Abstract

DNA ‘sliding’ by human repair enzymes is considered to be important for DNA damage detection. Here, we transfected uracil-containing DNA duplexes into human cells and measured the probability that nuclear human uracil DNA glycosylase (hUNG2) excised two uracil lesions spaced 10–80 bp apart in a single encounter without escaping the micro-volume containing the target sites. The two-site transfer probabilities were 100% and 54% at a 10 and 40 bp spacing, but dropped to only 10% at 80 bp. Enzyme trapping experiments suggested that site transfers over 40 bp followed a DNA ‘hopping’ pathway in human cells, indicating that authentic sliding does not occur even over this short distance. The transfer probabilities were much greater than observed in aqueous buffers, but similar to in vitro measurements in the presence of polymer crowding agents. The findings reveal a new role for the crowded nuclear environment in facilitating DNA damage detection.

INTRODUCTION

Many enzymes that act on DNA substrates without the involvement of an energy cofactor have been characterized as proccesive in vitro, where the enzyme can stochastically translocate along a DNA chain before locating a specific target site by sliding or hopping (1–8). Despite the prevalence of these in vitro observations, it is important to keep in mind that enzymes act in a complex cellular environment that differs substantially from test tube conditions. Of note, the cellular environment consists of high inorganic ion and metabolite concentrations (9), lower dielectric properties (10), higher bulk viscosity (11,12), and the presence of high concentrations of macromolecules which consume available volume (‘molecular crowding’) (13–15). These variables within the cellular environment can have a substantial effect on the ability of an enzyme to scan a DNA chain in a processive manner (1,13).

Human uracil DNA glycosylase (hUNG2) is a highly-conserved DNA repair enzyme that excises uracil from U/A and U/G base pairs and initiates the process of uracil base excision repair in all organisms (16–20). Like many human DNA glycosylases (1,2,20–22), hUNG2 has been found to translocate on DNA in vitro, which facilitates the detection and excision of clustered uracils present in a DNA molecule (1,23). The ability of hUNG2 to translocate on DNA in vitro is substantially impacted by both molecular crowding and high ion concentrations that mimic those found in the cellular environment (1,24). In particular, the inert crowding agent PEG8000 (PEG8K) dramatically enhances the average DNA translocation length of hUNG2 as compared to the same measurements in standard buffers that do not contain a crowding agent (24,25). In contrast, the use of a high salt concentration that approximates that in the human cell nucleus severely antagonizes the processivity of the enzyme by promoting enzyme dissociation from DNA (1). The negative effect of salt ions on processivity is substantially counteracted in the presence of crowding because the large crowding molecules form a cage around the translocating enzyme and DNA, hindering the escape of the enzyme into bulk solution (24,26). The significant in vitro effects of crowding and monovalent ions on translocation by hUNG2 raises the question of whether enzyme translocation occurs in the nucleus of human cells and if it is functionally important for DNA repair. In this study, we develop a high-resolution site translocation assay to elucidate the translocation behavior of hUNG2 in human cells. To our knowledge, these are the first measurements that directly assess the nanoscale proccesive action of an enzyme in human cells. This approach reveals a major contribution of nuclear macromolecule crowding to productive DNA translocation and several other fundamental aspects of the damage search within human cells by this enzyme.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA oligonucleotides

DNA oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) and were purified by gel electrophoresis before use (see Supplementary Information). The sequences of the DNA molecules used in this work are listed in the Supplementary Information.

Cell lines

Hap1wt and Hap1ΔUNG human cell lines were purchased from Horizon Discovery. The Hap1ΔUNG cell line contains a deletion that prevents expression of both the nuclear and mitochondrial forms of hUNG. Hap1ihUNG2 was prepared in house by lentiviral transduction of Hap1ΔUNG. The full-length hUNG2 gene was transferred into pCW57.1 (AddGene) destination vector via standard Gateway cloning (Gateway Clonase ii Kit, Invitrogen) from pENTR4 vector (AddGene). pCW57.1 contains the puromycin resistance gene and a tetracycline inducible CMV promoter. The resulting plasmid pCW57.1(hUNG2) was sequenced, to confirm a 100% sequence match to that of hUNG2 nuclear isoform (CCDS 9124.1). This plasmid was transfected into the HEK293 producer cell line along with the packaging plasmids pRRE, PRSV-rev and pMD2.g (AddGene) using lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent and Opti-MEM transfection medium. The transfected cells were cultured in RPMI-1640, 10% FBS, 1% Pen-Strep medium (R-10) for 72 h. The production and purification of lentiviral particles is described in detail in the Supplemental Information.

Cell culture

In experiments involving Hap1wt and Hap1ΔUNG the culture medium was DMEM-10. For Hap1ihUNG2, DMEM-10 was supplemented with 1 μg/ml puromycin (DMEM-10-P; non-inducing conditions) and 1 μg/ml doxycycline (DMEM-10-P-D; inducing conditions).

Transfection with oligonucleotides

Hap1ΔUNG, Hap1ihUNG2 or Hap1wt cells were thawed in 37°C water bath for 2 min. and washed with either DMEM-10 or DMEM-10-P two times to remove all DMSO. Cells were plated in T-75 flasks and incubated under standard conditions (see above) for at least 36 h. The cells were released by 0.5% Tripsin-EDTA, washed twice with appropriate medium, plated in T-75 flasks at a density of 5 × 106 cells/flask and allowed to adhere for 12–16 h after which the cells were 50 to 90% confluent. The best transfection results were obtained when the cells were ≈ 70% confluent. The transfecting oligonucleotide was dissolved in 920 μl of Opti-MEM media in a 15 ml falcon tube to give a concentration of 2.5 μM. To a second 15 ml falcon tube 55 μl of Opti-MEM media and 25 μl of oligofectamine was added. The oligofectamine solution was mixed gently and incubated for 5 min at room temperature before transferring into the tube containing the probe DNA. After mixing, the resulting solution was incubated at room temperature for another 25 min. The T-75 flask to be transected was then taken out of incubator and the media was aspirated and replaced with 4 ml of Opti-MEM. One-milliliter of the transfection medium was added to the T-75 flask and mixed by gently rocking the flask several times. The transfection cultures were incubated for 4 h, after which the transfection medium was removed and replaced with appropriate media (DMEM-10, DMEM-10-P or DMEM-10-P-D) and incubated for another 6 h to allow hUNG2 expression.

Translocation assays

At six-hours post-transfection the cells were released from the flask with 0.5% Trypsin-EDTA, washed two times and resuspended in 5 ml of appropriate media (DMEM-10, DMEM-10-P or DMEM-10-P-D). Turbo DNAse was added to each sample to a final concentration of two units/ml and incubated for 15 min at room temperature to digest any DNA that might be bound outside the cell membrane. The cells were then washed two times with PBS and lysed using 2.5 ml of denaturing lyses buffer (DLB) per sample (100 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.5, 5 mM EDTA, 200 mM NaCl, 0.2% SDS, 0.2 mg/ml of proteinase-K). Then 2.5 ml of PBS was added and vortexed. The 5 ml sample was sonicated for 15–20 min. in a tabletop sonicator (Branson 1210) to shear the genomic DNA and decrease the solution viscosity. Five-milliliters of phenol–chloroform solution (Sigma) was added to each sample, followed by vortexing and centrifugation at 2800 g (Sorval Legend RT) at room temperature for 30 min. The upper aqueous phase (4.5 ml) containing the DNA was carefully removed with a pipette so as not to carry over large amount of genomic DNA and denatured proteins. The aqueous phase was brought to a volume of 5 ml using PBS and extracted two more times with 5 ml of phenol–chloroform. The final extract was buffer exchanged ≈10 000-fold into buffer LS (20 mM HEPES·K, pH 7.4, 3 mM K·EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.002% Brij-35) using an Amicon Ultra 4 ml (Milipore) spin concentrator (10000 MWCO). The final extract volumes after concentration were in the range 50–100 μl. The concentration of fluorescent DNA in each sample was adjusted by addition of buffer LS so as to match that of the most dilute sample.

Gel electrophoresis, image collection and data analysis

DNA fragments were separated using PAGE (8 M urea, 1× TBE, 14% acrylamide) and the gels (15 cm × 15 cm × 0.3 mm) were pre-run for at least 15 min at 25 W power. The sample DNAs were split into three equal portions for analysis. The first sample serves to measure the level of intracellular uracil excision and abasic site cleavage. To this sample, three volumes of FL solution was added (98% formamide, 10 mM Na·EDTA) and the sample was kept at room temperature and loaded directly on the gel without heating or adding base. The second sample is used to determine if there are any residual abasic site repair intermediates present from intracellular action of hUNG2. This sample is treated with 1/5 volume of 1 M NaOH and incubated at 70°C for 15 min followed by the addition of three volumes of FL solution. The third sample is used to determine if any U/A base pairs have been converted to T/A base pairs. This question is addressed by treating the sample with 10 nM UNG (catalytic domain of hUNG2) at 37°C for 1 h, quenching with 1/5 volume of 1 M NaOH and incubating at 70°C for 15 min to cleave abasic sites. The observation of bands A and C and no other bands after this treatment establishes that no T/A base pairs were present. Ten to twenty-micoliters of each sample was loaded onto the gel along with markers generated by partial in vitro digestion of the substrate DNA with UNG. The gels were run for 45, 50 and 65 min for the U10/T10, U40 and U80 DNA probes respectively. The samples were imaged at a voltage that avoided overexposure (typically 775–850 V) on a Typhoon 9500 imager. The raw gel images were quantified via QuantityOne software with an automatic background subtraction. Raw Ptrans values (uncorrected for fraction reaction) were calculated using Equation (1), where Ptrans is the observed probability of translocating between the two uracil sites on the probe DNA at a given extent reaction.

|

(1) |

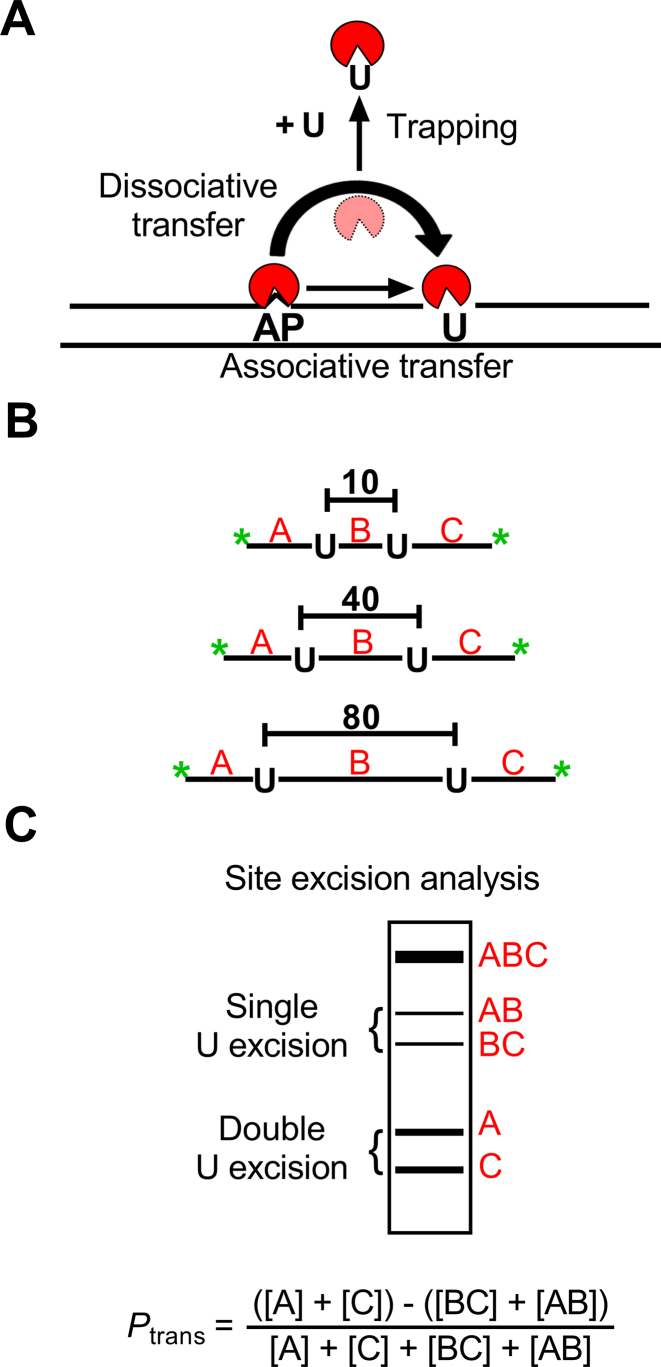

In Equation (1), [A] and [C] are the band intensities of the two-site excision products and [AB] and [BC] are derived from the single site excision products (Figure 1B). In the cellular Ptrans measurements, the reaction extents were kept in a narrow range of 17–31%, to minimize the need for large corrections that take into account possible second hit events (10). In the Supplemental Information, we describe an analytical approach that calculates corrections to the raw Ptrans to take into account small differences in the extent of reaction between the measurements.

Figure 1.

Intracellular DNA translocation assay by hUNG2. (A) Intramolecular transfer of hUNG2 between uracil sites can follow an associative or dissociative pathway. The graphic depicts the transfer of hUNG2 between an AP site generated by uracil excision and a second nearby uracil site. The associatve and dissociative transfer pathways that comprise Ptrans can be deconvoluted by including a uracil (U) trap in the reaction. Associative transfers occur in a DNA bound conformation, where the enzyme active site is protected from the uracil trap. Dissociative transfers occur by micro-dissociations that expose the active site to the uracil trap (34). When sufficently high concentrations of uracil trap are included (>10 mM) (1) dissociative transfers (Pdiss) can be eliminated and the remaining transfers occur by the associative pathway (Pass), where the total transfer probability is the sum of both transfer pathways (Ptrans = Pass + Pdiss). (B) Translocation measurements were made using uracil-containing substrates with two uracil sites spaced 10, 40 or 80 bp apart (U10, U40, U80). Green asterisks denote end-labeling with FAM fluorophores. (C) Distributive uracil excision by hUNG2 yields the single-site excision fragments AB and BC and intramolecular site transfer between the sites yields fragments A and C. As depicted, the fragments are separated by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Greater intensities of the A and C two-site excision bands relative to the AB and BC bands is indicative of intramolecular translocation as defined by the displayed equation (Ptrans).

Enzymatic activity assay

To determine the activity of hUNG2 in cell extracts, we used a previously described continuous fluorescence assay (27). Briefly, 2 × 106 cells of Hap1ΔhUNG, Hap1ihUNG2 (induced or uninduced) or Hap1wt were lysed on ice for 30 min in 200 μl of CellLytic native lysis buffer (Sigma) and the cell debris were removed via centrifugation at 21 000 g in pre-chilled 5424R centrifuge (Eppendorf) for 20 min at 4°C. The cell extracts were removed and kept on ice. The total protein concentration in each extract was measured using the Bradford assay (Biorad) with BSA (NEB) as the standard. The concentrations of the extracts were adjusted to 0.5 μg/μl with CellLytic buffer. Continuous fluorescence kinetic measurements were made using a Fluoromax-3 spectrofluorometer (Horiba) with excitation and emission wavelengths set to 492 and 518 nm (FAM), respectively. The excitation and emission slit widths were 1 and 4 mm, respectively. Reactions contained 50 nM hairpin substrate (HP18) in buffer LS and 10 μg of each cell extract. The time courses were followed over 500 s with 2 s signal integration time, 10 s measurement intervals with excitation shutter closing between measurements to avoid photo bleaching. To confirm that the enzymatic activity was from hUNG2, we established that the activity was inhibited by the addition of 2 μM of uracil DNA glycosylase inhibitor protein (UGI). Reference reactions were performed under the same conditions using purified full-length hUNG2 from a bacterial expression system. The activities were determined by linear regression fitting to the first 30% of the time courses. The time integrated concentration of hUNG2 over the 6 h induction in Hap1ihUNG2 cells was estimated as described in Supplemental Information.

Flow cytometry

The transfection efficiency of Hap1 cells was determined using the U10 probe DNA using a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur flow cytometer. Prior to analysis, the cells were treated with Turbo DNase (2 units/ml) for 15 min to remove any DNA bound to the surface of the cells and washed with PBS at least three times before counting in the flow cytometer. The FAM fluorescence gating was set such that 99.9% of the untransfected cells would be reported as negative. Typical sample size was 106 cells at a concentration of 106/ml. Two to five × 104 cells were measured in each flow experiment to obtain good population statistics.

Statistics

All errors in the Ptrans measurements are based on triplicate biological measurements. Average values with standard errors are plotted in all figures. The site spacing dependence of Ptrans was fit to a Gaussian distribution (Equation 2) to estimate

|

(2) |

the average translocation distance (i.e. the distance where 67% of all molecules of hUNG2 successfully transfer from site A to site B). In Equation (2), A is the maximal value of Ptrans, d is the base pair spacing between uracils on the probe DNA, δ is the mean standard deviation and μ is the origin point. Since we consider translocation to be bi-directional and symmetric (5′ to 3′ and 3′ to 5′ transfer rates are equivalent), then μ = 0. The mean translocation length (λ) is then calculated as:

|

(3) |

The time dependence of hUNG2 induction was done in biological triplicates at 2, 4, 6 and 8 h post doxycycline induction. The time averaged activity traces were plotted as the function of time.

RESULTS

Enzyme translocation on DNA chains can occur by two types of transient diffusive states (28). These states involve complexes where the enzyme is continuously associated with the DNA, as well as transiently dissociated states where the enzyme is poised to rebind with high probability (Figure 1) (4,26,29–31). We have referred to these states as associative and dissociative, but the literature has used the terms sliding and hopping, respectively (3,32,33). The translocation of hUNG2 along DNA can be probed using substrates that contain two uracil sites with known spacing, and is quantified with a parameter called the site transfer probability (Ptrans) (34,35). The transfer probability measures the fraction of enzyme molecules that excise one uracil site and then successfully translocate and excise the other uracil in the same DNA molecule without getting lost to bulk solution. Experimentally, Ptrans can be determined by measuring the relative amounts of the expected DNA fragments produced from double site versus single site excision events under initial rate single encounter conditions ([DNA] >> [E], see below) (34). A useful variation of the method employs a small molecule trap (uracil) that inhibits enzyme molecules attempting to transfer by the dissociative pathway (Figure 1) (34). Accordingly, any transfers that persist at high trap concentration must follow the associative pathway because the active site remains sterically inaccessible to the trap during associative transfers (34).

Cellular translocation assay

Our approach involves transfecting human cells (Hap1) with fluorophore-labeled DNA duplexes containing two uracils spaced 10, 40 or 80 bp apart (U10, U40, U80, Figure 1B). These molecules must be recovered from cell extracts at various times after transfection to evaluate the fraction of the DNA molecules where both uracil sites were cleaved by hUNG2. When hUNG2 lands on a DNA molecule and excises one of the uracil sites, it may diffuse away from that DNA to bulk solution or translocate to the second uracil site and excise the uracil. Thus, translocation is indicated by higher levels of two-site cleavage events as compared to single-site cleavage events under initial rate single-encounter conditions ([DNA] >> [E]free). As indicated in Figure 1C, the single-site cleavage events generate bands AB and BC (after sample processing and electrophoresis), while the two-site cleavage events produce bands A and C. The algebraic definition of the DNA translocation efficiency (Ptrans) is based on the fragment band intensities as shown in Figure 1C. Qualitatively, intramolecular two-site excision results in greater amounts of bands A and C relative to AB and BC, which can be discerned by visual inspection of gels. Although this is a conceptually simple extension of our in vitro assay, there are numerous potential complications that could adversely influence the cell based measurements and many controls were performed to validate the observed results.

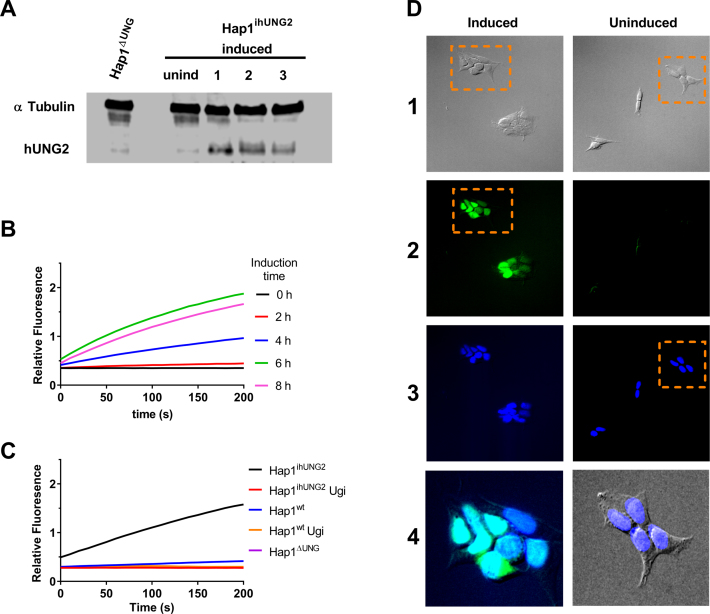

Characterization of uracil DNA glycosylase activity in Hap1 cells

A key tool in our strategy is the use of an inducible hUNG2 cell line (Hap1ihUNG2) where expression of hUNG2 is under the control of a doxycycline inducible CMV promoter (Supplemental Information). This inducible cell line was constructed from a hUNG genomic knockout (Hap1ΔUNG) that lacks both the mitochondrial and nuclear forms of the enzyme (hUNG1 and hUNG2). We used Western blotting to confirm that Hap1ΔUNG showed no detectable expression of either hUNG isoform and that hUNG2 expression in Hap1ihUNG2 cells was under strict control (Figure 2A). We also measured the time course for induction of hUNG2 activity in Hap1ihUNG2 cells by isolating cell extracts under native conditions at various times after doxycycline exposure and determined the enzyme activity with an in vitro continuous fluorescence assay (Figure 2B) (36). Based on the time course for attaining maximal activity, an induction time of 6 hours gave rise to 10 to 15-fold greater hUNG2 expression than measured in the Hap1wt cells. We established that all of the U/A glycosylase activity present in these cell extracts was inhibited by the highly specific phage derived UNG inhibitor, UGI (37) (Figure 2C). This result eliminated the possibility that any of the three human DNA glycosylases with activity against T/G and U/G base pairs (TDG, SMUG, MBD4) was contributing to the observed excision of uracil from U/A base pairs in our assay (27). Immunofluorescence staining confirmed that all of the expressed hUNG2 was localized to the nucleus in Hap1ihUNG2 cells (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Characterization of the Hap1ΔUNG and inducible Hap1ihUNG2 cell lines. (A) Western blot analyses of hUNG2 expression in the Hap1ΔUNG and the inducible Hap1ihUNG2 cell line at 16 h post induction using 1 μg/ml of doxycycline (see Supplemental Methods). The three numbered lanes are extracts obtained from three distinct clonally-expanded Hap1ihUNG2 cell lines, generated via transduction of Hap1ΔUNG with different concentrations of hUNG2 gene carrier lentivirus; all of the experiments in this paper were performed with cell line 2. (B) The time course for induction of hUNG2 activity in the inducible strain Hap1ihUNG2 was determined from cell extracts obtained at various times after induction. A robust continuous fluorescence activity assay was employed (see methods). Induction with 1 μg/ml of doxycycline resulted in robust hUNG2 expression that leveled off at about 6 h post-induction. All traces are the average of triplicate biological measurements. (C) Uracil excision activity in cell extracts arises solely from hUNG2. Extracts were obtained from the Hap1ihUNG2 cell line at 6 h post-induction and also the Hap1wt and Hap1ΔUNG cell lines. Ten micrograms of total cell protein was used in each assay. The continuous fluorescence assay employs the HP18 DNA substrate (see Supplemental Information). All traces are the average of triplicate measurements. The observed activity was completely inhibited by the inclusion of 2 μM uracil DNA glycosylase inhibitor protein (UGI), which is highly specific for hUNG2. (D) The nuclear compartment comprises at least 50% of the volume of Hap1 cells and overexpressed hUNG2 is localized to the nucleus. The Hap1ihUNG2 cell line was induced with 1 μg/ml doxycycline for 6 h prior to fixing and specific staining for hUNG2 (see Supplemental Methods). Non-induced Hap1ihUNG2 cells were stained using the same procedure. The vertical numbered panels are (1) transmitted light images, (2) hUNG2 immunofluorescence staining with Alexa 488 detection, (3) DAPI staining of nucleus, and (4) zoomed merges of the indicated panel regions. Images in each panel were taken on Olympus fluorescence microscope under 20x magnification. The zoomed regions are (i) an overlay of the indicated DIC and DAPI stained images, where the DAPI channel brightness was linearly enhanced for easier visual assessment, and (ii) overlay of the DAPI and Alexa 488 channels. The brightness of both channels was linearly adjusted to demonstrate nuclear colocalization of both fluorescence signals.

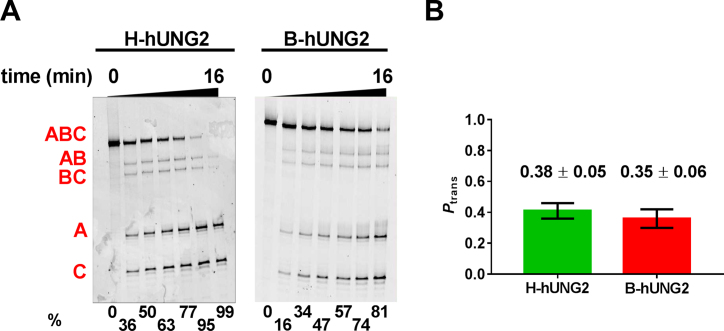

hUNG2 expressed in human cells has identical translocation activity as the bacterial expressed enzyme

hUNG2 is known to undergo post-translational modifications in its disordered N-terminal domain which could impact its ability to translocate on DNA in cells as compared to in vitro measurements with the unmodified enzyme purified from a bacterial expression system (B-hUNG2) (38–40). To evaluate if hUNG2 present in Hap1ihUNG2 cell extracts (H-hUNG2) had the same in vitro translocation activity as the bacterially expressed enzyme, we reacted both enzymes with the U40 substrate in the presence of PEG8K and resolved the excision bands on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel (Figure 3A). The in vitro translocation efficiencies (Ptrans) of the two enzymes were indistinguishable, establishing that any posttranslational modifications that might be present do not affect the translocation behavior (Figure 3B). We also show below that the translocation behavior of the endogenous hUNG2 expressed in Hap1wt cells is indistinguishable from the overexpressed enzyme.

Figure 3.

hUNG2 expressed in Hap1ihUNG2 cells has the same in vitro translocation activity as the enzyme overexpressed and purified from bacteria. (A) Time-courses for in vitro excision of uracils from U40 using extracts from Hap1ihUNG2 cells (H-hUNG2) and purified hUNG2 obtained from a bacterial expression system (B-hUNG2). The excision products of quenched reactions were treated with NaOH and heat, resolved on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel and then imaged. The reaction extents (in percent) for each time point are shown at the bottom of each gel. (B) Ptrans measurements with the U40 substrate for H-hUNG2 and B-hUNG2 in the presence of 20% PEG8K and 150 mM K+ are indistinguishable.

Characterization of the uracil excision products in Hap1 cell lines

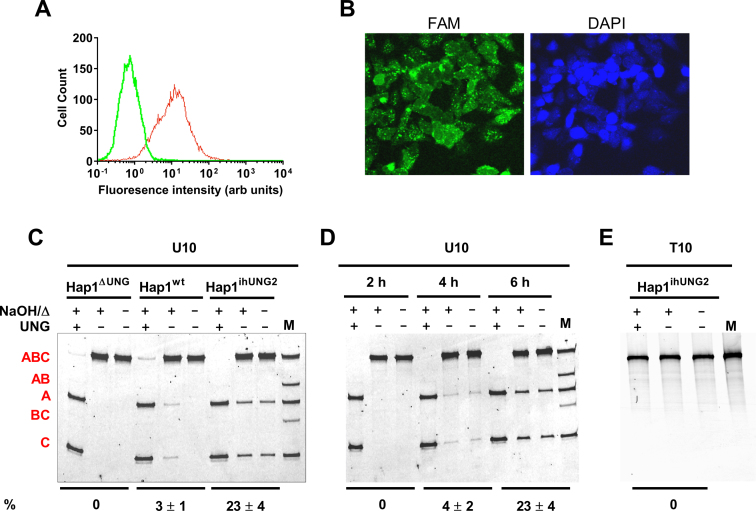

We used DNA probe U10 to optimize the transfection conditions with the Hap1 parent cell line (Hap1wt) using flow cytometry. We routinely observed a transfection efficiency of 70 ± 10% using a four-hour transfection time in the presence of oligofectamine (Figure 4A). Based on fluorescence quantification of the DNA recovered from extracts of transfected cells, the average number of DNA molecules per cell was ∼20 000. Assuming a cell volume of ∼2000 μm3 (see Supplemental Methods), this corresponded to an average concentration of about 200 nM U10 per cell. Measurement of Ptrans does not require transfection of all cells, but high transfection efficiency increases the signal-to-noise. Similar transfection efficiencies were observed with Hap1ihUNG2 and Hap1ΔUNG cells.

Figure 4.

Validation of site transfer assay in human cells. (A) Transfection efficiency of substrate U10 was determined by flow cytometry. The efficiency (fluorescent cells/ total cells) was 70 ± 10% and the other substrates were similar. (B) Cellular localization of transfected substrate U10 in Hap1ihUNG2 cells. Confocal microscopy was used to image Hap1ihUNG2 cells 6 h post-induction. The right image is DAPI-stain and the left image detects the fluorescein-labeled U10 probe. The green fluoresence of the U10 probe is diffuse throughout the entire cell, indicating that the DNA is in equilibrium between the cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments, where the DNA becomes accessible to hUNG2. The images were collected using 40X magnification. (C) Excision of uracils from the transfected substrate U10 requires hUNG activity. U10 DNA was isolated from the hUNG1/2 knock-out (Hap1ΔUNG), wild-type (Hap1wt), or inducible cell line (Hap1ihUNG2) at 10 h post-transfection and treated in three ways before analysis on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel: NaOH and heat (NaOH/Δ) to cleave any abasic sites that were generated inside cells; in vitro UNG digestion followed by NaOH and heat (Δ) to detect any unreacted uracil sites; no base, heat or hUNG treatment to detect cleaved abasic sites generated in cells after uracil excision. The lane marked M is a partial in vitro hUNG digestion of U10 (followed by NaOH/Δ) to generate size markers for fragments AB, BC, A and C. The reaction extents (in percent) for each sample are shown at the bottom of the gel. (D) Time-course for cellular excision of uracils from U10 over the time course for induction of Hap1ihUNG2 cells. The Ptrans values are identical at reaction extents between 3 and 25% (4 h and 6 h), indicating that these fragments arise from single encounters with hUNG2 rather than separate iterative encounters. The reaction extents (in percent) for each time point are shown at the bottom of the gel. (E) In the absence of U/A base pairs, transfected DNA shows no excision fragments in fully induced Hap1ihUNG2 cells. The T10 probe used in this transfection is identical to U10 except that the two uracils are replaced with thymidine. All measurements were performed as biological triplicates. A further stability test of T10 that includes Hap1ΔUNG and Hap1wt cells is shown in Supplemental Figure S3.

In further control experiments, we established that at least 80% of the full-length transfected duplex DNA with dual 5′ and 3′ Fam end-labels was preserved inside Hap1 cells after 6 h (Supplemental Figure S1B and C). Even greater stability was observed in vitro using cell extracts obtained from Hap1ihUNG2 cells (Supplemental Figure S1D-E). Importantly, there was no change in the end-labeling ratio of the full-length DNA recovered from cells, which is an essential requirement for meaningful Ptrans measurements (see below). Thus, any loss in full-length transfected DNA is invisible to our Ptrans measurements. This finding indicates that either the fluorophores are completely removed from a small fraction of the DNA, making these DNAs invisible to detection, or that degradation spreads the fluorophore signal over many products that only contribute to background. Finally, control experiments also established that the DNA duplexes used in this study remain in their duplex form when extracted from Hap1ihUNG2 cells at six hours post-transfection (Supplemental Figure S2). The high duplex stability may arise from the protective effects of the duplex structure, the presence of two protective Fam end-labels, or the nuclease expression profile of Hap1 cells.

To investigate the cellular localization of transfected U10 DNA, we fixed transfected Hap1ihUNG2 cells and obtained confocal microscopy images under induced conditions (Figure 4B). These images show that the DNA is diffuse around the entire cell with some bright puncta that are localized to the nuclear periphery. Thus, the DNA equilibrates between the cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments, where the DNA becomes accessible to nuclear hUNG2. Thus, the data establish that the much of the DNA and virtually all of the hUNG2 are in the nuclear compartment. Further, at least 50% of the cell volume of Hap1 cells is nuclear, which means most of the DNA is accessible by hUNG2 at any instant. If any small amount of reaction happens to be occurring in the cytoplasmic compartment, it is weight-averaged into the observed measurements.

The absence of hUNG2 activity in Hap1ΔUNG cells was confirmed by transfecting probe U10 into these cells and isolating cell extracts under denaturing conditions at 6 h post-transfection. Analysis of the extracted DNA on an 8 M urea denaturing polyacrylamide gel revealed a single band with the same molecular weight as the input DNA (Figure 4C). When the same DNA sample was treated with base and heated prior to gel analysis, the same single band was observed indicating that no base-labile abasic sites were present. When the extracted DNA was treated with UNG in vitro, followed by base and heat, the entire substrate DNA was converted into two smaller fragments that corresponded to excision of the two uracil sites. This important result established that 100% of the recovered uracils were retained over the entire six-hour experiment in Hap1ΔUNG cells. Thus, no other DNA repair activity that can act on U/A base pairs is present in the cells.

We then investigated the time course for uracil excision from substrate U10 in transfected Hap1ihUNG2 cells (Figure 4D). Extraction of the U10 DNA at two, four and six hours post-induction showed a time-dependent increase in amounts of two small DNA fragments that corresponded to the sizes of the A and C two-site excision products. In contrast, no detectable amounts of the AB and BC single-site excision products were observed. This result suggested that the translocation efficiency over this short 10 bp spacing was essentially 100%. The observation of these bands in the absence of treating the extracted sample with base and heat is consistent with intracellular uracil excision by hUNG2 followed by phosphodiester cleavage by APE1 abasic site endonuclease (Figure 4D), which is the subsequent enzyme in the uracil base excision repair pathway. Upon treatment of the extracted DNA with base and heat, the A and C band intensities increased by about 20%, indicating that some of the DNA migrating with the substrate contained abasic sites that had not yet reacted with APE1 in cells. Upon in vitro treatment with UNG, base and heat, the entire input DNA was cleaved to the A and C bands establishing that none of the substrate had undergone complete repair to convert the U/A pairs to T/A. Based on these results, APE1 efficiently reacts with the abasic sites generated by induced hUNG2, but the subsequent repair enzymes in the pathway are not effectively locating the nicked abasic sites (i.e. polβ or DNA ligase III or both). This result substantially simplifies the analysis because corrections that consider fully and partially repaired sites are unnecessary, which reduces uncertainty in Ptrans determination. Finally, we established that the excision bands were only observed when the substrate contained U/A base pairs because transfection of Hap1ihUNG2 cells with an identical DNA construct containing two T/A pairs (T10) produced no such products (Figure 4E, Supplemental Figure S3).

Establishing initial-rate single-encounter conditions in cells

An essential requirement for this assay is that each DNA molecule must be acted upon by a single enzyme molecule (single-hit conditions) (35). Otherwise, the results do not reflect intramolecular transfer of a single enzyme, but instead, reflect a second-hit event by another hUNG2 molecule after the first uracil was excised. In vitro, single-hit conditions can be assured by using low ratios of enzyme to DNA, and by following the reaction under initial rate conditions (<25% reaction) (35). In the context of cells, we used several experimental criteria to validate that single-hit conditions prevailed with U10 (see also Discussion). First, identical two-site excision frequencies were observed with substrate U10 in Hap1ihUNG2 cells when the reactions were stopped at four and six hours (corresponding to percent reactions of 3% and 23%; Ptrans = 1) (Figure 4D). This result establishes that the Ptrans measurements are independent of both hUNG2 concentration and extent of reaction in this timeframe. In addition, the same two-site excision frequency was observed with Hap1wt where the hUNG2 expression is 10- to 15-fold less than Hap1ihUNG2 and the reaction extent was also about 3% (Ptrans = 1, Figure 4C). The identical behavior of the overexpressed and endogenous enzyme establishes that the results are not biased by overexpression. The final evidence supporting single-encounter conditions is provided by the substrates with larger site spacings, where decreasing values for Ptrans were observed (see below). If multi-hit kinetics were responsible for the large observed Ptrans value with U10, the substrates with longer site spacings would also show the same high value because high concentrations of the free enzyme have the same probability of reacting with uracil regardless of the site spacing.

Site-spacing dependence of intracellular DNA translocation

After validating the intracellular translocation assay using U10, we constructed substrates with uracils spaced 40 and 80 bp apart and tested the ability of hUNG2 to translocate over these site spacings in cells. The transfections were allowed to proceed for 4 h, at which time the expression of hUNG2 was induced by the addition of doxycycline. The assays were terminated at 6 h post-induction and the DNA was extracted (Figure 5A). The DNA extracts were analyzed on a 14% denaturing polyacrylamide gel containing 8 M urea, with or without UNG or base/heat treatment as described above. In the case of U10, only two-site cleavage products were observed, indicating that Ptrans = 1 for this spacing (Figure 5A). In contrast, the U40 substrate showed both single and two-site excision bands, indicating that some hUNG2 molecules fell off the DNA in the process of translocating to the second site 40 bp away (Ptrans = 0.54 ± 0.05, Figure 5A). Finally, for the 80 bp spacing the single and two-site excision fragments showed nearly identical intensities, indicating that very few hUNG2 molecules successfully translocated over this distance (Ptrans ≈ 0.10 ± 0.02) (Figure 5A). For all three substrates, all of the DNA that migrated at the position of substrate DNA contained two uracil sites based on susceptibility to in vitro excision by hUNG (Figure 5A). Thus, as observed with U10, none of the uracils were fully repaired during the 6 h incubation.

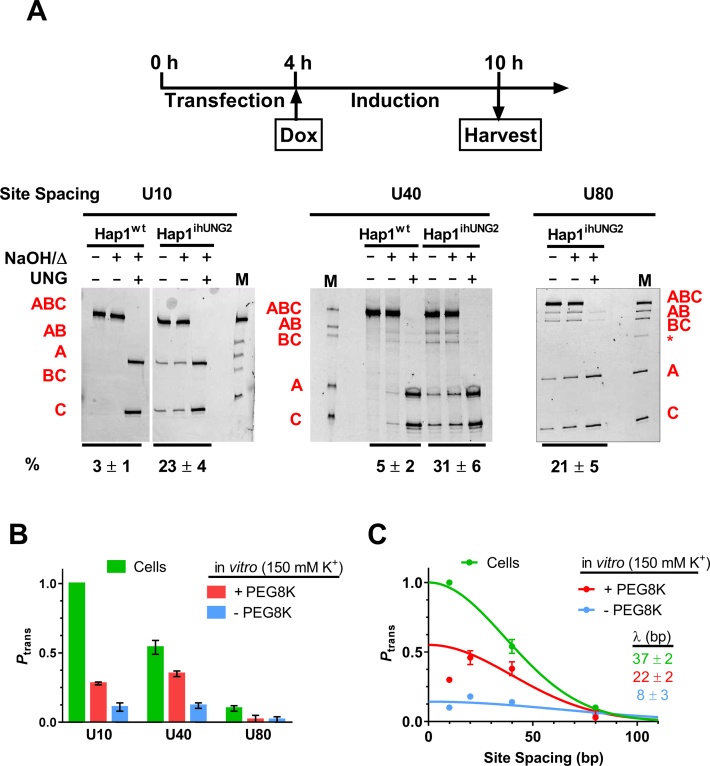

Figure 5.

Dependence of the translocation efficiency (Ptrans) on site spacing. (A) The uracil-containing probe DNAs are transfected into Hap1 cells for 4 h and hUNG2 induction was initiated by addition of doxycycline (Dox). At 6 h post-induction, cells were harvested and assessed for uracil excision (see Materials and Methods). The electrophoretically resolved band fragments from the site transfer measurements with substrates U10, U40 and U80 are shown. Each experiment was performed at least three times. The in vitro treatments that were performed with each DNA prior to electrophoresis are described in the legend to Figure 3C. The reaction extents (in percent) for each sample are shown at the bottom of the gel. The asterisk in the marker lane for U80 is a low level (<2%) of single-strand contaminant that was carried over from the native gel purification of the U80 probe. The Ptrans for the U40 substrate obtained from measurments in Hap1wt cells is 0.5 ± 0.2, which overlaps the value obtained with the inducible line. This measurement has a large error due to the weak band intensities arising from the low percentage reaction. (B) Comparison of cellular Ptrans measurements with previous in vitro measurements performed in the presence and absence of the polymer crowding agent PEG8K (25). The in vitro measurements used buffers containing 150 mM K+. All experiments were performed at least three times, and the standard errors of measurements are indicated. The values for the cellular measurements that are shown were corrected for small differences in extent of reaction for the three substrates (see Supplementary Information). (C) Determination of the mean translocation distance (λ) of hUNG2 in human cells and in vitro. The solid lines are best fits to a single Gaussian distribution (Equation 2) and the mean translocation length was determined using Equation (3). The fitted curve for the in vitro data set in the presence of PEG8K excluded the data point for the 10 bp spacing because it showed a negative deviation from the theoretical curve (see text).

Comparison of in vitro and intracellular translocation efficiencies

The intracellular translocation measurements can be compared with previous in vitro measurements in the absence and presence of 20% PEG8K, a model for macromolecular crowding in the cell (1,24). Although hUNG2 shows little translocation in vitro using a salt concentration that approximates the intracellular milieu (150 mM K+), its ability to translocate is substantially enhanced in the presence of PEG8K (compare red and blue bars in Figure 5B). However, the translocation distances observed in cells are even greater than the in vitro crowding condition, indicating that the properties of the intracellular milieu are highly conducive to translocation (Figure 5B). We note that the site spacing dependence of Ptrans using the in vitro crowding condition tracks with the intracellular measurements at site spacings greater than 10 bp. However, for the in vitro measurement at the short 10 bp spacing, a negative deviation in Ptrans was observed (Figure 5B and C) (25). We previously speculated that this in vitro deviation might arise from ‘entanglement’ of the disordered N-terminal tail of hUNG2 with the second uracil target site because the deviation was not observed with the catalytic domain (1,25,34). Omitting the non-ideal data point at 10 bp spacing for the in vitro data, we fit the cellular and in vitro translocation data to a Gaussian distribution (see Materials and Methods). From this analysis, mean translocation distances for hUNG2 of 37 ± 2 for the cell based measurements and 22 ± 2 and 8 ± 3 bp for the in vitro measurements in the presence and absence of PEG8K were obtained (Figure 5C).

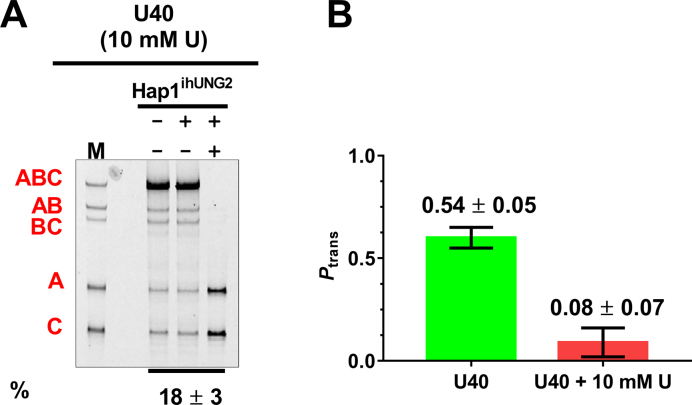

Is DNA translocation associative or dissociative in cells?

The primary tool for determining if translocation follows an associative or dissociative pathway in vitro is the uracil trapping method (Figure 1A) (34). This approach relies on the rapid diffusion of the small molecule inhibitor to the enzyme active site while the enzyme is in a short-lived dissociative transfer state, during which its uracil binding site is exposed. In the presence of high concentrations of uracil, the enzyme is trapped and unable to successfully complete dissociative transfers, but the associative pathway remains unaffected. In principle, the same method should work in cells because uracil is a membrane permeable molecule and is largely non-toxic to cells within our experimental timeframe. To test this approach, we transfected U40 into Hap1ihUNG2 cells and switched the medium to DMEM-P with or without 10 mM uracil. After two hours, we transfected cells for 4 h and then induced hUNG2 expression with doxycycline for another 8 h, after which cells were harvested and subjected to electrophoretic analysis as described above (Figure 6A). The longer eight-hour time frame was required because uracil is a competitive inhibitor of hUNG2 and less free enzyme was available to react with substrate, which provides evidence that the uracil concentration is significantly elevated inside the cell under these conditions. Comparison of the translocation efficiencies in the presence and absence of 10 mM uracil showed that the efficiency dropped from Ptrans = 0.54 in the absence of uracil to Ptrans = 0.08 ± 0.06 in its presence (Figure 6B). These results suggest that essentially all of the transfers followed the dissociative pathway and that associative transfers are negligible over a 40 bp site spacing. Although these results are in complete accord with the in vitro effects of uracil, we cannot definitively exclude that some unexpected mechanism is giving rise to the observed results.

Figure 6.

Measuring the contribution of dissociative and associative site transfers in cells. (A) Culturing of Hap1ihUNG2 cells with media containing 10 mM uracil beginning 2 h prior to transfection of substrate U40 and continuing throughout the experiment nearly abolished translocation by hUNG2. The induction time was extended to 8h to obtain a measurable extent of uracil excision due to the expected inhibition of hUNG2 by uracil (25,34). The reaction extent (in percent) is shown at the bottom of the gel. (B) Translocation efficiencies in the presence and absence of 10 mM uracil in the culture media.

DISCUSSION

This study culminates a series of systematic investigations aimed at unraveling the nature of DNA translocation by human uracil DNA glycosylase. The previous in vitro studies explored the singular and combined effects on UNG activity of electrostatic interactions between the protein and DNA, molecular crowding, and the effect of high concentrations of bulk DNA that approximate the nuclear DNA density (1,24). Based on our parallel studies with hOGG1 DNA glycosylase, we expect these conclusions to be broadly applicable to the search mechanism of many if not all DNA glycosylases.

It is useful to briefly summarize the in vitro behaviour of hUNG2 so that the cellular results can be placed in context. For hUNG2, non-specific DNA binding is driven by the entropically favourable release of monovalent cations from the DNA ion cloud, an effect that is lessened as the bulk monovalent ion concentration increases (41). In contrast, when hUNG2 encounters a base pair containing uracil, it adopts a conformation where binding is driven mostly by non-electrostatic interactions (41). Thus, in the absence of crowding, high concentrations of monovalent ions reduce translocation on non-specific DNA, but have little impact on the formation of the specific complex. The significant effect of macromolecular crowding in vitro is to confine the enzyme to the DNA volume and counteract the deleterious effect of salt on translocation (24).

Does the intracellular DNA translocation and repair kinetics of hUNG2 conform with expectations based on in vitro experiments? A comparison of the mean translocation distances between the cellular, in vitro crowding and non-crowding conditions clearly indicates that the nuclear environment substantially enhances the processivity of the damage search process (Figure 5C). Given the favorable effects of macromolecule crowding on in vitro translocation, we surmise that enhanced translocation in the cell nucleus also arises from crowding. Nevertheless, even with assistance from macromolecular crowding in the cell, hUNG2 does not slide over a 40 bp length of DNA without at least one micro-dissociation step (‘hop’) as suggested by the uracil trapping results (Figure 6B). Thus, just as in previous test tube experiments, we conclude that associative transfers in the nuclear compartment are operative only over very short distances (<10 bp), but play an essential role in damage recognition by increasing the search footprint beyond a single base pair. In summary, the major mechanism of translocation in the nucleus and in vitro is frequent dissociative transfers punctuated by short-range associative transfers that are enhanced by the cage provided by macromolecular crowding.

A striking aspect of the nuclear translocation results is that there is no evidence for competitive binding of nuclear proteins to the probe DNA despite the high macromolecule concentration. Although a fraction of the probe DNA in the nucleus could be sequestered from hUNG2 by protein binding, the translocation results require that once hUNG2 encounters a free probe DNA and excises the first uracil, it is largely unimpeded in its location of the second uracil (as compared to the in vitro Ptrans values in the absence of protein competitors). In the likely event that other proteins are bound between the two widely spaced uracil sites (40 and 80 bp), the proteins must be efficiently bypassed by the dissociative transfer mechanism. Such efficient bypass of bound proteins and other obstacles has precedence in vitro for hOGG1 and AAG human DNA glycosylases (2,42). The current findings suggest that similar bypass events occur efficiently in the nucleus and are essential for damage site location. It is worth noting that our previous in vitro translocation measurements with uracilated DNA bound in mononucleosomes showed no evidence for processivity (43), which was attributed to occlusion of nearby uracil sites during the short diffusive time frame where translocation takes place. Thus, if a fraction of the total probe DNA used in this study is chromatinized, this fraction of the DNA must be small or completely unreactive in order to account for the levels of translocation measured here in cells.

Our cellular measurements allow us to evaluate how the cellular rate of uracil excision from our DNA probes compares with in vitro expectations and if these rates are compatible with efficient repair of genomic uracils. The observed rate of uracil excision in Hap1ihUNG2 cells (∼5000 uracils excised per cell in 6h) is equivalent to that achieved by a time-averaged integrated concentration of free 〈[hUNG2]free〉 = 140 pM (25 hUNG2 molecules per nucleus; see Supplemental Information). The estimated 〈[hUNG2]free〉 is 1/20 000 of the time-averaged integrated concentration of total hUNG2 in Hap1ihUNG2 cells (3 μM). Although there is uncertainty in estimating the free enzyme concentration, the experimental results and calculation require that the vast majority of the total enzyme is sequestered in non-specific complexes with genomic DNA, proteins or other cellular metabolites. The estimated concentration of 〈[hUNG2]free〉 is consistent with the other evidence supporting single-encounter conditions and indicates that the free enzyme concentration is about 1000-fold less than the intracellular concentration of the transfected probe DNA (200 nM, 20 000 molecules/cell). Although the overexpressed enzyme concentration exceeds that of the endogenous by ∼10-fold, the results indicate that a relatively high copy number of the enzyme is required to maintain a small free enzyme fraction that is competent for uracil excision.

Is the free hUNG2 concentration in wild-type Hap1 cells sufficient for excision of genomic uracils? Previous studies have measured the steady-state level of uracil in genomic DNA in various cell lines with a rounded average value of ∼1000 uracils/genome (44,45). The average free hUNG2 concentration in a Hap1wt cell is ∼14 pM, which would be sufficient to excise 500 uracils in 6 h based on our data and calculations (Supplementary Information). This activity meets the requirement that an efficient DNA repair glycosylase should be able to react at a sufficient rate to remove damage that accumulates within one cell cycle (≈24 h for Hap1 cells). We note that this simple calculation does not take into account that hUNG2 expression is upregulated during S phase and that at least some of the nuclear enzyme is associated with the replication fork.

These findings show how a DNA glycosylase has evolved to search DNA in the most efficient manner possible, taking advantage of the crowded nuclear environment to overcome unfavorable salt effects and promote effective dissociative transfers on DNA. Such a mechanism allows a limited amount of free enzyme to move as rapidly as possible in the cell using free diffusion and yet stay in the vicinity of the DNA when it is encountered such that minimal time is spent searching regions of the nucleus that do not contain DNA.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are contained within the paper and its supplementary information files. Raw source files are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Author contributions: The JHMI microscopy core facility provided access to the ZEISS LSM700 confocal microscope, which was obtained with the support of a National Institutes of Health major instrumentation grant (S10-OD016374).

A.E. performed all experiments and data analysis and contributed to writing and editing the manuscript. G.R. performed part of the in vitro measurements of B-hUNG2 translocation. B.P.W. purified B-hUNG2 and edited the manuscript. P.A.C. provided scientific insights and edited the manuscript. J.T.S. conceived the approach and edited the manuscript.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR online.

FUNDING

National Institutes of Health [RO1-GM056834 to J.T.S., RO1-CA74305 to P.A.C., T32-GM8403, F32-GM119230, T32-CA9110 to B.P.W.]. Funding for open access charge: National Institute of Health Grant RO1-GM056834 [90059802].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cravens S.L., Stivers J.T.. Comparative effects of ions, molecular crowding, and bulk DNA on the damage search mechanisms of hOGG1 and hUNG. Biochemistry. 2016; 55:5230–5242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rowland M.M., Schonhoft J.D., McKibbin P.L., David S.S., Stivers J.T.. Microscopic mechanism of DNA damage searching by hOGG1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 42:9295–9303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Esadze A., Kemme C.A., Kolomeisky A.B., Iwahara J.. Positive and negative impacts of nonspecific sites during target location by a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein: origin of the optimal search at physiological ionic strength. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 42:7039–7046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zandarashvili L., Esadze A., Vuzman D., Kemme C.A., Levy Y., Iwahara J.. Balancing between affinity and speed in target DNA search by zinc-finger proteins via modulation of dynamic conformational ensemble. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015; 112:E5142–E5149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cuculis L., Abil Z., Zhao H., Schroeder C.M.. Direct observation of TALE protein dynamics reveals a two-state search mechanism. Nat. Commun. 2015; 6:7277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pollak A.J., Chin A.T., Reich N.O.. Distinct facilitated diffusion mechanisms by E. coli Type II restriction endonucleases. Biochemistry. 2014; 53:7028–7037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hammar P., Leroy P., Mahmutovic A., Marklund E.G., Berg O.G., Elf J.. The lac repressor displays facilitated diffusion in living cells. Science. 2012; 336:1595–1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bonnet I., Biebricher A., Porte P.L., Loverdo C., Benichou O., Voituriez R., Escude C., Wende W., Pingoud A., Desbiolles P.. Sliding and jumping of single EcoRV restriction enzymes on non-cognate DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008; 36:4118–4127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wishart D.S., Jewison T., Guo A.C., Wilson M., Knox C., Liu Y., Djoumbou Y., Mandal R., Aziat F., Dong E. et al. . HMDB 3.0—the human metabolome database in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:D801–D807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Markx G.H.D., Davey C. L.. The dielectric properties of biological cells at radiofrequencies: applications in biotechnology. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 1999; 25:161–171. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Banipal T.S., Kaur D., Banipal P.K.. Apparent molar volumes and viscosities of some amino acids in aqueous sodium acetate solutions at 298.15 K. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 2004; 49:1236–1246. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jenkins H.D.B., Marcus Y.. Viscosity B-coefficients of ions in solution. Chem Rev. 1995; 95:2695–2724. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Konopka M.C., Shkel I.A., Cayley S., Record M.T., Weisshaar J.C.. Crowding and confinement effects on protein diffusion in vivo. J. Bacteriol. 2006; 188:6115–6123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mourao M.A., Hakim J.B., Schnell S.. Connecting the dots: the effects of macromolecular crowding on cell physiology. Biophys. J. 2014; 107:2761–2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Minton A.P. The influence of macromolecular crowding and macromolecular confinement on biochemical reactions in physiological media. J. Biol. Chem. 2001; 276:10577–10580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stivers J.T. Extrahelical damaged base recognition by DNA glycosylase enzymes. Chemistry. 2008; 14:786–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Krokan H.E., Otterlei M., Nilsen H., Kavli B., Skorpen F., Andersen S., Skjelbred C., Akbari M., Aas P.A., Slupphaug G.. Properties and functions of human uracil-DNA glycosylase from the UNG gene. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 2001; 68:365–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Doseth B., Visnes T., Wallenius A., Ericsson I., Sarno A., Pettersen H.S., Flatberg A., Catterall T., Slupphaug G., Krokan H.E. et al. . Uracil-DNA glycosylase in base excision repair and adaptive immunity: species differences between man and mouse. J. Biol. Chem. 2011; 286:16669–16680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krokan H.E., Bjoras M.. Base excision repair. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013; 5:a012583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Friedman J.I., Stivers J.T.. Detection of damaged DNA bases by DNA glycosylase enzymes. Biochemistry. 2010; 49:4957–4967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Buechner C.N., Maiti A., Drohat A.C., Tessmer I.. Lesion search and recognition by thymine DNA glycosylase revealed by single molecule imaging. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:2716–2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hedglin M., O’Brien P.J.. Human alkyladenine DNA glycosylase employs a processive search for DNA damage. Biochemistry. 2008; 47:11434–11445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schonhoft J.D., Stivers J.T.. DNA translocation by human uracil DNA glycosylase: the case of single-stranded DNA and clustered uracils. Biochemistry. 2013; 52:2536–2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cravens S.L., Schonhoft J.D., Rowland M.M., Rodriguez A.A., Anderson B.G., Stivers J.T.. Molecular crowding enhances facilitated diffusion of two human DNA glycosylases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:4087–4097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rodriguez G., Esadze A., Weiser B.P, Schonhoft J.D., Cole P.A., Stivers J.T.. Disordered N-terminal domain of human uracil DNA glycosylase enhances DNA translocation. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017; 12:2260–2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shvets A.A., Kolomeisky A.B.. Crowding on DNA in protein search for targets. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016; 7:2502–2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Weil A.F., Ghosh D., Zhou Y., Seiple L., McMahon M.A., Spivak A.M., Siliciano R.F., Stivers J.T.. Uracil DNA glycosylase initiates degradation of HIV-1 cDNA containing misincorporated dUTP and prevents viral integration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013; 110:E448–E457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mirny L., Slutsky M., Wunderlich Z., Tafvizi A., Leith J., Kosmrlj A.. How a protein searches for its site on DNA: the mechanism of facilitated diffusion. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 2009; 42:29. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gorman J., Wang F., Redding S., Plys A.J., Fazio T., Wind S., Alani E.E., Greene E.C.. Single-molecule imaging reveals target-search mechanisms during DNA mismatch repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012; 109:E3074–E3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Slutsky M., Mirny L.A.. Kinetics of protein-DNA interaction: facilitated target location in sequence-dependent potential. Biophys. J. 2004; 87:4021–4035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Friedman J.I., Majumdar A., Stivers J.T.. Nontarget DNA binding shapes the dynamic landscape for enzymatic recognition of DNA damage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009; 37:3493–3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cuculis L., Abil Z., Zhao H.M., Schroeder C.M.. TALE proteins search DNA using a rotationally decoupled mechanism. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016; 12:831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mahmutovic A., Berg O.G., Elf J.. What matters for lac repressor search in vivo–sliding, hopping, intersegment transfer, crowding on DNA or recognition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:3454–3464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schonhoft J.D., Stivers J.T.. Timing facilitated site transfer of an enzyme on DNA. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012; 8:205–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Porecha R.H., Stivers J.T.. Uracil DNA glycosylase uses DNA hopping and short-range sliding to trap extrahelical uracils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008; 105:10791–10796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Grogan B.C., Parker J.B., Guminski A.F., Stivers J.T.. Effect of the thymidylate synthase inhibitors on dUTP and TTP pool levels and the activities of DNA repair glycosylases on uracil and 5-fluorouracil in DNA. Biochemistry. 2011; 50:618–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bennett S.E., Mosbaugh D.W.. Characterization of the Escherichia coli uracil-DNA glycosylase inhibitor protein complex. J. Biol. Chem. 1992; 267:22512–22521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hagen L., Kavli B., Sousa M.M., Torseth K., Liabakk N.B., Sundheim O., Pena-Diaz J., Otterlei M., Horning O., Jensen O.N. et al. . Cell cycle-specific UNG2 phosphorylations regulate protein turnover, activity and association with RPA. EMBO J. 2008; 27:51–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Carter R.J., Parsons J.L.. Base excision repair, a pathway regulated by posttranslational modifications. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2016; 36:1426–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Weiser B.P., Stivers J.T., Cole P.A.. Protein semi-synthesis to characterize phospho-regulation of human UNG2. Biophys. J. 2017; 113:393–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cravens S.L., Hobson M., Stivers J.T.. Electrostatic properties of complexes along a DNA glycosylase damage search pathway. Biochemistry. 2014; 53:7680–7692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hedglin M., O’Brien P.J.. Hopping enables a DNA repair glycosylase to search both strands and bypass a bound protein. ACS Chem. Biol. 2010; 5:427–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ye Y., Stahley M.R., Xu J., Friedman J.I., Sun Y., McKnight J.N., Gray J.J., Bowman G.D., Stivers J.T.. Enzymatic excision of uracil residues in nucleosomes depends on the local DNA structure and dynamics. Biochemistry. 2012; 51:6028–6038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pettersen H.S., Sundheim O., Gilljam K.M., Slupphaug G., Krokan H.E., Kavli B.. Uracil-DNA glycosylases SMUG1 and UNG2 coordinate the initial steps of base excision repair by distinct mechanisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007; 35:3879–3892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Krokan H.E., Drablos F., Slupphaug G.. Uracil in DNA—occurrence, consequences and repair. Oncogene. 2002; 21:8935–8948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are contained within the paper and its supplementary information files. Raw source files are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.