Abstract

Objective

Clinical decision-making regarding the prevention of depression is complex for pregnant women with histories of depression and their healthcare providers. Pregnant women with histories of depression report preference for non-pharmacological care, but few evidence-based options exist. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy has strong evidence in the prevention of depressive relapse/recurrence among general populations and indications of promise as adapted for perinatal depression (MBCT-PD). With a pilot randomized clinical trial, our aim was to evaluate treatment acceptability and efficacy of MBCT-PD relative to treatment as usual (TAU).

Methods

Pregnant adult women with depression histories were recruited from obstetrics clinics at two sites and randomized to MBCT-PD (N= 43) or TAU (N=43). Treatment acceptability was measured by assessing completion of sessions, at-home practice, and satisfaction. Clinical outcomes were interview-based depression relapse/recurrence status and self-reported depressive symptoms through 6-months postpartum.

Results

Consistent with predictions, MBCT-PD for at-risk pregnant women was acceptable based on rates of completion of sessions and at-home practice assignments, and satisfaction with services was significantly higher for MBCT-PD than TAU. Moreover, at-risk women randomly assigned to MBCT-PD reported significantly improved depressive outcomes compared to participants receiving TAU, including significantly lower rates of depressive relapse/recurrence and lower depressive symptom severity during the course of the study.

Conclusions

MBCT-PD is an acceptable and clinically beneficial program for pregnant women with histories of depression; teaching the skills and practices of mindfulness meditation and cognitive behavioral therapy during pregnancy may help to reduce the risk of depression during an important transition in women’s lives.

Public Health Significance Statement

This study’s findings support MBCT-PD as a viable non-pharmacological approach to preventing depressive relapse/recurrence among pregnant women with histories of depression.

Keywords: pregnancy, depression, prevention, mindfulness, cognitive behavioral therapy

The adverse impact of depression during pregnancy and postpartum on both mother and offspring is well documented (Stein et al., 2014). Despite this context, limited options exist for preventing depression among pregnant and postpartum women. Women and their healthcare providers face challenging clinical decisions in the management of depression, as they must weigh potential benefits and costs for both the woman and the developing fetus (Patel & Wisner, 2011; Wisner et al., 2000; Yonkers, Lockwood, & Wisner, 2010). For a woman who enters pregnancy with a history of depression, the importance of such decision-making is underscored by the increased risk that she faces for depressive relapse/recurrence during the perinatal period. Specifically, evidence suggests that approximately 30–40% of pregnant women with histories of major depression will experience relapse during the perinatal period (Di Florio et al., 2013; S. H. Goodman & Tully, 2009). These estimates exceed prevalence rates from meta-analyses among unselected populations, which indicate approximately 15% of women experience the onset of a major or minor depressive episode during the perinatal period (Gavin et al., 2005).

One widely used option for prevention of depression recurrence/relapse in pregnant women is pharmacotherapy; current estimates suggest that over 7% of pregnant women overall use antidepressant medication (Yonkers, Blackwell, Glover, & Forray, 2014) and at least 75% of women identified as depressed are referred for pharmacotherapy (Dietz et al., 2007). Among women treated with antidepressants, rates of discontinuation during pregnancy and subsequent relapse/recurrence are high, with over 50% discontinuing and nearly 70% relapsing following discontinuation (Cohen et al., 2006; Roca et al., 2013). Such findings are consistent with survey research indicating that pregnant women prefer non-pharmacological approaches to prevention if provided the option (Dimidjian & Goodman, 2014). Scarcity of evidence for psychosocial preventive approaches, however, often leaves pregnant women and their care providers facing the choice between no intervention or pharmacotherapy to prevent future episodes of depression. This study aimed to address the need of pregnant women and care providers for a wider array of evidence-based options to prevent depression relapse/recurrence during the perinatal period.

Our earlier work focused on the development of an intervention for this purpose and population. We adapted one of the most widely studied preventive interventions for depression relapse/recurrence among the general population, Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) (Segal, Williams, and Teasdale, 2002), to be specific to the developmental processes associated with the perinatal period, correlates of perinatal depression, and the physical aspects of pregnancy (Mindfulness Based Cognitive for Perinatal Depression; MBCT-PD). We selected MBCT as the source intervention for three reasons: (a) it has strong empirical support in both relapse/recurrence prevention and reduction of residual depressive symptoms among adults with histories of depression Chiesa & Serretti, 2011; Piet & Hougaard, 2011); (b) it specifically targets the most robust risk factor for depression onset among perinatal women–history of depression (Beck, 2001; O’Hara & Swain, 1996); and (c) it aims to modify the type of depressive cognitive styles that have been associated with offspring vulnerability to depression (Pearson et al., 2013). MBCT achieves these aims through the unique integration of mindfulness meditation practices and cognitive-behavioral therapy strategies. MBCT is based on the theory that individuals with histories of depression are vulnerable during times of stress or challenge because associations between emotion and cognition present during prior depressive episodes are reactivated; these automatic, reactive processes increase risk for depressive relapse (Segal et al., 2006; Teasdale et al., 2002). Mindfulness meditation practices are taught to increase awareness of such automatic associations and to provide an alternate mode of relating to experience that is present-focused, decentered, accepting, and non-judgmental (van der Velden et al., 2015). Cognitive-behavioral strategies provide a context for understanding the nature of depression and for taking action in response to vulnerabilities.

Our open trial was the first investigation of MBCT focused specifically on pregnant women with histories of depression (Dimidjian et al., 2015). We found that MBCT-PD was associated with high interest, engagement with both in-session and at-home practice, and satisfaction, as well as reduced depressive symptoms during the 8-week class, which was sustained throughout the remainder of pregnancy and 6-months postpartum. These findings are convergent with an emerging evidence base that suggests that mindfulness-based interventions are promising for pregnant women, including those with elevated anxiety symptoms (J. H. Goodman et al., 2014) and those with broadly defined concerns about depression, anxiety, or stress (Dunn, Hanieh, Roberts, & Powrie, 2012; Vieten & Astin, 2008; Woolhouse, Mercuri, Judd, & Brown, 2014).

We conducted a two-site pilot randomized clinical trial with pregnant women at risk of depressive relapse/recurrence to investigate the acceptability of MBCT-PD and to compare the efficacy of MBCT-PD to treatment as usual (TAU) in the prevention of depressive relapse/recurrence. Within obstetric clinical settings at Kaiser Permanente (KP) in Colorado and Georgia, we randomly assigned 86 pregnant women with histories of major depression to MBCT-PD or TAU. We predicted that MBCT-PD would be acceptable based on completion of sessions and at home practice assignments, and that it would be associated with significantly greater satisfaction than TAU. We also predicted that women randomly assigned to MBCT-PD would report significantly improved depressive outcomes compared with those receiving TAU, including lower rates of depressive relapse/recurrence and lower depressive symptom severity during the course of the study.

Method

Participants and Procedures

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards and through institutional agreement at the University of Colorado Boulder, Emory University, Kaiser Permanente Colorado (KPCO) and Kaiser Permanente Georgia (KPGA), and all participants provided written informed consent. We recruited participants between 2010 and 2013 through liaison with obstetrics clinics at KPCO and KPGA. Potential participants were notified about the study through their providers, typically as a result of routine screening for past depression during initial pregnancy visits. Initial eligibility criteria (e.g., age, past and current depression, and gestational age) were assessed via phone screen and final eligibility was determined during an in-person baseline interview.

Primary inclusion criteria included: (a) pregnant women up to 32 weeks gestation, (b) meeting criteria for prior major depressive disorder (MDD), (c) available for group intervention scheduled meetings, and (d) aged 18 or older. Exclusion criteria include a diagnosis of MDD in the last two months (given the focus on prevention, not acute intervention) and any other Axis I or II psychiatric disorders that necessitated priority, non-study intervention (e.g., schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or current psychosis; organic mental disorder or pervasive developmental delay; current eating disorder; current substance abuse or dependence; antisocial, borderline, or schizotypal personality disorder, and imminent suicide or homicide risk). Furthermore, participants were excluded for high-risk pregnancy status, which was operationalized in collaboration with our obstetric partners in the KP clinical settings and was determined by obstetrician report (e.g., pre-term labor, placental abnormality, multiple gestations, required bed rest, or morbid obesity). There were no limitations in either study condition on receiving non-study treatment, including psychotropic medications or psychotherapy. Any participants, in either condition, who reported clinically significant depressive symptoms were referred for additional behavioral health services at KPCO or KPGA via the study clinical liaisons.

Over the course of the study, a total of 12 cohorts were recruited (six at each site). Initial intake assessments were conducted at KP facilities, with later assessments conducted at KP facilities, in participants’ homes, by phone, or online format using a password protected secure survey website. Participants were compensated $115 for completing assessments. This amount was increased for women with transportation or childcare expenses in order to enable participation. We also sent a nominal gift after the birth of each participant’s baby.

Measures

Baseline diagnostic status was evaluated using the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition-Text Revised (SCID-I/P; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002) to assess psychiatric diagnoses and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II; First, Miriam, Spitzer, Williams, & Lorna, 1997) to assess the presence of exclusionary personality disorders. Trained bachelor’s and master’s level clinical evaluators administered both the SCID-I/P and II and randomly selected interviews (n = 11) were assessed for inter-rater reliability of current and past major depressive episode, indicating a perfect level of inter-rater agreement.

Acceptability of MBCT-PD was operationalized in two ways: class attendance and completion of assigned at-home practice. Consistent with prior MBCT studies, we defined completion as having attended four or more of the eight MBCT-PD sessions. At-home practice was assigned for 6 days each week between Sessions 1 and 7 (42 total days) and completion was assessed using daily written reports on which participants recorded the number of times and type of practice (e.g., formal, informal).

Participant satisfaction was assessed using the 8-item self-report Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (Attkisson & Zwick, 1982) at the 8-week assessment and at 6 months postpartum to measure women’s satisfaction with their study condition. Yielding a homogeneous estimate of general satisfaction with services, scores range from 8 to 32, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction (Cronbach’s alpha was .94 at 8-weeks and .93 at 6 months postpartum).

Depression relapse/recurrence as assessed using the Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation (LIFE; Keller et al., 1987), a semi-structured interview, consistent with DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria (APA, 2000), at 8-weeks, 1 month prior to delivery, and 1 and 6 months postpartum to assess relapse/recurrence status postintervention. The LIFE provides psychiatric status ratings (PSRs) obtained retrospectively for each study week since the previous interview, ranging from 1 (absence of symptoms) to 6 (definite and severe presence of symptoms), with relapse/recurrence defined as at least 2 weeks of ratings of 5 or greater. Bachelor’s or master’s level research assistants, all blind to intervention condition, were trained and certified to conduct these interviews and were supervised weekly to prevent drift in ratings. Another evaluator or study investigator reviewed interviews indicating relapse/recurrence; in cases of disagreement, consensus was achieved through discussion and these consensus ratings were used for analysis. An additional subset of interviews was selected randomly for reliability checks on depressive relapse/recurrence status (n = 12), indicating agreement on 92% of cases.

Depression symptom severity was assessed using the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS), which is the most commonly used self-report severity measure and has strong psychometric properties among both pregnant and postpartum samples (Cox, Holden, & Sagovsky, 1987; Murray & Carothers, 1990). Total scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating greater severity. For both intervention conditions, the EPDS was administered at intake, at baseline immediately before randomization, mid- and postintervention (and comparable times for the TAU), at each session for participants receiving MBCT-PD, and monthly during the remainder of pregnancy and through six months postpartum. Scores acquired at the following time points (and corresponding αs) are included in the current report: intake (0.83), baseline (0.87), postintervention for MBCT-PD or the comparable time for TAU (0.83), and 1 and 6 months postpartum (0.90 and 0.89, respectively).

MBCT-PD Instructor Adherence

Adherence to the protocol was rated using the MBCT Adherence Scale (Segal, Teasdale, Williams, & Gemar, 2002), adapted for MBCT-PD (MBCT-PD-AS). Thirteen items measure the presence of clinical strategies rated on a 3-point scale of 0 (no evidence), 1 (slight evidence), or 2 (definite evidence), and a mean score of greater than 1 indicates adequate adherence. Trained raters (one doctoral student and one master’s level research assistant), both blind to intervention outcome, rated one session in the early phase of therapy (Session 2) and one later session (Session 6) for all cohorts in order to assess thematically distinct samples of the intervention in a standardized manner. Interrater reliability was determined by calculating intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for a random 29% of the sessions (n=14), treating the raters as random effects, with results indicating high interrater reliability (ICC = 0.86).

Service Utilization

In order to characterize the nature of usual care, data were extracted from mental health related pharmacy, diagnosis, and procedure codes from a virtual data warehouse that is populated with electronic medical records data at KPCO and KPGA. Data extraction focused specifically on psychotropic medication dispensing and psychotherapy during the study period.

Treatment

MBCT-PD

The 8-session protocol for MBCT was based on the standard MBCT treatment manual and theory that proposes that individuals with histories of depression are vulnerable during dysphoric states, during which maladaptive patterns present during previous episodes are reactivated and can trigger the onset of a new episode (Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2002). Formal and informal mindfulness practice and cognitive behavioral skills are taught to help participants cultivate mindful rather than automatic, depressogenic modes of relating to thoughts, emotions, and sensations. The standard MBCT protocol was modified for use in the context of pregnancy and in anticipation of the postpartum. Modifications included stronger emphasis on brief informal mindfulness practices, given our developmental work that suggested that barriers of time, energy, and fatigue are significant among pregnant women, and perinatal specific practices. We included lovingkindness meditation practice based on our developmental work suggesting that self-criticism is a common theme among at risk pregnant and postpartum women and that connection with one’s child is a powerful motivator for learning and practice. Lovingkindness meditation practice asks women to direct awareness and intention at both the self and the baby through the repetition of specific phrases (e.g. “May I/my baby be filled with lovingkindness. May I treat myself/my baby with kindness in good times and in hard times. May I/my baby be well and live with ease.”). We also included psychoeducation about perinatal depression, anxiety, and worry, which are often co-occurring with depression among perinatal women, and the transition to parenthood. We also included an emphasis on self-care practices and cognitive-behavioral strategies to enhance social support. For example, women were guided to identify specific actions to enhance well-being during the postpartum period (e.g., reduced responsibility for family meals), to observe and decenter from self-judgments that may interfere with such actions (e.g., “good mothers can handle a new baby and making dinner”), and to role play asking for support from friends or family to carry out the specified actions. At each session, participants were given audio-recorded files to guide mindfulness meditation practices at home (recorded for the study by expert meditation teacher Sharon Salzberg) and a DVD was provided to guide yoga practice (recorded for the study by expert perinatal yoga teacher De West). Table 1 describes the sequence of session topics, targets, and at-home practice assignments.

Table 1.

MBCT-PD Protocol

| Session | Topics | In-Session Targets | Assigned At-Home Practices |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Doing mom / being mom | Enhancing motivation, developing group cohesion and trust, and promoting awareness of automatic pilot and “doing mom” mode and cultivating “being mom” mode. In addition, connections are highlighted between an automatic reliance on “doing mom” and vulnerability to depressive relapse/recurrence. | Body scan, daily mindfulness practice (eating, drinking, and washing dishes), catching “automatic pilot,” identifying and connecting with the support person. |

| 2 | Responding to barriers | Skillfully responding to common challenges that pregnant and postpartum women experience with integrating mindfulness into their daily lives and stepping out of automatic modes of doing (and overdoing), including guilt and self-criticism. A key skill highlighted is being gentle and kind with oneself. | Body scan, breath focused meditation, daily mindfulness practice, pleasant events noticing, and connecting with the support person. |

| 3 | Mindful breathing and movement | Strengthening the skills of mindfulness in the context of extended formal sitting (breath focused meditation) and movement (walking meditation and yoga) practices as well as the 3-minute breathing space and an expansion of the daily informal practice to include mindfully “being with baby.” | Sitting meditation, yoga practice, 3-minute breathing space (daily), “being with baby,” unpleasant events noticing, and connecting with the support person. |

| 4 | Opening to difficulty and uncertainty | Responding to difficulty and uncertainty as they arise during pregnancy and postpartum in ways that reduce risk for depression, anxiety, and stress. Specifically, the session focuses on increasing awareness of thoughts, emotions, and sensations rather than engaging automatic patterns of fighting against them, wanting them to be other than they are, or adding onto them with additional negative thinking. Toward this end, another target includes increased understanding and awareness of the signs and symptoms of depression and anxiety during pregnancy and common “depression thoughts” and “pregnancy worries.” | Sitting meditation, yoga practice, 3-minute breathing space (daily), 3-minute breathing space (with difficulties), daily informal practice including “being with baby,” and connecting with the support person. |

| 5 | Thoughts are not facts | Developing a wider, decentered perspective on difficult thoughts and images, through recognizing patterns of thoughts that tend to recur, particularly negative, self-critical, judgmental thoughts, and shifting from being caught up in or identified with one’s thoughts to seeing thoughts as mental events, not necessarily valid truths about the world or the self. | Sitting meditation, yoga practice, the daily 3-minute breathing space, the coping 3-minute breathing space, “Whoosh? Noticing thoughts that carry you away,” daily informal practice including “being with baby,” and connecting with one’s support person. |

| 6 | How can I best care for myself? | Increased self-care as a natural and important part of daily life and critical step in preventing relapse, focusing on the use of non-judgmental attention during all meditation practices, the use of lovingkindness meditation in particular, mindful awareness to daily activities and the influence of such activities on mood, and awareness of relapse signatures. | Lovingkindness meditation, 3-minute breathing space (daily and coping), activity scheduling and structuring, draft letter to oneself, daily mindfulness practice including “being with baby,” and connecting with the support person. |

| 7 | Expanding circles of care | Interpersonal relationships, social support, beliefs that interfere with accessing social support, and specific skills of asking for help and saying no to requests that are not in one’s best interest. These targets are highlighted in the context of the demands for self- and other-care during late pregnancy and the postpartum. The importance of reaching out to others to support wellness and prevent relapse is addressed through exploring how easy or difficult is it to ask other people for help, and beliefs and emotions that function as barriers to asking for help. | Personal choice practice to integrate into daily life, informal daily practice, 3-minute breathing spaces, expanding the circle of care, and revising the “staying well” letter and sharing it with the support person. |

| 8 | Looking to the future | Building bridges from the structured 8-session program to the future, consolidating relapse prevention plans; reinforcing links between mindfulness practices and prevention of depression during the remainder of pregnancy and postpartum. |

The eight-session series included class sizes ranging from three to nine assigned participants. We allowed groups to be conducted with fewer women than has been reported in prior studies of MBCT in the general population for pragmatic reasons given the narrow window within which preventive intervention can occur during pregnancy for at risk women. We also permitted participants to complete make-up sessions by phone. Sessions were approximately 2 hr in length and held weekly. Following the 8 sessions, participants were given the option of attending a monthly follow up class. One of the two study investigators (SD; SHG, both licensed clinical psychologists with PhDs trained by one of the MBCT founders) and a KP behavioral health provider co-led the sessions. The majority of providers had completed a 5-day residential intensive training program in MBCT. The study therapists met weekly during the intervention to discuss the clinical delivery of MBCT-PD. The mean score on the modified MBCT Adherence Scale (MBCT-PD-AS) was 1.45 (SD = 0.17), indicating above adequate instructor adherence to the protocol.

Treatment as usual

TAU participants were free to continue or initiate mental health care (as were those in the MBCT-PD condition). In addition, we notified participants by telephone or in person at the time of assessment when their depressive symptom levels were elevated. We also assisted with referrals to behavioral health care in the KP systems.

Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted with the intent-to-treat sample. We compared differences by condition on baseline demographic and clinical characteristics using t-tests and χ2 tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. The requirement that continuous measures be approximately normally distributed was met by all variables with the exception of age, which exhibited a slight negative skew requiring a square transformation to correct this deviation in normality. Given a marginal difference between groups on age, t(84)=−1.94, p=.06, where on-average MBCT-PD participants were slightly older than TAU, the transformed value of age was included as a covariate in all models. With respect to site, at baseline, a greater proportion of the sample was White relative to non-White in Colorado (85%) as compared to Georgia (50%), χ2(1) = 11.95, p = .001, and was married or cohabiting in Colorado (96%) as compared to Georgia (74%), χ2(1) = 8.98, p = .003. Participants in Colorado also were significantly more likely to have histories of anxiety disorders (54%) and three or more prior episodes of depression (36%) than those in Georgia (26% and 9%, respectively), χ2(1) = 6.28, p = .012 and χ2(1) = 8.30, p = .004, respectively. Given these differences, we adjusted for site in all outcome analyses. All other baseline characteristics were not statistically significantly different between sites and were small in magnitude (d < 0.39).

To address our hypotheses regarding acceptability, we computed the mean number of completed classes and at-home practices. We used an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to test our hypothesized group differences in self-reported satisfaction, separately at 8 weeks and the study endpoint. We examined differences between groups in mental health service utilization using χ2 tests.

We examined differences between conditions in relapse/recurrence using Cox regression proportional hazard survival analysis, which are standard for modeling time processes. Time to attrition is considered a competing risk that can be related to time to relapse. While standard Cox regression models can accommodate competing risks discussed in Gooley, Leisenring, Crowley, and Storer (1999), we adopted the subdistribution hazard model extension of the Cox model developed by Fine and Gray (1999) and discussed in Szychowski, Roth, Clay, and Mittelman (2010), to account for the possible nonindependence between attrition and relapse mechanism. Survival analyses classify participants who do not achieve the event of interest as censored. In this competing risk structure, participants who complete the observation period without relapse are classified as censored. Participants who drop out are classified as nonrelapse events in the competing risk group. The weighted partial likelihood estimation within the subdistribution hazard model directly assesses the intervention in the presence of a competing and possibly informative relationship between attrition, relapse, and completion without relapse. Given the course of relapse/recurrence over time, in which an abrupt increase in rates was observed in the postpartum, we also used an extended Cox Regression model, considering periods of time of pregnancy and postpartum, where the failure rate (i.e. relapse rate) may suddenly increase or decrease. The extent to which treatment differences in relapse differed by site was assessed by including a site by treatment interaction in the survival analyses.

We examined depressive symptom severity using a mixed model analysis of variance (MMANOVA). The MMANOVA framework allowed us to accommodate the clustering because of repeated measures within a subject and missing data; moreover, because the MMANOVA treats time as a categorical factor, therefore estimating means for each group for each time point, hence it accommodates nonlinear change over time. The MMANOVA model allowed us to assess differences in change in EPDS scores within intervention arms as well as between arms using linear contrasts of interest; specifically, we examined estimates, controlling for intake scores, of the change from baseline to the postintervention assessment (or the comparable period of time for the TAU participants) in order to examine the effect of the intervention, as well as of the change from baseline through the entire post-baseline period in order to examine any intervention effect over the entire study period. The MMANOVA framework requires multivariate normality of the model based residuals, and the Box-Cox (Box & Cox, 1964) assessment indicated the need to employ a square-root transformation on the EPDS outcome to ensure normality of the residuals at each discrete time point, resulting in multivariate normality. The extent to which treatment differences in depressive symptoms differed by site was assessed by including a site by treatment interaction in the MMANOVA analyses.

Power was initially calculated for the contrast between MBCT-PD and TAU for our relapse/recurrence outcome. Based on prior studies of MBCT suggesting overall relapse/recurrence rates of 39.50% in MBCT and 63.50% in TAU and attrition of approximately 10% in MBCT (Ma & Teasdale, 2004; Teasdale et al., 2000; Williams, Teasdale, Segal, & Soulsby, 2000), we estimated that n=160 (80 per group), α = .05, 2-tailed, would provide 0.82 power, with attrition of 10%, and .80 power, with attrition of 15%. Based on our observed sample (n=86), with an observed attrition rate of 19.8% through the follow-up phase, we had the power of 71.4% and 81.4% for a two-tailed and one-tailed test, respectively, and a 30% difference in relapse rate provided 84.3% power.

Results

Participant Enrollment and Flow

We conducted phone screens with women who were referred and indicated interest in the study to determine initial eligibility (n = 377). Of these, 68 women (18%) declined participation and 200 women (53%) failed the phone screen, with current MDD as the most frequent reason for ineligibility (n = 77). Of the remaining 109 women with whom we conducted in person intakes to assess eligibility, the most frequent reason for ineligibility was current major depression (n = 5), followed by late gestational age (n = 3), no history of MDD (n = 2) and other (n = 3). Women declined for the following reasons: concerns about time (n = 1), lack of interest (n = 2), and unknown (n = 7). A total of 86 participants were randomized in cohorts to MBCT-PD (n = 43) and TAU (n = 43).

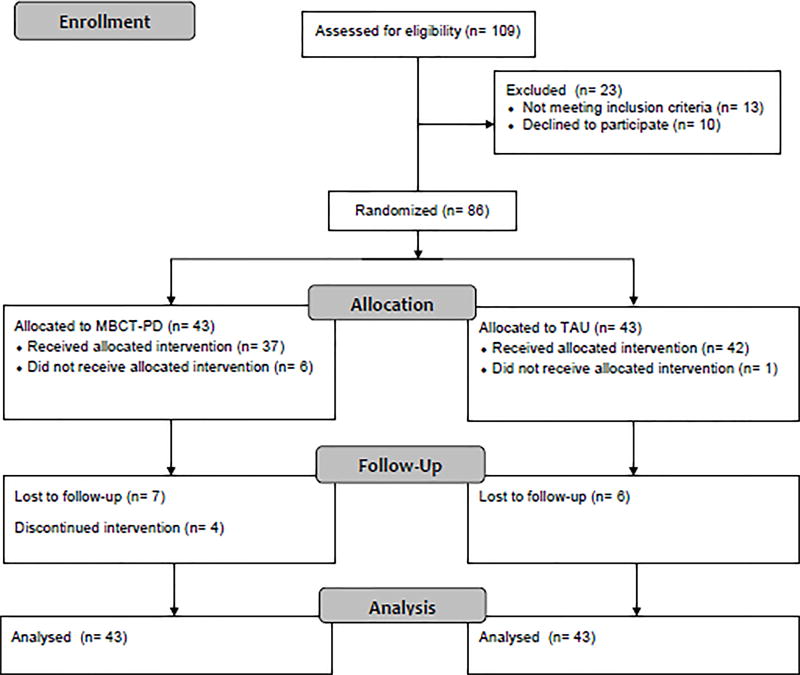

Figure 1 illustrates participant flow during the study using the CONSORT diagram. Among participants assigned to MBCT-PD, six discontinued during allocation; of these, two participants did not provide reasons, three reported time commitment or childcare problems, and one delivered before the first class. Among participants assigned to TAU, one participant discontinued during allocation because of dissatisfaction with her treatment assignment. Following allocation, within MBCT-PD, 7 additional participants were lost to follow up; three participants stated lack of time, three did not provide reasons, and one was withdrawn because of miscarriage. Within TAU, six additional participants were lost to follow up; two participants stated lack of time, two did not provide reasons, one was withdrawn because of miscarriage, and one was withdrawn because of acute depression.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram. MBCT-PD = Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy for Perinatal Depression; TAU = Treatment as Usual.

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for the sample. The majority of participants were married or cohabiting and nearly half were pregnant with a first child. The majority of participants also were White, and 18.60% (n = 16) were African American, 2.32% (n = 2) were Asian, 6.98% (n = 6) were Hispanic, and 1.12% (n = 1) self-identified as Other. No significant differences between conditions were observed, with the exception of the marginally significant difference on age.

Table 2.

Participant Baseline Characteristics

| Participant Characteristic | MBCT-PD (N= 43) |

TAU (N= 43) |

Test statistic | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age: M (SD) | 30.98 (4.08) | 28.72 (5.50) | t(83) = 1.94 | 0.06 |

| Week of gestational age at enrollment: M (SD) | 15.29 (5.85) | 16.65 (6.15) | t(83) = 1.05 | 0.30 |

| Ethnicity/Race: n (%) White | 33 (76.74) | 28 (65.12) | χ2(1) = 1.41 | 0.23 |

| Married or cohabiting: n (%) | 38 (88.37) | 35 (81.40) | χ2(1) = 0.82 | 0.37 |

| Primiparous: n (%) | 22 (51.16) | 20 (46.51) | χ2(1) = 0.19 | 0.67 |

| Income ≥ $50,000: n (%) | 20 (46.51) | 23 (53.49) | χ2(1) = 0.58 | 0.45 |

| College graduate: n (%) | 36 (83.72) | 30 (69.77) | χ2(1) = 2.35 | 0.13 |

| Past major depressive episodes: n (%) | χ2(2) = 2.6952 | 0.26 | ||

| One | 15 (34.88) | 15 (34.88) | ||

| Two | 14 (32.56) | 20 (46.51) | ||

| Three or more | 14 (32.56) | 8 (18.60) | ||

| Any current or lifetime anxiety disorder | 15 (34.88) | 22 (51.16) | χ2(1) = 2.32 | 0.13 |

| Any lifetime alcohol or substance abuse or dependence | 19 (44.19) | 14 (32.56) | χ2(1) = 1.23 | 0.27 |

Note. MBCT-PD = Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy for Perinatal Depression; TAU = Treatment as Usual.

MBCT-PD Acceptability and Satisfaction

Of the 37 participants who started MBCT-PD, 33 (89%) completed the intervention (as defined by attending at least 4 sessions), with an average of 6.89 (SD = 2.04) sessions completed. Of those who did not complete, two reported time commitment and reasons are unknown for two. With respect to engagement with the MBCT-PD practices, among participants who started MBCT-PD, 29 participants (67%) reported practice data. Of those reporting practice data, participants engaged frequently in at-home practices, reporting, on average, at least some practice on 30 (SD = 11.85) out of the 42 assigned days, with a higher total frequency of informal mindfulness practices, M = 82.17, SD = 55.71, than formal practices, M = 25.03, SD = 10.74.

Participants assigned to MBCT-PD reported a high degree of satisfaction on the CSQ-8 at the end of the intervention, M = 29.17, SD =3.28, and at the study endpoint, M =28.95, SD =3.50. As assessed through ANCOVA adjusted for age and site, level of satisfaction associated with MBCT-PD was significantly higher than that reported by participants assigned to TAU, M = 21.76, SD = 5.44, t(48)=−5.66, p < .0001, d = 1.59 at 8 weeks and M = 21.97, SD = 5.05 at study endpoint, t(45)=−5.39, p < .0001, d = 1.56.

Depressive Relapse/Recurrence and Severity

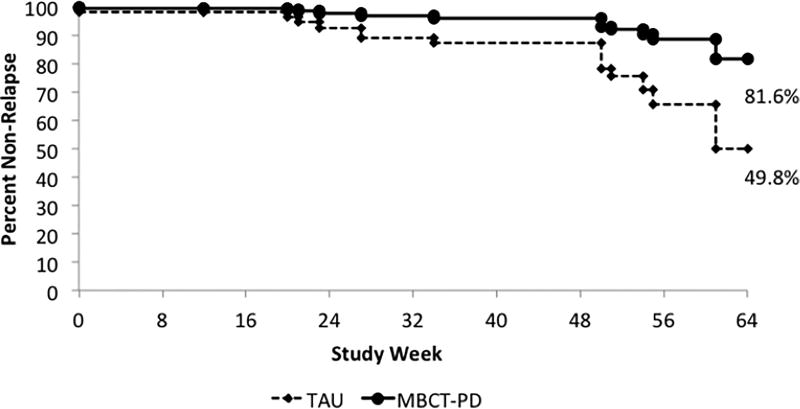

Survival analysis, fit through the Cox-model adjusted for site and age, was used to examine rates of relapse/recurrence. As illustrated in Figure 2, MBCT-PD demonstrated a significant prophylactic effect relative to TAU, χ2(1) = 6.92, p = .008, over the entire study period; estimated rates of relapse were 18.4% for MBCT-PD and 50.2% for TAU. The hazard ratio (HR = 3.87, 95% CIs [1.39–10.76]) indicated that the rate of relapse for MBCT-PD was 74% less than for TAU during the entire study period. Given the observed course of relapse/recurrence, we also examined the extended Cox Regression model. During pregnancy, between enrollment and giving birth, there was a non-significant difference in time to relapse between MBCT-PD and TAU, χ2(1) = 0.62, p = .43; however, in the postpartum period, there was a significant difference in the rate of relapse/recurrence between MBCT-PD and TAU, χ2(1) = 7.85, p = .005. During the postpartum, rates of relapse were 4.6% (1/22) for MBCT-PD and 34.6% (9/26) for TAU, and MBCT-PD was associated with a hazard ratio of 0.12 (95% CIs, [0.015–0.912]), indicating that MBCT-PD reduced risk by 88% compared to TAU during the postpartum period. The extent to which treatment differences in relapse differed by site was assessed by including a treatment by site interaction in the survival analyses, which was nonsignificant when considering the entire study period, χ2(1) = 1.33, p = .25, during pregnancy, χ2(1) = 1.09, p = .30, and during the postpartum period, χ2(1) = 0.0001, p = .99.

Figure 2.

Time to relapse/recurrence by condition. Model estimated rates adjust for site, age, and censoring, where censored patients are not counted in either the relapse or total. Median time to birth for study participants was study week 26. TAU = Treatment as Usual; MBCT-PD = Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy for Perinatal Depression.

Consistent with our hypothesis, participants in MBCT-PD reported, on average, significantly lower levels of depressive severity than participants in TAU (see Table 3). During the intervention period, there was a significant difference between groups at the postintervention assessment, t(83) = 3.19, p = .002, d = 0.70, with participants assigned to MBCT-PD reporting significant reduction in average severity relative to baseline, t(83) = 2.04, p = .043, d = 0.44, and those assigned to TAU reporting significant increase in average severity relative to baseline, t(83) = −2.48, p = .014, d = 0.54. Considering the entire postbaseline period, MBCT-PD was associated with significantly lower on average depression severity as compared to TAU, t(83) = 3.31, p = .002, d = 0.720; within MBCT-PD, there was a nonsignificant reduction in average severity relative to baseline, t(83) = 1.66, p = .099, d = 0.38, whereas within TAU, there was a significant increase in average severity relative to baseline, t(83) = −3.01, p = .003, d = 0.66. The extent to which treatment differences in depressive severity differed by site was assessed by including a site by treatment interaction in the MMANOVA analyses, which was not significant during the intervention period, F(1,77) = 3.52, p = .051, d = 0.428, and the full study period, F(1,77) = 4.02, p = .15, d = 0.457.

Table 3.

Depressive Symptom Severity (EPDS) by Condition by Time

| MBCT-PD

|

TAU

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | n | M | SD | n | |

| Baseline | 5.98 | 3.95 | 40 | 5.07 | 4.91 | 43 |

| Post-intervention | 4.67 | 9.95 | 24 | 6.39 | 3.81 | 31 |

| 1 month post-partum | 5.48 | 5.54 | 21 | 7.13 | 4.90 | 31 |

| 6 month post-partum | 4.90 | 5.22 | 21 | 6.62 | 4.94 | 29 |

Note. EPDS = Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, TAU = Treatment as Usual; MBCT-PD = Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy for Perinatal Depression.

Mental Health Service Utilization

Pharmacy dispensing data were available for 79/86 (91.9%) participants, and psychotherapy data were available for 78/86 (90.7%) participants between randomization and 6 months postpartum. Among these participants, 15.4% (n = 6) assigned to MBCT-PD and 27.5% (n = 11) assigned to TAU were dispensed psychotropic medication. With respect to psychotherapy, 13.2% (n = 5) assigned to MBCT-PD and 10.0% (n = 4) assigned to TAU had two or more psychotherapy visits. Differences between groups were not significant for pharmacy dispensing, χ2(1) = 6.89, p = .66, or psychotherapy visits, χ2(1) = 1.72, p = .19.

Discussion

Our findings from this pilot randomized clinical trial provide evidence that the return of depression can be prevented among at-risk pregnant women. We examined the use of the preventive MBCT-PD intervention among pregnant women with histories of depression and compared their outcomes to women who received only TAU in a large healthcare maintenance organization. We found significantly lower rates of relapse/recurrence and depressive symptoms through 6 months postpartum among women who received MBCT-PD relative to TAU. Given that depression during pregnancy and the postpartum has adverse and potentially enduring correlates and consequences for women and their children (S. H. Goodman et al., 2011; Stein et al., 2014), the value of helping at-risk pregnant women prevent depression is clear.

This relapse prevention effect was substantial, with an estimated rate of 18.4% of women who received MBCT relapsing over the six months postpartum, in contrast to 50.2% of women who received TAU. Overall, women who received MBCT-PD experienced approximately 75% reduction in hazard ratio for relapse/recurrence as compared to TAU. Analyses that focused specifically on the postpartum period revealed that this protective effect was evident primarily in the postpartum, which was the window of greatest risk in this study. It does not appear that this finding can be explained by an unusually high rate of depression among women who received TAU given reported relapse rates of 30% in a prospective naturalistic study (S. H. Goodman & Tully, 2009). Within the context of treatment studies with perinatal women, rates of relapse and recurrence among placebo and care as usual controls also are in line with the results from our trial. In two studies of prophylactic use of antidepressant medication after delivery among women with histories of postpartum depression who were randomly assigned to a placebo intervention, 24% experienced recurrence during a 20-week study period (Wisner et al., 2001), and 50% experienced recurrence of depression during a 17-week study period in another trial (Wisner et al., 2004). In two studies of preventive interpersonal psychotherapy, financially disadvantaged at-risk women assigned to treatment as usual reported relapse rates of 20–30% (Zlotnick, Johnson, Miller, Pearlstein, & Howard, 2001; Zlotnick, Miller, Pearlstein, Howard, & Sweeney, 2006). Furthermore, rates of mental health service utilization suggest that the benefit of MBCT-PD was not explained by disproportionate use of other services among women in that condition; there were no significant differences in pharmacy dispensing or psychotherapy visits between MBCT-PD and TAU.

In addition to the prevention of relapse/recurrence, the indications of lower depressive symptoms among women in MBCT-PD compared to TAU during pregnancy and postpartum is important given data suggesting that depressive symptoms are associated with adverse correlates and consequences for mothers and offspring, even when below diagnostic thresholds (S. H. Goodman et al., 2011; S. H. Goodman & Tully, 2009). Although these data are limited to providing a “snapshot” of women’s symptoms at distinct time points during the follow-up period, they are convergent with other studies of cognitive behavioral therapy preventive interventions during pregnancy, suggesting that nonpharmacological approaches are viable options for reducing residual depressive symptom levels during this important life transition (Le, Perry, & Stuart, 2011; Tandon, Perry, Mendelson, Kemp, & Leis, 2011).

Women of childbearing age represent the largest demographic group at risk of depression, and antidepressants are frequently used to manage depression during pregnancy (Yonkers et al., 2014). However, the majority of women who are treated with antidepressant medication discontinue use early in pregnancy and experience high rates of relapse/recurrence (Cohen et al., 2006; Roca et al., 2013). In an early study of pharmacological prophylactic treatment using an SSRI, Wisner and colleagues concluded that the medication “prevented the expression of postpartum-onset major depression, but the vulnerability to depression was manifest after the drug was withdrawn” (Wisner et al. 2004, p. 1291). Moreover, even those women who maintain antidepressants during pregnancy do not experience absolute protection—24% of these women experienced recurrence in a prospective study (Cohen et al., 2006). In contrast to pharmacotherapy, the prevention effects of MBCT-PD appear to be enduring, conferring benefit after women have completed the 8-session class series. Important questions for future research are the extent to which MBCT may be useful for women as an alternative to or augmentation for pharmacological treatment to provide protection during discontinuation or to minimize partial or non-response to pharmacotherapy.

Our findings also indicate that MBCT-PD not only evidences clinical benefit but also acceptability among at-risk pregnant women. Consistent with our open trial, pregnant women with histories of depression reported high satisfaction and engagement with the MBCT-PD intervention (Dimidjian et al., 2015). Participants in MBCT-PD rated their satisfaction significantly higher than those in TAU, and this was a large effect both at the end of the intervention phase and study endpoint. Nearly 90% of those who began the MBCT-PD classes completed at least four sessions (and on average, 7 of the 8 sessions). Women receiving MBCT-PD also reported engaging in at-home practice on approximately 70% of days.

The evidence of the acceptability of MBCT-PD is convergent with an emerging literature on the use of mindfulness during pregnancy to support mental health (Dunn et al., 2012; J. H. Goodman et al., 2014; Vieten & Astin, 2008; Woolhouse et al., 2014) and parenting (Duncan & Bardacke, 2010). The development and delivery of the MBCT-PD intervention in obstetric clinics also speaks to the potential scalability of this approach. The development of MBCT-PD was informed by women’s reports of preferences for care delivery (Dimidjian & Goodman, 2014; S. H. Goodman, Dimidjian, & Williams, 2013), with specific attention to implementation in routine care settings. It may be that approaches like MBCT are less likely to engender stigma because women associate it with prevention-oriented, healthy lifestyle activities (e.g., exercise) as compared to other forms of psychotherapy. It also is noteworthy that current depression was the most frequent reason for exclusion. There is emerging evidence among general populations that MBCT may offer benefit for individuals with current depressive symptoms (Chiesa, Mandelli, & Serretti, 2012; Dimidjian et al., 2014; Kingston, Dooley, Bates, Lawlor, & Malone, 2007; Manicavasgar, Parker, & Perich, 2011). It may be of interest for future studies to explore whether MBCT-PD has benefit specifically for women with elevated residual depressive symptoms. At the same time, it should be noted that nearly 15% of women assigned to MBCT declined participation at the time of randomization, with concerns about time commitment as the most common reason provided. Delivery methods that minimize time burden and inconvenience for pregnant women will be important to examine; options may include phone-based delivery of MBCT (Thompson et al., 2010) and web-based delivery (Dimidjian et al., 2014).

Several limitations should be considered. First, the potential impact of differential retention of patients in the study must be acknowledged. Although overall rates of participants lost to follow up were comparable across study conditions during the intervention and follow-up phases of the study, the rates of refusal at the time of allocation were higher among participants assigned to MBCT-PD. Second, our sample was predominantly White, college educated, and employed; it is important for future research to examine the extent to which these findings can be generalized to ethnically and racially diverse populations and to women who are financially disadvantaged. Third, despite strong interest in the impact of preventive interventions on fetal and infant development, we were unable to study such outcomes in this trial and believe that this area is a high priority for future research. That we examined outcomes only through six months postpartum also prohibited us from testing the extent to which any benefits of MBCT were enduring and extended to future pregnancies. These are important questions for future studies to examine. Finally, this study does not address the mechanisms of change in MBCT. MBCT is based on a clear theory and supporting data regarding how depression can be prevented by the cultivation of mindfulness skills (Teasdale et al., 2002); however, the extent to which such mechanisms explain the prophylactic effect of MBCT among at risk pregnant women awaits future study. It would be of value for future studies to examine the extent to which home practice predicts protection from relapse and to examine specific putative mechanisms, such as rumination and decentering. A growing body of research suggests that rumination may play a role in perinatal depression (Barnum, Woody, & Gibb, 2013; O’Mahen, Flynn, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2010). Studies in the general population have found that rumination decreased during MBCT for formerly depressed individuals (Michalak, Holz, & Teismann, 2011; Shahar, Britton, Sbarra, Figueredo, & Bootzin, 2010) and that post-treatment rumination predicted depressive relapse (Michalak et al., 2011). A small body of research has shown that higher decentering is associated with lower rates of relapse among individuals in partial remission (Teasdale et al., 2002), and that MBCT increases decentering (Bieling et al., 2012; Teasdale et al., 2002). The role of self-compassion also should be a focus of future work on MBCT-PD given indications that self-compassion is a key process in MBCT (Kuyken et al., 2010) and that self-critical attitudes about motherhood are associated with perinatal depression and anxiety (Sockol, Epperson, & Barber, 2014). Finally, it may be important to examine potential domains of vulnerability that are of relevance during the perinatal period, such as the role of social support, which have not been widely studied in prior work on MBCT.

In summary, our findings suggest that MBCT-PD, teaching skills and practices to stay well during pregnancy and the early postpartum, may have preventive benefits for pregnant women with histories of depression. Women who received MBCT-PD experienced an approximately 30% reduction in risk of depressive relapse/recurrence compared to TAU. Given that prior history of depression is one of the most robust risk factors for depression, it is possible to identify a subgroup of pregnant women who are at elevated risk for the return of depression during this important life transition. Moreover, our knowledge of the correlates and consequences of perinatal depression and the critical nature of this period for fetal and infant development provides a compelling rationale to promote policy and practice that supports the well-being of women and children. Although this study warrants replication in studies that address the limitation noted, our findings may have important public health implications for women and their care providers considering options for depression care management during pregnancy and the postpartum.

Acknowledgments

Dimidjian and Goodman receive royalties from Guilford Press for work related to Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy and Dimidjian is on the advisory board of MindfulNoggin, which is part of NogginLabs, a private company specializing in customized web based learning.

Contributor Information

Sona Dimidjian, University of Colorado Boulder

Sherryl H. Goodman, Emory University

Jennifer Felder, University of Colorado Boulder.

Robert Gallop, West Chester University

Amanda P. Brown, Emory University.

Arne Beck, Kaiser Permanente – Institute for Health Research

References

- APA. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Attkisson CC, Zwick R. The client satisfaction questionnaire: Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1982;5(3):233–237. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(82)90074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnum SE, Woody ML, Gibb BE. Predicting Changes in Depressive Symptoms from Pregnancy to Postpartum: The Role of Brooding Rumination and Negative Inferential Styles. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2013;37(1):71–77. doi: 10.1007/s10608-012-9456-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck CT. Predictors of postpartum depression - An update. Nurs Res. 2001;50(5):275–285. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieling PJ, Hawley LL, Bloch RT, Corcoran KM, Levitan RD, Young LT, Segal ZV. Treatment-specific changes in decentering following mindfulness-based cognitive therapy versus antidepressant medication or placebo for prevention of depressive relapse. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(3):365–372. doi: 10.1037/a0027483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Box GEP, Cox DR. An analysis of Transformations. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society B. 1964;26:211–243. [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa A, Mandelli L, Serretti A. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy versus psycho-education for patients with major depression who did not achieve remission following antidepressant treatment: A preliminary analysis. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2012;18(8):756–760. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa A, Serretti A. Mindfulness based cognitive therapy for psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2011;187(3):441–453. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LS, Altshuler LL, Harlow BL, Nonacs R, Newport DJ, Viguera AC, Stowe ZN. Relapse of major depression during pregnancy in women who maintain or discontinue antidepressant treatment. JAMA. 2006;295(5):499–507. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.5.499. doi: 295/5/499 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz PM, Williams SB, Callaghan WM, Bachman DJ, Whitlock EP, Hornbrook MC. Clinically identified maternal depression before, during, and after pregnancies ending in live births. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(10):1515–1520. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Florio A, Forty L, Gordon-Smith K, Heron J, Jones L, Craddock N, Jones I. Perinatal episodes across the mood disorder spectrum. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(2):168–175. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimidjian S, Beck A, Felder JN, Boggs JM, Gallop R, Segal ZV. Web-based Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy for reducing residual depressive symptoms: An open trial and quasi-experimental comparison to propensity score matched controls. Behav Res Ther. 2014;63:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimidjian S, Goodman SH. Preferences and attitudes toward approaches to depression relapse/recurrence prevention among pregnant women. Behaviour research and therapy. 2014;54:7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimidjian S, Goodman SH, Felder JN, Gallop R, Brown AP, Beck A. An open trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for the prevention of perinatal depressive relapse/recurrence. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2015;18:85–94. doi: 10.1007/s00737-014-0468-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan LG, Bardacke N. Mindfulness-Based Childbirth and Parenting Education: Promoting Family Mindfulness During the Perinatal Period. J Child Fam Stud. 2010;19(2):190–202. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9313-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn C, Hanieh E, Roberts R, Powrie R. Mindful pregnancy and childbirth: effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on women’s psychological distress and well-being in the perinatal period. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15(2):139–143. doi: 10.1007/s00737-012-0264-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1999;94(446):496–509. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Miriam G, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Lorna B. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. (SCID-I/P) New York: Biometrics Research; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression - A systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(5):1071–1083. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman JH, Guarino A, Chenausky K, Klein L, Prager J, Petersen R, Freeman M. CALM Pregnancy: results of a pilot study of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for perinatal anxiety. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00737-013-0402-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Dimidjian S, Williams KG. Pregnant African American women’s attitudes toward perinatal depression prevention. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2013;19(1):50–57. doi: 10.1037/a0030565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth MR, Hall CM, Heyward D. Maternal Depression and Child Psychopathology: A Meta-Analytic Review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2011;14(1):1–27. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Tully EC. Recurrence of depression during pregnancy: Psychosocial and personal functioning correlates. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(6):557–567. doi: 10.1002/da.20421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Stat Med. 1999;18(6):695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MB, Lavori PW, Friedman B, Nielsen E, Endicott J, McDonaldscott P, Andreasen NC. The longitudinal interval follow-up evaluation: A comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;44(6):540–548. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston T, Dooley B, Bates A, Lawlor E, Malone K. Mindfulness- based cognitive therapy for residual depressive symptoms. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 2007;80(2):193–203. doi: 10.1348/147608306X116016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuyken W, Watkins E, Holden E, White K, Taylor RS, Byford S, Dalgleish T. How does mindfulness-based cognitive therapy work? Behav Res Ther. 2010;48(11):1105–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le HN, Perry DF, Stuart EA. Randomized controlled trial of a preventive intervention for perinatal depression in high-risk Latinas. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79(2):135–141. doi: 10.1037/a0022492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma SH, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: Replication and exploration of differential relapse prevention effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(1):31–40. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.72.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manicavasgar V, Parker G, Perich T. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy vs cognitive behaviour therapy as a treatment for non-melancholic depression. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(1–2):138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalak J, Holz A, Teismann T. Rumination as a predictor of relapse in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 2011;84(2):230–236. doi: 10.1348/147608310x520166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L, Carothers AD. The validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale on a community sample. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;157:288–290. doi: 10.1192/bjp.157.2.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression - A meta-analysis. International Review of Psychiatry. 1996;8(1):37–54. [Google Scholar]

- O’Mahen HA, Flynn HA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination and Interpersonal Functioning in Perinatal Depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2010;29(6):646–667. [Google Scholar]

- Patel SR, Wisner KL. Decision making for depression treatment during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(7):589–595. doi: 10.1002/da.20844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson RM, Evans J, Kounali D, Lewis G, Heron J, Ramchandani PG, Stein A. Maternal Depression During Pregnancy and the Postnatal Period: Risks and Possible Mechanisms for Offspring Depression at Age 18 Years. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piet J, Hougaard E. The effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for prevention of relapse in recurrent major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(6):1032–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roca A, Imaz ML, Torres A, Plaza A, Subira S, Valdes M, Garcia-Esteve L. Unplanned pregnancy and discontinuation of SSRIs in pregnant women with previously treated affective disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(3):807–813. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, Kennedy S, Gemar M, Hood K, Pedersen R, Buis T. Cognitive reactivity to sad mood provocation and the prediction of depressive relapse. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63(7):749–755. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, Teasdale JD, Williams JMG, Gemar MC. The mindfulness-based cognitive therapy adherence scale: Inter-rater reliability, adherence to protocol and treatment distinctiveness. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2002;9(2):131–138. doi: 10.1002/cpp.320. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy for Depression: A New Approach to Preventing Relapse. Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shahar B, Britton WB, Sbarra DA, Figueredo AJ, Bootzin RR. Mechanisms of change in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: Preliminary evidence from a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2010;3(4):402–418. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2010.3.4.402. [Google Scholar]

- Sockol LE, Epperson CN, Barber JP. The relationship between maternal attitudes and symptoms of depression and anxiety among pregnant and postpartum first-time mothers. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014;17(3):199–212. doi: 10.1007/s00737-014-0424-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein A, Pearson RM, Goodman SH, Rapa E, Rahman A, McCallum M, Pariante CM. Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet. 2014;384(9956):1800–1819. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szychowski JM, Roth DL, Clay OJ, Mittelman MS. Patient death as a censoring event or competing risk event in models of nursing home placement. Stat Med. 2010;29(3):371–381. doi: 10.1002/sim.3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon SD, Perry DF, Mendelson T, Kemp K, Leis JA. Preventing perinatal depression in low-income home visiting clients: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79(5):707–712. doi: 10.1037/a0024895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale JD, Moore RG, Hayhurst H, Pope M, Williams S, Segal ZV. Metacognitive awareness and prevention of relapse in depression: Empirical evidence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(2):275–287. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale JD, Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Ridgeway VA, Soulsby JM, Lau MA. Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(4):615–623. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.4.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson NJ, Walker ER, Obolensky N, Winning A, Barmon C, Diiorio C, Compton MT. Distance delivery of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: project UPLIFT. Epilepsy Behav. 2010;19(3):247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Velden AM, Kuyken W, Wattar U, Crane C, Pallesen KJ, Dahlgaard J, Piet J. A systematic review of mechanisms of change in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in the treatment of recurrent major depressive disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;37:26–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieten C, Astin J. Effects of a mindfulness-based intervention during pregnancy on prenatal stress and mood: results of a pilot study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2008;11(1):67–74. doi: 10.1007/s00737-008-0214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JMG, Teasdale JD, Segal ZV, Soulsby J. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy reduces overgeneral autobiographical memory in formerly depressed patients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109(1):150–155. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.1.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisner KL, Perel JM, Peindl KS, Hanusa BH, Findling RL, Rapport D. Prevention of recurrent postpartum depression: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2001;62(2):82–86. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n0202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisner KL, Perel JM, Peindl KS, Hanusa BH, Piontek CM, Findling RL. Prevention of postpartum depression: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(7):1290–1292. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisner KL, Zarin DA, Holmboe ES, Appelbaum PS, Gelenberg AJ, Leonard HL, Frank E. Risk-benefit decision making for treatment of depression during pregnancy. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(12):1933–1940. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.12.1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolhouse H, Mercuri K, Judd F, Brown SJ. Antenatal mindfulness intervention to reduce depression, anxiety and stress: a pilot randomised controlled trial of the MindBabyBody program in an Australian tertiary maternity hospital. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):369. doi: 10.1186/s12884-014-0369-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonkers KA, Blackwell KA, Glover J, Forray A. Antidepressant use in pregnant and postpartum women. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:369–392. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonkers KA, Lockwood CJ, Wisner K. The Management of Depression During Pregnancy: A Report From the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Reply. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010;115(1):189–189. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c8b21d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Johnson SL, Miller IW, Pearlstein T, Howard M. Postpartum depression in women receiving public assistance: Pilot study of an interpersonal-therapy-oriented group intervention. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(4):638–640. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick C, Miller IW, Pearlstein T, Howard M, Sweeney P. A preventive intervention for pregnant women on public assistance at risk for postpartum depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(8):1443–1445. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.8.1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]