Abstract

Two key components of end-of-life planning are (1) informal discussions about future care and other end-of-life preferences and (2) formal planning via living wills and other legal documents. We leverage previous work on the institutional aspects of marriage and on sexual-minority discrimination to theorize why and how heterosexual, gay, and lesbian married couples engage in informal and formal end-of-life planning. We analyze qualitative dyadic in-depth interviews with 45 midlife gay, lesbian, and heterosexual married couples (N = 90 spouses). Findings suggest that same-sex spouses devote considerable attention to informal planning conversations and formal end-of-life plans, while heterosexual spouses report minimal formal or informal planning. The primary reasons same-sex spouses give for making end-of-life preparations are related to the absence of legal protections and concerns about discrimination from families. These findings raise questions about future end-of-life planning for same- and different-sex couples given a rapidly shifting legal and social landscape.

Keywords: aging, dyadic qualitative analysis, end-of-life planning, marriage, sexual minorities

Scholars, policy makers, and healthcare workers emphasize the importance of end-of-life planning as a way to enhance the quality of later-life caregiving, health, and death (Institute of Medicine 2014). Better end-of-life planning benefits the well-being of the dying as well as bereaved family members and friends. Two key components of end-of-life planning are (1) informal conversations with loved ones about future care and end-of-life preferences and (2) the creation of formal end-of-life plans via living wills, healthcare proxies, and other legal documents (Bischoff et al. 2013; Sudore and Fried 2010). Informal and formal planning ideally commences long before the end of life and is most beneficial when implemented in midlife before people are confronted with debilitating conditions or difficult decisions (Institute of Medicine 2014). Despite these benefits, one recent study suggests that only about one fourth of midlife adults have advance care directives (Rao et al. 2014).

Notably, among the married, spouses are typically charged with providing care and making end-of-life decisions (Carr and Khodyakov 2007). Yet, despite ongoing interactions between spouses, most research on end-of-life planning considers the perspective of only one spouse (Perkins, Cortez, and Hazuda 2004). Moreover, research on end-of-life planning within marriage has focused almost exclusively on heterosexual spouses (for an exception, see Riggle, Rostosky, and Prather 2006), despite evidence that many processes thought to be normative in different-sex marriages operate differently in same-sex marriages (Reczek and Umberson 2016; Umberson et al. 2016). Because gay and lesbian spouses experience higher levels of discrimination, stigma, and minority stress and lower levels of institutional support compared to heterosexual couples (LeBlanc, Frost, and Wight 2015; Umberson et al. 2015), gay and lesbian spouses’ end-of-life discussions likely unfold differently than those of heterosexual spouses. Future planning is especially important for same-sex couples in light of sexual-minority health disparities, including higher rates of chronic and acute disease, particularly among older adults (Institute of Medicine 2011). Notably, both recent U.S. Supreme Court cases on same-sex marriage concerned end-of-life issues, highlighting illness and later life as a time when marriage is particularly salient (Obergefell v. Hodges 2015; United States v. Windsor 2013). However, prior studies have not included both same-sex and different-sex married couples, precluding comparisons across couples.

In the present study, we leverage previous work on the institutional aspects of marriage and on sexual-minority discrimination to theorize why and how heterosexual, gay, and lesbian married couples engage in informal and formal end-of-life planning. We use dyadic qualitative methods to analyze in-depth interview data from both spouses in midlife gay, lesbian, and heterosexual marriages (90 spouses in 45 marriages) with the goal of reframing assumptions about end-of-life planning based on heterosexual marriages. We compare the responses of men and women in same-sex and different-sex marriages and consider the ways in which end-of-life and future care discussions and plans may be shaped by the social norms and legal protections of marriage as well as experiences and expectations of discrimination. We posit that formal and informal end-of-life planning unfolds differently for same-sex and different-sex spouses due to different incentives and disincentives that result from the institutional aspects of marriage and sexual minority discrimination.

BACKGROUND

Institutional Aspects of Marriage

Marriage—specifically, heterosexual marriage—is a primary social and legal institution in the U.S. (Cherlin 2004; Thomeer and Short forthcoming). As an institution, marriage involves socially established and legally sustained patterns of norms, roles, values, and behaviors that provide spouses with informal guides to their roles and obligations (Cherlin 1978), with important implications for end-of-life and future care planning. One key aspect of the marital institution, reflected in traditional wedding vows, is the expectation that spouses will provide care and support for each other in sickness and in health. Yet these very norms may interfere with actually discussing and planning such care prior to serious illness or infirmity. Studies find that married older adults often do not know their spouse’s end-of-life preferences but rather project their own preferences onto their spouse (Moorman and Carr 2008; Moorman, Carr, and Boerner 2014; Moorman, Hauser, and Carr 2009). These projections may be especially likely if spouses have not discussed end-of-life preferences (Gardner and Kramer 2010; Moorman et al. 2009; Song et al. 2005). Another key institutional aspect of marriage is the legal procedures automatically in place following marriage. In the absence of a will, the living spouse inherits property and financial resources in accordance with estate law (Chambers 1996). Hospitals and medical organizations grant spouses important rights that facilitate their care for one another, such as hospital visits and inclusion in care decisions. Legal protections afforded to married couples may serve as disincentives for creating formal end-of-life plans (e.g., healthcare proxies).

Family scholars argue that institutional aspects of marriage do not apply equally to all couples (Cherlin 1978; Hull 2006). For instance, Cherlin (1978) has argued that remarriages are characterized by weaker norms regarding how spouses and children should behave toward one another. As a relatively new status, same-sex marriage may be a weaker institution than heterosexual marriage, and the norms and roles characteristic of heterosexual marriages may be less salient to gay and lesbian couples (Cherlin 2004). The institution of marriage may be particularly weak for midlife and older same-sex married couples, who are more likely than heterosexual couples to have begun and spent a longer period of their relationship outside the legal institution of marriage (Umberson et al. 2015). Additionally, same-sex couples may be more likely to have practical and symbolic critiques of the institution of marriage—for example, the belief that marriage is an oppressive and constraining social institution (Lannutti 2005, 2011). This could lead to lower expectations for legal protections from the state regarding end-of-life events. Thus, same-sex couples’ marriages may be less strongly institutionalized and characterized by weaker (or at least different) norms and social roles than their heterosexual couple counterparts.

The weaker institutionalization of marriage for same-sex compared to different-sex couples may contribute to different incentives and disincentives for end-of-life planning conversations and formal plans. Having fewer assumptions regarding what care spouses will provide and lower expectations for protections from the state may incentivize same-sex spouses to engage in more informal discussions and to implement end-of-life plans. At the same time, weaker institutionalization may also mean same-sex couples are less likely to expect care from spouses, a traditional norm within marriage. But because so little research has been done on same-sex marriage, the norms and expectations related to end-of-life plans may not differ for same-sex marriages compared to different-sex marriages.

Discrimination

Even within state-sanctioned marriage, same-sex marriages may be less recognized and protected than heterosexual marriages. U.S. culture is still largely heteronormative and homonegative, meaning that heterosexual unions are revered as the gold standard. In turn, gay and lesbian unions still face considerable discrimination from individuals (e.g., family members), organizations (e.g., wedding photographers), and institutions (e.g., international adoption laws) (LeBlanc, Frost, and Wight 2015). Even in the context of legal marriage, same-sex spouses may worry about encountering discrimination and take proactive steps to protect themselves at the end of life. Indeed, studies find that gay and lesbian adults are more likely to have advance care directives and other legal documents for end-of-life care than are heterosexual adults, partly due to concerns about healthcare providers not respecting their wishes (Harding, Epiphaniou, and Chidgey-Clark 2012; Hash and Netting 2007; Rawlings 2012). Because heterosexual couples likely do not share these same concerns (i.e., worrying that their marriage will not be officially recognized by healthcare providers), they may be less motivated to formally or informally participate in end-of-life planning. Conversely, concerns over discrimination due to sexual orientation may make gay and lesbian spouses wary of trying to go through the formal steps of establishing legal protections, such as meeting with a lawyer (Rawlings 2012; Riggle and Rostosky 2005; Rostosky et al. 2016).

Discrimination in family contexts is also relevant to end-of-life and future care planning, manifesting as family interference and lack of family support at the end of life. Same-sex couples’ extended families are more likely to raise questions about relationship legitimacy, and same-sex couples are more likely to have strained ties with family members and to have fewer family confidantes (Balsam et al. 2008; Moore and Stambolis-Ruhstorfer 2013; Powell et al. 2010; Reczek 2014, 2015; Rostosky et al. 2004). Moreover, same-sex couples are less likely than different-sex couples to have adult children. In 2013, an estimated 19% of same-sex couples were raising children under the age of 18 compared to 42% of different-sex married couples (Gates 2014). Different-sex couples heavily rely on their adult children for caregiving and assistance with end-of-life needs (Carr and Khodyakov 2007; Pinquart and Sörensen 2011), an option less available to this current cohort of midlife same-sex couples. At the same time, according to the families-of-choice perspective, same-sex couples historically draw on friends for support more than different-sex couples do (Dewaele et al. 2011; LeBlanc, Frost, Alston-Stepnitz et al. 2015; Weston 1991), which may serve as a counterbalance for lower levels of family support.

DATA AND METHOD

Data

We analyzed dyadic data from in-depth interviews with both spouses (90 individuals) in 15 gay couples, 15 lesbian couples, and 15 heterosexual couples from the Massachusetts Health and Relationship Project. The study was designed to consider how midlife spouses in same- and different-sex marriages influence each other’s health. The present study analyzed portions of the interviews that asked about late-life illness and care plans. All respondents were ages 40 to 60 years (mean age = 50.2 years) and legally married for a minimum of 7 years (mean relationship duration, including time cohabiting and married = 21.3 years). More information on the sample composition is in Table 1. All respondents were residing in Massachusetts at the time of the study (2012–2013). Massachusetts was selected as the study site because it was the first state in the United States to legalize same-sex marriage in 2004 and thus had a considerable population of married same-sex couples at the time of the study. Notably, at the time of the interviews, same-sex marriage was not federally protected and was not legal in the majority of U.S. states.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Respondents from Massachusetts Health and Relationship Project (N = 90 individuals; 2012–2013).

| Variable | Gay Couples (n = 30 individuals) | Lesbian Couples (n = 30 individuals) | Heterosexual Couples (n = 30 individuals) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, years) | 49.70 | 51.00 | 49.93 |

| Relationship duration (mean, years) | 19.33 | 20.33 | 23.60 |

| Children (%) | 13 | 40 | 80 |

| Education | |||

| High school/some college (%) | 7 | 13 | 23 |

| College degree (%) | 33 | 20 | 30 |

| Postgraduate/professional (%) | 60 | 67 | 47 |

| Informally discussed future plans (%) | 67 | 73 | 33 |

| Formal documents in place (%) | 67 | 80 | 47 |

The analytic sample, although not representative of the U.S. population, was recruited through a systematic design to create comparable groups of gay, lesbian, and heterosexual spouses, particularly in age and relationship duration. First, same-sex couples married between 2004 and 2006 and meeting the age requirements were identified through marriage records at the Massachusetts Vital Records office, and a random sample was invited to participate via letters mailed to the addresses in those records. A random sample of different-sex couples who were married during this same period and also met the age requirements from the marriage records was also identified. We mailed letters to the each couples’ address listed in the records; when letters were returned because of incorrect mailing addresses, we tried to find couples’ current mailing address through other means (e.g., Internet search) and, if residing in Massachusetts, mailed a second letter. Second, respondents were asked to refer both same- and different-sex married couples from their social networks with an emphasis on recruiting couples of a similar age. The majority of same-sex couples were identified through Massachusetts marriage records, and the majority of different-sex couples were identified through referrals.

Method

In-depth interviews were conducted separately with each spouse (to ensure privacy and confidentiality) and included open-ended questions about end-of-life discussions and plans. We use pseudonyms to protect confidentiality. Interviewers used the same interview guide for all respondents and asked follow-up questions when appropriate. Spouses were asked whether they had formal legal protections in place (e.g., power of attorney, healthcare proxy) and whether they had informal conversations with their spouse about end-of-life and future care plans. For example, we asked, “Have you discussed or made arrangements for power of attorney in the event you couldn’t make medical decisions for yourselves?” and “Have you and your spouse ever talked about what you would do if one of you became disabled or mentally impaired, for example, with Alzheimer’s?” If they responded yes to these questions, they were asked for specifics about the plans they had made; if they responded no, they were asked, “Why do you think you haven’t talked about this?” We also asked about expectations for support, including “If you were suddenly faced with a severe medical crisis that required a lot of care at home, what kinds of support could you rely on [your spouse] for?” as well as questions regarding what kind of support they could rely on friends or family for. After we obtained basic information about end-of-life and care planning, we asked questions to understand their motivations for discussing these plans. For example, respondents were asked, “Have you ever been afraid that a parent or other family member might step in and try to influence medical decisions if you or your partner were ill?” and if yes, respondents were asked to tell the interviewer about those concerns. Respondents were also asked about previous health events during their relationship; past and current provisions of support for friends and families, especially aging parents; and how marriage changed their relationship with their spouse.

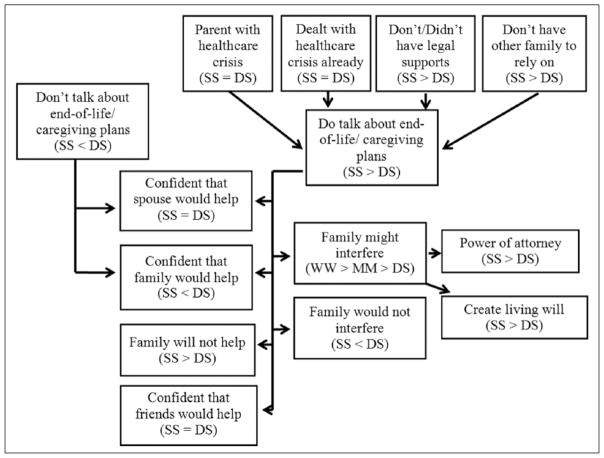

All interviews were independently analyzed by the authors using a standardized method of inductive data analysis that emphasizes the dynamic construction of codes for the purpose of developing analytical and theoretical interpretations of data (Silverman 2006). The authors performed the analysis with the assistance of QSR International NVivo 9 qualitative software. The authors used inductive reasoning to guide the coding and analysis, identifying patterns and conceptual categories as they emerged from the transcripts. The authors read the transcripts multiple times to ensure understanding of the content of the interviews and then followed a three-step coding process. First, the authors extracted all passages relevant to the research questions. The authors independently conducted line-by-line, construct-driven categorization in order to summarize each extracted piece of data as it related to the end-of-life discussions and plans of one or both spouses. Next, the authors performed “focused” coding to develop categories regarding informal end-of-life conversations, formal end-of-life conversations, and expectations for end-of-life support. Intercoder reliability was established (Miles and Huberman 1984), and the authors developed a standardized codebook based on the focused codes. Codes included, for example, “expect that family would provide support at the end of life” and “frequently discuss end-of-life plans with spouse.” In the final stage of analysis, the first author in consultation with the other authors created categories and subcategories that related to one another on a theoretical level; the themes from this final stage are discussed below and shown in Figure 1. In this stage, the first author also examined systematic differences across couple types and how the themes related to one another. The authors verified theoretical saturation—achieved when no new themes regarding end-of-life planning emerged and when existing themes had sufficient data—during this multistage coding process (Charmaz 2014).

Figure 1.

Qualitative Analysis Themes. Note: SS = same-sex couples; DS = different-sex couples; WW = woman-with-woman couples; MM = man-with-man couples. Greater-than sign (>) means more of that couple type present in that theme; less-than sign (<) means fewer of that couple present in that theme; equal sign (=) means similar representation across couple types.

RESULTS

Respondents were asked about their end-of-life and future care discussions, including how and why spouses discuss end-of-life plans, why spouses do or do not have formal end-of-life protections in place, whether they expect their spouse to support them if they experienced a debilitating illness, and how they expect their family to interact with them during this time. Most respondents said that they had informally discussed end-of-life and future care plans with their spouse to some extent and/or had formal measures in place, and almost all respondents expected their spouse to provide end-of-life support. Yet strong differences between same-sex and different-sex couples emerged when considering themes related to why and how respondents discussed plans, the role of family and friends in plans, and formal advance care–planning measures. These themes, and how they are related to each other, are shown in Figure 1 and discussed in detail below, and the prevalence of informal conversations and formal documents by union type is shown in Table 1.

Informal Conversations

Content of informal conversations

Over two thirds of respondents in gay and lesbian marriages and about one third of respondents in heterosexual marriages said that they had discussed future plans with their spouse. These conversations typically included how they would support their spouse and how respondents would want to be supported by their spouse at the end of life. Most lesbian and gay spouses described very extensive and detailed conversations, whereas most heterosexual spouses described these conversations as more limited. Further, many same-sex couples’ portrayed their conversations as frequent and common-place. In these discussions, same-sex spouses often drew on hypothetical situations. For example, Michael (married to David) said,

Let’s say David got Alzheimer’s. I often think [the nursing home] is a block and a half from here. It’s a pretty high quality care facility and at some point with Alzheimer’s it is just too taxing to do it by yourself at home. And we probably can’t afford to bring in round the clock care. … I think we’ve talked it through pretty thoroughly.

Same-sex couples also often discussed multiple scenarios, including contingency plans in case their ideal scenarios did not work out. Jill (married to Carolyn), said,

We talk about it all the time. … So when I have dementia, I’m comfortable with a nursing home. I’ve let her know that, but I think that we would both try to keep each other home as long as we could. … But when you can’t do it, you can’t do it, and we’re both very well aware of it.

Carolyn, in her own interview, concurred, saying, “It’s a constant conversation. … We’ve made our wishes quite clear.”

In contrast, for most respondents in heterosexual relationships—and a small number of spouses in gay relationships—these discussions, if they occurred, were described as less frequent and with fewer concrete plans. Wendy (married to Sean) said that any discussions they had were “very abstract.” When Penny (married to Ralph) was asked if she talked about end-of-life plans with her spouse, she said, “Have we talked about what happens? Well I guess we kind of talk about it,” but was unable to describe in detail any of their conversations. Respondents in heterosexual relationships also more often dismissed the question with humor. For example, when Peg (married to Nick) was asked if they had discussed what to do for one another if dealing with a difficult condition at the end of life, Peg said, “I told him to put me out. I said just put me out of my misery, and he wants the same thing.” Cindy (married to Dean) also dismissed the question with humor, stating, “I keep telling him he can’t die before me.”

Motivations for informal conversations

Our analysis revealed four main subthemes regarding why midlife respondents discussed end-of-life plans: (1) parents (or in-laws) recently had a health crisis, (2) respondent (or spouse) previously dealt with a health crisis, (3) no legal supports (e.g., legal marriage) in place at beginning of relationship, and (4) no other family to rely on. The first two were present across gay, lesbian, and heterosexual relationships, whereas the last two were present only in gay and lesbian relationships.

Many respondents who discussed end-of-life plans said they did so because they had seen their parents experience a health crisis—and in many cases had actively provided care for their aging parents—or because they had experienced their own health crisis, such as a serious chronic condition. Both situations gave respondents insight into what they did or did not want their end-of-life experience to be and made respondents more aware of their mortality. Michael (married to David), who said they had discussed their end-of-life plans “pretty thoroughly,” said that they had these discussions because:

[we] witnessed [physical and cognitive decline] with my mom and a little bit with David’s father, my mom, and stepfather. David and I talked about that and talked about how much more rational and maybe an equally loving model for how to take care of somebody in decline.

Similarly, Todd (married to Craig) noted that anticipating his parents’ caregiving needs made him realize how important it was to prepare for multiple scenarios with his spouse, including caregiver exhaustion:

We’ve talked about it, not at any great length, as in the details, but the other would be the caregiver as much as possible until it’s not wise to do so. Especially with reading up for my parents that we’ve found that everything says you can be a caregiver to a point. It comes to a point that it ruins both of you and you need to be aware of that and it’s a hard decision to make when you get there.

Serious health events within the couple also provided impetus for informal end-of-life discussions. Roger and Patrick were both HIV positive, and Patrick had stage IV tongue cancer. Patrick noted that because of these health conditions, they had “pretty frank and open conversations early on.” Due to these conversations, Patrick said, “I know without question what Roger’s wishes are if he were dealing with X, Y, or Z. And conversely he knows what my wishes are, too. And they’re pretty much in line.” Similarly, Katie (married to Sarah) said, “We talked about it a little bit, especially if my back or if her Crohn’s gets worse, what we are going to do. … We just, we’ll take care of each other as much as we can. We’ll go into nursing homes, no, senior citizen complex, and just take care of each other.”

Two subthemes were unique to gay and lesbian couples: “no legal supports in place” and “no other family to rely on.” Almost all the gay and lesbian couples who discussed end-of-life plans mentioned that beginning their relationship without the option of marriage and concerns over discrimination motivated their discussions. Debbie (married to Karen) said they frequently discussed end-of-life plans together, stating that not being able to legally marry was “the impetus for us to figure out some of this maybe younger than more traditional married couples do because they probably feel, whether it’s correct or not, they probably feel like ‘oh the law will protect us.’”

Many respondents in gay and lesbian marriages (although not the majority) mentioned that because of absent or strained relationships with extended family, they felt they had only one another to rely on and thus needed to explicitly discuss end-of-life plans. In some cases, they felt they did not have family to rely on because they did not have children. When asked whether they had other people to rely on in the event of a serious debilitating illness, Aaron (married to James) said, “I don’t know. I don’t think so. I don’t have kids. My family is older. My sister is 2,000 miles away.” This lack of family support did not concern Aaron, as he said he knew from his conversations with James that if this situation did arise, “I would take care of him. … If the answer to that question is no, what am I doing being married to him?” Karen (married to Debbie) discussed the rejection she and her wife experienced by family members because of their sexuality; Karen said, “Neither one of us has close relationships with our families.” This motivated more planning conversations, but as with Aaron and James and many other same-sex couples, this did not worry them. Karen said, regarding her lack of family ties and end-of-life plans, “There’s just kind of this thing that’s always there that if something serious happened that we have to have each other to rely on and that would probably be it.”

Motivations for no informal conversations

In contrast to detailed end-of-life discussions, about twice as many respondents in different-sex compared to same-sex marriages said they had not discussed end-of-life plans. Sherrie (married to Jeremy) said, “I guess it’s one of those things that I just don’t want to think about and he hasn’t either, so we haven’t talked about it. … As far as going into a nursing home or something like that, I don’t, I haven’t thought about it.” Beverly (married to Stan) said, “We haven’t talked about it.” When asked why not, she said, “I think maybe a little denial. I think my dad died in December and he had Alzheimer’s for a couple of years and [Stan’s] mother is 95 and I think it would be very sad to think about it.”

Some couples did not have conversations about end of life because one spouse actively resisted these conversations. Bradley (married to Samuel) said they had not discussed end-of-life plans:

I think because Samuel’s attitude is “What’s the point in talking about it?” because you know we don’t have any control of whether it’s going to happen or not. Let’s deal with it when we have to deal with it.

These dynamics can cause tension in relationships. For example, Kevin (married to Joe) stated that his spouse would try to bring up these topics and Kevin would resist. Kevin said that his avoidance of talking about the end of life was “probably one of the biggest stresses in our lives though it’s not a talked-about stress for the most part.”

Formal End-of-life Measures

Motivation for formal end-of-life measures

Respondents were asked about formal end-of-life preparations, including establishing their spouse as their healthcare proxy or creating a living will. Most of the same-sex couples, but fewer than half of heterosexual couples, said they had these measures in place. Our analysis revealed two main subthemes regarding why respondents established formal end-of-life measures: (1) did not have access to legal marriage (only found for gay and lesbian relationships) and (2) worried about family interference (found primarily in lesbian relationships). For the gay and lesbian couples, these documents were created in the early stages of their relationship, before legal access to marriage. Linda (married to Melissa) said, “The minister before we had our commitment ceremony made us promise to do living wills and healthcare proxies and all that stuff, which we did and then we updated it and then when the law changed we updated again.” Patrick (married to Roger) said,

The healthcare proxy stuff is what really started us in the direction of making our relationship somehow legally connected because I very much worried that not being able to visit in the hospital, not being able to make emergency decisions, that sort of thing.

Some of the couples mentioned being less concerned now that they were legally married. Todd (married to Craig) said, “Yeah, we did all those kinds of documents, and we used to keep them, you know, carry all those documents at one time. We don’t carry them anymore.”

Nearly all of the same-sex couples without these legal protections in place discussed plans to create them. Kathy (married to Melissa) said, “We started it on multiple occasions but never completed them. We have handwritten stuff down in the basement. We have a death file downstairs.” Yet, respondents in heterosexual marriages without legal documents mostly dismissed the question. When asked about power of attorney or living wills, Danielle (married to Levi) said, “Don’t want to think about it. … I can’t imagine life without him. I need to grow up from that mentality.” Cliff (married to Krissy) said, “It’s just one of those things that never really came up. We’ve never really sat down and thought about it.”

In addition to concerns about their legal status, for some couples, another motivator for these protections was worries about family interference, especially (for gay and lesbian couples) in the absence of federal protections. This was more common among lesbian respondents than others, as over half of lesbian respondents mentioned this worry, compared to only one sixth of gay respondents and only one heterosexual respondent. Debbie (married to Karen) said,

Because our families are not supportive, we were worried if something happened to one of us that our families would take over and it would be bad. … Our marriage doesn’t mean much outside of Massachusetts. I mean it is a social signifier but legally it means virtually nothing at a federal level.

Craig (married to Todd) said, “He worries more about that with my mom than I do with his, but both of us have healthcare proxies already written out to try and resolve that.” For many gay and lesbian respondents, marriage relieved concerns about family interference, even though their legal bond was recognized only in Massachusetts and not at the federal level. Sally (married to Heidi) said, “That was one of the nice offshoots I think of getting married. I think both of our families are exceptionally respectful … would in no way think of interfering at all.” Similarly, Sarah (married to Katie) said, “I think my family would defer to Katie. There’s kind of an explicit respect that she is my wife.” Almost none of the respondents in heterosexual couples were concerned about family interference. Bruce (married to Penny) said, “I don’t worry about that too much mostly because my parents and I, I think, have a relationship that if it had something to do with Penny, I could just say back off.”

Expectations for End-of-life Support

Respondents were asked about their own expectations for support in the event of debilitating illness. Four primary subthemes emerged from this question: (1) confident that spouse would provide support; (2) confident that family, including children, would provide support; (3) confident that family would not provide support; and (4) confident that friends would provide support.

Most respondents were confident that their spouse would care for them, regardless of whether they discussed end-of-life care with their spouse. When asked if he would support his spouse in the event of serious illness, Jeremy (married to Sherrie) said, “We haven’t talked about this aspect. But I think, ‘Yes, of course we will take care of each other.’” Similarly, Martin (married to Vincent) said, “We haven’t openly discussed it but I’m pretty sure if one was sick the other would be right there.” For couples who had not explicitly discussed future care, this confidence reflected views of their spouse’s character, evidence that they had supported their spouse during a past illness, and/or recognition that this was something spouses just did for each other. Judith (married to Gloria) said they had not discussed plans “other than the expectation that we’ll be there for each other. And so you deal with whatever gets thrown at you. And that has always with whatever in life has popped up.” Judith later cited the help her spouse provided during her mother’s illness as further evidence that her spouse would support her if needed, although they had not explicitly discussed this. Curtis (married to Annette) also responded that he had not discussed future care with his spouse but said they would support each other because “that’s what you do. If someone is sick and at home, you just go and take care of them. You really have no choice … not a question of comfort or uncomfortable; you just, there you go, you do it.”

The other subthemes related to end-of-life support expectations—(1) confident that family would provide support, (2) confident that family would not provide support, and (3) confident that friends would provide support—were strongly patterned by relationship type. When asked whether there was anyone they could count on for support besides their spouse, most respondents discussed their extended families, including their siblings and their parents, with the majority of lesbian and heterosexual respondents and about one third of respondents in gay couples indicating that their extended families would be helpful. For heterosexual couples, this support was largely assumed. Bruce (married to Penny) said,

I think in the world of serious illnesses, we kind of feel like we have fairly good support structure in place … and I don’t think we’ve ever had those conversations. I don’t think we’ve ever really thought through, it’s just kind of been assumed, that’s a terrible way of saying it but I think that if something ever seriously happened we’d be able to fall back on our parents.

Additionally, most heterosexual couples expected end-of-life support to come from their children. Eighty percent of heterosexual couples in our sample had children compared to about 25% of gay and lesbian couples. Dean (married to Cindy) said, “I haven’t been faced with it, so I would have to assume what I would do. I mean I would assume, I have children, and we still have mothers available to us.” The same-sex couples primarily discussed the importance of their parents and siblings. Colleen (married to Monica) said, “I cannot imagine a circumstance where if something serious was going on, that my mother would not be here literally as fast as she could get here and possibly bullying people on the way.” Even if gay and lesbian couples did not have children of their own, several referenced that they would rely on nieces and nephews to support them if in need. Kathy (married to Melissa) said of her wife and the support they would expect, “She comes from a family of six so she’s got three sisters and two brothers and they’ve got some children on that side so we joke with the kids and tell them they would be the ones taking care of us.”

Yet one fourth of respondents in gay and lesbian couples and one respondent in a heterosexual couple said that their families would definitely not provide support. Joe (married to Kevin) said, “I can’t picture his parents being really in a caretaking role like flying up here and taking care of him.” Rhonda (married to Sheila) also did not anticipate their families being helpful, saying, “I wouldn’t expect my brother to come out of the woodworks. He doesn’t know what’s going on with me. … I have some distant cousins in Texas somewhere, but there’s not a real connection.”

The majority of respondents in same-sex couples who mentioned not having family support said this was not a concern because of anticipated support from friends. Support from friends was not mentioned by respondents in heterosexual couples. William (married to Richard) said, “I’d say there are really good friends here, people we’ve known for years that would pitch in. … They’re like extended family.” Similarly, Pam (married to Lori) said, “I think we have a good group of people that would step in and help out. … I don’t think it would be family.” Many gay and lesbian respondents explicitly discussed their plans to rely on friends for support. Craig (married to Todd) said this was a regular discussion and they would ask each other, “Where would you rank our friends in order of who you could count on for what and where would you turn?” concluding, “I think both of us have a network of friends we could rely on at varying levels and for varying things.” Phillip (married to Mark) said that a key part of their end-of-life plans involved building a support community with friends:

We actually seriously talked with a bunch of other friends that we would all buy a big place at one point, because we’re like, okay at least, at least one of us is going to have enough money to do that, and then we’ll hire people to take care of us and we’ll grow old together? So yeah, we’re really into, like, community of friends and stuff, people taking care of each other.

For gay and lesbian couples without children, this anticipated support from friends was in part a response to not having children. Melissa (married to Linda) said of the friends they plan to rely on for later-life caregiving, “We had to build that network because we’re it. We don’t have kids to be there for us.” And some respondents in gay and lesbian marriages indicated that they would draw on both family and friend support. For example, when Sally (married to Heidi) was asked whom she could rely on for end-of-life support, she said,

My older brother is very, very supportive. I have a couple of close friends that are very supportive. I have a cousin, a lot of very close people are out of town, out of state. But I have a lot of people that I can call that have been a very big support to me.

This extensive network described by Sally and many other respondents in gay and lesbian relationships was in sharp contrast to the support networks described by the majority of respondents in heterosexual relationships who discussed only family members.

DISCUSION

In this study, we consider two key components of end-of-life planning among gay, lesbian, and heterosexual spouses: informal conversations about expectations for end of life and formal end-of-life protections. Understanding how midlife gay and lesbian spouses plan for the end of life, including future care, is important because of significant health disparities for sexual-minority compared to heterosexual populations (Institute of Medicine 2011; Riggle and Rostosky 2005; Thomeer 2013). Research suggests that gay and lesbian couples experience health disadvantages compared to their heterosexual counterparts, largely due to minority stress and discrimination at both the individual and the couple level (LeBlanc, Frost, and Wight 2015; Rostosky et al. 2016). The present study reveals how the weaker institutionalization of same-sex marriage and greater concerns about sexual-minority discrimination motivated gay and lesbian couples to be better prepared than heterosexual couples for the end of life.

Our findings suggest that gay and lesbian couples have more extensive and frequent informal discussions about future plans—related to both end-of-life and care expectations—and are more likely to create formal end-of-life protections (e.g., advanced directives) than heterosexual couples. The gay and lesbian couples in our sample engaged in more detailed planning because of an absence of legal and structural protections early in their relationship and greater concerns over family interference and lack of family support even after they were legally married. Thus, the greater engagement in end-of-life planning among gay and lesbian couples seems largely motivated by the weaker institutionalization of same-sex marriage as well as concerns about discrimination. The present findings point to gaps in end-of-life planning that are unique to heterosexual couples, perhaps resulting from assumptions built on heterosexual marital privilege. These gaps in planning may put heterosexual couples at risk of being poorly prepared for the end of life. These findings may not have emerged in prior studies because they are apparent only in contrast with gay and lesbian spouses. We highlight key themes related to institutional aspects of marriage and expectations of discrimination that contribute to differences in how gay, lesbian, and heterosexual spouses approach end-of-life planning.

Gay and Lesbian Couples

Two themes emerged as motivation for same-sex couples to engage in informal and formal end-of-life planning: weaker institutional structures and concerns of family interference and lack of family support. First, we find that a lack of legal support motivated same-sex couples to create end-of-life plans. On average, the same-sex couples in our sample spent about 13 years together before having the opportunity to marry in Massachusetts, meaning most of their relationship was spent outside of the institution of marriage (Umberson et al. 2016). This suggests that, for over a decade, these couples operated outside formal protections and with uncertainty about whether marriage rights would ever be extended to them (Chambers 1996; Lannutti 2011). As examples, one lesbian couple noted that the minister for their commitment ceremony encouraged them to create formal end-of-life documents, while another couple noted that concerns over lack of legal documentation was a major motivation for marriage. However, even after marrying in Massachusetts, there was no federal protection of same-sex marriage at the time of our study, and most states did not recognize same-sex marriages. This unique institutional context is reflected in our finding that the gay and lesbian couples in our sample were largely unsure about whether their union would be legally recognized if dealing with end-of-life issues outside of Massachusetts. Further, perhaps also reflecting this idea that gay and lesbian adults’ relationships are less institutionalized and thus less dictated by traditional marriage norms, including assumptions of end-of-life care from spouses (Hull 2006; Reczek, Elliott, and Umberson 2009), gay and lesbian couples had multiple detailed conversations about end-of-life expectations, which functioned to communicate their wishes and to reassure each other about future care.

Additionally, we find that a second key motivator for informal and formal planning for gay and lesbian couples was concerns about family interference and concerns about a lack of support from extended family. As found in other studies, gay and lesbian couples often perceived their relationships with extended family as strained and often felt their extended family did not view their relationship as legitimate (Moore and Stambolis-Ruhstorfer 2013; Powell et al. 2010; Reczek 2014). In our analysis, lesbian couples more commonly expressed concern about family interference than gay or heterosexual couples. This finding is in line with evidence that, compared to men, women have more contact with extended family and in-laws (i.e., kinship work; Di Leonardo 1987; Reczek and Umberson 2016). Thus, women may be more aware of and sensitive to family conflict and the potential for family interference than are men. This seems to be especially true for women in lesbian relationships compared to women in heterosexual relationships, perhaps because of greater family conflict between sexual minorities and extended family or sexist dynamics in which extended families are less likely to interfere with male relatives (Moore and Stambolis-Ruhstorfer 2013; Powell et al. 2010; Reczek 2014, 2015).

In part as a response to strained family-of-origin relationships and being less likely to have adult children, gay and lesbian couples referenced building strong friendship networks and having explicit conversations with those friends about providing future care (Weston 1991). Due to the support of their alternative “family” as well as extensive formal and informal end-of-life planning within the couple, these couples were not actively concerned about a potential lack of family support at the time of the interview (Dewaele et al. 2011; LeBlanc, Frost, Alston-Stepnitz et al. 2015). Future studies should consider how gay and lesbian couples draw on friendship networks for end-of-life care if marginalized by extended family. This source of support is even more notable given that heterosexual spouses actually lose friends and have a diminished social network to rely on after marriage, a dynamic that earns the term “greedy marriage” (Coser 1974; Gerstel and Sarkisian 2006).

Heterosexual Couples

We also found that stronger institutionalization of marriage—especially as related to legal structures—expectations for family and spousal support (including expecting no family interference) served as disincentives for end-of-life planning among heterosexual couples. The heterosexual couples in this study do not have the same legal or familial concerns as gay and lesbian couples, reflecting heteronormative social contexts that privilege heterosexuality. For heterosexual couples in our study, marriage is an impermeable institution that holds the assumptions and expectations that (1) healthcare organizations and legal structures will respect the wishes of the spouse, (2) extended family will not interfere in end-of-life decisions by the spouse, and (3) spouses will care for each other at the end of life with help from extended family and children. These assumptions and expectations are not necessarily accurate, but they do inform whether or how end-of-life planning occurs. Media coverage of high-profile end-of-life disputes, such as the Terri Schiavo case (Perry, Churchill, and Kirshner 2005), alongside gerontological research about family interference at the end of life (Kramer, Boelk, and Auer 2006), suggests that disputes with extended family also occur in heterosexual couples. Yet heterosexual couples in our study were largely unconcerned, indicating that they may be largely unprepared if they do encounter family interference in the future.

Regarding future support expectations from spouses and extended family, most heterosexual spouses in our study had no doubt that their spouse and their families would provide care at the end of life and in the event of serious illness—and provide care in a way that was in accordance with their wishes—even if they had never discussed their expectations with their spouse or family members. Studies of heterosexual spouses find that spouses often incorrectly assume they know each other’s end-of-life wishes, particularly if they have never explicitly discussed them (Moorman and Carr 2008; Moorman and Inoue 2013). Heterosexual couples are also much more likely to have adult children in their family networks and to assume that these adult children will be a key source of caregiving (Carr and Khodyakov 2007; Pinquart and Sörensen 2011), even though almost none had explicitly had these conversations with their children. Heterosexual couples’ expectations extended beyond their children and spouses; several heterosexual couples expressed that they would be able to rely on their parents for support even though many of their parents were already in their 70s and 80s, providing further evidence that their caregiving and end-of-life plans may not be carefully thought through.

Limitations

A qualitative dyadic approach to examining end-of-life planning across gay, lesbian, and heterosexual relationships offers unique contributions and insights, but several limitations should be addressed. First, the sample included only those couples who were together for at least seven years and were married at the time of the interview. Therefore, cohabiting couples as well as couples who broke up in the first seven years of their relationship—perhaps due to serious illness, conflict with family, legal obstacles, or even conflict around end-of-life planning—were not included in our sample. Second, our sample was fairly homogenous in terms of race-ethnicity, geography, relationship status, and social class; future studies should consider whether these same dynamics are seen among other groups of married couples or whether these dynamics differ across social stratums. Third, beyond the differences identified in our analysis, there were other important compositional differences between the gay, lesbian, and heterosexual couples that may have shaped our analysis. For example, very few of the gay and lesbian couples had children, whereas most heterosexual couples did, and the presence of children likely shaped end-of-life planning as well as family relationships.

CONCLUSION

An examination of formal and informal end-of-life planning dynamics among gay, lesbian, and heterosexual couples raises significant policy issues. Midlife heterosexual married couples seem largely unprepared for the end of life, in part because of a strong reliance on taken-for-granted norms around spousal and family roles and trust in the legal protections that accompany marriage. In this way, the current structure of legal (heterosexual) marriage serves as a disincentive to plan for later-life care and end of life. Yet, as studies repeatedly show, heterosexual married couples often do not know each other’s wishes, do not always provide care for each other or receive adequate care from children and extended family, and sometimes face interference from families (Kramer et al. 2006; Moorman and Carr 2008). The institutional aspects of heterosexual marriage and lack of concern about discrimination may actually position heterosexual couples to be poorly prepared for the end of life, at least compared to gay and lesbian couples. Thus, policy makers should consider how to incentivize end-of-life planning for all couples, taking into account current legal and societal structures and understanding that heterosexual marriage itself may serve as a disincentive.

This study also introduces two key questions for policy and future research. First, given the rapidly shifting landscape of marriage and healthcare laws, increased attention to end-of-life planning and quality of end-of-life experiences, and increased longevity in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, how will planning change for married couples over the next few decades? It may be that all couples will increase end-of-life discussions and formal planning in response to “death quality” movements and the general aging of the population (Anderson and Hussey 2000; Carlson, Morrison, and Bradley 2008). It is unclear whether this will be true for midlife adults, the focus of this study, or will impact only older adults who are more concerned about their impending mortality.

Alternatively, going forward, same-sex couples may have fewer end-of-life discussions and formal measures in the new legal landscape, as they may feel increased protection from the 2015 Supreme Court ruling expanding the right to same-sex marriage across the United States (Obergefell v. Hodges 2015). It may be that the stronger commitments to discussing end of life that we found among same-sex couples in our study will dissipate over the next few years as same-sex marriage becomes more common and institutionalized and as new cohorts of same-sex couples spend more of their relationship in legal marriage. We found evidence for this in our analysis regarding formal protections, as several gay and lesbian couples said they no longer worried about updating their formal documents after becoming legally married in Massachusetts. At the same time, in our analysis, same-sex couples seemed committed to informal planning, perhaps because they still hold many concerns about discrimination from families and organizations due to their liminal legal status. Recent initiatives in various states, such as Florida’s proposed bill that would allow hospices to refuse to serve lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adults (Florida House of Representatives 2016), indicate that the end of life may actually be a time of heightened discrimination for gay and lesbian couples.

Second, how do these end-of-life discussions and formal protections translate into actual end-of-life quality? Is it the case that gay and lesbian couples have a “better death” because of their greater planning? As suggested by the minority stress framework (Frost, Lehavot, and Meyer 2015; Meyer 2003) and the weaker institutionalization of same-sex marriage, it is likely that gay and lesbian couples—even married and with end-of-life legal measures in place—will face more discrimination and less support from family members and perhaps even medical professionals at the end of life (LeBlanc, Frost, and Wight 2015; Rostosky et al. 2016). Thus, we suggest that it is premature to assert that gay and lesbian couples will have “better deaths” than heterosexual couples even though gay and lesbian couples seem better prepared. Indeed, their greater planning for end of life may reflect valid concerns about the need for more protection. Future studies should continue to consider how death quality and planning vary for same-sex and different-sex couples as this is an important step in moving toward more equality at the end of life, for the benefit of both the dying and the bereaved.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants of the 2016 Austin Summit for their feedback on this project.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported, in part, by an Investigator in Health Policy Research Award to Debra Umberson from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; grant R21AG044585 from the National Institute on Aging (PI: Debra Umberson); grant P2CHD042849 awarded to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; and grant T32 HD007081, Training Program in Population Studies, awarded to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Biographies

Mieke Beth Thomeer is an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Her research interests include aging, family, health, gender, and sexuality. She addresses questions about how relationships influence and are influenced by physical and mental health, with particular attention to gender and sexuality. She uses both qualitative and quantitative methods, with special emphasis on dyadic methods. In her current research, she focuses on caregiving within couples in which both spouses have functional limitations.

Rachel Donnelly is a doctoral student in the Department of Sociology and the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. Her research focuses on population health, aging, and family. Her research primarily draws on dyadic and diary data to address questions about how the familial context contributes to patterns of health disparities, with attention to life course change and variations across demographic groups.

Corinne Reczek is an associate professor of sociology and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies and a faculty affiliate at the Institute for Population Research at The Ohio State University. She uses multi-methods to explore how gender, sexuality, and aging processes within family ties promote and deter health. Her current research explores how family matters for health and health behavior for adults and children in same-sex and different-sex families. She also publishes on the content and consequences of intergenerational relationships for the wellbeing of both generations across the life course.

Debra Umberson is a sociology professor and director of the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. Her research focuses on structural determinants of health across the life course. Her recent work considers how spouses influence each other’s health-related behavior, mental health, and healthcare and how these processes may vary across gay, lesbian, and heterosexual unions. In her current research, she focuses on black/white differences in exposure to the death of family members across the life course and implications for longterm health and mortality disparities.

References

- Anderson Gerard F, Hussey Peter Sotir. Population Aging: A Comparison among Industrialized Countries. Health Affairs. 2000;19(3):191–203. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.3.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam Kimberly F, Beauchaine Theodore P, Rothblum Esther D, Solomon Sondra E. Three-year Follow-up of Same-sex Couples Who Had Civil Unions in Vermont, Same-sex Couples Not in Civil Unions, and Heterosexual Married Couples. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(1):102–16. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff Kara E, Sudore Rebecca, Miao Yinghui, Boscardin Walter John, Smith Alexander K. Advance Care Planning and the Quality of End-of-life Care in Older Adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2013;61(2):209–14. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson Melissa DA, Sean Morrison R, Bradley Elizabeth H. Improving Access to Hospice Care: Informing the Debate. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2008;11(3):438–43. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr Deborah, Khodyakov Dmitry. Health Care Proxies: Whom Do Young Old Adults Choose and Why? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2007;48(2):180–94. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers David L. What If? The Legal Consequences of Marriage and the Legal Needs of Lesbian and Gay Male Couples. Michigan Law Review. 1996;95(2):447–91. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz Kathy. Constructing Grounded Theory. Los Angeles: Sage; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin Andrew J. Remarriage as an Incomplete Institution. American Journal of Sociology. 1978;84(3):634–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin Andrew J. The Deinstitutionalization of American Marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66(4):848–61. [Google Scholar]

- Coser Lewis A. Greedy Institutions: Patterns of Undivided Commitment. New York: Free Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Dewaele Alexis, Cox Nele, Van den Berghe Wim, Vincke John. Families of Choice? Exploring the Supportive Networks of Lesbians, Gay Men, and Bisexuals. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2011;41(2):312–31. [Google Scholar]

- Di Leonardo Micaela. The Female World of Cards and Holidays: Women, Families, and the Work of Kinship. Signs. 1987;12(3):440–53. [Google Scholar]

- Florida House of Representatives. HB 401, regular session 2016. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Frost David M, Lehavot Keren, Meyer Ilan H. Minority Stress and Physical Health among Sexual Minority Individuals. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2015;38(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9523-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner Daniel S, Kramer Betty J. End-of-life Concerns and Care Preferences: Congruence among Terminally Ill Elders and Their Family Caregivers. OMEGA: Journal of Death and Dying. 2010;60(3):273–97. doi: 10.2190/om.60.3.e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates Gary J. LGB Families and Relationships: Analyses of the 2013 National Health Interview Survey. Los Angeles: Williams Institute; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gerstel Naomi, Sarkisian Natalia. Marriage: The Good, the Bad, and the Greedy. Contexts. 2006;5(4):16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Harding Richard, Epiphaniou Eleni, Chidgey-Clark Jayne. Needs, Experiences, and Preferences of Sexual Minorities for End-of-life Care and Palliative Care: A Systematic Review. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2012;15(5):602–11. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hash Kristina M, Ellen Netting F. Long-term Planning and Decision-making among Midlife and Older Gay Men and Lesbians. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life & Palliative Care. 2007;3(2):59–77. doi: 10.1300/J457v03n02_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull Kathleen E. Same-sex Marriage: The Cultural Politics of Love and Law. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences near the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer Betty J, Boelk Amy Z, Auer Casey. Family Conflict at the End of Life: Lessons Learned in a Model Program for Vulnerable Older Adults. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2006;9(3):791–801. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lannutti Pamela J. For Better or Worse: Exploring the Meanings of Same-sex Marriage within the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgendered Community. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2005;22(1):5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lannutti Pamela J. Security, Recognition, and Misgivings: Exploring Older Same-sex Couples’ Experiences of Legally Recognized Same-sex Marriage. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2011;28(1):64–82. [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc Allen J, Frost David M, Alston-Stepnitz Eli, Bauermeister Jose, Stephenson Rob, Woodyatt Cory R, de Vries Brian. Similar Others in Same-sex Couples’ Social Networks. Journal of Homosexuality. 2015;62(11):1599–610. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2015.1073046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc Allen J, Frost David M, Wight Richard G. Minority Stress and Stress Proliferation among Same-sex and Other Marginalized Couples. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2015;77(1):40–59. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer Ilan H. Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(5):674–97. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles Matthew B, Michael Huberman A. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Moore Mignon R, Stambolis-Ruhstorfer Michael. LGBT Sexuality and Families at the Start of the Twenty-first Century. Annual Review of Sociology. 2013;39:491–507. [Google Scholar]

- Moorman Sara M, Carr Deborah. Spouses’ Effectiveness as End-of-life Health Care Surrogates: Accuracy, Uncertainty, and Errors of Overtreatment or Undertreatment. Gerontologist. 2008;48(6):811–19. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.6.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorman Sara M, Hauser Robert M, Carr Deborah. Do Older Adults Know Their Spouses’ End-of-life Treatment Preferences? Research on Aging. 2009;31(4):463–91. doi: 10.1177/0164027509333683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorman Sara M, Inoue Megumi. Predicting a Partner’s End-of-life Preferences, or Substituting One’s Own? Journal of Marriage and Family. 2013;75(3):734–45. [Google Scholar]

- Moorman Sara M, Carr Deborah, Boerner Kathrin. The Role of Relationship Biography in Advance Care Planning. Journal of Aging and Health. 2014;26(6):969–92. doi: 10.1177/0898264314534895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. 2015.

- Perkins Henry S, Cortez Josie D, Hazuda Helen P. Advance Care Planning: Does Patient Gender Make a Difference? American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 2004;327(1):25–32. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200401000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry Joshua E, Churchill Larry R, Kirshner Howard S. The Terri Schiavo Case: Legal, Ethical, and Medical Perspectives. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2005;143(10):744–48. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-10-200511150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart Martin, Sörensen Silvia. Spouses, Adult Children, and Children-in-law as Caregivers of Older Adults: A Meta-analytic Comparison. Psychology and Aging. 2011;26(1):1–14. doi: 10.1037/a0021863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell Brian, Blozendahl Catherine, Geist Claudia, Steelman Lala Carr. Counted Out: Same-sex Relations and Americans’ Definitions of Family: Same-sex Relations and Americans’ Definitions of Family. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rao Jaya K, Anderson Lynda A, Lin Feng-Chang, Laux Jeffrey P. Completion of Advance Directives among US Consumers. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014;46(1):65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings Deborah Ann. End-of-life Care Considerations for Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Individuals. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2012;18(1):29–34. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2012.18.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reczek Corinne. The Intergenerational Relationships of Gay Men and Lesbian Women. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2014;69(6):909–19. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reczek Corinne. Parental Disapproval and Gay and Lesbian Relationship Quality. Journal of Family Issues. 2015;37(15):2189–212. [Google Scholar]

- Reczek Corinne, Umberson Debra. Greedy Spouse, Needy Parent: The Marital Dynamics of Gay, Lesbian, and Heterosexual Intergenerational Caregivers. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2016;78(4):957–74. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reczek Corinne, Elliott Sinikka, Umberson Debra. Union Formation among Long-term Same-sex Couples. Journal of Family Issues. 2009;30(6):738–56. doi: 10.1177/0192513X09331574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggle Ellen DB, Rostosky Sharon Scales. For Better or for Worse: Psycholegal Soft Spots and Advance Planning for Same-sex Couples. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2005;36(1):90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Riggle Ellen DB, Rostosky Sharon S, Prather Robert A. Advance Planning by Same-sex Couples. Journal of Family Issues. 2006;27(6):758–76. [Google Scholar]

- Rostosky Sharon Scales, Riggle Ellen DB, Rothblum Esther D, Balsam Kimberly F. Same-sex Couples’ Decisions and Experiences of Marriage in the Context of Minority Stress: Interviews from a Population-based Longitudinal Study. Journal of Homosexuality. 2016;63(8):1019–40. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2016.1191232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostosky Sharon Scales, Korfhage Bethe A, Duhigg Julie M, Stern Amanda J, Bennett Laura, Riggle Ellen DB. Same-sex Couple Perceptions of Family Support: A Consensual Qualitative Study. Family Process. 2004;43(1):43–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2004.04301005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman David. Interpreting Qualitative Data: Methods for Analyzing Talk, Text and Interaction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Song Mi-Kyung, Kirchhoff Karin T, Douglas Jeffrey, Ward Sandra, Hammes Bernard. A Randomized, Controlled Trial to Improve Advance Care Planning among Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery. Medical Care. 2005;43(10):1049–53. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000178192.10283.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudore Rebecca L, Fried Terri R. Redefining the “Planning” in Advance Care Planning: Preparing for End-of-life Decision Making. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2010;153(4):256–61. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-153-4-201008170-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomeer Mieke Beth. Sexual Minority Status and Self-rated Health: The Importance of Socioeconomic Status, Age, and Sex. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(5):881–88. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomeer Mieke Beth, Short Lynnette. Marriage. In: Bornstein MH, Arterberry ME, Fingerman KL, Lansford JE, editors. The Sage Encyclopedia of Lifespan Human Development. New York: Sage; Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson Debra, Thomeer Mieke Beth, Kroeger Rhiannon A, Lodge Amy C, Xu Minle. Challenges and Opportunities for Research on Same-sex Relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2015;77(1):96–111. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson Debra, Thomeer Mieke Beth, Reczek Corinne, Donnelly Rachel. Physical Illness in Gay, Lesbian, and Heterosexual Marriages: Gendered Dyadic Experiences. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2016;57(4):517–31. doi: 10.1177/0022146516671570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States v. Windsor, 570 U.S. 2013.

- Weston Kath. Families We Choose: Lesbians, Gays, Kinship. New York: Columbia University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]