Abstract

Organismal fitness depends on adaptation to complex niches where chemical compounds and pathogens are omnipresent. These stresses can lead to the fixation of alleles in both xenobiotic responses and proliferative signaling pathways that promote survival in these niches. However, both xenobiotic responses and proliferative pathways vary within and among species. For example, genetic differences can accumulate within populations because xenobiotic exposures are not constant and selection is variable. Additionally, neutral genetic variation can accumulate in conserved proliferative pathway genes because these systems are robust to genetic perturbations given their essential roles in normal cell-fate specification. For these reasons, sensitizing mutations or chemical perturbations can disrupt pathways and reveal cryptic variation. With this fundamental view of how organisms respond to cytotoxic compounds and cryptic variation in conserved signaling pathways, it is not surprising that human patients have highly variable responses to chemotherapeutic compounds and to the activities of proliferative pathways. These different patient responses result in the low FDA-approval rates for chemotherapeutics and underscore the need for new approaches to understand these diseases and therapeutic interventions. Model organisms, especially the classic invertebrate systems of Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster, can be used to combine studies of natural variation across populations with responses to both xenobiotic compounds and chemotherapeutics targeted to conserved proliferative signaling pathways.

Xenobiotic and targeted chemotherapeutic drug responses vary across natural populations

In their natural habitats, metazoans are exposed to small molecules produced by bacteria, fungi, and plants as defense mechanisms to prevent predation. Modern medicinal chemistry has employed these cytotoxic small molecules to treat human diseases, so that approximately 70% of cancer chemotherapeutics (hereafter chemotherapeutics) developed from 1981–2010 were derived originally from natural products [1]. Oftentimes, these small molecules disrupt essential cellular processes and can act as strong selective pressures that reduce genetic diversity [2]. By contrast, the combinations of small molecules in ecological niches change over time and can maintain genetic diversity within a species through balancing selection [3]. In addition to xenobiotic compounds, targeted chemotherapeutics specifically perturb the signaling pathways mutated in human cancers and are often lauded as great successes. However, because these proliferative signaling pathways have evolved mechanisms to withstand the accumulation of genetic variation within populations, chemotherapeutics have variable efficacies across a wide-range of genetically distinct patients [4]. Therefore, for both xenobiotic and targeted chemotherapeutics, it is not surprising that responses to chemotherapeutics are highly variable among the human population [5].

This variability in patient responses to chemotherapeutics can be caused by differences in the drug mechanism of action, absorption, metabolism, and elimination. Additionally, these processes can be impacted by germline variation, rare somatic mutations in the target tumor, environmental factors, and interactions among these factors and others [5]. This complexity results in a narrow range of concentrations that cause maximal tumor clearance among patients (defined as the therapeutic index). Also, chemotherapeutics are the most toxic drugs that are prescribed and cause severe and variable side effects among patient populations, thereby limiting the therapeutic index. In order to tailor treatments to individuals, drug responses must be correlated with genetic variants in specific patients. These data provide markers to broaden the therapeutic index for specific patients. This identification of genetic determinants that contribute to variability in patient responses to chemotherapeutics largely depends on the sample size of the patient population, the allele frequency and effect size of the causative variant(s), and the reliability of the responses being measured [6]. These factors are limited in clinical oncology because it is extremely difficult to acquire large cohorts of patients that undergo the same therapeutic regimen [7], the high levels of genetic heterogeneity present in tumor [8] and patient populations [9], and the confounding effects of environmental variability [10,11]. As a result, only 6.4% of anti-cancer compounds in phase I clinical trials become FDA-approved chemotherapeutics, which is the lowest of any drug class [12]. Even if these limitations were resolved and genetic markers were associated with variable chemotherapeutic responses, the underlying mechanisms that are affected by the causal genetic variants would remain unknown, limiting clinical applications to recommendations based solely on genetic information.

In this review, we will highlight recent developments using invertebrate model organisms to better understand mechanisms of chemotherapeutic responses and discuss approaches to determine the effects of natural genetic variation on these responses. We contend that quantitative analyses of chemotherapeutic responses across different genetic backgrounds will increase the likelihood that new anti-cancer compounds will receive FDA approval and will augment the efficacies of existing chemotherapeutics.

Chemotherapeutic drug responses are conserved in invertebrate models

The invertebrate model organisms, C. elegans and D. melanogaster, have long facilitated the discoveries of molecular mechanisms associated with therapeutic responses [13,14]. These systems enable the study of chemotherapeutic effects because xenobiotic-response pathways are highly conserved between invertebrates and humans [15], including cytochrome P450s [16,17], UDP-glucuronosyltransferases [2], and ABC transporters [18]. Similarly, numerous additional examples of responses to cytotoxic chemotherapeutics conserved between D. melanogaster and humans are known [21]. Additionally, the utility of C. elegans and D. melanogaster can be extended to chemotherapeutics that target cell proliferation pathways often constitutively activated in human cancers [22]. Because most of these pathways were discovered and characterized in studies of C. elegans vulval development and D. melanogaster compound eye development [23], the relevance of tractable models to understand conserved signaling pathways is long-standing. Cellular overproliferation associated with activating mutations in Ras pathway components have been shown to be conserved among C. elegans, D. melanogaster, and humans [24,25]. For example, the severities of different activating mutations in the Ras pathway kinase, MEK1, and the suppressive effects of a MEK1 inhibitor have the same rank orders between invertebrates and vertebrates [26]. Although this highlighted example and others are important for the understanding of cytotoxic and targeted chemotherapeutic responses, most studies have been performed only in a single genetic background without any consideration of natural genetic variation.

The effect of genetic background on chemotherapeutic drug responses

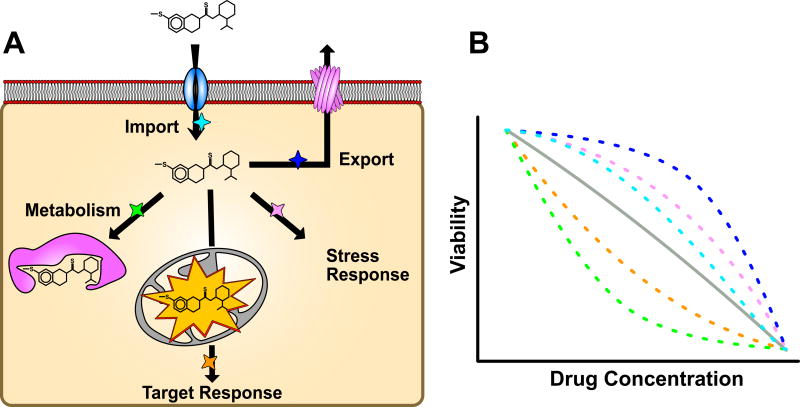

Individuals across populations harbor seemingly neutral genetic variation that causes phenotypic differences in the presence of chemical perturbations (Figure 1). This cryptic variation can cause large and divergent responses to chemotherapeutic regimens across cancer patient populations. Pharmacogenetics, pharmacogenomics, and genome-wide association studies of patient responses to chemotherapeutics focus on the identification and characterization of this genetic variation, but few broadly applicable results have been obtained [27]. Therefore, new approaches must be taken to understand how physiological responses to chemotherapeutics are affected by the genetic makeup of an individual without the difficulties associated with clinical oncology studies.

Figure 1. Natural variation alters cellular responses to a xenobiotic.

(A) The cellular response to a xenobiotic that affects mitochondrial function and organismal viability. Arrows represent steps in the xenobiotic response and colored stars next to arrows represent possible points where genetic variation can alter the response. (B) Organism viability as a function of xenobiotic drug concentration for multiple genetic backgrounds, represented by colored dashed lines (average of backgrounds in gray), is shown. The potential reasons for altered xenobiotic responses are shown as different colors, increased viability results from increased xenobiotic export (dark blue), increased viability results from an increased cellular stress response (pink), increased viability results from decreased xenobiotic import (cyan), decreased viability results from increased target affinity (orange), decreased viability results from reduced metabolism (green). Importantly, the effect of the variant can be altered by the effects of other variants in the genetic background.

The D. melanogaster and C. elegans communities have developed numerous strain resources with divergent genetic backgrounds, including wild isolates with whole-genome sequence data [28–30] and recombinant inbred lines (RILs) generated by crossing distinct genetic backgrounds [31–33]. Across both species, drug responses generally affect fitness, including offspring production, growth rate, and viability. High-throughput assays have been developed to quantify these traits across a large number of individuals in tightly controlled environmental conditions. When applied to studying the effects of chemotherapeutics on diverse genetic backgrounds, these powerful assays enable the identification of genomic regions (quantitative trait loci or QTL) that vary across the population and are predictive of drug response [21,31,34] because environmental conditions are strictly controlled, drug responses from large numbers of divergent individuals can be measured, and high levels of replication can be obtained. Additionally, the abundance of genome-editing tools available in both species facilitate the functional validation and molecular characterization of genetic variants associated with chemotherapeutic responses [35,36]. Through these resources, assays, and genetic tools, investigators can rapidly go from a difference in drug response to the variant underlying that phenotypic difference.

In D. melanogaster, one collection of genetically divergent wild strains [29,30] and another collection of recombinant inbred strains [33] have been exposed to a variety of abiotic stresses and chemical perturbations. It was found that most responses to chemotherapeutic compounds are highly heritable [37], suggesting that variants controlling drug response differences exist in these populations. However, few examples of drug response QTL have been connected to a causal genetic variant (or QTL in general [38]). One notable exception came from studies using the Drosophila Synthetic Population Resource [39], where variable responses to methotrexate were mapped to three QTL that each contain candidate genes conserved with humans and previously implicated in methotrexate toxicity. Additionally, responses to tunicamycin were mapped using the Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel [30] to a large number of loci but none of these loci were shown to play a direct role in the variable drug response [40]. In a global approach, a large-scale expression study of 80 inbred D. melanogaster strains from the Drosophila Genetic Reference Panel found 2,000 genes with variable expression that can be explained by genetic differences in the panel, referred to expression quantitative trait loci or eQTL [41]. Interestingly, significant differences in mRNA expression of approximately 20 glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) and cytochrome P450 genes, which have roles in xenobiotic responses, were observed among these strains, suggesting that natural variability to metabolize xenobiotics likely exists among these strains [41]. As another example, European populations of D. melanogaster harbor a deletion in the 3’ UTR of the metallothionein A (MtnA) gene that results in a four-fold increase in MtnA expression [42]. This increased expression of MtnA results in decreased resistance to oxidative stress, which is a defining characteristic of cancer cells [43], as compared to the ancestral population. Expression levels of the human homologs of MtnA have been shown to have variable expression levels across different cancer types, and increased expression of metallothionein genes have been associated with resistance to the ROS-inducing chemotherapeutics cisplatin and bleomycin [44]. Though many studies indicate that the D. melanogaster species has heritable responses to chemotherapeutics, further investigations into the specific genetic causes of this variability are required to inform conserved drug response mechanisms.

Recently, the molecular mechanism associated with natural differences in C. elegans responses to topoisomerase II poisons was identified [45]. This study leveraged a high-throughput assay to quantify the drug responses in a population of wild strains and recombinant inbred lines. A large-effect QTL was identified, and a causal variant in the C. elegans homolog of a topoisomerase II gene was validated using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. Furthermore, genome editing of the conserved variant site in human cells recapitulated the results from C. elegans, providing a functionally validated model of differential toxicity associated with topoisomerase II poison treatment in cancer patients. This combination of natural variation, high-throughput assays, and genome-editing technologies available only in model organisms enables similar approaches to understand responses to other cytotoxic compounds.

The effect of genetic background on the signaling pathways targeted by chemotherapeutics

Much like in xenobiotic responses, organisms have evolved mechanisms to ensure that phenotypes remain constant in the presence of genetic and environmental perturbations [46]. This robustness is exemplified by similar levels of Ras/MAPK pathway ligand expression found between two genetically divergent species of nematodes, C. elegans and Oscheius tipulae [47]. Despite the inherent buffering that these proliferative pathways maintain to reduce the effects of diverse genetic perturbations, cancer-causing mutations disrupt these pathways beyond their suppressive capacities. These disruptive mutations sensitize proliferative pathways to the effects of previously phenotypically silent genetic differences among individuals. To improve the effectiveness of chemotherapeutic regimens, the interactions between genetic background and mutations that cause cancer must be characterized. Currently, it is extremely difficult to identify background variants that modulate the effects of sensitizing mutations and chemotherapeutic responses across diverse human populations because too few patients with variable responses are identified and genotyped. However, by introducing mutations that sensitize proliferative pathways in diverse model organism genetic backgrounds, it is possible to reveal genetic variants that influence both cancer progression and drug responses.

A recent study highlighted how C. elegans can be used to identify genetic variants that modify the ectopic proliferation phenotype of an oncogenic Ras mutation [48]. The authors observed that genetically diverged C. elegans strains harboring the same gain-of-function (GoF) allele of the C. elegans Ras homolog exhibited variable severity of a vulva hyperproliferation defect. To identify the genetic background differences that could influence Ras pathway activity, the authors quantified vulva hyperproliferation in a collection of recombinant strains constructed from two genetically diverged strains with the same GoF allele. This approach led to the identification of three QTL that modify the expressivity of the vulva hyperproliferation defect. Next, the authors functionally validated the amx-2 gene, which underlies one of the identified QTL, as an inhibitor of Ras/MAPK signaling in C. elegans [48]. Interestingly, the closest human homolog of AMX-2 has been shown to be downregulated in a wide-range of cancer types and is widely used as an early indicator of cancer [49]. This and similar experiments in C. elegans highlight the power of testing the effect of oncogenic mutations in multiple genetic backgrounds [50,51]. However, further insights can be gained by incorporating targeted chemotherapeutic treatments along with cancer-causing mutations. For example, the oncogenic recombinant lines generated in this study can be used to identify the genetic modifiers of targeted Ras and other chemotherapeutic kinase inhibitors. This combination of sensitized cancer-causing pathways with chemotherapeutic drug responses in model organisms Studying the effects of chemotherapeutics on diverse genetic backgrounds that contain cancer-causing mutations is only feasible in model organisms and is a powerful approach to elucidate the mechanisms associated with variable therapeutic responses among patients.

The transgenic expression of human oncogenic mutations has been used recently in D. melanogaster to identify optimal combinations of chemotherapeutics that suppress tumor-related phenotypes [52]. Human genome rearrangements commonly found in papillary thyroid carcinomas fuse the RET receptor tyrosine kinase gene, which promotes cell growth, proliferation, survival, and differentiation through the activation of downstream targets [53], with either CCDC6 or NCOA4. Levinson and Cagan used the D. melanogaster GAL4/UAS transcriptional activation system to drive the expression of these fusion proteins [54] and cause higher levels of activated RET, organism lethality, and cell migration, which is a phenotype associated with epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition [55]. The authors systematically tested each of the genes within the Drosophila kinome and identified 15 druggable kinases that suppressed the tumor-related phenotypes caused by fusion protein overexpression. Only two of the downstream kinases suppressed phenotypes caused by both of the RET fusions, which is surprising because the fusions share an identical RET kinase domain. Using these genetic interaction data, the authors identified chemical inhibitors of the downstream kinases that suppress the tumor-related phenotypes in the Drosophila model. This study highlights the utility of Drosophila cancer models for the characterization of signaling pathways that are disrupted by oncogenes and the optimization of therapeutic interventions to mitigate cancer promotion. Given the variability in patient responses to targeted chemotherapeutics, it would be interesting to see how consistent the effects of the fusion proteins and targeted chemotherapeutics are in the context of different genetic backgrounds.

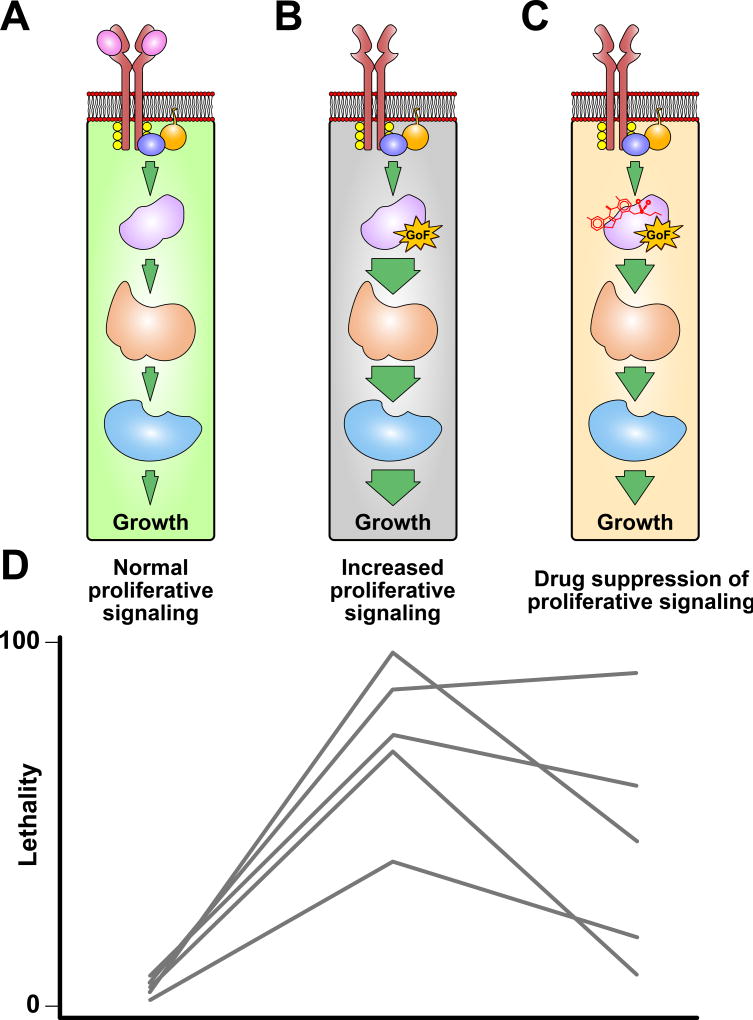

The two studies described above demonstrate the power of model organisms to study the effects of oncogenic mutations that sensitize proliferative signaling pathways. The C. elegans approach taken by Schmid et al. identified genetic modifiers of an oncogenic Ras mutation but did not study the effects of targeted chemotherapeutics. The Drosophila approach taken by Levinson and Cagan addressed the effects of targeted chemotherapeutics but did not study the effects of genetic background on the response. The principles of studies can be combined to elucidate how genetic background modifies chemotherapeutic drug responses (Figure 2). However, given the large number of genetically distinct C. elegans [28] and D. melanogaster [30] strains, diversity of cancer-driving mutations in conserved signaling pathways, and panoply of targeted chemotherapeutic drugs, the possible combinations are seemingly endless. To combat this scaling issue, newly created high-throughput methods [21,31,34] enable the quantification of tumor-related phenotypes across divergent genetic backgrounds, sensitizing pathway mutations, and drugs.

Figure 2. Natural variation modifies effects of sensitizing pathway mutations and chemotherapeutic responses.

A) A simplified cellular signaling pathway that results in proliferative growth upon ligand (pink) binding is shown. B) The proliferative signaling pathway from A is shown with a gain-of-function (GoF) mutation that results in increased pathway activity and cellular proliferation that is independent of ligand binding. The size of the arrows that connect the steps in the pathway correspond to the amount of pathway activation. C) The sensitized pathway from B is treated with a chemotherapeutic to suppress the effects of the GoF mutation. D) The lethality phenotypes associated with each pathway (A–C) are shown for five diverged Drosophila genetic backgrounds represented by different gray lines. All five genetic background exhibit little-to-no lethality with normal pathway activity. However, low levels of lethality might occur with normal pathway activity because laboratory growth conditions may not be ideal for diverged genetic backgrounds. Introduction of a sensitizing GoF mutation (gray) results in increased signaling activity, uncontrolled cellular growth, and animal lethality. However, the mutation affects each genetic background differently. This variability can be caused by various modifying variants present in the five strains that have no visible effect with normal signaling activity. Similarly, chemotherapeutic-induced suppression of pathway signaling activity and organism lethality associated with the GoF allele varies among genetic backgrounds. The variable efficacy of the chemotherapeutic to suppress lethality may result from a number of reasons, some of which are discussed in Figure 1.

Where do we go from here?

The novel invertebrate systems discussed here have taken crucial steps toward unraveling the complexity of cancer and responses to associated chemotherapeutic interventions [37,45,48,54,56,57]. However, we contend that the benefit of these invertebrate systems has not been fully realized because drug response measurements and natural variation are rarely combined. Additional large-scale experiments that quantify xenobiotic responses across diverse genetic backgrounds, which have the power to identify variants with no observable fitness consequence in normal conditions [37,40,45,58], are required to expand our understanding of how conserved pathways accumulate cryptic variation revealed by drug exposure. Similarly, large-scale experiments that look at the effect of genetic background on sensitizing oncogenic mutations and responses to targeted chemotherapeutics, facilitate the simultaneous identification of genetic modifiers of the sensitizing mutation and novel targeted chemotherapeutic combinations. Of course, findings across diverse invertebrate genetic backgrounds might not assure success when translated to human patients. However, we posit that the likelihood of translation will be greater if validated in multiple genetic backgrounds and interesting new discoveries about how genetic diversity influences xenobiotic responses and conserved signaling pathways will undoubtedly be discovered.

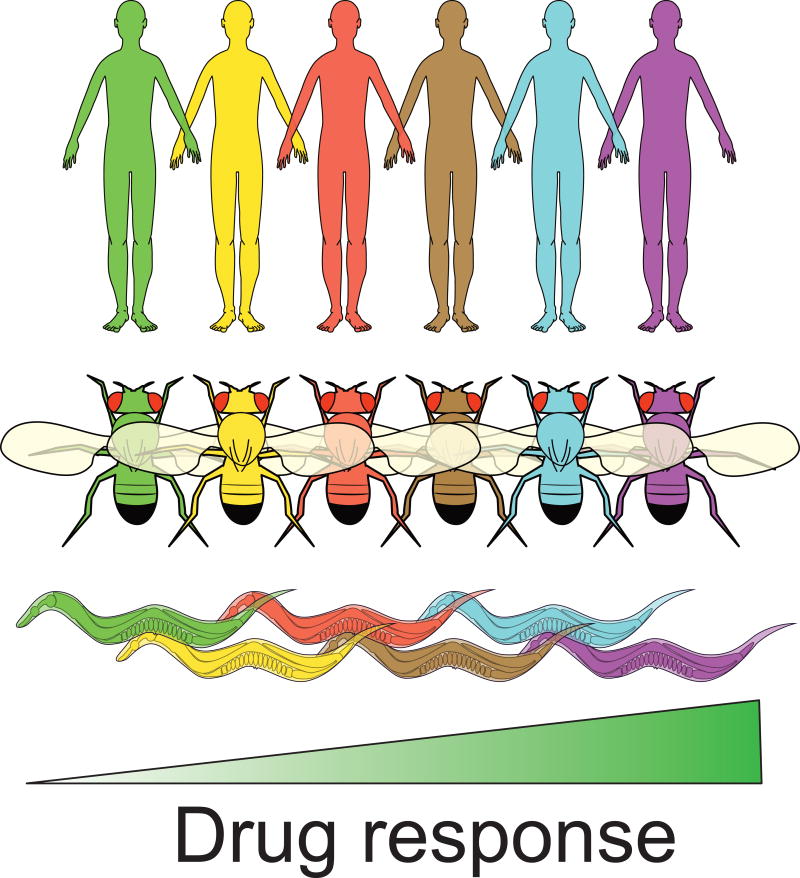

Summary Figure.

Individuals within the human population vary in their responses to antineoplastic drugs based on their genetic background. Five unique human, Caenorhabditis elegans, and Drosophila melanogaster genetic backgrounds with variable drug responses are represented above with different colors. The identification of specific genetic differences within the human population that underlie variable drug responses is a central goal of modern medicine, but remains challenging because of the highly heterogeneous human genome and lack of tractability of human studies. However, recent studies have shown that there is substantial variability in antineoplastic drug responses among individuals within the classic invertebrate species C. elegans and D. melanogaster. The conservation of variable antineoplastic drug responses in these model species suggests that common mechanisms may be affected by genetic differences within each species. We argue the tractability of these systems will enable the identification of specific genetic variants that underlie variable drug responses.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank members of the Andersen laboratory for critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported by a National Institutes of Health R01 subcontract to E.C.A. (GM107227), the Chicago Biomedical Consortium with support from the Searle Funds at the Chicago Community Trust, a Sherman-Fairchild Cancer Innovation Award to E.C.A., and an American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grant to E.C.A. (127313-RSG-15-135-01-DD), along with support from the Cell and Molecular Basis of Disease training grant (T32GM008061) to S.Z.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the 30 years from 1981 to 2010. J Nat Prod. 2012;75:311–335. doi: 10.1021/np200906s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bock KW. The UDP-glycosyltransferase (UGT) superfamily expressed in humans, insects and plants: Animal-plant arms-race and co-evolution. Biochem Pharmacol. 2016;99:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Russell RJ, Scott C, Jackson CJ, Pandey R, Pandey G, Taylor MC, et al. The evolution of new enzyme function: lessons from xenobiotic metabolizing bacteria versus insecticide-resistant insects. Evol Appl. 2011;4:225–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2010.00175.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prasad V, Fojo T, Brada M. Precision oncology: origins, optimism, and potential. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:e81–6. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00620-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner RM, Park BK, Pirmohamed M. Parsing interindividual drug variability: an emerging role for systems pharmacology. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2015;7:221–241. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sham PC, Purcell SM. Nature Publishing Group. Vol. 15. Nature Publishing Group; 2014. Statistical power and significance testing in large-scale genetic studies; pp. 335–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Low S-K, Chung S, Takahashi A, Zembutsu H, Mushiroda T, Kubo M, et al. Genome-wide association study of chemotherapeutic agent-induced severe neutropenia/leucopenia for patients in Biobank Japan. Cancer Sci. 2013;104:1074–1082. doi: 10.1111/cas.12186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koboldt DC, Steinberg KM, Larson DE, Wilson RK, Mardis ER. The next-generation sequencing revolution and its impact on genomics. Cell. 2013;155:27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McClellan J, King M-C. Genetic heterogeneity in human disease. Cell. 2010;141:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu J, Huang J, Zhang Y, Lan Q, Rothman N, Zheng T, et al. Identification of gene-environment interactions in cancer studies using penalization. Genomics. 2013;102:189–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunter DJ. Gene-environment interactions in human diseases. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:287–298. doi: 10.1038/nrg1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hay M, Thomas DW, Craighead JL, Economides C, Rosenthal J. Clinical development success rates for investigational drugs. Nature Publishing Group, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited. All Rights Reserved. 2014;32:40–51. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaletta T, Hengartner MO. Finding function in novel targets: C. elegans as a model organism. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:387–398. doi: 10.1038/nrd2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pandey UB, Nichols CD. Human disease models in Drosophila melanogaster and the role of the fly in therapeutic drug discovery. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63:411–436. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santos R, Ursu O, Gaulton A, Bento AP, Donadi RS, Bologa CG, et al. A comprehensive map of molecular drug targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:19–34. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.230. A comprehensive overview of drug targets that are conserved in all commonly used model organisms. This excellent resource helps to prioritize what chemotherapeutics are best suited for studies in model organisms. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawashima A, Satta Y. Substrate-dependent evolution of cytochrome P450: rapid turnover of the detoxification-type and conservation of the biosynthesis-type. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100059. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harlow PH, Perry SJ, Widdison S, Daniels S, Bondo E, Lamberth C, et al. The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans as a tool to predict chemical activity on mammalian development and identify mechanisms influencing toxicological outcome. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22965. doi: 10.1038/srep22965. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiong J, Feng J, Yuan D, Zhou J, Miao W. Tracing the structural evolution of eukaryotic ATP binding cassette transporter superfamily. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16724. doi: 10.1038/srep16724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meier B, Cooke SL, Weiss J, Bailly AP, Alexandrov LB, Marshall J, et al. C. elegans whole-genome sequencing reveals mutational signatures related to carcinogens and DNA repair deficiency. Genome Res. 2014;24:1624–1636. doi: 10.1101/gr.175547.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szikriszt B, Póti Á, Pipek O, Krzystanek M, Kanu N, Molnár J, et al. A comprehensive survey of the mutagenic impact of common cancer cytotoxics. Genome Biol. 2016;17:99. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0963-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yadav AK, Srikrishna S, Gupta SC. Cancer Drug Development Using Drosophila as an in vivo Tool: From Bedside to Bench and Back. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2016;37:789–806. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2016.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aaron Hobbs G, Der CJ, Rossman KL. RAS isoforms and mutations in cancer at a glance. Journal of Cell Science. 2016 doi: 10.1242/jcs.182873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaye DD, Greenwald I. OrthoList: a compendium of C. elegans genes with human orthologs. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reiner DJ, Lundquist EA. Small GTPases. WormBook. 2016 doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.67.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goyal Y, Jindal GA, Pelliccia JL, Yamaya K, Yeung E, Futran AS, et al. Nature Publishing Group. Vol. 49. Nature Publishing Group; 2017. Divergent effects of intrinsically active MEK variants on developmental Ras signaling; pp. 465–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jindal GA, Goyal Y, Yamaya K, Futran AS, Kountouridis I, Balgobin CA, et al. In vivo severity ranking of Ras pathway mutations associated with developmental disorders. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2017;114:510–515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1615651114. The authors observed that the severities of developmental phenotypes associated with common RASopathy and cancer mutations are correlated among zebrafish, Drosophila, and human patient populations, establishing novel model systems to study the effects of these mutations. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Relling MV, Evans WE. Pharmacogenomics in the clinic. Nature. 2015;526:343–350. doi: 10.1038/nature15817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cook DE, Zdraljevic S, Roberts JP, Andersen EC. CeNDR, the Caenorhabditis elegans natural diversity resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lack JB, Lange JD, Tang AD, Corbett-Detig RB, Pool JE. A Thousand Fly Genomes: An Expanded Drosophila Genome Nexus. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:3308–3313. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang W, Massouras A, Inoue Y, Peiffer J, Ràmia M, Tarone AM, et al. Natural variation in genome architecture among 205 Drosophila melanogaster Genetic Reference Panel lines. Genome Res. 2014;24:1193–1208. doi: 10.1101/gr.171546.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andersen EC, Shimko TC, Crissman JR, Ghosh R, Bloom JS, Seidel HS, et al. A Powerful New Quantitative Genetics Platform, Combining Caenorhabditis elegans High-Throughput Fitness Assays with a Large Collection of Recombinant Strains. G3. Genetics Society of America. 2015;5:g3.115.017178–920. doi: 10.1534/g3.115.017178. The authors constructed a panel of 359 recombinant inbred advanced intercross strains from two diverged C elegans strains that can be used to associated genetic variation with phenotypic variation. Additionally, the authors described a high-throughput and highly accuracy platform for quantifying various animal phenotypes associated with fitness. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Najarro MA, Hackett JL, Smith BR, Highfill CA, King EG, Long AD, et al. Identifying Loci Contributing to Natural Variation in Xenobiotic Resistance in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005663. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Long AD, Macdonald SJ, King EG. Dissecting complex traits using the Drosophila Synthetic Population Resource. Trends Genet. 2014;30:488–495. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2014.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mondal S, Hegarty E, Martin C, Gökçe SK, Ghorashian N, Ben-Yakar A. Large-scale microfluidics providing high-resolution and high-throughput screening of Caenorhabditis elegans poly-glutamine aggregation model. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13023. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paix A, Folkmann A, Rasoloson D, Seydoux G. High Efficiency, Homology-Directed Genome Editing in Caenorhabditis elegans Using CRISPR-Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein Complexes. Genetics. 2015;201:47–54. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.179382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gratz SJ, Rubinstein CD, Harrison MM, Wildonger J, O’Connor-Giles KM. CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing in Drosophila. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2015;111:31.2.1–20. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb3102s111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kislukhin G, Murphy ML, Jafari M, Long AD. Chemotherapy-induced toxicity is highly heritable in Drosophila melanogaster. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2012;22:285–289. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3283514395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rockman MV. THE QTN PROGRAM AND THE ALLELES THAT MATTER FOR EVOLUTION: ALL THAT’S GOLD DOES NOT GLITTER. Evolution. 2011;66:1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01486.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.King EG, Macdonald SJ, Long AD. Properties and power of the Drosophila Synthetic Population Resource for the routine dissection of complex traits. Genetics. 2012;191:935–949. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.138537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chow CY, Wolfner MF, Clark AG. Using natural variation in Drosophila to discover previously unknown endoplasmic reticulum stress genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:9013–9018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307125110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cannavò E, Koelling N, Harnett D, Garfield D, Casale FP, Ciglar L, et al. Genetic variants regulating expression levels and isoform diversity during embryogenesis. Nature. 2017;541:402–406. doi: 10.1038/nature20802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Catalán A, Glaser-Schmitt A, Argyridou E, Duchen P, Parsch J. An Indel Polymorphism in the MtnA 3’ Untranslated Region Is Associated with Gene Expression Variation and Local Adaptation in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1005987. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sosa V, Moliné T, Somoza R, Paciucci R, Kondoh H, LLeonart ME. Oxidative stress and cancer: an overview. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12:376–390. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pedersen MØ, Larsen A, Stoltenberg M, Penkowa M. The role of metallothionein in oncogenesis and cancer prognosis. Prog Histochem Cytochem. 2009;44:29–64. doi: 10.1016/j.proghi.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zdraljevic S, Strand C, Seidel HS, Cook DE, Doench JG, Andersen EC. Natural variation in a single amino acid underlies cellular responses to topoisomerase II poisons [Internet] bioRxiv. 2017:125567. doi: 10.1101/125567. The authors used a panel of recombinant inbred advanced intercross and wild strains of C. elegans to identify a single amino acid substitution that underlies differential susceptibility to various topoisomerase II poisons. Additionally, they showed that the effect of this substitution was conserved in human cell lines, thereby demonstrating the power of studying natural variation in model organisms to inform mechanisms of drug responses in humans. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Félix M-A, Barkoulas M. Pervasive robustness in biological systems. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16:483–496. doi: 10.1038/nrg3949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barkoulas M, Vargas Velazquez AM, Peluffo AE, Félix M-A. Evolution of New cis-Regulatory Motifs Required for Cell-Specific Gene Expression in Caenorhabditis. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1006278. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006278. The authors quantified the expression of the EGF-like ligand LIN-3 across two evolutionary distant species of nematodes, C. elegans and Oscheius tipulae. These results highlight the robustness of lin-3 expression to high levels of genetic variation among the two species. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schmid T, Snoek LB, Fröhli E, van der Bent ML, Kammenga J, Hajnal A. Systemic Regulation of RAS/MAPK Signaling by the Serotonin Metabolite 5-HIAA. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005236. The authors constructed a panel of recombinant inbred lines from two diverged C. elegans strains that both had a gain-of-function allele of the RAS homolog LET-60. This work is a powerful example of how sensitizing an essential signaling pathway can reveal the effects of genetic background. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rybaczyk LA, Bashaw MJ, Pathak DR, Huang K. An indicator of cancer: downregulation of monoamine oxidase-A in multiple organs and species. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:134. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Duveau F, Félix M-A. Role of pleiotropy in the evolution of a cryptic developmental variation in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:e1001230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Benson JA, Cummings EE, O’Reilly LP, Lee M-H, Pak SC. A high-content assay for identifying small molecules that reprogram C. elegans germ cell fate. Methods. 2014;68:529–535. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sonoshita M, Cagan RL. Chapter Nine - Modeling Human Cancers in Drosophila. In: Pick Leslie., editor. Current Topics in Developmental Biology. Academic Press; 2017. pp. 287–309. Available: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0070215316301491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Romei C, Ciampi R, Elisei R. A comprehensive overview of the role of the RET proto-oncogene in thyroid carcinoma. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12:192–202. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Levinson S, Cagan RL. Drosophila Cancer Models Identify Functional Differences between Ret Fusions. Cell Rep. 2016;16:3052–3061. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.019. The authors introduced two gain-of-function onco-fusions commonly found in papillary thyroid carcinoma into D. melanogaster. The severity of induced loss-of-viability caused by the two onco-fusions in D. melanogaster matched the prognosis of patients with cancers that contain these mutations. By defining the downstream pathways affected by these onco-fusions, the authors identified distinct combinations of therapeutics to suppress the induced loss-of-viability associated with these fusions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rudrapatna VA, Bangi E, Cagan RL. Caspase signalling in the absence of apoptosis drives Jnk-dependent invasion. EMBO Rep. 2013;14:172–177. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hirabayashi S, Cagan RL. Salt-inducible kinases mediate nutrient-sensing to link dietary sugar and tumorigenesis in Drosophila. Elife. 2015;4:e08501. doi: 10.7554/eLife.08501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bangi E, Murgia C, Teague AGS, Sansom OJ, Cagan RL. Functional exploration of colorectal cancer genomes using Drosophila. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13615. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kislukhin G, King EG, Walters KN, Macdonald SJ, Long AD. The genetic architecture of methotrexate toxicity is similar in Drosophila melanogaster and humans. G3. 2013;3:1301–1310. doi: 10.1534/g3.113.006619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]