Abstract

Given the many options available, selecting an HIV test for a particular clinical or research setting can be daunting. Making an informed decision requires an assessment of the likelihood of acute infection in the test population and an understanding of key aspects of the tests themselves. The ability of individual tests to reliably detect HIV infection depends on the target(s) being detected, when they can be expected to be present following infection, and the concentration of stable target in test specimens – all of which are explained by the virological and serological events following infection. The purpose of this paper is to: review the timeline of HIV infection, nomenclature and characteristics of different tests; compare point-of-care and laboratory-based tests; discuss the impact of different specimens on test performance; and provide practical advice to help clinicians and researchers new to the field select a test that best suits their needs.

Keywords: human immunodeficiency virus, diagnostic testing, point-of-care testing, rapid testing

Introduction

Accurate knowledge of one’s HIV status remains the most important element in strategies to prevent HIV infection. Diagnosed persons can be linked to life-sustaining antiretroviral therapy that also reduces their likelihood of transmitting HIV to others, while at-risk persons can leverage a variety of behavioral and biomedical tools, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), to remain uninfected.

In the United States (US), recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) surveillance data suggest a stabilization or decrease in HIV incidence1 in the face of apparent increases in the numbers of persons tested among key risk groups.2 The reasons for these improving trends are not yet clear, but in order to be sustained, we must continue to refine systems for HIV testing and linking persons to care and prevention resources, as appropriate.

Decisions about which HIV test to use are often made behind the scenes by laboratory professionals, leaving many clinicians and researchers unfamiliar with important tests they routinely use. The purpose of this paper is to provide an overview of current HIV diagnostic technologies and recent changes in testing nomenclature, to describe how test performance varies with stage of infection and type of specimen tested, and to help individuals better understand the advantages and disadvantages of different tests, depending on their particular practice or research setting.

What is the timeline from infection to detection?

Time to reactivity for any given assay depends on: (1) the target being detected, (2) when the target is present following infection, (3) the concentration of target in the specimen, (4) the volume of specimen tested, and (5) the test’s lower limit of target detection. Because the virological and serological events following HIV infection determine when various targets become detectable,3,4 understanding this timeline is essential for understanding the limitations of different tests across clinical and research settings.

Following an exposure that leads to infection, there is a variable amount of time called the eclipse period in which no existing diagnostic test is capable of detecting HIV (Figure 1). HIV RNA is the first reliable marker of infection; 50% of infected individuals have detectable plasma RNA within 12 days4 and levels peak between 20–30 days.5 Beginning around day 15, the HIV-1 capsid protein p24 reaches detectable levels in the plasma.5 Antigenemia with p24 continues to rise through days 25–30, at which point early anti-HIV antibodies are able to complex with circulating p24; by day 50, antigen is often cleared from the bloodstream entirely.6 This short-lived detectability of p24 is therefore helpful in determining recency of infection, but also makes its utility in diagnosis time-limited.

Figure 1. Timeline of virological and serological events following HIV infection.

The length of time between an exposure event (X) and dissemination of HIV systemically depends on the mode of transmission. The eclipse period reflects time from exposure to the first detectable marker of infection: HIV RNA in the blood. Times to reactivity for each type of diagnostic test are depicted below the graph, from the earliest (nucleic acid amplification test, NAAT) to the latest (IgG sensitive assay). Adapted from Busch & Satten5 and Fiebig EW, et al. AIDS 2003;17(13):1871–9. Earliest time to reactivity estimates from Delaney, et al.4 IgM and IgG curves informed by Cooper DA, et al. J Inf Dis 1987;155(6):1113–8 and Gaines H, et al., AIDS 1988;2(1):11–5.

As with other infections, the serum antibody response starts with immunoglobulin class M (IgM) molecules, beginning to rise around day 20, peaking within another 10–15 days, and then shifting to a more mature immunoglobulin class G (IgG) response beginning between days 30–35.7

The time from infection to the first reactive result on a given test is referred to as the window period, the length of which depends on the target being detected by a particular assay. For example, tests capable of identifying anti-HIV IgM have a shorter window period than those detecting only IgG. Variability in the time needed for targets to rise to detectable levels in different persons means the window period actually reflects a distribution of time rather than a fixed length that is identical for everyone (Table 1).

Table 1.

Window periods of HIV tests, by category.

| Category (Number of Tests Included) | 25%* will have a reactive result by day | 50%* will have a reactive result by day | 75%* will have a reactive result by day | 99%* will have a reactive result by day |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p24/IgM/IgG sensitive laboratory tests (4)† | 13.0 | 17.8 | 23.6 | 44.3 |

| p24/IgM/IgG sensitive POC test (1)‡ | 14.8 | 19.2 | 24.6 | 43.1 |

| IgM/IgG sensitive laboratory tests (3)§ | 18.4 | 23.1 | 28.8 | 49.5 |

| IgM/IgG sensitive POC tests (2)‖ | 24.2 | 29.3 | 35.3 | 57.4 |

| IgG sensitive laboratory test (1)¶ | 26.5 | 30.6 | 35.9 | 54.1 |

| IgG sensitive POC tests (5)** | 26.7 | 31.8 | 37.8 | 57.8 |

| IgG sensitive supplemental tests (1)†† | 28.2 | 32.9 | 38.6 | 57.7 |

| Western blot (1)‡‡ | 31.0 | 36.5 | 43.2 | 64.8 |

Columns correspond to the 25th, 50th, 75th, and 99th percentiles of window period distributions, averaged across all tests in a given category, as calculated by Delaney, et al.6

ADVIA Centaur HIV Ag/Ab Combo, ARCHITECT HIV Ag/Ab Combo, BioPlex 2200 HIV Ag-Ab, and GS HIV Combo Ag/Ab EIA

Determine HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab Combo

ADVIA Centaur HIV 1/O/2 Enhanced, GS HIV-1/2 PLUS O EIA, and VITROS Anti-HIV 1+2

INSTI HIV-1/HIV-2 Rapid and Uni-Gold Recombigen HIV

Avioq HIV-1 Microelisa System

Clearview HIV 1/2 STAT-PAK, DPP HIV-1/2, OraQuick ADVANCE Rapid HIV-1/2, Reveal G2 Rapid HIV-1 Antibody, and SURE CHECK HIV 1/2

Geenius HIV-1/2 Ab Supplemental

Unbranded viral lysate

What serological tests are available for HIV?

Since the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first HIV diagnostic test in 1985, four additional “generations” of antibody tests for HIV have been developed; each improves incrementally on its predecessor(s) in terms of performance and shortening of the window period3,8 (Figure 2). The official nomenclature for HIV testing is currently changing, with categorizations based on analytic target(s) instead of generation numbers.9 For example, first- and second-generation assays are now referred to as “IgG sensitive,” since they are capable of detecting only IgG. Each category of tests may be further subcategorized as point-of-care (POC) or laboratory-based (Table 2).

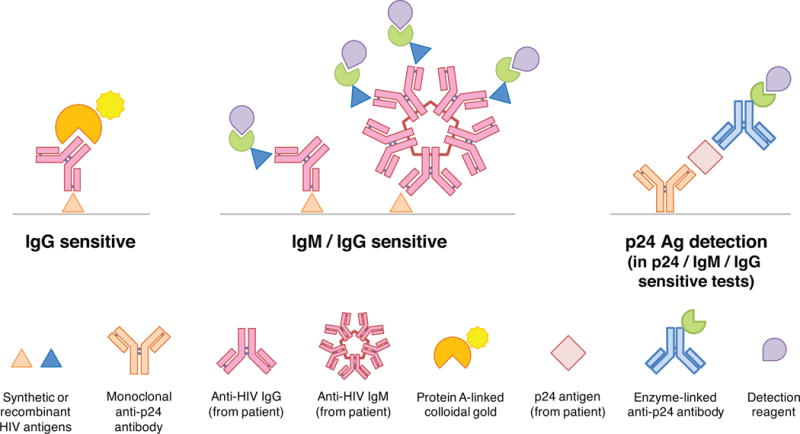

Figure 2. HIV serological tests.

In IgG sensitive tests, anti-HIV IgG from a patient’s specimen binds to immobilized HIV antigens on the solid phase of the assay (gray line); detection most often uses protein A conjugated to colloidal gold. IgM/IgG sensitive tests permit binding of both IgM and IgG from specimens, with detection accomplished using labeled, synthetic HIV antigens (enzymatically-linked or conjugated to a chemiluminescent marker). The addition of simultaneous, monoclonal antibody-mediated p24 antigen detection distinguishes Ag/Ab combination assays from IgM/IgG sensitive tests.

Table 2.

FDA-approved tests for HIV in 2017

| Performance in Established HIV-1 Infection§ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test (Manufacturer) | Type* | Specimens† | Minutes to result | CLIA complexity (waivers)‡ | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) |

| p24/IgM/IgG sensitive laboratory test | ||||||

| ADVIA Centaur HIV Ag/Ab Combo (Siemens) | Auto CMIA | P, S | <60 | Moderate | 100 (99.61, 100) | 99.72 (99.56, 99.84) |

| ARCHITECT HIV Ag/Ab Combo (Abbott) | Auto CMIA | P, S | <30 | Moderate | 100 (99.63, 100) | 99.8 (99.6, 99.9) |

| BioPlex 2200 HIV Ag-Ab (Bio-Rad) | Auto MFIA | P, S | 45 | Moderate | 100 (9.72, 100) | 99.92 (99.82, 99.97) |

| GS HIV Combo Ag/Ab EIA (Bio-Rad) | Manual/semi-auto EIA | P, S | >180 | High | 100 (99.7, 100) | 99.9 (99.8, 99.9) |

| p24/IgM/IgG sensitive POC test | ||||||

| Determine HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab Combo (Alere) | Rapid LF | P, S, WB | 20 | Moderate (WB) | 99.9 (99.4, 100) | 98.9–100 (97.7, 100) |

| IgM/IgG sensitive laboratory test | ||||||

| ADVIA Centaur HIV 1/O/2 Enhanced (Siemens) | Auto CMIA | P, S | <60 | Moderate | 100 (99.7, 100) | 99.9 (99.8, 100) |

| GS HIV-1/2 PLUS O EIA (Bio-Rad) | Manual/semi-auto EIA | P, S | >180 | High | 100 (99.8, 100) | 99.9 (99.8, 100) |

| VITROS Anti-HIV 1+2 (Ortho) | Auto CIA | P, S | <60 | High | 100 (99.7, 100) | 99.6 (99.1, 99.9) |

| IgM/IgG sensitive POC test | ||||||

| INSTI HIV-1/HIV-2 Rapid (BioLytical) | Rapid FT | P, WB | <2 | Moderate (WB) | 99.9 (99.5, 100) | 100 (99.7, 100) |

| Uni-Gold Recombigen HIV (Trinity BioTech) | Rapid LF | P, S, WB | 10 | Moderate (WB) | 100 (99.5, 100) | 99.8 (99.3, 100) |

| IgG sensitive laboratory test | ||||||

| Avioq HIV-1 Microelisa System (Avioq) | Auto EIA | P, S, DBS, OF | >180 | High | 100 (99.6, 100) | 100 (99.9, 100) |

| IgG sensitive POC test | ||||||

| Clearview HIV 1/2 STAT-PAK (Alere) | Rapid LF | P, S, WB | 15 | Moderate (WB) | 99.7 (98.9, 100) | 99.9 (99.6, 100) |

| DPP HIV-1/2 (Chembio) | Rapid LF | P, S, WB, OF | 15 | Moderate (WB) | 99.9 (99.4, 99.9) | 99.9 (99.7, 99.9) |

| OraQuick ADVANCE Rapid HIV-1/2 (OraSure) | Rapid LF | P, WB, OF | 20 | Moderate (WB & OF) | 99.6 (98.9, 99.8) | 99.9 (99.6, 99.9) |

| Reveal G3 Rapid HIV-1 Antibody (MedMira) | Rapid FT | P, S | <2 | Moderate | 99.8 (99.0, 100) | 98.6–99.1 (98.4, 99.8) |

| SURE CHECK HIV 1/2 ‖ (Chembio) | Rapid LF | P, S, WB | 15 | Moderate (WB) | 99.7 (98.9, 100) | 99.9 (99.6, 100) |

| Supplemental test | ||||||

| Geenius HIV-1/2 Ab Supplemental (Bio-Rad) | Rapid LF | P, S, WB | 20 | High | 99.3 (97.6, 99.8) | 4.3% indeterminate |

| Aptima HIV-1 RNA Qualitative (Hologic) | NAT (TMA) | P, S | >180 | High | 100 (99.6, 100) | – |

Data from CDC, accessed 26 February 2017: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/testing/hiv-tests-laboratory-use.pdf and https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/testing/rapid-hiv-tests-clinical-moderate-complexity.pdf and https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/testing/supplemental-hiv-tests-laboratory-use.pdf. Abbreviations: Auto, automated; CIA, chemiluminescent immunoassay; CMIA, chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay; CLIA, Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments; EIA, enzyme immunoassay; FT, flow-through; LF, lateral flow; MFIA, multiplex flow immunoassay; NAT, nucleic acid test; RNA, ribonucleic acid; TMA, transcription-mediated amplification

Abbreviations: DBS, dried blood spot; OF, oral fluid; P, plasma; S, serum; WB, whole blood

Requirements for laboratory training are waived for the specimen type(s) listed in parentheses (i.e., unprocessed samples direct from patients). Data from Branson.5

Sensitivity and specificity in the table reflect performance of the individual assay in established (i.e., seropositive) HIV infection.

Before 2016, this test was marketed as Clearview COMPLETE HIV 1/2 (Alere)

In IgG sensitive tests, anti-HIV antibodies from patient specimens bind to recombinant or synthetic HIV antigens immobilized on the solid phase of the assay (typically gp41 for HIV-1 and gp36 for HIV-2), after which a detection reagent is applied. For POC tests, the detection reagent is often a conjugate of protein A (an immunoglobulin-avid, recombinant bacterial peptide) with colloidal gold or selenium.3 The increased purity of synthetic antigens contributed to a shortening of the median window period from 45 days for viral lysate assays (such as the Western blot)10 to 31 days with current IgG sensitive POC tests.4 The antibody-based supplemental test (which has replaced the Western blot in the US testing algorithm8), is a specialized, rapid, IgG sensitive laboratory assay featuring multiple recombinant antigens from both HIV-1 and HIV-2. This allows confirmation of the presence of anti-HIV IgG and differentiation of HIV-1 from HIV-2 – all within 30 minutes.

IgM/IgG sensitive (formerly third generation) tests shorten the window period to the earliest threshold of IgM detection – a median of 23 days after infection.4 As with IgG sensitive assays, solid-phase antigens bind antibody from the patient specimen, but instead of labeled protein A applied for detection purposes, a second, labeled or enzyme-linked synthetic HIV antigen is used, in a method referred to as an “antigen sandwich.”

Antigen/antibody (Ag/Ab) combination (formerly fourth generation) tests pair an IgM/IgG sensitive antibody test with simultaneous, separate p24 antigen detection. Antigen from the patient specimen is first captured by immobilized, anti-p24 antibody on the solid phase of the assay, and then a separate, labeled anti-p24 antibody is applied, forming an “antibody sandwich.” Some of these p24/IgM/IgG sensitive tests report a reactive result if any element is detected, while others yield separate results for p24, anti-HIV-1 antibodies, and anti-HIV-2 antibodies. Detecting p24 shortens the median window period down to just 18 days following infection.4

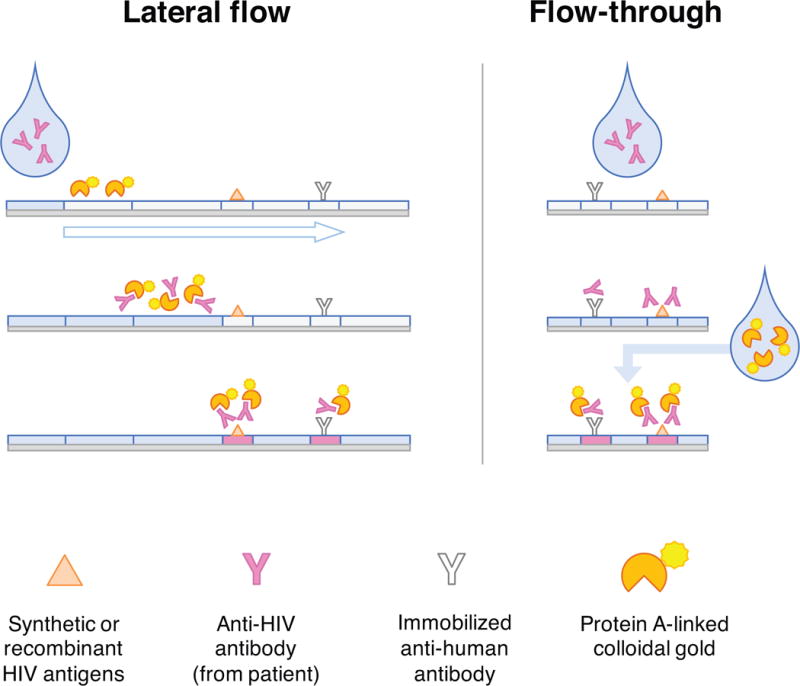

In contrast to complex, automated laboratory-based platforms, POC tests rely on one of two methods: lateral flow, in which the specimen is drawn through an antigen-impregnated strip by capillary action; or flow-through, in which the patient’s specimen and reagents are sequentially applied to a membrane embedded with HIV antigens (Figure 3). Detection is accomplished most often with protein A-colloidal gold conjugates, either rehydrated from within the lateral flow strip or added separately to flow-through assays.

Figure 3. HIV rapid tests.

In lateral flow assays, specimen from a patient is added to one end of a nitrocellulose strip. As capillary action draws the specimen toward a wicking pad at the opposite end (open arrow), detection reagents are rehydrated and bind to patient antibodies. Anti-HIV antibodies present in the specimen bind immobilized HIV antigens in the test line, while anti-human antibodies on the control line non-specifically bind any immunoglobulin from the specimen. Accumulated colloidal gold produces a visible color change. “Dual path” tests combine two perpendicular lateral flow strips in a single test cassette. Patient specimen and buffer solution migrate through the first strip, depositing antibodies where the strips intersect and washing away colored markers that identify the second strip’s control and test lines. Once the markers have disappeared, additional reagents are applied to the second strip, rehydrating detection reagents to react with the patient specimen. Flow-through tests use a similar approach, except the detection reagent (e.g., protein A) is added separately rather than rehydrated from the test membrane. Generally, flow-through tests yield a result faster than lateral flow tests can.

What influence does specimen type have on testing?

Laboratory-based serum or plasma assays generally offer higher sensitivities, but require venipuncture, larger specimen volumes, processing, and skilled technicians. POC tests are attractive alternatives for many applications, but performance differs substantially depending on the specimen type; tests using oral transudate are significantly less sensitive than those using whole blood, and tests using whole blood are less sensitive than those using serum or plasma.11–14 This hierarchy is at least partially explained by the relative concentration of detectable target(s) per volume of specimen tested. Forty-five percent of whole blood is made up of cells, so additional processing to yield plasma or serum further concentrates antigens and antibodies per unit volume.

Compared with plasma, oral transudate immunoglobulin concentrations are 300-fold lower.15 Because oral antibodies rise to detectable levels later than those in blood, the window period is prolonged when oral fluid is used for testing. This was demonstrated most clearly in a study of HIV seroconverters in Nigeria, in which antibodies in oral transudate became detectable a median of 29 days after those in plasma.16

What advantages do POC tests have over laboratory-based assays?

The introduction of the first FDA-approved rapid test in 2002 and changes in regulations permitting use of certain tests outside of laboratory settings revolutionized the process of getting tested for HIV.3 POC tests are portable and easy to use, and the ability to perform HIV testing on oral transudate or fingerstick whole blood eliminates the need for venipuncture and the handling, processing, or storage of blood. This can make the entire encounter self-contained, allowing for anonymous testing where permitted by law. POC tests also greaty increase the likelihood that the patient receives her/his result. These tests have one key disadvantage, however: although the eight current FDA-approved POC tests have excellent and generally comparable performance characteristics (Table 2), laboratory-based tests have greater sensitivity – especially early after infection.

Indeed, acute HIV-1 infection (AHI) remains a critical blind spot for current POC tests. Because AHI is characterized by the presence of p24 or HIV-1 RNA in the absence of detectable anti-HIV-1 antibodies, antibody-only tests cannot diagnose AHI. Multiple laboratory-based p24/IgM/IgG platforms are available (Table 2), but development of a POC version with comparable performance has proven more challenging. The first such test was approved by the FDA in 2013 (Determine HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab Combo, Alere, Stockport, UK). Field evaluations have demonstrated excellent sensitivity for antibody detection but variable, suboptimal sensitivity for p24.17 Studies of a newer version of this same test suggest interim improvements, with antigen sensitivity as high as 88%.14,18 Using plasma instead of whole blood enhances test performance, suggesting a role for this test in situations when laboratory support is available but an automated platform is not.14

How should PrEP use influence HIV test selection?

Data are accumulating that users of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF)-based PrEP who become infected in the context of poor adherence may have delayed seroconversion on blood-based and oral POC tests. In the Partners PrEP Study, participants underwent POC testing on whole blood with both IgM/IgG and p24/IgM/IgG sensitive tests and had samples sent for multiple laboratory-based assays every 3 months.19 Delayed seroconversion was defined as >100 days between the first laboratory-based evidence of infection and the first POC test reactivity for the participant. Compared with those on placebo, participants with any pharmacological evidence of adherence during the seroconversion period had 7.2 times the odds of delayed seroconversion; plasma RNA levels were lower, as well – but still detectable.19 Among participants randomized to receive single-agent TDF in the Bangkok Tenofovir Study who subsequently became HIV-infected, oral antibody reactivity trailed the first evidence of HIV (antibody or RNA) in blood by a median of 126.5 days.20 Taken together, these findings underscore the importance of using laboratory-based serum or plasma tests whenever possible in the management of PrEP users and having a low threshold for augmenting p24/IgM/IgG sensitive assays with nucleic acid testing among users with known or suspected poor adherence.

What algorithm is recommended for HIV testing?

All HIV diagnostic testing is guided by a common principle: screen with a highly sensitive initial test and confirm reactive results with a different test that is both sensitive and highly specific. This can be accomplished using two POC tests, two laboratory-based assays, or combinations thereof; all of these strategies have been studied extensively.

In areas of the world without routine access to laboratory services,21 POC test-based strategies are the standard for diagnosis, and two approaches have been examined.22 Serial testing more closely approximates a “traditional” screening and confirmation approach by combining two different POC tests in sequence; if an initial result is reactive, a second test is run. Because discordant results may indicate recent infection, guidelines recommend either retesting in several weeks or referral for laboratory-based testing.21 In parallel testing, two different POC tests are run simultaneously, with a separate, third test used as a tiebreaker for discrepancies. In 2004, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended serial testing for resource-limited settings, provided that the sensitivity and specificity of tests selected are ≥99%.21

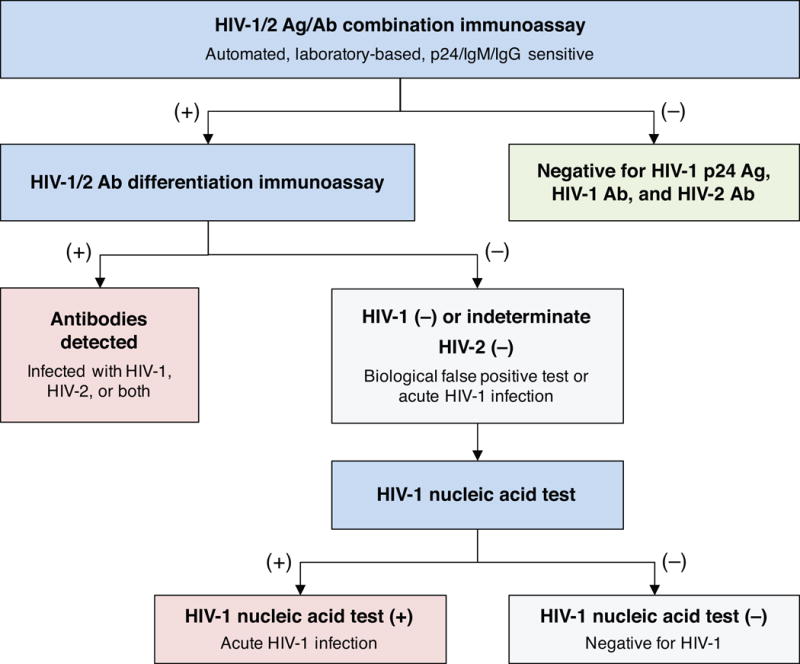

Although two-step testing with POC assays is an acceptable, evidence-based option for HIV diagnosis in the US,23 the majority of testing ordered in clinical encounters is processed according to the 2014 algorithm for laboratory-based HIV diagnosis (Figure 4).8 Any reactive initial Ag/Ab combination test is confirmed using an IgG sensitive HIV-1/2 antibody differentiation supplemental assay – a highly specific, faster, and less labor-intensive replacement for the Western blot.24 Indeterminate or negative supplemental assay results must be confirmed with nucleic acid testing (NAT); the presence of HIV-1 RNA distinguishes a false-positive screening test from a likely case of AHI. Although in practice, any qualitative or quantitative HIV-1 RNA assay could be used for diagnosis (contingent on local policies and laboratory validations), only one is currently FDA-approved for that purpose.3

Figure 4. Recommended laboratory HIV testing algorithm.

Any assay capable of reliably detecting p24 antigen (Ag) and both IgM and IgG antibodies (Ab) is the recommended starting point for HIV screening in the CDC algorithm, updated in 2014. Reactive specimens from the initial test are subjected to an IgG-sensitive supplemental immunoassay capable of differentiating HIV-1 from HIV-2; this step replaces the HIV-1 Western blot. Indeterminate or negative results from the differentiation test indicate either acute HIV infection (positive for p24 antigen or IgM antibody) or a biological false positive test; the presence of detectable HIV RNA on a subsequent nucleic acid test is the arbitrator. Adapted from CDC.8

Summary and recommendations for specific situations

Selecting an HIV test for a given situation requires balancing client characteristics and programmatic concerns against test performance (i.e., its sensitivity and specificity with different specimen types, its reliability in detecting AHI, and its ability to identify HIV-2 infections).25 At the client level, variation in individual preferences and testing patterns comes into play. Some individuals may be less willing to provide blood samples or to return at a later date for a test result, both of which have implications for selecting a POC test over a laboratory-based platform. Program-level considerations include building or maintaining laboratory capacity, training and supervising personnel, assuring quality, following up with clients, complying with local public health reporting requirements, and budgeting. With this framework and the data presented in mind, let us consider four specific situations: testing after an exposure event, screening populations at high risk of infection, outreach testing in developed countries, and selection of HIV tests for global health research.

Testing after an exposure event

HIV testing is often prompted by a defined exposure, such as a needlestick injury, condom failure, or condomless sex. Because no diagnostic test is capable of detecting infection in the eclipse period, baseline testing is obtained to rule out undiagnosed, pre-existing infection in the patient. Blood-based POC testing should be used whenever possible, in order to facilitate prompt initiation of post-exposure prophylaxis (if indicated).26,27 Strong preference should be given to an Ag/Ab combination test over antibody-only options, and oral fluid should not be used. Follow-up testing should occur 4–6 weeks and 3 months after baseline, with additional testing at 6 months if the exposure event resulted in hepatitis C virus infection.27 If the patient tests negative at the end of the window period (Table 1), one can be very confident that s/he did not acquire HIV from the exposure.

Screening high-incidence populations

POC and laboratory-based tests perform similarly well for the detection of established, chronic HIV infections, provided that blood-based specimens are used. (Although rare, false-negative oral POC tests have been reported in patients with advanced HIV disease.28,29) In populations with a greater likelihood of recent infection (including persons on tenofovir-based PrEP), maximizing sensitivity to detect AHI is critical. To accomplish this, laboratory-based p24/IgM/IgG sensitive assays on serum or plasma should be used whenever possible. In settings with support for specimen processing but without an automated test platform, using serum or plasma with a p24/IgM/IgG sensitive POC test will improve its sensitivity (compared to whole blood)11,13,14 and offers the potential for earlier diagnosis than with IgM/IgG sensitive tests. Although most people with symptomatic HIV-1 acute retroviral syndrome (e.g., fever, pharyngitis, and lymphadenopathy) will have detectable p24 antigenemia, adding a nucleic acid test to the diagnostic workup (where available) may help capture the small proportion of those with recent infections who are RNA-positive but antigen-negative. (This situation may occur either very soon after the eclipse period has ended or in a rare, second window period after p24 has cleared but before IgM has become detectable.30)

Outreach testing in developed countries

Mobile testing units, syringe exchange programs, and community testing events place a premium on test portability, ease of administration, flexibility in specimen type, and rapid turnaround of results – all of which make POC tests an obvious, frequent choice. However, longer window periods (Table 1) and lower sensitivities (Table 2) with POC assays compared to their laboratory-based counterparts are important trade-offs to consider. Because some outreach testing populations may be more likely to have recent HIV infection, IgM/IgG sensitive POC tests (including p24/IgM/IgG sensitive assays) should be prioritized over those capable of detecting IgG only. Whenever logistically feasible, serum or plasma should be tested instead of whole blood, and consideration should be given to sending a specimen for laboratory platform testing in addition to the POC test. Oral transudate should be used as a specimen only when obtaining blood (through venipuncture or fingerstick) is impractical or undesirable.13 Patients and testing clients considering oral HIV self-testing should be counseled about its longer window period compared to either blood-based POC tests or laboratory-based assays.

Selection of tests for global health research

Investigators new to HIV testing and prevention may wish to incorporate screening as part of study designs in resource-limited areas internationally. The first step is to familiarize oneself with local testing standards and approved options. As much as possible, serum or plasma should be used as the test specimen instead of whole blood to help maximize test sensitivity, and preference should be given to using nationally approved IgM/IgG sensitive POC tests (including Ag/Ab combination assays) over IgG sensitive tests. For most jurisdictions, reactive results from two sequential (and different) POC tests can be used for diagnosis, in accordance with WHO guidelines.21 One can be confident in making a diagnosis of HIV from concordant results in a serial POC testing algorithm if the prevalence of infection in the test population is high (≥5%), provided that highly sensitive and specific (both ≥99%) POC tests were employed. In lower-prevalence populations, the false-positive rate will always be higher with a highly sensitive test; laboratory-based confirmatory testing may help prevent unnecessary HIV care, though it is not always possible to obtain. Finally, in areas with a significant prevalence of HIV-2 or subtype O HIV-1 (primarily in western Africa), the selected tests must be capable of reliably detecting those viruses with adequate sensitivity and specificity.

Conclusions

The variety and complexity of available HIV test platforms can be daunting for clinicians or researchers trying to decide on the right test for their particular programmatic needs. By taking time to understand the timeline of virological and serological events following infection, the context of test use, how the various tests work, and the advantages and disadvantages of POC tests versus laboratory-based assays, it is possible to make better, more informed choices that improve one’s confidence in the outcome of HIV testing.

SUMMARY.

This narrative review, intended for those new to HIV testing and prevention, summarizes current testing technologies and discusses key considerations in selecting appropriate tests for different clinical and research applications.

Acknowledgments

Based on a presentation given by CBH at a joint consultation on “Enhancing the Measurement of HIV Exposure Due to Sexual Behavior” for the National Institute of Mental Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease on March 22, 2016.

Conflicts of Interest and Sources of Funding

CBH is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; K23MH099941). JAEN is supported by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (P30AI50410). LHW is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver Institute for Child Health and Human Development (NICHD; R43HD088319). WCM was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID; R01AI114320) and NICHD (R01HD080485). The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Hall HI, Song R, Tang T, et al. HIV trends in the United States: diagnoses and estimated incidence. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2017;3(1):e8. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.7051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seth P, Walker T, Figueroa A. CDC-funded HIV testing, HIV positivity, and linkage to HIV medical care in non-health care settings among young men who have sex with men (YMSM) in the United States. AIDS Care. 2016:1–5. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1271104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Branson BM. HIV testing updates and challenges: when regulatory caution and public health imperatives collide. Current HIV/AIDS reports. 2015;12(1):117–126. doi: 10.1007/s11904-014-0251-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delaney KP, Hanson DL, Masciotra S, Ethridge SF, Wesolowski L, Owen SM. Time until emergence of HIV test reactivity following infection with HIV-1: implications for interpreting test results and retesting after exposure. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(1):53–59. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Busch MP, Satten GA. Time course of viremia and antibody seroconversion following human immunodeficiency virus exposure. Am J Med. 1997;102(5B):117–124. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00077-6. discussion 125–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henrard DR, Daar E, Farzadegan H, et al. Virologic and immunologic characterization of symptomatic and asymptomatic primary HIV-1 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;9(3):305–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper DA, Imrie AA, Penny R. Antibody response to human immunodeficiency virus after primary infection. J Infect Dis. 1987;155(6):1113–1118. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.6.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Branson BM, Owen SM, Wesolowski LG, et al. Laboratory Testing for the Diagnosis of HIV Infection: Updated Recommendations. 2014 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/HIVtestingAlgorithmRecommendation-Final.pdf.

- 9.Wesolowski LG, Parker MM, Delaney KP, Owen SM. Highlights from the 2016 HIV diagnostics conference: The new landscape of HIV testing in laboratories, public health programs and clinical practice. J Clin Virol. 2017;91:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2017.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petersen LR, Satten GA, Dodd R, et al. Duration of time from onset of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectiousness to development of detectable antibody. The HIV Seroconversion Study Group. Transfusion. 1994;34(4):283–289. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1994.34494233574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pavie J, Rachline A, Loze B, et al. Sensitivity of five rapid HIV tests on oral fluid or finger-stick whole blood: a real-time comparison in a healthcare setting. PloS one. 2010;5(7):e11581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pilcher CD, Louie B, Facente S, et al. Performance of rapid point-of-care and laboratory tests for acute and established HIV infection in San Francisco. PloS one. 2013;8(12):e80629. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stekler JD, O’Neal JD, Lane A, et al. Relative accuracy of serum, whole blood, and oral fluid HIV tests among Seattle men who have sex with men. J Clin Virol. 2013;58(Suppl 1):e119–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masciotra S, Luo W, Westheimer E, et al. Performance evaluation of the FDA-approved Determine HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab Combo assay using plasma and whole blood specimens. J Clin Virol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2017.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mortimer PP, Parry JV. Detection of antibody to HIV in saliva: a brief review. Clin Diagn Virol. 1994;2:231–243. doi: 10.1016/0928-0197(94)90048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo W, Masciotra S, Delaney KP, et al. Comparison of HIV oral fluid and plasma antibody results during early infection in a longitudinal Nigerian cohort. J Clin Virol. 2013;58(Suppl 1):e113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conway DP, Holt M, McNulty A, et al. Multi-centre evaluation of the Determine HIV Combo assay when used for point of care testing in a high risk clinic-based population. PloS one. 2014;9(4):e94062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitzgerald N, Cross M, O’Shea S, Fox J. Diagnosing acute HIV infection at point of care: a retrospective analysis of the sensitivity and specificity of a fourth-generation point-of-care test for detection of HIV core protein p24. Sexually transmitted infections. 2017;93(2):100–101. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2015-052491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donnell D, Ramos E, Celum C, et al. The effect of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis on the progression of HIV-1 seroconversion. AIDS. 2017 doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curlin ME, Gvetadze R, Leelawiwat W, et al. Analysis of false-negative HIV rapid tests performed on oral fluid in three international clinical research studies. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 doi: 10.1093/cid/cix228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. Rapid HIV tests: guidelines for use in HIV testing and counseling services in resource-constrained settings. 2004 http://applications.emro.who.int/aiecf/web28.pdf.

- 22.Wright RJ, Stringer JS. Rapid testing strategies for HIV-1 serodiagnosis in high-prevalence African settings. American journal of preventive medicine. 2004;27(1):42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Implementing HIV testing in nonclinical settings: a guide for HIV testing providers. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Technical update on HIV-1/2 differentiation assays. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/40790/cdc_40790_DS1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Planning and implementing HIV testing and linkage programs in non-clinical settings: a guide for program managers. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuhar DT, Henderson DK, Struble KA, et al. Updated US Public Health Service Guidelines for the management of occupational exposures to human immunodeficiency virus and recommendations for postexposure prophylaxis. Infection control and hospital epidemiology: the official journal of the Society of Hospital Epidemiologists of America. 2013;34(9):875–892. doi: 10.1086/672271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dominguez KL, Smith DK, Thomas V, et al. Updated guidelines for antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV—United States, 2016. 2016 doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6517a5. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/38856. Accessed 12 July 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Brown P, Merline JR, Levine D, Minces LR. Repeatedly false-negative rapid HIV test results in a patient with undiagnosed advanced AIDS. Annals of internal medicine. 2008;149(1):71–72. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-1-200807010-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stekler JD, Swenson PD, Coombs RW, et al. HIV testing in a high-incidence population: is antibody testing alone good enough? Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(3):444–453. doi: 10.1086/600043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.George CR, Robertson PW, Lusk MJ, Whybin R, Rawlinson W. Prolonged second diagnostic window for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in a fourth-generation immunoassay: are alternative testing strategies required? J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(11):4105–4108. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01573-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]