Abstract

Background

Reduction in 30-day readmission rate after chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)-related hospitalization is a national objective. However, little is known about trends in readmission rates in recent years, particularly in priority populations defined by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)(e.g., the elderly, women, racial/ethnic minorities, low-income and rural populations, and populations with chronic illnesses).

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from the State Inpatient Database of eight geographically-dispersed US states (Arkansas, California, Florida, Iowa, Nebraska, New York, Utah, and Washington) from 2006 through 2012. We identified all COPD-related hospitalizations by patients ≥40 years old. The primary outcome was any-cause readmission within 30 days of discharge from the index hospitalization for COPD.

Results

From 2006 to 2012, a total of 845,465 hospitalizations at risk for 30-day readmissions were identified. Overall, 30-day readmission rate for COPD-related hospitalization decreased modestly from 20.0% in 2006 to 19.2% in 2012, an 0.8% absolute decrease (OR 0.991, 95%CI 0.989–0.995, Ptrend<0.001). This modest decline remained statistically significant after adjusting for patient demographics and comorbidities (adjusted OR 0.981, 95%CI 0.977–0.984, Ptrend<0.001). Similar to the overall population, the readmission rate over the 7-year period remained persistently high in most of AHRQ-defined priority populations.

Conclusions

Our observations provide a benchmark for future investigation of the impact of Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program on readmissions after COPD hospitalization. Our findings encourage researchers and policymakers to develop effective strategies aimed at reducing readmissions among patients with COPD in an already-stressed healthcare system.

Keywords: COPD, Readmission, Epidemiology

1. Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) affects 12 million Americans and is the third leading cause of death in the US [1,2]. Approximately 700,000 patients are hospitalized for COPD in the US each year [3]. with $32 billion in direct costs incurred in 2010 alone [4]. In addition, as readmissions are costly events, 30-day readmission rates after COPD hospitalization are of great interest to a variety of stakeholders [5,6]. In this context, reduction of readmission rates in this population is an important part of national quality improvement efforts to advance health care quality and save billions of dollars on inpatient stays [7–9].

To address the substantial burden of readmission, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) developed the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP). Since October 2012, the start of fiscal year 2013, the program has penalized hospitals with higher-than-expected 30-day readmission rates for three targeted conditions (acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia). Beginning in fiscal year 2015, the list expanded to include COPD, as well as total hip and knee arthroplasty. Recently, an analysis of the Medicare beneficiaries reported an approximately 4% absolute decline in 30-day readmission rates for the three targeted conditions between 2010 and 2012 — coincident with the enactment of the ACA [9]; however, the report lacked COPD-related readmissions, a targeted condition for readmission reduction as identified by HRRP. Moreover, while the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has defined several priority populations (e.g., the elderly, women, racial/ethnic minorities, low-income and rural populations, populations with chronic illness) for which evidence-based improvements in healthcare quality and effectiveness are needed [10]. there is a dearth of research on COPD readmissions in these populations.

To address these knowledge gaps, we analyzed large, population-based, multi-payer databases from eight geographically-diverse US states to examine trends in 30-day readmission rates in patients hospitalized for COPD during 2006–2012 including those in the AHRQ-defined priority populations.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and setting

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from the State Inpatient Database (SID) of eight US states (Arkansas, California, Florida, Iowa, Nebraska, New York, Utah, and Washington) from 2006 through 2012. The SID is a component of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare and Research Quality. HCUP includes the largest collection of longitudinal hospital care data in the US with all-payer, encounter-level information. The SID captures all inpatient discharges from short-term, acute-care, nonfederal, general, and other specialty hospitals. Additional details of the SID may be found elsewhere [11]. These eight states were selected for their geographic distribution, high data quality, and chiefly because their databases contain unique patient identifiers that enable follow-up of individual patients across years. The study period was chosen based on the availability of databases across these eight states. The institutional review board of Massachusetts General Hospital approved this study (2013P002545).

2.2. Study population

Based on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) publicly reported readmission measures, we identified all hospitalizations made by patients >40 years old with a primary discharge diagnosis of COPD (ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes: 491.21, 491.22, 491.8, 491.9, 492.8, 493.20, 493.21, 493.22, and 496), or those with a primary diagnosis of respiratory failure (ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes: 518.81, 518.82, 518.84, and 799.1) and a secondary diagnosis of COPD (e-Table 1) [12]. We excluded hospitalizations by patients who left the hospital against medical advice, died in-hospital at the index hospitalization, transferred to another acute-care facility, and out-of-state residents. Based on the HCUP recommendation [13], hospitalizations in December were also excluded as they could not be followed for 30 days. As the data from Florida and Washington did not have information on discharge month, we excluded hospitalizations that occurred in the last quarter of each year for these two states.

2.3. Measurements

The SID includes information on patient demographics (age, sex, and race/ethnicity), primary insurance, estimated household income, urban-rural status, ICD-9-CM diagnoses, patient comorbidities, and disposition. The cut-offs for the quartile designation were determined using ZIP code-demographic data. Urbanerural status of the patient residence was defined according to the National Center for Health Statistics guidelines [14,15]. To adjust for potential confounding by patient-mix, Elixhauser comorbidity measures [16] were derived from the ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes in any previous hospitalizations within one year prior to the index hospitalization or during the index hospitalization.

2.4. Outcome measure

Consistent with CMS policy [12] and previous research on other diseases [17–19], the primary outcome was readmission attributable to any cause within 30 days of discharge from the index hospitalization for COPD. For the current analysis, we considered only the first readmission within 30 days. Additional readmissions within a 30-day period were not counted as an index hospitalization while subsequent admissions occurring after 30 days of the initial discharge were counted as another index hospitalization if they met the inclusion criteria. Based on CMS recommendations [20], planned (elective) readmissions were also excluded because they are not a signal of quality of care.

2.5. Statistical analysis

First, we examined patient characteristics at the index hospitalization for COPD. Next, to investigate trends in 30-day readmission rate after COPD-related hospitalization, we constructed unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models with generalized estimating equations to account for within-subject repeated measurements over time, using year as a continuous variable. In the multivariable models, we adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, primary insurance, quartiles for household income, residential status, and 27 comorbidities (Elixhauser comorbidity measures excluding pulmonary disease). As discharge dispositions (e.g., transfer to chronic care facilities) were considered as a potential mediator of the association of interest (i.e., the association between year and 30-day readmission rates), this variable was not included in the models. To examine the change in readmission rates among the AHRQ-defined priority populations and other groups, we repeated the analysis with stratification by age (40–64 years and ≥65 years), sex, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanics, and others), primary payer (Medicare, Medicaid, Private, self-pay, and others), quartiles for estimated median household income, urban–rural status of the patient residence, the number of comorbidities (0–1, 2–3, and ≥4 comorbidities), and the frequency of exacerbation (non-frequent exacerbator and frequent exacerbator). We defined patients with ≥2 hospitalizations for AECOPD within 365 days before the index hospitalization as frequent exacerbators [21]. As the data from Nebraska did not have information on race/ethnicity, the missingness (5%) was dummy coded by using the missing-indicator method [22]. All analyses were performed using STATA 14.1 (StataCorp; College Station, Texas). All P-values were two-tailed, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Between 2006 and 2012, we identified 1,161,207 hospitalizations for COPD in the eight US states. The crude admission rates for COPD were 3.9% in all states, ranging from 1.8% in Utah to 4.4% in Arkansas (eTable 2). Of these, 845,465 hospitalizations were at risk for 30-day readmissions (i.e., index hospitalizations). The patient characteristics of index hospitalizations are shown in Table 1 (the full version is presented as eTable3). The mean age of patients was 69 years and 59% were female. Most patients were non-Hispanic whites (74%) and Medicare beneficiaries (70%). One-third of patients lived in areas with the lowest quartile for household income; 12% of patients lived in rural areas. Approximately 70% of patients had ≥2 comorbidities. The proportion of patients with ≥4 comorbidities increased from 21% in 2006 to 29% in 2012 (Ptrend<0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of index hospitalizations for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 2006–2012.

| Variables | Overall | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 69 (0.01) | 70 (0.04) | 69 (0.04) | 70 (0.03) | 69 (0.03) | 69 (0.03) | 69 (0.03) | 69 (0.04) |

| 40-64 years, mean (SD) | 296,057 (35) | 37,520 (34) | 36,376 (35) | 44,023 (34) | 48,315 (35) | 47,177 (35) | 48,673 (36) | 33,973 (37) |

| ≥65 years, mean (SD) | 549,408 (65) | 73,918 (66) | 69,025 (65) | 85,206 (66) | 88,557 (65) | 86,018 (65) | 87,899 (64) | 58,785 (63) |

| Female | 494,498 (59) | 65,391 (59) | 61,547 (58) | 75,533 (59) | 80,039 (59) | 77,875 (59) | 79,651 (58) | 54,462 (59) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 591,092 (70) | 76,155 (68) | 73,359 (70) | 88,231 (68) | 97,809 (71) | 93,886 (70) | 95,536 (70) | 66,116 (71) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 91,972 (11) | 11,589 (10) | 11,875 (11) | 13,679 (11) | 14,809 (11) | 14,686 (11) | 15,029 (11) | 10,305 (11) |

| Hispanics | 80,282 (10) | 10,159 (9) | 10,274 (10) | 10,836 (9) | 12,262 (9) | 13,528 (10) | 14,043 (10) | 9180 (10) |

| Primary health insurance | ||||||||

| Medicare | 593,475 (70) | 79,209 (71) | 73,427 (70) | 90,224 (70) | 95,350 (70) | 93,319 (70) | 96,239 (71) | 65,707 (71) |

| Medicaid | 102,410 (12) | 12,702 (11) | 12,388 (12) | 14,939 (12) | 16,852 (12) | 17,006 (13) | 17,385 (13) | 11,138 (12) |

| Private | 101,315 (12) | 14,004 (13) | 13,643 (13) | 16,722 (13) | 16,846 (12) | 14,975 (11) | 14,925 (11) | 10,200 (11) |

| Quartiles for median household income | ||||||||

| 1 (lowest) | 268,470 (33) | 35,182 (33) | 33,063 (32) | 40,490 (32) | 43,526 (33) | 42,950 (33) | 43,664 (33) | 29,595 (33) |

| 2 | 226,471 (28) | 29,515 (27) | 28,069 (27) | 35,038 (28) | 37,013 (28) | 35,175 (27) | 36,604 (27) | 25,057 (28) |

| 3 | 192,791 (23) | 25,443 (24) | 24,413 (24) | 29,479 (23) | 30,931 (23) | 30,342 (23) | 31,277 (23) | 20,906 (23) |

| 4 (highest) | 134,908 (16) | 18,117 (17) | 16,809 (16) | 20,752 (17) | 21,865 (16) | 21,267 (16) | 21,597 (16) | 14,501 (16) |

| Living in urban area | 742,733 (88) | 98,415 (88) | 93,447 (89) | 114,682 (89) | 119,964 (88) | 117,250 (88) | 120,339 (88) | 78,636 (85) |

| Number of comorbidities | ||||||||

| 0-1 comorbidity | 241,001 (29) | 38,325 (34) | 34,169 (32) | 38,483 (30) | 37,698 (28) | 34,475 (26) | 34,099 (25) | 23,752 (26) |

| 2-3 comorbidities | 380,766 (45) | 49,642 (45) | 47,152 (45) | 58,667 (45) | 61,850 (45) | 59,966 (45) | 61,566 (45) | 41,923 (45) |

| ≥4 comorbidities | 223,698 (26) | 23,471 (21) | 24,080 (23) | 32,079 (25) | 37,324 (27) | 38,754 (29) | 40,907 (30) | 27,083 (29) |

| Frequent exacerbator** | 79,118(11) | – | 11,357 (11) | 12,870 (10) | 14,627 (11) | 14,836 (11) | 15,082 (11) | 10,346 (11) |

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise specified.; Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; NA, data were not available.

Defined by ≥ 2 hospitalization for acute exacerbation of COPD in the past year.

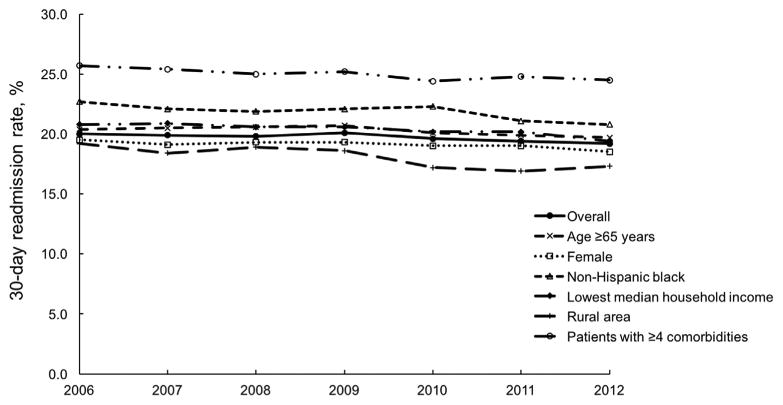

During the study period, there were a total of 166,668 readmissions within 30 days of hospitalization for COPD which yielded a crude overall readmission rate of 19.7% (95%CI, 19.6%–19.8%; eTable 4). From 2006 to 2012, there was an absolute 0.8% decrease in the overall 30-day readmission rate after hospitalization for COPD (20.0% in 2006 vs. 19.2% in 2012; Ptrend<0.001; Fig. 1 and eTable 4). The unadjusted odds ratio (OR) for changes in 30-day readmission rates per year was 0.991 (95%CI, 0.989–0.995; P < 0.001; Table 2). This statistically significant but modest decline persisted after adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, primary insurance, estimated median household income, patient residence, and 27 Elixhauser comorbidity measures (adjusted OR, 0.981; 95% CI, 0.977–0.984; P < 0.001; eTable 5). In addition, the modest decline persisted across states.

Fig. 1.

Trends in 30-day readmission rates after hospitalization for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease during 2006–2012, overall and major Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality-defined priority populations.

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted associations between calendar year and 30-day readmission rate after hospitalization for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stratified by patient characteristic.

| Stratification | Unadjusted odds ratio for change in readmission rates per year (95%CI) | P value | Adjusted odds ratio for change in readmission rates per year (95%CI)* | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 0.991 (0.989–0.995) | <0.001 | 0.981 (0.977–0.984) | <0.001 |

| Age | ||||

| 40-64 years | 0.994 (0.990–0.999) | 0.04 | 0.984 (0.979–0.989) | <0.001 |

| ≥65 years | 0.991 (0.988–0.995) | <0.001 | 0.982 (0.979–0.986) | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 0.990 (0.986–0.995) | <0.001 | 0.982 (0.78–0.987) | <0.001 |

| Female | 0.993 (0.989–0.996) | 0.003 | 0.983 (0.979–0.987) | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 0.993 (0.989–0.996) | 0.001 | 0.985 (0.982–0.989) | <0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.986 (0.978–0.994) | 0.003 | 0.978 (0.969–0.986) | <0.001 |

| Hispanics | 0.991 (0.982–0.999) | 0.04 | 0.975 (0.966–0.984) | <0.001 |

| Others | 0.986 (0.973–1.000) | 0.053 | 0.971 (0.956–0.986) | <0.001 |

| Primary health insurance | ||||

| Medicare | 0.989 (0.986–0.992) | <0.001 | 0.981 (0.977–0.984) | <0.001 |

| Medicaid | 0.991 (0.983–0.999) | 0.02 | 0.986 (0.977–0.994) | 0.001 |

| Private | 1.000 (0.991–1.010) | 0.95 | 0.988 (0.977–0.998) | 0.02 |

| Self-pay | 0.993 (0.973–1.013) | 0.49 | 1.010 (0.988–1.032) | 0.37 |

| Others | 0.997 (0.979–1.016) | 0.79 | 0.989 (0.970–1.009) | 0.29 |

| Quartiles for median household income | ||||

| 1 (lowest) | 0.988 (0.983–0.992) | <0.001 | 0.978 (0.973–0.983) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 0.987 (0.982–0.992) | <0.001 | 0.979 (0.974–0.985) | <0.001 |

| 3 | 0.994 (0.986–1.000) | 0.07 | 0.984 (0.978–0.990) | <0.001 |

| 4 (highest) | 1.006 (0.998–1.013) | 0.13 | 0.995 (0.987–1.003) | 0.20 |

| Patient residence | ||||

| Urban area | 0.995 (0.992–0.998) | 0.001 | 0.985 (0.982–0.988) | <0.001 |

| Rural area | 0.974 (0.967–0.983) | <0.001 | 0.967 (0.958–0.976) | <0.001 |

| Number of comorbidities | ||||

| 0-1 comorbidity | 0.976 (0.970–0.981) | <0.001 | 0.978 (0.972–0.984) | <0.001 |

| 2-3 comorbidities | 0.980 (0.976–0.984) | <0.001 | 0.981 (0.977–0.986) | <0.001 |

| ≥4 comorbidities | 0.990 (0.985–0.995) | <0.001 | 0.990 (0.985–0.996) | <0.001 |

| Frequency of exacerbation** | ||||

| Non-frequent exacerbator | 0.987 (0.983–0.991) | <0.001 | 0.981 (0.977–0.985) | <0.001 |

| Frequent exacerbator | 0.996 (0.987–1.005) | 0.43 | 0.992 (0.983–1.002) | 0.13 |

| Residential state | ||||

| Arkansas | 0.967 (0.955–0.979) | <0.001 | 0.960 (0.947–0.973) | <0.001 |

| California | 0.996 (0.990–1.002) | 0.24 | 0.980 (0.974–0.986) | <0.001 |

| Florida | 1.002 (0.997–1.007) | 0.37 | 0.991 (0.986–0.996) | <0.001 |

| Iowa | 0.953 (0.917–0.991) | 0.02 | 0.955 (0.918–0.994) | 0.03 |

| Nebraska | 0.970 (0.950–0.990) | 0.003 | 0.968 (0.948–0.988) | 0.002 |

| New York | 0.991 (0.986–0.996) | <0.001 | 0.979 (0.974–0.984) | <0.001 |

| Utah | 0.985 (0.955–1.016) | 0.34 | 0.971 (0.939–1.004) | 0.08 |

| Washington | 0.997 (0.984–1.010) | 0.66 | 0.990 (0.963–1.018) | 0.50 |

Adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, primary health insurance, quartiles for median household income, patient residence, and 27 Elixhauser comorbidities, with excluding the variable that was used for stratification.

Defined by = 2 hospitalization for acute exacerbation of COPD in the past year.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Table 2, eTable 4, and e-Figs. 1–8 present the 30-day readmission rates as well as unadjusted and adjusted OR for change per year after stratification by age, sex, race/ethnicity, primary payer, estimated median household income, patient residence, the number of comorbidities, and frequency of exacerbation. Similar to the overall population results, throughout the 7-year period, the 30-day readmission rate remained high in most of the AHRQ-defined priority populations – e.g., patients aged ≥65 years (from 20.4% in 2006 to 19.7% in 2012; 0.7% absolute decrease; e-Fig. 1), women (from 18.9% in 2006 to 18.2% in 2012; 0.7% absolute decrease; e-Fig. 2), non-Hispanic black (from 22.7% in 2006 to 20.8% in 2012; 1.9% absolute decrease; e-Fig. 3), and those with multiple comorbidities (e.g., among patients with 4 ≥ comorbidities: from 25.7% in 2006 to 24.5% in 2012; 1.2% absolute decrease; e-Fig. 6). Similarly, while not an AHRQ-defined priority population, 30-day readmission rates among Medicare beneficiaries remained consistently high (from 21.0% in 2006 to 20.0% in 2012; 1.0% absolute decrease; e-Fig. 7). In addition, 30-day readmission rates among the frequent exacerbator, a unique phenotype of COPD, remained consistently high (from 35.9% in 2007 to 35.3% in 2012; 0.6% decrease; e-Fig. 8).

4. Discussion

In this population-based study using data from eight geographically-diverse US states, we found that the overall 30-day readmission rates was 19.7%, with a modest decrease (0.8% absolute decrease) from 2006 to 2012. Furthermore, in the AHRQ-defined priority populations (e.g., the elderly, women, non-Hispanic black, and patients with multiple comorbidities), the 30-day readmission rate remained persistently high throughout the 7-year period – there were no clinically-meaningful changes during the study periods in some strata, although the downward trends were statistically significant because of their large sample size. The observed 30-day readmission rate in patients hospitalized for COPD was consistent with the prior reports solely from the Medicare population (overall 30-day readmission rates, 18%–23%) [23,24]. The current study corroborates these earlier findings and extends them by demonstrating changes in 30-day readmission rates, both in the overall population and among more vulnerable groups.

As readmissions are increasingly recognized an important indicator of healthcare quality and as costly events, 30-day readmission rates are of great interest to a variety of stakeholders [5,6]. Recently, Zuckerman et al. analyzed Medicare data, and found an approximately 4% absolute decrease in 30-day readmission rates for patients hospitalized for the three initially targeted conditions identified by the HRRP program (i.e., acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia) from 2007 to 2012. The study reported a significant decline between April 2010 and September 2012, the period after the enactment of the ACA (March 2010) [9]. In addition, from 2007 to 2012, there was an approximately 2% decline in the 30-day readmission rate after hospitalization for non-targeted conditions; however, this prior study excluded patients hospitalized with COPD from their analysis [9]. In contrast to these findings, in our analysis of population-based data of patients hospitalized for COPD from 2006 to 2012, the decrease in 30-day readmission rate was smaller, not only in the overall population (0.8% decrease) but also in our Medicare population (1.0% decrease). Reasons for the apparent discrepancy of the 30-day readmission rates between these disease conditions are likely multifactorial as hospital readmission is a complex construct involving patients' baseline health conditions, inpatient care, outpatient management, and the post-discharge environment. Possible explanations for the persistently high 30-day readmission rates in COPD patients include the higher proportion of patients with comorbidities [25,26], suboptimal inpatient care (e.g., only one in three COPD hospitalizations provide patients with the guideline-recommended treatments) [27] and suboptimal outpatient management [28,29] or access to care, including pulmonary rehabilitation [30]. In conjunction with prior data, our observation – the persistently high 30-day readmission rates in patients hospitalized for COPD – presents a major opportunity to advance quality of care and improve patient outcomes. Although the analyzed datasets precluded examination of the effect of HRRP on patients hospitalized for COPD (since COPD was added to the HRRP in fiscal year 2015), our findings will serve as an important foundation for further investigation to determine the national impact of the expanded HRRP program.

COPD-related healthcare utilization in the AHRQ-defined priority populations – groups with unique healthcare needs that require special focus [10] – is an increasingly important topic [31–33]. For example, data from a single managed care organization in Northern California demonstrated that COPD exacerbations disproportionately affect racial/ethnic minorities (e.g., non-Hispanic black) and individuals with lower economic status [31]. These findings were mirrored by a single-year analysis in 2008 across a selection of 15 states that reported disparities in 30-day readmission rates after hospitalization for COPD [34]. Consistent with these studies, our analysis demonstrated a persistently high 30-day readmission rate in the AHRQ-defined priority populations over the 7-year period. The mechanism linking these population characteristics to the high 30-day readmission rates are unclear and likely multifactorial, such as higher chronic disease severity [35]. Greater degree of past and current smoking [36]. Suboptimal living conditions [37], limited adherence to disease management programs and self-management education [38], and poorer access to prevention-oriented outpatient management [39] for some population groups. Further research is warranted to better understand the underlying reasons for the persistently high readmission rates particularly in these priority populations [32].

Our study has several potential limitations. First, the analysis was based on the administrative data; thus, misclassification of hospitalizations is possible. In addition, there might be a potential bias due to changes in coding practice over time. Nevertheless, the HCUP data are thought to be accurate, are rigorously tested, and widely used to estimate diagnoses and hospitalization frequency [40,41]. Additionally, data collection errors of the SID should not vary significantly between study years and therefore, any potential errors are unlikely to have affected the trend analysis. Second, the use of a 30-day interval is not supported by biological evidence and is, therefore, somewhat arbitrary. Since evidence that indicates a definitive time-window for readmission analyses is currently lacking in COPD patients, we used the 30-day interval set by the CMS [42,43]. Third, due to lack of out-of-hospital mortality data in the SID, we were unable to account for the competing risk of mortality on readmissions. However, the proportion of patients with this competing risk should not have varied substantially across the study years. Fourth, as with any observational study, our study might be confounded by unmeasured factors – e.g., the severity of COPD exacerbation at the index hospitalization, inpatient acute management, outpatient chronic management, and access to ambulatory care after hospital discharge. Lastly, our data were not a random sample of all US patients with COPD, thereby the generalizability of our inference to the US population might be limited. However, the modest decline in the rates of 30-day readmission persisted across states, and the eight analyzed states are geographically-dispersed and represent approximately 30% of the US population. Moreover, our data consists of a wide range of COPD prevalence and COPD hospitalization rates from low area to high area [1,44].

5. Conclusions

By using large, all-payer, population-based data from 2006 through 2012, we found that the overall 30-day readmission rate was 19.7%. During the 7-year study period, for this overall population, readmission rates decreased modestly, from 20.0% to 19.2%, a 0.8% absolute decrease. We also found that, among the AHRQ-defined priority populations (e.g., the elderly, low-income groups, and patients with multiple comorbidities), readmission rates remained high. Compared to the previously-reported decline in the 30-day readmission rates in patients with targeted (e.g., pneumonia) and non-targeted disease conditions defined by CMS [9], the observed change in readmission rate among COPD patients was smaller. For researchers, our findings will serve as a benchmark for further investigation of the impact of 2015 HRRP implementation on readmissions in patients with COPD. The observed consistently high rates of 30-day readmission should encourage stakeholders to develop strategies aimed at reducing readmissions among patients with COPD in an already-stressed healthcare system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Funding: This study was supported by the grant R01 HS-023305 (PI, Camargo) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Rockville, MD). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Goto was supported by grants from St Luke's Life Science Institute and Uehara Kinen Memorial Foundation (Tokyo, Japan).

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- CMS

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- HCUP

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project

- HRRP

Hospital Readmissions Reduction (HRR) Program

- ICD-9-CM

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

- OR

odds ratio

- SID

State Inpatient Database

Footnotes

Author contributions: T.G. takes responsibility for the paper as a whole. T. G., M.K.F., S.T., N.A.H., C.A.C and K.H. conceived the study. S.T., N.A.H. and C.A.C. obtained research funding and supervised the conduct of the study. T.G., M.K.F., K.G., and K.H. provided statistical advice and T.G. analyzed the data. T.G. drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed substantially to its revision.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Appendix A. Supplementary data: Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2017.07.058.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among adults–United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(46):938–943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kochanek KD, Xu J, Murphy SL, Minino AM, Kung HC. Deaths: final data for 2009. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2011;60(3):1–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.HCUPnet. [Accessed November 7, 2016]; http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/HCUPnet.jsp.

- 4.Ford ES, Murphy LB, Khavjou O, Giles WH, Holt JB, Croft JB. Total and state-specific medical and absenteeism costs of COPD among adults aged >/= 18 years in the United States for 2010 and projections through 2020. Chest. 2015;147(1):31–45. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lieu TA, Au D, Krishnan JA, et al. Comparative effectiveness research in lung diseases and sleep disorders: recommendations from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(7):848–856. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201104-0634WS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krishnan JA, Lindenauer PK, Au DH, et al. Stakeholder priorities for comparative effectiveness research in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a workshop report. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(3):320–326. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201206-0994WS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma G, Kuo YF, Freeman JL, Zhang DD, Goodwin JS. Outpatient follow-up visit and 30-day emergency department visit and readmission in patients hospitalized for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(18):1664–1670. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.QualityNet. Overview: Readmission Measures. [Accessed September 2, 2016]; http://www.qualitynet.org/

- 9.Zuckerman RB, Sheingold SH, Orav EJ, Ruhter J, Epstein AM. Readmissions, observation, and the hospital readmissions reduction program. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(16):1543–1551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1513024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Priority Populations. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Accessed Sep 2, 2016]; http://www.ahrq.gov/health-care-information/priority-populations/index.html.

- 11.Overview of the State Inpatient Databases (SID) Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Accessed August 15, 2016]; http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/sidoverview.jsp.

- 12.Yale New Haven Health Services Corporation/Center for Outcomes Research & Evaluation. 2014 Measures Updates and Specifications Report Hospital-Level 30-Day Risk-Standardized Readmission Measures. [Accessed October 1, 2016];2014 http://altarum.org/sites/default/files/uploaded-publication-files/Rdmsn_Msr_Updts_HWR_0714_O.pdf.

- 13.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; [Accessed September 2, 2016]. Overview of Key Readmission Measures and Methods. Report # 2012-04. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/methods/2012_04.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Center for Health Statistics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed September 1, 2016]; http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/

- 15.HCUPnet definitions. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; [Accessed September 2, 2016]. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/HCUPnet.jsp?GoTo=HCUPnetDefinitions. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309(4):355–363. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.216476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krumholz HM, Lin Z, Drye EE, et al. An administrative claims measure suitable for profiling hospital performance based on 30-day all-cause readmission rates among patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4(2):243–252. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.957498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dreyer RP, Ranasinghe I, Wang Y, et al. Sex differences in the rate, timing, and principal diagnoses of 30-day readmissions in younger patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2015;132(3):158–166. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Measure Methodology, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Readmission Updates. [Accessed September 2, 2016]; https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualitylnits/Measure-Methodology.html.

- 21.Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, et al. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(12):1128–1138. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miettinen OS. Theoretical epidemiology: principles of occurrence research in medicine. Delmar Pub. 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh G, Zhang W, Kuo YF, Sharma G. Association of psychological disorders with 30-day readmission rates in patients with COPD. Chest. 2016;149(4):905–915. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-0449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chatila WM, Thomashow BM, Minai OA, Criner GJ, Make BJ. Comorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(4):549–555. doi: 10.1513/pats.200709-148ET. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baker CL, Zou KH, Su J. Risk assessment of readmissions following an initial COPD-related hospitalization. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2013;8:551–559. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S51507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindenauer PK, Pekow P, Gao S, Crawford AS, Gutierrez B, Benjamin EM. Quality of care for patients hospitalized for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(12):894–903. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-12-200606200-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rutschmann OT, Janssens JP, Vermeulen B, Sarasin FP. Knowledge of guidelines for the management of COPD: a survey of primary care physicians. Respir Med. 2004;98(10):932–937. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salinas GD, Williamson JC, Kalhan R, et al. Barriers to adherence to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease guidelines by primary care physicians. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2011;6:171–179. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S16396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han MK, Martinez CH, Au DH, et al. Meeting the challenge of COPD care delivery in the USA: a multiprovider perspective. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(6):473–526. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)00094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eisner MD, Blanc PD, Omachi TA, et al. Socioeconomic status, race and COPD health outcomes. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(1):26–34. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.089722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prieto-Centurion V, Gussin HA, Rolle AJ, Krishnan JA. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease readmissions at minority-serving institutions. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(6):680–684. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201307-223OT. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; [Accessed September 5, 2016]. HHS Initiative on Multiple Chronic Conditions. http://www.hhs.gov/ash/about-ash/multiple-chronic-conditions/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elixhauser A, Au DH, Podulka J. Readmissions for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, 2008: Statistical Brief #121. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs; Rockville (MD): 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Putcha N, Han MK, Martinez CH, et al. Comorbidities of COPD have a major impact on clinical outcomes, particularly in African Americans. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2014;1(1):105–114. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.1.1.2014.0112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dransfield MT, Davis JJ, Gerald LB, Bailey WC. Racial and gender differences in susceptibility to tobacco smoke among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2006;100(6):1110–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schikowski T, Sugiri D, Ranft U, et al. Long-term air pollution exposure and living close to busy roads are associated with COPD in women. Respir Res. 2005;6:152. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.George J, Kong DC, Stewart K. Adherence to disease management programs in patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2007;2(3):253–262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Croft JB, Lu H, Zhang X, Holt JB. Geographic accessibility of pulmonologists for adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: United States. Chest. 2013;2016 doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hasegawa K, Tsugawa Y, Tsai CL, Brown DF, Camargo CA., Jr Frequent utilization of the emergency department for acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res. 2014;15:40. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-15-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hasegawa K, Gibo K, Tsugawa Y, Shimada YJ, Camargo CA., Jr Age-related differences in the rate, timing, and diagnosis of 30-day readmissions in hospitalized adults with asthma exacerbation. Chest. 2016;149(4):1021–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feemster LC, Au DH. Penalizing hospitals for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease readmissions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189(6):634–639. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201308-1541PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joynt KE, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmissions–truth and consequences. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(15):1366–1369. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1201598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holt JB, Zhang X, Presley-Cantrell L, Croft JB. Geographic disparities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) hospitalization among Medicare beneficiaries in the United States. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2011;6:321–328. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S19945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.