Maize violaxanthin deepoxidase interacts with the HC-Pro protein of Sugarcane mosaic virus to attenuate its RNA-silencing suppression activity, contributing to decreased viral accumulation.

Abstract

RNA silencing plays a critical role against viral infection. To counteract this antiviral silencing, viruses have evolved various RNA silencing suppressors. Meanwhile, plants have evolved counter-counter defense strategies against RNA silencing suppression (RSS). In this study, the violaxanthin deepoxidase protein of maize (Zea mays), ZmVDE, was shown to interact specifically with the helper component-proteinase (HC-Pro; a viral RNA silencing suppressor) of Sugarcane mosaic virus (SCMV) via its mature protein region by yeast two-hybrid assay, which was confirmed by coimmunoprecipitation in Nicotiana benthamiana cells. It was demonstrated that amino acids 101 to 460 in HC-Pro and the amino acid glutamine-292 in ZmVDE mature protein were essential for this interaction. The mRNA levels of ZmVDE were down-regulated 75% to 65% at an early stage of SCMV infection. Interestingly, ZmVDE, which normally localized in the chloroplasts and cytoplasm, could relocalize to HC-Pro-containing aggregate bodies in the presence of HC-Pro alone or SCMV infection. In addition, ZmVDE could attenuate the RSS activity of HC-Pro in a specific protein interaction-dependent manner. Subsequently, transient silencing of the ZmVDE gene facilitated SCMV RNA and coat protein accumulation. Taken together, our results suggest that ZmVDE interacts with SCMV HC-Pro and attenuates its RSS activity, contributing to decreased SCMV accumulation. This study demonstrates that a host factor can be involved in secondary defense responses against viral infection in monocot plants.

The molecular arms race between a virus and its host can be regarded as an analogous zigzag model (Mandadi and Scholthof, 2013; Nakahara and Masuta, 2014). Viral double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) produced during virus replication can be considered as virus-associated molecular patterns (Niehl et al., 2016) that induce antiviral RNA silencing (pattern-triggered immunity) against viruses. However, successful viruses have consequently evolved viral suppressors of RNA silencing (VSRs) as effectors to overcome RNA silencing; meanwhile, plants have evolved defense strategies against RNA silencing suppression (RSS), which is regarded as analogous to effector-triggered immunity (Nakahara and Masuta, 2014). Although the zigzag model in plant-virus interactions is different from the standard zigzag model, plants have evolved a battery of secondary defense strategies to respond to perturbation of the silencing pathways caused by viral infection (Incarbone and Dunoyer, 2013; Pumplin and Voinnet, 2013; Nakahara and Masuta, 2014). However, the specific defenses against RSS in plants are not well characterized, and the host factors involved in counteracting RSS caused by VSRs need to be identified.

Potyviral helper component-proteinase (HC-Pro) is a multifunctional protein mainly involved in aphid transmission (Govier and Kassanis, 1974), polyprotein processing (Carrington et al., 1989), suppression of posttranscriptional gene silencing (Anandalakshmi et al., 1998; Kasschau and Carrington, 1998), and contribution to the enhancement of viral particle production (Valli et al., 2014). HC-Pro also participates in symptom development, genome replication, and virus movement (Maia et al., 1996; Syller, 2006), whereas these capacities should be derived from its ability to suppress RNA silencing (Kasschau and Carrington, 2001; Díaz-Pendón and Ding, 2008). Furthermore, HC-Pros from different viruses have been reported to interact with various host factors and affect their functions, such as the ubiquitin/26S proteasome system (Ballut et al., 2005), the chloroplast precursor of ferredoxin-5 (Cheng et al., 2008), and chloroplast protein 1-deoxy-d-xylulose-5-phosphate synthase (Li et al., 2015).

HC-Pro can be considered as a local VSR that targets intracellular antiviral silencing in single cells (Qi et al., 2004) and fails to block the production or transmission of the silencing signal (Mallory et al., 2001, 2003). To date, the molecular mechanism underlying this ability is not well understood. One hypothesis is that HC-Pro can specifically bind/sequester small RNA duplexes (Lakatos et al., 2006; Mérai et al., 2006), and a possible alternative or complementary mechanism is that HC-Pro inhibits the small RNA methylation (Yu et al., 2006; Jamous et al., 2011; Ivanov et al., 2016). Recently, HC-Pro was reported to participate in ribosome-associated multiprotein complexes to relieve viral RNA translational repression through interacting with Argonaute1 (Ivanov et al., 2016). In addition, host factors such as transcription factor RAV2 (Endres et al., 2010) and S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase (Cañizares et al., 2013) have been demonstrated to mediate HC-Pro silencing suppressor activity.

Previous studies indicate that plants have evolved counter-counter defense strategies against RSS (Li et al., 1999). In many cases, R proteins interact with VSRs that also act as Avr factors, leading to the activation of defense responses (Cooley et al., 2000; de Ronde et al., 2013; Wen et al., 2013; Boualem et al., 2016). Intriguingly, some host factors involved in counter-counter defense against VSRs have been identified. DRB4, a dsRNA-binding protein contributing to RNA silencing, is required for the Arabidopsis R protein (hypersensitive response to Turnip crinkle virus)-mediated resistance against the coat protein (CP), a VSR of Turnip crinkle virus (Zhu et al., 2013). The calmodulin-like protein rgs-CaM, first reported as an endogenous RNA silencing suppressor (Anandalakshmi et al., 2000), was identified as an antiviral host factor that could attenuate the RSS activity of VSRs through binding to their dsRNA-binding domains and targeting them for autophagic degradation (Nakahara et al., 2012; Tadamura et al., 2012).

Sugarcane mosaic virus (SCMV) causes severe dwarf mosaic disease in maize (Zea mays), sugarcane (Saccharum sinensis), and sorghum (Sorghum vulgare; Xiao et al., 1993). It is known as a major viral pathogen of maize in China, and the Beijing isolate (SCMV-BJ) belongs to a prevalent strain of SCMV in China (Fan et al., 2003). Furthermore, it has been reported that the replication of SCMV is regulated by host RNA silencing machinery, and SCMV HC-Pro also is a VSR (Zhang et al., 2008).

Violaxanthin deepoxidase (VDE), a nucleus-encoded chloroplast protein, is translated as a precursor protein in the cytoplasm and ultimately transported into the thylakoid lumen after cleavage of its transit peptide (Hager and Holocher, 1994; Jarvis and López-Juez, 2013). As a crucial enzyme in the xanthophyll cycle, VDE catalyzes the conversion of violaxanthin to zeaxanthin in excess light. It is known that this conversion can protect the photosynthetic apparatus from photodamage and photoinhibition by dissipating excess light energy as heat (Demmig-Adams and Adams, 1996). In addition, it also has been demonstrated that VDE could directly participate in reducing photoinhibition (Gao et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2012). However, photoinhibition is induced not only by high light but also by stressful conditions unfavorable for photosynthetic carbon metabolism, such as heat, chilling, and salt (Murata et al., 2007), suggesting that VDE can respond to abiotic stress, resulting in enhanced tolerance of plants. Recently, VDE was shown to respond to biotic stress (Zhou et al., 2015), and its expression was induced in eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIFiso4G-knockout Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) plants (Chen et al., 2014), which have recessive resistance against potyviruses (Albar et al., 2006; Nicaise et al., 2007).

In this study, we confirmed the specific interaction between ZmVDE and SCMV HC-Pro in both yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) and coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assays and determined an amino acid in ZmVDE and a domain in SCMV HC-Pro that were essential for the interaction. Our results demonstrated that this specific interaction led to attenuation of the RSS activity of the viral protein. Subsequently, transient silencing of the ZmVDE gene significantly increased the accumulation of SCMV. In addition, the influence of SCMV infection on ZmVDE expression levels and ZmVDE subcellular localization was analyzed. In summary, ZmVDE was found to specifically inhibit SCMV accumulation through its interaction with SCMV HC-Pro or combined with other unknown mechanisms.

RESULTS

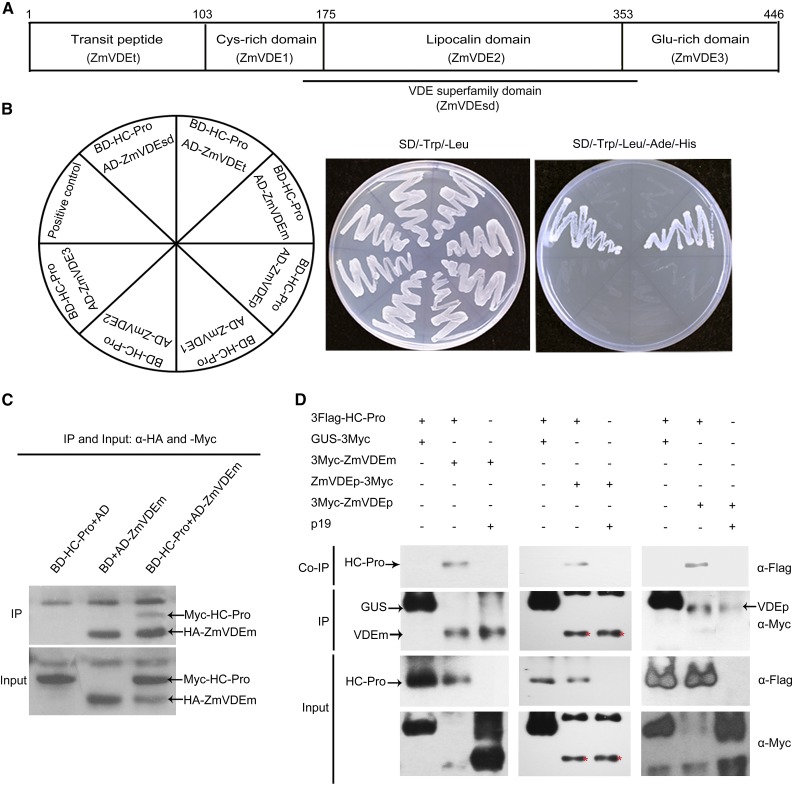

The Chloroplast Protein ZmVDE Interacted with SCMV HC-Pro via Its Mature Protein Region

To identify maize proteins that interacted with SCMV HC-Pro, a Y2H screen of a maize leaf cDNA library (Cheng et al., 2008) was performed using SCMV HC-Pro as a bait. As a result, five identical, independent clones in the screen were obtained, and a BLAST query of the deduced amino acid sequences revealed that these sequences are closely related to maize VDE and that all clones had a conserved VDE superfamily domain (Fig. 1A). To confirm the screen data, the coding sequences of the mature ZmVDE protein (ZmVDEm) lacking the predicated N-terminal transit peptide-coding sequence and the full-length ZmVDE precursor protein (ZmVDEp) were inserted into the vector pGADT7 and cotransformed with pGBKT7-HC-Pro into yeast, respectively. The interaction between ZmVDEm and SCMV HC-Pro in yeast was confirmed (Fig. 1B). However, no interaction was detected in yeast cells cotransformed with ZmVDEp and SCMV HC-Pro (Fig. 1B), which was possibly due to limitations of the yeast system, although ZmVDEp was expressed (Supplemental Fig. S1). In addition, negative controls of yeast cells cotransformed with Activation Domain (AD)-ZmVDEm and empty pGBKT7 vector or Binding Domain (BD)-HC-Pro and empty pGADT7 vector did not form colonies on selective medium (data not shown).

Figure 1.

ZmVDE interacts with SCMV HC-Pro via its mature protein region. A, Schematic description of ZmVDE domains. The black line indicates the ZmVDE superfamily domain. B, Growth of yeast cells cotransformed with BD-HC-Pro and AD-ZmVDEm (the mature ZmVDE protein), AD-ZmVDEp (ZmVDE precursor), AD-ZmVDE1 (Cys-rich domain), AD-ZmVDE2 (lipocalin domain), AD-ZmVDE3 (Glu-rich domain), AD-ZmVDEsd (superfamily domain), or AD-ZmVDEt (transit peptide) on a low-stringency (SD/-Trp/-Leu) or a high-stringency (SD/-Trp/-Leu/-Ade/-His) selective medium. On the left, the schematic representation indicates the positioning of each plasmid combination. C, Co-IP of ZmVDEm and SCMV HC-Pro in vitro. The combinations of BD-HC-Pro and AD or BD and AD-ZmVDEm were used as negative controls. The Co-IP assay was performed using an anti-hemagglutinin (HA) body. IP, Immunoprecipitation. D, Co-IP of ZmVDE and SCMV HC-Pro in planta. 3Flag-HC-Pro was coexpressed with 3Myc-ZmVDEm, ZmVDEp-3Myc, or 3Myc-ZmVDEp in N. benthamiana leaves by agroinfiltration. 3Flag-HC-Pro coexpressed with GUS-3Myc, and p19 coexpressed with 3Myc-ZmVDEm, ZmVDEp-3Myc, or 3Myc-ZmVDEp, were used as negative controls. The Co-IP assay was performed using anti-c-Myc agarose affinity gel. Protein extracts (third and bottom rows) and immunoprecipitates (top and second rows) were immunoblotted with anti-Flag or anti-c-Myc antibodies. Red asterisks indicate the expected ZmVDEm size.

To determine the specific domain of ZmVDE involved in the interaction with SCMV HC-Pro, ZmVDE deletion mutants were generated to test their abilities to interact with SCMV HC-Pro in yeast cells. The results showed that a Cys-rich domain (ZmVDE1), a lipocalin domain (ZmVDE2), a Glu-rich domain (ZmVDE3), a conserved VDE superfamily domain (ZmVDEsd), and a nonconserved N-terminal transit peptide (ZmVDEt; Fig. 1A) all failed to interact with SCMV HC-Pro (Fig. 1B), suggesting that any individual domain of ZmVDE was unlikely to interact with SCMV HC-Pro. Moreover, positive interactions were not detected between ZmVDEm and the other 10 SCMV-encoded proteins (Supplemental Fig. S2). These data indicated that ZmVDE interacted specifically with SCMV HC-Pro via its mature protein region.

To confirm the direct interaction between ZmVDEm and SCMV HC-Pro, ZmVDEm and SCMV HC-Pro translated in vitro were used in a Co-IP assay (Fig. 1C). The HA-ZmVDEm immunoprecipitates were found to be associated with Myc-HC-Pro protein when AD-ZmVDEm was coexpressed with BD-HC-Pro (Fig. 1C, top gel, lane 3), while no Myc-HC-Pro band was detected in the combination of BD-HC-Pro and AD or BD and AD-ZmVDEm (Fig. 1C, top gel, lanes 1 and 2).

In order to investigate the interaction between ZmVDE and SCMV HC-Pro in planta, 3Flag-HC-Pro coexpressed with 3Myc-ZmVDEm, ZmVDEp-3Myc, or 3Myc-ZmVDEp in agroinfiltrated N. benthamiana leaves was used in Co-IP assays (Fig. 1D). 3Flag-HC-Pro coexpressed with GUS-3Myc and p19 coexpressed with 3Myc-ZmVDEm, ZmVDEp-3Myc, or 3Myc-ZmVDEp were used as negative controls. Total protein extracts were prepared, and immunoblotting was performed to assess the expression of input proteins (Fig. 1D, third and bottom rows). The expression of Flag-tagged HC-Pro and Myc-tagged ZmVDEm was detected in all expected-positive samples. However, the molecular mass values of the expressed ZmVDEp-3Myc and 3Myc-ZmVDEp were immunodetected to be approximately 43 and 54 kD, which corresponded to the predicted sizes of ZmVDEm and ZmVDEp, respectively, suggesting that ZmVDEp with a tag at its C terminus could be processed to produce mature ZmVDE but could not be processed with a tag at its N terminus. As expression of all the tagged proteins was confirmed, Co-IP assays were performed by immunoprecipitating Myc-tagged proteins. SCMV HC-Pro was found to be associated with the ZmVDE mature form (3Myc-ZmVDEm and expressed from ZmVDEp-3Myc) and the precursor form (3Myc-ZmVDEp), while the negative controls did not display a positive interaction (Fig. 1D, top and second rows). Taken together, these results provided convincing evidence of the interaction between SCMV HC-Pro and ZmVDE in planta.

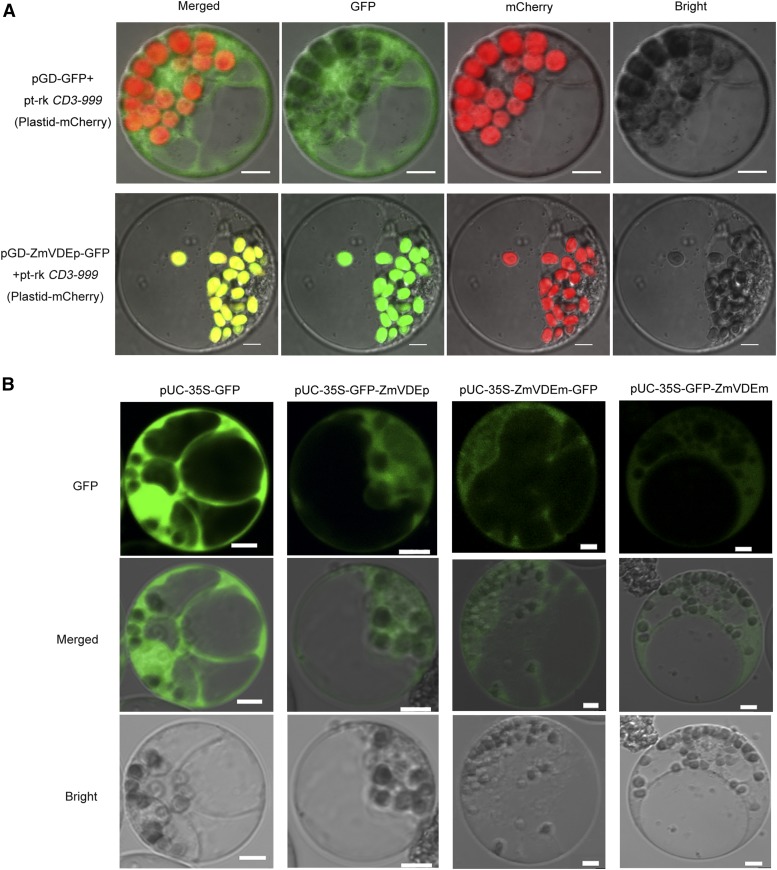

ZmVDE Localized in the Chloroplasts and Cytoplasm in Maize Protoplasts

To determine the subcellular localization of ZmVDE in maize, pGD-ZmVDEp-GFP and pt-rk CD3-999 (Nelson et al., 2007) expressing a plastid marker protein were cotransfected into maize protoplasts, and protoplasts cotransfected with pGD-GFP and pt-rk CD3-999 were used as a control. Compared with the control, the green fluorescence perfectly colocalized with the red fluorescence (plastid localization signal) upon the expression of ZmVDEp-GFP (Fig. 2A), whose N-terminal transit peptide can be removed to produce the mature ZmVDE. Furthermore, the green fluorescence was distributed in the cytoplasm when ZmVDE precursor (GFP-ZmVDEp) was expressed (Fig. 2B). In addition, green fluorescence was distributed in the cytoplasm for both ZmVDEm fusion proteins (Fig. 2B), suggesting that ZmVDE lacking the transit peptide constitutively localized in the cytoplasm, and a tag at its N or C terminus had no visible effect on its subcellular localization. The fluorescence for GFP alone (used as a control) was distributed in both the cytoplasm and nucleus (Fig. 2B). These results suggested that ZmVDE localized in both the chloroplasts (the mature form) and the cytoplasm (mostly the full-length precursor form).

Figure 2.

Subcellular localization of ZmVDE in maize protoplasts. A, Maize protoplasts were cotransfected with plasmids as indicated on the left side of each image. pt-rk CD3-999 expressed a plastid marker protein exhibiting red fluorescence. B, Maize protoplasts were transfected with plasmid as indicated above each column. The transfected protoplasts were visualized at 18 to 24 h post transfection by confocal microscopy. Bars = 5 µm.

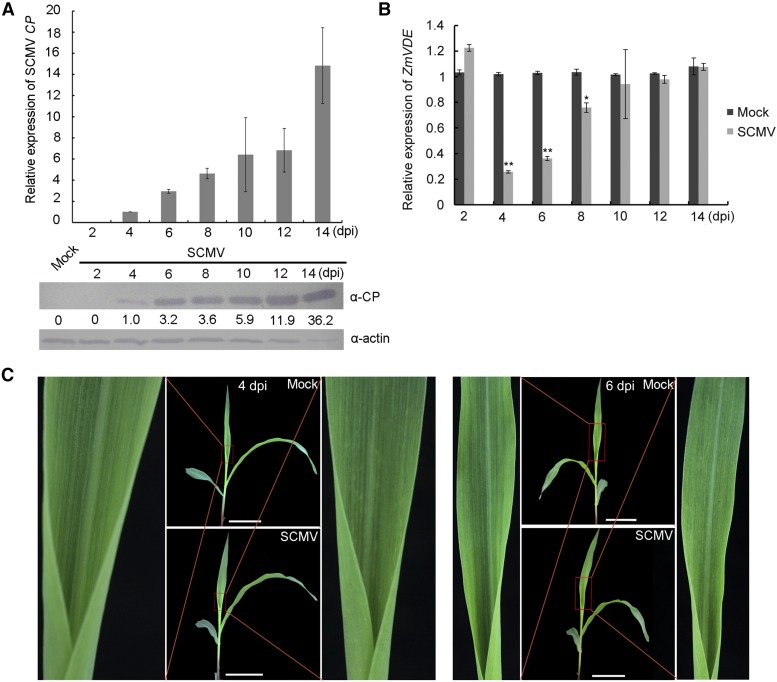

SCMV Infection Altered the Expression Levels of ZmVDE

To determine the effect of SCMV infection on the expression levels of ZmVDE, the first upper leaves of either mock- or SCMV-inoculated maize (inbred line B73) leaves were collected at 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14 d post inoculation (dpi). Then, the presence of SCMV and the expression levels of ZmVDE in the collected tissues were determined by reverse transcription-quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) and western blotting. The results showed that the accumulations of SCMV RNA and CP were detected at six tested time points (Fig. 3A). At 4 dpi, the first systemically infected leaves started to show mild mosaic symptoms (Fig. 3C) and SCMV accumulation was detected (Fig. 3A). At this time point, ZmVDE mRNAs were reduced by 75% in SCMV-infected leaves compared with mock-inoculated leaves (Fig. 3B). At 6 dpi, the first systemically infected leaves showed typical mosaic symptoms (Fig. 3C) and SCMV accumulated to much higher levels (Fig. 3A). At this time point, ZmVDE mRNAs were reduced by 65% in SCMV-infected leaves compared with mock-inoculated leaves (Fig. 3B). At 8 dpi, ZmVDE mRNAs were slightly lower in SCMV-infected leaves than in mock-inoculated leaves, and this difference started to disappear from 10 dpi (Fig. 3B). In addition, the protein levels of ZmVDE also were down-regulated to varying degrees from 4 dpi in SCMV-infected leaves compared with mock-inoculated leaves (data not shown).

Figure 3.

SCMV infection down-regulates the mRNA transcript levels of ZmVDE at an early stage. A, The relative expression levels of SCMV RNAs and CP were determined at 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14 dpi with SCMV by RT-qPCR and western blotting, respectively. Accumulations of maize actin in these samples were used as loading controls. Numbers indicate the relative CP protein levels normalized to the loading control. B, Relative mRNA transcript levels of ZmVDE in the first upper leaves of maize (B73) seedlings inoculated with either 0.01 m phosphate buffer (mock) or SCMV were determined at 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 and 14 dpi by RT-qPCR. The relative quantification of ZmVDE was normalized to the ubiquitin gene used as an internal control. Two independent experiments were conducted with eight biological replicates each. Bars represent mean values ± sd. The single and double asterisks indicate significant differences between treatment means at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, by Student’s t test. C, Symptoms of the first systemically infected maize leaves at 4 and 6 dpi. Bars = 5 cm.

Taken together, these results indicated that SCMV infection significantly down-regulated ZmVDE mRNA levels in the early stage.

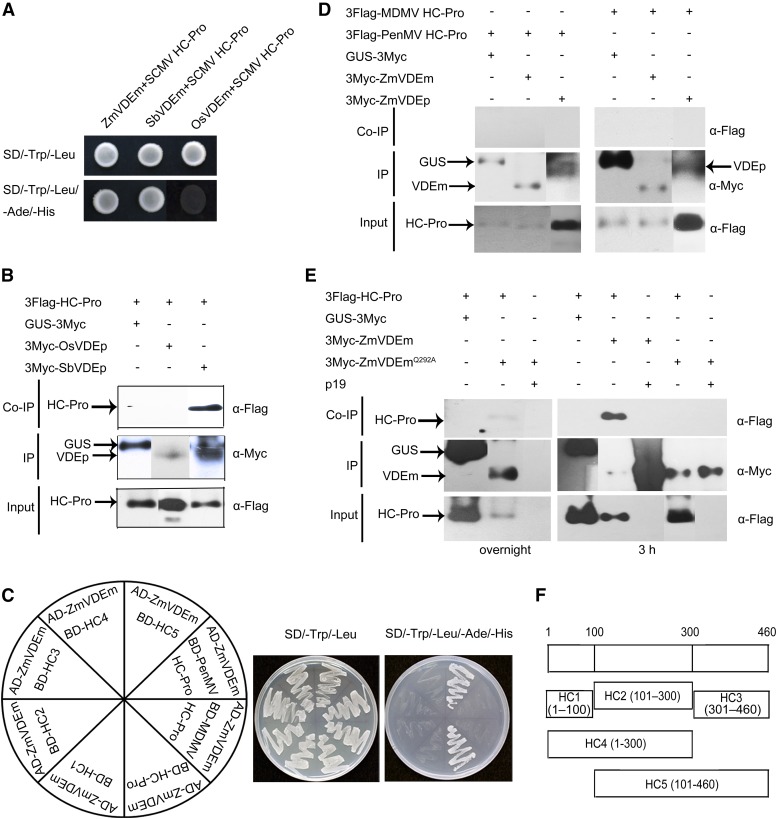

ZmVDE-HC-Pro Interaction Was Specific, and Amino Acid Gln-292 in ZmVDEm and Amino Acids 101 to 460 in HC-Pro Were Responsible for the Interaction

The above results prompted us to investigate the interaction specificity between VDEs and HC-Pros. Alignment and phylogenetic analysis of VDE amino acid sequences in eight plant species showed that ZmVDE was more closely related to the VDE of sorghum (a host of SCMV) than to six other nonhost plant species (Supplemental Fig. S3); therefore, interactions between SCMV HC-Pro and VDEms from sorghum (Sorghum bicolor; SbVDEm) and rice (Oryza sativa ‘Nipponbare’; OsVDEm) were analyzed through Y2H assay. Only a positive interaction between SbVDEm and SCMV HC-Pro was detected, and the interaction between SbVDEp and SCMV HC-Pro was confirmed in Co-IP assay (Fig. 4, A and B). In addition, no interactions were detected between ZmVDE and the HC-Pro from two other maize-infecting potyviruses, Pennisetum mosaic virus (PenMV; Fan et al., 2004) and Maize dwarf mosaic virus (MDMV; Stewart et al., 2012), using Y2H and Co-IP assays (Fig. 4, C and D). These results indicated that only the VDE from host plants of SCMV (maize and sorghum) interacted with SCMV HC-Pro.

Figure 4.

Identification of the interaction specificity between VDEs and HC-Pros from different sources, and the amino acid and domain responsible for the interaction between ZmVDE and SCMV HC-Pro. A, Growth of yeast cells cotransformed with BD-HC-Pro and AD-ZmVDEm, AD-SbVDEm, or AD-OsVDEm on a low-stringency (SD/-Trp/-Leu) or a high-stringency (SD/-Trp/-Leu/-Ade/-His) selective medium. B, Co-IP of SCMV HC-Pro and OsVDEp or SbVDEp in planta. IP, Immunoprecipitation. C, Growth of yeast cells cotransformed with AD-ZmVDEm and BD-HC-Pro, BD-HC1, BD-HC2, BD-HC3, BD-HC4, BD-HC5, BD-MDMV HC-Pro, or BD-PenMV HC-Pro on SD/-Trp/-Leu or SD/-Trp/-Leu/-Ade/-His. D, Co-IP of MDMV HC-Pro, PenMV HC-Pro, and ZmVDEm or ZmVDEp in planta. E, ZmVDEmQ292A has much lower binding affinity to SCMV HC-Pro compared with ZmVDEm. Equal amounts of total protein extracts were used in immunoprecipitation experiments. Overnight indicates that immunoprecipitation was conducted overnight, and 3 h indicates that immunoprecipitation was conducted for 3 h. F, Schematic description of deletion mutants of SCMV HC-Pro. HC-Pro can be divided schematically into five regions: HC1 (residues 1–100), HC2 (residues 101–300), HC3 (residues 301–460), HC4 (residues 1–300), and HC5 (residues 101–460). For B, D, and E, the corresponding proteins were transiently expressed in N. benthamiana leaves by agroinfiltration. The N. benthamiana leaves coexpressing 3Flag-HC-Pro and GUS-3Myc (B and E), 3Flag-MDMV HC-Pro and GUS-3Myc, 3Flag-PenMV HC-Pro and GUS-3Myc (D) or p19 and 3Myc-OsVDEp, 3Myc-SbVDEp (B), 3Myc-ZmVDEm, 3Myc-ZmVDEp (D), 3Myc-ZmVDEm or 3Myc-ZmVDEmQ292A (E) were used as negative controls. Co-IP assays were performed using anti-c-Myc agarose affinity gel. Protein extracts (third rows) and immunoprecipitates (first and second rows) were immunoblotted with appropriate antibodies.

To determine the specific amino acid of ZmVDE responsible for this interaction, six candidate amino acids in α-helices of ZmVDEm, which are identical to those found at the same positions of SbVDEm and different from those found at the same positions of OsVDEm, were substituted with Ala to detect their abilities to interact with SCMV HC-Pro in Y2H assays; as a result, ZmVDEmQ292A did not interact with SCMV HC-Pro (Supplemental Fig. S4), despite being expressed (Supplemental Fig. S1). Then, a Co-IP assay was performed (immunoprecipitating overnight) to confirm this result in planta; as a result, the low abundance of HC-Pro was coimmunoprecipitated with ZmVDEmQ292A (Fig. 4E, left column, top gel). However, when Co-IP was performed (immunoprecipitating for 3 h) using equal amounts of protein extracts, ZmVDEmQ292A showed much weaker binding affinity to HC-Pro than did ZmVDEm (Fig. 4E, right column, top gel). Therefore, the amino acid Gln-292 in ZmVDEm was essential for the interaction with SCMV HC-Pro.

In order to investigate which domain of HC-Pro is necessary for the interaction with ZmVDE, the coding sequences of each functional domain of HC-Pro reported by Plisson et al. (2003; Fig. 4F) were constructed into pGBKT7 and then cotransformed with ZmVDEm into yeast cells. As shown in Figure 4C, only truncated HC5 (residues 101–460) could interact with ZmVDEm in Y2H assays, whereas all other derivatives of HC-Pro lost their interaction activity (Fig. 4C), suggesting that the central and C-terminal regions of HC-Pro play an important role in the interaction between SCMV HC-Pro and ZmVDE. Interestingly, both regions of HC-Pro were reported to be involved in RSS (Plisson et al., 2003), and a functional correlation between them was verified by a strong signature of coevolution (Hasiów-Jaroszewska et al., 2014).

ZmVDE Relocalized to Aggregate Bodies in the Presence of HC-Pro or SCMV

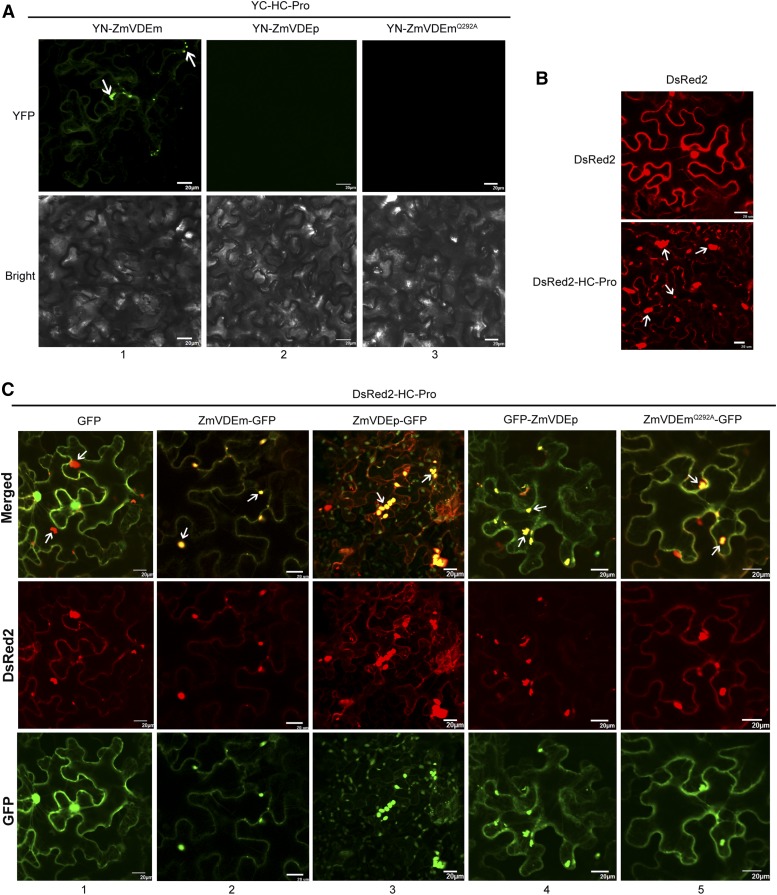

In order to determine the subcellular localization of the ZmVDE and SCMV HC-Pro interaction, a bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assay was performed. ZmVDEm, ZmVDEp, and ZmVDEmQ292A were tagged with the N-terminal half of YFP (YN173) to generate YN-ZmVDEm, YN-ZmVDEp, and YN-ZmVDEmQ292A, respectively. HC-Pro was tagged with the C-terminal half of YFP (YC155) to generate YC-HC-Pro. YC-HC-Pro and YN-ZmVDEm were coexpressed in N. benthamiana leaves, and reconstituted YFP fluorescence was detected in the cytoplasm and aggregate bodies (Fig. 5A, column 1), whereas no YFP signal was detected in the samples expressing YC-HC-Pro and YN-ZmVDEp (Fig. 5A, column 2), possibly due to incorrect protein folding or a low abundance of YN-ZmVDEp and/or SCMV HC-Pro. As expected, coexpression of YC-HC-Pro and YN-ZmVDEmQ292A did not result in detectable YFP fluorescence (Fig. 5A, column 3) due to the weak ability of ZmVDEmQ292A to associate with SCMV HC-Pro. These findings provided evidence that ZmVDE and SCMV HC-Pro could be colocalized to aggregate bodies.

Figure 5.

ZmVDE and ZmVDEmQ292A relocalize to SCMV HC-Pro-containing aggregate bodies. A, BiFC detection of interactions between SCMV HC-Pro and ZmVDEm, ZmVDEp, or the mutant ZmVDEmQ292A in N. benthamiana epidermal cells. B, Confocal micrographs of N. benthamiana leaves agroinfiltrated with pGDR-HC-Pro expressing DsRed2-tagged SCMV HC-Pro (DsRed2-HC-Pro) or pGDR expressing DsRed2. C, Confocal micrographs of N. benthamiana leaves coagroinfiltrated with plasmids expressing DsRed2-HC-Pro and GFP, ZmVDEm-GFP, ZmVDEp-GFP, GFP-ZmVDEp, or the mutant ZmVDEmQ292A-GFP. White arrows point to aggregate bodies. Bars = 20 µm.

Confocal micrographs of the N. benthamiana leaf cells transiently expressing DsRed2-tagged HC-Pro showed that red fluorescence was distributed in the cytoplasm and irregular aggregate bodies were formed in contrast to the control (free DsRed2; Fig. 5B), suggesting that SCMV HC-Pro is a component of the aggregate bodies. Then, the N. benthamiana leaves were coagroinfiltrated to transiently express p19 (to enhance protein expression) and one of the fusion proteins ZmVDEm-GFP, ZmVDEp-GFP, GFP-ZmVDEp, or the mutant ZmVDEmQ292A-GFP. These results showed that green fluorescence was distributed in the cytoplasm when one of the fusion proteins, ZmVDEm-GFP, GFP-ZmVDEp, or ZmVDEmQ292A-GFP, was expressed (Supplemental Fig. S5A, columns 1, 5, and 6). When the fusion protein ZmVDEp-GFP was expressed, green fluorescence was distributed mainly in the chloroplasts and slightly in the cytoplasm (Supplemental Fig. S5A, columns 2 and 3), consistent with the results observed in maize protoplasts (Fig. 2A). In addition, green fluorescence could be observed in the chloroplast stromules upon expression of ZmVDEp-GFP (Supplemental Fig. S5A, column 4).

However, green fluorescence was redistributed to HC-Pro-containing aggregate bodies when one of the fusion proteins ZmVDEm-GFP, ZmVDEp-GFP, GFP-ZmVDEp, or ZmVDEmQ292A-GFP was coexpressed with DsRed2-HC-Pro in N. benthamiana leaves (Fig. 5C, columns 2–5), while their distribution showed no alteration when coexpressed with DsRed2 (Supplemental Fig. S5B). Meanwhile, when the fusion protein ZmVDEp-GFP was coexpressed with DsRed2-HC-Pro, green florescence still could be distributed in the chloroplasts (Supplemental Fig. S6A) and chloroplast stromules (Supplemental Fig. S6B). However, no HC-Pro was detected in maize chloroplasts upon SCMV infection (Supplemental Fig. S7). In addition, a similar localization pattern was observed when GFP-ZmVDEm or GFP-ZmVDEmQ292A (compared with ZmVDEm-GFP or ZmVDEmQ292A-GFP) was coexpressed with p19, DsRed2-HC-Pro, or DsRed2 (control; Supplemental Fig. S8, A–C). These findings prompted us to use ZmVDEm-GFP and ZmVDEmQ292A-GFP in subsequent experiments.

In addition, green fluorescence failed to redistribute to aggregate bodies containing MDMV HC-Pro or PenMV HC-Pro when ZmVDEm-GFP, ZmVDEp-GFP, or GFP-ZmVDEp was coexpressed with MDMV HC-Pro or PenMV HC-Pro, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S9). Although DsRed2-tagged MDMV HC-Pro existed in a large amount in irregular aggregate bodies (Supplemental Fig. S9A), only several small GFP-labeled aggregate bodies were observed (Supplemental Fig. S9B). Interestingly, unlike ZmVDEm-GFP, the localization of OsVDEm-GFP was not altered in the presence of DsRed2-SCMV HC-Pro, DsRed2-MDMV HC-Pro, or DsRed2-PenMV HC-Pro (Supplemental Fig. S10, B–D) and remained solely in the cytoplasm, which is consistent with the result in the presence of p19 (Supplemental Fig. S10A).

Moreover, a significant increase in the percentage of GFP-labeled proteins in HC-Pro-containing aggregate bodies was observed when ZmVDEm-GFP, ZmVDEp-GFP, GFP-ZmVDEp, or ZmVDEmQ292A-GFP (in contrast to the negative controls of GFP or OsVDEm-GFP) was coexpressed with DsRed2-HC-Pro (Supplemental Fig. S11A), and the four fusion proteins had no obvious effect on the quantity of DsRed2-HC-Pro-containing aggregate bodies (Supplemental Fig. S11B). Collectively, the above results suggested that ZmVDE, including the mature form (ZmVDEm-GFP and expressed from ZmVDEp-GFP) and the precursor form (GFP-ZmVDEp), specifically relocalized to HC-Pro-containing aggregate bodies in the presence of SCMV HC-Pro, which is correlated indirectly with the interaction between ZmVDE and SCMV HC-Pro.

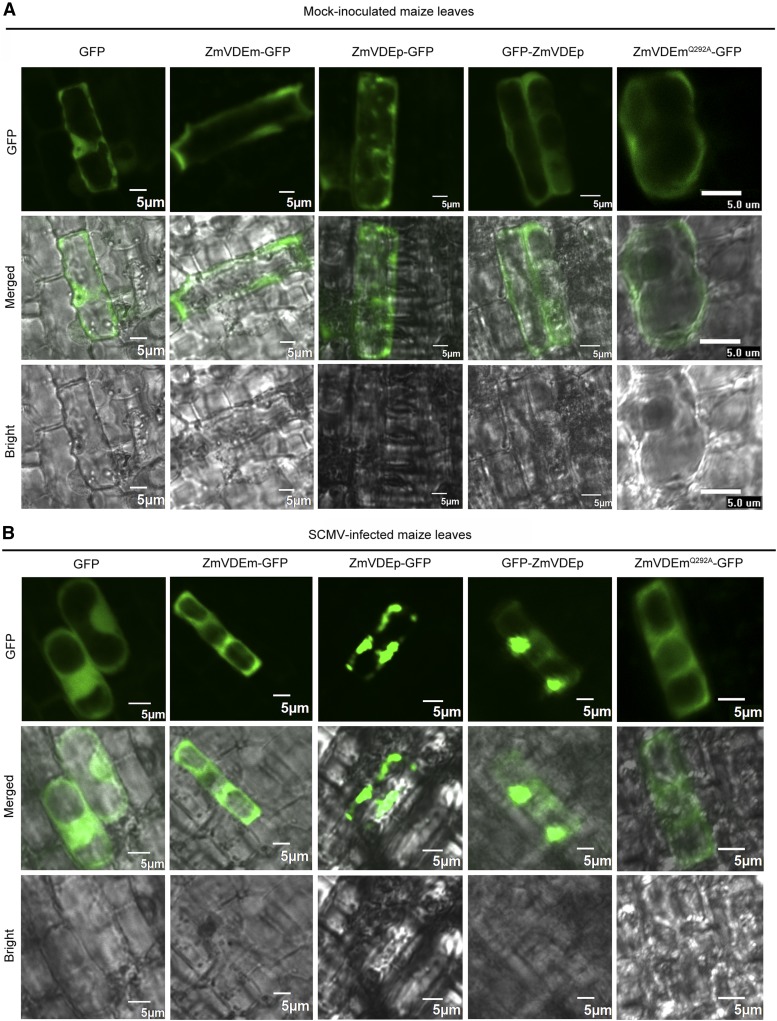

In order to determine whether a similar localization pattern of ZmVDE was exhibited after SCMV infection, gold particles coated with pGD-GFP, pGD-ZmVDEm-GFP, pGD-ZmVDEp-GFP, pGD-GFP-ZmVDEp, or pGD-ZmVDEmQ292A-GFP were bombarded to mock- and SCMV-inoculated maize (B73) leaves. GFP fluorescence was observed at 24 h post bombardment. When ZmVDEm-GFP, GFP-ZmVDEp, or ZmVDEmQ292A-GFP was expressed in maize epidermal cells in mock-inoculated plants, green fluorescence was distributed in the cytoplasm. In addition, when the fusion protein ZmVDEp-GFP was expressed, green fluorescence was distributed to punctate structures (Fig. 6A), presumably due to the difficulty of being imported into chloroplasts. Interestingly, in the presence of SCMV, obvious GFP-labeled aggregate bodies were observed when either ZmVDEp-GFP or GFP-ZmVDEp was expressed, whereas no obvious GFP-labeled aggregate bodies were observed when either ZmVDEm-GFP or ZmVDEmQ292A-GFP was expressed (Fig. 6B). Moreover, the accumulation of SCMV in tissues to be used for microprojectile bombardment was confirmed by western-blot analysis (Supplemental Fig. S12). These results demonstrated that ZmVDE relocalized to aggregate bodies, albeit to varying extents, during SCMV infection.

Figure 6.

ZmVDE and ZmVDEmQ292A relocalize to aggregate bodies in maize cells in the presence of SCMV. Particles carrying each of five plasmids expressing GFP, ZmVDEm-GFP, ZmVDEp-GFP, GFP-ZmVDEp, or ZmVDEmQ292A-GFP were bombarded into mock- or SCMV-inoculated maize (B73) plants. The bombarded leaves were examined by confocal microscopy at 24 h post bombardment. Bars = 5 µm.

ZmVDE Attenuated the RSS Activity of SCMV HC-Pro in a Specific Protein Interaction-Dependent Manner

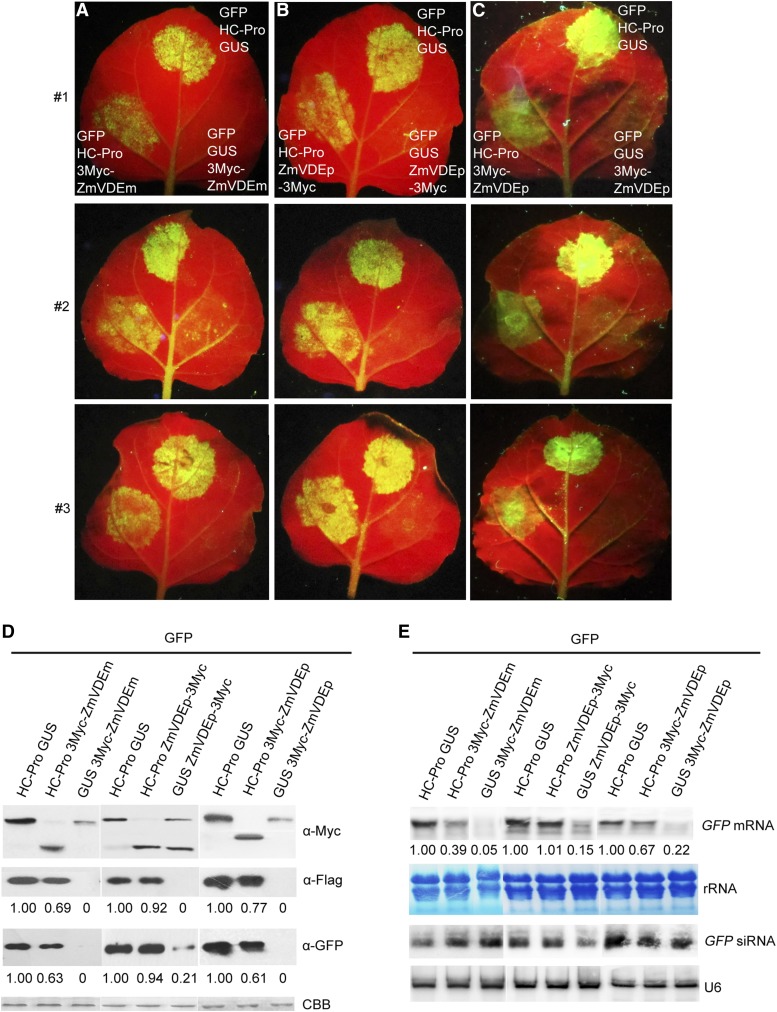

Given that HC-Pro has been well characterized as a VSR, the effect of ZmVDE on its RSS activity was analyzed. At 3 dpi, the N. benthamiana leaves coinfiltrated with a mixture of Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains carrying pGD-GFP, pGD-HC-Pro, and pGD-GUS exhibited high fluorescence in the agroinfiltrated patches (Fig. 7, A–C, top and middle) due to the RSS activity of HC-Pro. However, when pGD-3Myc-ZmVDEm or pGD-3Myc-ZmVDEp was coinfiltrated with pGD-GFP plus pGD-HC-Pro, evidently decreased green fluorescence was observed in the agroinfiltrated patches (Fig. 7, A and C, bottom left), whereas slightly decreased green fluorescence was observed in coinfiltrations that included a mixture of A. tumefaciens strains carrying pGD-ZmVDEp-3Myc, pGD-GFP, and pGD-HC-Pro (Fig. 7B, bottom left). As expected, tissues coinfiltrated with pGD-GFP plus pGD-GUS and pGD-3Myc-ZmVDEm, pGD-ZmVDEp-3Myc, or pGD-3Myc-ZmVDEp exhibited significantly low green fluorescence as a consequence of lacking an RNA silencing suppressor (Fig. 7, A–C, bottom right). Western-blot analysis revealed that GFP protein levels correlated directly with the intensity of green fluorescence; in addition, the decreased GFP protein levels were accompanied by concomitant decreases in HC-Pro protein levels (Fig. 7D). Also, the expression of GUS-3Myc, 3Myc-ZmVDEm, ZmVDEp-3Myc, and 3Myc-ZmVDEp was confirmed (Fig. 7D). Similarly, northern-blot analysis also showed that GFP mRNA levels correlated directly with the intensity of green fluorescence (Fig. 7E), whereas GFP siRNA levels did not (Fig. 7E, lanes 4–9). In line with this, it has been verified that HC-Pro does not down-regulate siRNA accumulation in the sense RNA-induced RNA silencing system (Zhang et al., 2008). In addition, the tags fused to HC-Pro had no obvious effect on its RSS activity (Supplemental Fig. S13). Taken together, these results suggested that ZmVDE could attenuate the RSS activity of SCMV HC-Pro.

Figure 7.

Attenuation of the local RSS activity of SCMV HC-Pro by different forms of ZmVDE. A to C, N. benthamiana leaves were infiltrated with a mixture of three A. tumefaciens cultures carrying different constructs, as indicated in the top row (top middle, bottom left, and bottom right of each leaf), and photographed at 3 d post infiltration. The images in rows 1, 2, and 3 are representatives of at least 50 individual leaf samples. HC-Pro and GUS indicate 3Flag-HC-Pro and GUS-3Myc, respectively. D, Western-blot analysis of protein extracts from N. benthamiana leaves infiltrated with mixtures of A. tumefaciens carrying different constructs as indicated at top. The expression of GUS, 3Myc-ZmVDEm, ZmVDEp-3Myc, and 3Myc-ZmVDEp was confirmed with monoclonal c-Myc antibody. The expression of HC-Pro and GFP was confirmed with monoclonal Flag and GFP antibodies, respectively. Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) staining of the large subunit of Rubisco was used as a loading control. Numbers indicate the relative HC-Pro and GFP protein levels normalized to Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining. E, Northern-blot analysis of the accumulation of GFP mRNA and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) in the above-mentioned leaf samples (D). Methylene Blue staining and U6 hybridization served as loading controls for mRNA and siRNAs, respectively. Numbers indicate the relative GFP mRNA levels normalized to rRNA intensity.

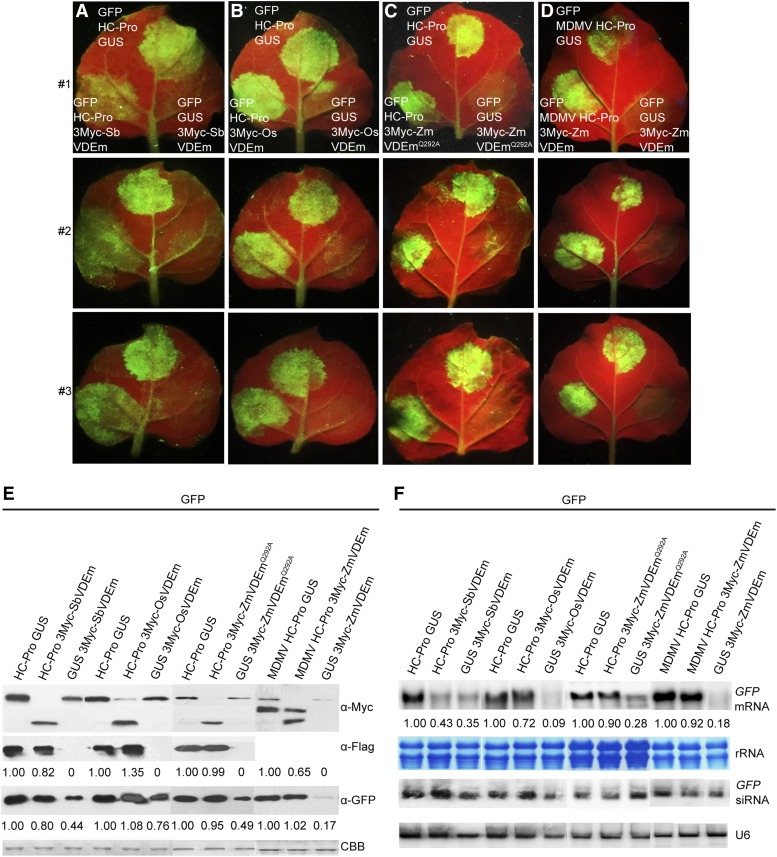

To determine whether this capacity of VDE was required for interaction with SCMV HC-Pro, pGD-3Myc-SbVDEm, pGD-3Myc-OsVDEm, or pGD-3Myc-ZmVDEmQ292A was coinfiltrated with pGD-GFP plus pGD-HC-Pro to observe the intensity of green fluorescence compared with that exhibited in patches infiltrated with a mixture of A. tumefaciens strains carrying pGD-GFP, pGD-HC-Pro, and pGD-GUS. Evidently decreased green fluorescence was observed in patches in which pGD-3Myc-SbVDEm was coinfiltrated (Fig. 8A, bottom left), and consistent with the fluorescence intensity, reduced GFP protein (Fig. 8E) and mRNA levels (Fig. 8F) were detected. However, green fluorescence intensity showed no obvious differences in coinfiltrations with pGD-3Myc-OsVDEm or pGD-3Myc-ZmVDEmQ292A (Fig. 8, B and C, bottom left), and consistent with the fluorescence intensity, no obvious change, or only slight increases, in GFP protein (Fig. 8E) and mRNA levels (Fig. 8F) were detected. In addition, patches infiltrated with pGD-GFP plus pGD-GUS and pGD-3Myc-SbVDEm, pGD-3Myc-OsVDEm, or pGD-3Myc-ZmVDEmQ292A also exhibited significantly low green fluorescence (Fig. 8, A–C, bottom right) and contained low levels of GFP protein (Fig. 8E) and mRNA (Fig. 8F). These results indicated that only SCMV HC-Pro-interacting VDE could attenuate the RSS activity of SCMV HC-Pro.

Figure 8.

Attenuation of the local RSS activity of SCMV HC-Pro by its specific interactor VDE. A to D, N. benthamiana leaves were infiltrated with a mixture of three A. tumefaciens cultures carrying different constructs, as indicated in the top row (top middle, bottom left, and bottom right of each leaf), and photographed at 3 d post infiltration. The images in rows 1, 2, and 3 are representatives of at least 50 individual leaf samples. HC-Pro, MDMV HC-Pro, and GUS indicate 3Flag-HC-Pro, MDMV HC-Pro-3Myc, and GUS-3Myc fusion proteins, respectively. E, Western-blot analysis of protein extracts from N. benthamiana leaves infiltrated with mixtures of A. tumefaciens carrying different constructs as indicated at top. The expression of GUS, 3Myc-SbVDEm, 3Myc-OsVDEm, 3Myc-ZmVDEmQ292A, and MDMV HC-Pro was confirmed using monoclonal c-Myc antibody. The expression of HC-Pro and GFP was confirmed using monoclonal Flag and GFP antibodies, respectively. Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) staining of the large subunit of Rubisco was used as a loading control. Numbers indicate the relative HC-Pro, MDMV HC-Pro, and GFP protein levels normalized to Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining. F, Northern-blot analysis of the accumulation of GFP mRNA and siRNAs in the above-mentioned leaf samples (E). Methylene Blue staining and U6 hybridization served as loading controls for mRNA and siRNAs, respectively. Numbers indicate the relative GFP mRNA levels normalized to rRNA intensity.

Besides, to confirm whether ZmVDE affects the RSS activity of noninteracting HC-Pro, pGD-MDMV HC-Pro was coinfiltrated with pGD-GFP plus pGD-3Myc-ZmVDEm to observe the intensity of green fluorescence compared with that exhibited in patches infiltrated with a mixture of A. tumefaciens strains carrying pGD-GFP, pGD-MDMV HC-Pro, and pGD-GUS. Interestingly, the green fluorescence showed no obvious difference (Fig. 8D), consistent with no evident change in GFP protein (Fig. 8E) and mRNA levels (Fig. 8F). However, the decreased MDMV HC-Pro protein level also was detected, suggesting that the decreased green fluorescence is possibly correlated indirectly with the decreased HC-Pro levels. Eventually, another distinct silencing suppressor, p19 from Tomato bushy stunt virus, was coexpressed with GFP, or GFP and GUS, ZmVDEm, ZmVDEp, SbVDEm, or OsVDEm to observe the difference of green fluorescence intensity among patches infiltrated with different combinations of constructs. Slightly increased green fluorescence and elevated levels of GFP protein and mRNA were observed in patches infiltrated with p19 plus GFP and ZmVDEm, ZmVDEp, SbVDEm, or OsVDEm compared with those exhibited in patches infiltrated with p19, GFP, and GUS (Supplemental Fig. S14). Collectively, these findings suggested that HC-Pro interaction with ZmVDE is necessary for ZmVDE to attenuate its RSS activity.

Knockdown of ZmVDE Expression Facilitated SCMV Infection in Maize Plants

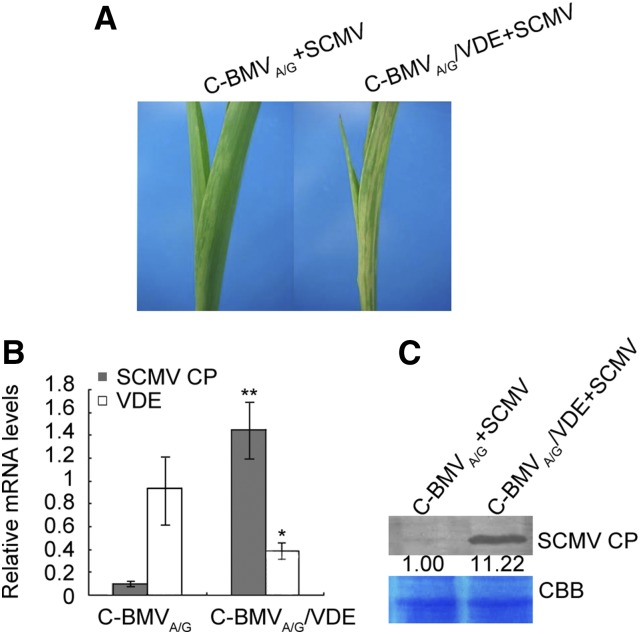

To investigate the potential role of ZmVDE during SCMV infection, the Brome mosaic virus (BMV)-based vector pC-BMVA/G (Ding et al., 2006) was used to transiently silence ZmVDE. A 180-bp fragment of ZmVDE amplified from the 3ʹ untranslated region of the gene was inserted into pC-BMVA/G to generate pC-BMVA/G/ZmVDE. The transcripts of pC-BMVA/G/ZmVDE and pC-BMVA/G were rub inoculated to N. benthamiana leaves. The N. benthamiana leaves were harvested at 5 dpi and analyzed by reverse transcription-PCR to confirm the infection of BMV and the presence of the ZmVDE gene insert (data not shown). Then, the crude extracts of the harvested N. benthamiana leaves were rub inoculated onto leaves of maize (inbred line Va35) seedlings. The second upper leaves systemically infected by BMV were challenge inoculated with SCMV at 10 dpi. The initial symptoms appeared on the first systemically coinfected leaves at 5 dpi, and ZmVDE-silenced plants (C-BMVA/G/ZmVDE) showed more severe symptoms (exhibiting more expanded chlorosis areas) compared with the control plants (C-BMVA/G; Fig. 9A). The first systemically infected leaves (by SCMV) of each assayed plant were harvested at 6 dpi to determine ZmVDE transcript silencing efficiency and SCMV RNA and CP protein accumulation. The results showed that, at 6 dpi (with SCMV), an approximately 50% decrease in ZmVDE mRNA levels was associated with a more than 10-fold increase in SCMV RNA accumulation (Fig. 9B) and a significant increase in SCMV CP accumulation (Fig. 9C) compared with the control plants. Taken together, these data indicated that silencing of the ZmVDE gene facilitated the accumulation of SCMV.

Figure 9.

Knockdown of ZmVDE in maize plants facilitates the accumulation of SCMV. A, Phenotypes of SCMV challenge inoculation on mock-treated (C-BMVA/G) and ZmVDE-silenced (C-BMVA/G/VDE) maize (Va35) plants. Whole plants were photographed at 6 d post challenge inoculation with SCMV. B, ZmVDE silencing efficiency (white bars) and SCMV RNA accumulation (gray bars) in first systemic leaves SCMV challenge inoculated at 6 dpi were determined by RT-qPCR. The relative quantifications of ZmVDE and SCMV RNA were normalized to the ubiquitin gene used as an internal control. Three independent experiments were conducted with five biological replicates each. All data are mean values ± sd. The single and double asterisks indicate significant differences between treatment means at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively, by Student’s t test. C, Accumulation levels of SCMV CP in first systemic leaves SCMV challenge inoculated at 6 dpi were determined by western blotting. Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) staining of the large subunit of Rubisco was used as a loading control. Numbers indicate the relative SCMV CP protein levels normalized to Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining.

DISCUSSION

The Interaction between ZmVDE and SCMV HC-Pro in the Cytoplasm

VDE (encoded by a nuclear gene) has been characterized as a thylakoid lumen-localized enzyme upon cleavage of its transit peptide (Hager and Holocher, 1994). Our results also suggested that ZmVDE in its native state (ZmVDEp with tags at its C terminus) was imported into the chloroplasts of maize (Fig. 2B) and N. benthamiana (Supplemental Fig. S5A, column 3).

However, the divergent distribution of HC-Pros has been found in different potyviruses. Previous studies indicated that potyviral HC-Pros were distributed to the cytoplasm (Riedel et al., 1998; Mlotshwa et al., 2002; Zheng et al., 2011; Sahana et al., 2014), nucleus (Riedel et al., 1998; Sahana et al., 2014), cytoplasm filaments, cell membrane, or nuclear envelope (Zheng et al., 2011). In addition, Turnip mosaic virus HC-Pro and Potato virus Y (PVY) HC-Pro could form aggregates in the cytoplasm (Zheng et al., 2011; del Toro et al., 2014), and an amino acid change of Papaya ringspot virus HC-Pro also led to the formation of the aggregates (Sahana et al., 2014). Interestingly, PVY HC-Pro also could be present in the chloroplasts of PVY-infected plants (Gunasinghe and Berger, 1991). This discrepancy of HC-Pro distribution may be due to different characteristics of specific viruses. In this study, HC-Pro from each of three maize-infecting potyviruses, SCMV, MDMV, and PenMV, was shown to localize in the cytoplasm and induce aggregate bodies when it was expressed transiently in N. benthamiana leaves (Fig. 5B; Supplemental Fig. S9, A and C).

In this research, we showed that ZmVDEp with a tag at its C terminus (ZmVDEp-3Myc) could be processed to produce mature ZmVDE (ZmVDEm), which interacted with SCMV HC-Pro (Fig. 1D) and localized in the chloroplasts (Fig. 2A; Supplemental Fig. S5A, columns 2 and 3). These results raise the question of whether SCMV HC-Pro exists in maize chloroplasts upon SCMV infection. However, unlike PVY HC-Pro, SCMV HC-Pro was not detected in the chloroplasts of SCMV-infected maize plants, possibly due to the low abundance of HC-Pro, insufficient sensitivity of HC-Pro antibody, and/or unadvisable time points for sampling (Supplemental Fig. S7). We speculate that direct interaction could exist in the cytoplasm, since ZmVDE and SCMV HC-Pro colocalized there (Fig. 5), and their interaction should be necessary in attenuating the RSS activity of SCMV HC-Pro that functions in the cytoplasm (Figs. 7 and 8).

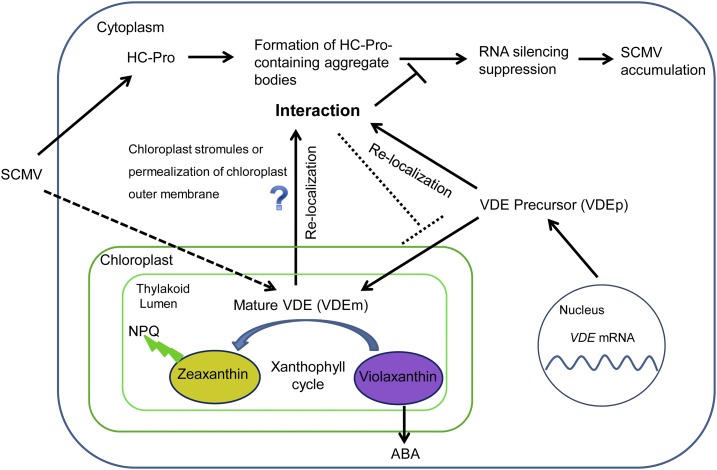

Two forms of VDE existing in plants have been reported: one is the precursor translated in the cytoplasm (Lee et al., 2013) and the other is the mature VDE imported into chloroplasts. An intriguing question is how ZmVDE interacts with SCMV HC-Pro in the cytoplasm (Fig. 10). The interaction between the ZmVDE precursor protein and SCMV HC-Pro in the cytoplasm is intelligible to us. Now that the interaction between the mature ZmVDE (expressed from ZmVDEp-3Myc) and SCMV HC-Pro (Fig. 1D) exists in the cytoplasm, it is likely that the chloroplast-localized ZmVDEm could be transported back into the cytoplasm. Interestingly, several chloroplast proteins involved in cytoplasm and/or nuclear localization have been reported as retrograde signals to modulate nuclear gene expression (Chen et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2011; Isemer et al., 2012). PTM, a membrane-bound transcription factor that localizes to the chloroplast outer envelope by four transmembrane domains at its C terminus, has been found to be activated by proteolytic cleavage of the transmembrane domains and to transmit multiple retrograde chloroplast signals to the nucleus (Sun et al., 2011). In addition, Whirly1 was shown to be dually located in both the chloroplasts and nucleus of the same cell with the same molecular size and to affect the expression of target genes such as PR1 in the nucleus (Isemer et al., 2012). Similarly, it was reported that GFP fusion proteins could be transported from chloroplasts to the cytoplasm upon biotic and abiotic stresses (Kwon et al., 2013). However, the molecular mechanism underlying this phenomenon remains unknown. In this study, we found the green fluorescence signal likely to be distributed in the stromules upon the expression of ZmVDEp-GFP either in the absence or presence of SCMV HC-Pro (Supplemental Figs. S5A, column 4, and S6B). Chloroplast stromules, which are thin projections of stroma-filled tubules emerging from the surface of chloroplasts, have been reported to be associated with abiotic and biotic stresses (Gray et al., 2012; Krenz et al., 2012; Caplan et al., 2015). Although the biological significance of stromules remains unclear, accumulating evidence indicated that the stromules function in trafficking proteins (Krenz et al., 2012; Hanson and Sattarzadeh, 2013; Caplan et al., 2015). Stromules have been found to be induced by effector-triggered immunity, and chloroplast-localized N receptor-interacting protein1 (NRIP1) was transported from chloroplasts into the nucleus during this process through stromules (Caplan et al., 2015). Moreover, in Abutilon mosaic virus-infected leaves, a plastid-targeted heat shock cognate 70-kD protein (chaperone) was found to interact with Abutilon mosaic virus movement protein in the stromules (Krenz et al., 2010), which may facilitate viral transport from chloroplasts into a neighboring cell or the nucleus (Krenz et al., 2012). Therefore, the stromule conduits may be a pathway by which ZmVDEm is transported from chloroplasts back into the cytoplasm upon SCMV infection. Another possibility is that permealization of the chloroplast outer membrane could change upon SCMV infection (Bobik and Burch-Smith, 2015).

Figure 10.

Proposed model for the role of ZmVDE against viral infection. We speculate that ZmVDEp and ZmVDEm relocalize to HC-Pro-containing aggregate bodies and that their interaction with SCMV HC-Pro inhibits the RSS activity of the viral protein and, subsequently, contributes to the decrease in SCMV accumulation. ZmVDE transports back into the cytoplasm via an unknown mechanism (question mark). The dashed arrow indicates that SCMV infection may modulate the activity of ZmVDE, which is involved in the xanthophyll cycle. The dotted line indicates that HC-Pro may inhibit ZmVDE to be imported into chloroplasts. ABA, Abscisic acid.

ZmVDE Relocalized to SCMV HC-Pro-Containing Aggregate Bodies and Attenuated the RSS Activity of HC-Pro via Their Interaction

In plant-virus interactions, VSRs may be regarded as viral effectors that facilitate viral infection in plants. However, some host factors have been demonstrated to interfere with the activity of VSR. For instance, ALY proteins interacted and sequestered p19 in the nucleus and attenuated the RSS activity of p19, but direct evidence of the biological role of ALY in p19 function was not obtained (Canto et al., 2006). Additionally, tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) rgs-CaM has been shown to bind to dsRNA-binding domains of VSR proteins and degrade them through autophagy-like protein degradation pathways, leading to attenuated RSS activity of VSRs and enhanced host antiviral interference against viral infection (Nakahara et al., 2012). Interestingly, our results also demonstrated that ZmVDE could attenuate the RSS activity of SCMV HC-Pro (Fig. 7), providing evidence that ZmVDE can counteract SCMV infection. The fusion protein ZmVDEp-3Myc only slightly attenuated the RSS activity of HC-Pro (Fig. 7B), presumably because ZmVDEp-3Myc was expressed heterologously in N. benthamiana leaves, lacking the regulation of protein processing and chloroplast stromules. In addition, the effect of ZmVDE on HC-Pro silencing suppression activity is specific, and ZmVDE failed to affect the RSS activity of HC-Pro of the closely related MDMV (Fig. 8D), indicating the complexity and specificity of plant-virus interactions. Similarly, recent studies showed that Nbrgs-CaM was up-regulated by βC1 (a VSR) of the geminivirus Tomato yellow leaf curl China virus to repress RDR6 expression, facilitating the geminivirus infection (Li et al., 2014), in contrast to the suggestion that rgs-CaM provides secondary defense by the binding and degradation of VSRs. The opposite effect of rgs-CaM on VSRs is possibly due to its conformational change after Ca2+ binding (Makiyama et al., 2016), suggesting the specific role of rgs-CaM in viral infection. In addition, we found that substitution of the amino acid Gln-292 of ZmVDEm with Ala significantly reduced the affinity of ZmVDE with SCMV HC-Pro (Fig. 4E), and the amino acid Gln-292 of ZmVDE was required to attenuate the RSS activity of SCMV HC-Pro (Fig. 8C), suggesting that plants have evolved various strategies to counteract pathogen attack, including single amino acid substitution.

The colocalization assay showed that 3Myc-ZmVDEm, ZmVDEp-3Myc, and 3Myc-ZmVDEp all colocalized with SCMV HC-Pro-containing aggregate bodies; however, 3Myc-ZmVDEQ292A also was found to colocalize there (Fig. 5C), possibly implying that relocalization of ZmVDE to SCMV HC-Pro was not directly dependent on the interaction with SCMV HC-Pro. In addition, this capacity is specific between ZmVDE and SCMV HC-Pro, because only ZmVDE can relocalize to SCMV HC-Pro-containing aggregate bodies (Fig. 5C; Supplemental Figs. S9, B and D, and S10). The result that ZmVDE relocalized to aggregate bodies also was confirmed in the presence of SCMV (Fig. 6). No obvious aggregate bodies were observed when ZmVDEm-GFP or ZmVDEmQ292A-GFP was expressed, presumably due to the much lower abundance of SCMV in bombarded tissues (Supplemental Fig. S12). In addition, it was demonstrated that Potato virus A HC-Pro induced the formation of RNA granules and localized abundantly there, which played an important role in virus infection (Hafrén et al., 2015). Point mutations that compromised the RSS activity of Potato virus A HC-Pro concomitantly abolished its ability to generate the RNA granules (Hafrén et al., 2015), and conversely, an amino acid substitution in Papaya ringspot virus HC-Pro that increased the formation of aggregate simultaneously increased the capacity of HC-Pro to suppress RNA silencing (Sahana et al., 2014). Han et al. (2016) found that HC-Pro exhibited strong VSR activity and formed large subcellular aggregates by investigating three natural Turnip mosaic virus isolates. These results indicate that the aggregate body localization may contribute to HC-Pro functions. We found that ZmVDE relocalized to SCMV HC-Pro-containing aggregate bodies (Fig. 5) and attenuated the RSS activity of HC-Pro via their interaction (Figs. 7 and 8). However, whether ZmVDE affects other functions of SCMV HC-Pro or whether HC-Pro intercepts ZmVDE to be imported into chloroplasts or directly masks its transit peptide remains to be investigated.

Actually, the abundance of HC-Pro was reduced when it was coexpressed with 3Myc-ZmVDEm, ZmVDEp-3Myc, or 3Myc-ZmVDEp, compared with coexpression with GUS-3Myc (Fig. 1D, third row). Consistent with these results, decreased HC-Pro protein levels also were detected in assays to test the effect of ZmVDE on the RSS activity of SCMV HC-Pro (Fig. 7), suggesting the possibility that ZmVDE attenuates the RSS activity of SCMV HC-Pro via HC-Pro degradation. However, our results demonstrated that ZmVDE did not degrade HC-Pro via the ubiquitination or autophagy pathway (Supplemental Fig. S15). Although we found that the ZmVDE precursor could be degraded through the ubiquitination pathway, its expression also was regulated by the VSR activity of HC-Pro (Supplemental Fig. S15B). In addition, the accumulation level of MDMV HC-Pro also decreased when it was coexpressed with 3Myc-ZmVDEm compared with coexpression with GUS-3Myc (Fig. 8E), but the decreased MDMV HC-Pro had no significant effect on GFP protein expression. Thus, the reduced abundance of SCMV HC-Pro may not be the only reason for the attenuation of its RSS activity by ZmVDE. It is possible that ZmVDE interfered with one or more steps in the RSS pathway of HC-Pro, and the underlying molecular mechanism remains to be investigated.

ZmVDE Plays a Positive Role against SCMV Infection

Most antiviral responses are investigated using dicotyledonous plants, but recently, AGO18 and miRNA528 were reported to be involved in antiviral responses in rice (Wu et al., 2015, 2017). In addition, two quantitative resistance genes against SCMV in maize have been identified (Leng et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017). However, the roles of most host factors during viral infection in monocot plants are poorly understood.

As obligate intracellular organisms, plant viruses must interact with various host factors to complete their life cycle, including virus accumulation and movement. However, there are host factors that influence virus accumulation but are not essential for virus infection and accumulation (Culver and Padmanabhan, 2007). Identifying these host factors and determining the mechanisms underlying these interactions are important for obtaining virus-resistant plant lines.

In this study, the chloroplast protein ZmVDE was found to interact specifically with SCMV HC-Pro (Figs. 1 and 4). It is interesting that SCMV infection down-regulated the expression levels of ZmVDE at the early stage. However, the accumulation of SCMV was enhanced significantly in ZmVDE-silenced maize plants (Fig. 9B). As expected, silencing of the ZmVDE gene did not lead to an unusual visual phenotype, which is consistent with the results of silencing VDE in other plants (Chang et al., 2000). These results indicate that ZmVDE has a function in the defense against SCMV infection, and SCMV possibly has evolved to down-regulate the expression levels of ZmVDE to enhance its own accumulation.

It may seem surprising that ZmVDE expression could be influenced by SCMV accumulation but its expression also could inhibit virus accumulation. However, infections with SCMV or some other viruses are known to alter the transcript levels of nuclear genes encoding chloroplast-localized proteins (Yang et al., 2007; Cheng et al., 2008; Mochizuki et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2017). Meanwhile, the modified transcript levels of particular host chloroplast proteins are reported to alter the accumulation of viruses. Silencing of the chloroplast phosphoglycerate kinase gene (cPGK) or mislocalization of cPGK protein reduced the potexvirus Bamboo mosaic virus accumulation (Lin et al., 2007; Cheng et al., 2013). NRIP1 is responsible for pathogen recognition through its ability to interact with both the plant N immune receptor and the 50-kD helicase (p50) domain of Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), and silencing of NRIP1 facilitated TMV infection (Caplan et al., 2008). In addition, it is interesting that several nuclear genes encoding chloroplast-localized proteins are down-regulated during viral infection, and they also play positive roles in defense against viral infection. In N. benthamiana, Plum pox virus (PPV) infection led to a decrease in psaK mRNA levels. The product of the gene psaK (the PSI-K protein) interacted with the cylindrical inclusion protein of PPV, and silencing of psaK enhanced PPV accumulation (Jiménez et al., 2006). PsbO, a component of the oxygen-evolving complex of PSII, interacted with the helicase domain of the TMV replicase, and silencing of psbO significantly increased TMV accumulation. Also, TMV infection suppressed psbO expression (Abbink et al., 2002). Recently, ATP-synthase γ-subunit and Rubisco activase were reported to be isolated from the TMV replication complex. TMV infection down-regulated their mRNA levels, and silencing of them enhanced viral accumulation (Bhat et al., 2013). Therefore, ZmVDE likely plays a similar role in defense against viral infection.

In this study, we found that ZmVDE interacted with SCMV HC-Pro (Fig. 1) and attenuated the RSS activity of SCMV HC-Pro (Fig. 7); thus, when ZmVDE was silenced, the RSS activity of SCMV HC-Pro would be increased, subsequently contributing to SCMV accumulation. Thus, the above data give us an insight into the role of ZmVDE in the defense against SCMV infection. ZmVDE interacts with SCMV HC-Pro and leads to attenuation of the RSS activity of the latter, contributing to the decrease in SCMV accumulation. This may explain why ZmVDE relocalized to aggregate bodies in the presence of SCMV HC-Pro (Fig. 5) or during SCMV infection (Fig. 6).

In addition, ZmVDE, a component in the xanthophyll cycle, is responsible for catalyzing the conversion of violaxanthin into zeaxanthin, which is involved in thermal energy dissipation assessed as nonphotochemical quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence (Müller et al., 2001). Besides, violaxanthin is an abscisic acid precursor responsible for the de novo synthesis of abscisic acid (Milborrow, 2001). Recently, several reports have demonstrated that the xanthophyll cycle is involved in pathogen attack via the change of physiological functions of VDE (Wilhelmová et al., 2005; Pérez-Bueno et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2015). Therefore, in ZmVDE-silenced maize plants, the reduced activity of ZmVDE also may contribute to the accumulation of SCMV.

Collectively, our data suggest that ZmVDE plays a positive role against SCMV infection, which is summarized in the working model (Fig. 10).

Taken together, these findings suggest that ZmVDE, a chloroplast protein that participates in the xanthophyll cycle, is involved in a specific interaction with SCMV HC-Pro and the attenuation of the RSS activity of the latter.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid Construction

VDE full-length coding sequences amplified from maize (Zea mays), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), and rice (Oryza sativa) are located on chromosome 2, chromosome 6, and chromosome 4, respectively. For the Y2H assay, pGADT7 and pGBKT7 were used to construct N-terminal GAL4 AD or GAL4 DNA BD fusion constructs. For the subcellular localization assay in maize protoplasts, pUC-35S-GFP and pGD (Goodin et al., 2002) were used for the generation of the expression vectors. For transient expression in Nicotiana benthamiana and maize leaves, constructs were based on pGD and pGDR vectors (Goodin et al., 2002). For the BiFC assay, pSPYCE(MR) and pSPYNE(R)173 were used to construct N-terminal YN and YC fusion constructs (Waadt et al., 2008). For the BMV assay, pC-BMVA/G was used to produce pC-BMVA/G/VDE (Ding et al., 2006).

The constructs and primer sets used in this study are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

Plant Growth, Virus Source, and Virus Inoculation

Maize inbred line B73 plants were prepared in growth chambers (28°C day and 22°C night, 16-h-light/8-h-dark cycle) for virus inoculation and expression analysis. SCMV-BJ was from a previously published source (Fan et al., 2003). Crude extracts from SCMV-infected maize leaf tissues were prepared as described previously (Zhu et al., 2014). Vascular puncture inoculation of maize kernels with SCMV was conducted as described previously (Wang et al., 2016).

Y2H Assay

The maize cDNA library screen and the identification of positive interactions were performed as described previously (Cheng et al., 2008). Yeast protein extracts were prepared using the SDS protein extraction method according to the manufacturer’s protocols (Clontech).

Co-IP in Vitro and in Vivo

For in vitro Co-IP, plasmids of pGADT7-ZmVDEm, pGADT7-SbVDEm, pGBKT7-HC-Pro, pGADT7, and pGBKT7 were used for in vitro protein expression by the TnT Quick Coupled Transcription/Translation System (Promega) in the presence of biotinylated tRNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each corresponding reaction mixture (final volume, 50 µL) was incubated at 30°C for 30 min, and 10S buffer (50 mm HEPES at pH 7.2, 10 mm NaH2PO4 at pH 7, 250 mm NaCl, 0.2% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 0.005% SDS) containing 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol, 5 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and protease inhibitor cocktail for yeast cells (Sigma) was added to a final volume of 150 µL. Then, each mixture was incubated with 2 µg of anti-HA antibody for 1 h at 4°C, and 20 µL of Protein G Plus-Agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was added subsequently. After incubation for 1 h at 4°C, the agarose was pelleted and washed four times with 10S buffer.

For in vivo Co-IP, corresponding plasmids were expressed heterologously in 4-week-old N. benthamiana. The N. benthamiana leaves were collected 3 d post agroinfiltration, ground in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C before use. For the assay, total proteins were extracted from approximately 1 g of ground powder in extraction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 10% glycerol) containing 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma) for plant cells. The resulting leaf extracts were centrifuged and subsequently filtered through 0.45-μm filters. After determination of the protein concentration using the Bradford protein assay, equal amounts of protein (approximately 1.2 mL) were immunoprecipitated with 40 μL of anti-c-Myc agarose affinity gel (Sigma) at 4°C for 3 h or overnight on a rotation wheel. The immunoprecipitates were washed four times with ice-cold extraction buffer.

Finally, immunoprecipitation samples were solubilized in loading buffer and heated at 100°C for 5 min. After centrifugation, the proteins were analyzed by western blotting with appropriate antibodies.

RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from maize and N. benthamiana leaves using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) as instructed by the manufacturer and treated with RNase-free DNase I (Takara Bio). Total RNA of 2 μg was used to synthesize the first-strand cDNA with an oligo(dT) primer, and RT-qPCR was performed as reported previously (Cao et al., 2012). The maize ubiquitin gene was used to normalize transcript amounts of all samples. The experiments were performed at least three times. The primers used for RT-qPCR analysis are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

Infiltration, Antibodies, Western-Blot Analysis, and Protein Degradation Assay

The recombinant plasmids used for agroinfiltration were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. For agroinfiltration, the transformed agrobacteria were cultured, pelleted, and then resuspended in infiltration buffer (10 mm MgCl2, 10 mm MES, and 100 μm acetosyringone, pH 5.6). After 2 to 4 h of incubation at room temperature, the culture was diluted to an optical density of 0.5 at 600 nm. Appropriate agrobacterial cultures were used to infiltrate the leaves of 4-week-old N. benthamiana plants. Tomato bushy stunt virus p19, as a strong silencing suppressor, was used to enhance protein expression unless described otherwise. The protein extraction and western-blot assay were performed as described previously (Cao et al., 2012). Monoclonal antibodies of HA and GFP (CW0260 and CW0258; Kangweishiji Biotechnology) were used at a dilution of 1:5,000. Monoclonal antibodies of c-Myc and Flag (A5598 and A8592; Sigma) were used at a dilution of 1:10,000. Polyclonal antibody of SCMV CP was used at a dilution of 1:5,000. For the protein degradation assay, 10 mm MgCl2 buffer containing 1% DMSO (control) or an equal volume of DMSO with 50 μm MG132 (Sigma) for inhibition of the 26S proteasome was infiltrated into leaves 12 h before samples were collected. Double distilled water (control) or containing 5 mm 3-methyladenine (Sigma) for inhibition of autophagy also was infiltrated into leaves 12 h before samples were collected.

Confocal Microscopy

For BiFC and the subcellular localization assay in N. benthamiana leaves, maize leaves, and maize protoplasts, fluorescence signals were visualized using an Olympus FluoView 1000 confocal microscope (Olympus) equipped with Olympus FluoView software FV10-ASW 4.0 Viewer. Images of YFP, GFP, and DsRed2 fusions were captured in the green (EYFP), green (EGFP), and red (DsRed2) channels, respectively. Images of chlorophyll autofluorescence were captured in the red (Alexa Fluor 633) channel. In addition, for the subcellular localization assay in N. benthamiana leaves and maize protoplasts, fluorescence signals were visualized using a Nikon Eclipse TE 2000-E laser-scanning confocal microscope equipped with Nikon EZ-C1 FreeViewer 3.00. The fluorescence of GFP and DsRed2 was excited at 488 and 543 nm, respectively. The images were captured at 72 h post agroinfiltration and processed using Adobe Photoshop. At least two independent experiments were performed.

Maize Protoplast Isolation and Transfection

Maize protoplast isolation and transfection were performed as described previously (Sheen, 1991; Zhu et al., 2014).

Targeted Site-Directed Mutagenesis of ZmVDEm

The primers containing one or two nucleotide substitutions (Supplemental Table S1) were designed for amplification of the entire plasmid. The targeted exchange of one or two bases in the plasmid of pGADT7-ZmVDEm was performed by PCR using PrimeSTAR HS DNA Polymerase (Takara Bio). The resulting PCR products were digested with DMT enzyme, purified, and introduced into DMT chemically competent cells (TransGen Biotech) to degrade the methylated template plasmid. The transformants were selected and sequenced for further studies.

GFP Imaging and RNA Gel-Blot Analysis

GFP fluorescence was visualized using a long-wavelength UV light (Black Ray model B 100AP; Ultraviolet Products) and photographed with a Canon PowerShot SX20 IS digital camera 3 d post agroinfiltration. Each assay consisted of at least 50 individual leaves from three independent experiments each with 8 or 10 biological replicates. Each replicate consisted of two or three leaves.

The N. benthamiana leaves infiltrated with the indicated constructs were sampled and pooled for protein and total RNA extraction at 3 dpi. Two independent experiments were conducted with 10 biological replicates each. RNA samples of 10 to 15 µg were used to detect GFP mRNA by northern-blot analyses. Northern blotting was performed with [α-32P]dCTP randomly labeled cDNA probes, which were from 62 to 673 nucleotides of the GFP sequences. The probes were labeled, and the blots were probed and washed as reported previously (Xia et al., 2016). Approximately 30-µg total RNA samples were prepared to detect GFP siRNAs, and the blots were probed and washed as described previously (Xia et al., 2014). Probe sequences used for detection of the GFP siRNAs are shown in Supplemental Table S3.

Particle Bombardment

The preparation of maize (B73) tissue samples (mock and SCMV inoculated) was conducted as described previously (Kirienko et al., 2012). Particle bombardment was performed as described previously (Zhu et al., 2014) with slight modifications. The pellets of gold-plasmid DNA particles were resuspended by 10 μL of ethanol solution and transferred to macrocarriers (Bio-Rad) for subsequent bombardment. All bombardments were performed with a PDS-1000/He system (Bio-Rad) as instructed. Tissue helium pressure at the tank was regulated at 1,500 pounds per square inch. Vacuum pressure within the chamber was allowed to reach at least 26 to 28 inches of mercury prior to firing. After bombardment, leaf tissue was allowed to recover for 24 to 36 h at 25°C in the dark prior to analysis.

BMV-Induced Gene Silencing in Maize

Infectious transcripts from pC-BMVA/G and pC-BMVA/G/VDE harboring a 180-bp fragment of ZmVDE amplified from the 3ʹ untranslated region of the gene were prepared by in vitro transcription using T3 DNA-dependent RNA polymerase (Promega). The experiment was conducted as described previously with some modifications (Ding et al., 2006; Cao et al., 2012). The RNA transcripts were rub inoculated to N. benthamiana leaves at the seven-leaf stage. At 5 dpi, after verification of the maintenance of foreign insertions in BMV virus-induced gene silencing vectors with primers listed in Supplemental Table S2, the crude extracts of the harvested N. benthamiana leaves were rub inoculated to the first true leaves of 1-week-old maize (Va35) plants. The second upper leaves systemically infected by BMV were challenge inoculated with SCMV at 10 dpi. The first systemically infected leaves (by SCMV) of each assayed plants were harvested at 6 dpi and used to analyze the silencing efficiency of ZmVDE and SCMV RNA and CP protein accumulation.

Maize Chloroplast Isolation and Protein Extraction

Maize chloroplasts were isolated from maize (B73) plants as described previously (Voelker and Barkan, 1995). Briefly, mock- and SCMV-inoculated maize kernels by vascular puncture inoculation and healthy maize kernels were grown under day/night cycles (as described above) until the third leaf was expanded. Approximately 9 g of maize seedling leaves was used for chloroplast isolation. The reconstitution experiments were performed using chloroplasts isolated from healthy maize plants mixed with the supernatant of a chloroplast preparation from the same amount of SCMV-infected maize tissues as described previously (Gunasinghe and Berger, 1991) to rule out the contamination by cytosol proteins. For chloroplasts from reconstitution experiments and SCMV-infected maize leaves, thermolysin (Promega) treatment (Cline et al., 1984) was conducted as described previously to digest the proteins attached to the surface of chloroplasts. Chloroplast pellets of all samples were used for protein extraction as described previously (Fan et al., 2009). The extracted proteins were analyzed by western blotting with rabbit polyclonal HC-Pro antibody.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under the following accession numbers: ZmVDE (EU956472), SbVDE (XM_002446236), OsVDE (NM_001059127), and the ubiquitin gene (U29159.1).

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Verification of protein expression in yeast cells.

Supplemental Figure S2. ZmVDEm only interacts with HC-Pro among 11 SCMV-encoded proteins.

Supplemental Figure S3. Amino acid sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis of ZmVDE and its homologous proteins from other plant species.

Supplemental Figure S4. Identification of the amino acid within ZmVDEm essential for interaction with SCMV HC-Pro in yeast cells.

Supplemental Figure S5. Subcellular localization of different forms of ZmVDE and the mutant ZmVDEmQ292A in N. benthamiana leaves.

Supplemental Figure S6. ZmVDEp-GFP localized in the chloroplasts and stromules in the presence of SCMV HC-Pro.

Supplemental Figure S7. HC-Pro protein was not detected in the chloroplasts of SCMV-infected maize leaves.

Supplemental Figure S8. Determination of the subcellular localization of GFP-ZmVDEm and its mutant GFP-ZmVDEmQ292A in N. benthamiana leaves.

Supplemental Figure S9. ZmVDE did not relocalize to MDMV HC-Pro- and PenMV HC-Pro-containing aggregate bodies in N. benthamiana leaves.

Supplemental Figure S10. OsVDEm-GFP did not relocalize to aggregate bodies in the presence of SCMV HC-Pro, MDMV HC-Pro, or PenMV HC-Pro.

Supplemental Figure S11. ZmVDE relocalizes to SCMV HC-Pro-containing aggregate bodies but does not affect their quantity.

Supplemental Figure S12. Detection of SCMV accumulation in maize tissues to be used for microprojectile bombardment with plasmids expressing GFP, ZmVDEm-GFP, ZmVDEp-GFP, GFP-ZmVDEp, or ZmVDEmQ292A-GFP.

Supplemental Figure S13. The tags fused to the N terminus of SCMV HC-Pro have no obvious effect on its RSS activity.

Supplemental Figure S14. ZmVDE has no obvious effect on the local RSS activity of p19.

Supplemental Figure S15. ZmVDE did not degrade HC-Pro via ubiquitination or the autophagy pathway.

Supplemental Table S1. Constructs and primer sets used in this study.

Supplemental Table S2. Primers used for PCR analyses.

Supplemental Table S3. Probes for northern blotting of small RNAs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ping Yang (Institute of Crop Sciences, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences) for providing the plastid marker, Dr. T. Meulia (Ohio State University) for providing the full-length cDNA clone of MDMV-OH1, Dr. Richard S. Nelson (Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation) for providing the BMV virus-induced gene silencing vector, Dr. Andrew O. Jackson (University of California, Berkeley) for providing the pGD vector, and Dr. Jörg Kudla (Universität Münster) for providing the BiFC vectors.

Footnotes

This research was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 31571980) and the Ministry of Education (111 Project B13006).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Abbink TEM, Peart JR, Mos TNM, Baulcombe DC, Bol JF, Linthorst HJM (2002) Silencing of a gene encoding a protein component of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II enhances virus replication in plants. Virology 295: 307–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albar L, Bangratz-Reyser M, Hébrard E, Ndjiondjop MN, Jones M, Ghesquière A (2006) Mutations in the eIF(iso)4G translation initiation factor confer high resistance of rice to Rice yellow mottle virus. Plant J 47: 417–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anandalakshmi R, Marathe R, Ge X, Herr JM Jr, Mau C, Mallory A, Pruss G, Bowman L, Vance VB (2000) A calmodulin-related protein that suppresses posttranscriptional gene silencing in plants. Science 290: 142–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anandalakshmi R, Pruss GJ, Ge X, Marathe R, Mallory AC, Smith TH, Vance VB (1998) A viral suppressor of gene silencing in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 13079–13084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballut L, Drucker M, Pugnière M, Cambon F, Blanc S, Roquet F, Candresse T, Schmid HP, Nicolas P, Gall OL, et al. (2005) HcPro, a multifunctional protein encoded by a plant RNA virus, targets the 20S proteasome and affects its enzymic activities. J Gen Virol 86: 2595–2603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat S, Folimonova SY, Cole AB, Ballard KD, Lei Z, Watson BS, Sumner LW, Nelson RS (2013) Influence of host chloroplast proteins on Tobacco mosaic virus accumulation and intercellular movement. Plant Physiol 161: 134–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobik K, Burch-Smith TM (2015) Chloroplast signaling within, between and beyond cells. Front Plant Sci 6: 781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boualem A, Dogimont C, Bendahmane A (2016) The battle for survival between viruses and their host plants. Curr Opin Virol 17: 32–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cañizares MC, Lozano-Durán R, Canto T, Bejarano ER, Bisaro DM, Navas-Castillo J, Moriones E (2013) Effects of the crinivirus coat protein-interacting plant protein SAHH on post-transcriptional RNA silencing and its suppression. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 26: 1004–1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canto T, Uhrig JF, Swanson M, Wright KM, MacFarlane SA (2006) Translocation of Tomato bushy stunt virus P19 protein into the nucleus by ALY proteins compromises its silencing suppressor activity. J Virol 80: 9064–9072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Shi Y, Li Y, Cheng Y, Zhou T, Fan Z (2012) Possible involvement of maize Rop1 in the defence responses of plants to viral infection. Mol Plant Pathol 13: 732–743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan JL, Kumar AS, Park E, Padmanabhan MS, Hoban K, Modla S, Czymmek K, Dinesh-Kumar SP (2015) Chloroplast stromules function during innate immunity. Dev Cell 34: 45–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan JL, Mamillapalli P, Burch-Smith TM, Czymmek K, Dinesh-Kumar SP (2008) Chloroplastic protein NRIP1 mediates innate immune receptor recognition of a viral effector. Cell 132: 449–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington JC, Cary SM, Parks TD, Dougherty WG (1989) A second proteinase encoded by a plant potyvirus genome. EMBO J 8: 365–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SH, Bugos RC, Sun WH, Yamamoto HY (2000) Antisense suppression of violaxanthin de-epoxidase in tobacco does not affect plant performance in controlled growth conditions. Photosynth Res 64: 95–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Cao Y, Li Y, Xia Z, Xie J, Carr JP, Wu B, Fan Z, Zhou T (2017) Identification of differentially regulated maize proteins conditioning Sugarcane mosaic virus systemic infection. New Phytol 215: 1156–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Galvão RM, Li M, Burger B, Bugea J, Bolado J, Chory J (2010) Arabidopsis HEMERA/pTAC12 initiates photomorphogenesis by phytochromes. Cell 141: 1230–1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Jolley B, Caldwell C, Gallie DR (2014) Eukaryotic translation initiation factor eIFiso4G is required to regulate violaxanthin de-epoxidase expression in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem 289: 13926–13936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng SF, Huang YP, Chen LH, Hsu YH, Tsai CH (2013) Chloroplast phosphoglycerate kinase is involved in the targeting of Bamboo mosaic virus to chloroplasts in Nicotiana benthamiana plants. Plant Physiol 163: 1598–1608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng YQ, Liu ZM, Xu J, Zhou T, Wang M, Chen YT, Li HF, Fan ZF (2008) HC-Pro protein of sugar cane mosaic virus interacts specifically with maize ferredoxin-5 in vitro and in planta. J Gen Virol 89: 2046–2054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline K, Werner-Washburne M, Andrews J, Keegstra K (1984) Thermolysin is a suitable protease for probing the surface of intact pea chloroplasts. Plant Physiol 75: 675–678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley MB, Pathirana S, Wu HJ, Kachroo P, Klessig DF (2000) Members of the Arabidopsis HRT/RPP8 family of resistance genes confer resistance to both viral and oomycete pathogens. Plant Cell 12: 663–676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culver JN, Padmanabhan MS (2007) Virus-induced disease: altering host physiology one interaction at a time. Annu Rev Phytopathol 45: 221–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]