Abstract

Background and objectives

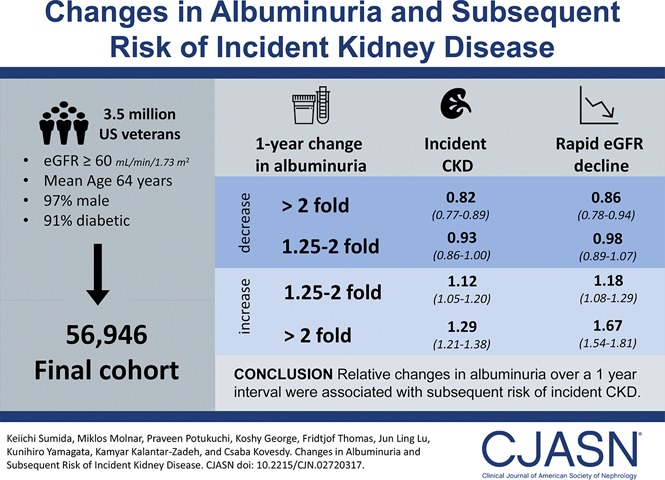

Albuminuria is a robust predictor of CKD progression. However, little is known about the associations of changes in albuminuria with the risk of kidney events outside the settings of clinical trials.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

In a nationwide cohort of 56,946 United States veterans with an eGFR≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, we examined the associations of 1-year fold changes in albuminuria with subsequent incident CKD (>25% decrease in eGFR reaching <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2) and rapid eGFR decline (eGFR slope <−5 ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year) assessed using Cox models and logistic regression, respectively, with adjustment for confounders.

Results

The mean age was 64 (SD, 10) years old; 97% were men, and 91% were diabetic. There was a nearly linear association between 1-year fold changes in albuminuria and incident CKD. The multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) of incident CKD associated with more than twofold decrease, 1.25- to twofold decrease, 1.25- to twofold increase, and more than twofold increase (versus <1.25-fold decrease to <1.25-fold increase) in albuminuria were 0.82 (95% confidence interval, 0.77 to 0.89), 0.93 (95% confidence interval, 0.86 to 1.00), 1.12 (95% confidence interval, 1.05 to 1.20), and 1.29 (95% confidence interval, 1.21 to 1.38), respectively. Qualitatively similar associations were present for rapid eGFR decline (adjusted odds ratios; 95% confidence intervals for corresponding albuminuria changes: adjusted odds ratio, 0.86; 95% confidence interval, 0.78 to 0.94; adjusted odds ratio, 0.98; 95% confidence interval, 0.89 to 1.07; adjusted odds ratio, 1.18; 95% confidence interval, 1.08 to 1.29; and adjusted odds ratio, 1.67; 95% confidence interval, 1.54 and 1.81, respectively).

Conclusions

Relative changes in albuminuria over a 1-year interval were linearly associated with subsequent risk of kidney outcomes. Additional studies are warranted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of the observed associations and test whether active interventions to lower elevated albuminuria can improve kidney outcomes.

Keywords: albuminuria; chronic kidney disease; microalbuminuria; Odds Ratio; Proportional Hazards Models; Logistic Models; glomerular filtration rate; Veterans; Renal Insufficiency, Chronic; kidney; diabetes mellitus

Introduction

Albuminuria is an established and strong prognostic factor for various adverse clinical outcomes, such as mortality, ESRD, and cardiovascular events, in the general population (1–5) and patients with diabetes, hypertension, vascular disease, and CKD (6–11). Existing clinical practice guidelines have emphasized the use of current level of albuminuria as well as eGFR for CKD definition and staging (12,13).

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in using change in albuminuria as a potential surrogate measure of CKD progression. A recent meta-analysis of clinical trials has shown that short-term treatment-induced changes in albuminuria correlate well with long-term treatment effects on ESRD, suggesting that albuminuria could be considered a therapeutic target in clinical practice and also, a surrogate end point for ESRD in clinical trials (14). However, relatively short evaluation periods (a median of 6 months) for changes in albuminuria and highly selected patients with diabetes or hypertension treated mainly with renin-angiotensin system inhibitors in previous trials limit the generalizability of these findings, and the controversy as to whether changes in albuminuria can be used as an acceptable surrogate for ESRD continues to be debated (15–18). Outside the setting of clinical trials, few observational studies have examined the associations of changes in albuminuria with kidney outcomes (19–21). Furthermore, the changes in urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) in previous studies were generally defined using a single first measurement and a single last measurement, which may be subject to potentially substantial intraindividual variability of albuminuria over time (22,23), and thus, may be less precise than alternative analytic approaches using multiple albuminuria measurements.

The objective of our study was to investigate the associations of relative changes in albuminuria over a 1-year interval as well as annual changes (slopes) in albuminuria with various kidney outcomes in individuals with normal eGFR.

Materials and Methods

Cohort Definition

Our study used data from a retrospective cohort study (the Racial and Cardiovascular Risk Anomalies in CKD Study), which included 3,582,478 United States veterans with eGFR≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 between October 1, 2004 and September 30, 2006 (baseline period) (24,25). The algorithm for cohort definition is shown in Supplemental Figure 1. In this study, we used at least two UACR measurements that were 1 year apart; therefore, patients without any UACR measurements (n=3,374,292) or those without two UACR measurements that were 1 year apart (n=150,985) during the baseline period were excluded. After further exclusion of patients with erroneous data (n=255), 56,946 patients were included in our final cohort.

Exposure Variable

The primary exposure of interest was a 1-year fold change in UACR during the 2-year baseline period. A margin of 6 months before and after the date of the last UACR measurement was allowed for determining the last available UACR to calculate the change (e.g., UACR between 0.5 and 1.5 years after the first UACR measurement could be used for the 1-year fold change) (26). We stratified 1-year fold UACR changes into five a priori categories before analyses started: more than twofold decrease, 1.25- to twofold decrease, 1.25-fold decrease to 1.25-fold increase, 1.25- to twofold increase, and more than twofold increase (20). The group with 1-year fold UACR changes of 1.25-fold decrease to 1.25-fold increase (i.e., stable UACR) was used as a reference in all categorical analyses. One-year fold UACR change was also treated as a continuous variable to examine nonlinear associations.

Covariates

Baseline variables were determined at the date of the first UACR measurement. Sociodemographic characteristics, comorbid conditions, laboratory characteristics, and medication use were obtained as previously described (27,28). Briefly, data on patients’ age, sex, race, marital status, body mass index, systolic BP, diastolic BP, comorbid conditions, medication use, mean per capita income, and service connectedness were collected from various national Veterans Affairs (VA) research data files (29). Prevalent comorbidities were defined as the presence of relevant International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification Diagnostic and Procedure Codes and Current Procedural Terminology codes recorded from October 1, 2004 to September 30, 2006 (Supplemental Table 1) (27,28). Intraindividual slopes of systolic BP and eGFR were estimated from linear mixed effects models using all of their available values from the UACR change evaluation period. The treatment status of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, or direct renin inhibitors) was defined on the basis of their use at the dates of the first and last UACR measurements and categorized into four patterns (i.e., use at both, either, or neither dates). Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors adherence was also defined as the proportion of days covered by the drug during the evaluation period for UACR change (30). In addition to the information derived from VA sources, we included select socioeconomic indicators using 2004 county typology codes (housing stress, low education, low employment, and persistent poverty) (Supplemental Table 2).

Outcome Assessment

The coprimary outcomes were incident CKD and rapid eGFR decline. Incident CKD was defined as two eGFR levels <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 separated by ≥90 days and a >25% decrease from baseline eGFR (31). The start of follow-up was the date of the last UACR measurement, and patients were censored at the time of death, the last encounter, or the last date of available kidney event (October 13, 2012 and September 13, 2011 for incident CKD and ESRD, respectively) (32). Rapid eGFR decline was defined as an eGFR slope <−5 ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year calculated from an ordinary least squares regression model using all outpatient eGFR measurements available from the cohort entry date to October 13, 2012 (a median [interquartile interval (IQI)] of ten [5 to 17] measurements). Information about all-cause mortality was obtained from the VA Vital Status Files (33).

Statistical Analyses

Baseline characteristics were summarized according to categories of UACR change and presented as a number (percentage) for categorical variables and mean±SD for continuous variables with normal distribution or median (IQI) for those with skewed distribution. Differences across categories were assessed using ANOVA and chi-squared tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. The associations of UACR changes with kidney outcomes were assessed using Cox proportional hazards models (for incident CKD) and logistic regression models (for rapid eGFR decline). For the Cox models, the proportionality assumption was tested by plotting log (−log [survival rate]) against log (survival time) and by scaled Schoenfeld residuals, which showed no violations. Models were incrementally adjusted for the following confounders on the basis of theoretical considerations: model 1 unadjusted; model 2 adjusted for age, sex, race, baseline eGFR, and log-transformed UACR; model 3 additionally accounted for prevalent comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, chronic lung disease, liver disease, dementia, rheumatic disease, malignancy, depression, and HIV/AIDS); and model 4 additionally included baseline body mass index, systolic and diastolic BP, slopes of systolic BP and eGFR calculated during the 1-year UACR change estimation period, baseline use of statins and nonopioid analgesics, renin-angiotensin system inhibitor treatment status, and renin-angiotensin system inhibitor adherence. Because we took a clinical trial approach, in which we assume that future change in UACR is a surrogate end point of incident CKD, we adjusted for baseline covariates measured at the first UACR measurement and started the follow-up at the last UACR measurement. Nonlinear associations were tested by adding the quadratic term of UACR change to the models. We further explored nonlinearity by using restricted cubic splines.

We performed several sensitivity analyses to evaluate the robustness of our main findings. The associations of UACR change with outcomes were examined in subgroups of patients stratified by baseline UACR levels and the number of UACR measurements available during the 2-year baseline period as well as various other characteristics. Potential interactions were tested by including interaction terms. Because death and incident CKD are competing events, competing risk regression models were performed. We also investigated whether accounting for socioeconomic parameters and baseline serum albumin and total cholesterol further attenuates the associations of UACR change with kidney outcomes as an additional model (model 5). Additionally, the associations were examined using UACR slopes calculated by both ordinary least squares regression models and linear mixed effects models using all intraindividual UACR values (34).

Of the variables included in multivariable-adjusted models, data points were missing for race (8%), body mass index (3%), systolic and diastolic BP (<1%), and eGFR slope (<1%). Missing values were not imputed in primary analyses but were substituted by multiple imputation procedures using the STATA mi set of command in sensitivity analyses. The reported P values are two sided and reported as significant at <0.05 for all analyses. All of the analyses were conducted using Stata/MP, version 14 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). The study was approved by the institutional review boards at the Memphis and Long Beach VA Medical Centers, with exemption from informed consent.

Results

Patients’ baseline characteristics overall and in patients stratified by 1-year fold UACR change categories are shown in Table 1. Among 56,946 patients, 9412 (17%), 8536 (15%), 16,368 (29%), 10,972 (19%), and 11,658 (20%) experienced more than twofold decrease, 1.25- to twofold decrease, stable, 1.25- to twofold increase, and more than twofold increase in UACR, respectively. Overall, the mean age at baseline was 64 (SD, 10) years old; 97% were men, and 15% were black. Also, 91% were diabetic, and 84% had a history of hypertension. The mean eGFR was 79 (SD, 16) ml/min per 1.73 m2, and the median (IQI) of UACR was 13 (6–29) mg/g at baseline. Compared with patients with stable UACR (29% of the cohort), both those with decreases in UACR (31% of the cohort) and those with increases in UACR (40% of the cohort) tended to have a poorer risk profile.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics overall and stratified by categories of 1-year fold changes in urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio among 56,946 United States veterans

| Characteristics | Total, N = 56,946 | 1-yr Fold Changes in UACR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| More than Twofold Decrease, n = 9412 | 1.25- to Twofold Decrease, n = 8536 | Stable, n = 16,368 | 1.25- to Twofold Increase, n = 10,972 | More than Twofold Increase, n = 11,658 | ||

| Age, yr | 64±10 | 63±11 | 64±10 | 64±10 | 65±10 | 64±10 |

| Men, n (%) | 55,441 (97) | 9109 (97) | 8315 (97) | 15,963 (98) | 10,703 (98) | 11,351 (97) |

| Black, n (%) | 7624 (15) | 1465 (17) | 1194 (15) | 1970 (13) | 1369 (14) | 1,626 (15) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 51,690 (91) | 8632 (92) | 7721 (91) | 14,713 (90) | 9943 (91) | 10,681 (92) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 47,813 (84) | 8120 (86) | 7180 (84) | 13,486 (82) | 9153 (83) | 9874 (85) |

| CHD, n (%) | 10,192 (18) | 1802 (19) | 1465 (17) | 2801 (17) | 1877 (17) | 2247 (19) |

| CHF, n (%) | 3981 (7) | 828 (9) | 511 (6) | 986 (6) | 651 (6) | 1005 (9) |

| CVD, n (%) | 4617 (8) | 828 (9) | 689 (8) | 1235 (8) | 857 (8) | 1008 (9) |

| PAD, n (%) | 5682 (10) | 1034 (11) | 841 (10) | 1533 (9) | 1010 (9) | 1264 (11) |

| Chronic lung disease, n (%) | 10,401 (18) | 1805 (19) | 1562 (18) | 2843 (17) | 1926 (18) | 2265 (19) |

| Liver disease, n (%)a | 236 (1) | 40 (1) | 39 (1) | 64 (1) | 41 (1) | 52 (1) |

| Dementia, n (%)a | 350 (1) | 59 (1) | 46 (1) | 86 (1) | 66 (1) | 93 (1) |

| Rheumatologic disease,n (%)a | 707 (1) | 134 (1) | 103 (1) | 189 (1) | 133 (1) | 148 (1) |

| Malignancies, n (%) | 5887 (10) | 984 (11) | 878 (10) | 1607 (10) | 1111 (10) | 1307 (11) |

| Depression, n (%) | 5386 (10) | 1020 (11) | 811 (10) | 1411 (9) | 976 (9) | 1168 (10) |

| HIV/AIDS, n (%)a | 123 (1) | 24 (1) | 18 (1) | 27 (1) | 26 (2) | 28 (1) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 31.9±6.1 | 32.2±6.5 | 31.8±6.0 | 31.7±6.0 | 31.8±6.0 | 31.9±6.2 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 133±17 | 136±18 | 134±17 | 133±16 | 132±16 | 132±17 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 74±11 | 76±11 | 75±11 | 74±11 | 74±10 | 73±11 |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 79±16 | 80±16 | 79±16 | 80±15 | 79±16 | 78±16 |

| Serum albumin, g/dl | 4.1±0.4 | 4.1±0.4 | 4.1±0.4 | 4.1±0.4 | 4.1±0.4 | 4.1±0.4 |

| UACR, mg/g | 13 (6, 29) | 28 (14–78) | 14 (7–31) | 11 (6–21) | 9 (5–22) | 9 (4–20) |

| UACR categories, mg/g | ||||||

| <30 | 43,098 (76) | 4856 (52) | 6308 (74) | 13,349 (82) | 8895 (81) | 9690 (83) |

| 30 to <300 | 12,244 (22) | 3929 (42) | 1995 (23) | 2681 (16) | 1828 (17) | 1811 (16) |

| ≥300 | 1604 (3) | 627 (7) | 233 (3) | 338 (2) | 249 (2) | 157 (1) |

| Statin use, n (%)a | 16,637 (29) | 2754 (29) | 2572 (30) | 4702 (28) | 3205 (29) | 3404 (29) |

| Nonopioid analgesics use, n (%) | 17,537 (31) | 3134 (33) | 2671 (31) | 4819 (29) | 3169 (29) | 3744 (32) |

| RASi use, n (%) | 10,614 (19) | 1936 (21) | 1525 (18) | 2926 (18) | 1991 (18) | 2236 (19) |

| RASi adherence (>80%), n (%) | 29,340 (52) | 5182 (55) | 4330 (51) | 8203 (50) | 5564 (51) | 6061 (52) |

| Per capita income, $ | 24,504 (13,015–35,773) | 23,730 (12,643–34,089) | 24,340 (12,810–35,708) | 24,943 (13,395–37,000) | 25,121 (13,237–36,883) | 24,173 (12,725–34,914) |

| Married, n (%) | 32,854 (60) | 5169 (57) | 4926 (60) | 9671 (61) | 6501 (61) | 6587 (58) |

| Service connected, n (%)a | 23,793 (42) | 3972 (42) | 3557 (42) | 6754 (41) | 4552 (42) | 4958 (43) |

| Living in area with high housing stress, n (%) | 22,732 (40) | 3783 (41) | 3477 (41) | 6216 (38) | 4493 (41) | 4763 (41) |

| Living in area with low education, n (%) | 7065 (13) | 1238 (13) | 1162 (14) | 1907 (12) | 1285 (12) | 1473 (13) |

| Living in area with low employment, n (%) | 4648 (8) | 732 (8) | 716 (9) | 1487 (9) | 848 (8) | 865 (8) |

| Living in area of persistent poverty, n (%)a | 1677 (3) | 260 (3) | 250 (3) | 490 (3) | 355 (3) | 322 (3) |

Data are presented as number (percentage), mean±SD, or median (interquartile range). All P values except variables indicated for comparing differences across categories were statistically significant. UACR, urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio; CHD, coronary heart disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; BMI, body mass index; RASi, renin-angiotensin system inhibitor.

Not statistically significant.

Incident CKD

During a median follow-up of 6.3 years, there was a total of 8194 events of incident CKD (Supplemental Table 3A). The adjusted association between 1-year fold UACR change and incident CKD was nearly linear (P=0.003 for the quadratic term), with better outcome observed with decreases in 1-year fold UACR (Supplemental Figure 2).

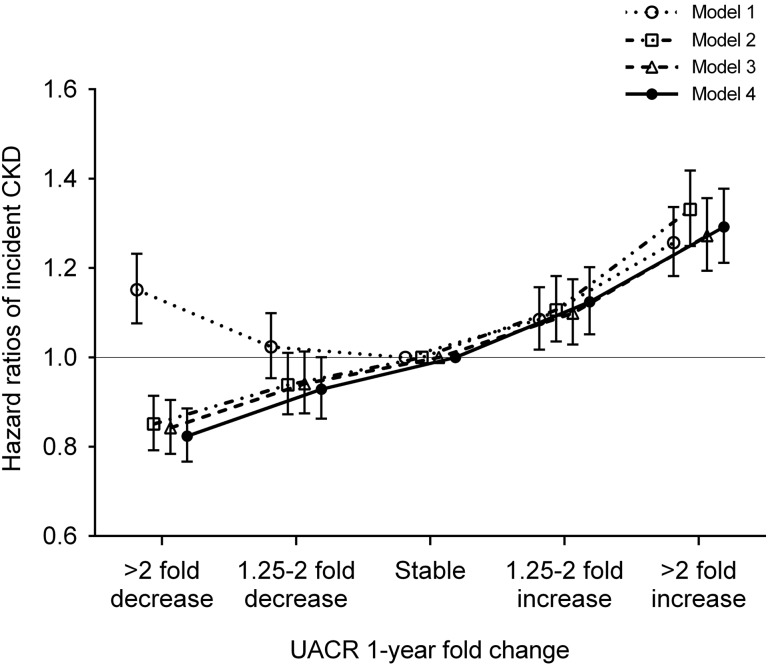

Figure 1 shows the unadjusted and multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) associated with 1-year fold UACR change categories. In the crude model, both increases and decreases in UACR were incrementally associated with higher risk of incident CKD. The associations were substantially modified, particularly for decreases in UACR, after further adjustment for potential confounders and showed a nearly linear relationship (adjusted HRs; 95% confidence intervals [95% CIs] for more than twofold decrease, 1.25- to twofold decrease, 1.25- to twofold increase, and more than twofold increase [versus stable] in UACR; adjusted HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.77 to 0.89; adjusted HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.86 to 1.00; adjusted HR,1.12; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.20; and adjusted HR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.21 to 1.38, respectively, in model 4) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The adjusted association between 1-year fold UACR changes and incident CKD showed a nearly linear relationship. Models represent unadjusted association (model 1); associations after adjustment for age, sex, race, baseline eGFR, and log-transformed UACR (model 2); model 2 variables plus comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral arterial disease, chronic lung disease, liver disease, dementia, rheumatic disease, malignancy, depression, and HIV/AIDS; model 3); and model 3 plus baseline body mass index, systolic BP, diastolic BP, slopes of systolic BP and eGFR, use of statins and nonopioid analgesics at baseline, renin-angiotensin system inhibitor (RASi) treatment status (four categories on the basis of RASi use at the dates of the first and last UACR measurements during the baseline period [i.e., use at both, either, or neither dates]), and RASi adherence (model 4).

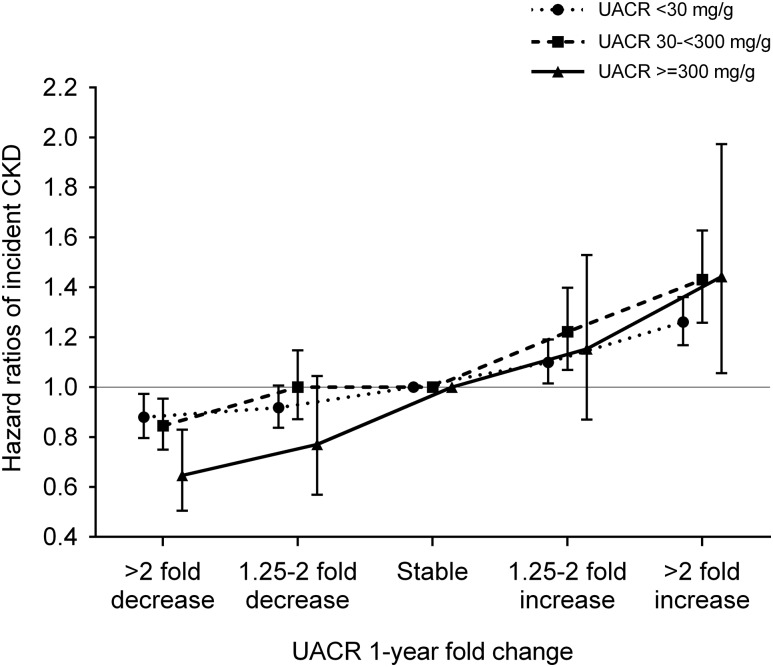

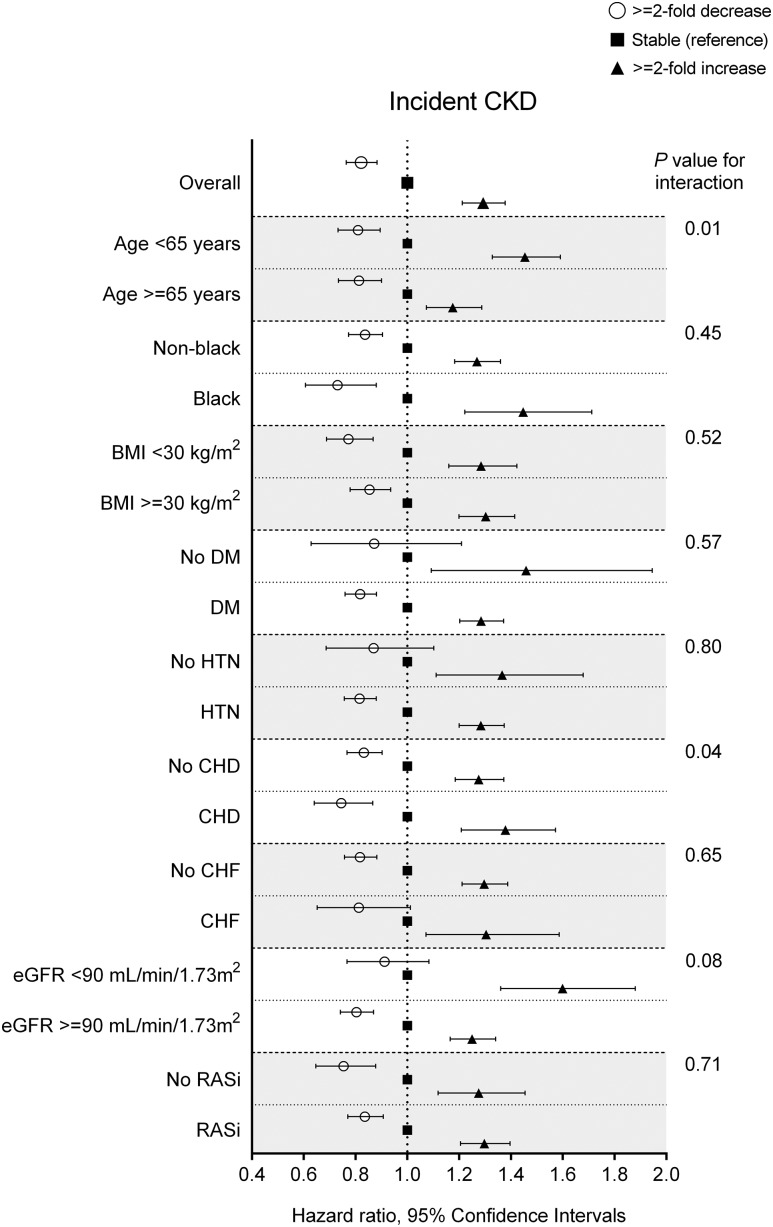

In subgroup analyses, a similar trend of association was observed in patients with different baseline UACR levels (P for interaction =0.05) (Figure 2) and different numbers of UACR measurements during the baseline period (Supplemental Figure 3A) as well as in other examined subgroups with statistically significant interactions with age and coronary heart disease (Figure 3). Results were largely consistent after accounting for death as a competing risk, imputing missing data, or further adjusting for additional covariates (Supplemental Tables 4–6). A similar near-linear association was observed for UACR changes estimated by ordinary least squares regression (Supplemental Figure 4A), whereas the association with decreasing UACR was null for UACR changes estimated by linear mixed effects models (Supplemental Figure 5A).

Figure 2.

A similar trend of association was observed in patients with different baseline UACR levels. Data are adjusted for age, sex, race, baseline eGFR, log-transformed UACR, comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral arterial disease, chronic lung disease, liver disease, dementia, rheumatic disease, malignancy, depression, and HIV/AIDS), baseline body mass index, systolic BP, diastolic BP, slopes of systolic BP and eGFR, use of statins and nonopioid analgesics at baseline, renin-angiotensin system inhibitor (RASi) treatment status (four categories on the basis of RASi use at the dates of the first and last UACR measurements during the baseline period [i.e., use at both, either, or neither dates]), and RASi adherence. P for interaction =0.05.

Figure 3.

The associations of 1-year fold UACR changes with incident CKD were generally consistent across subgroups. Renin-angiotensin system inhibitor (RASi) indicates patients with any exposure to RASi between the first and last UACR measurement during the 2-year baseline period. Data are adjusted for age, sex, race, baseline eGFR, log-transformed UACR, comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral arterial disease, chronic lung disease, liver disease, dementia, rheumatic disease, malignancy, depression, and HIV/AIDS), baseline body mass index, systolic BP, diastolic BP, slopes of systolic BP and eGFR, use of statins and nonopioid analgesics at baseline, RASi treatment status (four categories on the basis of RASi use at the dates of the first and last UACR measurements during the baseline period [i.e., use at both, either, or neither dates]), and RASi adherence. CHD, coronary heart disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension.

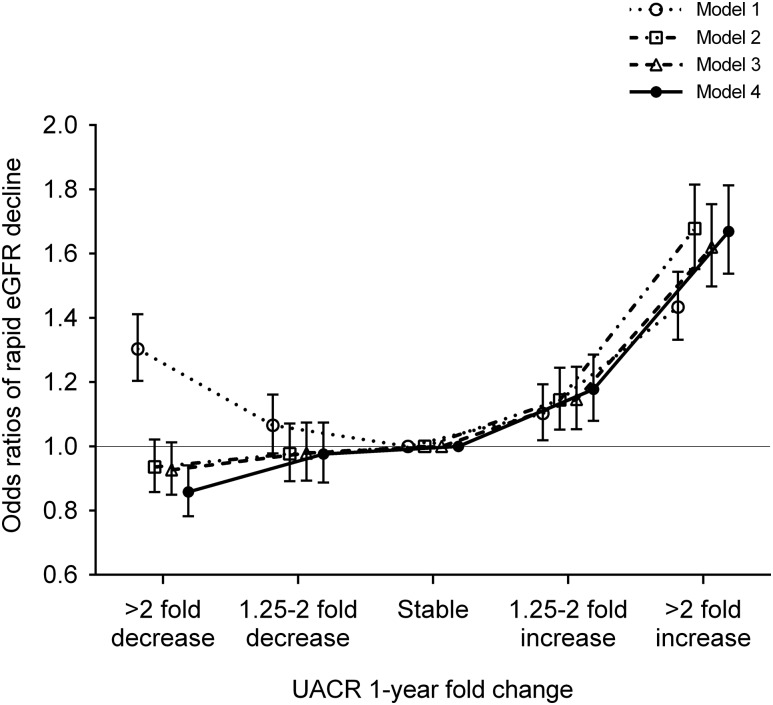

Rapid eGFR Decline

A total of 6512 (12%) patients had rapid eGFR decline during the follow-up period (Supplemental Table 3B). Similar to the associations with incident CKD, the multivariable-adjusted risk associated with rapid eGFR decline was also nearly linear (adjusted odds ratios [ORs]; 95% CI for more than twofold decrease, 1.25- to twofold decrease, 1.25- to twofold increase, and more than twofold increase [versus stable] in UACR; adjusted OR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.78 to 0.94; adjusted OR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.89 to 1.07; adjusted OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.08 to 1.29; and adjusted OR, 1.67; 95% CI, 1.54 to 1.81, respectively, in model 4) (Figure 4). In subgroup analyses, the associations of 1-year fold UACR change with rapid eGFR decline were generally consistent across subgroups (Supplemental Figures 3B, 6, and 7). Baseline UACR qualitatively modified the association of 1-year fold UACR change with rapid eGFR decline, with slightly better outcomes associated with UACR decline among patients with baseline UACR >30 mg/g (Supplemental Figure 6). Findings were robust to several sensitivity analyses (Supplemental Tables 5B and 6B). Analyses with two different indices of UACR change yielded essentially similar associations, except for the associations with decreasing UACR (<−30 mg/g per year), which were null and greater for UACR changes estimated by ordinary least squares regression models and linear mixed effects models, respectively (Supplemental Figures 4B and 5B).

Figure 4.

The adjusted association between 1-year fold UACR changes and rapid eGFR decline was nearly linear. Models represent unadjusted association (model 1); associations after adjustment for age, sex, race, baseline eGFR, and log-transformed UACR (model 2); model 2 variables plus comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral arterial disease, chronic lung disease, liver disease, dementia, rheumatic disease, malignancy, depression, and HIV/AIDS; model 3); and model 3 plus baseline body mass index, systolic BP, diastolic BP, slopes of systolic BP and eGFR, use of statins and nonopioid analgesics at baseline, renin-angiotensin system inhibitor (RASi) treatment status (four categories on the basis of RASi use at the dates of the first and last UACR measurements during the baseline period [i.e., use at both, either, or neither dates]), and RASi adherence (model 4).

Discussion

In this large cohort of United States veterans with eGFR≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, we found that relative changes in UACR over a 1-year interval were linearly associated with subsequent risk of incident CKD and rapid eGFR decline independent of known kidney disease risk factors.

Our findings are generally consistent with previous observational studies that investigated the associations of changes in UACR (defined by single first and last measurements) with the risk of kidney outcomes (19,20,35). Among 31,732 individuals from the Swedish Population Registry, Carrero et al. (20) found that relative changes in UACR over a 1-, 2-, or 3-year interval were consistently and linearly associated with subsequent risk of ESRD, with significantly higher and lower risks seen in those with greater increases and reductions in UACR, respectively. In contrast, another study offered seemingly conflicting evidence on the kidney risk associated with decreases in UACR, showing no association between remission of UACR and the risk of subsequent kidney events (21). These conflicting results may be partly explained by the different populations across studies (e.g., patients with higher [versus lower] baseline UACR showed stronger associations in our study) and/or different analytic methods to express changes in UACR. Indeed, slightly discrepant associations of decreasing UACR with incident CKD were also observed in our study when using different approaches to estimate changes in UACR (i.e., absolute versus relative changes). The two-measurement approach used in our primary analyses is simple and easy to implement in real world settings, but it may be subject to potential intraindividual variability of UACR over time. More sophisticated modeling techniques, such as generalized estimating equations and linear mixed effects models, might thus be preferable for the assessment of UACR changes if multiple measurements were available, just as proposed for the assessment of eGFR trajectories (34), but may be less applicable in daily clinical practice. In this context, our study is, to our knowledge, the first to investigate the associations of UACR changes with subsequent incident CKD by expressing the exposure as absolute changes in UACR (i.e., UACR slope) as well as relative changes in UACR (i.e., 1-year fold UACR changes).

There are several plausible explanations for the underlying mechanisms of the observed near-linear association between UACR changes and adverse kidney outcomes. In line with previous findings on the possible biologic link between albuminuria and cardiovascular events, it is likely that an increase in UACR is a manifestation of worsened generalized vascular dysfunction, particularly endothelial dysfunction, as proposed in the Steno hypothesis (36). Increasing UACR might also reflect increased single-nephron hyperfiltration accompanied by the decrease in the number of functional nephrons (i.e., compensatory hyperfiltration of the remaining nephrons) as well as glycocalyx dysfunction in the glomerular endothelium, both of which are risk factors for subsequent glomerulosclerosis (37–39). Recent evidence also suggests that increased glomerular albumin leakage increases the exposure and uptake of excessive albumin in proximal tubular cells, which in turn, trigger the activation of intracellular signaling pathways that induces the release of inflammatory, vasoactive, and fibrotic substances (40–43). These pathophysiologic processes collectively lead to tubulointerstitial damage and could ultimately result in irreversible kidney damage.

In contrast with the association of increase in UACR with poorer kidney outcomes, we did not find similar associations for decreases in UACR when we expressed UACR changes as slopes, particularly for the slopes estimated by linear mixed effects models, but observed null or slightly worse kidney outcomes in patients who experienced larger absolute decreases in UACR over time. This seemingly counterintuitive finding may be due to the imperfect nature of modeling techniques for UACR slopes (e.g., single outliers causing misclassification of slope categories) as well as residual confounding from baseline albuminuria, which has substantial biologic variability. However, decreases in UACR may not always be the result of improving or resolving kidney pathology. In addition to being a manifestation of endothelial dysfunction, UACR is also a marker of intraglomerular pressure, which is maintained by glomerular autoregulation under normal circumstances. In patients with diabetes and persistent albuminuria (i.e., with nephropathy) accompanied by impaired glomerular autoregulation (44,45), for example, decreases in UACR may represent their decreased ability to adapt to lower kidney perfusion pressures (46), which could cause ischemic kidney injury. Therefore, it is possible that large decreases in UACR could identify some vulnerable patients at high risk for ischemic kidney damage, which may overwhelm the physiologic benefits of reduced UACR when reaching a certain threshold. It is also important to note that similar associations have been reported between decreases in UACR and cardiovascular events or mortality in different patient populations (21,47), and very low UACR levels have been associated with higher mortality and poorer kidney outcomes in patients with advanced CKD (48).

Our results may have several clinical implications. Given its robust associations with kidney outcomes, a relative change in UACR over a 1-year interval could potentially be used as a surrogate for CKD progression. The slightly discrepant associations of decreasing UACR with kidney outcomes depending on different indices of changes in UACR raise the need to determine an optimal modeling technique to express changes in UACR over time. In addition, given that a decrease in UACR may be a multifactorial phenomenon potentially representing a beneficial evolution of kidney disease (e.g., as a result of therapy or spontaneous resolution), various pathophysiologic conditions affecting the glomeruli, or a combination of these, our findings suggest that caution is warranted when interpreting decreases in UACR in terms of prognostication of future risk of adverse clinical outcomes. A true association of changes in UACR, particularly decreases in UACR, with kidney events and the optimal intervention to lower elevated UACR toward improving kidney outcomes across different patient populations may deserve future prospective studies, including clinical trials.

Our study results must be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, most of our patients were United States veterans who were men; hence, the results may not apply to women or patients from other geographical areas. Second, because UACR is not universally available and is usually tested in patients with underlying glomerular diseases, such as diabetic nephropathy, hypertensive nephrosclerosis, or GN, our analytic cohort consisted mostly of older patients with diabetes and/or hypertension, which may also limit the generalizability of our findings. Also of note, only <2% (i.e., 56,946 subjects) of 3,582,478 patients in our original cohort had sufficient albuminuria data available, and thus, we cannot ignore the potential effect of selection bias, such that our analytic sample may reflect individuals whose treating physician thought it prudent to collect multiple urine samples for UACR assessment. Third, because this was an observational study, only associations, but no cause-effect relationships, can be inferred. Most importantly, we cannot conclude that the risk of kidney events associated with various changes in UACR, particularly with larger decreases in UACR, is equal to the risk imparted by the same UACR changes when they occur as a result of therapeutic interventions in clinical practice. Therefore, it must be emphasized that our findings on the inconsistent associations with decreasing UACR depending on different indices of UACR changes should not divert clinicians’ efforts from lowering elevated UACR to prevent CKD progression. Finally, as with all observational studies, we cannot eliminate the possibility of an effect from unmeasured confounders, such as smoking history.

In conclusion, in this large nationwide cohort of United States veterans, relative changes in UACR over a 1-year interval were associated with subsequent risk of incident CKD and rapid eGFR decline. Further studies are warranted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of the observed associations and test whether active interventions aimed at lowering elevated albuminuria can improve kidney outcomes.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant R01DK096920 (to K.K.-Z. and C.P.K.) and is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Memphis Veterans Affairs Medical Center and the Long Beach Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Support for the Veterans Affairs/Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services data is provided by Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development, Veterans Affairs Information Resource Center projects SDR 02-237 and 98-004.

The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. K.K.-Z. and C.P.K. are employees of the US Department of Veterans Affairs. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as official policy or interpretation of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US Government. The results of this paper have not been published previously in whole or part.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.02720317/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hillege HL, Fidler V, Diercks GF, van Gilst WH, de Zeeuw D, van Veldhuisen DJ, Gans RO, Janssen WM, Grobbee DE, de Jong PE; Prevention of Renal and Vascular End Stage Disease (PREVEND) Study Group : Urinary albumin excretion predicts cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality in general population. Circulation 106: 1777–1782, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klausen K, Borch-Johnsen K, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Jensen G, Clausen P, Scharling H, Appleyard M, Jensen JS: Very low levels of microalbuminuria are associated with increased risk of coronary heart disease and death independently of renal function, hypertension, and diabetes. Circulation 110: 32–35, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romundstad S, Holmen J, Kvenild K, Hallan H, Ellekjaer H: Microalbuminuria and all-cause mortality in 2,089 apparently healthy individuals: A 4.4-year follow-up study. The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT), Norway. Am J Kidney Dis 42: 466–473, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yuyun MF, Khaw KT, Luben R, Welch A, Bingham S, Day NE, Wareham NJ; European Prospective Investigation into Cancer in Norfolk (EPIC-Norfolk) population study : Microalbuminuria independently predicts all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in a British population: The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer in Norfolk (EPIC-Norfolk) population study. Int J Epidemiol 33: 189–198, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, Woodward M, Levey AS, de Jong PE, Coresh J, Gansevoort RT; Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium : Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: A collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet 375: 2073–2081, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerstein HC, Mann JF, Yi Q, Zinman B, Dinneen SF, Hoogwerf B, Hallé JP, Young J, Rashkow A, Joyce C, Nawaz S, Yusuf S; HOPE Study Investigators : Albuminuria and risk of cardiovascular events, death, and heart failure in diabetic and nondiabetic individuals. JAMA 286: 421–426, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Mosconi L, Pisoni R, Remuzzi G: Urinary protein excretion rate is the best independent predictor of ESRF in non-diabetic proteinuric chronic nephropathies. “Gruppo Italiano di Studi Epidemiologici in Nefrologia” (GISEN). Kidney Int 53: 1209–1216, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ninomiya T, Perkovic V, de Galan BE, Zoungas S, Pillai A, Jardine M, Patel A, Cass A, Neal B, Poulter N, Mogensen CE, Cooper M, Marre M, Williams B, Hamet P, Mancia G, Woodward M, Macmahon S, Chalmers J; ADVANCE Collaborative Group : Albuminuria and kidney function independently predict cardiovascular and renal outcomes in diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1813–1821, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Astor BC, Matsushita K, Gansevoort RT, van der Velde M, Woodward M, Levey AS, Jong PE, Coresh J, Astor BC, Matsushita K, Gansevoort RT, van der Velde M, Woodward M, Levey AS, de Jong PE, Coresh J, El-Nahas M, Eckardt KU, Kasiske BL, Wright J, Appel L, Greene T, Levin A, Djurdjev O, Wheeler DC, Landray MJ, Townend JN, Emberson J, Clark LE, Macleod A, Marks A, Ali T, Fluck N, Prescott G, Smith DH, Weinstein JR, Johnson ES, Thorp ML, Wetzels JF, Blankestijn PJ, van Zuilen AD, Menon V, Sarnak M, Beck G, Kronenberg F, Kollerits B, Froissart M, Stengel B, Metzger M, Remuzzi G, Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Heerspink HJ, Brenner B, de Zeeuw D, Rossing P, Parving HH, Auguste P, Veldhuis K, Wang Y, Camarata L, Thomas B, Manley T; Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium : Lower estimated glomerular filtration rate and higher albuminuria are associated with mortality and end-stage renal disease. A collaborative meta-analysis of kidney disease population cohorts. Kidney Int 79: 1331–1340, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gansevoort RT, Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, Woodward M, Levey AS, de Jong PE, Coresh J; Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium : Lower estimated GFR and higher albuminuria are associated with adverse kidney outcomes. A collaborative meta-analysis of general and high-risk population cohorts. Kidney Int 80: 93–104, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hemmelgarn BR, Manns BJ, Lloyd A, James MT, Klarenbach S, Quinn RR, Wiebe N, Tonelli M; Alberta Kidney Disease Network : Relation between kidney function, proteinuria, and adverse outcomes. JAMA 303: 423–429, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group : KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 3: 1–150, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stevens PE, Levin A; Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Chronic Kidney Disease Guideline Development Work Group Members : Evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: Synopsis of the kidney disease: Improving global outcomes 2012 clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med 158: 825–830, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heerspink HJ, Kröpelin TF, Hoekman J, de Zeeuw D; Reducing Albuminuria as Surrogate Endpoint (REASSURE) Consortium : Drug-induced reduction in albuminuria is associated with subsequent renoprotection: A meta-analysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 2055–2064, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lambers Heerspink HJ, Gansevoort RT: Albuminuria is an appropriate therapeutic target in patients with CKD: The pro View. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1079–1088, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fried LF, Lewis J: Albuminuria is not an appropriate therapeutic target in patients with CKD: The con view. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1089–1093, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cravedi P, Ruggenenti P, Remuzzi G: Proteinuria should be used as a surrogate in CKD. Nat Rev Nephrol 8: 301–306, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson A: Proteinuria as a surrogate end point--more data are needed. Nat Rev Nephrol 8: 306–309, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmieder RE, Mann JF, Schumacher H, Gao P, Mancia G, Weber MA, McQueen M, Koon T, Yusuf S; ONTARGET Investigators : Changes in albuminuria predict mortality and morbidity in patients with vascular disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1353–1364, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carrero JJ, Grams ME, Sang Y, Ärnlöv J, Gasparini A, Matsushita K, Qureshi AR, Evans M, Barany P, Lindholm B, Ballew SH, Levey AS, Gansevoort RT, Elinder CG, Coresh J: Albuminuria changes are associated with subsequent risk of end-stage renal disease and mortality. Kidney Int 91: 244–251, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Boer IH, Gao X, Cleary PA, Bebu I, Lachin JM, Molitch ME, Orchard T, Paterson AD, Perkins BA, Steffes MW, Zinman B; Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (DCCT/EDIC) Research Group : Albuminuria changes and cardiovascular and renal outcomes in type 1 diabetes: The DCCT/EDIC study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1969–1977, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen JS: Intra-individual variation of overnight urinary albumin excretion in clinically healthy middle-aged individuals. Clin Chim Acta 243: 95–99, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mogensen CE, Vestbo E, Poulsen PL, Christiansen C, Damsgaard EM, Eiskjaer H, Frøland A, Hansen KW, Nielsen S, Pedersen MM: Microalbuminuria and potential confounders. A review and some observations on variability of urinary albumin excretion. Diabetes Care 18: 572–581, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kovesdy CP, Norris KC, Boulware LE, Lu JL, Ma JZ, Streja E, Molnar MZ, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Association of race with mortality and cardiovascular events in a large cohort of US veterans. Circulation 132: 1538–1548, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gosmanova EO, Lu JL, Streja E, Cushman WC, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kovesdy CP: Association of medical treatment nonadherence with all-cause mortality in newly treated hypertensive US veterans. Hypertension 64: 951–957, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coresh J, Turin TC, Matsushita K, Sang Y, Ballew SH, Appel LJ, Arima H, Chadban SJ, Cirillo M, Djurdjev O, Green JA, Heine GH, Inker LA, Irie F, Ishani A, Ix JH, Kovesdy CP, Marks A, Ohkubo T, Shalev V, Shankar A, Wen CP, de Jong PE, Iseki K, Stengel B, Gansevoort RT, Levey AS: Decline in estimated glomerular filtration rate and subsequent risk of end-stage renal disease and mortality. JAMA 311: 2518–2531, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kovesdy CP, Bleyer AJ, Molnar MZ, Ma JZ, Sim JJ, Cushman WC, Quarles LD, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Blood pressure and mortality in U.S. veterans with chronic kidney disease: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med 159: 233–242, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kovesdy CP, Lu JL, Molnar MZ, Ma JZ, Canada RB, Streja E, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Bleyer AJ: Observational modeling of strict vs conventional blood pressure control in patients with chronic kidney disease. JAMA Intern Med 174: 1442–1449, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.US Department of Veterans Affairs: VA Information Resource Center. Available at: http://www.virec.research.va.gov/Resources/Info-About-VA-Data.asp. Accessed August 16, 2017

- 30.Choudhry NK, Shrank WH, Levin RL, Lee JL, Jan SA, Brookhart MA, Solomon DH: Measuring concurrent adherence to multiple related medications. Am J Manag Care 15: 457–464, 2009 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levin A, Stevens PE: Summary of KDIGO 2012 CKD Guideline: Behind the scenes, need for guidance, and a framework for moving forward. Kidney Int 85: 49–61, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sumida K, Molnar MZ, Potukuchi PK, Thomas F, Lu JL, Matsushita K, Yamagata K, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kovesdy CP: Constipation and Incident CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 1248–1258, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sohn MW, Arnold N, Maynard C, Hynes DM: Accuracy and completeness of mortality data in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Popul Health Metr 4: 2, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leffondre K, Boucquemont J, Tripepi G, Stel VS, Heinze G, Dunkler D: Analysis of risk factors associated with renal function trajectory over time: A comparison of different statistical approaches. Nephrol Dial Transplant 30: 1237–1243, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmieder RE, Schutte R, Schumacher H, Böhm M, Mancia G, Weber MA, McQueen M, Teo K, Yusuf S; ONTARGET/TRANSCEND investigators : Mortality and morbidity in relation to changes in albuminuria, glucose status and systolic blood pressure: An analysis of the ONTARGET and TRANSCEND studies. Diabetologia 57: 2019–2029, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deckert T, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Borch-Johnsen K, Jensen T, Kofoed-Enevoldsen A: Albuminuria reflects widespread vascular damage. The Steno hypothesis. Diabetologia 32: 219–226, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rabelink TJ, de Zeeuw D: The glycocalyx--linking albuminuria with renal and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 11: 667–676, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brenner BM, Lawler EV, Mackenzie HS: The hyperfiltration theory: A paradigm shift in nephrology. Kidney Int 49: 1774–1777, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Melsom T, Stefansson V, Schei J, Solbu M, Jenssen T, Wilsgaard T, Eriksen BO: Association of increasing GFR with change in albuminuria in the general population. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 2186–2194, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zoja C, Donadelli R, Colleoni S, Figliuzzi M, Bonazzola S, Morigi M, Remuzzi G: Protein overload stimulates RANTES production by proximal tubular cells depending on NF-kappa B activation. Kidney Int 53: 1608–1615, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dixon R, Brunskill NJ: Activation of mitogenic pathways by albumin in kidney proximal tubule epithelial cells: Implications for the pathophysiology of proteinuric states. J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1487–1497, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang Y, Rangan GK, Tay YC, Wang Y, Harris DC: Induction of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 by albumin is mediated by nuclear factor kappaB in proximal tubule cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1204–1213, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stephan JP, Mao W, Filvaroff E, Cai L, Rabkin R, Pan G: Albumin stimulates the accumulation of extracellular matrix in renal tubular epithelial cells. Am J Nephrol 24: 14–19, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Osterby R: Microalbuminuria in diabetes mellitus--is there a structural basis? Nephrol Dial Transplant 10: 12–14, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Christensen PK, Hansen HP, Parving H-H: Impaired autoregulation of GFR in hypertensive non-insulin dependent diabetic patients. Kidney Int 52: 1369–1374, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palmer BF: Renal dysfunction complicating the treatment of hypertension. N Engl J Med 347: 1256–1261, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Romundstad S, Hatlen G, Hallan SI: Long-term changes in albuminuria: Underlying causes and future mortality risk in a 20-year prospective cohort: The Nord-Trøndelag Health (HUNT) Study. J Hypertens 34: 2081–2089, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kovesdy CP, Lott EH, Lu JL, Malakauskas SM, Ma JZ, Molnar MZ, Kalantar-Zadeh K: Outcomes associated with microalbuminuria: Effect modification by chronic kidney disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 61: 1626–1633, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.