Abstract

Background

Algorithms for the diagnosis, management, and follow-up have been proposed for patients hospitalized for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) colitis flare. The degree to which providers adhere to these algorithms is unknown. This study evaluated the quality of care in IBD patients hospitalized for disease-associated exacerbations and factors correlated with higher degrees of care.

Methods

Retrospective chart review of 34 patients during 60 admissions to the medicine service for IBD colitis exacerbation between 2005 and 2012 at the Veterans Affairs San Diego Medical Center. Examined factors included laboratory testing, timing of consultation and intravenous steroids, abdominal imaging, endoscopic examination, venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis, narcotic use, Clostridium difficile and cytomegalovirus testing, symptomatology at discharge, timing of follow-up, and rates of readmission and mortality.

Results

Quality of care varied among the factors studied, ranging from 30.5 % for pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis to 84.7 % for gastroenterology consultation within 24 h. Of 60 admissions, 22 % were not tested for C. difficile. Fifteen percent of patients were discharged before meeting commonly used discharge criteria. Eighty percent were seen in clinic at any time post-discharge; 6.7 % were readmitted; 10 % were lost to follow-up; 1.7 % opted for outside follow-up; and 1.7 % expired.

Conclusions

The quality of care for patients admitted with IBD colitis flares is variable. These data outline opportunities for improvement, particularly in regard to pain management, VTE prophylaxis, and follow-up. Further studies are needed to test intervention strategies for practice improvement.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, Quality indicators, Crohn's disease, Ulcerative colitis

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) encompasses a complex group of inflammatory conditions, including ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Ulcerative colitis (UC) is the most widespread type of inflammatory bowel disease in the world [1]. In the USA, its prevalence effects over 200 persons per 100,000 adults [1, 2]. About 3–6 % of these patients are hospitalized annually for ulcerative colitis-related causes [3], accounting for half of the annual $3.4–8.6 billion direct healthcare cost of this disease in the USA [4, 5]. Although Crohn's disease is less prevalent than UC in the USA (affecting about 50 individuals per 100,000 people), estimated costs of medical and surgical care reach up to $2 billion per year [6]. Despite improvements in medications and a shift toward outpatient management of IBD in the past two decades, hospitalization rates have remained quite stable [7, 8].

Algorithms regarding diagnostic testing, disease and pain management, as well as timing of endoscopy and follow-up have been proposed to care for patients admitted to the hospital for inflammatory bowel disease colitis exacerbation [9, 10]. These principles include obtaining a thorough historyand physical,laboratory studies with erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein, and assays for Clostridium difficile and/or cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections. Patients should have endoscopy within 48 h of admission, and the first-line treatment is intravenous corticosteroids. Pain should be managed, but narcotics should be avoided because they are associated with higher rates of infection and mortality in outpatients and could theoretically precipitate toxic megacolon. Additionally, IBD is considered a hypercoagulable state, and all patients should receive venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis despite active disease with bloody bowel movements [6, 9, 10]. Diagnosis and treatment of Crohn's colitis in the hospital is quite similar to that of UC [6, 11]. In addition, careful discharge planning and arrangements for appropriate post-discharge follow-up appointments are important factors in preventing unnecessary readmissions [12].

The degree to which providers adhere to these treatment algorithms is unknown. A recent Australian audit of 26 patients admitted with acute severe colitis at a major metropolitan teaching hospital during a 2-year period demonstrated that management could be easily improved, including more formal assessments, endoscopic examinations, and ruling out infections [13]. A similar study in the USA has not been performed.

This study was performed to evaluate the quality of care in IBD patients admitted to the hospital for disease-associated exacerbations by analyzing adherence to proposed algorithms. Optimizing inpatient treatment of IBD and follow-up could prevent disease progression and reduce rates of readmission, as well as improve the ability of providers to deliver more medically and cost-effective care.

Methods

An Institutional Review Board-approved retrospective chart audit of IBD patients admitted to the general medicine service at the San Diego VA Healthcare System for colitis during an 8-year period (January 2005–December 2012) was performed. The San Diego VA Healthcare System is a teaching hospital affiliated with the University of California, San Diego, and has 296 authorized beds.

Cases were identified by an electronic search of all hospital discharges in the VA San Diego Medical Center electronic medical record with at least one International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis code for non-infectious colitis (ICD-9-CM 558.9), ulcerative colitis (ICD-9-CM 556.x), or Crohn's disease (ICD-9-CM 555.x). Discharge summaries were reviewed to ensure the cause of admission was IBD colitis. Patients admitted for other indications were excluded. Patients admitted to the surgical service and those treated solely for small bowel obstruction were also excluded.

Data were abstracted from the patient medical records by reviewing admission history and physicals, daily progress notes, laboratory results, radiology reports, and discharge summaries. Baseline demographics included age, race, gender, smoking status, comorbidities, and length of IBD diagnosis. Length of hospitalization was also recorded. Additionally, indications for other hospital admissions between 2005 and 2012 were noted.

Provider adherence to the following components of IBD colitis treatment was determined:

|

Within the next full day of hospital admission

Receiving IV or subcutaneous heparin or enoxaparin

These components of care were described in a care algorithm detailed by Pola et al. [9], evidence-based guidelines for managing patients hospitalized for UC [1, 10], and recommendations for post-hospital discharge care [12]. Several of the recommended assessments are important in evaluating the severity of UC and Crohn's disease, as defined by the Truelove and Witts Index [14, 15] and the Harvey–Bradshaw Index [16], respectively. The importance of reassessing symptoms and certain laboratory parameters on day 3 lies in prediction scores that help evaluate the likelihood of failing corticosteroids [17]. We consider a gastroenterology service consult important because specialist care has been shown to improve outcomes in management of specialty-related conditions [3, 18, 19].

Rates of Adherence

From the medical record data, we calculated the rate of adherence to each component of care as the percentage of admissions in which the recommended care was received among those who were eligible for that particular component of care. If one subject was admitted multiple times, each hospitalization was counted as a separate event to evaluate the rate of adherence to quality of care in each hospitalization.

Timing of Follow-Up

We examined the timing of follow-up, rates of readmission, and rates of mortality.

Predictors of Quality Care

We studied the association of clinical factors with receiving over 75 % of the components for which each patient was eligible. The independent variables considered were hemoglobin <10 g/dl, leukocytosis >12 k, and if the number of bowel movements is >10/day. We report our results as odds ratios (odds of receiving over 75 % of the components for which a patient is eligible) with 95 % confidence intervals.

Readmission

In a secondary analysis, we examined the association between adherence to the 18 quality care components listed above during each subject's index admission and subsequent readmission within 12 months. We also examined the association between follow-up within 2 weeks of index admission and subsequent readmission within 12 months. This analysis excluded the one patient who was not native to San Diego. For patients with multiple admissions, we selected the first hospitalization as the index event.

Results

Patient Population

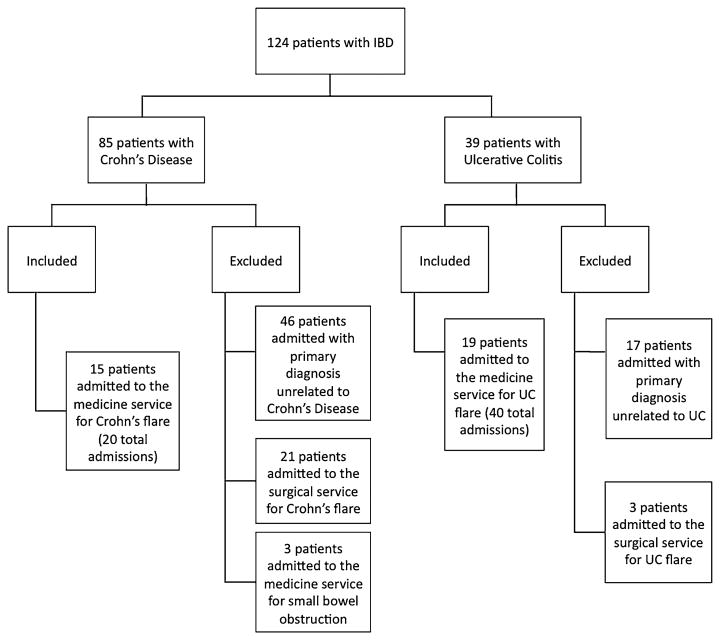

A search of all discharges within 2005–2012 in the VA database with at least one ICD-9 code for non-infectious colitis, UC, or Crohn's disease resulted in 257 admissions from 124 total patients (Fig. 1). Eighty-five of these patients had Crohn's disease. The study ultimately included the 15 patients (20 admissions) with Crohn's disease and 19 patients (40 admissions) with UC who were hospitalized on the medicine service for IBD-related exacerbations.

Fig. 1. Patient inclusion diagram.

The number of hospitalizations for patients included in this study for causes other than IBD was analyzed during the 2005–2012 time period. The 15 patients with Crohn's disease had a total of 50 hospitalizations, and the 19 UC patients had a total of 85 hospitalizations (Table 1). Of these admissions, 35.5 % were related to non-IBD conditions.

Table 1. Indications for all admissions 2005 to 2012 in the patients included in this study.

| Indication for admission, n (%) | Crohn's disease (15 patients, 50 admissions) | Ulcerative colitis (19 patients, 85 admissions) |

|---|---|---|

| Disease flare | 20 (40.0) | 40 (47.0) |

| IBD-related surgery or other IBD surgical indication | 3 (6) | 23 (27.0) |

| Bowel obstruction | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) |

| Infection | 4 (8) | 8 (9.4) |

| Psychiatric condition | 4 (8) | 2 (2.4) |

| Othera | 19 (38.0) | 11 (12.9) |

Other indications included: scheduled renal biopsy, shortness of breath, gastrointestinal bleeding due to gastric ulcer, non-IBD-related surgery (e.g., orthopedic surgery, hernia repair), tachycardia, generalized malaise, deep venous thrombosis, failure to thrive, coronary artery disease, pancreatitis

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Thirty-four patients (three female) had 60 colitis admissions under the general medicine service (Table 2). Seven of these patients were diagnosed within 0–6 months at the time of index admission; two had been diagnosed within 6–12 months; 9 had carried the diagnosis for 1–5 years; 6 had carried the diagnosis for 5–10 years; and 10 had carried the diagnosis for over 10 years. Mean age was 47.7 years >standard deviation (SD) 16.4 years]. 73.5 % were white, 17.6 % were African American, and 8.8 % were of unknown race. 55.9 % were non-smokers; 29.4 % were former smokers; and 26.5 % were current smokers. The average hemoglobin on admission was 12.1 g/dl (min 7.5, max 16.7), and the average white blood cell count was 9.7 k (min 0, max 21.8). The average admission ESR in the 36 admissions in which it was obtained was 43.1 mm/h (min 8, max 102, n = 36). The average stool frequency was 12.3 stools/day (min 2, max 50).

Table 2. Demographics of patients included in the study.

| Characteristic | Crohn's disease (15 patients with 20 total admissions) | Ulcerative colitis (19 patients with 40 total admissions) | Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis combined (34 patients with 60 total admissions) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at index admission, mean (SD) | 46.8 (16.8) | 51.9 (18.0) | 49.7 (17.4) |

| Age at admission (including all admissions), mean (SD) | 46.7 (15.8) | 48.2 (16.9) | 47.7 (16.4) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 14 (93.3) | 17 (89.5) | 31 (91.2) |

| Female | 1 (0.7) | 2 (10.5) | 3 (8.8) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 14 (93.3) | 11 (57.9) | 25 (73.5) |

| African American | 0 (0.0) | 6 (31.6) | 6 (17.6) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.7) | 2 (10.5) | 3 (8.8) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Hispanic | 1 (0.7) | 5 (26.3) | 6 (17.6) |

| Not Hispanic | 13 (86.7) | 14 (73.7) | 27 (79.4) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) |

| Admission laboratories, mean (SD; min, max) | |||

| Hgb (g/dl) | 13.0 (2.6) | 11.7 (2.3; 7.5, 15.4) | 12.1 (2.5; 7.5, 16.7) |

| Wbc (k) | 9.5 (4.4) | 9.7 (4.5; 0, 21.8) | 9.7 (4.4; 0, 21.8) |

| ESR (mm/h) | 36.2 (24.1) | 46.5 (29.2; 12, 102) | 43.1 (27.7; 8, 102) |

| Stool frequency on admission, mean (SD; min, max) | 9.0 (4.7; 2, 15) | 13.6 (10; 5, 50) | 12.3 (9.1; 2, 50) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Diabetes | 2 (13.3) | 4 (21.0) | 6 (17.6) |

| BMI > 25 | 9 (0.6) | 11 (57.9) | 20 (58.8) |

| Hypertension | 4 (26.7) | 7 (36.9) | 11 (32.4) |

| CKD | 2 (13.3) | 1 (5.3) | 3 (8.8) |

| CHF | 3 (20.0) | 2 (10.5) | 5 (14.7) |

| Depression | 6 (40.0) | 3 (15.8) | 9 (26.5) |

| Smoking history, n (%) | |||

| Never smoker | 5 (33.3) | 9 (47.4) | 14 (41.2) |

| Former smoker | 4 (26.7) | 6 (31.6) | 10 (29.4) |

| Current smoker | 5 (33.3) | 4 (21.0) | 9 (26.5) |

| Unknown | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) |

| Duration of IBD diagnosis at time of admission (including all admissions), n (%) | |||

| New–6 months | 1 (5.0) | 9 (22.5) | 10 (16.7) |

| 6 months–1 year | 2 (10.0) | 6 (15.0) | 8 (13.3) |

| 1–5 years | 5 (25.0) | 8 (20.0) | 13 (21.7) |

| 5–10 years | 7 (35.0) | 8 (20.0) | 15 (25.0) |

| Over 10 years | 5 (25.0) | 9 (22.5) | 14 (23.3) |

| Duration of IBD diagnosis at time of index admission, n (%) | |||

| New–6 months | 1 (6.7) | 6 (31.6) | 7 (20.6) |

| 6 months–1 year | 1 (6.7) | 1 (5.3) | 2 (5.9) |

| 1–5 years | 4 (26.7) | 5 (26.3) | 9 (26.5) |

| 5–10 years | 4 (26.7) | 2 (10.5) | 6 (17.6) |

| Over 10 years | 5 (33.3) | 5 (26.3) | 10 (29.4) |

Rates of QI Adherence

Rates of adherence among the components are listed in Table 3. With respect to initial diagnosis and evaluation, rates of adherence to care varied. In the initial admission history, providers assessed both stooling frequency and the presence of blood in stool in 78.3 % of cases. In 18 % of admission, stooling frequency was not asked; in 3.6 % of admissions, the presence of blood in stool was not asked. Only 36 of the 60 total admissions, or 60 %, had ESR checked on admission, whereas 59 admissions, or 98.3 %, had hemoglobin checked. In 84.7 % of eligible admissions, a GI consult was obtained within 24 h, and a same proportion of admissions had abdominal imaging evaluated. 39.7 % of eligible cases were evaluated with endoscopy within 48 h. Clostridium difficile infection was tested in 78 % of cases. Three patients were positive (7 % of those tested). Only 19 % of patients were tested for CMV (6 by immunohistochemistry on tissue biopsy; 1 by serum antibodies, 1 by serum PCR, 1 by both biopsy immunohistochemistry and serum PCR, and 1 by all three methods).

Table 3. Components of care received by Crohn's and UC patient admissions evaluated in this study defined as percentage of IBD patients who received the care component among those who were eligible.

| Component of care | Crohn's admissions (n = 20) Rate % (95 % CI) | UC admissions (n = 40) Rate % (95 % CI) | All admissions (n = 60) N/eligible, rate % (95 % CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Documentation of appropriate history (including both stooling frequency and degree of blood) | 55.0 (32.6–77.4) | 90.0 (80.6–99.4) | 47/60, 78.3 (72.0–92.0) |

| Documentation of admission examination including temperature, pulse, and evaluation of abdominal distention | 85.0 (68.4–100.0) | 97.5 (92.6–100.0) | 56/60, 93.3 (92.1–100.0) |

| Hgb and ESR obtained on admission | 60.0 (38.0–82.0) | 62.5 (47.3–77.7) | 38/60, 60.0 (47.5–72.5) |

| GI consult within 24 h of admission | 75.0 (55.5–94.5) | 89.7 (80.1–99.4) | 50/59, 84.7 (75.5–94.0) |

| IV steroids within 24 h of admission | 40.0 (18.0–62.0) | 75.7 (61.0–90.4) | 36/57, 63.2 (50.4–75.9) |

| Stooling frequency and degree of blood assessed on hospital day 3 | 85.7 (66.7–100.0) | 83.3 (69.8–96.9) | 37/44, 84.1 (73.2–95.0) |

| ESR obtained on day 3 | 21.4 (0.00–43.7) | 30.0 (13.3–46.7) | 12/44, 27.3 (14.0–40.6) |

| Rescue therapy invoked if inadequate response to steroids, as suggested by clinical prediction rules | 75.0 (26.0–100.0) | 66.7 (25.3–100.0) | 41/44, 93.1 (40.1–99.9) |

| Avoided administration of narcotics | 35.0 (13.5–56.4) | 48.7 (32.8–64.6) | 26/59, 44.1 (31.3–56.8) |

| Imaging obtained to assess for air, thumbprinting, edematous wall, or dilatation | 85.0 (68.9–100.0) | 84.6 (73.1–96.1) | 50/59, 84.7 (75.5–94.0) |

| Endoscopy within 48 h | 35.0 (13.5–56.4) | 42.1 (26.2–58.0) | 23/58, 39.7 (27.0–52.4) |

| Clostridium difficile infection testing | 65.0 (44.0–86.0) | 85.0 (73.0–96.0) | 46/59, 78.0 (67.0–89.0) |

| CMV infection testing | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 30.0 (15.0–45.0) | 10/53, 19.0 (9.0–30.0) |

| Pharmacologic DVT prophylaxis within 48 h | 50.0 (27.5–72.5) | 20.5 (7.7–33.3) | 18/59, 30.5 (18.7–42.4) |

| Discharged on a regular diet with fewer than 4 bowel movements per day | 94.7 (84.4–100.0) | 79.5 (66.6–92.3) | 49/58, 84.5 (75.1–93.9) |

| Planned follow-up within 2 weeks of discharge as stated in discharge summary | 70.0 (49.4–90.6) | 89.7 (80.1–99.4) | 49/59, 83.1 (73.4–92.7) |

| Scheduled follow-up within 2 weeks of discharge | 63.2 (40.9–85.4) | 59.0 (43.3–74.6) | 35/58, 60.3 (47.6–73.0) |

| Patient seen within 2 weeks of discharge | 52.9 (35.3–61.2) | 54.3 (35.3–61.2) | 28/52, 53.8 (35.3–61.2) |

The rates of adherence to recommended therapeutic measures are listed in Table 3. Pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis was started within 48 h in only 30.5 % of cases. Intentional avoidance of pharmacologic prophylaxis was commonly documented and attributed to GI bleed. Fifty-six percent of patients were treated with narcotics. IV steroids were started promptly in 63.2 % of the eligible cases (three patients were excluded: one who had active C. difficile infection, one who was admitted for infliximab infusion, and one who died within hours of admission). In 3.5 % of the eligible cases, oral steroids were initiated within this time frame instead. In another 3.5 % of cases, documentation showed that steroids were delayed to rule out infection. In one patient, steroids were not given due to prior psychiatric intolerance. No formal severity assessments to predict steroid response were mentioned in any admission. Stooling frequency and degree of blood were reassessed on day 3 in 84.1 % of eligible cases. ESR was obtained on day 3 in 27.3 % of eligible cases. Sixteen admissions were shorter than 3 days and not included in the analyses of these components of care. Seven patients received rescue therapy with either infliximab or adalimumab; one of those patients ultimately required surgery. Six other patients required colectomy within 3 months (4 of these patients underwent surgery during their initial admissions). One patient expired.

For discharge and follow-up, nine patients (15.5 %) were discharged before meeting suggested discharge criteria. Three of these discharges were against medical advice. The mean length of stay was 4.8 days (SD 4.6 days). Of the 60 admissions, 59 were eligible for planned follow-up 2 weeks post-discharge. 83.1 % of the eligible admissions met this component of care of planning for follow-up. A subset of 71.4 % of those patients had scheduled appointments, and only 57.1 % of this subset actually was seen in clinic within 2 weeks. When time frame for follow-up was disregarded, 80 % of admissions were seen in clinic post-discharge; with median time 16 days (mean 49.5; min 2; max 912). 6.7 % were readmitted before follow-up; 10 % were lost to follow-up; 1.7 % opted for outside follow-up; and 1.7 % expired. Overall, 53.8 % of cases that could have been seen in clinic within 2 weeks were actually seen in clinic in that time frame.

Thirty-eight admissions were eligible for all 18 components of care. The average sum of the components of care received in these cases was 11.8, or 65.8 % of the total recommended care. The minimum sum was 8, and the maximum was 17. Overall, the average percentage of applicable components of care met in admissions was 64.9 %.

In comparing quality of care between patients with Crohn's disease and patients with UC a few trends were observed. Patients with UC were more frequently asked details regarding stooling frequency and the presence of blood in stool on admission. They more often received consultation with gastroenterology specialists and IV steroids within 24 h of admission. A higher proportion of patients with UC received endoscopy within 48 h and stool infectious workup. Comparatively more patients with Crohn's disease were given pharmacologic DVT prophylaxis and appropriate discharge. The frequency that abdominal imaging was obtained was comparable between the UC and Crohn's disease groups. Additionally, the rate of post-hospital follow-up within the recommended 2-week time frame was also similar. Overall, the average percentage of applicable quality indicators met in admissions was 58.9 % for patients with Crohn's disease and 68.0 % for patients with UC.

Predictors of Quality Care

Better quality of care was inversely related to worsening anemia, leukocytosis, and degree of diarrhea. Admissions with Hgb <10 g/dl were 4.3× as likely to have over 75 % of eligible QI measures (CI 1.18–15.76). Leukocytosis over 12 k and frequency of stools over 10/day were also associated with higher quality of care (OR 1.71, 95 % CI 0.37–7.8; and OR 1.83, 95 % CI 0.52–6.39, respectively), although these odds ratios did not meet statistical significance.

Association Between Adherence to QIs and Readmission

Due to the relatively low numbers of patients in this study, the association between QI and readmission was performed as a secondary analysis only. Ten of 33 eligible patients had readmissions within 1 year of their index admission. Lack of follow-up tended to be associated with readmission within 1 year (OR 1.5, 95 % CI 0.30–7.36), although this did not meet statistical significance. There was an inverse association between the total percentage of QI factors received and readmission. The rate of readmission within 1 year of index admission for patients who received over 50 % of the factors was 10/31 (32.2 %). The rate of readmission within 1 year of index admission for patients who received <50 % of the factors was 0; however, only three patients received <50 % of factors. The rate of readmission within 1 year of index admission for patients who received over 75 % of the factors was 10/10 (100 %). The rate of readmission within 1 year of index admission for patients who received <75 % of the factors was 0/24.

Discussion

Inflammatory bowel disease is a chronic condition associated with frequent exacerbations and high costs related to hospitalizations [3, 6]. Our data measure the degree to which IBD patients at the San Diego VA Medical Center received recommended services and highlight areas of improvement for quality of care. These areas include obtaining inflammatory marker levels on admission and hospital day 3 in order to use them in educated treatment decisions, treating patients who have disease severe enough to require hospitalization with IV steroids in a timely fashion, utilizing pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis, avoiding administration of narcotics, and scheduling follow-up after discharge.

Quality indicators and evidence-based guidelines have been defined for a variety of gastroenterology-related diseases. A study examining the quality of care provided to VA patients with cirrhosis and ascites revealed that care was suboptimal but improved when gastroenterologists were involved [19]. Similarly, a study using Medicare-proposed quality indicators for patients with chronic hepatitis C infection showed variable proportions of patients meeting standards of care [20]. A recent paper discussing quality improvement in IBD highlighted the variability in care given amidst several evidence-based guidelines for best practices in IBD [21]. However, these guidelines do not focus on acute inpatient care [22, 23]. Pola et al. suggested strategies for inpatient care for patients with UC, but few, if any, studies have evaluated the level of quality of care in patients with IBD.

Several studies describe the increased risk of deep venous thrombosis in patients with UC, particularly during acute flares [24, 25]. Hospitalized IBD patients have three times the risk of VTE compared with non-IBD inpatients [26–28]. The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines recommend that physicians consider heparin prophylaxis in UC patients hospitalized for severe flares [23], whereas the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommends low molecular weight heparin for all hospitalized IBD patients [29]. Despite these principles, providers seem concerned about giving pharmacological prophylaxis in the setting of rectal bleeding. A survey study published by Tinsley et al. [27] showed that although 80.6 % of responders believed that hospitalized IBD patients were at greater VTE risk, only 34.6 % would give pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis to hospitalized patients with severe UC.

Whereas 78 % of eligible admissions in our study received C. difficile testing, only 19 % received CMV testing. The need to identify C. difficile infection in patients with acute UC flare has historically been an area of discussion [30–32]. Most recent studies have reported negative effects on IBD outcome, such as extended lengths of stay and higher surgery rates [33–35]. The role of CMV colitis has also been under investigation. Although testing and need for treatment has been debated, one study found that after antiviral therapy, IBD colitis remission rates were 67–100 % [36]. Current guidelines recommend evaluating both of these infections [1, 9, 10].

The relevance of QI to patient outcomes in IBD remains to be determined. In our exploratory analysis, readmission tended to be related to lack of follow-up and was inversely related to the overall receipt of QI indicators. The latter was most due to the fact that patients who were more severely ill were significantly more likely to receive more QI. This is not surprising and reflects a continuum of clinical judgments in patient care. These data suggest that guidelines may be further tailored to reflect the severity of illness among hospitalized patients. Other outcome measures such as patient symptoms and duration, patient adherence, length of hospitalization, and satisfaction were not measured. Overall, very large numbers of patients would need to be analyzed to determine whether there is an overall or specific relation of QI to hard clinical outcomes such as readmission or mortality. In addition, we found that patients with IBD have multiple comorbidities requiring multiple hospitalizations. Overall, the 34 patients in this cohort were hospitalized 135 times over 7 years, with 35 % of hospitalizations not related to IBD. Therefore, these represent high-cost/high-risk patients that warrant focused case management or other interventions to minimize the need for hospitalization.

Our study has several other limitations. First, this is a single-center study that may not be representative of other centers. This was a low-volume, non-referral center hospital for IBD, and patient identification may have been limited by the use of ICD-9 code only. In addition, this center represents a relatively low-volume practice, with hospitalizations for IBD colitis flares occurring approximately once per month. As a result, the medical and GI consult teams could be expected to be less familiar with practice guidelines. However, other studies of adherence to quality guidelines related to gastroenterology and IBD have shown similar gaps in care [21, 37]. Recently, Ananthakrishnan et al. [38] reported prospective data from 7 major IBD centers in the USA and found that even among high-volume academic centers, there was a significant variation in the use of immunomodulators drug therapy, indicating unexplained practice variation at the highest levels of academic practice. This study does not consider any rational decision-making with respect to discrepancies between observed and recommended care. Documentation in the medical record suggested that many providers delayed administering IV steroids until infection was ruled out. Providers also opted not to give pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis due to concern that patients with flares had gastrointestinal bleeding. This observational retrospective study also does not consider comorbid conditions. Last, the medical record may not have recorded whether these patients had additional outside admissions or follow-up; however, the use of out-of-system care is not common among patients enrolled in VA care.

Finally, readmission and follow-up are important components of IBD disease management evaluated in this study, but patient adherence to the treatment plan is also important and uncontrolled by providers. Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that 40–60 % of UC patients are non-adherent (typically defined as taking <80 % of their medication) [39–41]. Non-adherence has been associated with a fivefold increase in the risk of relapse [40, 42] and higher costs [41]. These studies represent further areas for potential improvements in care.

In conclusion, our review of patients with IBD admitted to the general medicine service suggests areas of high quality of care, such as getting specialty consultants involved in cases early, making necessary adjustments with rescue therapy or surgical consultation, and ensuring that patients are stable enough for discharge. Other areas are in need of improvement, particularly timely delivery of IV steroids, avoidance of narcotics, utilization of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis, and scheduling follow-up. These findings suggest that interventions and quality improvement efforts are warranted, and could include increased teaching related to current treatment guidelines, admission checklists, standardized consultation procedures, and facilitated follow-up planning. Further studies would be useful to test intervention strategies for practice improvement.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Affairs HSR&D, and Office of Public Health/Clinical Public Health (10P3B). Samuel B. Ho, MD, has received research and grant support from Genetech, Inc., Vital Therapies, Inc., Aspire Bariatrics, Inc., Prime Education, Inc., Abbvie, Inc., and Gilead, Inc.

Abbreviations

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel disease

- VHA

Veterans Health Administration

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards: Conflicts of interest None.

References

- 1.Danese S, Fiocchi C. Ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1713–1725. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1102942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gunnarsson C, Chen J, Rizzo JA, Ladapo JA, Naim A, Lofland JH. The employee absenteeism costs of inflammatory bowel disease: evidence from US National Survey Data. J Occup Environ Med. 2013;55:393–401. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31827cba48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murthy SK, Steinhart AH, Tinmouth J, Austin PC, Nguyen GC. Impact of gastroenterologist care on health outcomes of hospitalised ulcerative colitis patients. Gut. 2012;61:1410–1416. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen RD, Yu AP, Wu EQ, Xie J, Mulani PM, Chao J. Systematic review: the costs of ulcerative colitis in Western countries. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:693–707. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Langenberg DR, Simon SB, Holtmann GJ, Andrews JM. The burden of inpatient costs in inflammatory bowel disease and opportunities to optimize care: a single metropolitan Australian center experience. J Crohn's Colitis. 2010;4:413–421. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lichtenstein GR, Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ. Practice parameters Committee of American College of G. Management of Crohn's disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:465–483. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bewtra M, Su C, Lewis JD. Trends in hospitalization rates for inflammatory bowel disease in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:597–601. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernstein CN, Nabalamba A. Hospitalization, surgery, and readmission rates of IBD in Canada: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:110–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pola S, Patel D, Ramamoorthy S, et al. Strategies for the care of adults hospitalized for active ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1315–1325. e1314. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bitton A, Buie D, Enns R, et al. Treatment of hospitalized adult patients with severe ulcerative colitis: Toronto consensus statements. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:179–194. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hovde O, Moum BA. Epidemiology and clinical course of Crohn's disease: results from observational studies. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1723–1731. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i15.1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kottke TE. Simple rules that reduce hospital readmission. Perm J. 2013;17:91–93. doi: 10.7812/TPP/13-024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim AH, Grafton R, Hetzel DJ, Andrews JM. Clinical audit: recent practice in caring for patients with acute severe colitis compared with published guidelines—is there a problem? Intern Med J. 2013;43:803–809. doi: 10.1111/imj.12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Truelove SC, Witts LJ. Cortisone in ulcerative colitis; final report on a therapeutic trial. Brit Med J. 1955;2:1041–1048. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4947.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Truelove SC, Jewell DP. Intensive intravenous regimen for severe attacks of ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 1974;1:1067–1070. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)90552-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harvey RF, Bradshaw JM. A simple index of Crohn's-disease activity. Lancet. 1980;1:514. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)92767-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho GT, Mowat C, Goddard CJ, et al. Predicting the outcome of severe ulcerative colitis: development of a novel risk score to aid early selection of patients for second-line medical therapy or surgery. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:1079–1087. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.James PA, Hartz AJ, Levy BT. Specialty of ambulatory care physicians and mortality after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1288–1289. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200303273481316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Buchanan P, et al. The quality of care provided to patients with cirrhosis and ascites in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:70–77. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanwal F, Schnitzler MS, Bacon BR, Hoang T, Buchanan PM, Asch SM. Quality of care in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:231–239. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-4-201008170-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melmed GY, Siegel CA. Quality improvement in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol & Hepatol. 2013;9:286–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter MJ, Lobo AJ, Travis SP. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2004;53:V1–V16. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.043372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kornbluth A, Sachar DB. Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults: American College of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:501–523. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grainge MJ, West J, Card TR. Venous thromboembolism during active disease and remission in inflammatory bowel disease: a cohort study. Lancet. 2010;375:657–663. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61963-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen GC, Yeo EL. Prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism in IBD. Lancet. 2010;375:616–617. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen GC, Sam J. Rising prevalence of venous thromboembolism and its impact on mortality among hospitalized inflammatory bowel disease patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2272–2280. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tinsley A, Naymagon S, Trindade AJ, Sachar DB, Sands BE, Ullman TA. A survey of current practice of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in hospitalized inflammatory bowel disease patients in the United States. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:e1–e6. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31824c0dea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Houston DS, Wajda A. The incidence of deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism among patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based cohort study. Thromb Haemost. 2001;85:430–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition) Chest. 2008;133:381S–453S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rolny P, Jarnerot G, Mollby R. Occurrence of Clostridium difficile toxin in inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1983;18:61–64. doi: 10.3109/00365528309181560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weber P, Koch M, Heizmann WR, Scheurlen M, Jenss H, Hartmann F. Microbic superinfection in relapse of inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;14:302–308. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199206000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mylonaki M, Langmead L, Pantes A, Johnson F, Rampton DS. Enteric infection in relapse of inflammatory bowel disease: importance of microbiological examination of stool. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:775–778. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000131040.38607.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sinh P, Barrett TA, Yun L. Clostridium difficile infection and inflammatory bowel disease: a review. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2011;2011:136064. doi: 10.1155/2011/136064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ananthakrishnan AN, Guzman-Perez R, Gainer V, et al. Predictors of severe outcomes associated with Clostridium difficile infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:789–795. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05022.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Navaneethan U, Mukewar S, Venkatesh PG, Lopez R, Shen B. Clostridium difficile infection is associated with worse long term outcome in patients with ulcerative colitis. J Crohn's Colitis. 2012;6:330–336. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kandiel A, Lashner B. Cytomegalovirus colitis complicating inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2857–2865. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weizman AV, Nguyen GC. Quality of care delivered to hospitalized inflammatory bowel disease patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:6360–6366. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i38.6360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ananthakrishnan AN, Kwon J, Raffals L, et al. Variation in treatment of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases at major referral centers in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1197–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kane SV, Cohen RD, Aikens JE, Hanauer SB. Prevalence of nonadherence with maintenance mesalamine in quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2929–2933. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kane SV, Robinson A. Review article: understanding adherence to medication in ulcerative colitis—innovative thinking and evolving concepts. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:1051–1058. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mitra D, Hodgkins P, Yen L, Davis KL, Cohen RD. Association between oral 5-ASA adherence and health care utilization and costs among patients with active ulcerative colitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:132. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kane S, Huo D, Aikens J, Hanauer S. Medication nonadherence and the outcomes of patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Med. 2003;114:39–43. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]