0.0022 (n = 3). (D) Thymic CD3+ lymphocytes were analyzed by flow cytometry for CD4 and CD8 expression (n = 3 mice). (E and F) Splenic B cells from the indicated mice were stained with antibodies specific for B220, IgM, IgD, CD21, CD23, and CD93 and then analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometric plots are shown in E, and total numbers of each population from WT (red) and IgβKΔR (blue) are shown in F. *, P = 0.0046; **, P = 0.0021; ***, P = 0.0044; †, P = 0.0009; ‡, P = 0.0012; §, P = 0.0033 (n = 4 mice per condition). (G) Flow cytometry of WT (red) and IgβKΔR (blue) BM immature and mature B cells stained for Igκ and Igλ (n = 3). (H and I) BM from WT CD45.1 mice was mixed 50:50 with WT CD45.2 (red) or IgβKΔR CD45.2 (blue) BM and then transferred into irradiated WT CD45.1 mice. After 8–9 wk, BM (*, P = 0.006; **, P = 0.009; H) and spleen (*, P = 0.003; **, P = 0.002; I) were analyzed by flow cytometry. Each point represents one mouse. Horizontal lines represent means. MZ, marginal zone. Fol, follicular B cells.

In the periphery, transitional B cell populations (T1, CD93+IgM+CD23−; and T2, CD93+IgM+CD23+; Merrell et al., 2006) were significantly diminished. However, later developmental stages, including T3/AN1 (CD93+IgMlowCD23+), splenic immature (B220+IgM+IgD−), and mature (B220+IgM+IgD+) B cell populations, were only mildly decreased (Fig. 1, E and F). There was a proportional decrease in the number of follicular (B220+CD21loCD23hi) and marginal zone B cells (B220+CD21hiCD23lo). IgM surface densities on splenic immature IgβKΔR B cells were only slightly diminished compared with WT (1.3-fold), whereas IgD surface densities were normal. Therefore, IgβKΔR mice do not have a substantial defect in BCR expression in the periphery.

In immature BM B cells, changes in receptor editing are usually associated with changes in the fraction of cells expressing Igλ (Gay et al., 1993; Tiegs et al., 1993). However, as demonstrated in Fig. 1 G, the frequencies of Igλ+ cells in IgβKΔR, WT immature, and mature B cell populations were similar. This suggests that receptor editing was normal in IgβKΔR mice.

To determine whether the observed phenotypes were cell intrinsic and/or influenced by lymphopenia, we performed competitive BM chimera reconstitutions. Sublethally irradiated Rag2−/−II2rg−/− mice were reconstituted with WT (CD45.1) BM mixed 50:50 with either IgβKΔR (CD45.2) or WT (CD45.2) BM. 8–9 wk after reconstitution, BM and spleens were harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 1 H, IgβKΔR and WT BM were equally efficient at reconstituting the pro– and pre–B cell populations. In contrast, IgβKΔR BM was about a fourfold less efficient than WT BM in reconstituting the immature and mature B cell pools. In the periphery, IgβKΔR BM was less fit to reconstitute the transitional (T1 and T2) and marginal zone B cell compartments. In contrast, both WT and IgβKΔR BM equally reconstituted An1/T3, follicular, immature, and mature B cell compartments (Fig. 1 I). These data indicate that IgβKΔR mice have a defect in late B lymphopoiesis that recovers to normal levels in the periphery.

BCR capping and entry into the MIIC require Igβ ubiquitination

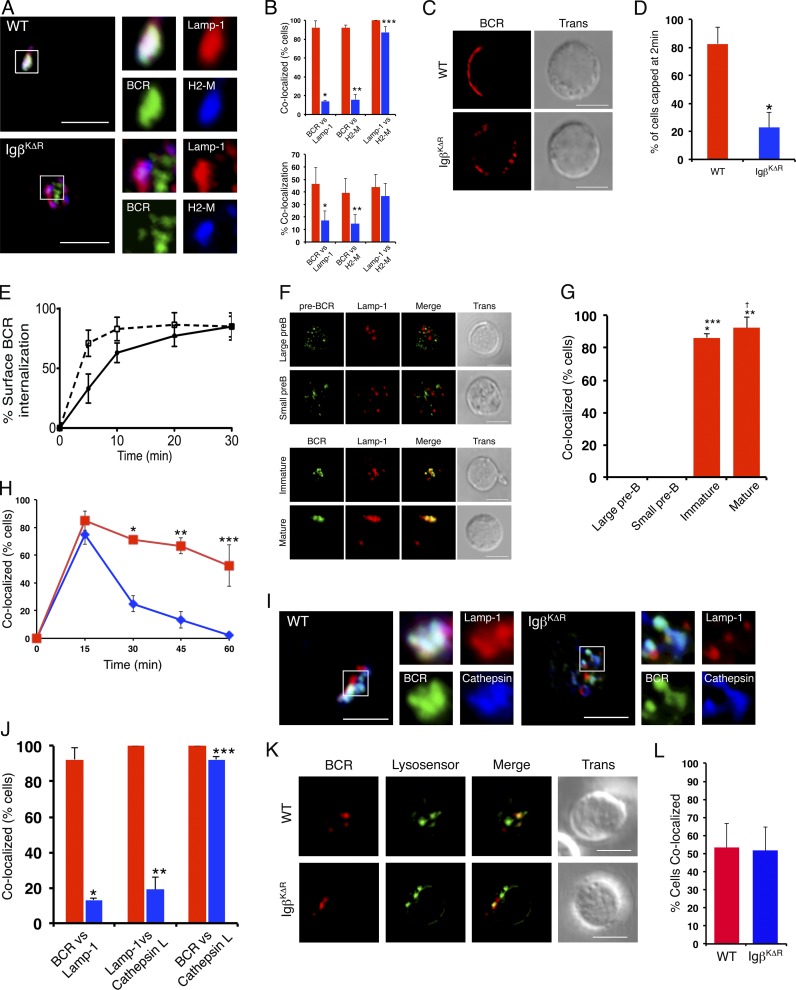

Cell line studies suggested that Igβ ubiquitination was required for targeting the MIIC (Zhang et al., 2007). Therefore, WT and IgβKΔR B splenocytes were stimulated in culture through the BCR with FITC-conjugated anti-IgG and -IgM (heavy chain and light chain [H+L]) F(ab)2 antibodies for up to 30 min. Cell aliquots were then fixed, stained with Lamp-1– and H2-M–specific antibodies, and visualized by confocal microscopy. As demonstrated (Fig. 2, A and B), IgβKΔR BCRs were excluded from H2-M+Lamp-1+ MIIC late endosomes.

Figure 2.

Defective capping and MIIC targeting of IgβKΔR BCRs. (A and B) WT and IgβKΔR splenocytes were stimulated with FITC-conjugated IgG and IgM (H+L) F(ab)2 antibodies for 30 min in vitro, then fixed, stained with antibodies specific for Lamp-1 and H2-M, and visualized by confocal microscopy. Representative images. Quantitation of WT (red) or IgβKΔR (blue) samples (n = 3; B) based on percentage of cells with >25% overlap between the indicated markers (top) or percent colocalization of total immunofluorescence (Manders’ Coefficient; bottom). Top: *, P = 1.3 × 10−12; **, P = 3.6 × 10−15; ***, P = 0.0061. Bottom: *, P = 4.0 × 10−5; **, P = 10−6. (C and D) Cells were stimulated as in A for 2 min, fixed, and visualized by confocal microscopy. Representative images (n = 3) provided in C with quantitation of percentage of cells displaying capping provided in D; *, P = 1.4 × 10−5. (E) Internalization of BCRs from surface of WT (closed circles) or IgβKΔR (open squares) B splenocytes after stimulation with PE-conjugated IgG- and IgM (H+L)-specific F(ab)2 antibodies; P = 0.0291 (two-way ANOVA; n = 3). (F and G) WT BM large pre–B cell, small pre–B cell, immature, and mature B cell populations were isolated by flow cytometry. Pre-BCRs were stimulated with biotin-conjugated anti-SL156, and BCRs were stimulated FITC-conjugated IgG and IgM (H+L) F(ab)2 antibodies, respectively, for 30 min at 37°C, and then fixed and counterstained with anti–Lamp-1 antibodies. The pre-BCR was stained with rabbit antibiotin, followed by donkey anti–rabbit Alexa Fluor 488, and all cells were visualized by confocal microscopy. Representative images are provided in F, whereas the fraction of each cell population demonstrating >25% colocalization between the receptor and Lamp-1 are provided in G (n = 3). *, P = 8.10−10 versus large pre–B; **, P = 9.8 × 10−16 versus large pre–B; ***, P = 1.03 × 10−9 versus small pre–B; †, P = 1.4 × 10−15 versus small pre–B. (H) WT (red) or IgβKΔR (blue) B splenocytes were stimulated with FITC-conjugated IgG- and IgM (H+L)-specific F(ab)2 antibodies for the indicated times in vitro, fixed, and stained with EEA1-specific antibodies, and the percentage of cells demonstrating >25% BCR colocalization with EEA1 was plotted as a function of time. *, P = 0.293; **, P = 6.22 × 10−6; ***, P = 0.0004. (I and J) WT or IgβKΔR B splenocytes were stimulated with FITC-conjugated IgG- and IgM (H+L)-specific F(ab)2 antibodies for 30 min in vitro, fixed, and stained with antibodies specific for Lamp-1 and Cathepsin L. Representative images. Quantitative assessment of colocalization of the indicated markers for WT (red) or IgβKΔR (blue) cells (J; n = 3). *, P = 1.16 × 10−16; **, P = 4.92 × 10−12; ***, P = 0.0010. (K and L) Cells were loaded with 1 µM LysoSensor and then stimulated with Texas red–conjugated IgG- and IgM (H+L)-specific F(ab)2 antibodies for 30 min. (K) Cells were visualized by confocal microscopy. (I) Provided are the percentage of cells demonstrating >25% colocalization. WT (red bar) and IgβKΔR (blue bar); error bars represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Bars, 5 µm.

Examination of an earlier time point after 2-min stimulation demonstrated that IgβKΔR BCRs did not cap normally (Fig. 2, C and D). Though ∼80% of WT cells formed a single cap after BCR clustering, this was observed in only 20% of IgβKΔR splenocytes. Rather, multiple patches of IgβKΔR BCRs were usually distributed across the cell surface.

In cell lines, Igβ ubiquitination is dispensable for BCR internalization (Zhang et al., 2007). Indeed, IgβKΔR BCRs were internalized more rapidly than WT BCRs after receptor cross-linking (Fig. 2 E). These data indicate that Igβ ubiquitination is required for both BCR capping and sorting into the MIIC. Furthermore, it appeared to modulate early BCR internalization.

In IgβKΔR mice, pre-BCR–mediated development was normal, whereas BCR-mediated selection into the immature B cell pool was impaired. We therefore examined whether endocytic trafficking of the pre-BCR and BCR was also different. Large and small pre–B cells, immature B cells, and mature B cells were isolated from WT BM by flow cytometry. The pre-BCR was labeled on ice with the biotinylated antibody SL156, whereas BCRs on immature and mature B cells were labeled with FITC-conjugated anti-IgG and -IgM (H+L) F(ab)2 antibodies. Samples were then warmed to 37°C for 30 min, fixed, and stained (Fig. 2, F and G). As demonstrated by confocal microscopy, internalized pre-BCRs were completely excluded from Lamp-1+ late endosomes. In contrast, BCRs on immature and mature cells colocalized with late endosomes to a similar degree as endocytosed BCRs on splenic B cells.

We next examined early BCR endocytic sorting. Internalized IgβKΔR BCRs initially targeted EEA1+ early endosomes similarly to WT BCRs (Fig. 2 H). However, IgβKΔR BCRs left this compartment much more rapidly than WT BCRs. In B lymphocytes, terminal lysosomes do not contain Lamp-1 (Li et al., 2002). Indeed, IgβKΔR BCRs rapidly targeted a Lamp-1−Cathepsin L+ (Fig. 2, I and J) and acidic (Fig. 2 K) compartment. These data indicate that in the absence of Igβ ubiquitination, ligated BCR complexes are rapidly internalized and target terminal lysosomes.

Efficient MIIC targeting is dispensable for T-dependent humoral immunity

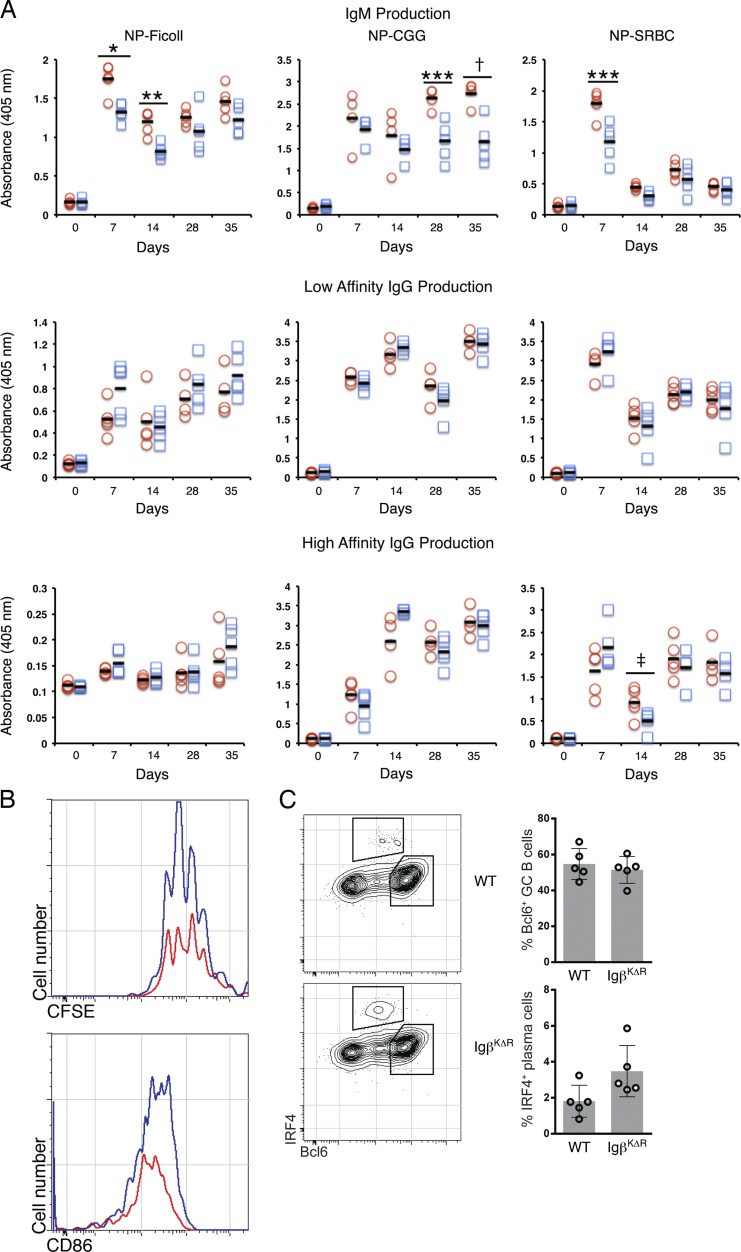

Numerous in vitro studies associate BCR endocytic trafficking to the MIIC with peptide loading of MHC class II and eliciting T cell help (Qiu et al., 1994; Siemasko et al., 1999; Chen and Jensen, 2008; Clark et al., 2011). To examine the in vivo functions of MIIC targeting, WT and IgβKΔR mice were immunized with both T-dependent (NP conjugated to either chicken gamma globulin [CGG], Np-CGG; or NP conjugated to sheep RBCs [SRBCs], NP-SRBCs) and T-independent (NP-Ficoll) antigens intraperitoneally at day 0 and again at day 21. Serum was collected at various time points up to 35 d after initial immunization and assayed by ELISA for NP-specific IgM, as well as low- and high-affinity NP-specific IgG.

Remarkably, humoral immune responses to NP were relatively similar in WT and IgβKΔR mice (Fig. 3 A). There was a modest decrease in titers of IgM to NP in response to NP-Ficoll at days 7 and 14, NP-CGG at days 28 and 35, and NP-SRBCs at day 7. Low-affinity IgG immune responses were similar at all time points, and high-affinity IgG immunity was similar except for a modest decrease in the NP-SRBC responses at day 14.

Figure 3.

Normal T-dependent and T-independent humoral immunity in IgβKΔR mice. (A) WT (open red circles) or IgβKΔR (open blue squares) mice were immunized with T-independent (NP-Ficoll) or T-dependent (NP-CGG or NP-SRBC) antigens, and sera were assayed for NP-specific IgM antibodies (top) and either low-affinity (middle) or high-affinity (bottom) IgG antibodies by ELISA on the indicated days (each symbol represents assay from one mouse). *, P = 0.002; **, P = 0.001; ***, P = 0.005; †, P = 0.004; ‡, P = 0.05. Horizontal lines represent means. (B and C) WT MD4 or IgβKΔRxMD4 were labeled with CFSE and transferred along with HEL-SRBC into B6.SJL-PtprcaPepcb/BoyJ mice. (B) Spleens were harvested 3 d after transfer and analyzed by flow cytometry (n = 5 each group). (C) Spleens were harvested 6 d after transfer/immunization and analyzed by flow cytometry. Individual mice indicated in bar graph (right). Error bars represent mean ± SD.

To better understand early humoral immunity to T-dependent antigens, IgβKΔR mice were crossed to mice expressing a BCR specific for hen egg lysozyme (HEL; MD4). HEL-specific B cells were sorted from WT×MD4 and IgβKΔR×MD4 mice, labeled with CFSE, and transferred into CD45.1 (B6.SJL-PtprcaPepcb/BoyJ) mice. Mice were simultaneously challenged with HEL conjugated to SRBCs. After 3 d, spleens were harvested, labeled with CD86, and assayed by flow cytometry. As seen in Fig. 3 B, dilution of CFSE in HEL-binding WT×MD4 and IgβKΔR×MD4 mice was similar. In addition, both populations up-regulated CD86 (Fig. 3 B). After 6 d, intracellular staining of HEL-binding splenic B cells revealed that both populations up-regulated IRF4 and BCL6 (Ochiai et al., 2013) to a similar degree (Fig. 3 C). In aggregate, these data indicate MIIC targeting is not required for primary T-dependent and T-independent humoral immunity.

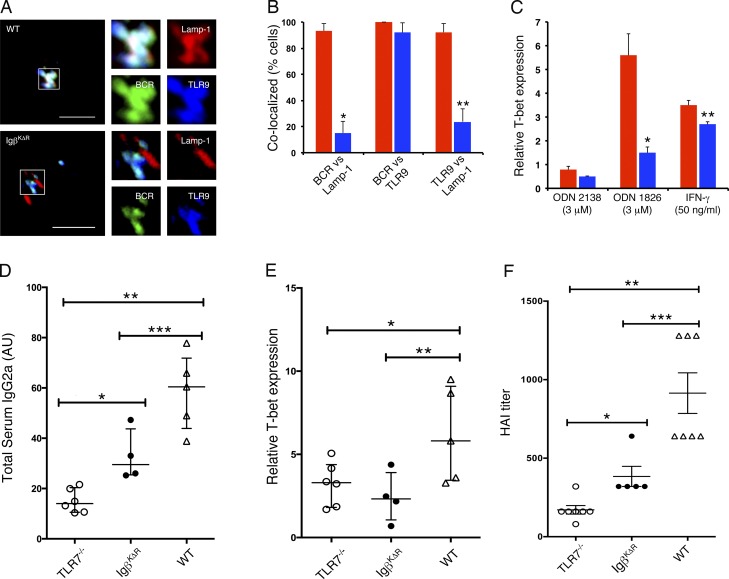

BCR targeting to MIIC required for endocytic TLR activation

Confocal microscopy of WT splenic B cells demonstrated that ligated BCRs were rapidly delivered to TLR9+Lamp-1+ late endosomes (Fig. 4, A and B). In contrast, in IgβKΔR splenic B cells, endocytosed BCRs colocalized with TLR9 but were excluded from Lamp-1+ late endosomes. These results are similar to those observed in anergic B cells (O’Neill et al., 2009) and suggest that endocytosed BCRs traverse through a TLR9+ compartment before entering the MIIC.

Figure 4.

Diminished BCR-dependent activation of endosomal TLRs. (A and B) WT and IgβKΔR splenocytes were stimulated with FITC-conjugated IgG- and IgM (H+L)-specific F(ab)2 antibodies for 30 min in vitro and then fixed, stained with antibodies specific for Lamp-1 and TLR9, and visualized by confocal microscopy. Representative images. Bars, 5 µm (A). Corresponding quantitation of WT (red) or IgβKΔR (blue) samples (n = 3); *, P = 1.3 × 10−15; **, P = 4.4 × 10−8 (B). (C) In vitro assay of T-bet induction in response to ODN 1826 or control ODN (2138) targeted through the BCR (n = 3); *, P = 0.004; **, P = 0.0003. (D and E) The indicated mouse strains were immunized with heat-inactivated influenza virus, boosted at day 21, and serum and splenic B cells were assayed at day 42. (D) IgG2a influenza-specific titers; *, P = 0.0054; ** P < 0.0001; ***, P = 0.0238. (E) Corresponding expression of T-bet mRNA in splenic B cells; *, P = 0.0484; **, P = 0.00507. (F) Serum hemagglutinin inhibition assay in response to influenza infection, day 27; *, P = ns; **, P < 0.0001; ***, P = 0.0034. For D–F, each symbol represents one mouse. Significance was determined by ANOVA in combination with Bonferroni multiple comparison test. P-values as indicated or **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001. Error bars represent mean ± SD.

When a TLR9 ligand (ODN 1826) was targeted to BCRs on WT splenic cells, there was a robust induction of the transcription factor T-box expressed in T cells (T-bet), a target downstream of TLR9 (Fig. 4 C; O’Neill et al., 2009). In contrast, in IgβKΔR splenic B cells BCR-targeted ODN 1826 induced T-bet poorly. Both WT and IgβKΔR splenic B splenocytes strongly expressed T-bet in response to IFNγ and not to a control oligonucleotide (ODN 2138). These data suggest that Igβ ubiquitination is required for coupling BCR antigen recognition to endocytic TLR activation.

To test the importance of Igβ ubiquitination for TLR activation in vivo, WT, Tlr7−/−, and IgβKΔR mice were immunized and then boosted 21 d later with inactive influenza virus particles (Koyama et al., 2007). Comparison of serum influenza-specific IgG2a responses revealed that Tlr7−/− mice had low titers compared with WT mice (Fig. 4 D). Titers in IgβKΔR mice were intermediate and significantly lower than WT titers. Differences in the expression of T-bet in splenic B cells were more striking with both Tlr7−/− and IgβKΔR splenocytes having low and comparable levels of T-bet expression compared with WT controls (Fig. 4 E).

We then challenged WT, Tlr7−/−, and IgβKΔR mice with influenza A virus. 27 d after infection, peripheral blood was assayed for neutralizing titers of antihemagglutinin antibodies. As demonstrated, antihemagglutinin antibody titers in IgβKΔR and Tlr7−/− mice were similar, with both being significantly less than that observed in WT mice (Fig. 4 F). These data suggest that targeting the BCR to the MIIC is more important for TLR-dependent than T cell–dependent primary humoral immunity.

Igβ ubiquitination–mediated PI3K activation regulates endocytic sorting

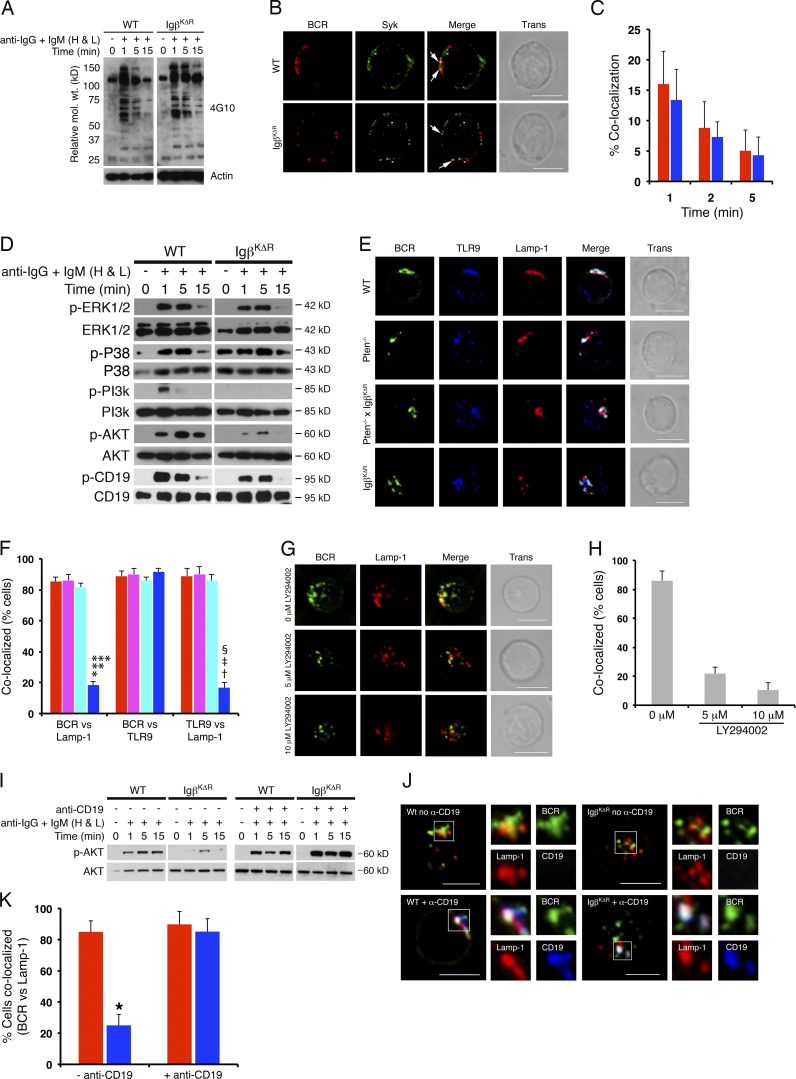

BCR-dependent signals enable the coordinated delivery of both the BCR and TLR9 to the MIIC (Chaturvedi et al., 2008; O’Neill et al., 2009). Therefore, we next determined whether defects observed in IgβKΔR mice were associated with differences in BCR signaling. Stimulation of B splenocytes in vitro followed by immunoblotting of total cell lysates indicated that BCR-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of total cellular proteins was similar in WT and IgβKΔR cells (Fig. 5 A). Furthermore, stimulation of both WT and IgβKΔR cells led to rapid recruitment of Syk to surface BCR complexes (Fig. 5, B and C; Hou et al., 2006). These data indicate that proximal tyrosine kinase activation through IgβKΔR BCRs is intact.

Figure 5.

PI3K-mediated entry into MIIC. (A) WT or IgβKΔR B splenocytes were stimulated with IgG- and IgM (H+L)-specific F(ab)2 antibodies for the indicated times, and total cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antiphosphotyrosine antibodies. Representative of three independent experiments. (B and C) WT or IgβKΔR splenocytes were stimulated with Texas red–labeled anti-IgG and -IgM (H+L) F(ab)2 antibodies for up to 5 min and then fixed, stained with antibodies to Syk, and visualized by confocal microscopy. Representative images provided in B. White arrows denote regions of colocalization. 1-min stimulation with percent colocalization (Manders’ coefficient) between WT (red) or IgβKΔR (blue) BCR and Syk as a function of time after stimulation (C; n = 3). (D) WT or IgβKΔR B splenocytes (106 cells per sample) were stimulated with IgG- and IgM (H+L)-specific F(ab)2 antibodies for the indicated times, and total cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. Each panel is representative of three independent experiments. (E and F) Splenocytes from WT (red), Pten−/− (purple), Pten−/−xIgβKΔR (light blue), and IgβKΔR (dark blue) mice were stimulated with FITC-conjugated IgG- and IgM (H+L)-specific F(ab)2 antibodies for 30 min in vitro and then fixed, stained with antibodies specific for Lamp-1 and TLR9, and visualized by confocal microscopy. Representative images (E) and quantitation of samples (n = 3). *, P = 0.0004; †, P = 0.0016 versus WT; **, P = 0.0004; ‡, P = 0.0023 versus Pten−/−; ***, P = 0.0002; §, P = 0.0014 versus Pten−/−xIgβKΔR (F). (G and H) WT splenocytes were treated with LY294002, stimulated, and visualized by confocal microscopy as above. (I) WT or IgβKΔR splenic B cells stimulated with IgG- and IgM (H+L)-specific F(ab)2 antibodies in the presence or absence of CD19 cross-linking for the indicated times. Total cell lysates blotted as indicated (n = 3). (J and K) Confocal microscopy of cells stimulated for 30 min as in I and stained with the indicated antibodies. Represented images (J) and quantitation across three experiments (K; *, P = 0.0014). Bars, 5 µm. Approximate molecular weight is shown. Error bars represent mean ± SD.

We next examined downstream signaling pathways in IgβKΔR splenocytes. BCR-induced phosphorylation of the MAP kinases ERK and p38 was similar in WT and IgβKΔR splenocytes (Fig. 5 D). In contrast, inductive phosphorylation of the PI3K subunit p85α was abolished in IgβKΔR splenocytes, and AKT phosphorylation was severely attenuated. This was associated with diminished CD19 phosphorylation after BCR ligation in IgβKΔR splenocytes (Carter and Myers, 2008).

We next determined whether diminished PI3K activation contributed to defects observed in IgβKΔR mice. Therefore, IgβKΔR mice were crossed sequentially with mice expressing the Cre recombinase in the Cd19 locus and then with mice containing a floxed allele of Pten. Deletion of Pten in WT mice did not increase numbers of immature and mature BM cells in either WT or IgβKΔR mice (Fig. S2 A). Furthermore, deletion of Pten did not enhance BCR surface densities on IgβKΔR immature B cells (Fig. S2 B). These data suggest that the observed defect in late B cell development is not caused by defective PI3K activation.

To determine the role of PI3K activation in endocytic trafficking in vivo, WT, IgβKΔR, and IgβKΔRCD19crePtenfl/fl B splenocytes were stimulated through the BCR for 30 min and then imaged by multicolor confocal microscopy as described in Materials and methods. As demonstrated in Fig. 5 (E and F), deletion of Pten reconstituted endocytic trafficking of IgβKΔR BCRs into Lamp-1+TLR9+ late endosomes. Conversely, preincubation of WT splenic B cells with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 blocked entry of ligated BCRs into Lamp-1+TLR9+ late endosomes (Fig. 5, G and H). These data suggest that Igβ ubiquitination enables BCR and TLR endocytic trafficking by activating PI3K (O’Neill et al., 2009). Interestingly, deletion of Pten did not reconstitute T-bet induction in IgβKΔR B splenocytes (not depicted). Therefore, in addition to PI3K activation, Igβ ubiquitination likely mediates other processes required to couple BCR recognition to TLR activation.

Defective activation of PI3K–AKT was associated with diminished CD19 phosphorylation, which is a well-described signaling intermediate of BCR-dependent PI3K activation (Carter and Myers, 2008). Indeed, cross-linking of the BCR and CD19 induced robust AKT phosphorylation in IgβKΔR splenocytes (Fig. 5 I). In contrast, CD19 cross-linking did not substantially enhance AKT phosphorylation in WT cells. Furthermore, cross-linking of the BCR and CD19 on IgβKΔR splenocytes rescued BCR endocytic trafficking to Lamp-1+ late endosomes (Fig. 5, J and K). These data suggest that Igβ ubiquitination is required to couple the BCR to efficient CD19-mediated PI3K activation.

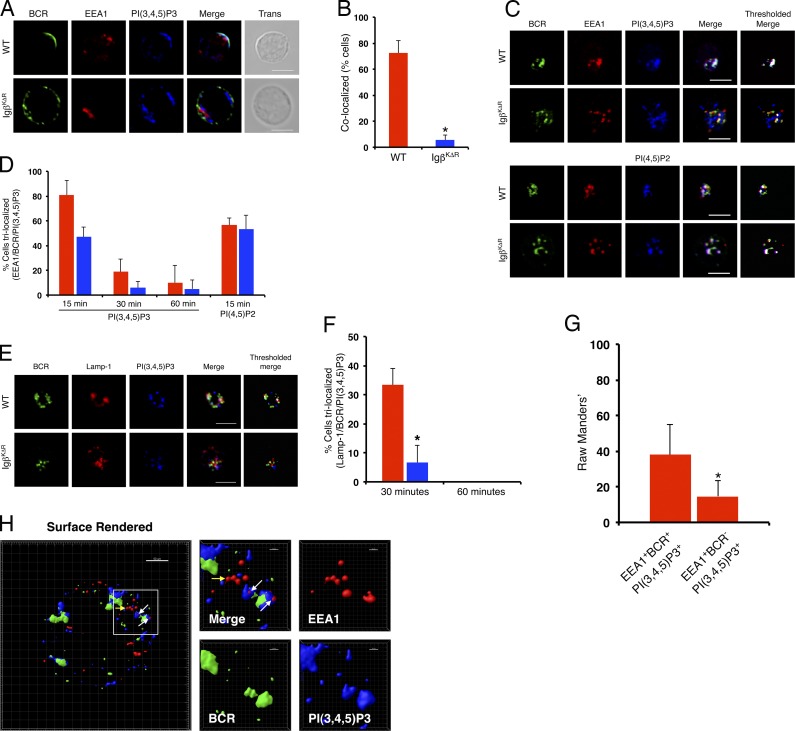

Igβ ubiquitination enhances PIP3 on endosomes

Phosphorylation of phosphatidylinositols by PI3K on endosomal membranes assembles effectors of endocytic trafficking required for vesicular sorting (Schmidt and Teis, 2012). Indeed, clustering of WT BCRs induced a rapid accumulation of PIP3 with the BCR at the plasma membrane after 2 min (Fig. 6, A and B). In contrast, there was little accumulation of PIP3 with IgβKΔR BCRs. At 15 min after stimulation, both the WT and IgβKΔR BCRs target early endosomes. However, accumulation of PIP3 on BCR-targeted EEA1+ early endosomes was much more robust in WT cells (Fig. 6, C and D). In contrast, there was no difference in colocalization of WT and IgβKΔR BCRs with PI (4,5)-diphosphate (PIP2). The difference in PIP3 and BCR colocalization at early endosomes persisted up to 60 min (Fig. S3 A). The WT BCR colocalized with PIP3 on Lamp-1+ late endosomes at 30 min, and this was greatly diminished in IgβKΔR B cells (Fig. 6, E and F). However, the degree of colocalization of WT BCR and PIP3 on late endosomes was less than that observed in early endosomes and was not detectable in this assay by 60 min (Fig. 6 F and Fig. S3 B).

Figure 6.

Igβ ubiquitin–dependent endosomal PIP3. (A–F) Splenocytes from WT or IgβKΔR mice were stimulated with FITC-conjugated IgG- and IgM (H+L)-specific F(ab)2 antibodies for the indicated times, then fixed, stained with antibodies specific for Lamp-1, EEA1, and PIP3, and visualized by confocal microscopy. Representative images from 2 min (A), and quantitation of samples (n = 3); *, P = 2.6 × 10−5 (B). Representative images from 15 min of cells with EEA1 (C), and quantitations (n = 3; *, P ≤ 0.05; D). Representative images of cells treated as in C stained with Lamp-1 (E) with quantitations in F (n = 3; *, P = 0.0048). Quantitation of BCR+ and BCR−EEA1+ early endosomes containing PIP3 (n = 3). *, P > 0.0001 (G). (H) Splenocytes from WT mice were stimulated as above with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated IgG- and IgM (H+L)-specific F(ab)2 antibodies for 15 min, then fixed and stained with antibodies for EEA1 and PIP3, and then visualized by superresolution confocal microscopy. White arrows indicate trilocalization of BCR+EEA1+PIP3+ vesicles, and the yellow arrow indicates BCR−EEA1+PIP3 vesicles. Bars, 5 µm. Error bars represent mean ± SD.

The aformentioned data suggested that PIP3 accumulated primarily on those endocytic vesicles directly targeted by the BCR. Indeed, analysis of BCR+ and BCR− EEA1+ early endosomes 15 min after stimulation revealed that PIP3 was primarily on BCR+ vesicles (Fig. 6 G). To better examine the spatial relationships between the BCR and PIP3, WT cells were stimulated for 15 min, stained as above and imaged using superresolution confocal microscopy, which provided 20-nm x–y axis resolution. As demonstrated (Fig. 6 H and Fig. S3 C), only those EEA1+ vesicles that contained internalized BCR complexes also had detectable levels of PIP3. Furthermore, PIP3 was demonstrable only on that portion of EEA1+ vesicles containing BCR complexes (Fig. 6 H, right). These data indicate a direct role for the BCR, and Igβ ubiquitination, in PIP3 accumulation on early endosomes.

Discussion

The canonical model of antigen receptor signaling is one in which immunoreceptor tyrosine–based activation motif phosphorylation recruits and activates proximal tyrosine kinases, which assemble signalosomes and drive downstream signaling cascades. We now demonstrate that receptor ubiquitination also contributes to signaling by efficiently coupling the BCR to CD19-dependent PI3K activation and the generation of PIP3 on endosomal membranes critical for proper receptor sorting. These data both reveal a novel mechanism of receptor signaling and demonstrate how the BCR can deliver signals to endosomal compartments critical for MIIC targeting.

Endosomal signaling is now recognized to be common and necessary to couple receptor complexes to specific signaling pathways and functions (Su et al., 2006; Murphy et al., 2009; Chaturvedi et al., 2011). However, the mechanisms of endosomal signaling have remained largely unknown. Our data demonstrate endosomal signaling. Remarkably, Igβ ubiquitin–dependent PIP3 accumulation was very local, being restricted to those membrane surfaces containing BCR complexes. This likely drives the assembly of endosomal complexes required for transport (Raiborg and Stenmark, 2009; Vanhaesebroeck et al., 2010) and the sorting of the BCR, but not other receptors, along the endocytic pathway. This spatially restricted signaling mechanism is in contrast to the BCR-initiated kinase cascades that propagate through the cytosol to activate nuclear transcriptional programs (Kurosaki et al., 2010).

PI3K activation by the resting BCR regulates receptor editing (Tze et al., 2005; Verkoczy et al., 2007) and maintains peripheral B cell populations (Srinivasan et al., 2009). Both of these functions appeared normal in IgβKΔR mice. Furthermore, primary T-dependent immune responses, which occur in GCs and require PI3K (Clayton et al., 2002; Jou et al., 2002; Omori and Rickert, 2007; Ramadani et al., 2010), were intact. For B cell development and peripheral responses, several mechanisms of PI3K activation have been described, many with very specific functions (Engel et al., 1995; Rickert et al., 1995; Wang et al., 2002; Aiba et al., 2008; Castello et al., 2013; Clark et al., 2014). Igβ ubiquitination appears to be yet another example in which the mechanism and context of PI3K activation dictate cellular responses.

Likewise, the effects on CD19-dependent functions were very restricted. CD19 is required for initiating GC responses, whereas CD19-dependent PI3K activation is required for propagating the GC reaction (Carter and Myers, 2008). Both were normal in IgβKΔR mice. This could be because BCR-dependent CD19 phosphorylation was only partially attenuated in IgβKΔR splenocytes. Alternatively, Igβ ubiquitin–independent mechanisms of CD19 activation might dominate in GC responses (Carter and Myers, 2008).

Efficient MIIC targeting was dispensable for T-dependent humoral immunity. Although this was surprising, it may reflect the underlying biology of MHC class II trafficking and peptide loading (Blum et al., 2013; Roche and Furuta, 2015). From the trans-Golgi network, MHC class II can either target the endocytic pathway directly or indirectly via the plasma membrane. This ensures that most endocytic compartments contain MHC class II (Blum et al., 2013). In vitro studies have revealed that antigens can be productively processed and loaded onto MHC class II in multiple early and late endosomal compartments (Harding et al., 1990, 1992; Castellino and Germain, 1995; Griffin et al., 1997; Pathak and Blum, 2000). In fact, many T cell epitopes are destroyed in late endosomal compartments by excessive proteolysis (Manoury et al., 2002; Delamarre et al., 2005). Our findings indicate that alternative sites of antigen processing, distinct from the MIIC, are functional and important.

Normal GC responses and intact BCR proximal signaling in IgβKΔR splenocytes indicate that most BCR-dependent functions remain intact in IgβKΔR mice. Furthermore, PI3K complementation experiments indicate that many of the defects observed in IgβKΔR mice can be ascribed to a very specific signaling mechanism. Therefore, it is highly unlikely that the conservative mutations introduced in the Igβ cytoplasmic tail had global effects on BCR structure or function.

In contrast to T-dependent immune responses, TLR7- and 9-dependent responses required BCR ubiquitination and MIIC targeting. This might reflect the importance of endosomal localization for TLR function as proteolytic processing of TLR7 and 9 is necessary for receptor activation (Ewald et al., 2008, 2011; Park et al., 2008; Sepulveda et al., 2009). This dependence on proteolysis links BCR antigen capture to endosomal TLR activation, and ensures discrimination between self and nonself (O’Neill et al., 2009; Mouchess et al., 2011).

Both in vitro and in vivo, increasing signaling through the PI3K–AKT pathway restored normal BCR endocytic trafficking in IgβKΔR splenocytes. These complementation experiments clearly demonstrate a specific signaling pathway critical for BCR endocytic trafficking. However, deletion of Pten in vivo did not rescue TLR9 activation by BCR-targeted ligands nor late B cell development. These observations indicate that Igβ ubiquitination does more than activate PI3K. Whether these functions reflect additional signaling mechanisms or recruitment of other effector complexes to ubiquitinated Igβ is unclear.

In IgβKΔR mice, there was a defect in the immature B cell compartment that persisted into the transitional stage and then largely resolved by the follicular stage. Earlier stages of B cell development were normal. It is at the immature B cell stage that WT BCRs first become competent to enter late endosomes. In contrast, internalized pre-BCR complexes were excluded from the MIIC. Therefore, development was impaired at the stage at which the BCR first becomes competent to enter the MIIC. In pre–B cells, differentiation is directed by the pre-BCR with the single purpose of selecting cells that have productively rearranged the immunoglobulin heavy chain for subsequent light chain recombination (Clark et al., 2014). In contrast, in immature B cells, the TLR-signaling molecules IRAK-4 and MyD88 (Isnardi et al., 2008) shape naive repertoire in humans. These observations suggest that immature B cells might resemble peripheral B cells that depend on the integration of BCR and endosome-restricted signals to determine cell fate.

Much of our knowledge of receptor ubiquitination is derived from in vitro systems (Zhang et al., 2007; Raiborg and Stenmark, 2009). Our in vivo experiments demonstrate that such experiments do not reliably predict in vivo function. In vitro experiments are, by necessity, reductionist and usually rely on soluble antigens available for extended periods of time (Allen et al., 2007). Therefore, it is not surprising that such in vitro experiments do not recapitulate the complexities of in vivo immune responses. Therefore, additional in vivo studies of how ubiquitination contributes to the function of other receptors are needed.

Materials and methods

Mice

All mice were on a C57BL/6 background and were used at 6–12 wk of age. Mice were housed in the Gordon Center for Integrated Sciences barrier animal facility, and experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Chicago. To derive IgβKΔR mice, a targeting vector (Fig. S1 A) was constructed in a C57BL/6 BAC clone in pSP72 (Promega). Mutations were introduced by overlap extension PCR at amino acid codons 157, 185, and 218. A lox-P and FRT flanked neomycin resistance gene was inserted 682 bp downstream of the most 3′ mutation in exon 6 by Red/ET recombineering. Targeting vector was confirmed by restriction digestion and sequencing at each modification step. The construct was then electroporated into C57BL/6 embryonic stem cells, and successfully recombined embryonic stem cells were injected into C57BL/6 blastocysts. After transfer into foster mothers, identified F1 pups were bred to homozygosity. Primers used for screening were IgβKΔR KI-F, 5′-CATTCCCTGCTTCCTGGATA-3′; IgβKΔR-R, 5′-ATGAACAGGGACACCCTCAA-3′; and Neo-R, 5′-CTTCCATCCGAGTACGTGCT-3′, yielding a 1.2-kb band for IgβKΔR and 640-bp band for WT. Sequencing primers were S1, 5′-TTAGGATTCAGCACGTTGGAC-3′; and S2, 5′-CATTCCTGGCCTGGATGCTCTCCTAC-3′. Homozygous IgβKΔR mice were then crossed to the Flpe deleter strain B6.129S4-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(FLP1)Dym/RainJ. WT C57BL/6, CD19Cre, Ptenflx/flx, B6.129S4-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(FLP1)Dym/RainJ, MD4, Tlr7−/−, and B6.SJL-PtprcaPepcb/BoyJ (CD45.1) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. B10;B6-Rag2tm1Fwa II2rgtm1Wjl were purchased from Taconic.

Flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions (106 cells/100 µl) were stained on ice for 1 h with antibodies specific for IgM (Il/41), B220 (RA3-6B2), CD25 (PC61.5), IgD (11-26c), CD93 (AA4.1), CD45.1 (A20), CD45.2 (104), CD23 (B3B4), CD4 (GK1.5), CD8α (53-6.7; all from eBioscience), CD3ε (145-2C11; BD Biosciences), CD43 (S7; BD Biosciences), or CD21 (7G6; BD Biosciences) directly conjugated to FITC, PE, PE-Cy7, Percp-cy5.5, APC, APC-Cy7, or APC-780. Data were collected and analyzed using FlowJo.

Immunizations

Age-matched 6–12-wk-old IgβKΔR and C57BL/6 male mice were injected intraperitoneally with either 50 µg NP49-aminoethylcarboxymethyl-Ficoll (NP-Ficoll), 50 µg alum-precipitated NP29-CGG (Biosearch Technologies) in 300 µl PBS or 2 × 108 SRBC conjugated to NP-OSu. ELISA plates (Immulon 2 HB Flat Bottom MicroTiter; Corning) were coated with 5 µg/ml of NP52-BSA or NP4-BSA (Biosearch Technologies), blocked and incubated with serially diluted serum, washed, and then incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti–mouse IgM or anti–mouse IgG secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Plates were developed using a peroxidase substrate kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and absorbance was measured at 405 nm. For each panel, absorbances at the same dilution were graphed.

For influenza immunizations, age matched 6–12-wk-old IgβKΔR, C57BL/6, and Tlr7−/− mice were injected intramuscularly with 5 µg of inactive A/Switzerland/9715293/2013 virus particles in 50 µl PBS. A boost using the same formulation and route was given 21 d later. Mice were euthanized 21 d after boosting, and their serum and spleens were collected. ELISAs were done using Immulon 2 HB Flat Bottom MicroTiter plates coated with 2 µg/ml of purified hemagglutinin from the A/Switzerland/9715293/2013 virus and horseradish peroxidase anti–mouse IgG2a secondary antibody (Invitrogen). Plates were developed using Super AquaBlue ELISA Substrate (Invitrogen), and absorbance was measured at 405 nm. B cells were purified from the spleens and then RNA was isolated, and quantitative real-time PCR for T-bet was performed as previously described (O’Neill et al., 2009).

Influenza infections and hemagglutination assay

Mice were infected by intranasal instillation with 50 PFU of influenza strain PR8. On day 27, postinfection sera were collected and analyzed for neutralizing antibodies against hemagglutinin (Hirst, 1942) as described previously (Geeraedts et al., 2012).

BCR internalization

B cells were purified from the spleen by negative selection with biotinylated anti-CD11b (M1/70), anti-CD11c (HL3), anti-NK1.1 (PK136), anti–Ter-119, anti-CD3 (452C), anti-CD4 (RM4-5), anti-CD8α (53-6.7), anti–Ly-6G, and Ly-6C (RB6-8C5; all from BD Bioscience), followed by streptavidin magnetic beads (MACS; Miltenyi Biotec). Purified splenic B cells (1 × 105 per sample) were stained with 10 µg/ml FITC-conjugated goat anti–mouse IgG and IgM (H+L) F(ab)2 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) on ice for 15 min. Cells were incubated at 37°C for the indicated times, and internalization assays were performed as described previously (Hou et al., 2006).

Western blotting and immunoprecipitation

Splenic B cells were purified by negative selection as described above. Cells were stimulated with 20 µg/ml F(ab)2 goat anti–mouse IgG and IgM (H+L; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) at 37°C for the indicated times. For Western blotting, cell aliquots were lysed in modified radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing protease inhibitors and PMSF as described previously (Kabak et al., 2002). For ubiquitin immunoblots, cells were lysed as above with the addition of 20 mM N-ethylmaleimide (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 mM 1,10-phenatholine monohydrate (Sigma-Aldrich), and 50 µM PR-619 (LifeSensors). Cellular lysates were precleared with protein G–Sepharose (Pierce), incubated with primary antibodies specific for Igβ (Hm79b; BD Biosciences), and captured with protein G–Sepharose (Pierce). Lysates or immunoprecipitates were resolved on a 4–15% Mini-Protean TGX gel (Bio-Rad) and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Immun-Blot; Bio-Rad). Antibodies with the indicated specificities were used: ERK1/2 (137F5; Cell Signaling), p38 (9212; Cell Signaling), CD19 (3574; Cell Signaling), actin (C4; Millipore), phosphotyrosine (4G10; Millipore), CD79b (Luisiri et al., 1996), antiubiquitin (P4D1; Santa Cruz), and phospho-T202/Y204 ERK1/2 (197G2), pT180/T182 p38 (9244S), pT458 p85 (4228), pS473 Akt (193H12), and Y531 pCD19 (3571; all from Cell Signaling).

Mixed BM chimeras

B10;B6-Rag2tm1Fwa II2rgtm1Wjl (CD45.2) mice were irradiated (550 rad) the day before BM reconstitution. BM cells were harvested, and lineage-negative, Sca-1+, and cKit+ cells from CD45.1 B6.SJL-PtprcaPepcb/BoyJ, CD45.2 WT, or CD45.2 IgβKΔR mice were isolated. Cells were mixed 1:1, and cells were introduced via retroorbital injection. After 8 wk, BM and spleen cells were harvested and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Noncompetitive transfer

B cells from WT×MD4 and IgβKΔR×MD4 mice were labeled with CFSE, which were transferred into B6.SJL-PtprcaPepcb/BoyJ mice and challenged i.v. with HEL-conjugated SRBCs (Lampire Biological Products). After 3 d, spleens were harvested, labeled with anti-CD86, and assayed by flow cytometry. After 6 d, splenic B cells were stained with antibodies to IRF4 and Bcl6 and assayed by flow cytometry (Ochiai et al., 2013).

Confocal microscopy

Confocal microscopy was performed as previously described (O’Neill et al., 2009). Images were collected using a confocal microscope (100× objective; SP5-II-STED-CW; Leica). Antibodies were used to visualize intracellular Syk (C-20; Santa Cruz), H2M (E25A; BD Biosciences), Cathepsin L (CPLH-3G10; Santa Cruz), TLR9 (26C593.2; Abnova), Lamp-1 (1D4B), and Cbl-b (B-5; Santa Cruz). Pre–B cells were incubated with 2.4G2 (LifeSciences) and then biotinylated SL156 (BD PharMingen). After permeabilization, cells were incubated with rabbit antibiotin antibodies (Bethyl Laboratories) and then Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated donkey anti–rabbit antibodies (Invitrogen). Acidic compartments were visualized by incubating samples with 1 µM LysoSensor green DND-1 dye (Molecular Probes) at 37°C for 1 h. Samples were then chilled on ice and imaged. PI3K was inhibited with 5 or 10 µM LY294002 (Selleckchem) for 30 min at 37°C. The CD19 receptor was cross-linked with biotin anti-CD19 (1D3; BD PharMingen) simultaneously with BCR cross-linking after incubating with 2.4G2 (LifeScience). The cells were then incubated for 30 min at 37°C, fixed, and stained. For each experimental time point, images of 30 cells were scored for colocalization using the JACoP plug-in (Manders’ coefficient) of ImageJ (National Institutes of Health). Trilocalization was scored using the BlobProb plug-in (Manders’ coefficient) of ImageJ. A threshold of 40 was set for each channel. Superresolution confocal microscopy images were acquired on a ground state depletion/total internal reflection fluorescence superresolution microscope (63× objective, Leica). WT B cells were stimulated with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated anti-IgG and -IgM (H+L) F(ab)2 antibodies, fixed, and then stained with antibodies to PIP3 (Echelon) and EEA1 (C45B10; Cell Signaling).

T-bet assay and quantitative real-time PCR

Biotinylated ODN 1826 and biotinylated control ODN 2138 were purchased from Invivogen. Purified splenic B cells from WT and IgβKΔR mice were incubated with 20 µg/ml of streptavidin-conjugated F(ab)2 IgG and IgM (H+L), followed by either the biotinylated ODN 1826 or control ODN 2138 (Invivogen). Cells were then incubated for 6 h at 37°C. RNA was isolated and quantitative real-time PCR performed as previously described (O’Neill et al., 2009).

Statistics

Unless otherwise noted, all statistics were done using Student’s t test, using Prism 6 software (GraphPad).

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows the gene-targeting vector used to derive the mutations in the IgβKΔR mouse, confirmed by both PCR genotyping and sequencing. Fig. S1 also shows by immunoprecipitation that these mutations ablated the ability of the Igβ to be ubiquitinated. Fig. S2 shows the cell numbers and surface IgM densities from crossing WT and IgβKΔR mice to Pten−/− mice. Fig. S3 shows the colocalization of PIP3 and BCR in early endosomes at 60 min, along with the absence of colocalization in late endosomes. Fig. S3 also shows the spatial relationship between BCR, PIP3, and EEA1 at 15 min using superresolution confocal microscopy.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sarah Powers for careful reading of this manuscript, Kristen Wroblewski for statistical advice, and Vytas Bindokas and Christine Labno for technical assistance with the superresolution confocal microscopy.

This work was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM088847 and GM101090).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: M. Veselits performed most experiments. A. Tanaka performed experiments described in Fig. S1 (D and E) and Fig. 2 E. BM chimeras were performed by K. Hamel and M. Mandal. B. Manicassamy and M. Kandasamy provided experiments described in Fig. 4 E. Y. Chen and P. Wilson assisted with the experiments described in Fig. 4 (D and E). Noncompetitive transfer was performed by R. Sciammas. S.K. O’Neill helped derive the IgβKΔR mice, and M.R. Clark oversaw the project and prepared the manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

- BCR

- B cell receptor

- BM

- bone marrow

- CGG

- chicken gamma globulin

- GC

- germinal center

- H+L

- heavy chain and light chain

- MIIC

- MHC class II antigen-presenting compartment

- PI3K

- phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PIP3

- phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate

- SRBC

- sheep RBC

- Syk

- spleen tyrosine kinase

- T-bet

- T-box expressed in T cells

References

- Aiba Y., Kameyama M., Yamazaki T., Tedder T.F., and Kurosaki T.. 2008. Regulation of B-cell development by BCAP and CD19 through their binding to phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Blood. 111:1497–1503. 10.1182/blood-2007-08-109769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen C.D., Okada T., and Cyster J.G.. 2007. Germinal-center organization and cellular dynamics. Immunity. 27:190–202. 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum J.S., Wearsch P.A., and Cresswell P.. 2013. Pathways of antigen processing. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 31:443–473. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretscher P., and Cohn M.. 1970. A theory of self-nonself discrimination. Science. 169:1042–1049. 10.1126/science.169.3950.1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter R.H., and Myers R.. 2008. Germinal center structure and function: lessons from CD19. Semin. Immunol. 20:43–48. 10.1016/j.smim.2007.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellino F., and Germain R.N.. 1995. Extensive trafficking of MHC class II-invariant chain complexes in the endocytic pathway and appearance of peptide-loaded class II in multiple compartments. Immunity. 2:73–88. 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90080-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castello A., Gaya M., Tucholski J., Oellerich T., Lu K.H., Tafuri A., Pawson T., Wienands J., Engelke M., and Batista F.D.. 2013. Nck-mediated recruitment of BCAP to the BCR regulates the PI(3)K-Akt pathway in B cells. Nat. Immunol. 14:966–975. 10.1038/ni.2685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi A., Dorward D., and Pierce S.K.. 2008. The B cell receptor governs the subcellular location of Toll-like receptor 9 leading to hyperresponses to DNA-containing antigens. Immunity. 28:799–809. 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi A., Martz R., Dorward D., Waisberg M., and Pierce S.K.. 2011. Endocytosed BCRs sequentially regulate MAPK and Akt signaling pathways from intracellular compartments. Nat. Immunol. 12:1119–1126. 10.1038/ni.2116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., and Jensen P.E.. 2008. The role of B lymphocytes as antigen-presenting cells. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. (Warsz.). 56:77–83. 10.1007/s00005-008-0014-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen S.R., Shupe J., Nickerson K., Kashgarian M., Flavell R.A., and Shlomchik M.J.. 2006. Toll-like receptor 7 and TLR9 dictate autoantibody specificity and have opposing inflammatory and regulatory roles in a murine model of lupus. Immunity. 25:417–428. 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark M.R., Tanaka A., Powers S.E., and Veselits M.. 2011. Receptors, subcellular compartments and the regulation of peripheral B cell responses: the illuminating state of anergy. Mol. Immunol. 48:1281–1286. 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark M.R., Mandal M., Ochiai K., and Singh H.. 2014. Orchestrating B cell lymphopoiesis through interplay of IL-7 receptor and pre-B cell receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14:69–80. 10.1038/nri3570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton E., Bardi G., Bell S.E., Chantry D., Downes C.P., Gray A., Humphries L.A., Rawlings D., Reynolds H., Vigorito E., and Turner M.. 2002. A crucial role for the p110δ subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in B cell development and activation. J. Exp. Med. 196:753–763. 10.1084/jem.20020805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delamarre L., Pack M., Chang H., Mellman I., and Trombetta E.S.. 2005. Differential lysosomal proteolysis in antigen-presenting cells determines antigen fate. Science. 307:1630–1634. 10.1126/science.1108003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel P., Zhou L.-J., Ord D.C., Sato S., Koller B., and Tedder T.F.. 1995. Abnormal B lymphocyte development, activation, and differentiation in mice that lack or overexpress the CD19 signal transduction molecule. Immunity. 3:39–50. 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90157-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewald S.E., Lee B.L., Lau L., Wickliffe K.E., Shi G.P., Chapman H.A., and Barton G.M.. 2008. The ectodomain of Toll-like receptor 9 is cleaved to generate a functional receptor. Nature. 456:658–662. 10.1038/nature07405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewald S.E., Engel A., Lee J., Wang M., Bogyo M., and Barton G.M.. 2011. Nucleic acid recognition by Toll-like receptors is coupled to stepwise processing by cathepsins and asparagine endopeptidase. J. Exp. Med. 208:643–651. 10.1084/jem.20100682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari G., Knight A.M., Watts C., and Pieters J.. 1997. Distinct intracellular compartments involved in invariant chain degradation and antigenic peptide loading of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules. J. Cell Biol. 139:1433–1446. 10.1083/jcb.139.6.1433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruman D.A., Snapper S.B., Yballe C.M., Davidson L., Yu J.Y., Alt F.W., and Cantley L.C.. 1999. Impaired B cell development and proliferation in absence of phosphoinositide 3-kinase p85alpha. Science. 283:393–397. 10.1126/science.283.5400.393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay D., Saunders T., Camper S., and Weigert M.. 1993. Receptor editing: an approach by autoreactive B cells to escape tolerance. J. Exp. Med. 177:999–1008. 10.1084/jem.177.4.999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazumyan A., Reichlin A., and Nussenzweig M.C.. 2006. Igβ tyrosine residues contribute to the control of B cell receptor signaling by regulating receptor internalization. J. Exp. Med. 203:1785–1794. 10.1084/jem.20060221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geeraedts F., ter Veer W., Wilschut J., Huckriede A., and de Haan A.. 2012. Effect of viral membrane fusion activity on antibody induction by influenza H5N1 whole inactivated virus vaccine. Vaccine. 30:6501–6507. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin J.P., Chu R., and Harding C.V.. 1997. Early endosomes and a late endocytic compartment generate different peptide-class II MHC complexes via distinct processing mechanisms. J. Immunol. 158:1523–1532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding C.V., Unanue E.R., Slot J.W., Schwartz A.L., and Geuze H.J.. 1990. Functional and ultrastructural evidence for intracellular formation of major histocompatibility complex class II-peptide complexes during antigen processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 87:5553–5557. 10.1073/pnas.87.14.5553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding C.V., Collins D., and Unanue E.R.. 1992. Processing of liposome-encapsulated antigens targeted to specific subcellular compartments. Res. Immunol. 143:188–191. 10.1016/S0923-2494(92)80163-F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog S., Hug E., Meixlsperger S., Paik J.H., DePinho R.A., Reth M., and Jumaa H.. 2008. SLP-65 regulates immunoglobulin light chain gene recombination through the PI(3)K-PKB-Foxo pathway. Nat. Immunol. 9:623–631. 10.1038/ni.1616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst G.K. 1942. The quantitative determination of Influenza virus and antibodies by means of red cell agglutination. J. Exp. Med. 75:49–64. 10.1084/jem.75.1.49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou B., Saudan P., Ott G., Wheeler M.L., Ji M., Kuzmich L., Lee L.M., Coffman R.L., Bachmann M.F., and DeFranco A.L.. 2011. Selective utilization of Toll-like receptor and MyD88 signaling in B cells for enhancement of the antiviral germinal center response. Immunity. 34:375–384. 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou P., Araujo E., Zhao T., Zhang M., Massenburg D., Veselits M., Doyle C., Dinner A.R., and Clark M.R.. 2006. B cell antigen receptor signaling and internalization are mutually exclusive events. PLoS Biol. 4:e200 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isnardi I., Ng Y.S., Srdanovic I., Motaghedi R., Rudchenko S., von Bernuth H., Zhang S.-Y., Puel A., Jouanguy E., Picard C., et al. . 2008. IRAK-4- and MyD88-dependent pathways are essential for the removal of developing autoreactive B cells in humans. Immunity. 29:746–757. 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jou S.-T., Carpino N., Takahashi Y., Piekorz R., Chao J.-R., Carpino N., Wang D., and Ihle J.N.. 2002. Essential, nonredundant role for the phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110delta in signaling by the B-cell receptor complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:8580–8591. 10.1128/MCB.22.24.8580-8591.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabak S., Skaggs B.J., Gold M.R., Affolter M., West K.L., Foster M.S., Siemasko K., Chan A.C., Aebersold R., and Clark M.R.. 2002. The direct recruitment of BLNK to immunoglobulin alpha couples the B-cell antigen receptor to distal signaling pathways. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:2524–2535. 10.1128/MCB.22.8.2524-2535.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama S., Ishii K.J., Kumar H., Tanimoto T., Coban C., Uematsu S., Kawai T., and Akira S.. 2007. Differential role of TLR- and RLR-signaling in the immune responses to influenza A virus infection and vaccination. J. Immunol. 179:4711–4720. 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosaki T., Shinohara H., and Baba Y.. 2010. B cell signaling and fate decision. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 28:21–55. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leadbetter E.A., Rifkin I.R., Hohlbaum A.M., Beaudette B.C., Shlomchik M.J., and Marshak-Rothstein A.. 2002. Chromatin-IgG complexes activate B cells by dual engagement of IgM and Toll-like receptors. Nature. 416:603–607. 10.1038/416603a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B.L., and Barton G.M.. 2014. Trafficking of endosomal Toll-like receptors. Trends Cell Biol. 24:360–369. 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Siemasko K., Clark M.R., and Song W.. 2002. Cooperative interaction of Ig(alpha) and Ig(beta) of the BCR regulates the kinetics and specificity of antigen targeting. Int. Immunol. 14:1179–1191. 10.1093/intimm/14.10.1179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luisiri P., Lee Y.J., Eisfelder B.J., and Clark M.R.. 1996. Cooperativity and segregation of function within the Ig-alpha/beta heterodimer of the B cell antigen receptor complex. J. Biol. Chem. 271:5158–5163. 10.1074/jbc.271.9.5158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoury B., Mazzeo D., Fugger L., Viner N., Ponsford M., Streeter H., Mazza G., Wraith D.C., and Watts C.. 2002. Destructive processing by asparagine endopeptidase limits presentation of a dominant T cell epitope in MBP. Nat. Immunol. 3:169–174. 10.1038/ni754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrell K.T., Benschop R.J., Gauld S.B., Aviszus K., Decote-Ricardo D., Wysocki L.J., and Cambier J.C.. 2006. Identification of anergic B cells within a wild-type repertoire. Immunity. 25:953–962. 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouchess M.L., Arpaia N., Souza G., Barbalat R., Ewald S.E., Lau L., and Barton G.M.. 2011. Transmembrane mutations in Toll-like receptor 9 bypass the requirement for ectodomain proteolysis and induce fatal inflammation. Immunity. 35:721–732. 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy J.E., Padilla B.E., Hasdemir B., Cottrell G.S., and Bunnett N.W.. 2009. Endosomes: a legitimate platform for the signaling train. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:17615–17622. 10.1073/pnas.0906541106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niiro H., Allam A., Stoddart A., Brodsky F.M., Marshall A.J., and Clark E.A.. 2004. The B lymphocyte adaptor molecule of 32 kilodaltons (Bam32) regulates B cell antigen receptor internalization. J. Immunol. 173:5601–5609. 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill S.K., Veselits M.L., Zhang M., Labno C., Cao Y., Finnegan A., Uccellini M., Alegre M.L., Cambier J.C., and Clark M.R.. 2009. Endocytic sequestration of the B cell antigen receptor and toll-like receptor 9 in anergic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:6262–6267. 10.1073/pnas.0812922106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochiai K., Maienschein-Cline M., Simonetti G., Chen J., Rosenthal R., Brink R., Chong A.S., Klein U., Dinner A.R., Singh H., and Sciammas R.. 2013. Transcriptional regulation of germinal center B and plasma cell fates by dynamical control of IRF4. Immunity. 38:918–929. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omori S.A., and Rickert R.C.. 2007. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling and regulation of the antibody response. Cell Cycle. 6:397–402. 10.4161/cc.6.4.3837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park B., Brinkmann M.M., Spooner E., Lee C.C., Kim Y.M., and Ploegh H.L.. 2008. Proteolytic cleavage in an endolysosomal compartment is required for activation of Toll-like receptor 9. Nat. Immunol. 9:1407–1414. 10.1038/ni.1669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak S.S., and Blum J.S.. 2000. Endocytic recycling is required for the presentation of an exogenous peptide via MHC class II molecules. Traffic. 1:561–569. 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010706.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y., Xu X., Wandinger-Ness A., Dalke D.P., and Pierce S.K.. 1994. Separation of subcellular compartments containing distinct functional forms of MHC class II. J. Cell Biol. 125:595–605. 10.1083/jcb.125.3.595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiborg C., and Stenmark H.. 2009. The ESCRT machinery in endosomal sorting of ubiquitylated membrane proteins. Nature. 458:445–452. 10.1038/nature07961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadani F., Bolland D.J., Garcon F., Emery J.L., Vanhaesebroeck B., Corcoran A.E., and Okkenhaug K.. 2010. The PI3K isoforms p110alpha and p110delta are essential for pre-B cell receptor signaling and B cell development. Sci. Signal. 3:ra60 10.1126/scisignal.2001104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickert R.C., Rajewsky K., and Roes J.. 1995. Impairment of T-cell-dependent B-cell responses and B-1 cell development in CD19-deficient mice. Nature. 376:352–355. 10.1038/376352a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche P.A., and Furuta K.. 2015. The ins and outs of MHC class II-mediated antigen processing and presentation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15:203–216. 10.1038/nri3818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander S., Chu V.T., Yasuda T., Franklin A., Graf R., Calado D.P., Li S., Imami K., Selbach M., Di Virgilio M., et al. . 2015. PI3 Kinase and FOXO1 transcription factor activity differentially control B cells in the germinal center light and dark zones. Immunity. 43:1075–1086. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt O., and Teis D.. 2012. The ESCRT machinery. Curr. Biol. 22:R116–R120. 10.1016/j.cub.2012.01.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepulveda F.E., Maschalidi S., Colisson R., Heslop L., Ghirelli C., Sakka E., Lennon-Duménil A.M., Amigorena S., Cabanie L., and Manoury B.. 2009. Critical role for asparagine endopeptidase in endocytic Toll-like receptor signaling in dendritic cells. Immunity. 31:737–748. 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemasko K., Eisfelder B.J., Stebbins C., Kabak S., Sant A.J., Song W., and Clark M.R.. 1999. Ig alpha and Ig beta are required for efficient trafficking to late endosomes and to enhance antigen presentation. J. Immunol. 162:6518–6525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan L., Sasaki Y., Calado D.P., Zhang B., Paik J.H., DePinho R.A., Kutok J.L., Kearney J.F., Otipoby K.L., and Rajewsky K.. 2009. PI3 kinase signals BCR-dependent mature B cell survival. Cell. 139:573–586. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su X., Lodhi I.J., Saltiel A.R., and Stahl P.D.. 2006. Insulin-stimulated Interaction between insulin receptor substrate 1 and p85alpha and activation of protein kinase B/Akt require Rab5. J. Biol. Chem. 281:27982–27990. 10.1074/jbc.M602873200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiegs S.L., Russell D.M., and Nemazee D.. 1993. Receptor editing in self-reactive bone marrow B cells. J. Exp. Med. 177:1009–1020. 10.1084/jem.177.4.1009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tze L.E., Schram B.R., Lam K.-P., Hogquist K.A., Hippen K.L., Liu J., Shinton S.A., Otipoby K.L., Rodine P.R., Vegoe A.L., et al. . 2005. Basal immunoglobulin signaling actively maintains developmental stage in immature B cells. PLoS Biol. 3:e82 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhaesebroeck B., Guillermet-Guibert J., Graupera M., and Bilanges B.. 2010. The emerging mechanisms of isoform-specific PI3K signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11:329–341. 10.1038/nrm2882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkoczy L., Duong B., Skog P., Aït-Azzouzene D., Puri K., Vela J.L., and Nemazee D.. 2007. Basal B cell receptor-directed phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling turns off RAGs and promotes B cell-positive selection. J. Immunol. 178:6332–6341. 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viglianti G.A., Lau C.M., Hanley T.M., Miko B.A., Shlomchik M.J., and Marshak-Rothstein A.. 2003. Activation of autoreactive B cells by CpG dsDNA. Immunity. 19:837–847. 10.1016/S1074-7613(03)00323-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Brooks S.R., Li X., Anzelon A.N., Rickert R.C., and Carter R.H.. 2002. The physiologic role of CD19 cytoplasmic tyrosines. Immunity. 17:501–514. 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00426-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Veselits M., O’Neill S., Hou P., Reddi A.L., Berlin I., Ikeda M., Nash P.D., Longnecker R., Band H., and Clark M.R.. 2007. Ubiquitinylation of Ig beta dictates the endocytic fate of the B cell antigen receptor. J. Immunol. 179:4435–4443. 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.