Abstract

Background:

Local natural medicinal resource knowledge is important to define and elaborate usage of herbs, in systematic and organized manner. Until recently, there has been little scientifically written document regarding the traditional uses of medicinal plants in Al Bahah region.

Objective:

This pilot study aims to collect the ethnobotanical information from native populations regarding the benefits of medicinal plants of Al Bahah region, and determine if the traditional usage is scientifically established (proved) from literature.

Materials and Methods:

The survey collected data for 39 plant species recorded by informants for their medicinal benefits. The recorded species were distributed among 28 plant families. Leguminosae and Euphorbiaceae were represented each by 3 species, followed by Asteraceae (2 species), Lamiaceae (2 species), Apocynaceae (2 species), and Solanaceae (2 species). All the medicinal plants were reported in their local names. Analysis of ethnopharmacological data was done to obtain percentage of plant families, species, parts of plants used, mode of administration, and preparation types.

Results:

Total 43 informants were interviewed, maximum number of species were used to cure skin diseases including burns (3), wounds (7), warts (1), Leishmania (7), topical hemostatic (2), followed by gastrointestinal system, rheumatism, respiratory tract problems, diabetes mellitus, anti-snake venom, malaria, and eye inflammation.

Conclusions:

The study covered Al Bahah city and its outskirts. Ten new ethnobotanical uses were recorded such as antirheumatic and anti-vitiligo uses for Clematis hirsute, leishmaniasis use of Commiphora gileadensis, antigout of Juniperus procera, removing warts for Ficus palmata.

SUMMARY

39 plant species from 28 plant families are used for treating more than 20 types of diseases.

Maximum number of species (23 species) was used for treating skin diseases (42.6%) including leishmaniasis, wound healing, dermatitis, psoriasis, vitiligo and warts.

Ten ethnobotanical uses of 8 studied plants have not been previously reported.

The most used medicinal plants, according to their Use Index (UI) were Juniperus procera, Rumex nervosus, and Ziziphus spina-christi.

Abbreviations Used: UI : Use Index, GI: Gastrointestinal tract, RD: Rheumatic disease, CVS: Cardiovascular diseases, UTI: Urinary tract infection, DM: Diabetes mellitus, RT: Respiratory infection, KSA: Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Key words: Al Bahah, ethnopharmacology, folk medicine, medicinal plants, Saudi Arabia, survey

INTRODUCTION

Not <400,000 flowering plants are found on the earth.[1] About 12% of them are used in the traditional medicine.[2,3,4] About 10,000 of those plants have already been scientifically investigated and described. In Western medicine system, higher plant-derived substances constitute around 25% of prescribed medicines and 74% of the 121 bioactive plant-derived compounds were identified through research based on leads from traditional medicine.[5] The knowledge of medicinal plant uses was acquired by means of trial and error and transmitted from the older to the younger people, but this knowledge and transmission are in danger because transmission between older and younger generation is not always assured.[6,7]

Indigenous knowledge of Saudi traditional medicine ancient and still available among the tribal and local people and medicinal healers (Hakim). In KSA, more than 1200 (over 50%) of the total flowering plants (2250) are expected to be of medicinal importance.[8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15] This indigenous knowledge and traditional experiences have been passed verbally devoid of documentation and the traditional healers are dying without passing their knowledge. Besides, the urbanization of the indigenous customs results in more and more loss of the old knowledge of this human heritage. Therefore, there is an urgent necessity for documenting those vast stores of knowledge through ethnobotanical surveys, before their disappearance from the community, especially in Al Bahah. Al Bahah region is located in the Southwest of Saudi Arabia, enjoying with different geographical regions - mountainous, plains, coastal, and high biodiversity. Until recently, there has been little scientifically written documentation regarding the traditional uses of medicinal plants in Al Bahah region.[16,17] Therefore, we focused on our project on collecting and documenting the ethnobotanical knowledge in Al Bahah region.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

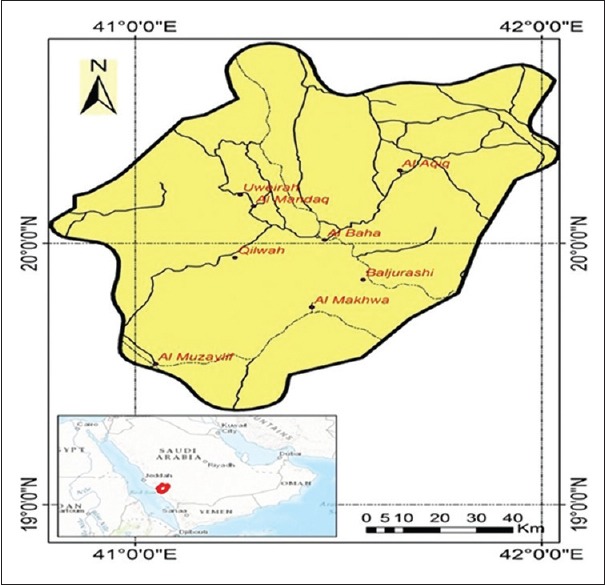

Al Bahah region is located in the Southwest of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia between Makkah region and Aseer region [Figure 1]. The city is located in an area surrounded by natural tree and agricultural plateaus. The province is famous for beautiful forests, wildlife areas, valleys, and mountains. The area contains more than 53 well-known forests dominated by Juniperus procera, among them are Raghdan, Ghomsan, Fayk, Skaran, and Aljabal. Al Bahah region is divided geographically into three different parts: High mountainous Sarah region with temperate weather and rich plant diversity due to relatively high annual rainfall, Eastern Tehama lowland coastal area with very hot and humid weather and very little average rainfall and the Eastern hills with cool winters, hot summers, and sparse vegetation cover. Main cities of Al Bahah region are Baljurashi, Almandaq, Qilwah, and Al-Mikhwah. The main two tribes of this region are Ghamid and Zahran. Al Bahah city experiences mild climate with temperatures ranging between 12°C and 23°C (53.6°F–73.4°F). Due to its location at 2500 m (8200 ft), the climate is moderate in summer and cold in winter above sea level. Humidity ranges from 52% to 67%. The mountainous region, As-Sarah, the weather is cooler in summer and winter. Annual rainfall in the mountainous region ranges between 229 and 581 mm. The average rainfall of the Al Bahah region ranges between 100 and 250 mm.

Figure 1.

Map of Al Bahah region

Data collection

Information on medicinal plants was collected from Al Bahah and surrounding regions such as Baljurashi, Al Mandaq, and Miqwah from October 2015 to June 2016. Ethnomedicinal information was collected by ethnobotanical interviews with informants (43) (local users 18, knowledgeable persons in herbal shops (10), and traditional healers (15); ethnomedicinal properties (local name, parts of plants, ailments, the way of preparation, and administration) of plants were reported through informal, interviews, plants collected were taxonomically identified. Voucher specimens are preserved at the Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Clinical Pharmacy, Al Baha University.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistical methods were applied to analyze and summarize the ethnomedicinal data such as percentage of families, species, administration types, preparation modes, and plant parts used.

RESULTS

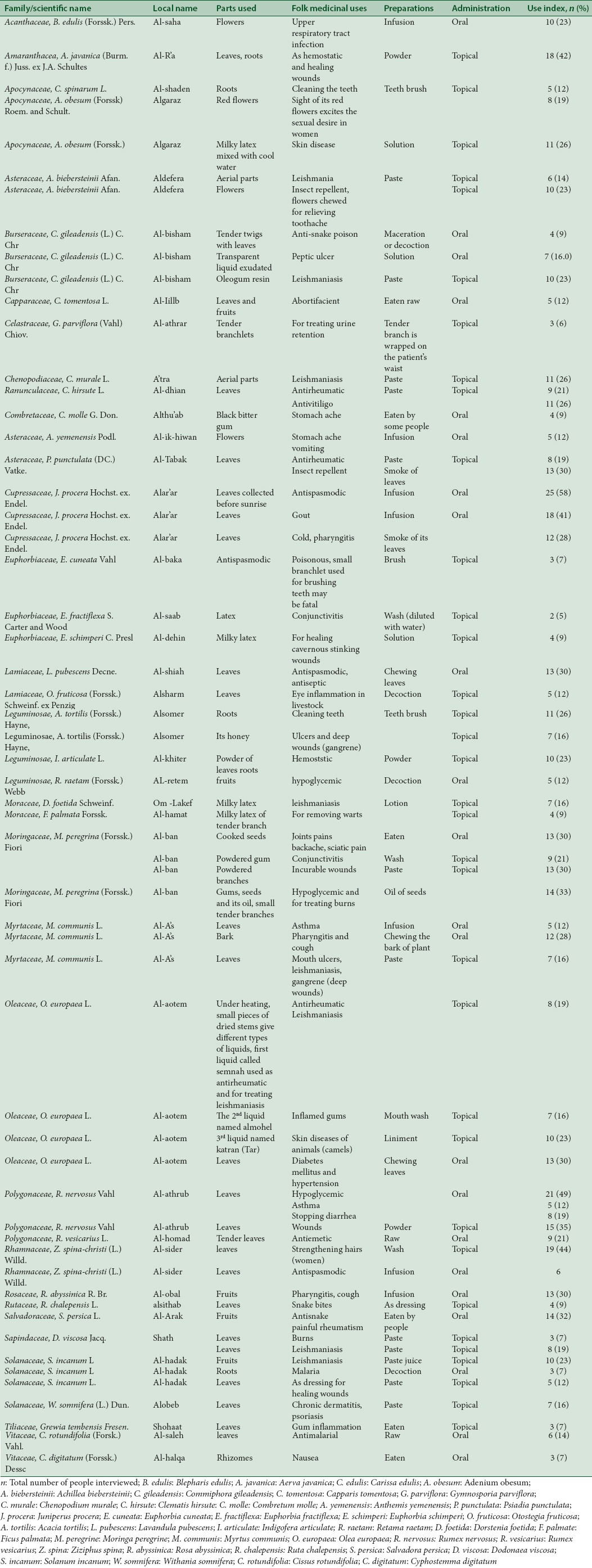

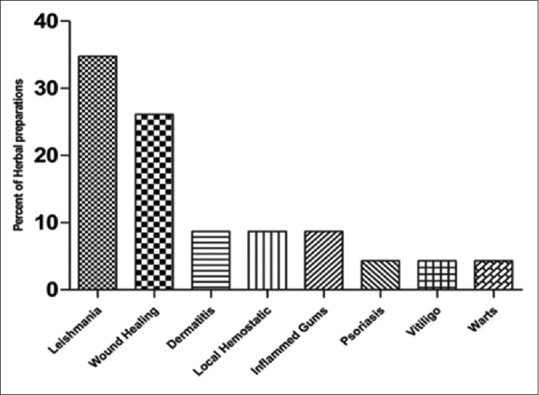

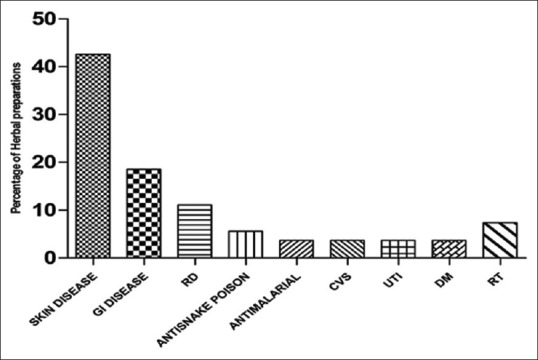

The survey collected ethnomedicinal information of 39 plant species recorded by informants for their medicinal benefits. The recorded species were distributed among 28 plant families. Leguminosae and Euphorbiaceae were represented each by 3 species, followed by Asteraceae (2 species), Lamiaceae (2 species), Apocynaceae (2 species, and Solanaceae (2 species). All the medicinal plants were reported in their local names listed in Table 1, and used in more than 20 types of diseases. Maximum number of species was used to cure skin diseases (23 species; 42.6%) including leishmaniasis (8; 34.8%), wound healing (6; 26.1%), dermatitis (2; 8.7%), local hemostatic (2; 8.7%), inflamed gums (2; 8.7%), psoriasis (1; 4.3%), vitiligo (1; 4.3%), warts (1; 4.3%) [Figure 2] followed by the gastrointestinal system (10; 18.5%), rheumatism (6; 11.1%), anti-snake venom (3; 5.6%), antimalaria (2; 3.7%), cardiovascular diseases (2; 3.7%), urinary tract infection (2; 3.7%), diabetes mellitus (2; 3.7%),) and respiratory tract problems (4; 7.4%) [Figure 3].

Table 1.

Ethnobotanical plant species used as medicines in Albaha region

Figure 2.

Percent of herbal preparations used to cure skin diseases

Figure 3.

Percent of herbal preparations to cure human diseases; GI: Gastrointestinal tract; RD: Rheumatic disease; CVS: Cardiovascular diseases; UTI: Urinary tract infection; DM: Diabetes mellitus; RT: Respiratory infection

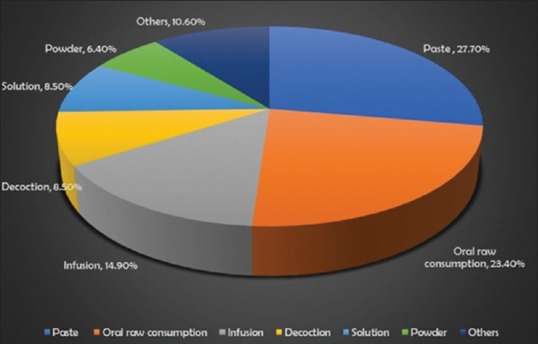

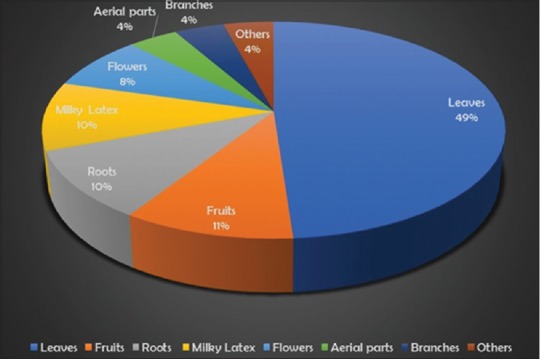

The principal modes of preparation were paste (27.7%), oral raw consumption (23.4%), infusion (14.9%), decoction (8.5%), powder (6.4%), solutions (8.5%), and others (10.6%) [Figure 4]. Most preparations were drawn from a single plant, often plant parts (fresh or dried) were ingested orally. Some preparations of plant parts were mixed with honey, water, and milk to improve the palatability of remedies. Among various plant parts used (leaves, fruits, branch lets, roots, rhizomes, flowers, fruits, seeds, and latex), the most frequently used plant part was the leaf, constituting 49 % followed by fruit (11 %), roots (10 %), milky latex (10%), flowers (8 %), aerial parts (4 %), branches (4 %) and others (4 %) [Figure 5]. Twenty-three plant preparations obtained from 18 plants of the total reported medicinal plants are used externally or taken as a gargle), followed by 12 species which are taken orally and 8 other species which are used both externally and internally application. By comparing the literature review in the ethnobotanical studies in Saudi Arabia and neighboring countries (Arabian Peninsula) with the current study, it was observed that ten ethnobotanical uses of 8 studied plants have not been previously recorded [Table 2]. A use index (UI%) was calculated to determine the importance of the use of each medicinal plant. The used index formula is UI = (na/NA ×100), where na is the number of interviewers who cite the species as useful and NA is the total number of people interviewed.

Figure 4.

Percent of modes of herbal preparation

Figure 5.

Percent of plant parts used for herbal remedies

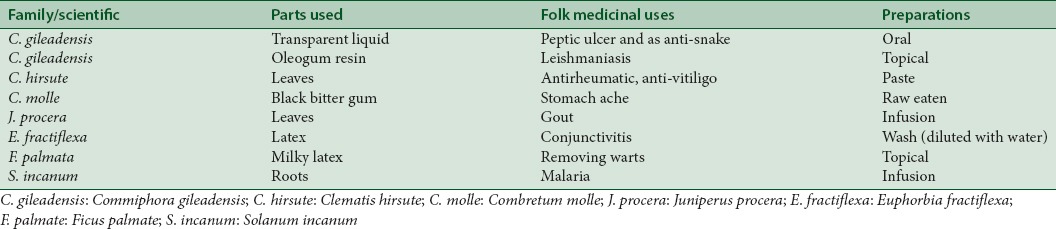

Table 2.

Plant species with new ethnopharmacological uses

DISCUSSION

Traditional herbal medicine has played a significant role currently as a topic for scientific research, particularly when the literature and field work data have been properly assessed. Such evaluation findings can offer several plants that can have the priority to be studied for specific biological activity based on the traditional herbal uses.[18] Ethnomedical uses of the plants can be utilized as an indicator for isolating bioactive compounds using bioactivity-guided fractionation method. This ethnomedicinal route provides positive activity in the order of 2–5 new compounds per 10,000 studied plants in comparison to the random route that gives positive activity in the order of one compound per 10,000 studied plants.[19,20,21] In this study, ethnomedicinal information was collected from 39 medicinal plants belonging to 28 plant families. There is no dominance of any plant family with a higher number of plant species. However, plant families with herbs are represented by Leguminosae, Asteraceae, Lamiaceae, Solanaceae. Their use may be preferred because of their ready availability.

The most used medicinal plants, according to their UI [Table 1], were J. procera, Rumex nervosus, and Ziziphus spina-christi. Those three medicinal plants are widespread species in Al Bahah and available during the whole year. Different parts of the plants were used for preparing the herbal remedies. However, in the majority of the plants, the herbal preparations were obtained from the leaves (45%) and similar observation has been recorded for other forested communities with green vegetation and abundant leaves.[22] It is known that leaves form a key part of plant identification and are the most easily available part to collect by local people.[23]

In addition, the preference toward leaves may be because leaves are the main photosynthetic organ in plants and are responsible mainly for the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites that acts on the body as bioactive compounds.[24] Hence, leaves are the source for photosynthates or exudates[25] that are toxins against environmental hazards and this character provides medicinal value to the human body. Most herbalists give remedies for skin diseases and sometimes for rheumatism in the form of washes and pastes, and for gastrointestinal diseases orally in the form of infusion, decoction, and oral raw consumption. Skin diseases were the most treated ailments by about 43% of herbal preparations mainly pastes and Leishmania and wound healing constitute the main skin diseases treated by 8 and 6 herbal preparations successively. At present, leishmaniasis is common in the human population in different localities, including the Eastern and Southern Province of Saudi Arabia and in particular endemic in the Al-Hassa Oasis.[26] While the antileishmanial activity of Myrtus communis, Achillea biebersteinii, Olea europaea, and Dodonaea viscosa was proved,[27,28,29,30,31] further antileishmanial screening should be done in the future for the following plants Commiphora gileadensis and Dorstenia foetida.

Rheumatic diseases, in particular, rheumatic arthritis, affectalmost 1%–2% of the population globally and attack women thrice as commonly as men. The spectrum of rheumatic diseases seen in Saudi Arabia appeared to be broadly similar to that seen in the West. In KSA, the rheumatic diseases affect 19.28/100,000 inhabitants.[32] However, most of the Saudi patients tends to use the conventional medicines for managing such disease, some of them still use the medicinal plants, especially in rural areas and among the old people. In our study, six plants were reported to manage rheumatic diseases, Clematis hirsute, Psiadia punctulata, Moringa peregrine, O. europaea, Withania somnifera, and J. procera. The anti-inflammatory activity of P. punctulata, M. peregrine, O. europaea, Salvadora persica, and W. somnifera was reported, and therefore, their traditional uses in folk medicine are justified scientifically.[33,34,35,36,37,38] C. hirsute and J. procera should be tested for cyclo- and lipo-xygenase inhibitory activity and related bioassays to verify their uses in traditional medicine as anti-inflammatory agents. Reports were found to the hypoglycemic effect of O. europaea leaves, Retama raetam fruits and M. peregrine,[39,40,41] but there has been no report about the hypoglycemic of R. nervosus that has been used traditionally as hypoglycemic agent.

When the present study is compared to ethnobotanical contributions done in KSA and neighboring countries, our findings disclosed that ten ethnobotanical uses of eight medicinal plants have been recorded for the first time [Table 2].[7,8,10,12,15,42,43,44,45,46] Little or no reports have been found so far regarding the bioactivity-guided fractionation of C. hirsute, J. procera, C. gileadensis, and D. foetida; therefore, those plants can be a target for further bioactivity-guided isolation. Ethnobotanical use in particular of C. hirsute for managing vitiligo should be proved using melanocytes bioassay, vitiligo, a disease that affects about 0.5%–1% of the world's population that means about 60 million suffering from this disease. The average age of onset is in the mid-twenties, but it can appear at any age. The disorder affects both sexes and all races equally; however, it is more noticeable in people with dark skin. Moreover, traditional antigout use of J. procera should be proved pharmacologically and the plant can be utilized economically for managing gout because the plant occurs as forests. It was reported that hyperuricemia is present in a considerable proportion of the Saudi people.[47] Most of the plants used for treating wound healing showed antimicrobial activity.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, this survey demonstrates that the culture of folk medicine is still practiced but on limited scale by the population in Al Bahah region. Pharmacological, toxicological, and phytochemical studies should be done for the promising medicinal plants mentioned in this research project, to assure their biological activity as well as their toxicity and then design therapeutic strategies based on the most effective and least toxic products in particular for J. procera and R. nervosus. J. procera can be utilized economically for medical purposes because it grows wild in vast areas in Al Bahah region.

Financial support and sponsorship

Funding for project number 55/1436 by Deanship of Higher Studies and Scientific Research, Albaha University, KSA.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Higher Studies and Scientific Research, Albaha University for funding this work through the project number 55/1436. The authors gratefully acknowledge this financial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Govaerts R. How many species of seed plant are there? Taxon. 2001;50:1085–90. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schippmann U, Cunningham AB, Leaman DJ. Biodiversity and the Ecosystem Approach in Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Ninth Regular Session of the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. Rome, Italy: FAO; 2002. Impact of cultivation and gathering of medicinal plants on biodiversity: Global trends and issues; pp. 143–67. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mondal S, Ghosh D, Ramakrishna K. A complete profile on blind-your-eye Mangrove Excoecaria agallocha L. (Euphorbiaceae): Ethnobotany, phytochemistry, and pharmacological aspects. Pharmacogn Rev. 2016;10:123–38. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.194049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoekou YP, Tchacondo T, Karou SD, Koudouvo K, Atakpama W, Pissang P, et al. Ethnobotanical study of latex plants in the maritime region of Togo. Pharmacognosy Res. 2016;8:128–34. doi: 10.4103/0974-8490.175613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rao MR, Palada MC, Becker BN. Medicinal and aromatic plants in agroforestry systems. Agroforestry Syst. 2004;61:107–22. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anyinam C. Ecology and ethnomedicine: Exploring links between current environmental crisis and indigenous medical practices. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:321–9. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)e0098-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vieira A. A comparison of traditional anti-inflammation and anti-infection medicinal plants with current evidence from biomedical research: Results from a regional study. Pharmacognosy Res. 2010;2:293–5. doi: 10.4103/0974-8490.72326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdel-Sattar E, Abou-Hussein D, Petereit F. Chemical constituents from the leaves of Euphorbia ammak growing in Saudi Arabia. Pharmacognosy Res. 2015;7:14–7. doi: 10.4103/0974-8490.147136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mossa JS, Al-Yahya MA, Al-Meshal IA. Medicinal Plants of Saudi Arabia. Riyadh: King Saud University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mossa JS, Al-Yahya MA, Al-Meshal IA. Medicinal Plants of Saudi Arabia. Riyadh: King Saud University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Yahya MA, Al-Meshal IA, Mossa JS, Al-Badr AB, Tariq M. Saudi Plants: A Phytochemical and Biological Approach. Riyadh: King Saud University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gazanfar Shahina AZ. Handbook of Arabian Medicinal Plants. Boca Raton, Florida, London, Tokyo: CRC Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaudhary SA. Flora of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Riyadh: Ministry of Agriculture and Water; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaudhary SA. Flora of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Riyadh: Ministry of Agriculture and Water; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alqahtani SM, Alkholy SO, Ferreira MP. Antidiabetic and anticancer potential of native medicinal plants from Saudi Arabia. In: Watson RR, Preedy V, Zibadi S, editors. Polyphenols in Human Health and Disease. London: Elsevier; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hammond JA, Fielding D, Bishop SC. Prospects for plant anthelmintics in tropical veterinary medicine. Vet Res Commun. 1997;21:213–28. doi: 10.1023/a:1005884429253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petrovska BB. Historical review of medicinal plants' usage. Pharmacogn Rev. 2012;6:1–5. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.95849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ali NA, Al-Rahawi K, Lindequist U. Some medicinal plants used in Yemeni herbal medicine to treat malaria. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2004;1:72–6. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cragg GM, Boyd MR, Grever MR, Schepartz SA. Pharmaceutical prospecting and the potential for pharmaceutical crops – Natural product drug discovery at the United States National Cancer Institute. Ann Mo Bot Gard. 1995;82:47–53. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis WH, Elvin-Lewis MP. Medicinal plants as sources of new therapeutics. Ann Mo Bot Gard. 1995;82:16–24. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tosun F, Kizilay CA, Sener B, Vural M, Palittapongarnpim P. Antimycobacterial screening of some Turkish plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;95:273–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Stasi LC, Oliveira GP, Carvalhaes MA, Queiroz M, Jr, Tien OS, Kakinami SH, et al. Medicinal plants popularly used in the Brazilian Tropical Atlantic Forest. Fitoterapia. 2002;73:69–91. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(01)00362-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akerreta S, Cavero RY, Calvo MI. First comprehensive contribution to medical ethnobotany of Western Pyrenees. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2007;3:26. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-3-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Francis Xavier T, Kannan M, Auxilia A. Observation on the traditional phytotherapy among the Malayali tribes in Eastern Ghats of Tamil Nadu, South India. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;165:198–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El-Alfy TS, Ezzat SM, Hegazy AK, Amer AM, Kamel GM. Isolation of biologically active constituents from Moringa peregrina (Forssk.) Fiori. (Family: Moringaceae) growing in Egypt. Pharmacogn Mag. 2011;7:109–15. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.80667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amin TT, Al-Mohammed HI, Kaliyadan F, Mohammed BS. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Al Hassa, Saudi Arabia: Epidemiological trends from 2000 to 2010. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2013;6:667–72. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(13)60116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahmoudvand H, Ezzatkhah F, Sharififar F, Sharifi I, Dezaki ES. Antileishmanial and cytotoxic effects of essential oil and methanolic extract of Myrtus communis L. Korean J Parasitol. 2015;53:21–7. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2015.53.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Sokari SS, Ali NA, Monzote L, Al-Fatimi MA. Evaluation of antileishmanial activity of albaha medicinal plants against Leishmania amazonensis. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:938747. doi: 10.1155/2015/938747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kyriazis ID, Koutsoni OS, Aligiannis N, Karampetsou K, Skaltsounis AL, Dotsika E, et al. The leishmanicidal activity of oleuropein is selectively regulated through inflammation- and oxidative stress-related genes. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:441. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1701-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ali NA, Al-Sokari SS, Mothana RA, Kourish M, Wagih M, Paul C, et al. In vitro antiprotozoal activity potential of some plant extracts from Albaha region. World J Pharm Res. 2016;5:338–46. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anwar S, Crouch RA, Awadh Ali NA, Al-Fatimi MA, Setzer WN, Wessjohann L. Hierarchical cluster analysis and chemical characterisation of Myrtus communis L. essential oil from Yemen region and its antimicrobial, antioxidant and anti-colorectal adenocarcinoma properties. Nat Prod Res. 2017;9:1–6. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2016.1277346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong R, Davis AM, Badley E, Grewal R, Mohammed M. Prevalence of Arthritis and Rheumatic Diseases around the World. A Growing Burden and Implications for Health Care Needs Division of Health Care and Outcomes Research Arthritis Community Research and Evaluation Unit (ACREU) Toronto Western Research Institute. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flemmig J, Kuchta K, Arnhold J, Rauwald HW. Olea europaea leaf (Ph.Eur.) extract as well as several of its isolated phenolics inhibit the gout-related enzyme xanthine oxidase. Phytomedicine. 2011;18:561–6. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2010.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takeda R, Koike T, Taniguchi I, Tanaka K. Double-blind placebo-controlled trial of hydroxytyrosol of Olea europaea on pain in gonarthrosis. Phytomedicine. 2013;20:861–4. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaur A, Nain P, Nain J. Herbal plants used in treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: A review. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2012;4:44–57. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mulwa LS. Doctoral Dissertation. Kenya: University of Nairobi; 2012. Phytochemical Investigation of Psiadia punctulata for Analgesic Agents. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahmad M, Imran H, Yaqeen Z, Rehman Z, Rahman A, Fatima N, et al. Pharmacological profile of Salvadora persica. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2011;24:323–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koheil MA, Mohammed A, Hussein MA, Othman SM, El-Haddad A. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of Moringa peregrina Seeds. Free Radic Antioxid. 2011;1:49–61. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Azzawie HF, Alhamdani MS. Hypoglycemic and antioxidant effect of oleuropein in alloxan-diabetic rabbits. Life Sci. 2006;78:1371–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Somova LI, Shode FO, Ramnanan P, Nadar A. Antihypertensive, antiatherosclerotic and antioxidant activity of triterpenoids isolated from Olea europaea, subspecies Africana leaves. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;84:299–305. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Algandaby MM, Alghamdi HA, Ashour OM, Abdel-Naim AB, Ghareib SA, Abdel-Sattar EA, et al. Mechanisms of the antihyperglycemic activity of Retama raetam in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010;48:2448–53. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phondani PC, Bhatt A, Elsarrag E, Horr YA. Ethnobotanical magnitude towards sustainable utilization of wild foliage in Arabian Desert. J Tradit Complement Med. 2015;6:209–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Youssef RS. Medicinal and non-medicinal uses of some plants found in the middle region of Saudi Arabia. J Med Plants Res. 2013;7:2501–13. [Google Scholar]

- 44.El-Ghazali GE, Al-Khalifa KS, Saleem GA, Abdallah EM. Traditional medicinal plants indigenous to Al-Rass province, Saudi Arabia. J Med Plants Res. 2010;4:2680–3. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rahman MA, Mossa JS, Al-Said MS, Al-Yahya MA. Medicinal plant diversity in the flora of Saudi Arabia 1: A report on seven plant families. Fitoterapia. 2004;75:149–61. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mandaville JP. A Dissertation. University of Arizona; 2004. Beduin Ethnobony: Plant Concepts and Plant Use in a Desert Pastoral World. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Arfaj AS. Hyperuricemia in Saudi Arabia. Rheumatol Int. 2001;20:61–4. doi: 10.1007/s002960000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]