Abstract

Governance is central to improving health sector performance and achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC). However, the growing body of research on governance and health has not yet led to a global consensus on the need for more investment in governance interventions to improve health. This paper aims to summarise the latest evidence on the influence of governance on health, examines how we can assess governance interventions and considers what might constitute good investments in health sector governance in resource constrained settings. The paper concludes that agendas for improving governance need to be realistic and build on promising in-country innovation and the growing evidence base of what works in different settings. For UHC to be achieved, governance will require new partnerships and opportunities for dialogue, between state and non-state actors. Countries will require stronger platforms for effective intersectoral actions and more capacity for applied policy research and evaluation. Improved governance will also come from collective action across countries in research, norms and standards, and communicable disease control.

Keywords: health policy, health systems, governance

Key questions.

What is already known about this topic?

Governance is central to improving health sector performance and achieving Universal Health Coverage.

What are the new findings?

There is a growing body of evidence about the effectiveness of strategies to strengthen health sector governance in low and middle-income countries, but greater synthesis of this information is required and it must be customised to local context.

There are emerging opportunities, but agendas must be realistic.

Promising local innovations include closer collaborations between civil society organisations, citizens and government, and more open access to information on performance in the health sector.

Recommendations for policy

For Universal Health Coverage to be achieved, health sector governance will require new partnerships and opportunities for dialogue, between state and non-state actors.

Countries will require stronger platforms for effective intersectoral actions, standardised measures of health sector governance, and more capacity for applied policy research and evaluation.

Improved governance can also come from collective action across countries, in areas such as medical research, norms and standards and communicable disease control.

Introduction

Governance has long been recognised as key to improving performance in the health sector of a country1 and, along with improving health financing and delivery of services, is central to achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC).2 There is a growing complex body of research and guidance on broader governance and on its relationship with health.3 However, in settings where resource constraints are most severe, many global health actors question whether investments in strengthening the governance of the health sector can reap benefits in terms of improved service coverage and outcomes. This paper aims to summarise some current debates in particular addressing the questions:

What is the evidence that strengthening governance improves health?

How can we assess the effectiveness of interventions to strengthen governance and improve health in the context of resource constrained, and poorly performing states?

What might constitute good investments in health sector governance

What do we mean by health sector governance?

‘Governance is defined as how societies make and implement collective decisions’.4 Its importance is recognised in the Sustainable Development Goals, where Goal 16 emphasises the need to ‘build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions’.5

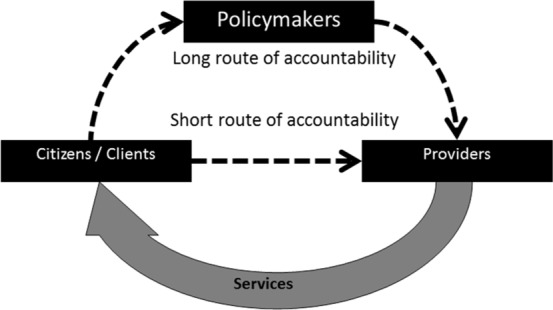

The processes of governance can be defined in many ways,6 but in the simplest terms, governance entails transferring some decision-making responsibility from individuals to a governing entity, with implementation by one or more institutions, and with accountability mechanisms to monitor and assure progress on the decisions made.7 Governing entities in the health sector can operate at different levels: global, national, subnational and local. The institutions responsible for implementation can be both formal, involving the public and non-state sectors, and informal, involving communities, work place and special interest groups. For health services, this process requires consideration of, as a minimum, three sets of actors and the relationship between them (see figure 1).8 Citizens are the ‘clients’ of service providers and ideally should be able to hold the provider accountable for services. However, accountability more usually is expected to come through government’s and other agencies’ relationships with providers. This may involve insurance funds, professional bodies, academic and training schools, accreditation agencies, donors and international development partners.

Figure 1.

Governance and making services work for the poor (Source World Bank, 2004).

Governance can be strengthened through improving the ‘short route’, or bottom–up form of accountability between clients and providers. This might be done by tailoring the services to specific needs, by local users becoming effective monitors of providers and by improving choice and participation. Governance can also be strengthened through improving the ‘long route’, or top–down form of accountability, by holding policymakers more accountable for services, and by making policymakers better positioned to influence the quality and coverage of services. This can, for example, be achieved through making information more accessible (on, eg, finances, performance or political commitments) and improving supply-side functions (eg, public financial management, human resources, information management and regulations of public–private partnerships).9 Both types of accountability are required for effective governance to be sustained.

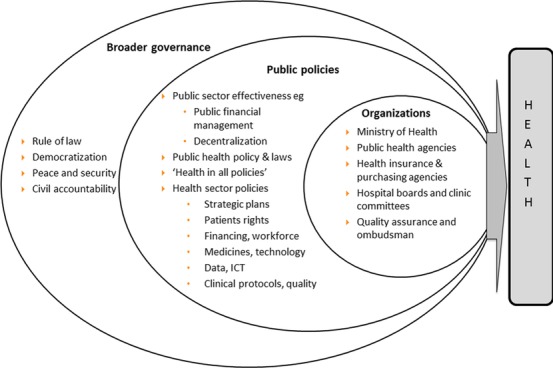

The link between governance and health can operate at multiple levels, including the broader governance environment, public policies both external and internal to the health sector and the effectiveness of organisations within the health sector that carry out specific governance-related tasks10 11 (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Governance and the health sector (adapted from Savedoff 2009).

Does stronger governance improve health?

The association between broader governance and health can be direct, for example, autocratic governments leading to increased famine mortality7, or indirect, through stronger governance across sectors that influences health and increased income.12 13 Composite measures of regulatory quality, rule of law and control of corruption are associated with decreases in infant mortality rates.14 In sub-Saharan Africa, spending can be twice as effective in improving under five mortality and increasing life expectancy where there is higher quality of governance,15 although the impact on equity is less clear.16 In low and middle-income countries, the impact of international development assistance for health is dependent on the quality of state institutions and policies.17 Democratic reforms, particularly if long lasting, are linked to improvements in health18 19 and UHC.20 However, this association is inconsistent7, and some countries without a democracy saw major progress against the Millennium Development Goals. Where broader governance breaks down, leading to conflict, war and the loss of peace and security, there is a major impact on health, through direct violence and injury, loss of social protection, poor nutrition, unsafe water as well as collapsing health systems. The impact can extend for many years after conflicts have ceased.21

Various public policies are associated with improved health in low and middle-income countries. Decentralisation, for example, can potentially improve responses to local needs, promote policymaking that empowers beneficiaries and community engagement that strengthens social capital (ie, trust and reciprocation)7. Strong public sector financial management associated with reduced corruption has been shown to improve the likelihood that increased public health spending improves health outcomes.22 23 There are health implications of governance in other sectors as is recognised in the call for ‘health in all policies’.24 Finally, the governance of specific health sector organisations may also affect health. More effective governance of the Ministries of Health, for example, can mobilise sufficient funds and ensure adequate infrastructure for the faster uptake of new technology such as vaccines.25 Effective governance of public health agencies, such as those overseeing screening and prevention or public health emergencies,26 is a key factor in their performance. Health service providers that are more accountable to local communities, via clinic committees or similar structures, can also lead to improved health outcomes.27 Our knowledge on how to improve responsiveness and accountability in resource poor settings continues to grow28 29.

How do we measure governance’s influence on health?

The multifaceted nature of governance means that it is not straightforward to assess how governance affects health. Frequently, studies investigating the effects of broad governance on health employ composite measures of governance,30 31 or democracy,32 the climate for private investment33 or corruption,34 as well as regionally defined measures.35 Some measures have been designed by the World Bank specifically to guide policymakers as to what actions they can take to strengthen governance.36

Health sector governance is similarly multifaceted and there is, as yet, no standardised methodology to conceptualise and measure governance and its influence on the performance of the health sector. However, it can be assessed through reviewing specific functions or principles such as arrangements for stakeholder participation in health planning processes, local health service accountability mechanisms, availability of information on provider performance, the clarity of health sector legislation, enforcement of health regulations and the availability of procedures to report misuse of resources.37 38 While many of these functions are common to other sectors, health information needs special attention given the high level of asymmetry of information in healthcare. Another approach to assessing health sector governance is to review the roles and responsibilities among key actors, such as politicians, policymakers, clients or citizens and providers of services.39 More focused assessments may use political economy analyses,40 assessment of participation or inclusion in decision making,41 and functional audits of key institutions and governing entities.42 The latter might include reviewing the functioning of parliamentary oversight committees,43 hospital boards44 and clinic committees,45 or mechanisms for overseeing particular health programmes. Assessing and improving governance for cross-sectoral interventions poses particular challenges, as can be seen with struggles to prioritise and coordinate action on early childhood development46 and improving nutrition.47

The choice of governance measure is determined by the reason for the assessment and the questions being asked.48 49 Measures of governance can be rules-based determinants (such as presence of policies, standards and laws) and / or more outcome-based performance measures (such as health worker absenteeism, proportion of government funds reaching district facilities, stock-out rates for essential drugs).11 Those undertaking research on governance in the health sector have proposed the use of common ‘governance results’, such as transparency, participation and policy capacity, to allow for a more rigorous comparison of different interventions.50 However, in many situations, outside of formal research, a pragmatic approach to assessing any governance arrangement is to use existing information to assess structure, whether governing entities are in place and functioning; process, whether decisions made are being implemented; and outcome to determine whether there is the desired improvement in performance or health outcomes.51

Towards an agenda for strengthening governance to improve health in resource poor states

In low and middle-income countries, a key question for the international health community is what is feasible to achieve in terms of improving governance if the broader political environment is not strongly supportive. In building a future agenda, we propose that four factors be considered.

Setting a realistic agenda

The list of interventions and ‘reforms’ required to strengthen governance can be long and daunting. Changes need to take into consideration local capacities and feasibility, and work towards ‘good enough’ rather than ideal conditions of governance.52 The agenda will vary according to local context and/or level of resources available. Well-accepted approaches focus on improving public sector effectiveness through a stronger civil service, improved audits, decentralisation and more local accountability.53 State institutions can be made more effective through a combination of stronger citizen engagement and improved public responsiveness.54 Such efforts, however, need to understand the importance of power and political will, as well as institutional capacity, in getting policies implemented.55 Corruption can be very high in the health sector,56 and there is growing evidence of which interventions work to reduce it.57 Research on corruption in the health sector of low-income settings is still quite limited, but does show that interventions depend on political commitment for their success.58

Different aspects of the health sector require their own governance mechanisms to be effective. For example, strategic purchasing for health requires governing entities to make decisions on the services, or benefits package, to be provided, on the roles of purchaser(s) and providers, as well as on the level of resources required to meet service entitlements.59 Similarly, governance mechanisms are important for strengthening the health workforce60 (such as accreditation, licensing and registration), improving access and procurement of essential drugs and medical supplies61 (using, eg, inspections and pharmacovigilance), and standardising health data and health information systems.62 There is growing experience of various governance arrangements that make service providers accountable for continuously improving the quality of their services.63

Exploring international standards for health sector governance

As the arguments and evidence base becomes stronger, so the international public health community will be able to explore and promote a broader set of governance standards for the health sector through global and regional agreements. A standardised methodology for assessing health sector governance is required. Some standards already exist informally through peer exchange, as with the changing role of Ministries of Health,64 and through more formal arrangements with international bodies, such as for Intellectual Property65 and health of migrant workers.66 Calls are already being made for a broader Framework Convention on Health covering accountability, financing, equity and intellectual property.67 WHO’s work on health laws and UHC is progressing.68 Other pragmatic steps could be made as international scientific evidence and consensus evolves. Lessons could also be drawn from other global efforts such as the Framework Convention for Tobacco Control69 and the Open Government Partnership.70 Introducing standards on freedom of information and transparency of health and health systems data could be an important next step.71

Building on promising innovation

Institutional rigidities and vested interests mean that frequently strengthening governance is challenging and likely to encounter resistance from powerful stakeholder groups. In this context, innovation in governance can be key, disrupting existing power structures, organisational cultures and patterns of behaviour. In recent years, there have been a number of promising innovations in health sector governance. There is a growing recognition of the potential for collaborations between civil society organisations, citizens and government to monitor different aspects of performance in the health sector and take actions to improve it.72 Another promising area is the growing use of digital technologies to promote transparency, strengthen decision making, mobilise citizens for accountability and automate audit processes.73 These two innovations are clearly synergistic, with digital technology facilitating the participation of non-traditional groups in governance. Robust evidence about the effectiveness of such strategies is still accumulating73, but does suggest that they can be effective if there are also shifts in government’s organisational culture74, including effective sanctions and not just more information.75

Finally, while innovation may be key to disrupting well-established but poor governance processes, most incentives in government systems militate against risk taking. Government systems need to adapt to both encourage risk taking and management of risk.76

Gathering evidence on what works

Making the case for additional health governance investments when resources are scarce can be difficult. This paper has documented the growing literature reporting primary research on strategies to strengthen health sector governance, and some of these papers have been systematically reviewed. However, more comprehensive review and synthesis of the evidence on what works in different situations, and the resource implications of these efforts, would help make the case. Certainly, evaluative studies of health governance interventions are important, but effective governance strategies are typically path dependent and context specific. As approaches are rolled out, they should be linked to careful research that both enables learning as to what works, and facilitates fine-tuning and adaption of the strategy.

Conclusions

Effective governance of the health sector is a critical foundation for improving health. For UHC to be achieved, health sector governance will require new partnerships and opportunities for dialogue, between state and non-state actors. Countries will require stronger platforms for effective intersectoral actions and more capacity for applied policy research and evaluation. Improved governance for health also requires collective action across countries, in areas such as medical research, norms and standards, and communicable disease control. Governance is too critical to the effectiveness of the health sector for us not to invest in it. Although health sector governance is unlikely to be perfect in any context, there are proven ways to strengthen critical aspects even in a context where broader governance is problematic. While there is a growing body of evidence about the effectiveness of strategies to strengthen governance in low and middle-income countries, greater synthesis of this information is required and it must be customised to local context. Standardised methodologies for assessing health sector governance are needed, and improved public access to health information should be an early objective. These agendas are all long term, but are important if the aspirations set by the goal of UHC are to become a reality.

Footnotes

Contributors: RF and SB contributed to sections of the final draft article and AS provide comments on final drafts prior to completion and submission. All read comments from reviewers and contributed to the amended version. For final draft, RF made changes and coauthors read and agreed to changes.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Health Systems-Governance WHO. http://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/stewardship/en/ (accessed Nov 8 2016).

- 2. Health Systems strengthening for UHC: building a shared vision. UHC 2030, Presentation, WHO, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. WHO EURO (WHO Regional Office for Europe). : Greer SL, Wismar M, Figueras J, Strengthening HealthSystem Governance: Better policies, stronger performance. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2016. WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 4. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Kosinska M Preface in ‘Strengthening Health System Governance: Better policies, stronger performance’. 2016. WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sustainable Development Goal 16: un. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg16 (accessed Nov 8 2016).

- 6. Barbazza E, Tello JE. A review of health governance: definitions, dimensions and tools to govern. Health Policy 2014;116:1–11. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ciccone DK, Vian T, Maurer L, et al. . Linking governance mechanisms to health outcomes: a review of the literature in low- and middle-income countries. Soc Sci Med 2014;117:86–95. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Making services work for the Poor. World Development Report. World Bank, 2004. Brinkerhoff D. Accountability and health systems: toward Conceptual clarity and policy relevance. Health Policy and Planning 2004;19:371–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brinkerhoff DW. Accountability and health systems: toward conceptual clarity and policy relevance. Health Policy Plan 2004;19:371–9. 10.1093/heapol/czh052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kickbusch I, Gleicher D. Smart governance for health and well-being: the evidence. WHO Regional Office forEurope, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Savedoff WD. Governance in the health sector: a strategy for measuring determinants and performance. Social Insight. Submitted to World Bank (accessed Nov 1 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 12. Klomp J, De Haan J. Effects of governance on health: a cross-national analysis of 101 countries. Kyklos;61:599–614. 10.1111/j.1467-6435.2008.00415.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Holmberg S, Rothstein B. Dying of corruption. Health Econ Policy Law 2011;6:529–47. 10.1017/S174413311000023X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lazarova EA. Governance in relation to infant mortality rate: evidence from around the world. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics 2006;77:385–94394. 10.1111/j.1467-8292.2006.00311.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Makuta I, O'Hare B, O’Hare B. Quality of governance, public spending on health and health status in sub Saharan Africa: a panel data regression analysis. BMC Public Health 2015;15:932 10.1186/s12889-015-2287-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Olafsdottir AE, Reidpath DD, Pokhrel S, et al. . Health systems performance in sub-Saharan Africa: governance, outcome and equity. BMC Public Health 2011;11:237 10.1186/1471-2458-11-237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Burnside C and David Dollar D. Aid, policies, and growth: revisiting the evidence. World Bank Policy Research Paper, Number O 2004;2834. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pieters H, Curzi D, Olper A, et al. . Effect of democratic reforms on child mortality: a synthetic control analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4:e627–e632. 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30104-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang Y, Mechkova V, Andersson F. Does Democracy or Good Governance Enhance Health? New Empirical evidence 1900-2012. University of Gothenburg: THE VARIETIES OF DEMOCRACY INSTITUTE September 2015; Working Paper SERIES 2015:11. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grepin KA, Dionne KY. Democratization and universal health coverage: a case comparison of Ghana, Kenya and Senegal. Volume VI: Global Health Governance, 2013. 2). Summer. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ghobarah HA, Huth P, Russett B. The post-war public health effects of civil conflict. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:869–84. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.11.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rajkumar AS, Swaroop V. Public spending and outcomes: does governance matter? J Dev Econ 2008;86:96–111. 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2007.08.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. World Bank. Wagstaff A and Mariam Claeson M. The Millennium Development Goals for health: Rising to the challenges 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Health in all policies: helsinki statement. framework for country action. WHO, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Glatman-Freedman A, Cohen ML, Nichols KA, et al. . Factors affecting the introduction of new vaccines to poor nations: a comparative study of the Haemophilus influenzae type B and hepatitis B vaccines. PLoS One 2010;5:e13802 10.1371/journal.pone.0013802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. WHO. A systematic review of Public Health Emergency Operations Centres (EOC). Who/hse/gcr/2014.1 Who 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Björkman M, Svensson J. Power to the people: evidence from a Randomized Field experiment on Community-Based monitoring in Uganda. Q J Econ 2009;124:735–69. 10.1162/qjec.2009.124.2.735 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cleary SM, Molyneux S, Gilson L. Resources, attitudes and culture: an understanding of the factors that influence the functioning of accountability mechanisms in primary health care settings. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:320 10.1186/1472-6963-13-320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lodenstein E, Dieleman M, Gerretsen B, et al. . Health provider responsiveness to social accountability initiatives in low- and middle-income countries: a realist review. Health Policy Plan 2017;32:czw089 10.1093/heapol/czw089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Worldwide governance indicators. World Bank. http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.aspx#home (accessed Nov 8 2016).

- 31. The Country Policy and Institutional Assessment (CPIA). http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/CPIA (accessed Nov 25th 2016).

- 32. Bertelsmann Transformation Index. Bertelsmann Institute. http://www.bti-project.org/home/ (accessed Dec 3 2016).

- 33. Political risk service group. https://www.prsgroup.com/ (accessed Nov 8 2016).

- 34. Corruption perception index. Transparency Institute. http://www.transparency.org/ (accessed Dec 3 2016).

- 35. Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG). http://mo.ibrahim.foundation/iiag/ (accessed Dec 3 2016).

- 36. Actionable governance indicators. World Bank. http://www.agidata.org/Site/Default.aspx (accessed Dec 3 2016).

- 37. Siddiqi S, Masud TI, Nishtar S, et al. . Framework for assessing governance of the health system in developing countries: gateway to good governance. Health Policy 2009;90:13–25. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Health Systems 20/20. The Health System Assessment Approach: a How-To Manual. version 2.0. 2012. www.healthsystemassessment.org

- 39. Derick W Brinkerhoff DW, Bossert TJ. Health governance: principal–agent linkages and health system strengthening. Health Policy and Planning 2013:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Harris D. Applied political economy analysis A problem-driven framework. Overseas Development Institute 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Berlan D, Shiffman J. Holding health providers in developing countries accountable to consumers: a synthesis of relevant scholarship. Health Policy Plan 2012;27:271–80. 10.1093/heapol/czr036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Galinsky DG, Schweitzer ME. The ups and Downs of managing hierarchies: the Keys to organizational effectiveness. leadership & managing people Case Study. Harvard Business Review 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Experiences of parliamentary committees on Health in promoting health equity in East and Southern Africa. Regional Network for Equity in Health in east and southern Africa (EQUINET). Discussion 2009;73. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jha A, Epstein A. Hospital Governance and the Quality of Care. Health Aff 2010;29:182–7. 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lodenstein E, Dieleman M, Gerretsen B, et al. . Health provider responsiveness to social accountability initiatives in low- and middle-income countries: a realist review. Health Policy Plan 2017;32:125–40. 10.1093/heapol/czw089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shawar YR, Shiffman J. Generation of global political priority for early childhood development: the challenges of framing and governance. Lancet 2017;389:119–24. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31574-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sunguya BF, Ong KI, Dhakal S, et al. . Strong nutrition governance is a key to addressing nutrition transition in low and middle-income countries: review of countries' nutrition policies. Nutr J 2014;13:65 10.1186/1475-2891-13-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lewis M, Pettersson G. Governance in health care delivery: raising performance. World Bank, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 49. WHO. Health systems governance: toolkit on monitoring health systems strengthening. Geneva 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Greer SL, Wismar M, Figueras J. Introduction: strengthening governance amidst changing governance : Strengthening Health System Governance: better policies, stronger performance’. WHO: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Savedoff WD, Smith PC. Measuring governance: accountability, management and research ‘Strengthening Health System Governance: Better policies, stronger performance’. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. WHO, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Grindle MS. Good enough governance: poverty reduction and reform in developing countries In: Governance: an International Journal of Policy, Administration and Institutions. 17, 2004:525–48. No 4 10.1111/j.0952-1895.2004.00256.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Carothers T, Brechenmacher S. Accountability, Transparency, Participation and Inclusion. A new developmentconsensus? Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fox J. Social accountability: what does the evidence really say? Global Partnership for Social Accountability. GPSA working paper 2014;1. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Report WD. Governance and the law (forthcoming). 2017. http://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2017 (accessed Feb 14 2017).

- 56. Vian T. Review of corruption in the health sector: theory, methods and interventions. Health Policy Plan 2008;23:83–94. 10.1093/heapol/czm048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gaitonde R, Oxman AD, Okebukola PO, et al. . Interventions to reduce corruption in the health sector. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;8:CD008856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Huss R, Green A, Sudarshan H, et al. . Good governance and corruption in the health sector: lessons from the Karnataka experience. Health Policy Plan 2011;26:471–84. 10.1093/heapol/czq080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. What is strategic purchasing? RESYST 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hastings SE, Armitage GD, Mallinson S, et al. . Exploring the relationship between governance mechanisms in healthcare and health workforce outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:479 10.1186/1472-6963-14-479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pezzola A, Sweet CM. Global pharmaceutical regulation: the challenge of integration for developing states. Global Health 2016;12:85 10.1186/s12992-016-0208-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Health data standards, WHO. http://www.searo.who.int/entity/health_situation_trends/topics/health_data_standrads/en/ (accessed Dec 3 2016).

- 63. Governing quality in health care on the path to universal health coverage: a review of the literature and 25 country experiences. Health Finance and Governance Project 2015. https://www.hfgproject.org/governing-quality-health-care-path-universal-health-coverage-review-literature-25-country-experiences/ (accessed Feb 14 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 64. Omaswa F, Boufford JI. Strong ministries for Strong Health Systems. handbook for minsters of Health. Makere University, 2014. ISBN: 978-9970-35-004-9. [Google Scholar]

- 65. TRIPS and Public Health. World Trade Organisation. https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/pharmpatent_e.htm

- 66. International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workersand Members of Their Families. 2003. (arts. 28, 43, 45 and 81) adopted 1990. entered into force in 2003.

- 67. Ooms G, Hammonds R. Global constitutionalism, applied to global health governance: uncovering legitimacy deficits and suggesting remedies. Global Health 2016;12:84 10.1186/s12992-016-0216-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. WHO’s work on laws and universal health coverage. http://www.who.int/health-laws/who-work/en/ (accessed Dec 3 2016).

- 69. Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. http://www.who.int/fctc/en/ (accessed Dec 3 2016).

- 70. Open Government Partnership. Independent Reporting mechanism (IRM). http://www.opengovpartnership.org/irm/irm-reports (accessed 3 Dec 2016).

- 71. Health data collaborative. https://www.healthdatacollaborative.org/ (accessed Dec 3 2016).

- 72. Bloom G, Henson S, Peters DH. Innovation in regulation of rapidly changing health markets. Global Health 2014;10:53 10.1186/1744-8603-10-53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Holeman I, Cookson TP, Pagliari C. Digital technology for health sector governance in low and middle income countries: a scoping review. J Glob Health 2016;6:020408 10.7189/jogh.06.020408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Isett KR, Miranda J. Watching Sausage being made: lessons learned from the co-production of governance in a behavioural health system. Public Management Review 2015;17:35–56. 10.1080/14719037.2014.881536 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Fox JA. Social Accountability: what does the evidence really say? World Dev 2015;72:346–61. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.03.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Brown L, Osborne SP. Risk and innovation: towards a framework for risk governance in the public services. Public Management Review 2013;15:186–208. [Google Scholar]