Two plasmodesmata-localized potyviral proteins of Turnip mosaic virus compose a minimum complex serving as a docking point for plasmodesmata targeting and intercellular movement of replication vesicles.

Abstract

Plant viruses move from the initially infected cell to adjacent cells through plasmodesmata (PDs). To do so, viruses encode dedicated protein(s) that facilitate this process. How viral proteins act together to support the intercellular movement of viruses is poorly defined. Here, by using an infection-free intercellular vesicle movement assay, we investigate the action of CI (cylindrical inclusion) and P3N-PIPO (amino-terminal half of P3 fused to Pretty Interesting Potyviridae open reading frame), the two PD-localized potyviral proteins encoded by Turnip mosaic virus (TuMV), in the intercellular movement of the viral replication vesicles. We provide evidence that CI and P3N-PIPO are sufficient to support the PD targeting and intercellular movement of TuMV replication vesicles induced by 6K2, a viral protein responsible for the generation of replication vesicles. 6K2 interacts with CI but not P3N-PIPO. When this interaction is impaired, the intercellular movement of TuMV replication vesicles is inhibited. Furthermore, in transmission electron microscopy, vesicular structures are observed in connection with the cylindrical inclusion bodies at structurally modified PDs in cells coexpressing 6K2, CI, and P3N-PIPO. CI is directed to PDs through its interaction with P3N-PIPO. We hypothesize that CI serves as a docking point for PD targeting and the intercellular movement of TuMV replication vesicles. This work contributes to a better understanding of the roles of different viral proteins in coordinating the intercellular movement of viral replication vesicles.

Turnip mosaic virus (TuMV) is a member of the Potyviridae family (Nicolas and Laliberté, 1992). It infects a broad spectrum of plants of the Brassica genus, including the economically important oilseed rape (Brassica napus ssp. oleifera). The genome of TuMV is monopartite positive single-stranded RNA (Nicolas and Laliberté, 1992), which encodes for at least 11 different mature proteins (Nicolas and Laliberté, 1992; Chung et al., 2008). It has been shown that, upon infection, TuMV induces the rearrangement of the endomembrane system and the formation of small vesicles through the action of a transmembrane viral protein called 6K2 (Nicolas and Laliberté, 1992; Beauchemin and Laliberté, 2007; Cotton et al., 2009; Grangeon et al., 2012). 6K2-induced vesicles contain viral RNA and several replication-related viral and host proteins (Beauchemin et al., 2007; Dufresne et al., 2008). Moreover, the 6K2 vesicles also contain RNA polymerase and double-stranded viral RNAs, suggesting that the 6K2-tagged vesicular structures are viral RNA replication sites (Wan et al., 2015).

The 6K2 replication vesicles also serve as a vehicle for the cell-to-cell spread of TuMV (Grangeon et al., 2013). The 6K2-induced replication vesicles are formed from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in a COPII-COPI-dependent manner (Cotton et al., 2009) and then bud off from the ER at the ER exit sites (Cotton et al., 2009). Once budding off, these replication vesicles traffic intracellularly along microfilaments (Cotton et al., 2009) and eventually reach plasmodesmata (PD), from where they ultimately cross into the uninfected neighboring cell (Grangeon et al., 2013). Interestingly, the 6K2-induced replication vesicles can be formed through the ectopic expression of 6K2, but these vesicles are incapable of moving intercellularly in the absence of TuMV infection (Grangeon et al., 2013), indicating that additional viral proteins are required for its intercellular movement.

It is commonly accepted that plant viruses spread intercellularly through the PD. However, viral particles are too large to pass through PD. Most plant viruses encode for at least one protein that increases the size exclusion limit (SEL) of PD to allow the passage of viral particles from cell to cell (Brandenburg and Zhuang, 2007; Benitez-Alfonso et al., 2010; Niehl and Heinlein, 2011; Ritzenthaler, 2011; Ueki and Citovsky, 2011). In the case of TuMV, there are at least three viral proteins involved in its cell-to-cell movement: P3N-PIPO (P3-N-terminal-Pretty Interesting Potyviral Open Reading Frame), CI (Cylindrical Inclusion) helicase, and CP (Coat Protein). P3N-PIPO localizes to PD and modifies the SEL of PD to facilitate its own and potyvirus intercellular movement (Vijayapalani et al., 2012). It has been described that, different from the PD targeting of 6K2-induced replication vesicles, the PD targeting of P3N-PIPO requires a functional COPII-COPI transport system but not actin microfilaments or myosin motors (Wei et al., 2010b). Additionally, a plasma membrane-localized cation binding protein has been shown to be involved in the targeting of P3N-PIPO to the PD (Vijayapalani et al., 2012). The CI helicase was shown to localize to PD, possibly through its physical interaction with P3N-PIPO (Wei et al., 2010b). Mutations in the CI helicase outside of the conserved helicase domains from the related potyvirus Tobacco etch virus severely delay or completely disrupt its intercellular movement (Carrington et al., 1998). The CP also localizes to the PD together with CI and P3N-PIPO during TuMV infection (Wei et al., 2010b).

Despite the study of the involvement of these proteins in the cell-to-cell movement of TuMV, how these proteins act together to support the intercellular spread of TuMV is not clear. In this article, we developed an infection-free intercellular 6K2 vesicle movement assay with the aim of studying the action of CI and P3N-PIPO in the intercellular movement of 6K2-induced replication vesicles. We found that P3N-PIPO and CI are necessary and sufficient to facilitate the intercellular movement of the 6K2-induced replication vesicles. P3N-PIPO and CI also are sufficient to target the 6K2 vesicles to PD when expressed together, although P3N-PIPO and 6K2 take different routes to reach PD. 6K2 can interact physically with CI but not P3N-PIPO; furthermore, a mutated CI that is unable to interact with 6K2 but still interacts with P3N-PIPO failed to support the intercellular movement of 6K2. The evidence found suggests that CI and P3N-PIPO of TuMV compose a minimal complex required for the intercellular movement of 6K2 viral replication vesicles and that CI serves as a docking point between the P3N-PIPO-modified PD and the 6K2-coated replication vesicles.

RESULTS

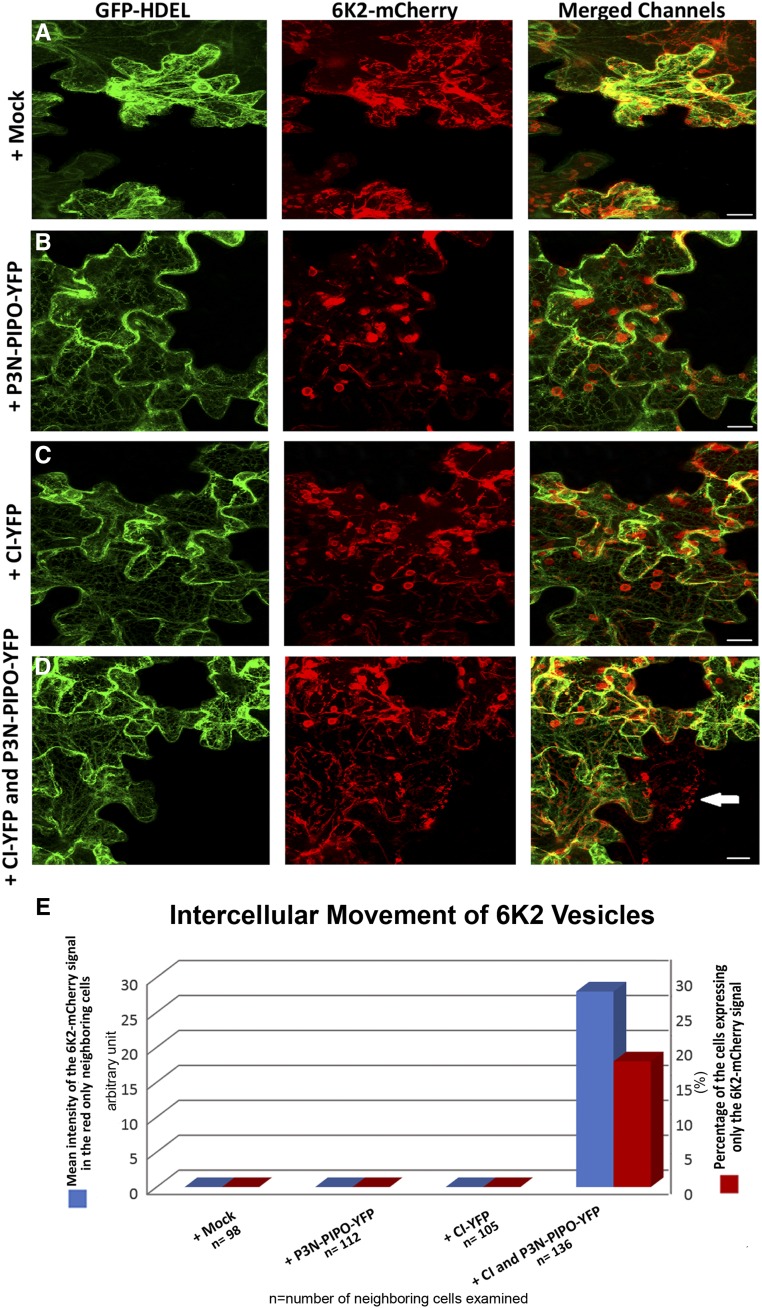

CI and P3N-PIPO Are Necessary and Sufficient to Facilitate the Intercellular Movement of 6K2 Vesicles

Since both P3N-PIPO and CI proteins have been shown to play important roles in the intercellular spread of TuMV (Wei et al., 2010b; Vijayapalani et al., 2012), we wondered if CI and P3N-PIPO, when expressed alone, could facilitate the intercellular movement of 6K2 vesicles in the absence of TuMV infection. To test this, the dual cassette construct pCambia/6K2-mCherry/GFP-HDEL (Grangeon et al., 2013) was expressed alone, together with CI fused to YFP (CI-YFP), P3N-PIPO fused to YFP (P3N-PIPO-YFP), or both. The intercellular movement of 6K2-mCherry is observed in cells emitting red fluorescence only, since the ER marker GFP-HDEL cannot move from cell to cell (Grangeon et al., 2013). When the dual cassette construct was expressed alone (Fig. 1A) or coexpressed with either P3N-PIPO-YFP (Fig. 1B) or CI-YFP (Fig. 1C), we never observed cells that expressed 6K2-mCherry red fluorescence only, indicating that there was no cell-to-cell movement of 6K2-mCherry (Fig. 1, A–C and E). Interestingly when the dual cassette construct was coexpressed with both CI-YFP and P3N-PIPO-YFP, 6K2-mCherry only fluorescence was detected (Fig. 1, D, arrow, and E), indicating that there was intercellular movement of 6K2-mCherry. Of 136 neighboring cells we examined, we found that 29 cells (∼22%) showed 6K2-mCherry signal only (Fig. 1E). The mean intensity of the 6K2-mCherry signal in the red-only neighboring cells was measured to be about 27 in arbitrary units (Fig. 1E), using the Imaris image analysis. No neighboring cell showing 6K2-mCherry signals was observed in leaves expressing the dual construct pCambia/6K2-mCherry/GFP-HDEL alone (Fig. 1, A and E) or with either P3N-PIPO-YFP (Fig. 1, B and E) or CI-YFP (Fig. 1, C and E). These results indicated that the presence of both CI and P3N-PIPO facilitates the intercellular movement of 6K2.

Figure 1.

CI and P3N-PIPO are necessary and sufficient to support the intercellular movement of 6K2 vesicles. A to D, Expression of the dual construct pCambia/6K2-mCherry/GFP-HDEL alone (A), with P3N-PIPO-YFP (B), with CI-YFP (C), or with both CI-YFP and P3N-PIPO-YFP (D). The white arrow in D points to a cell showing red fluorescence only. Bars = 10 μm. E, Quantification of 6K2 intercellular movement by counting the percentage of neighboring cells showing only 6K2-mCherry signal and measuring the mean intensity of 6K2-mCherry signals in red-only areas of the neighboring cells (in arbitrary units) with Imaris image-analysis software (n = number of neighboring cells examined).

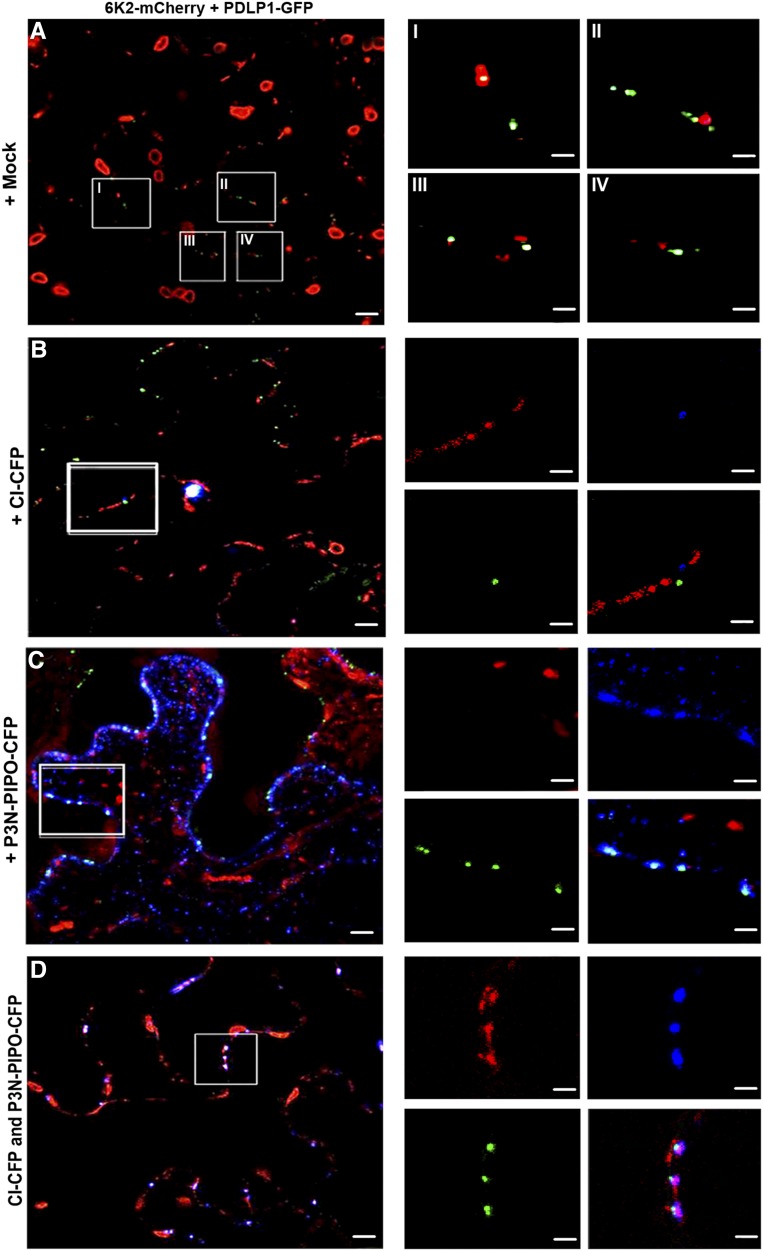

CI and P3N-PIPO Support the PD Targeting of 6K2

One explanation for both proteins being required for the intercellular movement of 6K2 vesicles is that they facilitate the targeting of 6K2 to PDs. To verify this, the localization of 6K2-mCherry to PDLP1-GFP, a PD marker protein, was examined when coexpressed with CI-CFP, P3N-PIPO-CFP, or both. Colocalization was hardly seen between 6K2-mCherry and PDLP1-GFP when CI-CFP and P3N-PIPO-CFP were not present (Fig. 2A) or were present individually (Fig. 2, B and C). However, colocalization of 6K2-mCherry with PDLP1-GFP was seen when both CI-CFP and P3N-PIPO-CFP were expressed together (Fig. 2D). To confirm these results, the Pearson’s correlation coefficient between 6K2-mCherry and PDLP1-GFP was measured using the ImageJ-based open-source processing package Fiji, as described by Breeze et al. (2016). Pearson correlation coefficients between sets of data are a measurement of how well they are linearly related. The Pearson’s correlation coefficients between 6K2-mCherry and PDLP1-GFP in cells with the expression of 6K2-mCherry only (Fig. 3A, Ectopic), in cells with 6K2-mCherry coexpressed with both CI-CFP and P3N-PIPO-CFP (Fig. 3A, CI & PIPO), and in cells infected by TuMV (Fig. 3A, Infection) are presented in Figure 3A. The results indicate that the colocalization between 6K2-mCherry and PDLP1-GFP was significantly higher when coexpressed with CI and P3N-PIPO compared with the expression of 6K2-mCherry alone (Fig. 3A). We also examined the localization of 6K2 with PDLP1 during TuMV infection (Fig. 3B). The colocalization of 6K2-mCherry with PDLP1-GFP (Fig. 3B, I and II) was higher during TuMV infection than what was observed in cells with the ectopic expression of 6K2-mCherry alone (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, the localization of 6K2-mCherry to PD was not significantly different between the coexpression with both CI-CFP and P3N-PIPO-CFP and during TuMV infection (Fig. 3A). These results suggest that these two proteins are sufficient to direct the 6K2 vesicles to PD.

Figure 2.

CI and P3N-PIPO support the PD targeting of 6K2 vesicles. Colocalization of 6K2-mCherry is shown with PDLP1-GFP-labeled PD during ectopic expression of 6K2-mCherry alone (A) or when coexpressed with CI-CFP (B), P3N-PIPO-CFP (C), or both CI-CFP and P3N-PIPO-CFP (D). Insets (I–IV) for A show four selected regions in A; insets for B to D are color-separated images for selected regions in B to D, respectively. Bars on the left = 4 μm; bars on the right (high-magnification images) = 2 μm.

Figure 3.

CI and P3N-PIPO are sufficient to support the PD targeting of 6K2 vesicles. A, Quantification of the colocalization between 6K2-mCherry and PDLP1-GFP when expressed alone (Ectopic), when coexpressed with both CI-CFP and P3N-PIPO-CFP (+ CI & PIPO), or during infection (Infection). The y axis shows the Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PCC; Student’s t test, n = 20, P > 0.05). Columns with a single asterisk show that the t test for those rows is statistically significant. B, Colocalization of 6K2-mCherry with PDLP1-GFP-labeled PD during TuMV infection. Bar on the left = 15 μm; bars on the right (high-magnification images) = 5 μm.

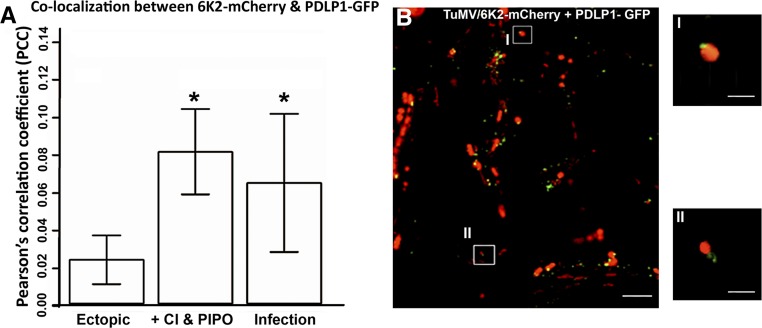

Targeting of P3N-PIPO to PD, But Not the Intracellular Motility of 6K2, Requires Functional Post-Golgi Trafficking

The PD targeting of P3N-PIPO requires a functional COPII-COPI transport system but not actin microfilaments or myosin motors (Wei et al., 2010b). However, the intracellular trafficking of TuMV replication vesicles requires actin microfilaments and myosin motors (Cotton et al., 2009; Wei et al., 2010a). Therefore, we hypothesize that the PD targeting of P3N-PIPO and the intracellular motility of 6K2 take different intracellular pathways. To test this, a dominant negative mutant of the small GTPase RabE1d(NI) was used. RabE1d is involved in the post-Golgi trafficking toward the plasma membrane (Zheng et al., 2005; Speth et al., 2009). The mutated RabE1d(NI) inhibits the intercellular movement of TuMV but not its replication (Agbeci et al., 2013). We first tested whether the localization of the fluorescently labeled proteins P3N-PIPO-CFP and CI-CFP can be altered or not when coexpressed with RabE1d(NI). Each of these fluorescent fusion proteins was coexpressed with either RabE1d(WT) or RabE1d(NI), and its localization was examined at 3 d postinfiltration (dpi) as described (Zheng et al., 2005). The protein P3N-PIPO-CFP produced punctate structures when coexpressed with the wild-type version of RabE1d (Fig. 4A), as described previously (Wei et al., 2010b), but it showed a continuous distribution resembling the plasma membrane when coexpressed with RabE1d(NI) (Fig. 4B). This suggested that the correct PD targeting of P3N-PIPO requires a functional post-Golgi trafficking pathway. Interestingly, the localization of CI-CFP showed no noticeable differences when coexpressed either with the wild type or the dominant negative version of RabE1d (Fig. 4, C and D).

Figure 4.

Transport of P3N-PIPO takes a post-Golgi transport-dependent secretory pathway. A and B, Localization of P3N-PIPO-CFP when coexpressed with either wild-type (WT) RabE1d (A) or the dominant negative RabE1d(NI) (B). C and D, Localization of CI-CFP when coexpressed with either wild-type RabE1d (C) or the dominant negative RabE1d(NI) (D). Bars = 5 μm.

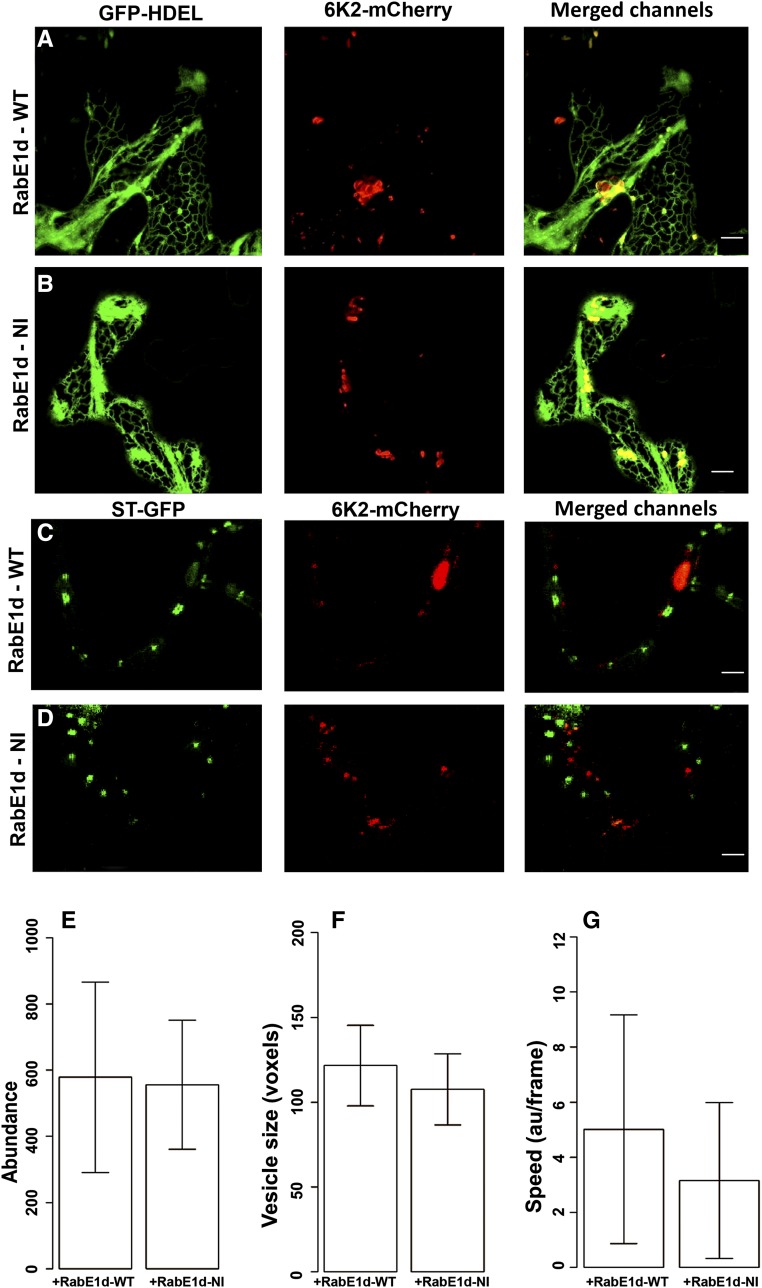

We next examined the formation or intracellular transport of 6K2 vesicles in the presence of RabE1d(NI). 6K2-mCherry was only colocalized with GFP-HDEL in the globular structure but not in ER tubules when coexpressed with either RabE1d (Fig. 5A) or RabE1d-(NI) (Fig. 5B), as described previously (Grangeon et al., 2012). Similarly, 6K2-mCherry did not fully colocalize with ST-GFP when coexpressed with either RabE1d (Fig. 5C) or its dominant negative version (Fig. 5D). These results indicated that the formation or intracellular transport of 6K2 vesicles is not affected by the presence of RabE1d(NI). To further confirm this, the abundance, apparent size, and speed of movement of 6K2 vesicles were quantified when coexpressed with either RabE1d or the dominant negative RabE1d(NI). There were no significant differences in the abundance (Fig. 5E), apparent size (Fig. 5F), and speed of movement (Fig. 5G) of the 6K2 vesicles when coexpressed with RabE1d(NI) compared with RabE1d. Taken together, these results indicate that, unlike the transport of P3N-PIPO, the formation and intracellular motility of 6K2 vesicles do not require a functional post-Golgi trafficking.

Figure 5.

Intracellular motility of 6K2 does not require functional post-Golgi trafficking. A and B, Colocalization of 6K2-mCherry relative to the ER marker GFP-HDEL when coexpressed with either RabE1d (A) or the dominant negative RabE1d(NI) (B). Bars = 10 μm. C and D, Localization of 6K2-mCherry relative to the Golgi marker ST-GFP when coexpressed with either RabE1d (C) or the dominant negative RabE1d(NI) (D). Bars = 5 μm. E to G, Quantification of 6K2-mCherry-formed vesicle abundance per single cell (E; Student’s t test, n = 10, P > 0.05), average vesicle size (F; Student’s t test, n = 10, P > 0.05), and average movement speed of the vesicles (G; Student’s t test, n = 5, P > 0.05). The unit au/frame refers to the line profiles of fluorescence intensity in arbitrary units per frame. WT, Wild type.

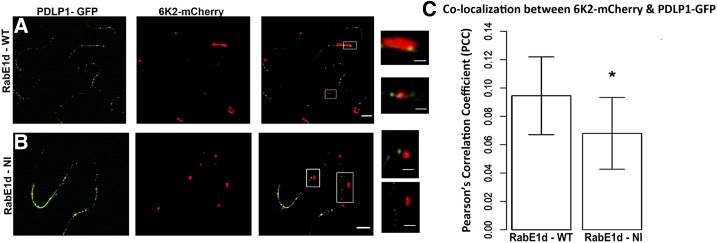

Inhibition of RabE1d-Mediated Post-Golgi Transport Affects PD Targeting of 6K2 Vesicles

Although the expression of the dominant negative RabE1d(NI) does not affect the intracellular motility of 6K2 vesicles, it disrupts the correct PD localization of P3N-PIPO. Therefore, we wondered if the coexpression of RabE1d(NI) would affect the targeting of 6K2-mCherry to PD. Since coexpressing five different constructs [P3N-PIPO, CI, 6K2, PDLP1, and either RabE1d or RabE1d(NI)] in the same cell is difficult, the effect of the coexpression of RabE1d(NI) in the PD targeting of 6K2 vesicles was examined during TuMV infection. For this purpose, the colocalization of 6K2-mCherry and PDLP1-GFP was observed and quantified when coexpressed with either RabE1d (Fig. 6, A and C) or RabE1d(NI) (Fig. 6, B and C) during TuMV infection. We found that there was a statistically significant decrease of the colocalization between 6K2-mCherry and PDLP1-GFP when the dominant negative RabE1d(NI) was expressed (Fig. 6C). This evidence supports the idea that P3N-PIPO plays a role in the targeting of 6K2 vesicles to PD.

Figure 6.

PD targeting of 6K2 is affected when a functional post-Golgi trafficking pathway is impaired. A and B, Colocalization of 6K2-mCherry with PDLP1-GFP-labeled PD during TuMV infection when coexpressed with either RabE1d (A) or the dominant negative RabE1d(NI) (B). Bars on the left = 5 μm; bars on the right (high-magnification images) = 1 μm. C, Quantification of the colocalization between 6K2-mCherry and PDLP1-GFP during infection when coexpressed with either RabE1d or the dominant negative RabE1d(NI). The y axis shows the Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PCC; Student’s t test, n = 20, P < 0.05). Column with a single asterisk shows that the t test for that row is statistically significant. WT, Wild type.

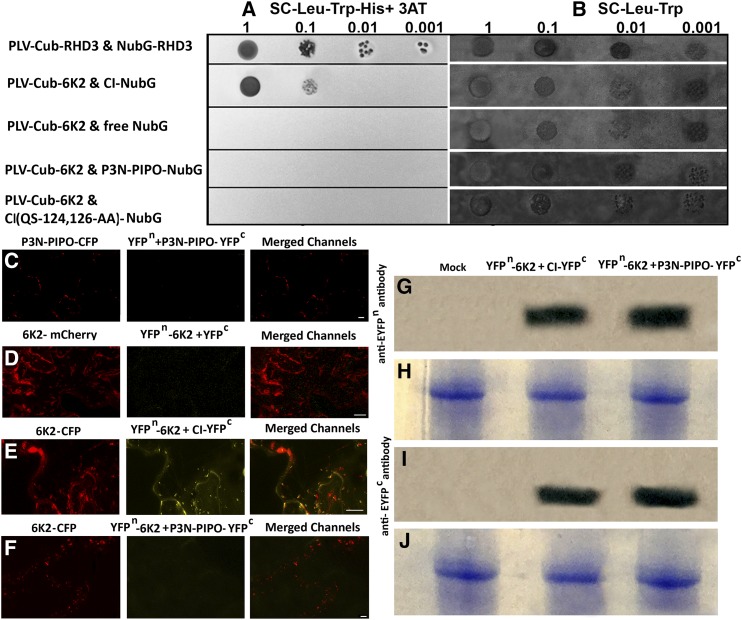

6K2 Interacts Physically with CI But Not P3N-PIPO

Since P3N-PIPO and CI are necessary and sufficient to support the PD targeting and intercellular movement of 6K2 vesicles, we wondered if 6K2 interacts physically with either of these proteins. The interactions between 6K2 and either P3N-PIPO or CI were first tested in a split ubiquitin-based yeast two-hybrid system (Y2H-SUS). PLV-Cub-6K2 was found to interact with CI-NubG but not with P3N-PIPO-NubG (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7.

6K2 interacts with CI but not P3N-PIPO. A and B, Y2H-SUS assay of PLV-Cub-RHD3 and NubG-RHD3 (used as a positive control), PLV-Cub-6K2 and CI-NubG, PLV-Cub-6K2 and free NubG (used as a negative control), PLV-Cub-6K2 and P3N-PIPO-NubG, and PLV-Cub-6K2 and CI(QS-124,126-AA)-NubG. In A, the mated cells were grown in SC-Leu-Trp-His + 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (3AT), and in B, the mated cells were grown in SC-Leu-Trp as mating controls. C to F, BiFC analysis of unfused YFPn and P3N-PIPO-YFPc (yellow) with ectopically expressed P3N-PIPO-CFP (red; C), YFPn-6K2 and unfused YFPc (yellow) with ectopically expressed 6K2-mCherry (red; D), YFPn-6K2 and CI-YFPc (yellow) with coexpression of ectopic 6K2-CFP (red; E), and YFPn-6K2 and P3N-PIPO-YFPc (yellow) with coexpression of ectopic 6K2-CFP (red; F). Bars = 10 μm. G to J, Immunoblots of leaves expressing either YFPn-6K2 and YFPc-CI or YFPn-6K2 and P3N-PIPO-YFPc using anti-EYFPn rabbit serum (G) and anti-EYFPc rabbit serum (I). The lower gels (H for G and J for I) indicate protein loading by Coomassie Blue staining.

The interaction of 6K2 with CI and P3N-PIPO was further assessed with bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) in plant cells. When the N-terminal half of YFP (YFPn)-fused 6K2 (YFPn-6K2) was coexpressed with the C-terminal half of YFP (YFPc)-fused CI (YFPc-CI), YFP fluorescence was reestablished (Fig. 7E), while no YFP fluorescence was discerned when YFPn-6K2 was coexpressed with YFPc-fused P3N-PIPO (P3N-PIPO-YFPc; Fig. 7F). When YFPn-6K2 was coexpressed with unfused YFPc (Fig. 7D) or P3N-PIPO-YFPc was coexpressed with YFPn (Fig. 7C), no YFP signals were detected. Interestingly, coexpression of YFPn-6K2 and YFPc-CI used for BiFC with CFP-6K2 (red) revealed that YFP fluorescent punctae largely colocalized with the CFP fluorescence of 6K2 vesicles (Fig. 7E). This suggests that 6K2 and CI interact mainly at the sites of 6K2 vesicles. To demonstrate that the proteins shown not to interact (YFPn-6K2 and P3N-PIPO-YFPc) were expressed at similar levels to proteins that are shown to interact (YFPn-6K2 and YFPc-CI), a western-blot assay was conducted with anti-EYFPn and anti-EYFPc sera. As can be seen in Figure 7, G to I, the proteins YFPn-6K2 and P3N-PIPO-YFPc and the proteins YFPn-6K2 and YFPc-CI were expressed at similar levels.

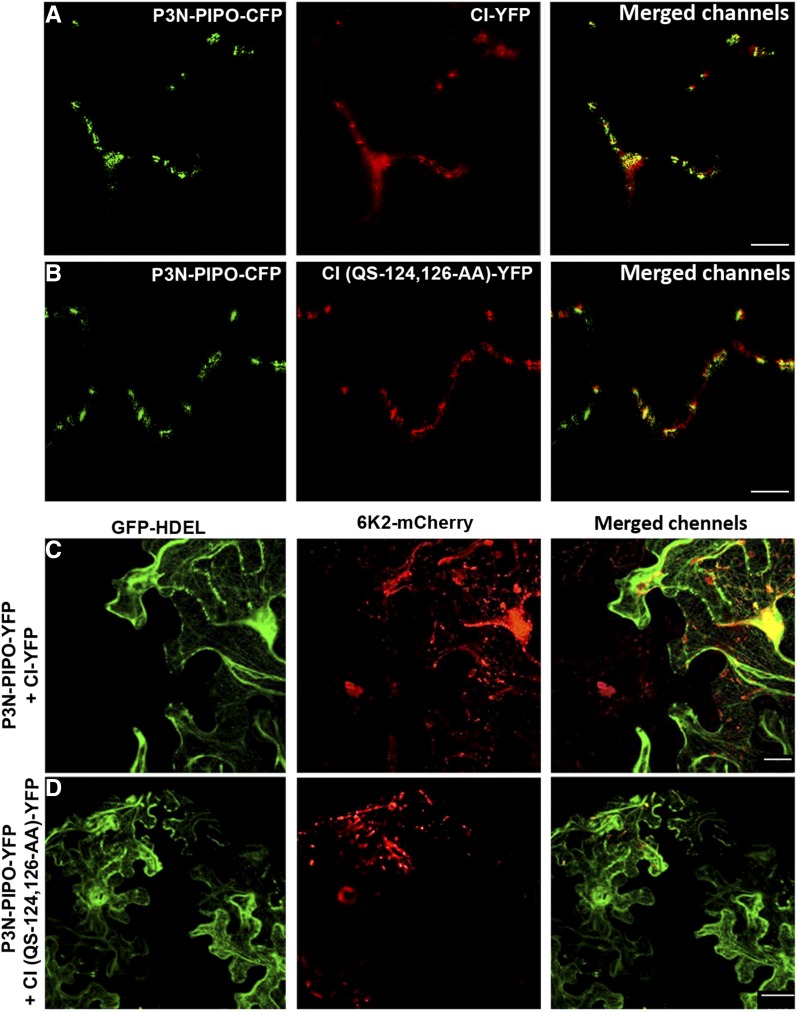

Interaction between CI and 6K2 Is Required for the Intercellular Movement of 6K2 Vesicles

In a previously reported screening, several mutants of the CI helicase from the potyvirus Tobacco etch virus that delayed virus intercellular movement were identified. One of the identified mutants, CI(RE-122,124-AA), presented severely delayed intercellular movement but showed no defect in the viral replication (Carrington et al., 1998). The corresponding mutation (QS-124,126-AA) was introduced in the CI-NubG fusion plasmid, and its interaction with PLV-Cub-6K2 was tested. CI(QS-124,126-AA)-NubG failed to interact with PLV-Cub-6K2 (Fig. 7A, row 5). The QS-124,126-AA mutation was then introduced in the fluorescently labeled CI-YFP protein to make CI(QS-124,126-AA)-YFP, and its localization was examined when coexpressed with P3N-PIPO-CFP. Interestingly, as CI-YFP (Fig. 8A), the mutated CI(QS-124,126-AA)-YFP still colocalized with P3N-PIPO-CFP (Fig. 8B). The localization of CI to PD is mediated by P3N-PIPO through the physical interaction between the two proteins (Wei et al., 2010b). By using fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), we revealed that, just like wild-type CI-YFP (Supplemental Fig. S1D), CI(QS-124,126-AA)-YFP could still interact with P3N-PIPO-CFP (Supplemental Fig. S1E).

Figure 8.

Although still localized on PD, mutated CI(QS-124,126-AA)-YFP does not support the intercellular movement of 6K2-mCherry. A and B, Colocalization of P3N-PIPO-CFP with CI-YFP (A) and CI(QS-124,126-AA)-YFP (B). Bars = 5 μm. C and D, Intercellular movement of 6K2-mCherry vesicles by coexpression of the dual construct pCambia/6K2-mCherry/GFP-HDEL with P3N-PIPO-YFP and either CI-YFP (C) or CI(QS-124,126-AA)-YFP (D). Bars = 10 μm.

We then tested if the CI(QS-124,126-AA) mutant together with P3N-PIPO can facilitate the intercellular movement of 6K2 vesicles. For this, the dual construct pCambia/6K2-mCherry/GFP-HDEL was coexpressed with P3N-PIPO-YFP and either CI-YFP or CI(QS-124,126-AA)-YFP, and the cell-to-cell movement of 6K2-mCherry was evaluated as described (Agbeci et al., 2013). 6K2-mCherry was only able to move intercellularly when coexpressed with P3N-PIPO-YFP and CI-YFP (Fig. 8C) but not with P3N-PIPO-YFP and CI(QS-124,126-AA)-YFP (Fig. 8D). This result indicates that the interaction between 6K2 and CI is important for the intercellular movement of 6K2.

The Subcellular Basis of the Roles of CI and P3N-PIPO in the Intercellular Movement of TuMV 6K2 Vesicles

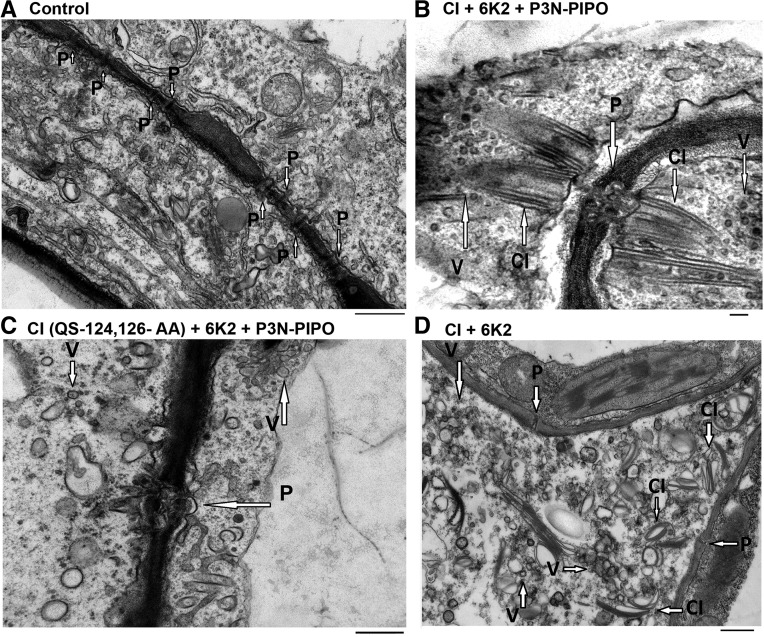

Since P3N-PIPO and CI form a minimal viral complex that supports the movement of 6K2 vesicles, and the interaction between 6K2 and CI is important for the intercellular movement of 6K2 vesicles, we next investigated the subcellular basis of how P3N-PIPO and CI could support the intercellular movement of 6K2 vesicles by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). In noninfected cells, simple, linear PDs (Fig. 9A, P and arrows) were seen and no vesicles and cylindrical inclusion bodies were revealed (Fig. 9A). TEM imaging of the ectopic coexpression of 6K2 with CI and P3N-PIPO in Nicotiana benthamiana leaf cells showed that there was a severe alteration in the PD structure, with the formation of branched or structurally modified PDs (Fig. 9B, P and arrows). Cylindrical inclusion bodies (Fig. 9B, CI and arrows) that linked a group of vesicular structures (Fig. 9B, V and arrows) and branched PDs also were seen (Fig. 9B). Interestingly, in N. benthamiana leaf cells with the ectopic coexpression of 6K2 with CI(QS-124,126-AA) and P3N-PIPO, although there was a formation of branched or structurally modified PDs (Fig. 9C, P and arrow), no cylindrical inclusion bodies were observed. Vesicular structures were seen away from PDs (Fig. 9C, V and arrows). On the other hand, in N. benthamiana leaf cells with the ectopic coexpression of 6K2 with CI but without P3N-PIPO, although cylindrical inclusion bodies (Fig. 9D, CI and arrows) and vesicular structures (Fig. 9D, V and arrows) were observed, they were not close to PDs but inside the cytoplasm instead (Fig. 9D). Moreover, consistent with the proposed role of P3N-PIPO in the modification of PD (Vijayapalani et al., 2012), no structural change of PDs was revealed in these cells (Fig. 9D, P and arrows). These TEM images indicated that, while P3N-PIPO is involved in the structural change of PDs, CI could serve as a connection between P3N-PIPO-modified PD and 6K2-tagged replication vesicles for the correct PD targeting and intercellular transport of 6K2-coated vesicles through PDs.

Figure 9.

Subcellular basis of the roles of CI and P3N-PIPO in the intercellular movement of TuMV 6K2 vesicles. TEM images show a cell from noninfected N. benthamiana leaf (A), a cell with ectopic coexpression of 6K2 with CI and P3N-PIPO in N. benthamiana leaf (B), a cell with ectopic coexpression of 6K2 with CI(QS-124,126-AA) and P3N-PIPO in N. benthamiana leaf (C), and a cell with ectopic coexpression of 6K2 with CI in N. benthamiana leaf (D). Arrow P shows plasmodesmata, arrow V shows 6K2-induced vesicles, and arrow CI shows the cylindrical inclusion bodies. Bars = 500 nm (A, C, and D) and 100 nm (B).

DISCUSSION

CI and P3N-PIPO Compose a Minimal Complex Where CI Serves as a Docking Point for the Intercellular Movement of 6K2 Vesicles

It is generally accepted that plant viruses move intercellularly through the modification of PDs. Most plant viruses encode for at least one protein that is dedicated to the intercellular movement of viral particles (Ueki and Citovsky, 2011). In the case of TuMV, there are at least three proteins involved in the cell-to-cell movement of the virus: P3N-PIPO, CI, and CP. Among these three viral proteins, P3N-PIPO, targeted to PDs, is known to be involved in the increase of the SEL of PDs (Vijayapalani et al., 2012). P3N-PIPO also is involved in the targeting of CI to PD through physical interaction between these two proteins (Wei et al., 2010a). It has been proposed that CI and P3N-PIPO form a complex that could facilitate the intercellular movement of potyviruses in infected plants (Wei et al., 2010a); however, it is not clear how this complex is involved in the intercellular movement of potyviruses.

TuMV 6K2-induced replication vesicles are capable of moving intercellularly through PDs during TuMV infection. However, when expressed ectopically, even though 6K2 can induce the formation of these vesicles, these 6K2 vesicles are incapable of moving from cell to cell (Grangeon et al., 2013). In this study, we found that the viral proteins P3N-PIPO and CI are necessary and sufficient for the targeting of 6K2 vesicles to PD and also are able to facilitate the intercellular movement of 6K2 vesicles during ectopic expression. Thus, we propose that CI and P3N-PIPO compose a minimal complex required for the intercellular movement of 6K2 vesicles. The transport of P3N-PIPO to PDs requires a classic secretory pathway (Wei et al., 2010b; this study), while the targeting of 6K2 to PD takes a different route other than the classic secretory pathway (this study). We found that disrupting the PD localization of P3N-PIPO through the expression of RabE1d(NI) impairs the PD targeting of the 6K2 vesicles. This indicates that P3N-PIPO is one of the key factors involved in the PD targeting of 6K2 vesicles. P3N-PIPO is capable of interacting with CI for the PD localization of CI (Wei et al., 2010a). We found that 6K2 is capable of interacting physically with the CI protein but not P3N-PIPO. We thus propose that, during the intercellular transport of 6K2 vesicles though PDs, CI could serve as a connection between P3N-PIPO and the 6K2-induced replication vesicles. This notion is further supported by the fact that the CI(QS-124,126-AA) mutant, which disrupts its interaction with 6K2, fails to support the intercellular movement of the 6K2 vesicles, although the mutated CI can still maintain its interaction with P3N-PIPO and be localized to the PDs. It is interesting that the mutated CI also fails to form cylindrical inclusions. However, we do not know whether this is because of failed CI interaction with 6K2 or that the amino acids mutated per se are required for the formation of cylindrical inclusions. P3N-PIPO, localized to the PD, is known to be able to modify the SEL of PDs (Vijayapalani et al., 2012). During infection, CI localizes to PD through its interaction with P3N-PIPO (Wei et al., 2010b). It is highly likely that 6K2 vesicles, once they are transported to the vicinity of PDs, are docked to PDs via its interaction with CI. Indeed, in our TEM analysis, cylindrical inclusion bodies that link a group of vesicular structures and structurally modified PDs are frequently seen in cells ectopically expressing P3N-PIPO, CI, and 6K2, but no such cylindrical inclusion bodies are seen in cells expressing P3N-PIPO, the CI(QS-124,126-AA) mutant, and 6K2, despite the structurally modified PDs and vesicular structures away from the modified PDs.

Based on the results discussed above, we propose the following model for the intercellular movement of TuMV 6K2 replication vesicles. In a TuMV-infected cell, upon successful replication, the P3N-PIPO protein is transported to PD, through classic ER-to-Golgi and post-Golgi transport pathways. The SEL of the PD is then increased by P3N-PIPO (Vijayapalani et al., 2012). CI presumably localizes to the modified PD through its interaction with P3N-PIPO (Wei et al., 2010b). The 6K2-formed replication vesicles traffic along the actomyosin system toward the cell periphery, eventually tether to PD by the interaction between the 6K2 on the replication vesicle and the inclusion bodies formed by CI bound to P3N-PIPO, then the vesicles are docked to the P3N-PIPO-modified PD. The PD-docked replication vesicles then go through the modified PD into the neighboring cell (Grangeon et al., 2013).

An Infection-Independent Intercellular 6K2 Vesicle Movement Assay

Previous studies on the regulation of the intercellular movement of potyviruses used infection assays (Carrington et al., 1998; Gómez de Cedrón et al., 2006; Wei et al., 2010b; Vijayapalani et al., 2012; Deng et al., 2015). These studies provide valuable information about the function of both viral and host factors involved in the intercellular movement of the viruses; however, the viral replication as well as intracellular and intercellular movement are linked during potyviral infection (Blanc et al., 1997; Carrington et al., 1998; Deng et al., 2015). This makes the precise identification of the mechanism of action of host and viral proteins in the intercellular spread of the virus difficult.

In this study, an infection-free intercellular 6K2 vesicle movement assay is developed. Since there is no replication, the only process being observed is the cell-to-cell spread of the 6K2 vesicles. When combined with the expression of the dual construct pCambia/6K2-mCherry/GFP-HDEL (Grangeon et al., 2013), this system can be used to quantify the intercellular movement of 6K2 vesicles by measuring the number of cells showing green and red fluorescence in comparison with the number of cells showing red fluorescence only. With this system, the efficiency of this process could be measured accurately under different experimental conditions. This also could prove to be a valuable tool in future studies about the precise mode of action of additional viral and host proteins involved in the intercellular spread of TuMV to form a more comprehensive model of the intracellular and intercellular movement of this virus. One of the proteins of interest to be studied further is CP. This protein is located to the PD together with P3N-PIPO and CI (Wei et al., 2010b), but its involvement in the cell-to-cell movement of replication vesicles is still not clear.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid Construction and Site-Directed Mutagenesis

The coding sequence of CI was amplified by PCR using the TuMV infectious clone (Cotton et al., 2009) as template and cloned into the pCR8 entry vector following the instructions from the manufacturer (ThermoFisher Scientific). P3N-PIPO results from the translation of an RNA template containing an A insertion in the conserved GA6 (from GGAAAAAA to GGAAAAAAA; Olspert et al., 2016). To mimic this, we inserted a G between A3 and A4 in the GA6 sequence (GGAAAAAA to GGAAAGAAA) by PCR (Chung et al., 2008). This insertion does not result in any changes in the amino acid sequence. The amplified P3N-PIPO was then cloned into the pCR8 entry vector following the instructions from the manufacturer (ThermoFisher Scientific).

The CI and P3N-PIPO genes cloned into pCR8 were cloned into pXN22-DEST (Grefen et al., 2007) using LR Clonase II plus enzyme mix (ThermoFisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions to obtain the CI-NubG and P3N-PIPO-NubG fusions. Construction of the PLV-Cub-6K2 plasmid was as described (Jiang et al., 2015). The construction of PLV-Cub-RHD3 and NubG-RHD3 was described by Chen et al. (2011). For the fluorescently labeled versions of CI and P3N-PIPO proteins, the CI and P3N-PIPO genes were cloned into the Gateway-compatible vector pEarleyGate102 (X-CFP) to obtain the fluorescent fusion proteins CI-CFP and P3N-PIPO-CFP. CI and P3N-PIPO were additionally cloned into pEarleyGate101 (X-YFP) (Earley et al., 2006) using LR Clonase II plus enzyme mix (ThermoFisher Scientific) to obtain CI-YFP and P3N-PIPO-YFP. The pCambia/6K2-mCherry and pCambia/6K2-CFP (Jiang et al., 2015), the dual pCambia/6K2-mCherry/GFP-HDEL (Grangeon et al., 2013), and the PD markers PDLP1-GFP (Amari et al., 2010, 2011) were provided by Jean-François Laliberté. The point mutations of CI were generated with the QuikChange Lightning kit (Agilent) using the pEarleyGate101/CI-YFP and pXN22/CI-NubG plasmids as template to obtain the CI(QS-124,126-AA)-YFP and CI(QS-124,126-AA)-NubG protein fusions, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The pVKHEn6-RabE1d and pVKHEn6-RabE1d(NI) plasmids were used for the expression of these proteins. The construction of these plasmids was described by Zheng et al. (2005).

Transient Protein Expression in Nicotiana benthamiana

The pCambia/6K2-mCherry, pCambia/6K2-mCherry/GFP-HDEL, pVKH-RabE1d, and pVKH-RabE1d(NI) plasmids were provided in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. The P3N-PIPO-YFP, P3N-PIPO-CFP, CI-YFP, and CI-CFP plasmids were transformed into A. tumefaciens by using a modified freeze-thaw procedure (Höfgen and Willmitzer, 1988). A. tumefaciens containing the corresponding plasmids was grown in Luria-Bertani broth supplemented with kanamycin alone [for pCambia/6K2-mCherry, pCambia/6K2-mCherry/GFP-HDEL, pVKH-RabE1d, and pVKH-RabE1d(NI)] or kanamycin, gentamycin, and rifampicin overnight at 28°C with shaking. The cells were centrifuged at 2,000g for 10 min and resuspended in infiltration buffer (10 mm MgCl2 and 150 μm acetosyringone). The cell suspension was incubated for 4 h at room temperature before infiltration. The OD600 was adjusted to 0.05 for the RabE1d- and RabE1d(NI)-containing strains and to 0.1 for the rest. The agroinfiltration was done in 4-week-old N. benthamiana plants as described previously (Sparkes et al., 2006).

Confocal Microscopy

Agroinfiltrated leaf sections were imaged using a Leica SP8 and/or Leica D6000 with a 40× immersion objective at 3 dpi. Lasers of 448, 488, and 561 nm were used to excite CFP, GFP, and mCherry, respectively. The capture was done at 460 to 480, 500 to 540, and 580 to 620 nm for CFP, GFP, and mCherry, respectively. Image processing was done in ImageJ (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/). The Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the fluorescent signals was measured using the JACoP plug-in (Bolte and Cordelières, 2006) in ImageJ. To determine the abundance and size of the small vesicles, a stack was taken of individual cells expressing 6K2-mCherry, then the vesicles were counted using the 3D Object Counter plug-in in ImageJ using a size window of 10 to 1,000 voxels. To measure the average speed of the 6K2 vesicles, a time-lapse film was taken and the speed was measured with the MTrackJ plug-in (Meijering et al., 2012) in ImageJ.

Y2H-SUS Assay

The Y2H-SUS experiments were carried out as described by Grefen et al. (2007). The THY-AP4 (MATa ura3 leu2 lexA: lacZ: trp1 lexA: HIS3 lexA:ADE2) strain containing PLV-Cub-6K2 was used. CI-NubG and its mutant version CI(QS-124,126-AA)-NubG were transformed into the THY-AP5 (MAT55 URA3 leu2 trp1 his3 loxP: ade2) yeast strain. The transformation of the yeast strains was performed using a lithium acetate-based protocol (Grefen et al., 2007). Following transformation, the THY-AP4 and THY-AP5 strains were mated and plated on SC-Leu-Trp plates (Grefen et al., 2007). Mated cells were then plated on SC-Leu-Trp-His plates supplemented with X-Gal and 1 mm of the HIS3 competitive inhibitor 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (Brennan and Struhl, 1980).

BiFC Analysis

For BiFC analysis, YFPn-6K2, YFPc-CI, and P3N-PIPO-YFPc were made by fusion of either residues 1 to 174 of YFP (termed YFPn) or residues 175 to 239 (termed YFPc) with 6K2 and CI or P3N-PIPO in the corresponding Gateway destination vectors pMDC32-YFPn-C, pMDC32-YFPc-C, and pMDC32-N-YFPc. These Gateway-compatible destination vectors were created by inserting HindIII-SstI fragments of pUGW2-nEYFP, pUGW2-cEYFP, and pUGW0-cEYFP (Nakagawa et al., 2007) into the same cutting site of the binary vector pMDC32 (Curtis and Grossniklaus, 2003). The YFPn-6K2, YFPc-CI, and P3N-PIPO-YFPc plasmids were then transformed into A. tumefaciens by using a modified freeze-thaw procedure (Höfgen and Willmitzer, 1988). YFPn-6K2 was then coexpressed with unfused YFPc, or YFPc-CI or P3N-PIPO-YFPc, and unfused YFPn with P3N-PIPO-YFPc with A. tumefaciens-mediated transient expression (Sparkes et al., 2006) at OD600 = 0.03 in N. benthamiana leaf lower epidermal cells. The fluorescence of YFP was then assessed 96 h postinfiltration using a Leica SP8 microscope with a 40× immersion objective. Lasers of 488 nm were used to excite YFP, and the emission was captured at 510 to 560 nm.

Western-Blot Analyses

The leaves of 6-week-old N. benthamiana plants agroinfiltrated with either YFPn-6K2 and P3N-PIPO-YFPc or YFPn-6K2 and YFPc-CI for BiFC analysis were ground in liquid nitrogen, and 1 g of the powder was mixed with 1 mL of SDS-PAGE loading buffer in 1.5-mL tubes. The proteins were extracted by boiling the mixture for 10 min at 100°C. After centrifugation for 1 min at 13,000 rpm, the supernatant was used for western blotting. Proteins were loaded on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel. SDS-PAGE was performed on a Protean III apparatus (Bio-Rad), and separated proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Immunoblotting was carried out once with anti-EYFPn rabbit serum as the primary antibody at a 1:10,000 dilution and, the other time, with anti-EYFPc rabbit serum at a 1:5,000 dilution. The secondary antibody was anti-rabbit IgG-peroxidase (Sigma-Aldrich) at a 1:5,000 dilution. Signals were detected using Invitrogen Novex ECL (HRP Chemiluminescent Substrate Reagent Kit) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The protein loading was verified by Coomassie Blue staining.

TEM

Small pieces (1.5 mm × 2 mm) of mock- or agro-infiltrated leaf (5 dpi) or upper TuMV systemically infected leaf were cut and fixed in 2.5% (w/v) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 m sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4, for 24 h at 4°C. After rinsing three times for 10 min each in washing buffer at room temperature, the samples were postfixed in 1% (w/v) osmium tetroxide with 1.5% (w/v) potassium ferrocyanide in sodium cacodylate buffer for 2 h at 4°C. The samples were then rinsed in washing buffer at room temperature (three times for 15 min each) and stained with 1% (w/v) tannic acid for 1 h at 4°C. After rinsing in water (three times for 10 min each) at room temperature, the samples were dehydrated in a graded acetone series (30%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 100%) for 20 min at each step at room temperature. The 100% acetone rinse was repeated two more times. The samples were then gradually infiltrated with increasing concentrations of Epon 812 resin (50%, 66%, 75%, and 100%) mixed with acetone for a minimum of 8 h for each step. A 25-p.s.i. vacuum was applied, when the samples were in pure Epon 812 resin. Samples were finally embedded in pure, fresh Epon 812 resin and polymerized at 60°C for 48 h. After polymerization, the 100-nm ultrathin sections were obtained and stained with 4% (w/v) uranyl acetate for 8 min and Reynolds lead citrate for 5 min. Then, the sections were examined in a Tecnai T12 transmission electron microscope (FEI) operating at 120 kV. Images were recorded using an AMT XR80C CCD camera system (FEI).

FRET Microscopy

For FRET microscopy analysis, a spectral imaging method was performed. Agroinfiltrated N. benthamiana leaf sections expressing CFP and YFP alone, coexpression of 6K2-CFP and P3N-PIPO-YFP, coexpression of CI-CFP and P3N-PIPO-YFP, and coexpression of CI(QS-124,126-AA)-CFP and P3N-PIPO-YFP were imaged at 5 dpi using a Zeiss LSM780 Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope with spectral detector and a 63×/1.4 immersion Oil DICIII Plan Apochromat objective. The excitation was from a 405-nm/30-mW laser. The spectrum was measured from 455 to 560 nm in 10-nm increments. The CFP and YFP (a result of FRET from CFP and YFP) signal was separated from the FRET image through the spectral unmixing process. Image processing was done in ImageJ (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/).

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. The mutated CI(QS-124,126-AA) still interacts with P3N-PIPO.

Acknowledgments

We thank the research group of the Facility for Electron Microscopy Research at McGill University, where we conducted all the TEM experiments.

Footnotes

This research was supported by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and from Fonds Québec de la Recherche sur la Nature et les Technologies (FRQNT) to J.-F.L. and H.Z.

References

- Agbeci M, Grangeon R, Nelson RS, Zheng H, Laliberté JF (2013) Contribution of host intracellular transport machineries to intercellular movement of turnip mosaic virus. PLoS Pathog 9: e1003683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amari K, Boutant E, Hofmann C, Schmitt-Keichinger C, Fernandez-Calvino L, Didier P, Lerich A, Mutterer J, Thomas CL, Heinlein M, et al. (2010) A family of plasmodesmal proteins with receptor-like properties for plant viral movement proteins. PLoS Pathog 6: e1001119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amari K, Lerich A, Schmitt-Keichinger C, Dolja VV, Ritzenthaler C (2011) Tubule-guided cell-to-cell movement of a plant virus requires class XI myosin motors. PLoS Pathog 7: e1002327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchemin C, Boutet N, Laliberté JF (2007) Visualization of the interaction between the precursors of VPg, the viral protein linked to the genome of turnip mosaic virus, and the translation eukaryotic initiation factor iso 4E in planta. J Virol 81: 775–782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchemin C, Laliberté JF (2007) The poly(A) binding protein is internalized in virus-induced vesicles or redistributed to the nucleolus during turnip mosaic virus infection. J Virol 81: 10905–10913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benitez-Alfonso Y, Faulkner C, Ritzenthaler C, Maule AJ (2010) Plasmodesmata: gateways to local and systemic virus infection. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 23: 1403–1412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc S, López-Moya JJ, Wang R, García-Lampasona S, Thornbury DW, Pirone TP (1997) A specific interaction between coat protein and helper component correlates with aphid transmission of a potyvirus. Virology 231: 141–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolte S, Cordelières FP (2006) A guided tour into subcellular colocalization analysis in light microscopy. J Microsc 224: 213–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburg B, Zhuang X (2007) Virus trafficking: learning from single-virus tracking. Nat Rev Microbiol 5: 197–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breeze E, Dzimitrowicz N, Kriechbaumer V, Brooks R, Botchway SW, Brady JP, Hawes C, Dixon AM, Schnell JR, Fricker MD, et al. (2016) A C-terminal amphipathic helix is necessary for the in vivo tubule-shaping function of a plant reticulon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: 10902–10907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan MB, Struhl K (1980) Mechanisms of increasing expression of a yeast gene in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol 136: 333–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington JC, Jensen PE, Schaad MC (1998) Genetic evidence for an essential role for potyvirus CI protein in cell-to-cell movement. Plant J 14: 393–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Stefano G, Brandizzi F, Zheng H (2011) Arabidopsis RHD3 mediates the generation of the tubular ER network and is required for Golgi distribution and motility in plant cells. J Cell Sci 124: 2241–2252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung BY, Miller WA, Atkins JF, Firth AE (2008) An overlapping essential gene in the Potyviridae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 5897–5902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton S, Grangeon R, Thivierge K, Mathieu I, Ide C, Wei T, Wang A, Laliberté JF (2009) Turnip mosaic virus RNA replication complex vesicles are mobile, align with microfilaments, and are each derived from a single viral genome. J Virol 83: 10460–10471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MD, Grossniklaus U (2003) A Gateway cloning vector set for high-throughput functional analysis of genes in planta. Plant Physiol 133: 462–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng P, Wu Z, Wang A (2015) The multifunctional protein CI of potyviruses plays interlinked and distinct roles in viral genome replication and intercellular movement. Virol J 12: 141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufresne PJ, Thivierge K, Cotton S, Beauchemin C, Ide C, Ubalijoro E, Laliberté JF, Fortin MG (2008) Heat shock 70 protein interaction with Turnip mosaic virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase within virus-induced membrane vesicles. Virology 374: 217–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earley KW, Haag JR, Pontes O, Opper K, Juehne T, Song K, Pikaard CS (2006) Gateway-compatible vectors for plant functional genomics and proteomics. Plant J 45: 616–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez de Cedrón M, Osaba L, López L, García JA (2006) Genetic analysis of the function of the plum pox virus CI RNA helicase in virus movement. Virus Res 116: 136–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grangeon R, Agbeci M, Chen J, Grondin G, Zheng H, Laliberté JF (2012) Impact on the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus of turnip mosaic virus infection. J Virol 86: 9255–9265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grangeon R, Jiang J, Wan J, Agbeci M, Zheng H, Laliberté JF (2013) 6K2-induced vesicles can move cell to cell during turnip mosaic virus infection. Front Microbiol 4: 351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grefen C, Lalonde S, Obrdlik P (2007) Split-ubiquitin system for identifying protein-protein interactions in membrane and full-length proteins. Curr Protoc Neurosci 5: 5.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höfgen R, Willmitzer L (1988) Storage of competent cells for Agrobacterium transformation. Nucleic Acids Res 16: 9877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Patarroyo C, Garcia Cabanillas D, Zheng H, Laliberté JF (2015) The vesicle-forming 6K2 protein of Turnip Mosaic Virus interacts with the COPII coatomer Sec24a for viral systemic infection. J Virol 89: 6695–6710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijering E, Dzyubachyk O, Smal I (2012) Methods for cell and particle tracking. Methods Enzymol 504: 183–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Suzuki T, Murata S, Nakamura S, Hino T, Maeo K, Tabata R, Kawai T, Tanaka K, Niwa Y, et al. (2007) Improved Gateway binary vectors: high-performance vectors for creation of fusion constructs in transgenic analysis of plants. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 71: 2095–2100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas O, Laliberté JF (1992) The complete nucleotide sequence of turnip mosaic potyvirus RNA. J Gen Virol 73: 2785–2793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niehl A, Heinlein M (2011) Cellular pathways for viral transport through plasmodesmata. Protoplasma 248: 75–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olspert A, Carr JP, Firth AE (2016) Mutational analysis of the Potyviridae transcriptional slippage site utilized for expression of the P3N-PIPO and P1N-PISPO proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 44: 7618–7629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritzenthaler C. (2011) Parallels and distinctions in the direct cell-to-cell spread of the plant and animal viruses. Curr Opin Virol 1: 403–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparkes IA, Runions J, Kearns A, Hawes C (2006) Rapid, transient expression of fluorescent fusion proteins in tobacco plants and generation of stably transformed plants. Nat Protoc 1: 2019–2025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speth EB, Imboden L, Hauck P, He SY (2009) Subcellular localization and functional analysis of the Arabidopsis GTPase RabE. Plant Physiol 149: 1824–1837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueki S, Citovsky V (2011) To gate, or not to gate: regulatory mechanisms for intercellular protein transport and virus movement in plants. Mol Plant 4: 782–793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayapalani P, Maeshima M, Nagasaki-Takekuchi N, Miller WA (2012) Interaction of the trans-frame potyvirus protein P3N-PIPO with host protein PCaP1 facilitates potyvirus movement. PLoS Pathog 8: e1002639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan J, Basu K, Mui J, Vali H, Zheng H, Laliberté JF (2015) Ultrastructural characterization of Turnip mosaic virus-induced cellular rearrangements reveals membrane-bound viral particles accumulating in vacuoles. J Virol 89: 12441–12456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei T, Huang TS, McNeil J, Laliberté JF, Hong J, Nelson RS, Wang A (2010a) Sequential recruitment of the endoplasmic reticulum and chloroplasts for plant potyvirus replication. J Virol 84: 799–809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei T, Zhang C, Hong J, Xiong R, Kasschau KD, Zhou X, Carrington JC, Wang A (2010b) Formation of complexes at plasmodesmata for potyvirus intercellular movement is mediated by the viral protein P3N-PIPO. PLoS Pathog 6: e1000962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H, Camacho L, Wee E, Batoko H, Legen J, Leaver CJ, Malhó R, Hussey PJ, Moore I (2005) A Rab-E GTPase mutant acts downstream of the Rab-D subclass in biosynthetic membrane traffic to the plasma membrane in tobacco leaf epidermis. Plant Cell 17: 2020–2036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]