Arabidopsis PHO1 modulates ABA-mediated seed germination and is a key target of transcription factor ABI5.

Abstract

The phytohormone abscisic acid (ABA) controls many developmental and physiological processes. Here, we report that PHOSPHATE1 (PHO1) participates in ABA-mediated seed germination and early seedling development. The transcription of PHO1 was obviously enhanced during seed germination and early seedling development and repressed by exogenous ABA. The pho1 mutants (pho1-2, pho1-4, and pho1-5) showed ABA-hypersensitive phenotypes, whereas the PHO1-overexpressing lines were ABA-insensitive during seed germination and early seedling development. The expression of PHO1 was repressed in the ABI5-overexpressing line and elevated in the abi5 mutant, and ABI5 can bind to the PHO1 promoter in vitro and in vivo, indicating that ABI5 directly down-regulated PHO1 expression. Disruption of PHO1 abolished the ABA-insensitive germination phenotypes of abi5 mutant, demonstrating that PHO1 was epistatic to ABI5. Together, these data demonstrate that PHO1 is involved in ABA-mediated seed germination and early seedling development and transcriptionally regulated by ABI5.

Abscisic acid (ABA) is a key phytohormone that modulates plant growth and development as well as abiotic and biotic stress responses (Verslues and Zhu, 2007). ABA accumulates in the developing embryo and regulates seed development, seed maturation, and seed dormancy (Verslues and Zhu, 2007). ABA functions through complex signaling networks, some components of which have been identified. The core components include ABA receptors PYR/PYL/RCAR, protein phosphatases PP2Cs, protein kinases SnRK2s, and various transcription factors (Hauser et al., 2011; Rushton et al., 2012).

The ABI5, a bZIP transcription factor, is a key regulator in the ABA signaling pathway (Finkelstein and Lynch, 2000; Yu et al., 2015). The expression of ABI5 is positively modulated by transcription factors ABI3 (Lopez-Molina et al., 2002) and HY5 (Chen et al., 2008); and down-regulated by WRKY40 (Shang et al., 2010), and RAV1 (Feng et al., 2014). ABI5 is also modulated at the posttranslational level. The kinases SnRK2.2 (Fujii et al., 2007; Piskurewicz et al., 2008), SnRK2.3 (Fujii et al., 2007; Piskurewicz et al., 2008), BIN2 (Hu and Yu, 2014), and PKS5 (Zhou et al., 2015) phosphorylate ABI5 to control ABI5 activity. In contrast, the phosphatases FyPP1 and FyPP3 dephosphorylate and destabilize ABI5 (Dai et al., 2013). Protein sumoylation and ubiquitination also modulate ABI5 protein activity. The SUMO E3 ligase, SIZ1, sumoylates ABI5 and represses ABI5 function (Miura et al., 2009); and the E3 ligases, KEG (Liu and Stone, 2010) and CUL4 (Lee et al., 2010), regulate ABI5 degradation.

As a transcription factor, ABI5 functions mainly through regulating the expressions of its target genes. ABI5 can up-regulate expressions of two Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) LEA (late embryogenesis abundant) genes, AtEm1 and AtEm6 (Carles et al., 2002), which encode ABA-inducible proteins that accumulate during seed maturation (Gaubier et al., 1993). ABI5 mediates the expressions of high-temperature-inducible genes, including SOMNUS (SOM) in response to high-temperature stress (Lim et al., 2013). In addition, ABI5 modulates early seed development by down-regulating the expression of SHORT HYPOCOTYLUNDER BLUE1 (SHB1; Cheng et al., 2014).

PHOSPHATE1 (PHO1) plays important roles in phosphate (Pi) homeostasis in Arabidopsis (Chiou and Lin, 2011). PHO1 contains two distinct domains: SPX and EXS (Wang et al., 2004). The SPX domain provides a basic binding surface for inositol polyphosphates (InsPs; Wild et al., 2016), and the EXS domain is essential for Pi export activity of PHO1 (Wege et al., 2016). PHO1 is mainly expressed in roots and functions in Pi transfer from roots to shoots (Poirier et al., 1991; Hamburger et al., 2002). In leaves, PHO1 mediates the stomatal response to ABA (Zimmerli et al., 2012).

In this study, we found that three pho1 mutants displayed ABA-hypersensitive germination phenotypes, and the PHO1-overexpressing lines were ABA insensitive. ABI5 can bind to the PHO1 promoter to down-regulate PHO1 expression, and disruption of PHO1 abolished the ABA-insensitive germination phenotypes of the abi5 mutant. Taken together, PHO1 is involved in ABA-mediated seed germination and early seedling development, and transcriptionally regulated by ABI5.

RESULTS

Disruption or Mutation of PHO1 Enhances, and Overexpression of PHO1 Reduces, ABA Sensitivity during Seed Germination and Early Seedling Development

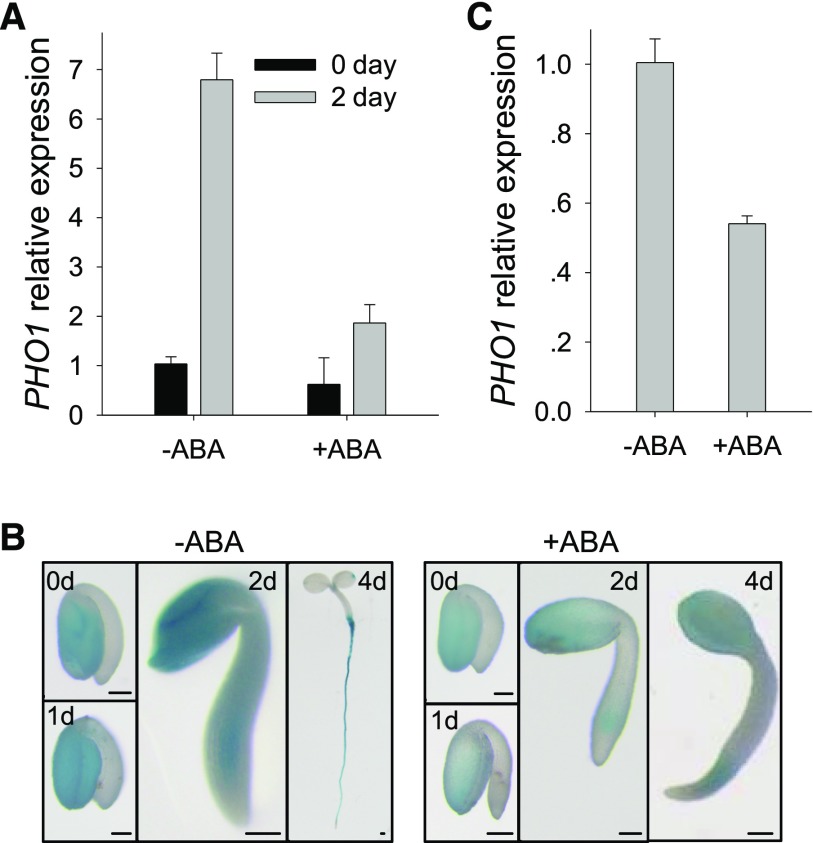

Arabidopsis PHO1 plays an important role in Pi translocation from roots to shoots (Poirier et al., 1991; Hamburger et al., 2002) and, consistent with the role of PHO1 in Pi transfer, PHO1 is mainly expressed in the root vascular system (Hamburger et al., 2002). From public microarray data, we found that the transcription level of PHO1 was relatively high in seeds and enhanced after imbibition. This led us to investigate whether PHO1 was involved in the ABA-mediated seed germination. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) results showed that the transcript level of PHO1 was elevated during seed germination and early seedling development, and this elevation was obviously repressed by exogenous ABA (Fig. 1A). The GUS staining of the ProPHO1:GUS line (Chen et al., 2009) showed that PHO1 expression was enhanced during seed germination and repressed by exogenous ABA (Fig. 1B). Similar to previous reports, PHO1 was mainly expressed in roots of seedlings (Fig. 1B; Hamburger et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2009); interestingly, in imbibed seeds and the early germination stage, PHO1 was mainly expressed in cotyledons (Fig. 1B). The transcriptional response of PHO1 to ABA was also tested at the same development stage. The imbibed wild-type seeds were germinated and grown on Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium for 1.5 d and then treated with or without exogenous ABA. As shown in Figure 1C, the transcript level of PHO1 was reduced when treated with exogenous ABA.

Figure 1.

Expression pattern of PHO1 during seed germination and early seedling development. A, qRT-PCR assay of PHO1 expression. Wild-type imbibed seeds were transferred to MS medium (-ABA) or MS medium supplemented with 0.5 μm ABA (+ABA) and then harvested at the indicated time for RNA extraction. Data are shown as mean ± se (n = 3). B, GUS-staining assay of ProPHO1:GUS line. The imbibed seeds were germinated on MS medium (-ABA) or MS medium supplemented with 0.5 μm ABA (+ABA) and then harvested at the indicated time for GUS staining. Bars = 100 μm. C, qRT-PCR assay of PHO1 expression. The imbibed wild-type seeds were germinated and grown on MS medium for 1.5 d and then treated with or without 20 μm ABA for 12 h. Data are shown as mean ± se (n = 3).

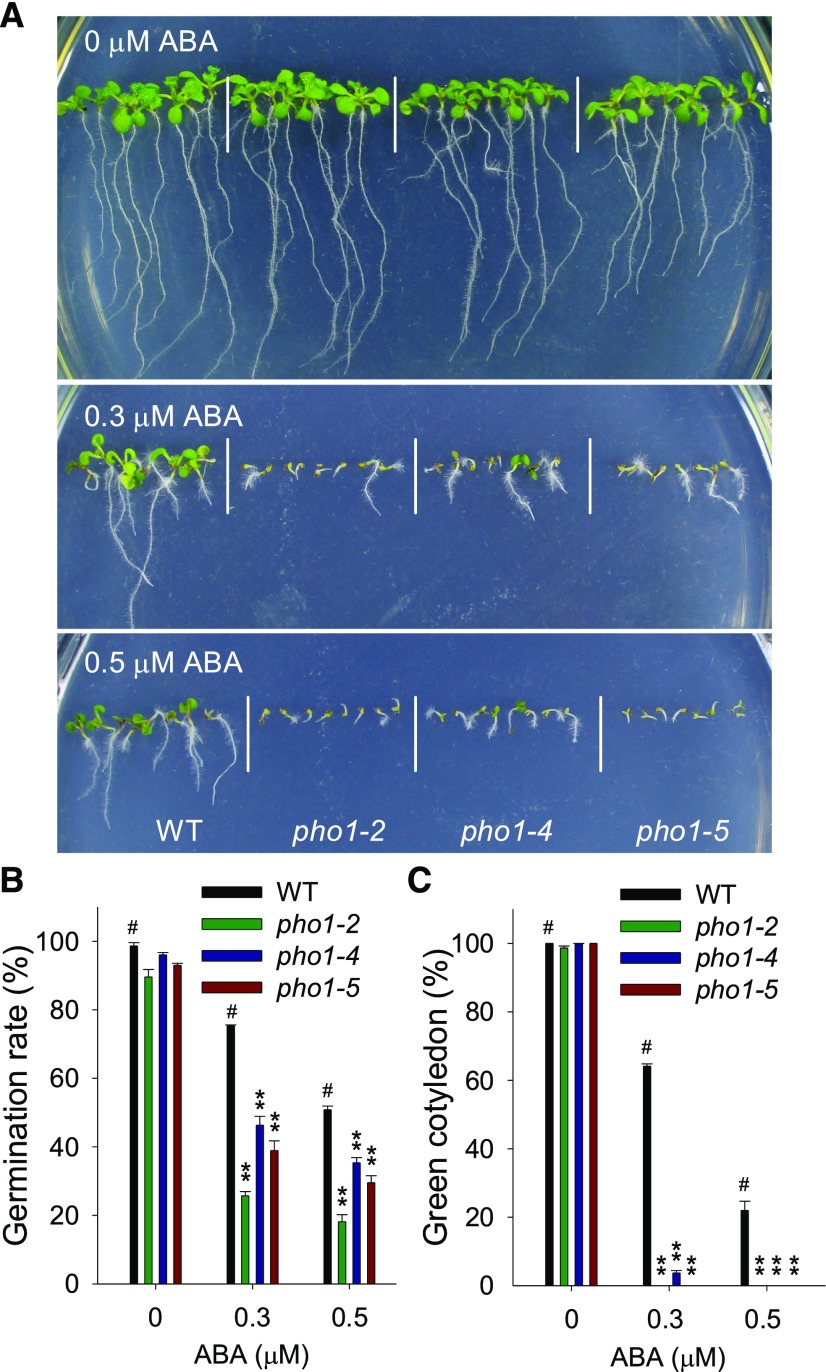

To determine the function of PHO1 in seed germination, three PHO1 alleles with point mutations were used in this study: pho1-2, pho1-4, and pho1-5 (Hamburger et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2012). Similar to previous reports, the aerial parts of pho1 mutants were much smaller than wild-type plants when grown in soil (Supplemental Fig. S1A; Hamburger et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2012). The phosphorus (P) contents of pho1 seeds were much lower than that of wild-type seeds (Poirier et al., 1991), and the pho1 mutants showed obviously reduced seed germination rates compared with wild-type plants (spray with water/-ABA; Supplemental Fig. S1B), indicating that the phosphorus deficiency in seeds repressed the seed germination. In order to enhance the seed P content, we supplemented leaves with high Pi. Each plant was foliar sprayed every 4 d with 600 μL of 1/8 MS solution containing 3 mm Pi, and all genotypes were foliar sprayed during the growth and grown in the same green house at the same time. The abi5 mutant and wild-type plants showed no obvious difference in plant growth and seed germination rate with or without foliar spraying of high Pi (Supplemental Figs. S1A and S1B), indicating that the foliar spray with high Pi did not cause additional secondary stress. Different from the abi5 mutant and wild-type plants, supplementing leaves with high external Pi helped the pho1 mutants to grow larger and healthier (Supplemental Fig. S1A). In addition, after foliar spray with high Pi, the seed P contents and seed germination rates of pho1 mutants were obviously enhanced, similar to those of abi5 mutant and wild-type plants (spray with Pi/-ABA; Supplemental Figs. S1B and S1C). Then the germination phenotypes were observed in the seeds that were harvested from the plants sprayed with high Pi. These three pho1 mutants were similar to wild-type plants when germinated and grown on MS medium (0 μm ABA; Fig. 2A); however, they showed ABA-hypersensitive phenotypes when germinated and grown on MS medium including 0.3 or 0.5 μm exogenous ABA (Fig. 2A). The germination rate and cotyledon-greening percentage were further tested. In the absence of ABA, the pho1 mutants showed no obvious difference with wild-type plants (Fig. 2, B and C; Supplemental Fig. S1B); when germinated and grown on MS medium containing 0.3 or 0.5 μm ABA, the pho1 mutants were germinated more slowly (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Fig. S1B) and displayed significantly reduced cotyledon-greening percentages (Fig. 2C) compared with wild-type plants. The seed germination phenotype of the PHO1-underexpressing line (B3; Supplemental Fig. S2A; Rouached et al., 2011) was also tested. There were no obvious differences between the B3 line and wild-type plants when germinated and grown on MS medium (0 μm ABA), whereas the B3 line, similar to the pho1 mutants, showed ABA-sensitive germination phenotypes under exogenous ABA (Supplemental Fig. S2B).

Figure 2.

The pho1 mutants are hypersensitive to exogenous ABA. A, Phenotypic comparison. Imbibed seeds were germinated and grown on MS medium with 0, 0.3, or 0.5 µm ABA for 10 d. B, Germination rate measurement. Imbibed seeds were transferred to MS medium with 0, 0.3, or 0.5 µm ABA for 3 d, and then the seed germination rates were calculated. Data are shown as mean ± se (n = 3). C, Cotyledon-greening analysis. Imbibed seeds were transferred to MS medium with 0, 0.3, or 0.5 µm ABA for 7 d before determining cotyledon-greening percentages. Data are shown as mean ± se (n = 3). Asterisks indicate significant differences compared with corresponding wild-type plants (#): **P < 0.01.

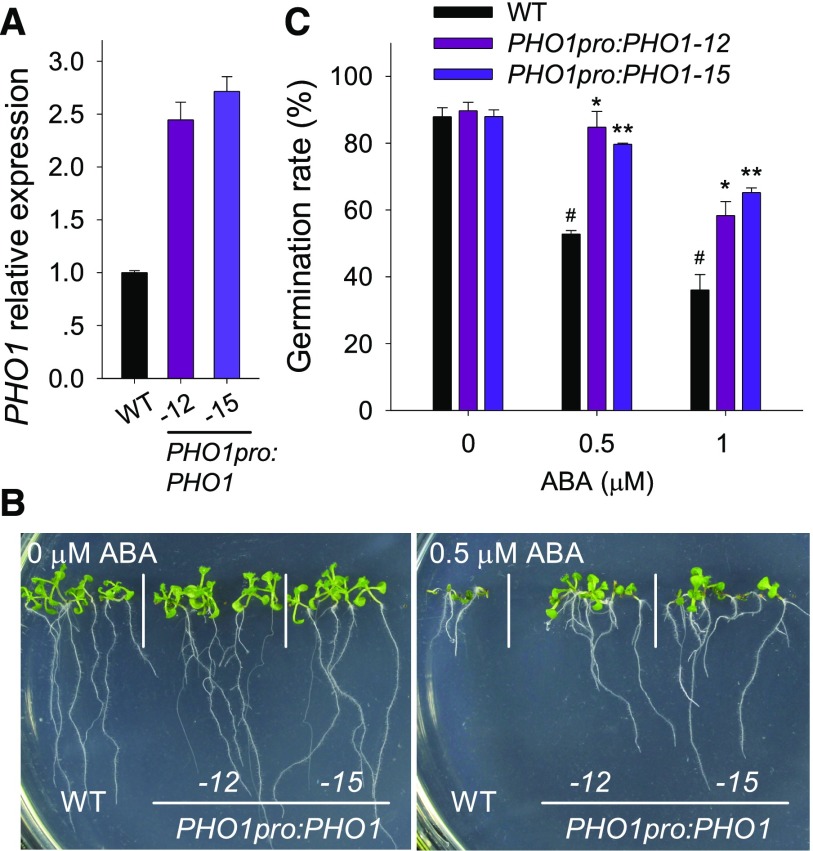

Two PHO1-overexpressing lines (PHO1pro:PHO1-12 and PHO1pro:PHO1-15), which had tissue-specific overexpression of PHO1 (Liu et al., 2012), were also used to study the physiological function of PHO1 in seed germination (Fig. 3A). When germinated and grown on MS medium without ABA (0 μm ABA), PHO1-overexpressing lines had no obvious difference with wild-type plants (Fig. 3, B and C). In the presence of ABA, the PHO1-overexpressing lines showed ABA-insensitive phenotypes and increased germination rates compared with wild-type plants (Fig. 3, B and C). Together, these data demonstrate that PHO1 is involved in ABA-mediated seed germination and early seedling development.

Figure 3.

The PHO1-overexpressing lines are insensitive to exogenous ABA during seed germination. A, qRT-PCR assay of PHO1 expression. The PHO1-overexpressing lines (PHO1pro:PHO1-12 and PHO1pro:PHO1-15) and wild-type plants were germinated and grown on MS medium for 1.5 d and then harvested for RNA extraction. Data are shown as mean ± se (n = 3). B, Phenotypic comparison. Imbibed seeds were germinated and grown on MS medium with 0 or 0.5 µm ABA for 10 d. C, Germination rate measurement. Imbibed seeds were transferred to MS medium with 0, 0.5, or 1 µm ABA for 3 d, and then the seed-germination rates were calculated. Data are shown as mean ± se (n = 3). Asterisks indicate significant differences compared with corresponding wild-type plants (#): *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

Transcription Factor ABI5 Directly Down-Regulates PHO1 Expression

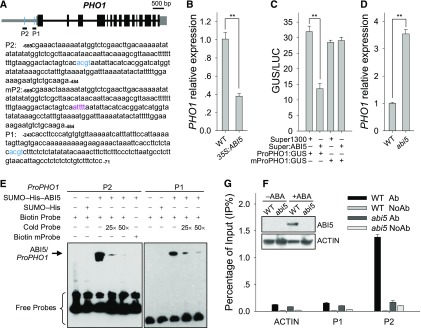

Promoter sequence analysis showed that there are two ACGT motifs within the PHO1 promoter (Fig. 4A). Previous reports showed that transcription factor ABI5 can bind to the ACGT motif in vitro (Carles et al., 2002) and that the abi5 mutant was extremely insensitive to exogenous ABA during seed germination and early seedling development (Piskurewicz et al., 2008). We hypothesized that transcription factor ABI5 negatively regulated PHO1 expression. The qRT-PCR results showed that the transcript level of PHO1 was significantly repressed in the ABI5-overexpressing line (35S:ABI5; Bu et al., 2009) relative to wild-type plants (Fig. 4B). Transient expression experiments in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves also showed that ABI5 repressed PHO1 promoter activity (Fig. 4C). In addition, PHO1 expression was significantly enhanced in the abi5 mutant in the presence of ABA (Fig. 4D). These data indicate that ABI5 negatively modulates PHO1 expression.

Figure 4.

ABI5 directly represses PHO1 expression. A, Schematic representation of PHO1 locus. The PHO1 putative promoter is indicated by a gray line showing the relative positions of the ACGT motifs (blue lines) and its transcribed sequence is indicated by black boxes (exons) and gray boxes (untranslated regions). The adenine (A) of the translational initiation codon ATG is assigned as position +1, and the numbers of PHO1 promoter fragments are counted based on this number. P1 and P2 indicate PCR fragments for EMSA and ChIP-qPCR experiments. And the normal and mutated ACGT motifs in the P1 and P2 fragments were indicated by blue and burgundy letters, separately. B, qRT-PCR analysis of PHO1 expression. The ABI5-overexpressing line (35S:ABI5) and wild-type plant were stratified at 4°C for 3 d and then harvested for RNA extraction. Data are shown as mean ± se (n = 3). C, Transient co-overexpression of Super:ABI5 and ProPHO1:GUS or mProPHO1:GUS in N. benthamiana leaves. Data are shown as mean ± se (n = 3). D, qRT-PCR analysis of PHO1 expression in the abi5 mutant and wild-type plants germinated and grown on MS medium with 0.5 μm ABA for 1.5 d. Asterisks in B to D indicate significant differences: **P < 0.01. E, EMSA of ABI5 binding to PHO1 promoter in vitro. F, Immunoblot analysis of ABI5 protein. The imbibed seeds were transferred to MS medium with or without 0.5 μm ABA for 1.5 d and then harvested for immunoblot analysis using anti-ABI5 antibody. ACTIN was used as the loading control. G, ChIP-qPCR assay of ABI5 binding to PHO1 promoter in vivo. The abi5 mutant and wild-type plant were germinated and grown on MS medium with 0.5 μm ABA for 1.5 d and then harvested for ChIP-qPCR assay using anti-ABI5 antibody. Data are shown as mean ± se (n = 3).

An EMSA was conducted to test whether ABI5 bound to PHO1 promoter. The ABI5 recombinant protein can bind to P1 and P2 fragments within the PHO1 promoter, and these bindings were effectively reduced by unlabeled competitors (Cold Probe; Fig. 4E). When the ACGT motif in the P2 fragment was mutated to TTTT (Fig. 4A), the ABI5 recombinant protein cannot bind to the mutated P2 fragment (Fig. 4E). These data indicate that ABI5 protein binds to PHO1 promoter in vitro. Consistent with previous report, the ABI5 protein was accumulated in wild-type plants under exogenous ABA treatment and was not detected in the abi5 mutant (Fig. 4F; Piskurewicz et al., 2008). Then a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiment was conducted in the abi5 mutant and wild-type plants under exogenous ABA treatment. The ChIP results showed that the chromatin immunoprecipitated with the anti-ABI5 antibody was enriched in the P2 fragment of the PHO1 promoter, and ABI5 enrichment in the P2 fragment was not detected in the abi5 mutant (Fig. 4G). The P1 fragment of the PHO1 promoter and the exon region of the ACTIN gene did not show any detectable binding by ABI5 (Fig. 4G). Then the mutated PHO1 promoter was generated by removing the ACGT motif within the P2 fragment and named mProPHO1 (Supplemental Fig. S3). The transient expression experiment in N. benthamiana leaves showed that the ABI5 could not regulate the activity of the mutated PHO1 promoter (Fig. 4C). These data demonstrate that transcription factor ABI5 down-regulates PHO1 expression by binding to the PHO1 promoter.

Disruption of PHO1 Abolishes ABA Insensitivity of abi5 Mutant during Seed Germination and Early Seedling Development

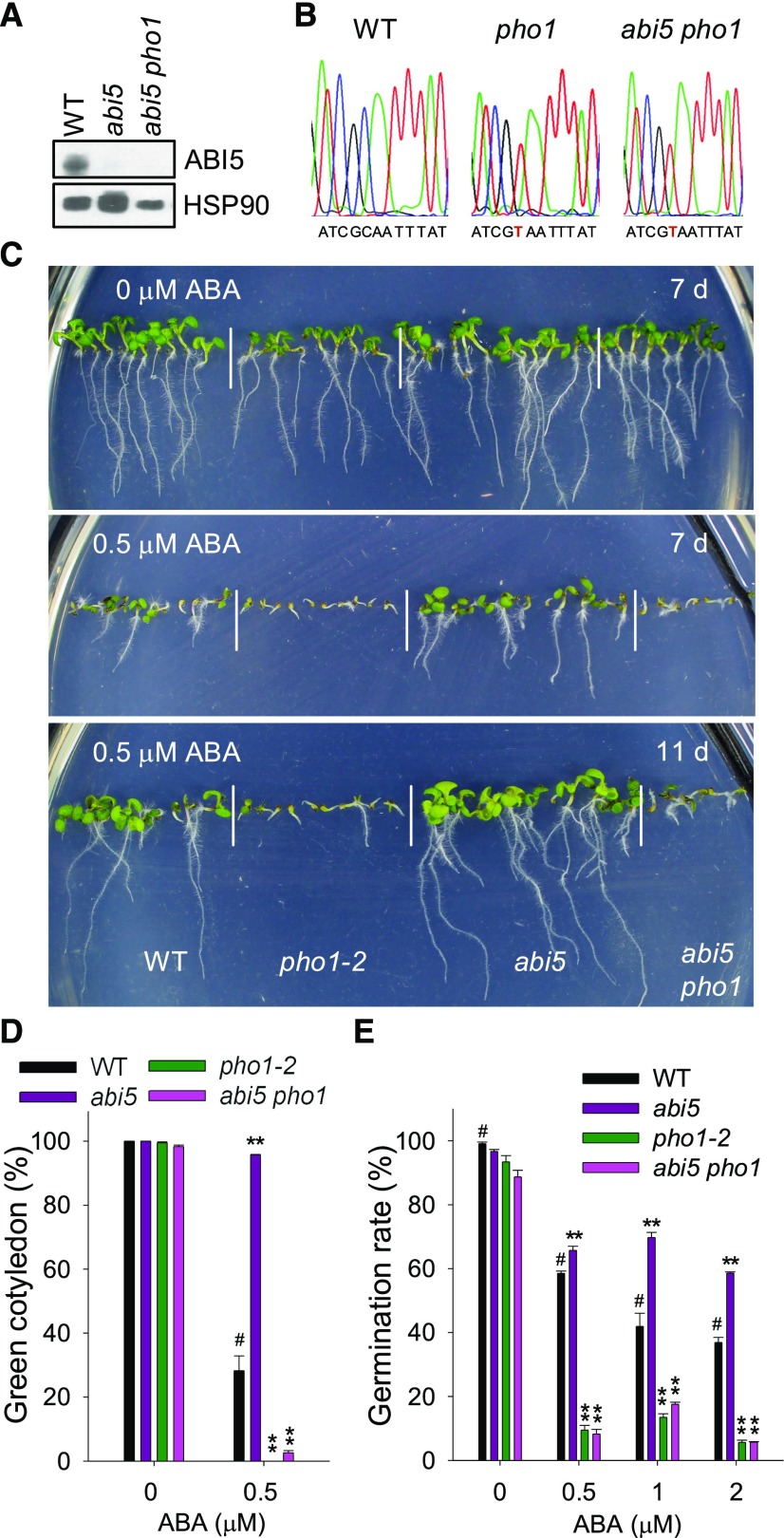

The genetic relationship between ABI5 and PHO1 was further analyzed by crossing pho1-2 with abi5 to produce the abi5 pho1 double mutant (Fig. 5, A and B). When germinated and grown on MS medium (0 μm ABA), all genotypes showed similar phenotypes (Fig. 5C). When germinated and grown on MS medium containing 0.5 μm ABA, the abi5 mutant showed ABA-insensitive phenotypes, whereas the abi5 pho1 double mutant was ABA hypersensitive, similar to the pho1-2 mutant (Fig. 5C). Consistent with the phenotypes, when germinated and grown on MS medium with 0.5 μm ABA added, the abi5 pho1 double mutant, similar to the pho1-2 mutant, had much lower cotyledon-greening percentages than wild-type plants, and the abi5 mutant had a higher cotyledon-greening percentage (Fig. 5D). In addition, in the presence of exogenous ABA, the abi5 pho1 double mutant, similar to the pho1-2 mutant, showed significantly slower and the abi5 mutant displayed increased germination rates compared with wild-type plants (Fig. 5E). These results demonstrate that PHO1 is epistatic to ABI5 in ABA-mediated seed germination and early seedling development.

Figure 5.

Disruption of PHO1 abolishes the ABA-insensitive phenotypes of abi5 mutant. A, Immunoblot analysis of ABI5 protein. The imbibed seeds were grown on MS medium supplemented with 5 μm ABA for 5 d and then harvested for immunoblot analysis. HSP90 was used as the loading control. B, The mutations in PHO1 gene in the pho1 mutant and abi5 pho1 double mutant were evaluated by sequencing. The mutation site in PHO1 is indicated by red letters. C, Phenotypic comparison. Imbibed seeds were germinated and grown on MS medium with 0 or 0.5 µm ABA for 10 d. D, Cotyledon-greening analysis. Imbibed seeds were germinated and grown on MS medium with 0 or 0.5 µm ABA for 7 d, and then the cotyledon-greening percentages were calculated. Data are shown as mean ± se (n = 3). E, Germination rate measurement. Imbibed seeds were transferred to MS medium with 0, 0.5, 1, or 2 μm ABA for 3 d, and then the seed germination rates were calculated. Data are shown as mean ± se (n = 3). Asterisks indicate significant differences compared with corresponding wild-type plants (#): **P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

PHO1 Is an Important Target of ABI5 in Modulating Seed Germination and Early Seedling Development

The transcription factor ABI5 is an important regulator in the ABA signaling pathway. ABI5 confers enhanced responses to exogenous ABA during seed germination: the abi5 mutant shows obvious ABA-insensitive phenotypes (Piskurewicz et al., 2008), whereas ABI5-overexpressing lines are ABA sensitive (Piskurewicz et al., 2008; Bu et al., 2009). As a transcription factor, ABI5 modulates seed germination mainly through regulating the expressions of its target genes. Two Arabidopsis LEA genes, AtEm1 and AtEm6, were reported to be target genes of ABI5 (Carles et al., 2002). The expressions of AtEm1 and AtEm6 are decreased in the abi5 mutant (Carles et al., 2002; Feng et al., 2014), and ABI5 can bind to the promoters of AtEm1 and AtEm6 in vitro (Carles et al., 2002) and to the AtEm6 promoter in vivo (Lopez-Molina et al., 2002), demonstrating that ABI5 directly regulates the expressions of AtEm1 and AtEm6. The atem6-1 mutant shows premature seed dehydration and maturation at the distal end of siliques (Manfre et al., 2006). A later report demonstrated that ABI5 could activate SOM expression at high temperature (Lim et al., 2013). The som mutants show higher germination rates than wild-type plants at high temperature (Lim et al., 2013). Recently, ABI5 was reported to directly down-regulate SHB1 expression to modulate early seed development (Cheng et al., 2014).

Although several target genes of ABI5 have been reported, the mutants of these target genes did not show ABA-dependent germination phenotypes. In this study, the PHO1 expression was enhanced during seed germination, and this enhancement was repressed by exogenous ABA (Fig. 1), suggesting that PHO1 was regulated at the transcriptional level during seed germination. The pho1 mutants and PHO1-underexpressing line showed ABA-hypersensitive phenotypes, whereas the PHO1-overexpressing lines were ABA insensitive during seed germination and early seedling development (Figs. 2 and 3; Supplemental Fig. S2), and ABI5 can bind to PHO1 promoter to repress PHO1 expression (Fig. 4). More importantly, disruption of PHO1 can rescue the ABA-insensitive germination phenotypes of abi5 mutant (Fig. 5). These data demonstrate that PHO1 is a key target of ABI5 functioning in ABA-mediated seed germination.

Both SHB1 and PHO1 contain SPX and EXS domains (Wang et al., 2004; Kang and Ni, 2006) and belong to the PHO1 family (Wang et al., 2004; Secco et al., 2012). The Arabidopsis PHO1 family contains 11 members, named PHO1 and PHO1;H1-PHO1;H10 (Wang et al., 2004; Secco et al., 2012), with PHO1;H4 also named SHB1 (Secco et al., 2012). The expression of SHB1 was also repressed by exogenous ABA (Cheng et al., 2014). The transcript level of SHB1 was reduced in the ABI5-overexpressing line, and ABI5 can bind to the ACGT motif within the SHB1 promoter (Cheng et al., 2014), indicating that SHB1 was a target of ABI5. Although both PHO1 and SHB1 belonged to the PHO1 family and were transcriptionally regulated by the transcription factor ABI5, the functions of PHO1 and SHBI were different. SHB1 could mediate early seed development, and the shb1 mutant displayed smaller seed size compared with wild-type seeds (Cheng et al., 2014). Whereas the pho1 mutants showed ABA-dependent germination phenotypes (Fig. 2) and could rescue the ABA-insensitive germination phenotypes of abi5 mutant (Fig. 5), indicating that transcription factor ABI5 mediated ABA-dependent seed germination, at least mostly, through regulating the PHO1 expression.

PHO1 Plays Important Roles in Pi Homeostasis and ABA Signaling

The pho1 mutant was first reported to be deficient in Pi transfer from roots to shoots, with less shoot Pi content and reduced shoot growth (Poirier et al., 1991). PHO1 is expressed in the root vascular system and hypocotyl of Arabidopsis seedlings (Hamburger et al., 2002), consistent with its role in Pi translocation from roots to shoots. In addition to Pi transfer from roots to shoots, ectopic expression of PHO1 in leaves also mediates Pi efflux out of leaf cells (Stefanovic et al., 2011; Arpat et al., 2012). Arabidopsis is a dicotyledonous plant, and the major food reserves are typically stored in the cotyledons. The massive mobilization of reserves that occurs after germination provides nutrients to the growing seedling. Different from the seedling stage, PHO1 was mainly expressed in cotyledons during seed germination (Fig. 1B), suggesting that PHO1 might modulate Pi transfer from cotyledons to radicles, which benefitted the growth of radicle through seed coat. Phytin is the K+, Mg2+, and Ca2+ salt of phytic acid (inositol hexaphophate), and about two-thirds of phosphorus in cereal and legume seeds is stored in the form of phytin (Dwivedi et al., 2017). Phytin is hydrolyzed by enzyme phytase to release phosphate for the growing seedling (Taiz et al., 2015), and in plants, the InsPs were high-abundance phosphate storage compounds in seeds (Raboy, 2003). Previous reports show that the PHO1 protein contains an SPX domain (Wang et al., 2004), which is a sensor domain of InsPs (Wild et al., 2016). In addition, PHO1 is localized in the Golgi/trans-Golgi network and vesicles (Arpat et al., 2012), suggesting that PHO1 may participate in the mobilization of Pi from the phytate store during seed germination.

During seedling stage, PHO1 is also expressed in guard cells (Zimmerli et al., 2012). PHO1 expression in guard cells is increased after exogenous ABA treatment, and ABA-mediated stomatal movement is severely impaired in pho1 mutants (Zimmerli et al., 2012), indicating that PHO1 participates in the ABA signal pathway. Interestingly, the expression of PHO1 in wild-type seedlings is repressed by exogenous ABA under Pi-sufficient conditions, and ABA addition abolishes the increase of PHO1 expression in Pi-deficient wild-type seedlings (Ribot et al., 2008), suggesting a cross talk between ABA and Pi-starvation signaling. In this present study, the pho1 mutants showed ABA-hypersensitive germination phenotypes, whereas the PHO1-overexpressing lines were ABA insensitive (Figs. 2 and 3). Previous reports showed that the InsPs played potential roles in hormone signaling, such as auxin (Tan et al., 2007) and jasmonate (Sheard et al., 2010; Mosblech et al., 2011). PHO1 interacted with InsPs (Wild et al., 2016) and was involved in the ABA signaling pathway in seed germination (Figs. 2 and 3) as well as in guard cells (Zimmerli et al., 2012). The implication of InsP in ABA signaling has been shown by FIERY1/SAL1 (Xiong et al., 2001; Wilson et al., 2009). Consequently, it is possible that PHO1 participates in the ABA signal transduction during seed germination via its interaction with InsP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

The wild-type plant used in this study was Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) Col-0. The pho1-2 (Hamburger et al., 2002), pho1-4 (Hamburger et al., 2002), pho1-5 (Liu et al., 2012), and abi5 (Feng et al., 2014) mutants and PHO1-overexpressing (PHO1pro:PHO1-12 and PHO1pro:PHO1-15; Liu et al., 2012), ABI5-overexpressing (35S:ABI5) (Bu et al., 2009), and ProPHO1:GUS (Chen et al., 2009) lines were described previously.

The phenotype comparison assays were conducted as previously described (Feng et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2016). For seed harvest, Arabidopsis plants were grown at 22°C for a 16-h daily light period in a potting soil mixture (rich soil:vermiculite = 2:1, v/v). Each plant was foliar sprayed every 4 d with 600 μL of 1/8 MS solution containing 3 mm Pi. All genotypes were foliar sprayed during growth and grown in the same green house. The germination experiments were performed with the seeds of different genotypes that were grown together at the same time and under the same environmental conditions. The relative humidity was approximately 70% (±5%).

Determination of Germination Rate and Green Cotyledon

The imbibed seeds were germinated and grown on MS medium supplemented with 0, 0.3, or 0.5 µM ABA, and then the germination rate and green cotyledon were measured on the third day and seventh day, separately. Germination rate was measured based on the emergence of the radicle through seed coat, as observed under a microscope. Green cotyledon was determined based on the appearance of green cotyledons in a seedling. More than 100 seeds were measured in each replicate. Each experiment was conducted in three biological replicates, and similar results were obtained.

qRT-PCR Assay and GUS Staining

The total RNA of seedlings and seeds was extracted with RNeasy Plant Mini kit (Bioteke), and treated with DNase I (Takara) to eliminate genomic DNA contamination. The qRT-PCR assay was conducted as described previously (Feng et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2016). Actin2/8 expression was used as an internal control. The primers used are listed in Supplemental Table S1. Each experiment was done in three biological replicates.

GUS staining experiment was performed as previously described (Chen et al., 2009).

Transient Expression Assay in Nicotiana benthamiana

The coding sequence of ABI5 was cloned into vector Super1300 (Chen et al., 2009) to form a Super:ABI5 construct. The primers used are listed in Supplemental Table S1. The construct ProPHO1:GUS was described previously (Chen et al., 2009). The ProPHO1:GUS and Super:ABI5 were singly or cotransformed into N. benthamiana leaves. For each infiltration sample, Super:LUC was added as an internal control. The GUS and LUC activities of infiltrated leaves were quantitatively determined, and the GUS/LUC ratio was used to quantify promoter activity.

Protein Expression and EMSA Experiment

The coding sequence of ABI5 was cloned into pET28a-SUMO vector (Novagen). The primers used are listed in Supplemental Table S1. The recombinant plasmid and pET28a-SUMO were introduced into Escherichia coli strain BL21 separately, and the SUMO-His-ABI5 and SUMO-His proteins were purified using Ni-Sepharose 6 Fast Flow (GE Healthcare).

The EMSA was conducted as described previously (Huang et al., 2016). The fragments of PHO1 promoter (P1 and P2) were obtained by PCR using biotin-labeled or -unlabeled primers (see Supplemental Table S1). Biotin-unlabeled fragments (cold-probe) of the same sequences were used as competitors.

ChIP-qPCR Assay

The abi5 mutant and wild-type Arabidopsis were germinated and grown on MS medium with 0.5 μm ABA for 1.5 d and then harvested for ChIP experiment. The ChIP experiment was performed as described previously (Chen et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2016), and the primers used are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) under the following accession numbers: PHO1 (At3g23430), ABI5 (At2g36270), ACT2 (At3g18780), and ACT8 (At1g49240).

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. The characterization of Arabidopsis plants sprayed with external Pi.

Supplemental Figure S2. Germination phenotype of PHO1-underexpressing line.

Supplemental Figure S3. Sequences of normal and mutated PHO1 promoters.

Supplemental Table S1. Primer sequences used in this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yves Poirier for providing the pho1-2 mutant and PHO1-underexpressing line B3, Dr. Tzyy-Jen Chiou for providing the pho1-4 mutant, pho1-5 mutant, and PHO1-overexpressing lines, and Dr. Chuan-you Li for providing the ABI5-overexpressing line.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Agriculture of China for transgenic research (no. 2016ZX08009002 to Y.-F.C.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 31670245 to Y.-F.C. and no. 31421062 to W.-H.W.), and the ‘111’ Project of China (no. B06003 to W.-H.W.).

References

- Arpat AB, Magliano P, Wege S, Rouached H, Stefanovic A, Poirier Y (2012) Functional expression of PHO1 to the Golgi and trans-Golgi network and its role in export of inorganic phosphate. Plant J 71: 479–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu Q, Li H, Zhao Q, Jiang H, Zhai Q, Zhang J, Wu X, Sun J, Xie Q, Wang D, et al. (2009) The Arabidopsis RING finger E3 ligase RHA2a is a novel positive regulator of abscisic acid signaling during seed germination and early seedling development. Plant Physiol 150: 463–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carles C, Bies-Etheve N, Aspart L, Léon-Kloosterziel KM, Koornneef M, Echeverria M, Delseny M (2002) Regulation of Arabidopsis thaliana Em genes: role of ABI5. Plant J 30: 373–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YF, Li LQ, Xu Q, Kong YH, Wang H, Wu WH (2009) The WRKY6 transcription factor modulates PHOSPHATE1 expression in response to low Pi stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21: 3554–3566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Zhang J, Neff MM, Hong SW, Zhang H, Deng XW, Xiong L (2008) Integration of light and abscisic acid signaling during seed germination and early seedling development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 4495–4500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng ZJ, Zhao XY, Shao XX, Wang F, Zhou C, Liu YG, Zhang Y, Zhang XS (2014) Abscisic acid regulates early seed development in Arabidopsis by ABI5-mediated transcription of SHORT HYPOCOTYL UNDER BLUE1. Plant Cell 26: 1053–1068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou TJ, Lin SI (2011) Signaling network in sensing phosphate availability in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 62: 185–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai M, Xue Q, Mccray T, Margavage K, Chen F, Lee JH, Nezames CD, Guo L, Terzaghi W, Wan J, et al. (2013) The PP6 phosphatase regulates ABI5 phosphorylation and abscisic acid signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25: 517–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi V, Parida SK, Chattopadhyay D (2017) A repeat length variation in myo-inositol monophosphatase gene contributes to seed size trait in chickpea. Sci Rep 7: 4764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng CZ, Chen Y, Wang C, Kong YH, Wu WH, Chen YF (2014) Arabidopsis RAV1 transcription factor, phosphorylated by SnRK2 kinases, regulates the expression of ABI3, ABI4, and ABI5 during seed germination and early seedling development. Plant J 80: 654–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein RR, Lynch TJ (2000) The Arabidopsis abscisic acid response gene ABI5 encodes a basic leucine zipper transcription factor. Plant Cell 12: 599–609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii H, Verslues PE, Zhu JK (2007) Identification of two protein kinases required for abscisic acid regulation of seed germination, root growth, and gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19: 485–494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaubier P, Raynal M, Hull G, Huestis GM, Grellet F, Arenas C, Pagès M, Delseny M (1993) Two different Em-like genes are expressed in Arabidopsis thaliana seeds during maturation. Mol Gen Genet 238: 409–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger D, Rezzonico E, MacDonald-Comber Petétot J, Somerville C, Poirier Y (2002) Identification and characterization of the Arabidopsis PHO1 gene involved in phosphate loading to the xylem. Plant Cell 14: 889–902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser F, Waadt R, Schroeder JI (2011) Evolution of abscisic acid synthesis and signaling mechanisms. Curr Biol 21: R346–R355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Yu D (2014) BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE2 interacts with ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE5 to mediate the antagonism of brassinosteroids to abscisic acid during seed germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26: 4394–4408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Feng CZ, Ye Q, Wu WH, Chen YF (2016) Arabidopsis WRKY6 transcription factor acts as a positive regulator of abscisic acid signaling during seed germination and early seedling development. PLoS Genet 12: e1005833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang X, Ni M (2006) Arabidopsis SHORT HYPOCOTYL UNDER BLUE1 contains SPX and EXS domains and acts in cryptochrome signaling. Plant Cell 18: 921–934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Yoon HJ, Terzaghi W, Martinez C, Dai M, Li J, Byun MO, Deng XW (2010) DWA1 and DWA2, two Arabidopsis DWD protein components of CUL4-based E3 ligases, act together as negative regulators in ABA signal transduction. Plant Cell 22: 1716–1732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S, Park J, Lee N, Jeong J, Toh S, Watanabe A, Kim J, Kang H, Kim DH, Kawakami N, et al. (2013) ABA-insensitive3, ABA-insensitive5, and DELLAs interact to activate the expression of SOMNUS and other high-temperature-inducible genes in imbibed seeds in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25: 4863–4878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu TY, Huang TK, Tseng CY, Lai YS, Lin SI, Lin WY, Chen JW, Chiou TJ (2012) PHO2-dependent degradation of PHO1 modulates phosphate homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24: 2168–2183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Stone SL (2010) Abscisic acid increases Arabidopsis ABI5 transcription factor levels by promoting KEG E3 ligase self-ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. Plant Cell 22: 2630–2641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Molina L, Mongrand S, McLachlin DT, Chait BT, Chua NH (2002) ABI5 acts downstream of ABI3 to execute an ABA-dependent growth arrest during germination. Plant J 32: 317–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfre AJ, Lanni LM, Marcotte WR Jr (2006) The Arabidopsis group 1 LATE EMBRYOGENESIS ABUNDANT protein ATEM6 is required for normal seed development. Plant Physiol 140: 140–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura K, Lee J, Jin JB, Yoo CY, Miura T, Hasegawa PM (2009) Sumoylation of ABI5 by the Arabidopsis SUMO E3 ligase SIZ1 negatively regulates abscisic acid signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 5418–5423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosblech A, Thurow C, Gatz C, Feussner I, Heilmann I (2011) Jasmonic acid perception by COI1 involves inositol polyphosphates in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 65: 949–957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piskurewicz U, Jikumaru Y, Kinoshita N, Nambara E, Kamiya Y, Lopez-Molina L (2008) The gibberellic acid signaling repressor RGL2 inhibits Arabidopsis seed germination by stimulating abscisic acid synthesis and ABI5 activity. Plant Cell 20: 2729–2745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirier Y, Thoma S, Somerville C, Schiefelbein J (1991) Mutant of Arabidopsis deficient in xylem loading of phosphate. Plant Physiol 97: 1087–1093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raboy V. (2003) myo-Inositol-1,2,3,4,5,6-hexakisphosphate. Phytochemistry 64: 1033–1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribot C, Wang Y, Poirier Y (2008) Expression analyses of three members of the AtPHO1 family reveal differential interactions between signaling pathways involved in phosphate deficiency and the responses to auxin, cytokinin, and abscisic acid. Planta 227: 1025–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouached H, Stefanovic A, Secco D, Bulak Arpat A, Gout E, Bligny R, Poirier Y (2011) Uncoupling phosphate deficiency from its major effects on growth and transcriptome via PHO1 expression in Arabidopsis. Plant J 65: 557–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton DL, Tripathi P, Rabara RC, Lin J, Ringler P, Boken AK, Langum TJ, Smidt L, Boomsma DD, Emme NJ, et al. (2012) WRKY transcription factors: key components in abscisic acid signalling. Plant Biotechnol J 10: 2–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secco D, Wang C, Arpat BA, Wang Z, Poirier Y, Tyerman SD, Wu P, Shou H, Whelan J (2012) The emerging importance of the SPX domain-containing proteins in phosphate homeostasis. New Phytol 193: 842–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y, Yan L, Liu ZQ, Cao Z, Mei C, Xin Q, Wu FQ, Wang XF, Du SY, Jiang T, et al. (2010) The Mg-chelatase H subunit of Arabidopsis antagonizes a group of WRKY transcription repressors to relieve ABA-responsive genes of inhibition. Plant Cell 22: 1909–1935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheard LB, Tan X, Mao H, Withers J, Ben-Nissan G, Hinds TR, Kobayashi Y, Hsu FF, Sharon M, Browse J, et al. (2010) Jasmonate perception by inositol-phosphate-potentiated COI1-JAZ co-receptor. Nature 468: 400–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanovic A, Arpat AB, Bligny R, Gout E, Vidoudez C, Bensimon M, Poirier Y (2011) Over-expression of PHO1 in Arabidopsis leaves reveals its role in mediating phosphate efflux. Plant J 66: 689–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taiz L, Zeiger E, Møller IM, Murphy A (2015) Plant Physiology and Development. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA [Google Scholar]

- Tan X, Calderon-Villalobos LI, Sharon M, Zheng C, Robinson CV, Estelle M, Zheng N (2007) Mechanism of auxin perception by the TIR1 ubiquitin ligase. Nature 446: 640–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verslues PE, Zhu JK (2007) New developments in abscisic acid perception and metabolism. Curr Opin Plant Biol 10: 447–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Ribot C, Rezzonico E, Poirier Y (2004) Structure and expression profile of the Arabidopsis PHO1 gene family indicates a broad role in inorganic phosphate homeostasis. Plant Physiol 135: 400–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wege S, Khan GA, Jung JY, Vogiatzaki E, Pradervand S, Aller I, Meyer AJ, Poirier Y (2016) The EXS domain of PHO1 participates in the response of shoots to phosphate deficiency via a root-to-shoot signal. Plant Physiol 170: 385–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild R, Gerasimaite R, Jung JY, Truffault V, Pavlovic I, Schmidt A, Saiardi A, Jessen HJ, Poirier Y, Hothorn M, et al. (2016) Control of eukaryotic phosphate homeostasis by inositol polyphosphate sensor domains. Science 352: 986–990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PB, Estavillo GM, Field KJ, Pornsiriwong W, Carroll AJ, Howell KA, Woo NS, Lake JA, Smith SM, Harvey Millar A, et al. (2009) The nucleotidase/phosphatase SAL1 is a negative regulator of drought tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant J 58: 299–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong L, Lee Bh, Ishitani M, Lee H, Zhang C, Zhu JK (2001) FIERY1 encoding an inositol polyphosphate 1-phosphatase is a negative regulator of abscisic acid and stress signaling in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev 15: 1971–1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F, Wu Y, Xie Q (2015) Precise protein post-translational modifications modulate ABI5 activity. Trends Plant Sci 20: 569–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Hao H, Zhang Y, Bai Y, Zhu W, Qin Y, Yuan F, Zhao F, Wang M, Hu J, et al. (2015) SOS2-LIKE PROTEIN KINASE5, an SNF1-RELATED PROTEIN KINASE3-type protein kinase, is important for abscisic acid responses in Arabidopsis through phosphorylation of ABSCISIC ACID-INSENSITIVE5. Plant Physiol 168: 659–676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerli C, Ribot C, Vavasseur A, Bauer H, Hedrich R, Poirier Y (2012) PHO1 expression in guard cells mediates the stomatal response to abscisic acid in Arabidopsis. Plant J 72: 199–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]