Abstract

This work aimed at evaluating the performance of three different intensity‐modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) treatment planning systems (TPSs) — KonRad, XiO and Prowess — for selected pediatric cases. For this study, 11 pediatric patients with different types of brain, orbit, head and neck cancer were selected. Clinical step‐and‐shoot IMRT treatment plans were designed for delivery on a Siemens ONCOR accelerator with 82‐leaf multileaf collimators (MLCs). Plans were optimized to achieve the same clinical objectives by applying the same beam energy and the same number and direction of beams. The analysis of performance was based on isodose distributions, dose‐volume histograms (DVHs) for planning target volume (PTV), the relevant organs at risk (OARs), as well as mean dose , maximum dose , 95% dose , volume of patient receiving 2 and 5 Gy, total number of segments, monitor units per segment (MU/Segment), and the number of MU/cGy. Treatment delivery time and conformation number were two other evaluation parameters that were considered in this study. Collectively, the Prowess and KonRad plans showed a significant reduction in the number of MUs that varied between 1.8% and 61.5% for the different cases, compared to XiO. This was reflected in shorter treatment delivery times. The percentage volumes of each patient receiving 2 Gy and 5 Gy were compared for the three TPSs. The general trend was that KonRad had the highest percentage volume, Prowess showed the lowest . The KonRad achieved better conformality than both of XiO and Prowess. Based on the present results, the three treatment planning systems were efficient in IMRT, yet XiO showed the lowest performance. The three TPSs achieved the treatment goals according to the internationally approved standards.

Keywords: KonRad, XiO, Prowess, IMRT

I. INTRODUCTION

A tremendous evolution in treatment process occurred in recent years. This allowed the delivery of the desired radiation dose distribution to target tissue, while delivering an acceptable radiation dose to the surrounding normal tissues with greater dose gradients and tighter margins. The treatment planning system (TPS) has a central role in the application of IMRT technique. A modern TPS has more sophisticated calculation algorithms, providing more accurate dose calculation capabilities, especially for the small beams associated with IMRT delivery techniques. Automated optimization routines used in conjunction with inverse planning are available to help define the multileaf collimator delivery configurations.( 1 , 2 )

Reported comparisons between TPSs included different parameters such as the accuracy of calculations, implementation and commissioning algorithms used in the optimization process, and the clinical functionality of the plan. Haslam et al. (3) compared the isocenter dose calculated by each of a commercial IMRT treatment planning system and an independent monitor unit verification calculation software in order to estimate the tolerance for monitor unit calculations. Pflugfelder et al. (4) proposed an improved optimization algorithm that could reach the same objective function value six times faster than commercial ones. Petric et al. (5) compared BrainScan TPS (BrainLAB, Feldkirchen, Germany) to Eclipse/Helios TPS (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA) in terms of implementation and commissioning, dose optimization, and plan assessment. Their results referred to an inadequacy of the Eclipse TPS to accurately calculate dose for highly modulated fields. Comparison between TPSs based on the evaluation of clinical functionality of the plan was rare especially in the pediatric field. (6)

One important factor in the comparison of TPSs is the time of radiation delivery to patients. Cancer patients may have difficulties lying on the treatment couch for long periods of time during the radiation delivery. Shortening the IMRT treatment time decreases the risk that patients involuntarily move during radiation therapy. It also minimizes the risk of decreased tumor cell killing potentially associated with delivery times in the range of 15ñ45 min. (7) Shortening the IMRT treatment time is highly desirable, especially for pediatric patients. (8)

Although IMRT in pediatric cases is definitely more complicated than in adults, only few studies comparing different commercial planning systems for IMRT in pediatric patients do exist. Therefore, the present study is concerned with introducing an experience with some pediatric indications that were chosen to represent common cases seen in the brain, orbit, and head and neck regions.

The objective of this work is to evaluate the performance of three different IMRT treatment planning systems (TPSs), Siemens KonRad version 2.2.23, Elekta XiO version 4.4, and Prowess Panther version 5, for brain, orbit, and head and neck cancer patients.

II. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The CT image sets for 11 pediatric patients, presenting different types of brain, orbit, head and neck cancers, were sent through the department network system (LANTIS Oncology Management System) to three different (TPSs), Siemens KonRad version 2.2.23 Siemens, Malvern, PA), Elekta XiO version 4.4 (Elekta CMS, Maryland Heights, MO), and Prowess Panther version 5 (Prowess inc., Concord, CA). In Table 1, a summary of the diagnosis, dose prescriptions, and clinical objectives (CObj) for organs at risk (OAR) is presented. All of the dose constraints reported here are specific to pediatric cases and are more restrictive than those used for adults.( 9 , 10 )

Table 1.

A summary of the diagnosis, dose prescriptions, and clinical objectives (CObj) for organs at risk (OAR) of the investigated cases.

| Case 1 | ||

| Low‐grade Glioma | Diagnosis | |

|

|

Radiotherapy dose prescription | |

|

|

Target volumes | |

| Eye mean dose , Cochlea mean dose Brain stem maximum dose | Organs at risk dose objectives | |

| 7 fields with gantry angles: 0, 51, 103, 154, 206, 257, 308 | Beam arrangement | |

| Case 2 | ||

| Parotid Carcinoma | Diagnosis | |

| Gy, 1.8 Gy/fraction | Radiotherapy dose prescription | |

|

|

Target volumes | |

| Spinal cord maximum dose , Parotid mean dose , Brain stem maximum dose | Organs at risk dose objectives | |

| 6 fields with gantry angles: 27, 129, 180, 231, 282, 333 | Beam arrangement | |

| Case 3 | ||

| Pituitary Adenoma | Diagnosis | |

| Gy, 2 Gy/fraction | Radiotherapy dose prescription | |

|

|

Target volumes | |

| Eye mean dose , Brain stem maximum dose | Organs at risk dose objectives | |

| 7 fields with gantry angles: 0, 51, 103, 154, 206, 257, 308 | Beam arrangement | |

| Case 4 | ||

| Retinoblastoma | Diagnosis | |

| Gy, 1.8 Gy/fraction | Radiotherapy dose prescription | |

|

|

Target volumes | |

| Eye mean dose , Lacrimal gland maximum dose , Brain stem maximum dose | Organs at risk dose objectives | |

| 8 fields with gantry angles: 27, 78, 231, 282, 333, with couch angle zero, and 270,315,45 with couch angle 90 | Beam arrangement | |

| Case 5 | ||

| Parotid carcinoma | Diagnosis | |

| Gy, 1.8 Gy/fraction | Radiotherapy dose prescription | |

|

|

Target volumes | |

| Spinal cord maximum dose Brain stem maximum dose | Organs at risk dose objectives | |

| 6 fields with gantry angles: 27, 78, 129, 180, 220, 333 | Beam arrangement | |

| Case 6 | ||

| High‐risk Medulloblastoma (Posterior fossa) | Diagnosis | |

| Gy, 1.8 Gy/fraction. (Precribed dose is only the boost dose which was used in the IMRT plan.) | Radiotherapy dose prescription | |

|

|

Target volumes | |

| Eye mean dose , Cochlea mean dose Optic nerve maximum dose | Organs at risk dose objectives | |

| 7 fields with gantry angles: 27, 78, 129, 180, 231, 282,333 | Beam arrangement | |

| Case 7 | ||

| Low‐risk Medulloblastoma (Posterior fossa) | Diagnosis | |

| Gy, 1.8 Gy/fraction (Prescribed dose is only the boost dose which was used in the IMRT plan.) | Radiotherapy dose prescription | |

|

|

Target volumes | |

| Pituitary mean dose , Cochlea mean dose Brain stem maximum dose | Organs at risk dose objectives | |

| 7 fields with gantry angles: 0, 51, 103, 154, 206, 257, 308 | Beam arrangement | |

| 7 fields with gantry angles: 0, 51, 103, 154, 206, 257, 308 | Beam arrangement | |

| Case 8 | ||

| Nasolaboil Rhabdomyosarcoma | Diagnosis | |

| Gy, 1.8 Gy/fraction | Radiotherapy dose prescription | |

|

|

Target volumes | |

| Eye mean dose Optic nerve maximum dose | Organs at risk dose objectives | |

| 7 fields with gantry angles: 0, 40, 80, 120, 240, 280, 320 | Beam arrangement | |

| Case 9 | ||

| Rhabdomyosarcoma(RMS) | Diagnosis | |

| Gy, 1.8 Gy/fraction | Radiotherapy dose prescription | |

|

|

Target volumes | |

| Eye mean dose , Parotid mean dose Brain stem maximum dose | Organs at risk dose objectives | |

| 7 fields with gantry angles: 27, 78, 129, 180, 231, 282, 333 | Beam arrangement | |

| Case 10 | ||

| Ependymoma | Diagnosis | |

| Gy, 1.8 Gy/fraction | Radiotherapy dose prescription | |

|

|

Target volumes | |

| Eye mean dose , Cochlea mean dose Brain stem maximum dose | Organs at risk dose objectives | |

| 7 fields with gantry angles: 27, 78, 129, 180, 231, 282, 333 | Beam arrangement | |

| Case 11 | ||

| Maxillary Sarcoma | Diagnosis | |

| Gy, 2 Gy/fraction | Radiotherapy dose prescription | |

|

|

Target volumes | |

| Eye mean dose , Parotid, mean dose Brain stem maximum dose | Organs at risk dose objectives | |

| 9 fields with gantry angles: 0, 40, 80, 120, 160, 200, 240, 280, 320 | Beam arrangement |

The clinical IMRT treatment plans were designed using the three treatment planning systems as step‐and‐shoot IMRT plans for delivery on the same machine, a Siemens ONCOR accelerator (Siemens, Malvern, PA) with an 82‐leaf MLC. Using the same machine nutralizes any limitation, due to machine configuration such as the leaf width or radiation leakage. On each of the three planning systems, three objectives were fulfilled before the plan was accepted: i) target coverage heterogeneity within and of the prescribed dose (according to International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements (ICRU)), ii) OAR sparing to at least the limits stated in Table 1, and iii) sparing of healthy tissue (the CT dataset patient volume minus the volume of the largest target). (11) The number of fields and the beam geometry were fixed in order to avoid variability in the results due to different beam arrangements.

Both KonRad and XiO treatment planning systems have optimization engines which rely on physical optimization. The dose calculation was performed using either pencil beam (PB) in the case of KonRad,( 12 , 13 ) or superposition algorithm in the case of XiO. Both treatment planning systems used the dose volume constraints and minimumñmaximum dose constraints. (14)

Prowess uses the direct aperture optimization (DAO), so it has convolution/superposition dose calculation engine, which includes all the delivery constraints within the optimization process, as well as the weights of the individual aperture shapes. There is no conversion from fluence maps to aperture shapes. (15)

The number of intensity levels used by the three systems to discretize individual beam fluence was determined manually in order to achieve the clinical goals with the fewest number of segments.

Special care was taken during this pre‐optimization phase in order to ensure that an adequate number of calculation points were defined within each structure, as this would influence the optimization results.

A. Evaluation tools

The analysis was based on isodose distributions and on dose‐volume histograms (DVHs) for planning target volume (PTV) and the relevant OARs, as well as mean dose, maximum dose, (dose to 95% of the PTV). (16) Volumes receiving 2 Gy and 5 Gy were calculated and compared. Also the treatment delivery time, total number of segments, MU/segment, and the number of MU/cGy were investigated. (17)

Conformation number (CN) as described by Riet et al. (18) was used because it took into account irradiation of the target volume and irradiation of healthy tissues. This number was defined as follows:

| (1) |

where , target volume covered by the reference isodose, , and volume of the reference isodose. The used reference isodose was the isodose 95% of the prescribed dose (according to the ICRU). The first fraction of this equation defines the quality of coverage of the target (local control), while the second fraction defines the volume of healthy tissue receiving a dose greater than or equal to the prescribed reference dose. The CN ranges from 0 to 1, where 1 is the ideal value.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was performed as a statistical model used to study the significance level all through the data, and a p‐value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. In the study, alpha .

Finally, the delivered doses had a complex, nonintuitive relationship to the number of monitor units. It was also impossible to predict the exact combination of field segments or the leaf motion patterns. Therefore, all the IMRT plans, which were performed using the MLC for the production of fluence modulations, should establish a precise and reliable method for the dosimetric verification of IMRT plans. (19) Since a verification of dose distributions within a real patient was not possible, the phantom substitution method was often used. (20)

III. RESULTS & DISCUSSION

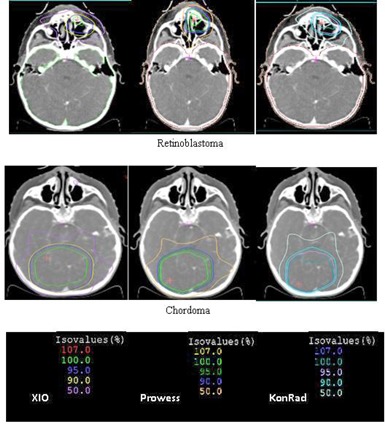

Figure (1) shows the dose distributions obtained from the three TPSs (XiO, KonRad, and Prowess) for some of the investigated cases. The dose distributions are presented as a color isodose lines overlaid on the transverse CT slice through the isocenter. Comparing the dose distribution through the patient volume (cut‐by‐cut) makes it possible to qualitatively analyze the different degrees of conformal avoidance, the extension of the low‐dose areas, the degree of uniformity of doses within the PTVs, and the potential presence of hot spots. The dose distributions obtained from the three TPSs are found to be similar with minor differences. All of the plans achieve similar coverage of the PTVs. It is also demonstrated that although the dose distributions are similar, the relative beam weights of the fields can be different, depending on the treatment planning system.

Figure 1. Dose distributions for some of the investigated cases from the three TPSs: KonRad (results in the right column), Prowess (middle column), XiO (left column).

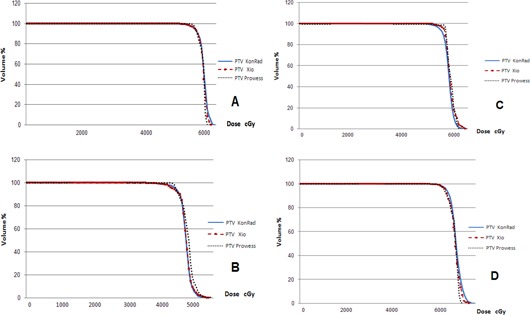

Figure (2) presents a comparison of the DVHs of some of the investigated cases for the PTVs from the three TPSs. Such a comparison provides more quantitative results compared to the qualitative comparison of the dose distributions. All plans of the TPSs achieve similar PTV coverage. In most instances, a slightly steeper dose gradient in the case of the Prowess plans is noticed. Although the PTV coverage is similar for the three TPSs, the DVHs for OARs differ between the plans generated by the different planning systems.

Figure 2. A comparison of the DVHs of some of the investigated cases for the PTVs from the three TPSs: KonRad (solid lines), XiO (dashed lines), Prowess (dotted lines).

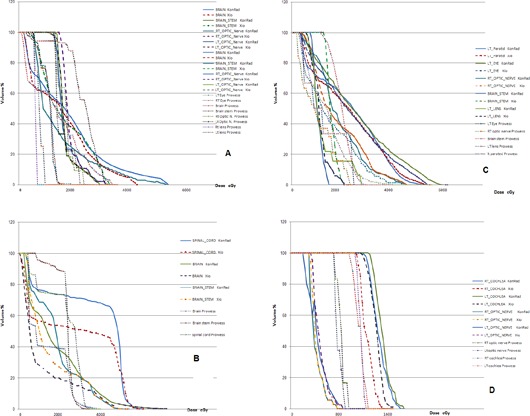

Figure (3) shows the DVHs calculated by each of the three TPSs for some of the investigated cases. Several remarks can be drawn from each case. For patient 1, the three planning systems can easily reach the clinical objectives for the optic nerve. A better sparing of both cochleas is obtained by Prowess while maintaining the same improvement in both of the optic nerves. This reflects an ability of the Prowess TPS to achieve high conformality than KonRad and XiO. In case of patient 2, the objectives selected for the eye (that was partially included in the target) are fulfilled by the three TPSs. The high number of OARs in patient 3 does not cause any problem and the clinical objectives are respected, but it comes at the expense of MU especially in case of XiO. For patient 4, both XiO and Prowess show a better sparing in the entire OARs than KonRad. In patient 5, on average, all of the clinical objectives are fulfilled, despite the fact that for the maximum dose of most of the OARs, KonRad shows minor violations. In patient 6, the DVHs of Prowess for left parotid, left eye, show minor differences between the three TPSs, while the KonRad plan shows improved sparing of the brain stem. In the plan of patient 7, all of the clinical objectives are achieved with the minor exception of the parotid where the mean dose was 26.6 Gy instead of 26 Gy in the KonRad plan. Doses greater than 50 Gy are observed for the brain stem, exceeding the tolerance, with the KonRad plan in case of patient 8 because it fails to achieve a sharp dose falloff outside the target volume. For patient 9, XiO is able to reach the objectives for the spinal cord and brain stem associated with a consistently better management of the maximum dose and a relatively low‐dose bath.

Figure 3. A comparison of the DVHs for the OARs from the KonRad (solid line), Prowess (gradient line), and XiO (dashed line) systems for some of the investigated cases.

Tables 2(a) and (b) show the prescription dose, mean dose , the dose received by 95% of the volume , and maximum dose to the PTVs for the XiO, KonRad. and Prowess plans. For most cases, the values for are similar among the three systems; the differences do not exceed 2.1 Gy.

Table 2(a).

The prescription dose, mean dose , the dose received by 95% of the volume , and maximum dose to the PTVs for the XiO, Prowess, and KonRad plans.

| Maximum Dose (Gy) |

|

Mean Dose (Gy) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KonRad | Prowess | XiO | KonRad | Prowess | XiO | KonRad | Prowess | XiO | Prescribed dose (Gy) | Tumor Site | |

| 61 | 58.8 | 62 | 51.2 | 51.3 | 51.1 | 53.9 | 53 | 52.5 | 54 | Low‐grade Glioma | |

| 69.6 | 71 | 69 | 61.6 | 61.5 | 62 | 64.4 | 66 | 63.9 | 64.8 | Parotid Carcinoma | |

| 53.6 | 53.9 | 54 | 47.8 | 47.5 | 47.7 | 50 | 51.5 | 50 | 50 | Pituitary Adenoma | |

| 51.62 | 51.7 | 52 | 42.8 | 42.7 | 43.1 | 44.75 | 46 | 45 | 45 | Retinoblastoma | |

| 73.3 | 70.7 | 71.4 | 61.6 | 61.5 | 62 | 65.1 | 66.6 | 65.3 | 64.8 | Parotid Carcinoma | |

| 22.3 | 21.6 | 22.3 | 19 | 18.8 | 19.1 | 19.7 | 20.2 | 19.8 | 19.8 | High‐risk Medulloblastoma | |

| 36.2 | 35.9 | 36.4 | 30.7 | 30.8 | 30.9 | 32.5 | 33.3 | 32.3 | 32.4 | Low‐risk Medulloblastoma | |

| 41.4 | 42 | 41.5 | 34.4 | 34.2 | 34 | 36.3 | 38 | 36.6 | 36 | Nasolaboil RMS | |

| 60 | 62 | 57.6 | 47.8 | 47.8 | 47.9 | 50.6 | 51.8 | 51 | 50.4 | Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) | |

| 68.8 | 65.8 | 63 | 56.43 | 56.4 | 56.2 | 59.9 | 61 | 59 | 59.4 | Ependymoma | |

| 73.5 | 68.7 | 69.8 | 57 | 57 | 57.1 | 59.9 | 61.6 | 60 | 60 | Maxillary Sarcoma | |

Table 2(b).

The dose range, mean percentage of dose, mean percentage of the dose received by 95% of the volume, and mean percentage of maximum dose to the PTVs for the XiO, Prowess, and KonRad plans.

| Dose Range (Gy) |

Mean Percentage of Dose

|

Mean Percentage of

|

Mean Percentage of Maximum Dose (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19.8 ‐ 64.8 | XiO | Prowess | KonRad | XiO | Prowess | KonRad | XiO | Prowess | KonRad | ||

| 99.9 | 102.4 | 100.1 | 95.3 | 95 | 95.2 | 112 | 112.3 | 113.8 | |||

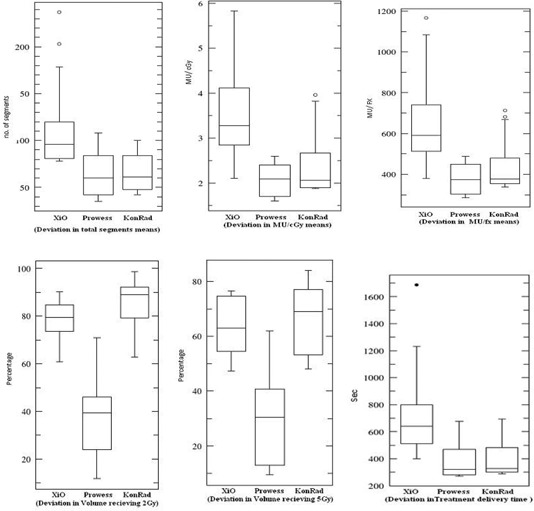

Table 3 lists the results of the beam segmentation optimization. The Prowess and KonRad plans show a statistically significant reduction in the number of MUs (between 1.8% and 61.5%) for the different cases. A reduction between 12.5% and 63.5% in the number of beam segments is also noticed.

Table 3.

Monitor unit per fraction and total segments in each of the studied cases using XiO, Prowess, and KonRad TPSs.

| Total Segments | MU/fx | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KonRad | Prowess | XiO | KonRad | Prowess | XiO | Tumor Site |

| 67 | 35 | 96 | 432 | 284 | 513 | Low‐grade Glioma |

| 51 | 60 | 88 | 355 | 304 | 523 | Parotid Carcinoma |

| 48 | 84 | 79 | 381 | 489 | 548 | Pituitary Adenoma |

| 57 | 72 | 120 | 377 | 463 | 595 | Retinoblastoma |

| 61 | 48 | 81 | 372 | 411 | 379 | Parotid Carcinoma (carsinoma carcinoma) |

| 71 | 84 | 109 | 481 | 428 | 742 | High‐risk Medulloblastoma (Posterior fossa) |

| 48 | 42 | 114 | 342 | 327 | 724 | Low‐risk Medulloblastoma (Posterior fossa) |

| 42 | 49 | 78 | 338 | 361 | 591 | Nasolaboil RMS |

| 100 | 98 | 203 | 713 | 374 | 911 | Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) |

| 84 | 42 | 96 | 363 | 292 | 512 | Ependymoma |

| 100 | 108 | 237 | 682 | 449 | 1167 | Maxillary Sarcoma |

| 66.3 | 65.6 | 118 | 439.6 | 380 | 655 | Mean |

| 20.5 | 25 | 52.8 | 134.2 | 72.6 | 222 | SD |

| 7.864 | 9.5 | F‐test | ||||

| 0.002 | 0.001 | p‐value | ||||

In this case, as a “post‐hoc” analysis of the group means, it was found that the XiO and Prowess data means differed by 275 units, the XiO and KonRad data means differed by 215 units, and the Prowess and KoRad data means differed by only 60 units. The standard error of each of these differences is 82. Thus the XiO is strongly different from Prowess and KonRad, as the mean difference is more times the standard error. Thus we can be confident that the population mean of the XiO data differs from the population mean of the Prowess and Konrad data. However, there is no evidence that the Prowess and KoRad have different population means from each other, as their mean difference is comparable to the standard error.

Table 4 lists the number of MU/cGy (modulation factor) and the treatment delivery time (sec) for each of the investigated cases. Fogliata et al.(6) determined a mean value of 2.56 MU/cGy for eight TPSs, where KonRad produced the lowest value of 1.9 MU/cGy. Comparable average values are also reported in the present study (2.4 MU/cGy for KonRad, 2.1 MU/cGy for Prowess, and a higher value of 3.6 MU/cGy for XiO).

Table 4.

The number of MU/cGy (modulation factor) and the treatment delivery time (sec) using XiO, Prowess, and KonRad TPSs.

| MU/cGy | Treatment delivery time (sec). | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KonRad | Prowess | XiO | KonRad | Prowess | XiO | Tumor Site |

| 2.4 | 1.6 | 2.85 | 291 | 270 | 512 | Low‐grade Glioma |

| 1.97 | 2.3 | 2.91 | 323 | 305 | 646 | Parotid Carcinoma |

| 1.9 | 2.5 | 2.74 | 289 | 281 | 401 | Pituitary Adenoma |

| 2.09 | 2.6 | 3.31 | 320 | 309 | 794 | Retinoblastoma |

| 2.07 | 1.7 | 2.11 | 368 | 343 | 570 | Parotid Carcinoma carsinoma carcinoma |

| 2.67 | 2.4 | 4.12 | 450 | 432 | 800 | High‐risk Medulloblastoma (Posterior fossa) |

| 1.9 | 1.8 | 4.02 | 326 | 321 | 620 | Low‐risk Medulloblastoma (Posterior fossa) |

| 1.88 | 2 | 3.28 | 302 | 280 | 429 | Nasolaboil RMS |

| 3.96 | 2.1 | 5.06 | 695 | 677 | 1036 | Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) |

| 2.02 | 1.6 | 2.84 | 483 | 469 | 641 | Ependymoma |

| 3.41 | 2.2 | 5.83 | 612 | 598 | 1687 | Maxillary Sarcoma |

| 2.4 | 2.1 | 3.6 | 405.4 | 389.5 | 740 | Mean |

| 0.7 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 139.2 | 139 | 363 | SD |

| 10.87 | 7.575 | F‐test | ||||

| 0.0003 | 0.002 | p‐value | ||||

The reduction in the combination of the number of MUs and the number of segments results in significantly shorter delivery times (between 24.7% and 64.5%). as shown in Table 4. The higher number of monitor units (MU), longer delivery time, and higher number of beam segments (delivering higher leakage radiation to the patient) is a disadvantage in XiO compared to Prowess and KonRad. This disadvantage of XiO may be reflected mainly in a possible increase in radiation‐induced secondary malignancies, caused mostly by the increased volume of patient receiving low‐dose levels. (21) Although this issue is not yet certain, it should be taken into consideration in the case of pediatric patients. If true, this problem may represent a major factor limiting the use of XiO in pediatric oncology, knowing that pediatric treatments are delicate where enhanced radiation sensitivity is expected. Children are more sensitive than adults. Moreover, the effect of scattered radiation inside the patient is more significant in the small body of a child than in the large body of an adult. It has been reported that there is a genetic susceptibility of pediatric tissues to radiation‐induced cancer. (22)

Table 5 presents the average number of MUs per segment and the number of MUs for the longest and shortest segments in the calculated plans. The main difference between the three systems is that the Prowess plans include segments with very small number of MUs, which may affect the amount of radiation leakage.

Table 5.

The number of MUs per segment, and the number of MUs for the longest and shortest segments, in the calculated plans for XiO, Prowess, and KonRad TPSs.

| Longest Segment (MU) | Shortest Segment(MU) | MU/Segment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KonRad | Prowess | XiO | KonRad | Prowess | XiO | KonRad | Prowess | XiO | Tumor Site |

| 14 | 33 | 11.3 | 5.2 | 1 | 3.7 | 6.45 | 8 | 5.3 | Low‐grade Glioma |

| 14.1 | 25 | 14.5 | 6.2 | 2 | 2.9 | 7 | 8.6 | 5.9 | Parotid Carcinoma |

| 17 | 21 | 16.4 | 5 | 1 | 4.8 | 7.9 | 5.8 | 6.9 | Pituitary Adenoma |

| 17 | 30 | 13.3 | 4 | 1 | 2.9 | 6.6 | 6.4 | 5 | Retinoblastoma |

| 16 | 16 | 12.8 | 5 | 1 | 1.1 | 6.1 | 5 | 4.7 | Parotid Carcinoma |

| 12.5 | 17 | 22.7 | 5.7 | 1 | 3.4 | 6.8 | 5.1 | 6.8 | High‐risk Medulloblastoma |

| 14 | 22 | 15 | 6.2 | 1 | 3.7 | 7.1 | 7.8 | 6.4 | Low‐risk Medulloblastoma |

| 23.9 | 19 | 43.3 | 4.3 | 2 | 2.6 | 8 | 7.4 | 7.6 | Nasolaboil RMS |

| 13.2 | 33 | 13.1 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 7.1 | 3.8 | 4.5 | Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) |

| 10 | 21 | 13.3 | 3 | 1 | 3.4 | 4.3 | 7 | 5.3 | Ependymoma |

| 20 | 16 | 27.8 | 5 | 1 | 2.1 | 6.8 | 4.2 | 4.9 | Maxillary Sarcoma |

| 15.6 | 23 | 18.5 | 4 | 1.2 | 3 | 6.7 | 6.3 | 5.8 | Mean |

| 3.8 | 6.4 | 9.6 | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 1 | 1.6 | 1 | SD |

A feature common to practically all IMRT plans is that a relatively large volume would receive a low dose of radiation. This low‐dose volume may not cause acute or subacute clinical morbidity, but may potentially be carcinogenic, especially in children. Some models of radiation carcinogenesis suggest that the dose‐response relationship is linear up to a dose of 6 Gy, where it then reaches a plateau. (21) The percentage volumes of each patient receiving 2 Gy and 5 Gy may be important in this context. Therefore, the present study reports the percentage volumes of each patient receiving 2 Gy and 5 Gy for comparison between the three TPSs for each treatment plan in Table 6. Results show statistically significant values . As a general trend, KonRad has the highest volume receiving in excess of 2 and 5 Gy, and Prowess has the lowest. Also, KonRad achieves better conformality than either XiO and Prowess, although it is not considered statistically significant.

Table 6.

The values of the conformation number and the volumes receiving greater than 2 Gy and greater than 5 Gy in percentage using XiO, Prowess, and KonRad TPSs.

|

|

|

CN | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor Site | XiO | Prowess | KonRad | XiO | Prowess | KonRad | XiO | Prowess | KonRad | ||

| Low‐grade Glioma | 63 | 49 | 90.87 | 53.14 | 42.5 | 69.09 | 0.7 | 0.65 | 0.73 | ||

| Parotid Ccarcinoma | 79.4 | 46 | 98.67 | 68.68 | 38 | 78.10 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.71 | ||

| Pituitary Adenoma | 84.7 | 39.4 | 91.14 | 71.89 | 32.4 | 73.41 | 0.7 | 0.75 | 0.68 | ||

| Retinoblastoma | 90.2 | 41 | 81.88 | 56.86 | 30.5 | 48.08 | 0.69 | 0.71 | 0.7 | ||

| Parotid Carcinoma | 73.6 | 29 | 79.31 | 63.08 | 25 | 58.26 | 0.69 | 0.81 | 0.71 | ||

| High‐risk | 86.8 | 14.3 | 92.17 | 76.63 | 12 | 77.02 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.76 | ||

| Medulloblastoma | |||||||||||

| Low‐risk | 84.4 | 11.8 | 95.86 | 75.20 | 9.4 | 84.03 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.69 | ||

| Medulloblastoma | |||||||||||

| Nasolaboil RMS | 79.6 | 24 | 88.97 | 47.35 | 13 | 53.19 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.72 | ||

| Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) | 76.9 | 42.9 | 74.85 | 74.71 | 40.7 | 69.07 | 0.68 | 0.7 | 0.69 | ||

| Ependymoma | 60.9 | 71 | 62.94 | 54.47 | 62 | 53.08 | 0.71 | 0.7 | 0.73 | ||

| Maxillary Sarcoma | 76.4 | 34.5 | 80.89 | 62.64 | 30 | 65.12 | 0.75 | 0.83 | 0.75 | ||

| Mean | 77.8 | 36.6 | 85 | 64.1 | 30.5 | 66.2 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.72 | ||

| SD | 9.3 | 16.8 | 10.5 | 10.1 | 15.6 | 11.7 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.03 | ||

| F‐test | 47.4 | 27.4 | 0.4 | ||||||||

| p‐value | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.59 | ||||||||

The radiation conformation number of the resultant treatment plans are computed using Eq. (1). (18)

This study investigates the usability of the KonRad, Prowess, and XiO TPSs for pathologies which are more complicated in nature, rare, and more challenging (such as pediatric cases) especially in the situation of brain, orbit, and head and neck, where treatment planning requires particular skills and is bounded by dose‐limiting constraints often severely different from the ones applied to adults.

For the 11 cases studied in this work, the three treatment planning systems under comparison allow for the design of plans mostly respecting the initial treatment planning objectives with a range of differences. The plans generate equivalent dose distributions, which are generally expected to correlate with significant reduction of acute and late toxicity, as already documented in pediatric radiation oncology. (23) Each system may provide better capabilities in some clinical requirements and strategies and lower capabilities in others.

In pediatric radiation oncology the number of MU/cGy is a highly important issue in terms of possible induction of secondary malignancies. So the delivered MU to young patients should be as low as possible to minimize that risk. This factor gives an advantage for Prowess, which has a statistically significant mean modulation factor of 2.1 MU/cGy over KonRad (2.4 MU/cGy) and XiO (3.3 MU/cGy). The variation in means between the different groups of data is shown in (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. A graphical comparison that provides a visual guide of the deviations in the means between the different groups of data.

This study evaluates, globally, the performances of the three TPSs without explicitly correcting for limitations in dose calculation engines since, in this way, it is possible to reproduce more precisely potential clinical conditions. In addition, it would be substantially impossible to disentangle the optimization phase from the dose calculation engines. In fact, in the XiO TPS, the multileaf segmentation engines include some considerations on scattered radiation from the linac head which are intimately connected with the final dose calculation engines. Therefore, no true factorization process is possible to limit a comparison of performances to the optimization phase.

IV. CONCLUSIONS

The three treatment planning systems can technically succeed in managing the very restrictive conditions of the clinical goals according to the internationally approved standards and are, in principle, valid for application in pediatric practice. Nevertheless, the XiO TPS shows some drawbacks compared to KonRad and Prowess; the latter two show more favorable results.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lahanas M, Schreibmann E, Baltas D. Multiobjective inverse planning for intensity modulated radiotherapy with constraint‐free gradient‐based optimization algorithms. Phys Med Biol. 2003; 48 (17): 2843–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yu CX, Amies CJ, Svatos M. Planning and delivery of intensity‐modulated radiation therapy. Med Phys. 2008; 35 (12): 5233–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Haslam JJ, Bonta DV, Lujan AE, Rash C, Jackson W, Roeske JC. Comparison of dose calculated by an intensity modulated radiotherapy treatment planning system and an independent monitor unit verification program. JACMP. 2003; 4 (3): 224–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pflugfelder D, Wilkens JJ, Nill S, Oelfke U. A comparison of three optimization algorithms for intensity modulated radiation therapy. Z Med Phys. 2007; 18 (2): 111–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Petric MP, Clark BG, Robar JL. A comparison of two commercial treatment‐planning systems to IMRT. JACMP. 2005; 6 (3): 63–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fogliata A, Nicolini G, Alber M, et al. On the performances of different IMRT treatment planning systems for selected paediatric cases. Radiat Oncol. 2007; 2: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Crooks SM, McAven LF, Robinson DF, Xing L. Minimizing delivery time and monitor units in static IMRT by leaf‐sequencing. Phys Med Biol. 2002; 47 (17): 3105–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cooper JS, Fu K, Marks J, Silverman S. Late effects of radiation therapy in the head and neck region. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995; 31 (1): 1141–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Emami B, Lyman J, Brown A, et al. Tolerance of normal tissue to therapeutic irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991; 21 (1): 109–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Milano MT, Constine LS, Okunieff P. Normal tissue tolerance dose metrics for radiation therapy of major organs. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2007; 17 (2): 131–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stein J, Mohan R, Wang XH, et al. Number and orientations of beams in intensity‐modulated radiation treatments. Med Phys. 1997; 24 (2): 149–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bortfeld T, Schlegel W, Rhein B. Decomposition of pencil beam kernels for fast dose calculations in three‐dimensional treatment planning. Med Phys. 1993; 20 (2 Pt 1): 311–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Knöös T, Ceberg C, Weber L, Nilsson P. The dosimetric verification of a pencil beam based treatment planning system. Phys Med Biol. 1994; 39 (10): 1609–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bortfeld T, Stein J, Preise K. Clinically relevant intensity modulation optimization using physical criteria. Proceedings of the XIIth International Conference on the Use of Computers in Radiation Therapy. Madison: Medical Physics Publishing; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jiang Z, Earl MA, Zhang GW, Yu CX, Shepard DM. An examination of the number of required apertures for step‐and‐shoot IMRT. Phys. Med Biol. 2005; 50 (23): 5653–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Verhey LJ. Comparison of three‐dimensional conformal radiation therapy and intensity‐modulated radiation therapy systems. Semin Radiat Oncol. 1999; 9 (1): 78–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dai J and Zhu Y. Minimizing the number of segments in a delivery sequence for intensity‐modulated radiation therapy with a multileaf collimator. Med Phys. 2001; 28 (10): 2113–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vvanít Riet A, Mak AC, Moerland MA, Elders LH, van der Zee W. A conformation number to quantify the degree of conformality in brachytherapy and external beam irradiation: application to the prostate. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997; 37 (3): 731–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Both S, Alecu IM, Stan AR, et al. A study to establish reasonable action limits for patient‐specific quality assurance in intensity‐modulated radiation therapy. JACMP. 2007; 8 (2): 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xing L, Curran B, Hill R, et al. Dosimetric verification of a commercial inverse treatment planning system. Phys Med Biol. 1999; 44 (2): 463–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hall EJ and Wuu CS. Radiation‐induced second cancers: the impact of 3D‐CRT and IMRT. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003; 56 (1): 83–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hall EJ. Intensity‐modulated radiation therapy, protons, and the risk of second cancers. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006, 65 (1): 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Teh BS, Mai WY, Grant WH 3rd, et al. Intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) decreases treatment‐related morbidity and potentially enhances tumor control. Cancer Invest. 2002; 20 (4): 437–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]