Abstract

Objective

To report the changes to UK medicine which doctors who have emigrated tell us would increase their likelihood of returning to a career in UK medicine.

Design

Questionnaire survey.

Setting

UK-trained medical graduates.

Participants

Questionnaires were sent 11 years after graduation to 7158 doctors who qualified in 1993 and 1996 in the UK: 4763 questionnaires were returned. Questionnaires were sent 17 and 19 years after graduation to the same cohorts: 4554 questionnaires were returned.

Main outcome measures

Comments from doctors working abroad about changes needed to UK medicine before they would return.

Results

Eleven years after graduation, 290 (6%) of respondents were working in medicine abroad; 277 (6%) were doing so 17/19 years after graduation. Eleven years after graduation, 53% of doctors working abroad indicated that they did not intend to return, and 71% did so 17/19 years after graduation. These respondents reported a number of changes which would need to be made to UK medicine in order to increase the likelihood of them returning. The most frequently mentioned changes cited concerned ‘politics/management/funding’, ‘pay/pension’, ‘posts/security/opportunities’, ‘working conditions/hours’, and ‘factors outside medicine’.

Conclusions

Policy attention to factors including funding, pay, management and particularly the clinical–political interface, working hours, and work–life balance may pay dividends for all, both in terms of persuading some established doctors to return and, perhaps more importantly, encouraging other, younger doctors to believe that the UK and the National Health Service can offer them a satisfying and rewarding career.

Keywords: Physicians, career choice, medical staff, attitude of health personnel, emigration, travel

Introduction

According to the UK government, it costs over £200,000 to train a doctor in the UK.1 Retaining these doctors in the UK’s National Health Service is seen by many to be desirable.1,2 However, the numbers of graduates entering National Health Service specialist training have declined sharply in recent years. In 2016 the UK Foundation Office reported that only 50.4% of new medical graduates went straight into specialty training following their two postgraduate foundation training years, compared with 72% in 2011.3 Over the five years after 2011 the percentage going into specialist training at this stage was, successively, 72, 67, 64, 58, 52, and 50%. Recently there have been significant numbers of unfilled specialty training posts.4

In the UK, doctors can apply for a Certificate of Good Standing to enable them to work abroad. The numbers of doctors applying for these certificates rose by 12% between 2008 and 2013.5 However, the number of Certificate of Good Standing applications is not a clear indicator of the actual number of doctors working abroad, since not all doctors who apply for them will eventually work abroad, and some doctors may work abroad for a short duration. A study of UK-trained doctors who graduated between 1974 and 2002 found that 88% of home-based doctors (i.e. those who lived in Great Britain at the time of entry to medical school) remained in the National Health Service two years after qualification, and that 85% of contactable doctors were still working in the National Health Service 15 years after qualification (doctors who graduated between 1974 and 1988).6 This study also found that attrition from the National Health Service was no greater among the more recent cohorts, although they could only, as yet, be followed up for shorter periods of time.

The UK is a net exporter of doctors to the United States, Australia, and Canada.7 UK-trained doctors working in New Zealand reported emigrating for lifestyle reasons, desire to travel, and dissatisfaction with the National Health Service.8 A more recent study found similar motivational factors: 96% of UK-trained doctors working in New Zealand were attracted by the pull factor of quality of life and 65% were ‘pushed’ by a motivation to leave the National Health Service.9

Our aim in this paper is to report the changes to UK medicine which doctors who have emigrated tell us would increase their likelihood of returning to a career in UK medicine. We report data from two cohorts of senior doctors who graduated from UK medical schools in 1993 and 1996.

Methods

The UK Medical Careers Research Group surveyed the UK medical graduates of 1993 and 1996. We sent postal questionnaires to the 1993 cohort in 2004 and 2010. The 1996 cohort was surveyed in 2007 and 2015. Up to four reminders were sent to non-respondents. Further details of the methodology are available elsewhere.10

Doctors were asked to describe their current employment situation using one of the following options: ‘Working in medicine, in the UK’, ‘Working in medicine, outside the UK’, ‘Working outside medicine’, and ‘Not in paid employment’. The survey questionnaires used were broadly based and covered many aspects of the doctors’ career intentions, career progression, and views. Specifically, we asked doctors who indicated that they were working in medicine outside the UK to complete the following additional questions: ‘Do you plan to return to UK medicine?’ (with the options being Yes-definitely, Yes-probably, Undecided, No-probably not, and No-definitely not), and ‘What changes to UK medicine, if any, would increase your likelihood of returning?’ (with the doctors being asked to respond in their own words).

We analysed the quantitative data by cohort, sex, and specialty group using cross-tabulation and χ2 statistics (reporting Yates’s continuity correction where there was only one degree of freedom). Respondents were grouped for analysis into four specialty groups: hospital medical specialties, hospital surgical specialties, general practice, and other hospital specialties combined (paediatrics, emergency medicine, obstetrics and gynaecology, anaesthetics, radiology, clinical oncology, pathology, and psychiatry).

In order to analyse the open question about changes to UK medicine, we developed a coding scheme to reflect themes and sub-themes raised within the answers. Two researchers independently coded the answers, blind to knowledge of which survey each comment corresponded to, resolving differences in coding through discussion. Each comment was assigned up to four codes. We protected the anonymity of doctors by redacting references to hospital trusts, medical schools, and other identifying information.

Results

Response rates

Over the four surveys conducted, the response rate from contactable doctors was 69.1% (9317/13489): see Table 1 for the response for each survey.

Table 1.

Survey response and numbers who commented on changes needed to UK medicine.

| 1996 graduates |

1993 graduates |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 survey | 2007 survey | 2010 survey | 2004 survey | |

| Contacted | 2860 | 3668 | 3471 | 3490 |

| Replied | 2047 | 2452 | 2507 | 2311 |

| Response (%) | 71.6 | 66.8 | 72.2 | 66.2 |

| Working in medicine outside the UK | 108 | 145 | 169 | 145 |

| Commented on changes | 83 | 112 | 109 | 103 |

| Men | 51 | 64 | 66 | 50 |

| Women | 32 | 48 | 43 | 53 |

| General practitioners | 16 | 22 | 24 | 17 |

| Medical specialists | 16 | 13 | 11 | 22 |

| Surgeons | 11 | 18 | 10 | 15 |

| Other hospital specialists | 34 | 45 | 35 | 42 |

| Commented on both occasions | 20 | 40 | ||

Respondents who were working outside the UK

Eleven years after graduation, in 2004 and 2007, the doctors who graduated, respectively, in 1993 and 1996 were asked about their current employment situation. Of 4535 who answered the question, 290 (6.4%) were working in medicine outside the UK. Seventeen and 19 years after graduation, respectively, 4533 doctors from the same graduation cohorts answered the same question and 277 (6.1%) were working in medicine outside the UK (Table 1). These respondents were asked about their level of intention to return to the UK, and the changes needed, in their view, to UK medicine which would increase their likelihood of returning.

Plans to return to UK medicine of doctors working in medicine abroad

Of the 290 doctors working abroad in year 11, four doctors did not indicate their level of intention to return to the UK. Most of the other 286 (52.5%) did not intend to return, 16.9% were undecided, and 30.4% intended to return. Of the 277 doctors working abroad in years 17 and 19, six doctors did not indicate their intention. Most of the other 271 (70.5%) responded that they did not intend to return, 17.7% were undecided, and 12.8% indicated that they did intend to return.

Changes to UK medicine that would increase doctors’ likelihood of returning

Of the 290 doctors working in medicine abroad 11 years after graduation, 215 answered the question ‘What changes to UK medicine, if any, would increase your likelihood of returning?’; 192 of the 277 doctors working abroad in years 17/19 answered the question (Table 1). A small number in each cohort commented on both occasions. The gender and specialty group breakdown of those who commented is given in Table 1.

Eleven years after graduation, four work-related factors dominated the comments (Table 2): ‘political/management/funding’ issues, cited by 24.2% of commenters; ‘pay/pension’ (20.9%); ‘posts/security/opportunities’ (18.6%); and ‘working conditions/hours’ (18.1%). Additionally, ‘factors outside medicine’ were cited by 17.7%, and 14.9% said ‘none’ (i.e. there was, for them, no change to UK medicine that would encourage them to return). Women were significantly more likely than men to cite ‘factors outside medicine’ (27.7% women, 8.8% men; = 11.9, p < 0.001). Men were significantly more likely than women to cite ‘status, autonomy, morale’ (1.0% women, 12.3% men; = 8.9, p < 0.01). Other gender differences were small.

Table 2.

Comments about changes to UK medicine which would increase the likelihood of doctors returning to UK medicine*, percentages and numbers: 11 and 17/19 years after graduation.

| 11 years after graduation |

17/19 years after graduation |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theme | N | Percentage of commenters* (N = 215) | Percentage of those working abroad (N = 290) | N | Percentage of commenters* (N = 192) | Percentage of those working abroad (N = 277) |

| Political/management/funding | 52 | 24.2 | 17.9 | 61 | 31.8 | 22.0 |

| Pay/pension | 45 | 20.9 | 15.5 | 47 | 24.5 | 17.0 |

| Posts/security/opportunities | 40 | 18.6 | 13.8 | 26 | 13.5 | 9.4 |

| Working conditions/hours | 39 | 18.1 | 13.4 | 39 | 20.3 | 14.1 |

| Factors outside medicine | 38 | 17.7 | 13.1 | 30 | 15.6 | 10.8 |

| None | 32 | 14.9 | 11.0 | 35 | 18.2 | 12.6 |

| Retraining/accreditation/revalidation | 20 | 9.3 | 6.9 | 18 | 9.4 | 6.5 |

| Specialty related | 19 | 8.8 | 6.6 | 25 | 13.0 | 9.0 |

| Status, autonomy, morale | 15 | 7.0 | 5.2 | 23 | 12.0 | 8.3 |

| Other | 9 | 4.2 | 3.1 | 2 | 1.0 | 0.7 |

| Administration/bureaucracy | 6 | 2.8 | 2.1 | 14 | 7.3 | 5.1 |

| Private work | 4 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 6 | 3.1 | 2.2 |

Some doctors gave more than one reason and we counted each reason. Eleven years after graduation 75 of the 290 doctors who said they were ‘working in medicine outside the UK’ did not provide comments, and 85 of the 277 doctors 17/19 years after graduation did not provide comments.

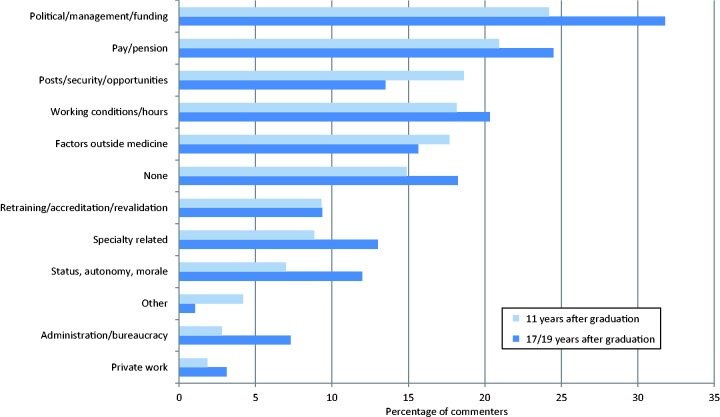

Seventeen/nineteen years after graduation, some factors were mentioned by more doctors than previously (Figure 1, Table 2): 31.8% of commenters cited ‘political/management/funding’, 24.5% cited ‘pay/pension’, 20.3% cited ‘working conditions/hours’, and 18.2% cited ‘none’. Two other factors also gained in importance and were mentioned by over 10% of commenters: ‘specialty related’ (13.0%) and ‘status, autonomy, morale’ (12.0%). Only two factors were mentioned by fewer doctors than previously: ‘posts/security/opportunities’ (13.5%), ‘factors outside medicine’ (15.6%). No significant differences were observed between men and women doctors.

Figure 1.

Comments about changes to UK medicine which would increase the likelihood of doctors returning to UK medicine, percentages and numbers: 11 and 17/19 years after graduation.

Table 3 displays the results of Table 2, showing each of the four surveys separately.

Table 3.

Comments about changes to UK medicine which would increase the likelihood of doctors returning to UK medicine, percentages and numbers: by survey year.

| Count |

Percentage |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 (n = 103) | 2007 (n = 112) | 2010 (n = 109) | 2015 (n = 83) | 2004 (n = 103) | 2007 (n = 112) | 2010 (n = 109) | 2015 (n = 83) | |

| Political/management/funding | 20 | 32 | 28 | 33 | 19.4 | 28.6 | 25.7 | 39.8 |

| Pay/pension | 31 | 14 | 19 | 28 | 30.1 | 12.5 | 17.4 | 33.7 |

| Posts/security/opportunities | 14 | 26 | 19 | 7 | 13.6 | 23.2 | 17.4 | 8.4 |

| Working conditions/hours | 22 | 17 | 16 | 23 | 21.4 | 15.2 | 14.7 | 27.7 |

| Factors outside medicine | 22 | 16 | 18 | 12 | 21.4 | 14.3 | 16.5 | 14.5 |

| None | 11 | 21 | 23 | 12 | 10.7 | 18.8 | 21.1 | 14.5 |

| Retraining/accreditation/ revalidation | 11 | 9 | 11 | 7 | 10.7 | 8.0 | 10.1 | 8.4 |

| Specialty related | 8 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 7.8 | 9.8 | 11.0 | 15.7 |

| Status, autonomy, morale | 7 | 8 | 10 | 13 | 6.8 | 7.1 | 9.2 | 15.7 |

| Other | 6 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5.8 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 0.0 |

| Administration/bureaucracy | 3 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 5.5 | 9.6 |

| Private work | 4 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 3.9 | 0.0 | 3.7 | 2.4 |

Comments which were representative of each theme mentioned by the respondents

We summarise the doctors’ comments below and provide what we consider to be representative quotes under each heading. For each quote selected we display it, in full, in Box 1. We also provide each quoted doctor’s gender, number of years after graduation, specialty, grade, and location.

Box 1.

Selected quotations about changes needed to medicine in the UK before doctors will return.

| Quote number | Quote | Sex, year, specialty, grade, and location |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | ‘Less interference from Government. More professional autonomy. Less pressure to continually “do more with less”’ | Male, Y17/19, Radiology Consultant, Canada |

| 2. | ‘Less political micro-management of NHS. Establishing larger centralised service to provide better clinical care’ | Female, Y11, Paediatrics Consultant, Australia |

| 3. | ‘Taking a step back before the Patient Charter before waiting times became more important than patient care … the NHS was a great institution, better than here in France, but governments are hell bent on destroying it!’ | Female, Y11, General Practice Principal, France/Corsica/Monaco |

| 4. | ‘NHS stability (as in less privatisation and better funding generally and allied health staff retention)’ | Female, Y11, Infectious diseases Consultant, Malaysia/Brunei/Singapore |

| 5. | ‘Change in NHS system to private/insurance based’ | Female, Y11, Paediatrics Consultant, Malaysia/Brunei/Singapore |

| 6. | ‘More independence as a practitioner, less dictation to from above non-medical management’ | Female, Y17/19, General Practice Principal, Canada |

| 7. | ‘Widening role of Emergency Medicine by getting rid of 4 hr rule to see/treat/discharge or admit patients’ | Male, Y11, Emergency Medicine Registrar, Australia |

| 8. | ‘Removing free at point of care General Practice consults’ | Male, Y11, General Practice Principal, Australia/Tasmania |

| 9. | ‘A complete overhaul of the health system toward the Australian model. Tax rebate for those who have health insurance, thereby improving the demand for use of free health care by moving the wealthier into private health care’ | Male, Y11, Emergency Medicine Consultant, Australia |

| 10. | ‘Appreciation of UK graduates from Commonwealth nation … over the EU policy. Equal opportunity, based on credential & performance’ | Male, Y17/19, Cardiology Consultant, Malaysia/Brunei/Singapore |

| 11. | ‘Better pay. Better working conditions – less hours’ | Male, Y11, General Practice Principal, Hong Kong |

| 12. | ‘Continued improvements in salary and working hours’ | Female, Y11, Anaesthetics Consultant, New Zealand |

| 13. | ‘Major changes in pay and conditions’ | Male, Y11, Anaesthetics Consultant, Australia |

| 14. | ‘More competitive salary. I earn 50% more than my UK counterparts and pay far less tax’ | Male, Y17/19, Anaesthetics, Malaysia/Brunei/Singapore |

| 15. | ‘Equitable pay in the UK compared to Australia would make returning more attractive should this be a consideration in the future’ | Male, Y17/19, Emergency Medicine Consultant, Australia |

| 16. | ‘If the NHS seemed like a better place to work with better job security and proper training schemes’ | Female, Y11, Anaesthetics Clinical Fellow, Australia |

| 17. | ‘Greater ability to follow an academic career alongside a clinical one (without the clinical commitment impacting on the ability to follow an academic career)’ | Male, Y17/19, Psychiatry, University Professor, Canada |

| 18. | ‘Family-friendly working hours/contract’ | Male, Y11, Anaesthetics, Consultant, Gibraltar |

| 19. | ‘Improved part-time opportunities for specialists’ | Female, Y11, Paediatrics Consultant, Australia |

| 20. | ‘Improved working conditions, better work life balance’ | Female, Y17/19, Psychiatry Consultant, S Atlantic Islands |

| 21. | ‘Please note not just a medical but a lifestyle choice to be out of the UK therefore cannot entirely attribute my decision to a pure career reason’ | Female, Y11, Anaesthetics Consultant, New Zealand |

| 22. | ‘Decision to spend time abroad taken for family not career reasons’ | Female, Y11, General Practice Principal, New Zealand |

| 23. | ‘It has less to do with the UK situation improving and more to do with what is available in Australia where I am now working – including the weather – which I guess the NHS can’t do much about’ | Female, Y17/19, Paediatrics Consultant, Australia |

| 24. | ‘Ease of transfer/reciprocity of specialist training (recognition) gained overseas will be a determining factor’ | Female, Y17/19, Psychiatry Consultant, Australia |

| 25. | ‘The new revalidation system is putting me off’ | Female, Y11, General Practice Principal, General practice, New Zealand |

| 26. | ‘Better working conditions for GPs – longer appointments, less abuse of the NHS. Charging for consultations – as here in NZ – would go a long way’ | Female, Y11, General Practice Principal, General practice, New Zealand |

| 27. | ‘More GP partnerships as opposed to salaried posts, which creates a 2 tier split in the GP profession’ | Female, Y11, General Practice Locum, New Zealand |

| 28. | ‘Complete restructure of Emergency Medicine so it was a real speciality with proper resources’ | Male, Y17/19, Emergency Medicine Consultant, Australia |

| 29. | ‘Emergency Medicine practice to be up to date’ | Female, Y17/19, Emergency Medicine Consultant, New Zealand |

| 30. | ‘Better public opinion, less doctor bashing in media. Currently working in Canada where GPs are respected and appreciated part of the community’ | Female, Y11, General Practice Principal, Canada |

| 31. | ‘Increased professional status, pay & conditions’ | Male, Y11, Anaesthetics University Lecturer, USA |

| 32. | ‘Enjoy working in NZ as actually see sick patients and am “hands on” and not just wading through administration’ | Female, Y11, Emergency Medicine Consultant, New Zealand |

| 33. | ‘Increased clinical contact/focus and reduced bureaucracy/admin/target driven practice’ | Male, Y17/19, General Practice Principal, New Zealand |

| 34. | ‘Better pay, many specialists struggling financially. Incentives to do private practice rather than current disincentives’ | Male, Y17/19, Obstetrics and gynaecology Consultant, Australia |

Quote number cross-refers to the ‘Results’ section. Year denotes the number of years after graduation. NZ, New Zealand; GP, General Practice; NHS, National Health Service.

Political/management/funding

Many doctors raised what they variously called ‘political interference’ or ‘micro-management’ by government regarding the running of the National Health Service (Box 1, quotes 1–3). Some doctors suggested ways to improve clinical care and the stability of the National Health Service. Ideas were varied, including establishing a larger centralised service, less privatisation, moving to a private/insurance-based system, and better funding (Box 1, quotes 2, 4, and 5).

The theme of politics, management, and funding was mentioned by more doctors 17/19 years after graduation compared with 11 years after graduation, but the points raised were similar (see, for example Box 1, quote 6). There were still calls for more funding and more clinical-led management.

Some doctors were concerned about certain government targets or policies. For example, some doctors working in emergency medicine called for the removal of the ‘four hour rule’ within which new patients should be seen (Box 1, quote 7). Some doctors described specific funding mechanisms which they felt would improve UK medicine, such as charging for consultations with a general practitioner and providing a tax rebate for those who have health insurance (Box 1, quotes 8–9).

Many doctors felt that UK immigration laws were too stringent and that it was difficult for non-European Union (EU) migrant doctors to obtain medical positions (Box 1, quote 10).

Pay/pension

Many commenters said that they would want better pay if they were to return to the UK (Box 1, quotes 11–15). Many drew comparisons between the country they were working in and the UK: one doctor earned 50% more than his UK counterparts, and paid less tax (Box 1, quote 14).

Posts/security/opportunities

Several doctors felt that there were insufficient suitable posts in the UK and they would need the prospect of greater job security if they were to return (Box 1, quote 16). A few doctors wanted to see an increase in research opportunities or to be able to work in a combined clinical and academic role (Box 1, quote 17).

Working conditions/hours

Doctors complained about poor working conditions and long working hours in the UK at the same time as calling for higher pay (Box 1, quotes 11–13). Several doctors wanted improved part-time opportunities, and more flexible, family-friendly hours (Box 1, quotes 18–20).

Factors outside medicine/‘Nothing would make me return’

Despite the direction from the question to provide ‘changes to UK medicine which would increase your likelihood of returning’, many respondents replied that no changes would make a difference (‘no changes’, ‘none’, ‘nothing’ were typical replies). Many doctors also said that their decision to work abroad had nothing to do with work issues: factors outside medicine had drawn them to work outside the UK. These factors included the lifestyle in their host country, family reasons, and climate (Box 1, quotes 21–23).

Retraining/accreditation/revalidation

Several doctors felt that their return to UK medicine could be made easier with accreditation assistance and retraining support. One doctor said that the recognition of specialist training gained overseas would be a determining factor (Box 1, quote 24). A few doctors did not like the prospect of revalidation (Box 1, quote 25).

Specialty related

Other changes to UK medicine which were suggested included changes to certain specialties (including better resources). In General Practice, doctors wanted ‘better working conditions’, longer appointments, charges for consultations, more partnership opportunities (Box 1, quotes 26–27). In Emergency Medicine, doctors called for a restructure of the discipline, and more up to date practice (Box 1, quotes 28–29), though the responses did not go into detail.

Status, autonomy, morale

Several doctors felt that the status, autonomy, and morale of doctors in the UK was being eroded (Box 1, quotes 30–31). One doctor, who was working in Canada, believed that general practitioners are more respected there and wanted to see better public opinion of doctors in the UK (Box 1, quote 30).

Administration/bureaucracy

A few doctors suggested that a reduction in administration and bureaucracy would make them more likely to return to the UK. These doctors wanted medicine to be less bureaucratic and more about patient care (Box 1, quotes 32–33).

Private work

Some doctors wanted more opportunity to practice private medicine (Box 1, quote 34).

Discussion

Main findings

Eleven years after graduation, just over one-half of the UK-trained doctors working abroad who responded to our surveys had no intentions of returning to UK medicine; this figure rose to two-thirds of doctors 17/19 years after graduation. Preconditions for returning to UK medicine included less ‘political interference’, more clinical-led management, more funding, higher pay, improved working conditions and hours, more posts, and greater job security. A large number of doctors simply said that nothing could change within UK medicine that would make them return. Similarly, many doctors were working abroad for reasons which were not amenable to policy changes in UK medicine, such as climate, family, and lifestyle. It is unclear that proposals such as the UK’s Health Secretary’s recent announcement that, from 2018, newly trained doctors will be required to work for the National Health Service for four years1 would be practical or enforceable, given the combination of professional and personal concerns expressed by our emigrating respondents which led them to question the prospect of returning.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

This was a large-scale national survey of two years of graduation cohorts of UK-trained doctors, surveyed at two time points in surveys which covered the period from 2004 to 2015. In all, 290 doctors who were working outside the UK responded. This was, however, a subset of all doctors from the two cohorts who were working abroad, and we do not know how the doctors working abroad who did not respond to our surveys would have replied to the survey questions. There is therefore a risk of non-responder bias.

Comparison with existing literature

We found that 91% of the 1993 and 1996 cohort respondents were working in the National Health Service 17/19 years after graduation. One of our earlier studies found that 85% of respondents from the 1988 UK cohort were working in the National Health Service 16 years after graduation.11

Similar studies have found that UK-trained doctors working in New Zealand are predominantly doing so for quality of life reasons.8,9 Our study probed beyond reasons for moving abroad and asked the doctors what might draw them back. This is why we found that doctors cited political, management, and pay issues as the most important changes needed to UK medicine. A survey of Irish-trained health professionals who had emigrated found that they did so because of poor working conditions in Ireland: we found that doctors in our study were also unhappy about working conditions within the UK National Health Service and wanted to see conditions improve before they would consider a return.12 A study from 2004 asked doctors who were considering leaving the UK what their reasons for leaving were: 65% cited lifestyle, 41% cited UK working conditions, and 18% cited ‘positive work-related’ reasons (e.g. a desire to work in a developing country).13

Implications/conclusions

Young doctors have often sought short periods of work outside their host countries in order to widen their experience and broaden their knowledge. The doctors in this study were established in their careers and had for the most part been outside the UK for a number of years. Many of them were settled in their adopted country and it would be more difficult to persuade them to return than others who have only been outside the UK for a short while. Nevertheless, policy attention to factors including funding, pay, management and particularly the clinical–political interface, working hours, and work–life balance may pay dividends for all, both in terms of persuading some to return and, perhaps more importantly, encouraging other, younger doctors to believe that the UK and the National Health Service can offer them a satisfying and rewarding career.

Acknowledgements

We thank Janet Justice and Alison Stockford for data entry. We are very grateful to all the doctors who participated in the surveys.

Declarations

Competing Interests

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and all authors want to declare: (1) financial support for the submitted work from the policy research programme, Department of Health. All authors also declare: (2) no financial relationships with commercial entities that might have an interest in the submitted work; (3) no spouses, partners, or children with relationships with commercial entities that might have an interest in the submitted work; (4) no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Funding

This is an independent report commissioned and funded by the Policy Research Programme in the Department of Health (project number 016/0118). The views expressed are not necessarily those of the funding bodies.

Ethical approval

National Research Ethics Service, following referral to the Brighton and Mid-Sussex Research Ethics Committee in its role as a multi-centre research ethics committee (ref 04/Q1907/48 amendment Am02 March 2015).

Guarantor

All authors are guarantors.

Contributorship

TWL and MJG designed and conducted the surveys. FS performed the analysis and wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors contributed to further drafts and all approved the final version.

Provenance

Not commissioned; peer-reviewed by Shelain Patel

References

- 1.Hunt J. Hunt: speech to conservative party conference, http://pressconservativescom/post/151337276050/hunt-speech-to-conservative-party-conference-2016 (15 Dec 2016, accessed).

- 2.Freer J. Is Hunt’s plan to expand medical student numbers more than a party conference pipe dream? BMJ 2016; 355: i5488–i5488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Foundation Programme. The Foundation Programme Annual Report 2016. Birmingham: The Foundation Programme, 2016.

- 4.Royal College of Physicians. Underfunded, underdoctored, overstretched: the NHS in 2016. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2016.

- 5.Kenny C. 5,000 doctors a year considering leaving the UK to emigrate abroad, http://wwwpulsetodaycouk/home/finance-and-practice-life-news/5000-doctors-a-year-considering-leaving-the-uk-to-emigrate-abroad/20007366article (15 Dec 2014, accessed).

- 6.Goldacre MJ, Davidson JM, Lambert TW. Retention in the British National Health Service of medical graduates trained in Britain: cohort studies. BMJ 2009; 338: 1430–1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mullan F. The metrics of the physician brain drain. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 1810–1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma A, Lambert TW, Goldacre MJ. Why UK-trained doctors leave the UK: cross-sectional survey of doctors in New Zealand. J R Soc Med 2012; 105: 25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gauld R, Horsburgh S. What motivates doctors to leave the UK NHS for a “life in the sun” in New Zealand; and, once there, why don’t they stay? Hum Resour Health 2015; 13: 75–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldacre M, Lambert T. Participation in medicine by graduates of medical schools in the United Kingdom up to 25 years post graduation: national cohort surveys. Acad Med 2013; 88: 699–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor K, Lambert T, Goldacre M. Career destinations, views and future plans of the UK medical qualifiers of 1988. J R Soc Med 2010; 103: 21–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Humphries N, McAleese S, Matthews A, Brugha R. ‘Emigration is a matter of self-preservation. The working conditions … are killing us slowly’: qualitative insights into health professional emigration from Ireland. Hum Resour Health 2015; 13: 35–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moss PJ, Lambert TW, Goldacre MJ, Lee P. Reasons for considering leaving UK medicine: questionnaire study of junior doctors’ comments. Br Med J 2004; 329: 1263–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]