Abstract

The G-protein beta subunit 3 (GNB3) gene has been implicated in obesity risk; however, the molecular mechanism of GNB3-related disease is unknown. GNB3 duplication is responsible for a syndromic form of childhood obesity, and an activating DNA sequence variant (C825T) in GNB3 is also associated with obesity. To test the hypothesis that GNB3 overexpression causes obesity, we created bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) transgenic mice that carry an extra copy of the human GNB3 risk allele. Here we show that GNB3-T/+ mice have increased adiposity, but not greater food intake or a defect in satiety. GNB3-T/+ mice have elevated fasting plasma glucose, insulin, and C-peptide, as well as glucose intolerance, indicating type 2 diabetes. Fasting plasma leptin, triglycerides, cholesterol and phospholipids are elevated, suggesting metabolic syndrome. Based on a battery of behavioral tests, GNB3-T/+ mice did not exhibit anxiety- or depressive-like phenotypes. GNB3-T/+ and wild-type animals have similar activity levels and heat production; however, GNB3-T/+ mice exhibit dysregulation of acute thermogenesis. Finally, Ucp1 expression is significantly lower in white adipose tissue (WAT) in GNB3-T/+ mice, suggestive of WAT remodeling that could lead to impaired cellular thermogenesis. Taken together, our study provides the first functional link between GNB3 and obesity, and presents insight into novel pathways that could be applied to combat obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Introduction

Obesity is a chronic disease associated with significant morbidity and mortality, affecting over 600 million adults globally [1]. Furthermore, obesity is an important risk factor for metabolic conditions such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular problems including hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and congestive heart failure, as well as certain cancers [2–4]. Obesity is a highly heritable trait–twin and adoption studies estimate that over 70% of the variance in BMI is attributed to genetic factors [5,6]. Since the identification of leptin (LEP) as the first obesity gene [7], several other Mendelian forms of non-syndromic obesity have been discovered [8–10]. Along with monogenic forms of obesity, genetic disorders like Prader-Willi and Bardet-Biedl syndromes include obesity as a significant phenotype [9]. Moreover, genome-wide association studies have identified alleles that contribute to common forms of obesity [11]. Though many genetic causes have been discovered, additional genes are necessary to explain the “missing heritability” in obesity [12,13].

We recently described a syndrome associated with obesity, seizures, and intellectual disability in individuals with an unbalanced chromosome translocation that leads to an 8.5-megabase (Mb) duplication of chromosome 12 and a 7.0-Mb deletion of chromosome 8 [14]. One of the duplicated genes on chromosome 12 is the obesity candidate gene GNB3, which encodes the G-protein β3 subunit. Specific in vivo interactions of the Gβ subunits with other Gα and Gγ subunits are unknown [15,16]. However, a silent cytosine to thymine (C825T) polymorphism in GNB3 is associated with hypertension and obesity [17]. This variant, located in exon 10 of GNB3, does not alter the amino acid sequence; however, the T-allele is associated with alternative splicing of exon 9 and encodes a splice variant (GNB3-s) with a 123-bp in-frame deletion [18]. The T-allele is also associated with increased signal transduction by activation of G-proteins in human cells [18]. GNB3-s produces a functional protein; yet, the properties of GNB3-s that enhance activation of G-proteins in unknown. Since Gβ subunits are important mediators of transmembrane signaling [19], GNB3-s could enhance signal transduction in a variety of tissues. How the GNB3-T allele, the associated splice variant, and increased G-protein signal transduction contribute to obesity risk are not understood.

Though Gnb3 knock-out does not alter body weight in mice [20], our human data suggested that GNB3 duplication leads to obesity. To model GNB3 overexpression, we created transgenic mice carrying the T variant of human GNB3 [14]. In addition to the two endogenous copies of Gnb3, GNB3-T/+ mice carry two copies of human GNB3-T. Previous work from our group demonstrated that heterozygous GNB3 transgenic mice weigh significantly more than sex- and age-matched wild-type (WT) littermates and that GNB3-T is highly expressed in the brain [14]. Here, we build upon these findings and establish that GNB3 overexpression causes increased adiposity, glucose intolerance, metabolic syndrome and dysregulation of acute thermogenesis in mice even though food intake, satiety, activity levels, energy expenditure, and behavioral phenotypes are similar to that of WT animals.

Materials and methods

Animals

Mice were housed in a 22–23°C climate controlled room on a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 0700 h), in static micro-isolator cages with free access to water and standard rodent chow (Purina LabDiet 5001). Mice rooms were in an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC)-accredited facility in accordance with the National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All animal studies were performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Emory University. The BAC transgenic GNB3-T/+ mice were developed on a FVB background as previously described [14]. Mice were weighed once a week or once every 5 weeks from weaning to 25 weeks of age. Mice were euthanized by isoflurane.

Food intake

Littermate mice were housed in groups of 2–3, separated by sex and genotype. Mice had free access to water and chow in cages that were supplied with a pre-weighed amount of food. For three days, the remaining food in the cage was weighed every 12 hours at ages 5, 10, 15, 20 and 25 weeks. Mice were acclimated to the cages for at least 24 hours before measuring food intake. Per mouse food consumption was calculated by dividing the total amount of food consumed in cage (g) by the number of animals in cage.

Tissue weights

Inguinal and gonadal WAT, brown adipose tissue (BAT) and liver were dissected and weighed. Percent tissue weights were calculated by dividing tissue weight by total body weight of each mouse. Mouse length was measured from nose to anus.

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA)

Body composition was measured using DXA scanning (Lunar PIXImus2 densitometer, GE Medical Systems) after anesthesia using isoflurane at ages 5 and 20 weeks.

Blood analysis

Five and 20-week-old mice were fasted for 6 hours. Blood glucose was measured by a glucometer (Accu-Check Aviva, Roche) from a drop of tail blood collected by milking the tail. For metabolic, lipid and hormone profiling, blood was collected by cardiac puncture following euthanasia using isoflurane. Blood collection started between 1:00 and 2:00 pm each day. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor (EMD Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA), aprotinin (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA), protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) and serine protease inhibitor (AEBSF) (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) were added to samples collected in tubes coated with EDTA (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Fasting blood plasma was separated immediately by centrifuge (1000×g) for 10 minutes at room temperature and was aliquoted and stored at −20°C. Plasma concentrations of amylin (active), C-peptide, acylated ghrelin (active), GIP (total), GLP-1 (active), glucagon, IL-6, insulin, leptin, MCP-1, PP, PYY, resistin and TNF-α were measured using MILLIPLEX MAP mouse metabolic hormone magnetic bead panel kit (MMHMAG-44K). Plasma concentrations of ACTH, FSH, GH, prolactin, TSH and LH were measured using MILLIPLEX MAP mouse pituitary magnetic bead panel kit (MPTMAG-49K) (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Plasma triglycerides, cholesterol, phospholipids and non-esterified fatty acids were measured at the Mouse Metabolic Phenotyping Center (Cincinnati, OH, USA).

Glucose tolerance test and insulin tolerance test

For the glucose tolerance test (GTT), 5 and 20-week-old mice were fasted for 6 hours and injected intraperitoneally with 1 mg/g D-glucose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). For the insulin tolerance test (ITT), 20-week-old mice were fasted for 4 hours and injected intraperitoneally with insulin (I9278 SIGMA, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) using 0.05 units/kg (females) or 0.1 units/kg (males). Blood glucose levels were measured from the tip of the tail using a glucometer (Accu-Check Aviva, Roche) at -5, 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 60, 120 min after injection for GTT, and at 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 75, 90 min after injection for ITT, respectively.

Indirect calorimetry study

Five and 20–22 week old male mice were housed individually in metabolic chambers with free access to food and water on a 12 hour light/dark cycle, and assessed for metabolic activities using an OPTO-M3 sensor system (Oxymax, Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH, USA). Spontaneous activity, volume of oxygen consumption (VO2) and volume of carbon dioxide production were measured over a 72 hour collection period after 48 hours of acclimation.

Cold challenge: Rectal temperature measurement

Rectal temperature of 5 and 20 week old mice was measured using a MicroTherma 2T hand held thermometer (ThermoWorks, Lindon, UT, USA) at time 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 75 min after placement in a 4°C room.

Behavioral tests

We used an established repertoire of tests [21] to examine anxiety- and depressive-like behaviors in adult GNB3-T/+ and WT mice. Mice were between 19–23 weeks old and behavioral tests were started between 2:00 and 3:00 pm each day. The same investigator conducted all experiments and was blinded to treatment group. Both groups were counterbalanced. Behavioral tests were conducted on subsequent days in the following order: open field testing and novelty suppressed feeding, social interaction, marble burying, novel object recognition. For all behavioral assays, 6 GNB3-T/+ and 6 WT subjects were used.

The open field test measures both general locomotor activity and anxiety-like behavior [22–24]. Mice were placed in a corner of a 45x45 cm2 square box and allowed to explore for 10 minutes. Noldus Ethovision software was used to record and analyze total distance moved, frequency of entrance into the center zone, time spent in center zone, and latency to enter center zone.

Novelty suppressed feeding measures the latency to feed in a novel environment and is sensitive to administration of anti-depressants and anxiolytics [25]. Mice were tested on the same day as the open field test to ensure animals were not habituated to the environment. Three grams of sucrose pellets were placed in the center of the open field box and mice were allowed to freely explore for 10 minutes. After testing, mice were placed back in the home cage along with the sucrose pellets and were allowed to feed for an additional 5 minutes. The sucrose pellets left over were weighed and subtracted from the initial amount to determine total amount of sucrose eaten. All mice were habituated to sucrose pellets at least 24 hours before testing.

Social interaction is also a measure of anxiety-like behavior in mice [26,27] and was assessed with age-matched, non-littermate mice as a stimulus. The stimulus mouse was placed at the center of the open field box and the reactive mouse was placed in a corner of the open field box. Mice were allowed to interact for 10 minutes. Latency to interact and total interaction time were analyzed.

The marble burying test also examines anxiety-like behavior [28]. Using clean mouse cages with twice the normal amount of bedding, twenty marbles were placed on top of bedding in a 4x5 pattern. Mice were placed in a corner of the box and allowed to explore for 30 minutes. After testing mice were removed and two researchers independently counted the number of marbles buried.

The novel object recognition task is used to assess learning and memory in mice [29,30]. Testing was conducted in the open field box over three successive days. For each round of testing, mice were placed in the same corner of the open field box. Two identical objects were placed in opposite corners of the box and mice were allowed to explore freely for 10 minutes. Mice were habituated to the test set-up for one day before testing. For the no-delay test, one of the objects was replaced by a novel object immediately after. For the one-hour and 24-hour delay tests, mice were placed back in the home cage for one or 24 hours, respectively. Mice were then placed back in the box with a different novel object and allowed to explore for 10 minutes. Noldus Ethovision software was used to record and analyze number of object touches, time spent sniffing each object, latency to approach objects, total distance moved, and average velocity.

Histology

Inguinal and gonadal WAT were fixed in 10% formalin. Tissue processing, embedding, sectioning and haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining were performed at Emory University Winship Pathology Core Lab. Adipocyte size was measured using ImageJ software [31].

Gene expression: Total RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from fresh tissue using the RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini kit (Qiagen, Austin, TX, USA) following manufacturer’s instructions and cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) mixed with gene-specific primers on the Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System. Expression data were normalized by the 2-[delta][delta]Ct method using Gapdh as an internal control. Primer sequences are listed in S1 Table. Taqman quantitative RT-PCR was performed as described [14] to measure GNB3 and Gnb3 expression using Actb as an internal control.

Protein extraction and western blot analysis

Inguinal WAT (iWAT) and BAT were dissected, weighed and immediately homogenized on ice in CelLytic MT Mammalian Tissue Lysis/Extraction Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) with protease inhibitor cocktail. Total protein concentration was determined using Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA).

Citrate synthase

Citrate synthase activity for iWAT and BAT extracts were measured using the Citrate Synthase Assay Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 6 for Mac (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Data are presented as mean ± SD (or SEM where indicated). Unpaired Student’s t-test was used to compare two groups, and one-way ANOVA was used to compare more than two groups. Comparisons with p-values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

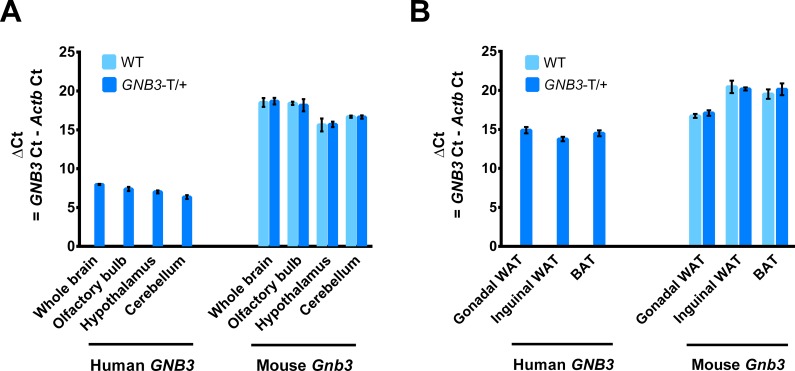

Transgenic GNB3 expression in brain and adipose tissue

In this study, we refer to mice heterozygous for the human BAC transgene as GNB3-T/+. To determine the expression levels of human GNB3 and endogenous Gnb3 we performed quantitative RT-PCR in RNA from whole brain, olfactory bulb, hypothalamus, and cerebellum of 5-week-old GNB3-T/+ and WT mice. As expected, we did not detect human GNB3 in WT mice. Notably, human GNB3 expression was much greater than endogenous Gnb3 in whole brain, olfactory bulb, hypothalamus and cerebellum of GNB3-T/+ mice as calculated by delta cycle threshold values (Fig 1A). We also detected expression of human GNB3 and endogenous Gnb3 in adipose tissue from 20-week-old GNB3-T/+ and WT mice. Human GNB3 expression was 4-fold greater than endogenous Gnb3 in gonadal WAT (gWAT), and 50-fold greater than endogenous Gnb3 in iWAT and BAT (Fig 1B).

Fig 1. Transgenic GNB3 is highly expressed in the brain, at levels greater than endogenous Gnb3.

A. Transgenic human GNB3 and mouse endogenous Gnb3 gene expression in brain tissues of 5-week-old mice. B. GNB3 and Gnb3 expression in gWAT, iWAT, and BAT of 20-week-old mice. n = 4 mice per group in A, n = 3 mice per group in B. 3 technical replicates for both. Ct, cycle threshold.

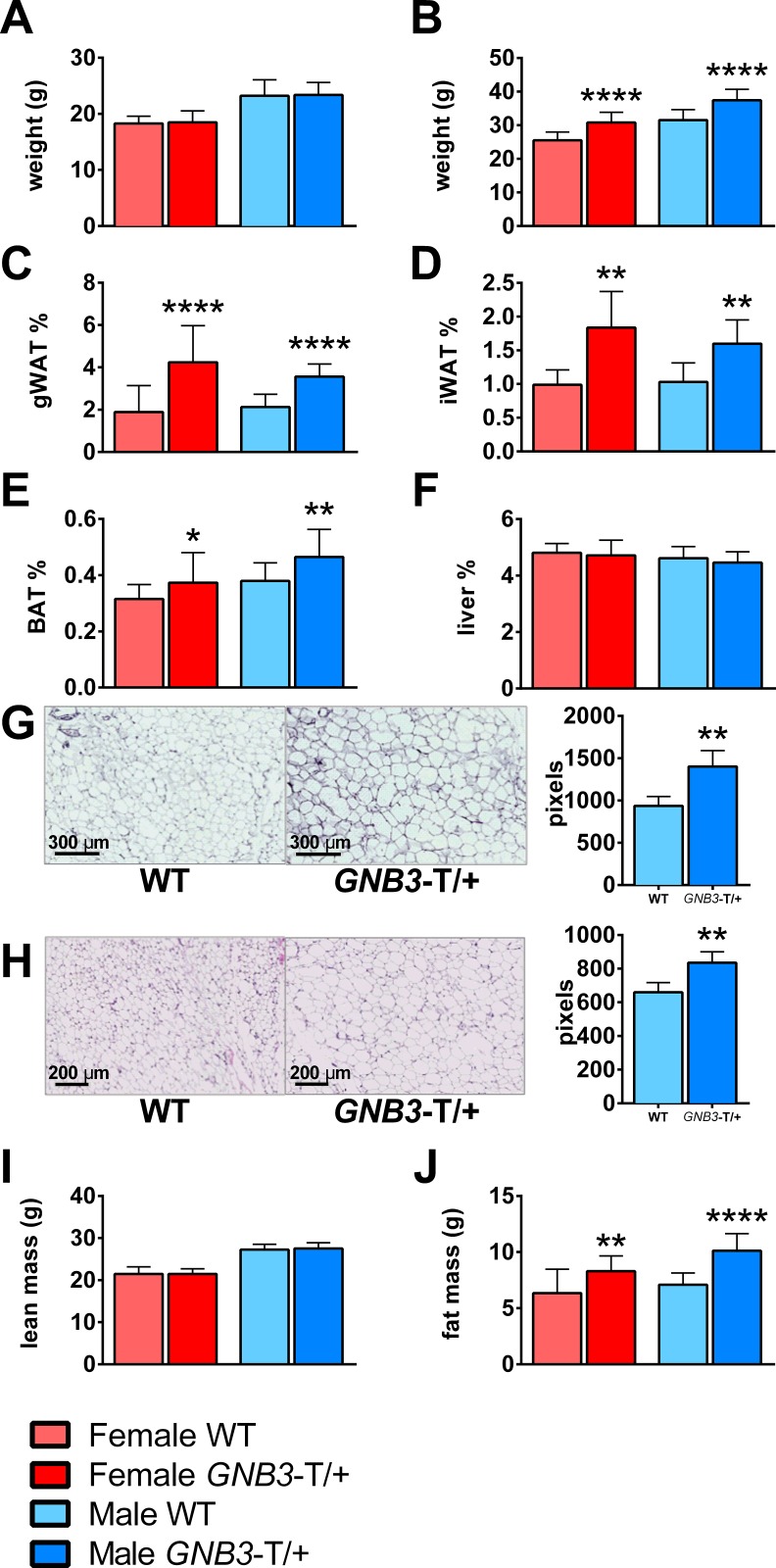

Greater adiposity in GNB3-T/+ mice

In our previous studies, we found that GNB3-T/+ mice weighed significantly more than WT littermates starting at age 6–7 weeks onwards [14]. We chose two ages, 5 weeks and 20 weeks, to evaluate the phenotypes of mice before and after obesity onset (Fig 2A and 2B) and weighed gWAT and iWAT as representative of visceral and subcutaneous WAT depots, respectively (S2 Table). At 5 weeks, GNB3-T/+ and WT mice had similar gWAT%, iWAT%, BAT%, and liver% (S1A–S1D Fig). However, at 20 weeks, female and male GNB3-T/+ mice had greater gWAT%, iWAT%, and BAT%, but similar liver% compared to WT (Fig 2C–2F). H&E staining revealed GNB3-T/+ adipocytes were 50% larger in gWAT (Fig 2G) and 27% larger in iWAT (Fig 2H) depots compared to WT. To further investigate body composition, we performed DXA on GNB3-T/+ and WT mice. Though lean mass of GNB3-T/+ and WT mice was the same at 5 and 20 weeks (Fig 2I, S1 Fig), fat mass was increased in male and female GNB3-T/+ mice at 20 weeks (Fig 2J).

Fig 2. GNB3-T/+ mice have greater adiposity than WT.

A. Body weight of 5-week-old mice. B. Body weight, C. gWAT weight/body weight (gWAT%), D. iWAT weight/body weight (iWAT%), E. BAT weight/body weight (BAT%), F. liver weight/body weight (liver%) of 20-week-old mice. G. Representative images of 20-week-old gWAT and H. iWAT sections stained with H&E; cell size measured in pixels to the right. I. DXA lean mass and J. DXA fat mass of 20-week-old mice. n = 8–11 mice per group in A; n = 16–23 mice per group in B, C and E; n = 5–9 mice per group in D; n = 10–20 mice per group in F; n = 5 mice per group in G, H (five images per mouse were used to quantify adipocyte size in pixels); n = 17–20 mice per group in I, J. Data are mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 vs. WT of same sex by unpaired Student’s t-test.

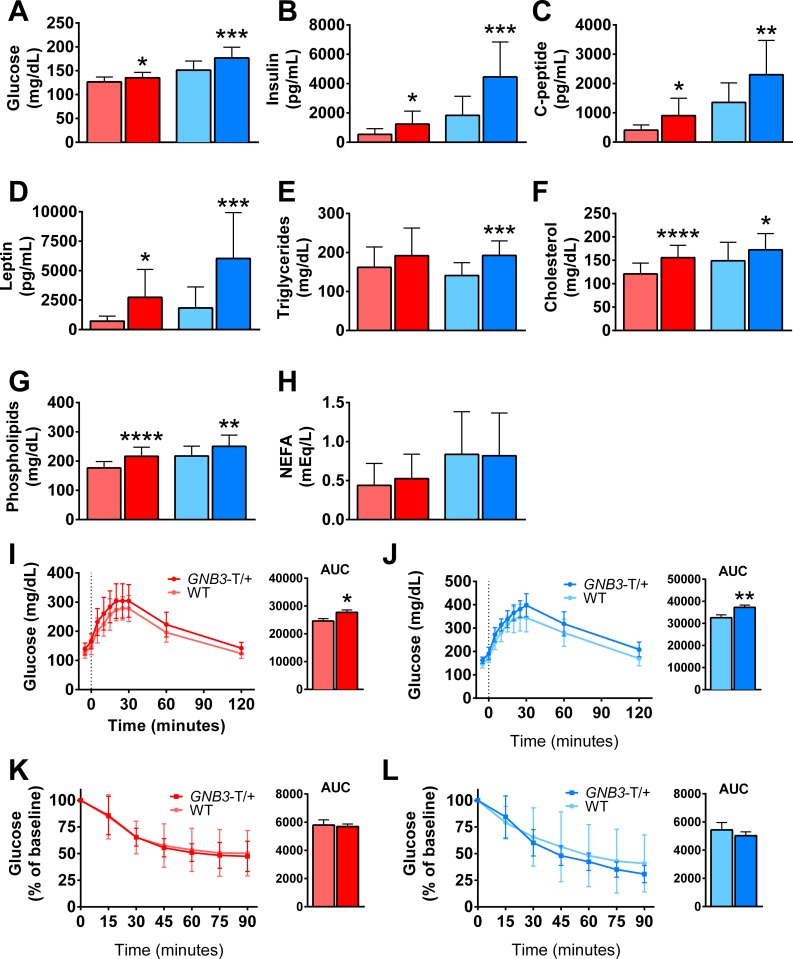

GNB3-T/+ mice have metabolic syndrome

Next, we investigated the metabolic profiles of GNB3-T/+ mice prior to and during obesity. At 20-weeks-old, female and male GNB3-T/+ mice had elevated fasting blood glucose, fasting plasma insulin, and C-peptide compared to WT (Fig 3). However, at 5 weeks, fasting blood glucose was greater only in female GNB3-T/+ mice, but female and male GNB3-T/+ mice had elevated fasting plasma insulin (S2A and S2B Fig). Lipid profiling revealed that at 5 weeks, fasting plasma leptin, triglycerides, and cholesterol were similar for GNB3-T/+ mice and WT in both sexes (S2D–S2F Fig). Phospholipids were elevated, and non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA) were lower in female GNB3-T/+ mice, while in males both were similar to WT (S2G and S2H Fig). At 20 weeks, GNB3-T/+ mice had higher fasting plasma leptin, triglycerides, cholesterol, and phospholipids; however, NEFA were similar for GNB3-T/+ mice and WT (Fig 3).

Fig 3. GNB3-T/+ mice have metabolic syndrome.

A. Fasting blood glucose, B. fasting plasma insulin, C. C-peptide, D. leptin, E. triglycerides, F. cholesterol, G. phospholipids and H. non-esterified fatty acids of mice. I. GTT and areas under the curve (AUC) of female and J. male mice. K. ITT and AUC of female and L. male mice. All mice are 20 weeks old. n = 15–23 mice per group in A, n = 11–20 mice per group in B-D, n = 16–25 mice per group in E-H, n = 18–22 mice per group in I, n = 17–18 mice per group in J, n = 14–16 mice per group in K, n = 10–17 mice per group in L. Data are mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 vs. WT of same sex by unpaired Student’s t-test. Colors are the same as in Fig 2.

To evaluate the impact of GNB3 overexpression on glucose metabolism, we subjected mice to a GTT prior to and during obesity. At 5 weeks of age, GNB3-T/+ and WT mice have similar glucose tolerance (S2I and S2J Fig). However, at 20 weeks, as indicated by glycemia levels and calculations of area under the curve (AUC), female and male GNB3-T/+ mice exhibited glucose intolerance (Fig 3I and 3J). To follow up these findings, we assessed insulin sensitivity at 20 weeks old via ITT. For both sexes, insulin sensitivity was similar between GNB3-T/+ and WT mice (Fig 3K and 3L), though fasting insulin was elevated in GNB3-T/+ mice (Fig 3B). This difference could be explained by the low insulin concentration used in the ITT, which was determined empirically.

Further metabolic profiling revealed that prior to obesity, fasting plasma glucagon, resistin and gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) were not significantly different in GNB3-T/+ and WT mice (S3A, S3C and S3E Fig). At 20 weeks of age, resistin was elevated only in male GNB3-T/+ mice, while GNB3-T/+ glucagon and GIP levels were not different than WT in either sex (S3B, S3D and S3F Fig). Inflammatory marker IL-6, TNF-alpha and MCP-1 levels in fasting plasma were similar between GNB3-T/+ and WT mice prior to and during obesity (S3G–S3L Fig). Growth hormone (GH), thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), prolactin, and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels were similar between GNB3-T/+ and WT mice at 5 weeks. However, at 20 weeks, GH, TSH, FSH, LH and prolactin were lower in obese GNB3-T/+ male mice (S4 Fig). It is important to note that GH secretion is pulsatile, so we measured GH at the same time point each day to minimize variation.

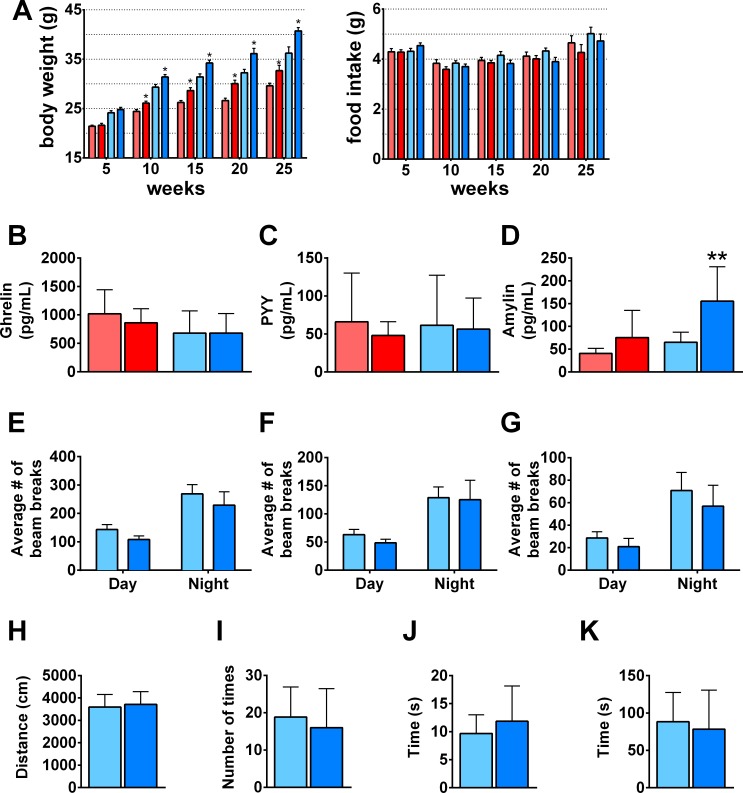

No significant difference detected between GNB3-T/+ and WT mice in food intake and activity levels

The increased adiposity and total body weight in GNB3-T/+ mice could be due to greater food intake, lack of activity, or a metabolic defect in energy expenditure. To investigate these possibilities, we measured food consumption at ages 5, 10, 15, 20 and 25 weeks (Fig 4A). At each time point, food intake was not significantly different between GNB3-T/+ and WT mice. Prior to obesity, fasting plasma ghrelin was lower, but PYY and amylin were elevated in male GNB3-T/+ mice; no difference was detected between GNB3-T/+ and WT females (S5A–S5C Fig). At 20 weeks of age, GNB3-T/+ fasting plasma ghrelin and PYY levels were similar to WT, while amylin was elevated in GNB3-T/+ mice (Fig 4), suggesting proper satiety.

Fig 4. GNB3-T/+ mice have proper satiety, similar food intake and activity levels compared to WT.

A. Daily amount of food consumption per mouse (right) and corresponding body weight of same mice (left) measured every 5 weeks for 25 weeks. B. Fasting plasma ghrelin, C. PYY, D. amylin. E. Total movement in X-plane, F. horizontal ambulatory activity, and G. vertical activity averaged over a 72-hour period. H. Distance moved, I. frequency of entrance into center zone, J. time spent in center, K. latency during open field test. Mice are 20 weeks old in B-K. n = 24–33 mice per group in A, n = 10–13 mice per group in B, n = 7–19 mice per group in C, n = 4–13 mice per group in D, n = 16–31 mice per group in E-G, n = 6–7 mice per group in H-K. Data are mean ± SD in B-D, H-K; and mean ± SEM in A, E-G. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. WT of same sex by unpaired Student’s t-test. Colors are the same as in Fig 2.

Next, we measured locomotor activity in GNB3-T/+ mice over the course of three days. Horizontal and vertical activity levels during day and night cycles were not significantly different between GNB3-T/+ and WT mice at 5 weeks (S5D–S5F Fig) or 20 weeks of age (Fig 4E–4G). In addition, there was no significant difference in total distance moved, frequency of center zone entrances, time spent in the center zone, or latency to center zone between the GNB3-T/+ and WT mice in open field testing (Fig 4H–4K). This suggests that there is not a general locomotor defect in GNB3-T/+ mice, or an anxiety-like phenotype that would affect locomotor activity.

Energy expenditure and Ucp1 expression in GNB3-T/+ mice

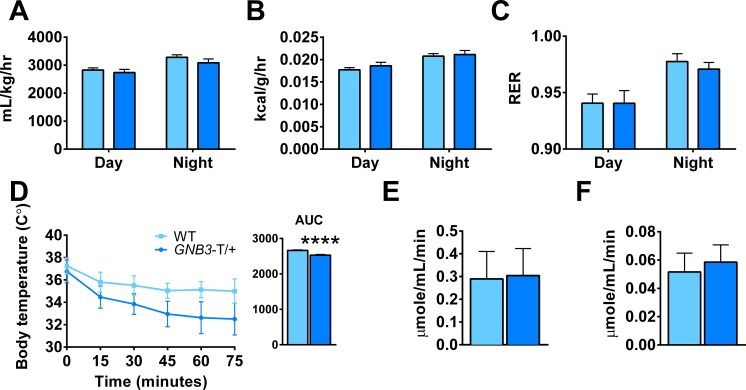

Since food intake and locomotor activity were similar between GNB3-T/+ and WT mice, we next considered energy expenditure. Using metabolic cages, we measured VO2, heat production, and respiratory exchange ratio (RER) in male mice. At 5 weeks old, VO2, heat and RER measurements are similar in GNB3-T/+ and WT mice (S6A–S6C Fig). Once obese, GNB3-T/+ mice consume less oxygen, though the difference is not statistically significant. Heat production and RER in GNB3-T/+ mice are comparable to WT (Fig 5).

Fig 5. Oxygen consumption is similar in GNB3-T/+ and WT mice, but GNB3-T/+ mice have dysregulation of acute thermogenesis.

A. VO2, B. heat produced normalized over body weight, and C. RER (VCO2/VO2) averaged over a 72-hour period. D. Acute cold stress at 4°C, E. citrate synthase activity in BAT and F. iWAT. All mice are 20 weeks old. n = 16–31 mice per group in A-C, n = 8–14 mice per group in D, n = 13–14 mice per group in E, F. Data are mean ± SEM in A-C; and mean ± SD in D-F. ****P < 0.0001 vs. WT of same sex by unpaired Student’s t-test.

To further probe differences in energy expenditure, we performed an acute cold challenge at 4°C for 75 minutes and monitored the core body temperature of mice. Prior to obesity, GNB3-T/+ and WT mice dropped their core body temperatures at a similar rate during acute cold stress (S6D Fig). However, at 20 weeks old, GNB3-T/+ mice had significantly lower core body temperature compared to WT (Fig 5D). Since failure to maintain body temperature during acute cold exposure could be related to BAT function, we measured citrate synthase, a marker of mitochondrial activity [32]. Citrate synthase activity was comparable in BAT and iWAT from 20-week-old GNB3-T/+ and WT mice (Fig 5E and 5F).

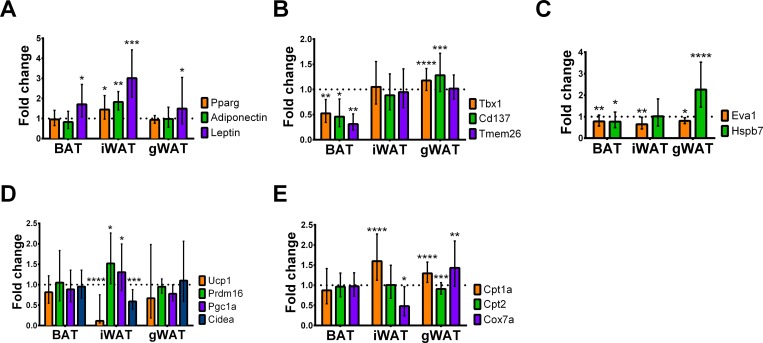

Gene expression in GNB3-T/+ mice

We measured expression of oxidative phosphorylation, mitochondria, and white, beige, and brown adipocyte markers by quantitative RT-PCR in BAT, iWAT, and gWAT, and calculated the fold change between GNB3-T/+ and WT mice. Leptin expression was increased in BAT, iWAT and gWAT. Adipogenic markers Pparg and adiponectin were elevated in iWAT (Fig 6A). Beige adipocyte markers Tbx1, Cd137, and Tmem26 (Fig 6B) as well as brown adipocyte markers Eva1 and Hspb7 had lower expression in BAT. Eva1 expression was also lower in iWAT and gWAT, while Hspb7 expression was elevated in gWAT (Fig 6C). Expression of Ucp1, a marker of brown and beige adipocytes, was lower most dramatically in iWAT. Additionally, iWAT Prdm16 and Pgc1a expression were elevated, while Cidea expression was lower (Fig 6D). Mitochondrial genes Cpt1a, Cpt2 and Cox7a were equally expressed in BAT. Cpt1a was elevated in iWAT and gWAT, while Cox7a was lower in iWAT but elevated in gWAT (Fig 6E).

Fig 6. GNB3-T/+ mice have lower gene expression of Ucp1 in BAT, iWAT and gWAT, and lower gene expression of beige and brown adipocyte markers in BAT.

A. Gene expression profiles of adipogenic, B. beige adipocyte, C. brown adipocyte, D. oxidative phosphorylation, and E. mitochondria markers in BAT, iWAT and gWAT measured by quantitative RT-PCR. Fold change is GNB3-T/+ versus WT, mean ± SD. All mice are 20 weeks old. n = 3 mice per group and experiment was repeated 3 times. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 vs. WT of same sex by unpaired Student’s t-test.

Discussion

The mechanism of GNB3-related disease is only beginning to be understood, yet G-proteins are excellent candidates for a role in obesity [33]. By transducing extracellular signals, membrane-spanning G-protein coupled receptors activate G-protein αβγ heterotrimers [34]. Activated Gα, Gβ, and Gγ subunits are critical molecules that transmit signals to intracellular signaling pathways [35]. G-protein mediated signaling, by combinations of different Gα, Gβ, and Gγ subunit isoforms, controls diverse cellular and organismal functions such as differentiation, sensation, growth, and homeostasis [33]. Mutations in some G-protein subunit genes lead to abnormal signal transduction [36,37]. For example, impaired taste sensation, defects in metabolism, and a variety of endocrine disorders are caused by mutations in different human Gα subunits [33,37,38].

In our transgenic model, GNB3 overexpression is associated with obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome that presents without hyperphagia or reduced locomotion. Specifically, we find fat accumulation in visceral and subcutaneous WAT depots as well as in BAT. The lean mass of GNB3-T/+ and WT mice is the same, indicating that the difference in weight is strictly due to fat mass. Even though livers of GNB3-T/+ mice weighed more than WT, when normalized to total body weight (liver %), this difference was not significant.

Glucose intolerance and type 2 diabetes are apparent at 20 weeks in GNB3-T/+ mice, indicated by elevated fasting plasma glucose levels and GTT response. Though GNB3-T/+ mice did not have glucose intolerance prior to obesity, 5-week old female GNB3-T/+ mice had elevated fasting blood glucose, and both female and male GNB3-T/+ mice had elevated fasting plasma insulin. This could indicate the beginning stage of impaired glucose metabolism prior to obesity. However, GNB3-T/+ mice do not respond to the ITT like other mouse models of type 2 diabetes, indicating a milder phenotype.

GH was reduced in obese GNB3-T/+ mice, consistent with lower circulating GH in obese humans [39]. Another pituitary hormone, TSH, was also reduced in obese GNB3-T/+ mice at 20 weeks. Thyroid hormones control multiple physiological systems and have an important role in regulating basal metabolic rate, lipolysis, as well as the differentiation process in the adipose tissue [40]. FSH, LH and prolactin are reduced in obese male GNB3-T/+ mice at 20 weeks, which could indicate hypogonadotropic hypogonadism [41].

Obesity is caused by an energy imbalance between calories consumed and calories expended. The increased adiposity in GNB3-T/+ mice could be due to increased calorie intake, reduced activity, or a defect in metabolism that results in lower energy expenditure. Our results from food intake measurements and levels of fasting ghrelin, PYY, and amylin hormones revealed that hyperphagia or a satiety defect are not responsible. Novelty suppressed feeding tests also show no significant difference in the amount of sucrose eaten, latency to feed, or total feeding time between the GNB3-T/+ and WT mice, indicating that anxiety-like feeding behaviors are not involved in GNB3-related obesity. GNB3-T/+ and WT mice do not have a statistically significant difference in locomotor activity or oxygen consumption. However, it is possible that subtle differences in locomotion and/or oxygen consumption could contribute to increased adiposity. Future energy expenditure experiments conducted at thermoneutrality and/or brown fat induction experiments could shed light on the effects of GNB3 overexpression. Further, behavioral assessments indicate that there are no substantial anxiety- or depressive-like phenotypes in GNB3-T/+ mice, and that these affective phenotypes are unlikely to add to the relationship between GNB3 overexpression and obesity.

Ucp1 expression in adipose tissues provides a clue to the underlying defect in GNB3-T/+ mice. Ucp1 in mitochondria dissipates chemical energy in the form of heat, mainly in BAT, through a process called nonshivering thermogenesis [42]. Recently, BAT has become a therapeutic target in obesity and metabolic disorders. Ucp1-ablated mice are obese and have type 2 diabetes, though this only occurs when living at thermoneutrality [43]. In addition to classic brown fat, white fat depots contain UCP1+ cells [44–48] known as beige [49] or brown-white (brite) adipocytes [50]. Beige cells and classic brown adipocytes have distinctly different molecular signatures [49] and developmental origins [51]. Adult humans have UCP1+ adipose tissue which has a gene expression pattern more similar to beige cells than to classic brown cells in the mouse [49]. Though GNB3 overexpression alters the gene expression profiles of both BAT and WAT, GNB3 appears to have the greatest effect in beige-cell containing iWAT.

BAT in GNB3-T/+ mice has lower expression of beige and brown adipocyte markers. Additionally, GNB3-T/+ mice showed markedly worsened beige adipocyte function in subcutaneous fat pads as indicated by lower levels of Ucp1 in iWAT. Subcutaneous adipose tissue in GNB3-T/+ mice acquired properties of visceral fat indicated by elevated expression of adipogenic markers, Pparg and adiponectin. Overall, GNB3 overexpression stimulates a conversion of subcutaneous WAT, particularly in the inguinal depot, into a less UCP1+ and a less beige but whiter tissue. We show that this white-like remodeling of iWAT and loss of brown and beige properties in BAT is accompanied by increased adiposity in mice fed normal chow. Together, these data implicate GNB3 overexpression in impaired WAT and BAT, and for the first time provide a functional link between GNB3 and obesity pathogenesis. However, the specific causes of GNB3-related obesity remain to be determined. Future studies of GNB3 overexpression are needed to dissect the molecular mechanisms by which GNB3 alters adipose tissue metabolism, signaling, and energy expenditure.

Supporting information

A. gWAT weight/body weight (gWAT%), B. iWAT weight/body weight (iWAT%), C. BAT weight/body weight (BAT%), D. liver weight/body weight (liver%), E. DXA lean mass and F. DXA fat mass of 5-week-old mice. n = 8–11 mice per group in A, C, and D; n = 1–8 mice per group in B; n = 14–22 mice per group in E, F. Data are ± SD. No significant difference between GNB3-T/+ and WT of same sex by unpaired Student’s t-test.

(TIF)

A. Fasting blood glucose, B. fasting plasma insulin, C. C-peptide, D. leptin, E. triglycerides, F. cholesterol, G. phospholipids and H. non-esterified fatty acids. I. GTT and AUC of female and J. male mice. All mice are 5 weeks old. n = 8–11 mice per group in A, n = 7 mice per group in B-D, n = 9–13 mice per group in E-H, n = 10–14 mice per group in I, n = 11–15 mice per group in J. Data are ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. WT of same sex by unpaired Student’s t-test.

(TIF)

Male GNB3-T/+ mice have elevated fasting plasma resistin during obesity. A,B. Fasting plasma glucagon; C,D. resistin; E,F. GIP; G,H. IL-6; I.J., TNF-a; and K,L. MCP-1 in 5-week and 20-week-old mice, respectively. n = 7 mice per group in A, C, E, G, I, K; n = 10–13 mice per group in B, n = 11–20 mice per group in D, F, H, J, L. Data are ± SD. *P < 0.05 vs. WT of same sex by unpaired Student’s t-test.

(TIF)

GNB3-T/+ male mice have lower GH, TSH, FSH, LH and prolactin during obesity. A,B. Fasting plasma growth hormone (GH); C,D. thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH); E,F. follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH); G,H. luteinizing hormone (LH); I,J. prolactin; K,L. adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels of 5 week and 20 week old mice, respectively. n = 7 mice per group in A, C, E, G, I, K; n = 11–20 mice per group in B, D, F, H, J, L. Data are ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. WT of same sex by unpaired Student’s t-test.

(TIF)

A. Fasting plasma ghrelin, B. PYY and C. amylin. D. Total movement in X-plane, E. horizontal ambulatory activity, and F. vertical activity averaged over a 72-hour period. All mice are 5 weeks old. n = 7 mice per group in A-C, n = 19–21 mice per group in D-F. Data are ± SD in A-C, and ± SEM in D-F. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. WT of same sex by unpaired Student’s t-test.

(TIF)

A. VO2, B. heat produced normalized over body weight, and C. RER (VCO2/VO2) averaged over a 72-hour period. D. Acute cold stress at 4°C. All mice are 5 weeks old. n = 19–21 mice per group in A-C, n = 5–8 mice per group in D. Data are ± SEM in A-C; and ± SD in D-F. ****P < 0.0001 vs. WT of same sex by unpaired Student’s t-test.

(TIF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

GNB3-T/+ mice and WT littermates were subjected to behavioral tests in order to evaluate anxiety/depressive-like behaviors and learning and memory.

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

Some experiments were conducted with the Emory Integrated Genomics Core (EIGC), which is subsidized by the Emory University School of Medicine and is one of the Emory Integrated Core Facilities.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work received support from the Emory Discovery Fund, an internal grant from the Department of Human Genetics at Emory University.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight fact sheet. [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2016 Oct 19]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/

- 2.Chan JM, Rimm EB, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. Obesity, fat distribution, and weight gain as risk factors for clinical diabetes in men. Diabetes Care. 1994. September;17(9):961–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haslam DW, James WPT. Obesity. Lancet. 2005. October 1;366(9492):1197–209. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67483-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Rahilly S. Human genetics illuminates the paths to metabolic disease. Nature. Nature Publishing Group; 2009. November 19;462(7271):307–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stunkard AJ, Sørensen TI, Hanis C, Teasdale TW, Chakraborty R, Schull WJ, et al. An adoption study of human obesity. N Engl J Med. 1986. January 23;314(4):193–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198601233140401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stunkard AJ, Harris JR, Pedersen NL, McClearn GE. The body-mass index of twins who have been reared apart. N Engl J Med. 1990. May 24;322(21):1483–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199005243222102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature. 1994. December 1;372(6505):425–32. doi: 10.1038/372425a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blakemore AIF, Froguel P. Investigation of Mendelian forms of obesity holds out the prospect of personalized medicine. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010. December;1214:180–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05880.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabin M a, Werther G a, Kiess W. Genetics of obesity and overgrowth syndromes. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. Elsevier Ltd; 2011. February;25(1):207–20. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crowley VEF. Overview of human obesity and central mechanisms regulating energy homeostasis. Ann Clin Biochem. 2008. May;45(Pt 3):245–55. doi: 10.1258/acb.2007.007193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choquet H, Meyre D. Molecular basis of obesity: current status and future prospects. Curr Genomics. 2011. May;12(3):154–68. doi: 10.2174/138920211795677921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choquet H, Meyre D. Genetics of Obesity: What have we Learned? Curr Genomics. 2011. May;12(3):169–79. doi: 10.2174/138920211795677895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xia Q, Grant SF a. The genetics of human obesity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013. January 29;1281:178–90. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldlust IS, Hermetz KE, Catalano LM, Barfield RT, Cozad R, Wynn G, et al. Mouse model implicates GNB3 duplication in a childhood obesity syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013. September 10;110(37):14990–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305999110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krumins AM, Gilman AG. Targeted knockdown of G protein subunits selectively prevents receptor-mediated modulation of effectors and reveals complex changes in non-targeted signaling proteins. J Biol Chem. 2006. April 14;281(15):10250–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511551200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poon LSW, Chan ASL, Wong YH. Gbeta3 forms distinct dimers with specific Ggamma subunits and preferentially activates the beta3 isoform of phospholipase C. Cell Signal. 2009. May;21(5):737–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klenke S, Kussmann M, Siffert W. The GNB3 C825T polymorphism as a pharmacogenetic marker in the treatment of hypertension, obesity, and depression. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2011. September;21(9):594–606. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3283491153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siffert W, Rosskopf D, Siffert G, Busch S, Moritz A, Erbel R, et al. Association of a human G-protein beta3 subunit variant with hypertension. Nat Genet. 1998. January;18(1):45–8. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ford CE, Skiba NP, Bae H, Daaka Y, Reuveny E, Shekter LR, et al. Molecular basis for interactions of G protein betagamma subunits with effectors. Science. 1998. May 22;280(5367):1271–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ye Y, Sun Z, Guo A, Song L-S, Grobe JL, Chen S. Ablation of the GNB3 gene in mice does not affect body weight, metabolism or blood pressure, but causes bradycardia. Cell Signal. 2014. November;26(11):2514–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.07.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burgado J, Harrell CS, Eacret D, Reddy R, Barnum CJ, Tansey MG, et al. Two weeks of predatory stress induces anxiety-like behavior with co-morbid depressive-like behavior in adult male mice. Behav Brain Res. 2014. December 15;275:120–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.08.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prut L, Belzung C. The open field as a paradigm to measure the effects of drugs on anxiety-like behaviors: a review. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003. February 28;463(1–3):3–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carola V, D’Olimpio F, Brunamonti E, Mangia F, Renzi P. Evaluation of the elevated plus-maze and open-field tests for the assessment of anxiety-related behaviour in inbred mice. Behav Brain Res. 2002. August 21;134(1–2):49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choleris E, Thomas AW, Kavaliers M, Prato FS. A detailed ethological analysis of the mouse open field test: effects of diazepam, chlordiazepoxide and an extremely low frequency pulsed magnetic field. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2001. May;25(3):235–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fukumoto K, Iijima M, Chaki S. Serotonin-1A receptor stimulation mediates effects of a metabotropic glutamate 2/3 receptor antagonist, 2S-2-amino-2-(1S,2S-2-carboxycycloprop-1-yl)-3-(xanth-9-yl)propanoic acid (LY341495), and an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist, ketamine, in the. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2014. June;231(11):2291–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.File SE. The use of social interaction as a method for detecting anxiolytic activity of chlordiazepoxide-like drugs. J Neurosci Methods. 1980. June;2(3):219–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.File SE, Seth P. A review of 25 years of the social interaction test. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003. February 28;463(1–3):35–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Njung’e K, Handley SL. Evaluation of marble-burying behavior as a model of anxiety. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991. January;38(1):63–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang YP, Shimizu E, Dube GR, Rampon C, Kerchner GA, Zhuo M, et al. Genetic enhancement of learning and memory in mice. Nature. 1999. September 2;401(6748):63–9. doi: 10.1038/43432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sargolini F, Roullet P, Oliverio A, Mele A. Effects of intra-accumbens focal administrations of glutamate antagonists on object recognition memory in mice. Behav Brain Res. 2003. January 22;138(2):153–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. U. S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA; 2012. July;9(7):671–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rong JX, Qiu Y, Hansen MK, Zhu L, Zhang V, Xie M, et al. Adipose mitochondrial biogenesis is suppressed in db/db and high-fat diet-fed mice and improved by rosiglitazone. Diabetes. 2007. July;56(7):1751–60. doi: 10.2337/db06-1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wettschureck N, Offermanns S. Mammalian G proteins and their cell type specific functions. Physiol Rev. 2005. October;85(4):1159–204. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00003.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bourne HR. How receptors talk to trimeric G proteins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997. April;9(2):134–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neves SR, Ram PT, Iyengar R. G protein pathways. Science. 2002. May 31;296(5573):1636–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1071550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Offermanns S, Simon MI. Genetic analysis of mammalian G-protein signalling. Oncogene. 1998. September 17;17(11 Reviews):1375–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lania a, Mantovani G, Spada A. G protein mutations in endocrine diseases. Eur J Endocrinol. 2001. November;145(5):543–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moxham CM, Malbon CC. Insulin action impaired by deficiency of the G-protein subunit G ialpha2. Nature. 1996. February 29;379(6568):840–4. doi: 10.1038/379840a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scacchi M, Pincelli a I, Cavagnini F. Growth hormone in obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999. March;23(3):260–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Obregon M-J. Adipose tissues and thyroid hormones. Front Physiol. 2014;5:479 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teerds KJ, de Rooij DG, Keijer J. Functional relationship between obesity and male reproduction: from humans to animal models. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17(5):667–83. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol Rev. 2004. January;84(1):277–359. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feldmann HM, Golozoubova V, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. UCP1 ablation induces obesity and abolishes diet-induced thermogenesis in mice exempt from thermal stress by living at thermoneutrality. Cell Metab. 2009. February;9(2):203–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cousin B, Cinti S, Morroni M, Raimbault S, Ricquier D, Pénicaud L, et al. Occurrence of brown adipocytes in rat white adipose tissue: molecular and morphological characterization. J Cell Sci. 1992. December;103 (Pt 4:931–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ghorbani M, Himms-Hagen J. Appearance of brown adipocytes in white adipose tissue during CL 316,243-induced reversal of obesity and diabetes in Zucker fa/fa rats. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997. June;21(6):465–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guerra C, Koza RA, Yamashita H, Walsh K, Kozak LP. Emergence of brown adipocytes in white fat in mice is under genetic control. Effects on body weight and adiposity. J Clin Invest. 1998. July 15;102(2):412–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI3155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Himms-Hagen J, Melnyk A, Zingaretti MC, Ceresi E, Barbatelli G, Cinti S. Multilocular fat cells in WAT of CL-316243-treated rats derive directly from white adipocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000. September;279(3):C670–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xue B, Coulter A, Rim JS, Koza RA, Kozak LP. Transcriptional synergy and the regulation of Ucp1 during brown adipocyte induction in white fat depots. Mol Cell Biol. 2005. September;25(18):8311–22. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.18.8311-8322.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu J, Boström P, Sparks LM, Ye L, Choi JH, Giang A-H, et al. Beige adipocytes are a distinct type of thermogenic fat cell in mouse and human. Cell. 2012. July 20;150(2):366–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Petrovic N, Walden TB, Shabalina IG, Timmons JA, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Chronic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) activation of epididymally derived white adipocyte cultures reveals a population of thermogenically competent, UCP1-containing adipocytes molecularly distinct from classic brown adipocyt. J Biol Chem. 2010. March 5;285(10):7153–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.053942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seale P, Bjork B, Yang W, Kajimura S, Chin S, Kuang S, et al. PRDM16 controls a brown fat/skeletal muscle switch. Nature. 2008. August 21;454(7207):961–7. doi: 10.1038/nature07182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A. gWAT weight/body weight (gWAT%), B. iWAT weight/body weight (iWAT%), C. BAT weight/body weight (BAT%), D. liver weight/body weight (liver%), E. DXA lean mass and F. DXA fat mass of 5-week-old mice. n = 8–11 mice per group in A, C, and D; n = 1–8 mice per group in B; n = 14–22 mice per group in E, F. Data are ± SD. No significant difference between GNB3-T/+ and WT of same sex by unpaired Student’s t-test.

(TIF)

A. Fasting blood glucose, B. fasting plasma insulin, C. C-peptide, D. leptin, E. triglycerides, F. cholesterol, G. phospholipids and H. non-esterified fatty acids. I. GTT and AUC of female and J. male mice. All mice are 5 weeks old. n = 8–11 mice per group in A, n = 7 mice per group in B-D, n = 9–13 mice per group in E-H, n = 10–14 mice per group in I, n = 11–15 mice per group in J. Data are ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. WT of same sex by unpaired Student’s t-test.

(TIF)

Male GNB3-T/+ mice have elevated fasting plasma resistin during obesity. A,B. Fasting plasma glucagon; C,D. resistin; E,F. GIP; G,H. IL-6; I.J., TNF-a; and K,L. MCP-1 in 5-week and 20-week-old mice, respectively. n = 7 mice per group in A, C, E, G, I, K; n = 10–13 mice per group in B, n = 11–20 mice per group in D, F, H, J, L. Data are ± SD. *P < 0.05 vs. WT of same sex by unpaired Student’s t-test.

(TIF)

GNB3-T/+ male mice have lower GH, TSH, FSH, LH and prolactin during obesity. A,B. Fasting plasma growth hormone (GH); C,D. thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH); E,F. follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH); G,H. luteinizing hormone (LH); I,J. prolactin; K,L. adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels of 5 week and 20 week old mice, respectively. n = 7 mice per group in A, C, E, G, I, K; n = 11–20 mice per group in B, D, F, H, J, L. Data are ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. WT of same sex by unpaired Student’s t-test.

(TIF)

A. Fasting plasma ghrelin, B. PYY and C. amylin. D. Total movement in X-plane, E. horizontal ambulatory activity, and F. vertical activity averaged over a 72-hour period. All mice are 5 weeks old. n = 7 mice per group in A-C, n = 19–21 mice per group in D-F. Data are ± SD in A-C, and ± SEM in D-F. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. WT of same sex by unpaired Student’s t-test.

(TIF)

A. VO2, B. heat produced normalized over body weight, and C. RER (VCO2/VO2) averaged over a 72-hour period. D. Acute cold stress at 4°C. All mice are 5 weeks old. n = 19–21 mice per group in A-C, n = 5–8 mice per group in D. Data are ± SEM in A-C; and ± SD in D-F. ****P < 0.0001 vs. WT of same sex by unpaired Student’s t-test.

(TIF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

GNB3-T/+ mice and WT littermates were subjected to behavioral tests in order to evaluate anxiety/depressive-like behaviors and learning and memory.

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.