Abstract

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is associated with various extrahepatic manifestations, which are correlated with poor outcomes, and thus increase the morbidity and mortality of chronic hepatitis C (CHC). Therefore, understanding the internal linkages between systemic manifestations and HCV infection is helpful for treatment of CHC. Yet, the mechanism by which the virus evokes the systemic diseases remains to be elucidated. In the present study, using gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and signaling pathway impact analysis (SPIA), a comprehensive analysis of micro-array data of mRNAs was conducted in HCV-infected and -uninfected Huh7.5 cells, and signaling pathways (which are significantly activated or inhibited) and certain molecules (which are commonly important in those signaling pathways) were selected. Forty signaling pathways were selected using GSEA, and eight signaling pathways were selected with SPIA. These pathways are associated with cancer, metabolism, environmental information processing and organismal systems, which provide important information for further clarifying the intrinsic associations between syndromes of HCV infection, of which seven pathways were not previously reported, including basal transcription factors, pathogenic Escherichia coli infection, shigellosis, gastric acid secretion, dorso-ventral axis formation, amoebiasis and cholinergic synapse. Ten genes, SOS1, RAF1, IFNA2, IFNG, MTHFR, IGF1, CALM3, UBE2B, TP53 and BMP7 whose expression may be the key internal driving molecules, were selected using the online tool Anni 2.1. Furthermore, the present study demonstrated the internal linkages between systemic manifestations and HCV infection, and presented the potential molecules that are key to those linkages.

Keywords: hepatitis C virus, extrahepatic manifestation, pathway, molecular mechanism

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the leading cause of serious liver diseases, including fibrosis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, which affect >185 million people worldwide and >3 million people are newly infected each year (1). However, chronic HCV infection is associated with various extrahepatic manifestations, and it is estimated that a high proportion of patients with chronic hepatitis C (CHC) (~90%) may develop at least one extrahepatic manifestation during the course of the disease (2,3). Certain extrahepatic manifestations are most likely associated with the HCV infection, such as mixed cryoglobulinemic syndrome and B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, while other manifestations are potentially associated with HCV infection, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, membrane proliferative glomerulonephritis, neurological impairments, sicca syndrome, porphyria cutanea tarda, lichen planus, autoantibodies, moorens corneal ulcers and cardiovascular events (3). These linkages are confirmed following antiviral treatment, which partly ameliorate the above-mentioned syndromes. However, those extrahepatic manifestations are, in turn, correlated with poor outcomes, including accelerated progression of hepatic fibrosis, reduced sustained virological response rates, and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), resulting in increasing the morbidity and mortality of CHC (2).

Yet, the mechanism by which the virus evokes the systemic diseases, including thyroid, cardiovascular, renal, eye and skin diseases, and lymphomas and diabetes, remain to be elucidated (4). Certainly, the mechanisms causing the extrahepatic effects of HCV infection are likely multifactorial, and include direct or indirect effects (2,3,5). Previous studies indicate that HCV directly infects and replicates in various types of extrahepatic cell, and thus induces extrahepatic manifestations, although increasing evidence indicates that it also results from endocrine effects or a heightened immune reaction with systemic effects (6). Furthermore, successful eradication of HCV with antiviral drugs was shown to improve certain extrahepatic effects, which are not always associated with the severity of liver diseases (7). Thus, understanding the internal linkages between systemic manifestations and HCV infection is useful for improving the treatment of CHC in future.

With the rapid development of microarray techniques, increasing applications of those high-throughput methods reveal the pathogenic mechanism of the HCV infection (8–10). Previous studies demonstrated that the HCV infection affects signaling pathways associated with diseases, including type II diabetes signaling, hepatic cholestasis and cancer (11–14). However, the results are not entirely consistent with one another. The variability may result from various factors, such as the cell lines, cells with different statuses, virus genotypes and viral infectious dose. It may also result from the use of different microarray platforms and different algorithms (15). The methods of dealing with these data have recently been developed (16). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and signaling pathway impact analysis (SPIA), which are two mature algorithms and are used proverbially, consider a set of genes as a group in order to calculate the correlation with different phenotypes (17). In the present study, GSEA and SPIA were applied to compare the expression levels of mRNAs in HCV-infected and -uninfected cells. Using this method, signaling pathways associated with liver and extrahepatic diseases were selected, and the important molecules in those pathways were also demonstrated. These data will contribute to clarifying the internal driving factors contributing to the systemic diseases of HCV infection.

Materials and methods

Cells and treatments

Huh7.5 cells and plasmid pFL-J6/JFH/JC1 containing the full-length chimeric HCV complementary DNA (cDNA) were provided by Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Boston, MA, USA). HCV virus stock was prepared as previously described (18). Huh7.5 cells were infected with HCV virus stock (150 IU/cell) or virus mock stock (as a control). After 48 h, the culture supernatants were removed and the cells were lyzed directly with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and total intracellular RNAs were extracted accordingly. mRNA microarray was performed by Kangchen Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) using Agilent chips (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Each of the experiments was independently performed four times.

Data preprocess

All data obtained from the microarray chips were transferred to the genomic data structure format using the Biobase package in Bioconductor (version 3.1) (19). The data annotation was applied using the package, hgug4112a.db (20). Data from four arrays were combined and quantile normalized prior to analysis (21), then transformed to a log2 scale (22), and batch effects were removed using the sva package in Bioconductor (23).

GSEA

GSEA analysis of signaling pathways and genes was performed using the category package in version 3.1 of Bioconductor (24). The goal of GSEA analysis is to determine whether the members of a gene set 'S' are randomly distributed throughout the entire reference gene list 'L' or are primarily found at the top or bottom of the list. Gene sets represented by ≤5 genes were excluded. The t-statistic mean of the genes was computed in each Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway. The information regarding the pathways was obtained from KEGG.db in Bioconductor (25). Using a permutation test with 10,000 permutations, the cut-off of the significance level was determined as P<0.05 to indicate the significant signaling pathways associated with HCV infection.

SPIA

SPIA analysis was performed using the SPIA package in version 3.1 of Bioconductor (26). SPIA calculated the P-value combing the different expression gene data with the perturbation of signaling pathways. In this case, the different expression genes were confirmed by applying the limma package (27). Genes with P<0.05 by row t-test were selected. The detailed procedure of SPIA was performed according to a previous study (28).

Anni 2.1

The association between a gene and the HCV infection was analyzed using the online tool Anni 2.1 (http://biosemantics.org/index.php/software/anni). The calculation was performed as previously described (29). The entry of each pathway, such as map04010 for mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) signaling pathway was submitted, along with the key word 'HCV' as a pair to Anni 2.1. Anni 2.1 retrieves data from MEDLINE (https://www.medline.com) to score the association between HCV and each gene in these signaling pathways. The association score is based on concepts co-occurrences and a higher score indicates a greater association between a gene and HCV.

Pathview

The visualization of gene changing in signaling pathways was performed using the Pathview package in version 3.1 of Bioconductor (30).

Results

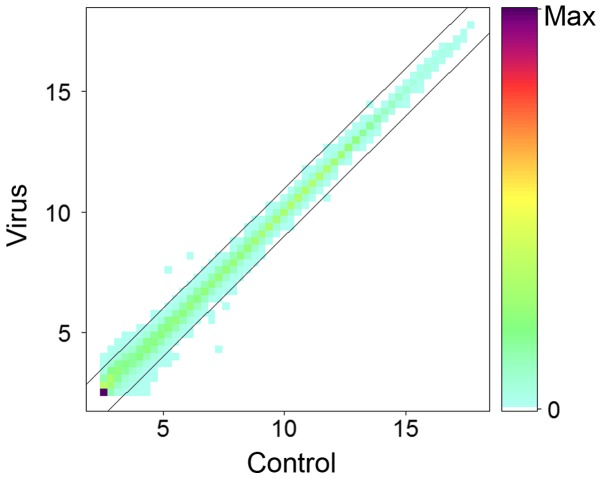

To investigate the internal driving factors contributing to systemic diseases of the HCV infection, Huh7.5 cells were infected with HCV genotype 2a (virus group) or virus mock stock (control group), and the intracellular total RNAs were extracted after 48 h. The level of mRNAs was determined using Agilent chips. Following normalization, the numerical average level of genes in virus and control groups at log2 scale was plotted (Fig. 1). Results indicated that the majority of genes remain unchanged >2-fold or <0.5-fold following infection with HCV, which is consistent with previous studies (31).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the mRNAs in HCV-infected and -uninfected Huh7.5 cells. Huh7.5 cells were infected with HCV virus stock at an infection dose of 150 IU/cell (virus) or with virus mock stock (control), cells were collected and RNAs were extracted for mRNA microarray assay following infection for 48 h. The changed expression levels >2-folds or <0.5-fold are presented. HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Subsequently, the P-values were calculated using GSEA or SPIA. In the results obtained with GSEA, 40 pathways were selected with P<0.05 (Table I), including signaling pathways with functions of human diseases, metabolism, organismal systems, cellular processes, genetic information processing and environmental information processing. Among them, 35 signaling pathways were inhibited and five signaling pathways were activated by the HCV infection, and hepatitis C and hedgehog signaling pathways were previously confirmed (32). However, in the result calculated with SPIA, only eight signaling pathways were selected (Table II), including gastric acid secretion, the MAPK signaling pathway, cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, dilated cardiomyopathy, amoebiasis, basal cell carcinoma, human T-cell leukemia virus type I infection and cholinergic synapse. However, apart from the gastric acid secretion pathway, these signaling pathways were not included in the results selected with GSEA.

Table I.

Pathways selected with gene set enrichment analysis.

| Name | P-value | Status | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell cycle | 0.042 | Inhibited | Cellular processes; cell growth and death |

| Adherens junction | 0.042 | Inhibited | Cellular processes; cellular community |

| Hedgehog signaling pathway | 0.014 | Activated | Environmental information processing; signal transduction |

| ErbB signaling pathway | 0.014 | Inhibited | Environmental information processing; signal transduction |

| Ubiquitin mediated proteolysis | 0.014 | Inhibited | Genetic information processing; folding, sorting and degradation |

| Basal transcription factors | 0.042 | Inhibited | Genetic information processing; transcription |

| Pathways in cancer | 0.014 | Inhibited | Human diseases; cancers |

| Prostate cancer | 0.014 | Inhibited | Human diseases; cancers |

| Melanoma | 0.014 | Inhibited | Human diseases; cancers |

| Non-small cell lung cancer | 0.014 | Inhibited | Human diseases; cancers |

| Bladder cancer | 0.014 | Inhibited | Human diseases; cancers |

| Thyroid cancer | 0.025 | Inhibited | Human diseases; cancers |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 0.027 | Inhibited | Human diseases; cancers |

| Small cell lung cancer | 0.027 | Inhibited | Human diseases; cancers |

| Pancreatic cancer | 0.029 | Inhibited | Human diseases; cancers |

| Colorectal cancer | 0.042 | Inhibited | Human diseases; cancers |

| Renal cell carcinoma | 0.043 | Inhibited | Human diseases; cancers |

| Glioma | 0.044 | Inhibited | Human diseases; cancers |

| Endometrial cancer | 0.045 | Inhibited | Human diseases; cancers |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 0.014 | Inhibited | Human diseases; immune diseases |

| Hepatitis C | 0.014 | Inhibited | Human diseases; infectious diseases |

| Bacterial invasion of epithelial cells | 0.027 | Inhibited | Human diseases; infectious diseases |

| Pathogenic Escherichia coli infection | 0.040 | Inhibited | Human diseases; infectious diseases |

| Shigellosis | 0.043 | Inhibited | Human diseases; infectious diseases |

| Histidine metabolism | 0.027 | Inhibited | Metabolism; amino acid metabolism |

| Tryptophan metabolism | 0.029 | Inhibited | Metabolism; amino acid metabolism |

| Nitrogen metabolism | 0.029 | Inhibited | Metabolism; energy metabolism |

| Glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis - heparan sulfate | 0.043 | Activated | Metabolism; glycan biosynthesis and metabolism |

| Glycosphingolipid biosynthesis - globo series | 0.045 | Activated | Metabolism; glycan biosynthesis and metabolism |

| One carbon pool by folate | 0.014 | Inhibited | Metabolism; metabolism of cofactors and vitamins |

| Porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism | 0.040 | Activated | Metabolism; metabolism of cofactors and vitamins |

| Dorso-ventral axis formation | 0.042 | Inhibited | Organismal systems; development |

| Vitamin digestion and absorption | 0.027 | Inhibited | Organismal systems; digestive system |

| Gastric acid secretion | 0.045 | Inhibited | Organismal systems; digestive system |

| Circadian rhythm-mammal | 0.031 | Inhibited | Organismal systems; environmental adaptation |

| Collecting duct acid secretion | 0.030 | Activated | Organismal systems; excretory system |

| Proximal tubule bicarbonate reclamation | 0.044 | Inhibited | Organismal systems; excretory system |

| Nucleotide oligomerization domain-like receptor signaling pathway | 0.042 | Inhibited | Organismal systems; immune system |

| Leukocyte transendothelial migration | 0.043 | Inhibited | Organismal systems; immune system |

| Neurotrophin signaling pathway | 0.027 | Inhibited | Organismal systems; nervous system |

Table II.

Pathways selected with signaling pathway impact analysis.

| Name | P-value | Status | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mitogen-activated protein kinases signaling pathway | 0.011 | Inhibited | Environmental information processing; signal transduction |

| Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction | 0.017 | Inhibited | Environmental information processing; signaling molecules and interaction |

| Basal cell carcinoma | 0.025 | Inhibited | Human diseases; cancers |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 0.021 | Activated | Human diseases; cardiovascular diseases |

| Amoebiasis | 0.023 | Inhibited | Human diseases; infectious diseases |

| Human T-cell leukemia virus type I infection | 0.039 | Inhibited | Human diseases; infectious diseases |

| Gastric acid secretion | 0.008 | Inhibited | Organismal systems; digestive system |

| Cholinergic synapse | 0.042 | Inhibited | Organismal systems; nervous system |

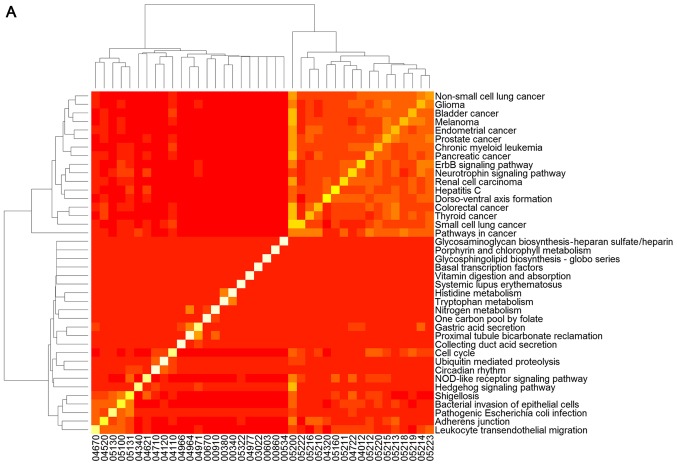

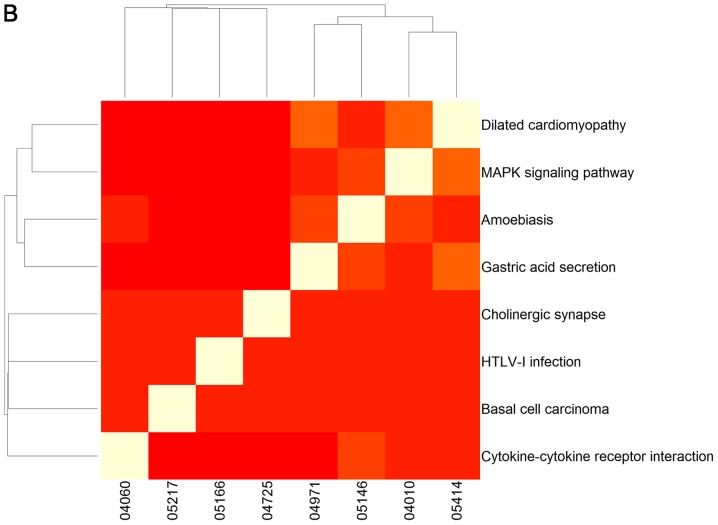

To clarify the association between signaling pathways, the overlap genes in signaling pathways were further assessed and heat-maps of the pathways were plotted (Fig. 2). The results clearly demonstrate that changed genes overlapped more in the two clusters of signaling pathways selected using GSEA (Fig. 2A). One cluster included the signaling pathway of hepatitis C and pathways predominantly associated with cancer, including non-small cell lung cancer, glioma, bladder cancer, melanoma, endometrial cancer, prostate cancer, chronic myeloid leukemia, pancreatic cancer, the ErbB and neurotrophin signaling pathways, renal cell carcinoma, dorso-ventral axis formation, colorectal cancer, thyroid cancer, small cell lung cancer, and pathways in cancer (Fig. 2A). The other cluster was comprised of the hedgehog signaling pathway, shigellosis, bacterial invasion of epithelial cells, pathogenic Escherichia coli infection, adherens junction and leukocyte transendothelial migration, which was predominantly associated with infection diseases (Fig. 2A). However, overlap genes between signaling pathways selected using GSEA were relatively few (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Heat map of signaling pathways selected with (A) gene set enrichment analysis and (B) signaling pathway impact analysis. The plot demonstrates the overlapping genes from the different signaling pathways. A white-red color scale depicts the number of overlapping genes in two different pathways (white, high; red, low).

To analyze the biological significance of these selected pathways, the average score of signaling pathways was calculated to evaluate the biological significance of the pathway and highlight the gene with the highest score in the signaling pathway using the online tool Anni 2.1. Six signaling pathways from SPIA and 11 signaling pathways from GSEA (pathways with P<0.025) were selected (Table III). The results demonstrated that the score of the prostate cancer signaling pathway was the highest, followed by the hepatitis C pathway, and SOS1 was the highest scoring gene and made the most contribution to six of the signaling pathways (Table III). However, the average score of signaling pathways identified by GSEA is higher than that identified by SPIA (0.0085 vs. 0.0045; P<0.025).

Table III.

Score of each signaling pathway and the highest score gene in the pathway.

| Signaling pathway | Algorithm | Score | Highest scoring gene |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prostate cancer | GSEA | 0.0219 | SOS1 |

| Hepatitis C | GSEA | 0.0135 | SOS1 |

| Non-small cell lung cancer | GSEA | 0.0103 | SOS1 |

| Bladder cancer | GSEA | 0.0102 | RAF1 |

| ErbB signaling pathway | GSEA | 0.0085 | SOS1 |

| Melanoma | GSEA | 0.0076 | RAF1 |

| Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction | GSEA | 0.0073 | IFNA2 |

| Pathways in cancer | GSEA | 0.0065 | SOS1 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | GSEA | 0.0059 | IFNG |

| Amoebiasis | SPIA | 0.0057 | IFNG |

| MAPK signaling pathway | SPIA | 0.0050 | SOS1 |

| One carbon pool by folate | GSEA | 0.0048 | MTHFR |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | SPIA | 0.0043 | IGF1 |

| Gastric acid secretion | SPIA | 0.0038 | CALM3 |

| Ubiquitin mediated proteolysis | GSEA | 0.0036 | UBE2B |

| Basal cell carcinoma | SPIA | 0.0036 | TP53 |

| Hedgehog signaling pathway | GSEA | 0.0036 | BMP7 |

MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinases; GSEA, gene set enrichment analysis.

Discussion

To understand the internal driving factors contributing to the systemic manifestation of the HCV infection, a comprehensive analysis was performed on microarray data of mRNAs in HCV-infected and -uninfected Huh7.5 cells using GSEA and SPIA, and 40 signaling pathways that were significantly activated or inhibited were selected using GSEA, and eight pathways that were significantly changed were selected using SPIA, although only one signaling pathway overlapped with GSEA. Indeed, there were few instances of overlapping signaling pathways in GSEA and SPIA, and similar differences were previously reported (15,33). The reason may be that GSEA and SPIA are based upon different theories. GSEA is based upon functional class scoring (FCS) methods. Compared with traditional over-representation analysis (ORA) methods, GSEA is accurate and meaningful as it does not ignore molecular measurements when identifying significant pathways. SPIA uses pathway topology (PT)-based methods. Compared with FCS methods, SPIA uses topology information of signaling pathways when identifying significant pathways. It is more accurate and meaningful than FCS methods. However, PT-based methods do have limitations, as the knowledge of signaling pathways is not fully understood and there is only fragmented knowledge. In addition, the integrity of topology information of signaling pathways will largely affect results. With improvement of annotations, PT-based methods are expected to become more valuable. In view of this, GSEA and SPIA algorithms were applied to demonstrate the signaling pathways in different landscapes. These pathways provided important clues for further clarifying the intrinsic associations between systemic syndromes of HCV infection.

Cryoglobulinemia, B-cell lymphoma and thyroid disorders are the major extrahepatic manifestations; however, the three disorders are not included in the KEGG pathway database, therefore they are not shown when applying KEGG-based statistics. The two algorithms, GSEA and SPIA, determine that certain signaling pathways include genes associated with these diseases. Types II and III cryoglobulinemia, which are strongly associated with HCV infection, tend to be associated with immune disease usually accompanied by abnormal antibodies (34). In the present results, systemic lupus erythematosus, nucleotide oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor signaling pathway and leukocyte transendothelial migration were observed. As the biological process by which HCV causes cryoglobulinemia is not fully understood, the present results may provide insight into the investigation of the internal driving factors related with the disease after HCV infection. B-cell lymphoma is a cancer of the B lymphocytes. In the present results, 15 signaling pathways of cancer were identified, notably the pathway termed 'pathways in cancer'. A previous study indicated that NOD-like receptors are key in human B lymphocytes (35). Certainly, NOD-like receptor signaling pathway was indeed selected out in our result. In addition to that, the signaling pathway of thyroid cancer was identified to include certain genes associated with thyroid disorders. Those results indicate that the present experiments and the algorithms are valuable.

HCV is the leading cause of HCC and its infection affects cancer-associated pathways. Following analysis with GSEA, 18 signaling pathways in the functional class of human diseases were selected, in which 13 signaling pathways are in the subclass of cancer, one signaling pathway is in the subclass of immune diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus) and four pathways are in the subclass of infectious diseases (Table I). In addition, cancer-associated pathways were selected using SPIA, although far fewer than with GSEA (Table II). However, the HCV infection often leads to abnormal metabolism (36). Indeed, certain metabolism pathways were selected using GSEA (Tables I and II). There are other syndromes in HCV-infected patients, such as left ventricular systolic, diastolic dysfunction and cardiac arrhythmias, although the intrinsic associations with HCV infection remain unclear (37). Signaling pathways were selected with GSEA or SPIA, which were involved with environmental information processing, organismal systems, and certain signaling pathways may have direct or indirect associations with HCV (Tables I and II).

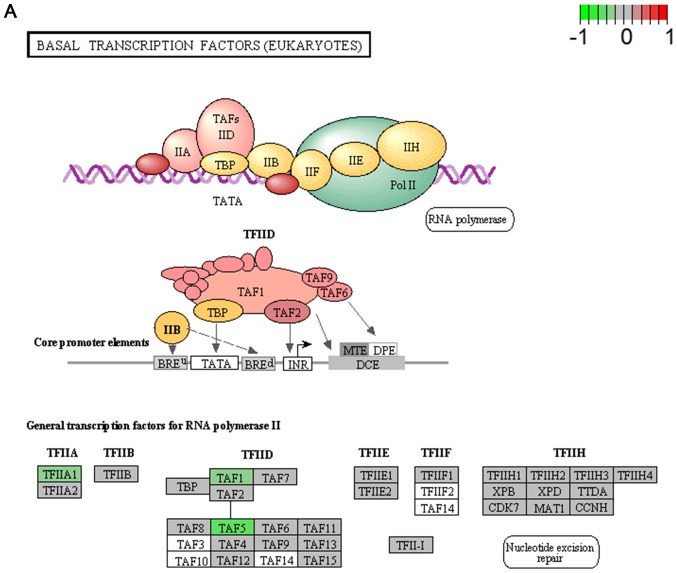

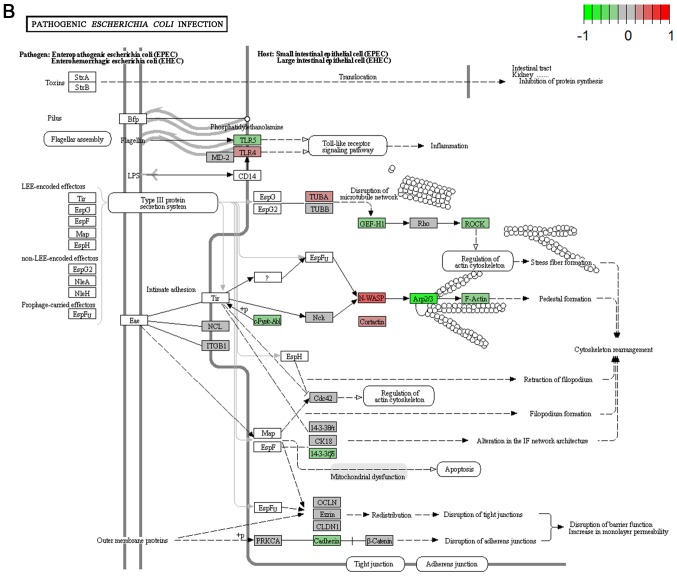

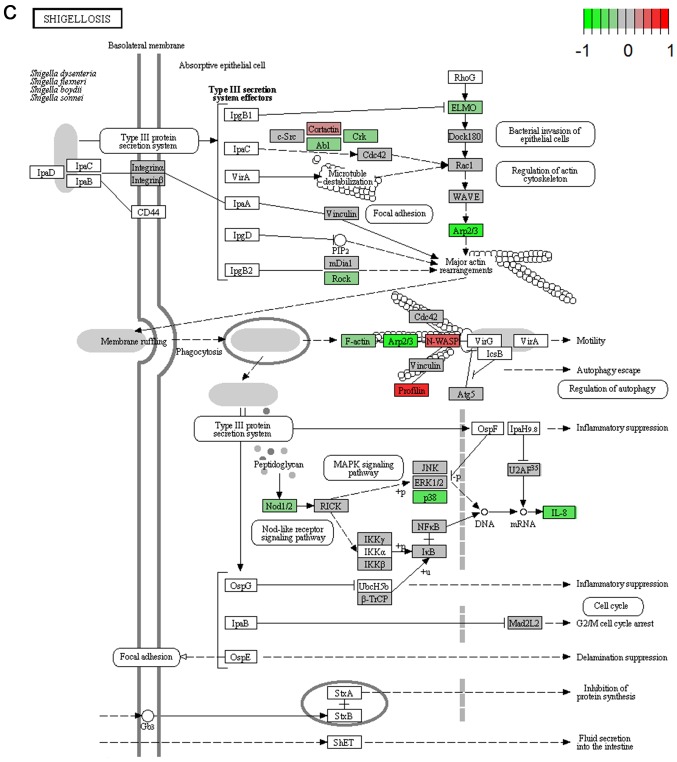

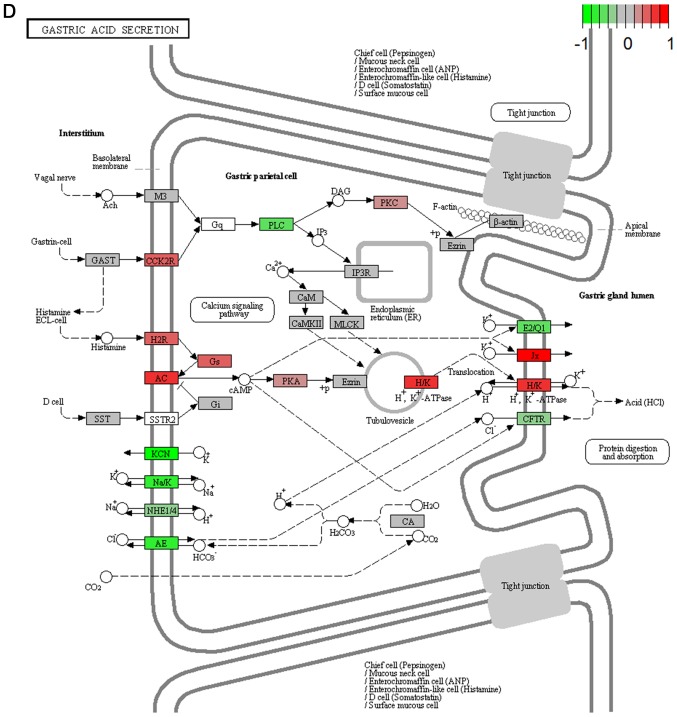

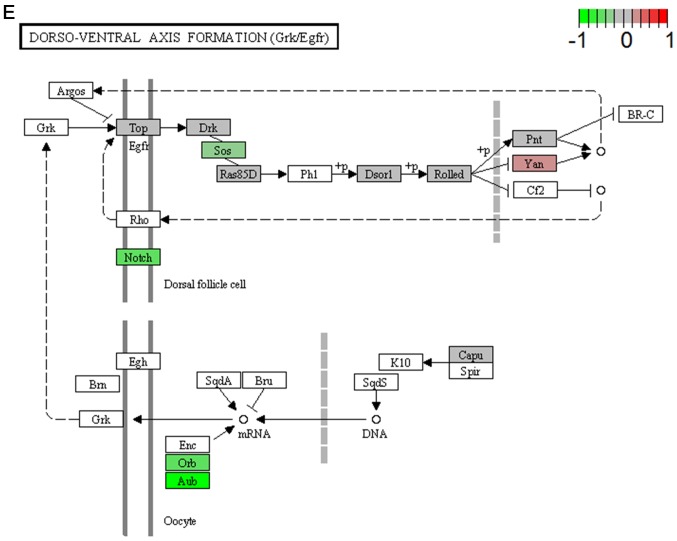

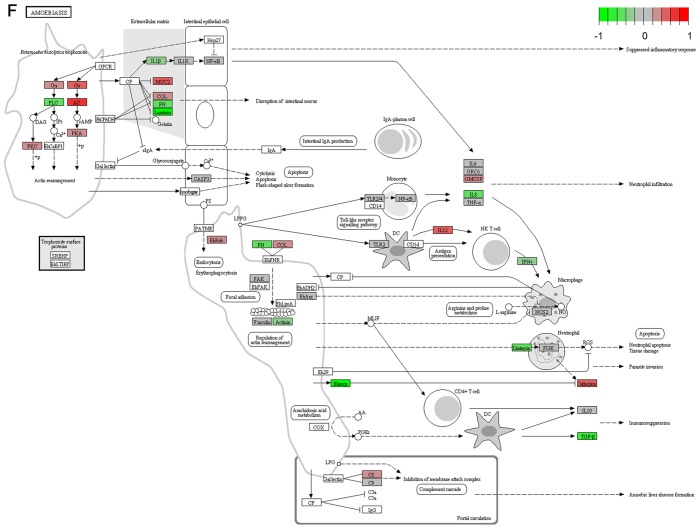

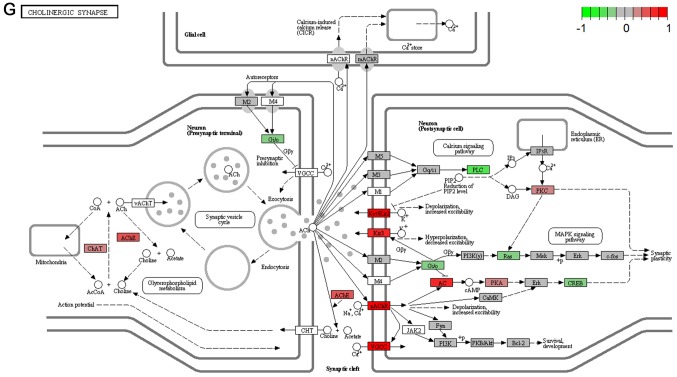

It's important to note that the majority of these signaling pathways have been reported to be associated with HCV infection (11–14), which confirmed the two algorithms are effective in selecting pathways. However, seven of the signaling pathways provide novel clues to demonstrate the driving factor for extrahepatic manifestations of HCV infection, including basal transcription factors (Fig. 3A), pathogenic Escherichia coli infection (Fig. 3B), shigellosis (Fig. 3C), gastric acid secretion (Fig. 3D), dorso-ventral axis formation (Fig. 3E), amoebiasis (Fig. 3F) and cholinergic synapse (Fig. 3G). Notably, the pathway of gastric acid secretion (Fig. 3D) was selected by the two algorithms in the present study. In this signaling pathway, genes are clearly influenced by the HCV infection (Fig. 3D). Gastric acid secretion is associated with liver cirrhosis caused by the hepatitis virus infection (38), and is also correlated with acute pancreatitis (39,40). Previous studies demonstrated that acute pancreatitis is associated with viral hepatitis (41–43), in particular, a case of acute pancreatitis was described with associated HCV infection (43). However, the direct associations between HCV infection and gastric acid secretion or acute pancreatitis require further experiments in order to be clarified. Basal transcriptional factors (Fig. 3A), also termed general transcription factors (GTFs), are a class of protein transcription factors, and the factors TFIIA, TFIIB, TFIID, TFIIE, TFIIF and TFIIH are required for RNA polymerase II to bind to a promoter (44). Certainly, HCV replication indeed influences these factors, it was reported that HCV protein, NS5A interacts with TFIID (45). In the present study, various factors of TFIIA and TFIID were inhibited by HCV infection. Shigellosis (Fig. 3C), amoebiasis (Fig. 3F) and pathogenic Escherichia coli infection (Fig. 3B) are three different types of infectious disease. No direct connection was reported between these infections and the HCV infection. However, certain viral infections may be a risk factor to other infections; for example, the HIV infection may be a risk factor for acquiring shigellosis (46–48). Cholinergic synapse (Fig. 3G) is predominantly about the biological process of acetylcholine (ACh). ACh participates in numerous functions, such as learning, memory, attention and motor control. Clinically, the HCV infection causes nervous system dysfunction, which is primarily caused by upregulation of the host immune response with production of autoantibodies, immune complexes and cryoglobulins (49); the present results may demonstrate a novel insight into this pathogenesis. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no evidence to indicate that dorso-ventral axis formation (Fig. 3E) is associated with the HCV infection.

Figure 3.

Visualized pathways of (A) basal transcription factors, (B) pathogenic Escherichia coli infection. Genes in red are upregulated and genes in green are downregulated. Genes in blue and pink are upregulated and downregulated but to a lesser degree. Genes in grey are not regulated significantly. Genes in white are these genes not counted in this microarray. (C) shigellosis, (D) gastric acid secretion. Genes in red are upregulated and genes in green are downregulated. Genes in blue and pink are upregulated and downregulated but to a lesser degree. Genes in grey are not regulated significantly. Genes in white are these genes not counted in this microarray. (E) dorso-ventral axis formation, (F) amoebiasis. Genes in red are upregulated and genes in green are downregulated. Genes in blue and pink are upregulated and downregulated but to a lesser degree. Genes in grey are not regulated significantly. Genes in white are these genes not counted in this microarray. (G) cholinergic synapse. Genes in red are upregulated and genes in green are downregulated. Genes in blue and pink are upregulated and downregulated but to a lesser degree. Genes in grey are not regulated significantly. Genes in white are these genes not counted in this microarray.

Using Anni 2.1, single genes were selected from the selected signaling pathways for further analysis (Table III). Those top genes selected with the Anni tool demonstrate their significance in the signaling pathways and associations with the HCV infection. However, the level of these does not necessarily change in the pathways, as the algorithm of the Anni tool did not consider the fold-changes of genes. Furthermore, those genes in Table III did not present obvious changes in the present experiments. However, the change in the protein levels cannot be excluded. SOS1, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Ras/Rac, was the highest scoring gene and contributed to six signaling pathways (Table III). Although no direct association has been reported between SOS1 and the HCV infection, it provides novel evidence to further illustrate the outcome that HCV infection causes HCC, as a previous study demonstrated that SOS1 is closely associated with cancer (50). The next highest scoring gene was Raf1, which is an enzyme in the extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 signaling pathway that performs a regulatory role (51). It was reported that constitutive expression of the HCV core results in a high basal activity of Raf1 (52) and knockdown of Raf1 inhibits HCV replication (53), indicating that Raf1 may be important in the HCV life cycle. The third was IFNA2, which is a gene encoded by prototypic human interferon α (IFNα). It is associated with antivirus activity, as the recombinant IFNα2 has been approved for the treatment of HCV and its pegylated forms (PEG-IFNα2) are the most widely administered anti-viral agents (54). Furthermore, IFNγ is a human IFN and contributes to auto-immune activities, and methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase, insulin-like growth factor and TP53 exhibit direct or indirect associations with HCC following infection with HCV (53–57). These data may provide further evidence to investigate the associations between the HCV infection and syndromes exhibited by patients. In addition, illustration of the underlying mechanisms of those molecules may provide potential targets for interrupting the internal driving factors contributing to the extrahepatic manifestations of the HCV infection.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated seven novel pathways for further clarifying the direct intrinsic factors contributing to systemic manifestations of the HCV infection, including basal transcription factors, pathogenic Escherichia coli infection, shigellosis, gastric acid secretion, dorso-ventral axis formation, amoebiasis and cholinergic synapse, and identified 10 genes, SOS1, RAF1, IFNA2, IFNG, MTHFR, IGF1, CALM3, UBE2B, TP53 and BMP7, whose expression may be key in those pathways.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81321004 and 81322050), the National Mega-Project for 'R&D for Innovative Drugs', Ministry of Science and Technology of China (grant no. 2012ZX09301-002-001), the Ministry of Education of China (grant no. NCET-12-0072). The authors would also like to thank Kangchen Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) for performing the mRNA microarray detection using Agilent chip technology.

References

- 1.El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1264–1273 e1261. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Negro F, Forton D, Craxi A, Sulkowski MS, Feld JJ, Manns MP. Extrahepatic morbidity and mortality of chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1345–1360. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang L, Marcell L, Kottilil S. Systemic manifestations of hepatitis C infection. Infect Agent Cancer. 2016;11:29. doi: 10.1186/s13027-016-0076-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sherman AC, Sherman KE. Extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C infection: Navigating CHASM. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015;12:353–361. doi: 10.1007/s11904-015-0274-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gill K, Ghazinian H, Manch R, Gish R. Hepatitis C virus as a systemic disease: Reaching beyond the liver. Hepatol Int. 2016;10:415–423. doi: 10.1007/s12072-015-9684-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zignego AL, Gragnani L, Piluso A, Sebastiani M, Giuggioli D, Fallahi P, Antonelli A, Ferri C. Virus-driven autoimmunity and lymphoproliferation: The example of HCV infection. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2015;11:15–31. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2015.997214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nuno Solinis R, Arratibel Ugarte P, Rojo A, Sanchez Gonzalez Y. Value of treating all stages of chronic hepatitis C: A comprehensive review of clinical and economic evidence. Infect Dis Ther. 2016;5:491–508. doi: 10.1007/s40121-016-0134-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee CM, Hung CH, Lu SN, Changchien CS. Hepatitis C virus genotypes: Clinical relevance and therapeutic implications. Chang Gung Med J. 2008;31:16–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waldron PR, Holodniy M. MicroRNA and hepatitis C virus - challenges in investigation and translation: A review of the literature. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;80:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahman W, Tu T, Budzinska M, Huang P, Belov L, Chrisp JS, Christopherson RI, Warner FJ, Bowden DS, Thompson AJ, et al. Analysis of post-liver transplant hepatitis C virus recurrence using serial cluster of differentiation antibody microarrays. Transplantation. 2015;99:e120–e126. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woodhouse SD, Narayan R, Latham S, Lee S, Antrobus R, Gangadharan B, Luo S, Schroth GP, Klenerman P, Zitzmann N. Transcriptome sequencing, microarray, and proteomic analyses reveal cellular and metabolic impact of hepatitis C virus infection in vitro. Hepatology. 2010;52:443–453. doi: 10.1002/hep.23733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blackham S, Baillie A, Al-Hababi F, Remlinger K, You S, Hamatake R, McGarvey MJ. Gene expression profiling indicates the roles of host oxidative stress, apoptosis, lipid metabolism, and intracellular transport genes in the replication of hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 2010;84:5404–5414. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02529-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papic N, Maxwell CI, Delker DA, Liu S, Heale BS, Hagedorn CH. RNA-sequencing analysis of 5′ capped RNAs identifies many new differentially expressed genes in acute hepatitis C virus infection. Viruses. 2012;4:581–612. doi: 10.3390/v4040581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walters KA, Syder AJ, Lederer SL, Diamond DL, Paeper B, Rice CM, Katze MG. Genomic analysis reveals a potential role for cell cycle perturbation in HCV-mediated apoptosis of cultured hepatocytes. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000269. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai B, Jiang X. Revealing biological pathways implicated in lung cancer from TCGA gene expression data using gene set enrichment analysis. Cancer Inform. 2014;13:113–121. doi: 10.4137/CIN.S13882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hira ZM, Gillies DF. A Review of feature selection and feature extraction methods applied on microarray data. Adv Bioinformatics. 2015;2015:198363. doi: 10.1155/2015/198363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braun R. Systems analysis of high-throughput data. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;844:153–187. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2095-2_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng ZG, Zhao ZY, Li YP, Wang YP, Hao LH, Fan B, Li YH, Wang YM, Shan YQ, Han YX, et al. Host apolipoprotein B messenger RNA-editing enzyme catalytic polypeptide-like 3G is an innate defensive factor and drug target against hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2011;53:1080–1089. doi: 10.1002/hep.24160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, Ellis B, Gautier L, Ge Y, Gentry J, et al. Bioconductor: Open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carlson M. Agilent 'Human Genome, Whole' annotation data (chip hgug4112a). R package version 3.2.3. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robyr R, Boulvain M, Lewi L, Huber A, Hecher K, Deprest J, Ville Y. Cervical length as a prognostic factor for preterm delivery in twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome treated by fetoscopic laser coagulation of chorionic plate anastomoses. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;25:37–41. doi: 10.1002/uog.1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson WE, Li C, Rabinovic A. Adjusting batch effects in microarray expression data using empirical Bayes methods. Biostatistics. 2007;8:118–127. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxj037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carlson M, Falcon S, Pages H, Li N. KEGG.db: A set of annotation maps for KEGG. KEGG.db. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Draghici ALTaPKaS . SPIA: Signaling Pathway Impact Analysis (SPIA) using combined evidence of pathway over-representation and unusual signaling perturbations. 2013. (R package version 2.28.0). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tarca AL, Draghici S, Khatri P, Hassan SS, Mittal P, Kim J, Kim CJ, Kusanovic JP, Romero R. A novel signaling pathway impact analysis. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:75–82. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jelier R, Schuemie MJ, Veldhoven A, Dorssers LC, Jenster G, Kors JA. Anni 2.0: A multipurpose text-mining tool for the life sciences. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R96. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-6-r96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo W, Brouwer C. Pathview: An R/Bioconductor package for pathway-based data integration and visualization. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1830–1831. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muffak-Granero K, Bueno P, Olmedo C, Comino AM, Hassan L, Garcia-Alcalde F, Serradilla M, García-Navarro A, Mansilla A, Villar JM, et al. Study of gene expression profile in liver transplant recipients with hepatitis C virus. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:2971–2974. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi SS, Bradrick S, Qiang G, Mostafavi A, Chaturvedi G, Weinman SA, Diehl AM, Jhaveri R. Up-regulation of Hedgehog pathway is associated with cellular permissiveness for hepatitis C virus replication. Hepatology. 2011;54:1580–1590. doi: 10.1002/hep.24576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haynes WA, Higdon R, Stanberry L, Collins D, Kolker E. Differential expression analysis for pathways. PLOS Comput Biol. 2013;9:e1002967. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cacoub P, Comarmond C. New insights into HCV-related rheumatologic disorders: A review. J Adv Res. 2017;8:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petterson T, Jendholm J, Månsson A, Bjartell A, Riesbeck K, Cardell LO. Effects of NOD-like receptors in human B lymphocytes and crosstalk between NOD1/NOD2 and Toll-like receptors. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;89:177–187. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0210061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Modaresi Esfeh J, Ansari-Gilani K. Steatosis and hepatitis C. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2016;4:24–29. doi: 10.1093/gastro/gov040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Demir M, Demir C. Effect of hepatitis C virus infection on the left ventricular systolic and diastolic functions. South Med J. 2011;104:543–546. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31822462e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nam YJ, Kim SJ, Shin WC, Lee JH, Choi WC, Kim KY, Han TH. Gastric pH and Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with liver cirrhosis. Korean J Hepatol. 2004;10:216–222. In Korean. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saunders J, Cargill J, Wormsley K. Gastric secretion of acid in patients with pancreatic disease. Digestion. 1978;17:365–369. doi: 10.1159/000198129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carrière F, Grandval P, Renou C, Palomba A, Priéri F, Giallo J, Henniges F, Sander-Struckmeier S, Laugier R. Quantitative study of digestive enzyme secretion and gastrointestinal lipolysis in chronic pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:28–38. doi: 10.1016/S1542-3565(04)00601-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Masini M, Campani D, Boggi U, Menicagli M, Funel N, Pollera M, Lupi R, Del Guerra S, Bugliani M, Torri S, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection and human pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:940–941. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.4.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katakura Y, Yotsuyanagi H, Hashizume K, Okuse C, Okuse N, Nishikawa K, Suzuki M, Iino S, Itoh F. Pancreatic involvement in chronic viral hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3508–3513. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i23.3508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haffar S, Bazerbachi F, Garg S, Lake JR, Freeman ML. Frequency and prognosis of acute pancreatitis associated with acute hepatitis E: A systematic review. Pancreatology. 2015;15:321–326. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2015.05.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vaghefi M. Nucleoside Triphosphates and Their Analogs: Chemistry, Biotechnology, and Biological Applications. CRC press; London: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lan KH, Sheu ML, Hwang SJ, Yen SH, Chen SY, Wu JC, Wang YJ, Kato N, Omata M, Chang FY, et al. HCV NS5A interacts with p53 and inhibits p53-mediated apoptosis. Oncogene. 2002;21:4801–4811. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Niyogi S. Increasing antimicrobial resistance - an emerging problem in the treatment of shigellosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13:1141–1143. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baer JT, Vugia DJ, Reingold AL, Aragon T, Angulo FJ, Bradford WZ. HIV infection as a risk factor for shigellosis. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:820–823. doi: 10.3201/eid0506.990614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aragón TJ, Vugia DJ, Shallow S, Samuel MC, Reingold A, Angulo FJ, Bradford WZ. Casecontrol study of shigellosis in San Francisco: the role of sexual transmission and HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:327–334. doi: 10.1086/510593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Monaco S, Ferrari S, Gajofatto A, Zanusso G, Mariotto S. HCV-related nervous system disorders. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:236148. doi: 10.1155/2012/236148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nimnual A, Bar-Sagi D. The two hats of SOS. Sci STKE. 2002;2002:pe36. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.145.pe36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cutler RE, Jr, Stephens RM, Saracino MR, Morrison DK. Autoregulation of the Raf-1 serine/threonine kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9214–9219. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Giambartolomei S, Covone F, Levrero M, Balsano C. Sustained activation of the Raf/MEK/Erk pathway in response to EGF in stable cell lines expressing the hepatitis C virus (HCV) core protein. Oncogene. 2001;20:2606–2610. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Q, Gong R, Qu J, Zhou Y, Liu W, Chen M, Liu Y, Zhu Y, Wu J. Activation of the Ras/Raf/MEK pathway facilitates hepatitis C virus replication via attenuation of the interferon-JAK-STAT pathway. J Virol. 2012;86:1544–1554. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00688-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paul F, Pellegrini S, Uze G. IFNA2: The prototypic human alpha interferon. Gene. 2015;567:132–137. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.04.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Petta S, Bellia C, Mazzola A, Cabibi D, Cammà C, Caruso A, Di Marco V, Craxì A, Ciaccio M. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase homozygosis and low-density lipoproteins in patients with genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19:465–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Adamek A1, Kasprzak A, Mikoś H, Przybyszewska W, Seraszek-Jaros A, Czajka A, Sterzyńska K, Mozer-Lisewska I. The insulin-like growth factor-1 and expression of its binding protein3 in chronic hepatitis C and hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2013;30:1337–1345. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Long J, Wang Y, Li M, Tong WM, Jia JD, Huang J. Correlation of TP53 mutations with HCV positivity in hepatocarcinogenesis: Identification of a novel TP53 microindel in hepatocellular carcinoma with HCV infection. Oncol Rep. 2013;30:119–124. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]