Abstract

Objective

To identify the demographic patterns of mortality, the time spent before death in the emergency department (ED), and the causes of fatal outcomes.

Methods

We performed a 5-year (01/01/2011 to 01/01/2016) retrospective analysis of all non-traumatic deaths in the ED of the UMHAT – Pleven. To extract the necessary information, we used the registers in the ED until the patients’ death.

Results

Among 156,848 patients in the study period, 381 died and the mortality rate was 2.4/100000. The male:female ratio was 1.48:1. The 71–80 years age group was the most affected. The mean (SD) age of patients who died in the ED was 69.9 ± 8.4 years. Most non-traumatic deaths (222 cases) were due to cardiovascular disease. Most patients (70.9%) died within 2.3 h after arrival. The factors contributing to mortality included poverty, transporting the patient to hospital too late, and a lack of developed care centres for terminally ill patients.

Conclusion

Most patients die within approximately 2 h after arrival at the ED. The main cause of death is acute myocardial infarction. Pulmonary embolism remains unrecognized in most patients (69%). Oncological pathology is among the main causes (7.4%) of mortality.

Keywords: Emergency department, death, autopsy, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism

Significance of the problem

The emergency department (ED) is the ‘face’ of any hospital and it provides details on the quality of patient care in the institution. The University Hospital for Active Treatment, “Dr Georgi Stranski”, which is located in the city of Pleven, is the main healthcare centre in the Northwest region of Bulgaria. The population in this region at the end of 1998 was 593,546 people or 7.2% of the population of Bulgaria. The latest data released by the World Health Organization show that cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death worldwide.1 Data from the National Statistical Institute shows a similar trend for Bulgaria.2 In 2010, approximately 110,000 deaths were registered in Bulgaria, of which 74,000 were caused by diseases of the cardiovascular system. In the emergency aid system, analysis of epidemiological indicators is one of the essential tools for process management.1,2,3 Outpatient and inpatient mortality have been studied,2–10,16 as well as mortality in EDs.12–14 However, there have been no studies on the causes of death in EDs in Bulgaria using data from autopsy reports and the definite cause of death.

Aim: This study aimed to identify the demographic patterns of mortality, the time spent before death in the ED, and the causes of fatal outcomes in an ED in Bulgaria.

Methods: We performed a 5-year retrospective analysis from 1 January, 2011 to 1 January, 2016 of all non-traumatic deaths in the ED of the University Hospital for Active Treatment in Pleven. To extract the necessary information, we used the registers in the hospital information system, outpatient journals, outpatient sheets, consultation sheets, and autopsy reports. From these, we collected information on the demographic indicators, causes of death, and the length of time from a patient’s admission in the ED until death. To analyse the data, we performed descriptive, variational, and graphical analysis methods, as well as tests for identifying dependencies using MS Excel (Data Analysis Tool Pack) and SPSS software products.

Outcomes and discussion

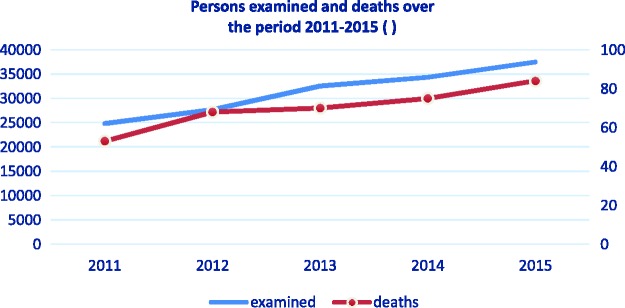

From 1 January, 2011 to 1 January, 2016 a total of 156,848 people were registered in the ED of the University Hospital “Dr. Georgi Stranski” in Pleven (Figure 1). Among these, 381 of them died, despite conducting resuscitation. The mortality rate was 2.4/100,000 people who were registered, which is a similar rate (2.7/100,000) to that in other studies.9,13

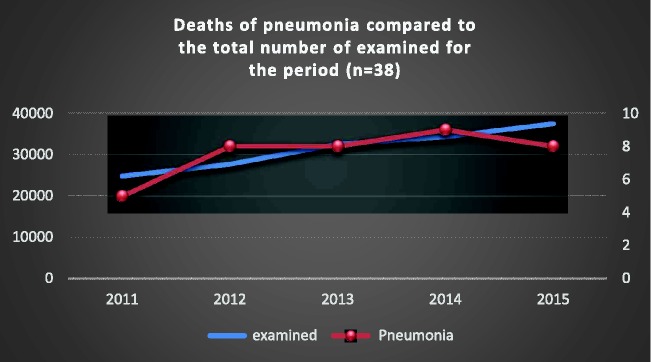

Figure 1.

Comparison between the persons examined and the deaths in the Emergency Department for the period 2011–2015. The chart shows clearly that the annual increase in the number of examinations correlate with the number of deaths. The two lines – of those examined and those who died are almost identical.

In 350 deaths, an autopsy was performed, and then each case was discussed at a clinical meeting in the ED to eliminate errors and optimize the protocols of behaviour. No autopsy was performed in only 31 people at the insistence of relatives.

In the 350 people who died and had an autopsy carried out, distribution by sex showed a prevalence of men. According to admission records, more than 2/3 of the patients were brought to the ED by Emergency Medical Aid Centre (EMAC) teams.

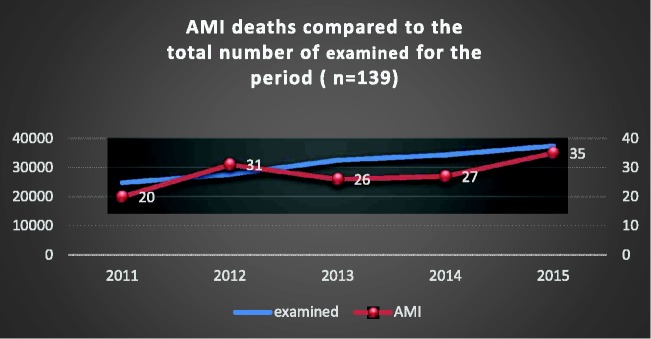

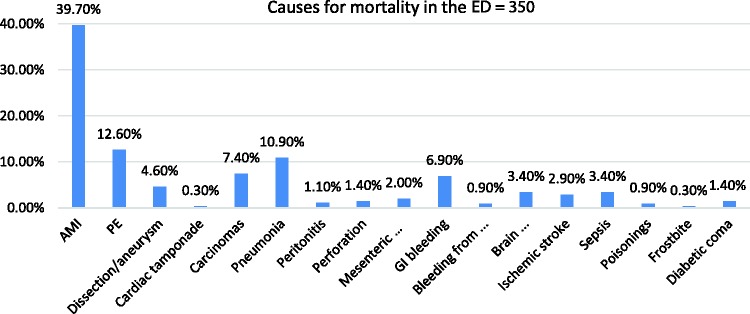

A total of 139 people died of acute myocardial infarction (AMI). AMI was the most common cause of sudden death in the ED and represented 39.7% of the total mortality in this department.

The mortality rate of AMI ranged from 20 to 35 deaths per year or approximately three per month (Figure 3). The average age of people who died from AMI was 73.1 years, with a male prevalence. The number of people brought to the ED by the EMAC team was almost twice that of those who sought help themselves. The average stay of these patients in the resuscitation area was 1:56 h. A total of 77 of these patients died after staying in the ED for shorter than 1 h and 28 who were brought by EMAC teams were in a state of clinical death.

Figure 3.

Comparison between the number of deaths from AMI and total mortality in the Emergency Department during the study period.

Compared with the total mortality in the department there was a direct correlation (p=1). The number of deaths due to AMI was constant (35% 39% of deaths in the ED) in each year of the 5-year period ( figure 3.)

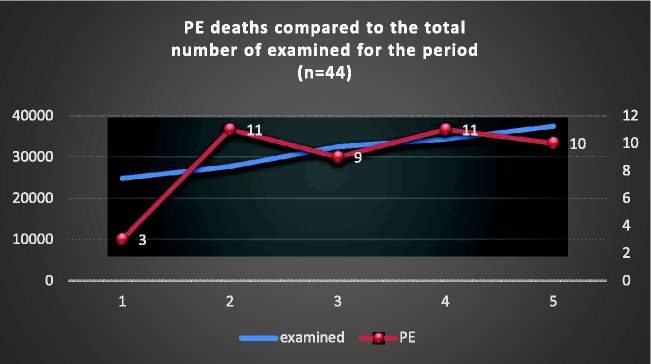

The second leading cause of death in the 350 people who were autopsied was pulmonary embolism (PE). A total of 44 (12.6%) people died because of PE during the study period (Figures 2 and 4).

Figure 2.

Graphic presentation of the main cause of death in autopsy reports of patients in the study period.

Figure 4.

Comparison between the number of deaths from PE and total mortality in the Emergency Department during the study period.

Patients with PE were mainly brought to the ED by EMAC teams (n = 34). Ten patients with PE sought help by their own means.

Unlike patients who died from AMI, in patients with PE, there was no significant difference in the distribution of sex. A total of 52% of patients with PE were men. The average age of patients who died from PE was 71 years. The youngest patient with PE was 37 years old and the oldest was 92 years. The average stay in the resuscitation area was 1:44 h. In 26 patients with PE, the visit to the ED was less than 1 h, and 20 of them were brought in a state of clinical death with immediate initiation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. In analysis of the autopsy reports and outpatient sheets, we observed that the teams in the ED suspected PE for only 14 deaths. In the other patients, the clinical diagnosis (observation) was different (Table 2).

Table 1.

Distribution of death by autopsy during the study period.

| Total number of deaths during the study period |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average age (y) | Sex |

Accepted by |

Average stay in the ED (h) | Percentage | ||||

| M | F | EMAC team | Community- acquired pneumonia | |||||

| AMI | 139 | 73.1 | 87 | 52 | 106 | 33 | 1:56 | 39.7% |

| PE | 44 | 71 | 23 | 21 | 34 | 10 | 1:44 | 12.6% |

| Community-acquired pneumonia | 38 | 67.3 | 29 | 9 | 25 | 13 | 2:18 | 10.9% |

| Carcinomas | 26 | 66.5 | 18 | 8 | 19 | 7 | 2:44 | 7.4% |

| GI bleeding | 24 | 70.4 | 10 | 14 | 20 | 4 | 1:34 | 6.9% |

| Dissection/aneurysm | 16 | 68.5 | 14 | 2 | 14 | 2 | 1:15 | 4.6% |

| Sepsis | 12 | 61 | 6 | 6 | 10 | 2 | 4:42 | 3.4% |

| Brain haemorrhage | 12 | 72.5 | 7 | 5 | 12 | 0 | 2:37 | 3.4% |

| Ischaemic stroke | 10 | 76.1 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 3:12 | 2.9% |

| Mesenteric thrombosis | 7 | 76 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 2:02 | 2.0% |

| Perforation | 5 | 70.7 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1:06 | 1.4% |

| Diabetic coma | 5 | 68.5 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 4:23 | 1.4% |

| Peritonitis | 4 | 79.2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3:56 | 1.1% |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 3 | 57 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0:28 | 0.9% |

| Poisoning | 3 | 54 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1:00 | 0.9% |

| Frostbite | 1 | 75 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1:35 | 0.3% |

| Cardiac tamponade | 1 | 83.1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0:40 | 0.3% |

| Total | 350 | 69.9 | 209 | 141 | 270 | 80 | 2:13 | |

Table 2.

Clinical diagnosis (before autopsy) of death from PE.

| Shock | PE | AMI | Pneumonia | Stroke | AHF | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 14 | 14 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 16 |

This finding suggested that there is an ineffective mechanism for recognizing the symptoms of the second most common cause of death in the ED. Non-use of some modern, fast, and non-invasive diagnostic methods, such as ultrasound, in the ED leads to confusion and misdiagnosis. The Canadian Emergency Ultrasound Society recommends that all emergency physicians take a course in emergency ultrasound. To obtain a certificate, they are required to perform at least 50 scans in each of the following four categories: the heart, for exclusion of pericardial tamponade; the aorta, for measuring its diameter to exclude aneurysm/dissection; the abdomen, to detect freely flowing liquid; and the uterus, to exclude ectopic pregnancy.11 Indirect ultrasound signs for right ventricular volume overload are important for diagnosing PE, and misapplying them indirectly leads to the results found in our study.

Generally, the group of cardiovascular diseases (Table 3), including AMI, PE, aortic dissection, cardiac tamponade, and ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke, was found in 222 (63%) patients among all deceased and autopsied patients in the ED during the study period. These data are similar to data from other studies that investigated the causes of death4,5 in EDs.

Table 3.

Number of deaths from cardiovascular disease over the study period.

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMI | 20 | 31 | 26 | 27 | 35 | 139 |

| PE | 3 | 11 | 9 | 11 | 10 | 44 |

| Aortic dissection | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 16 |

| Cardiac tamponade | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Brain haemorrhage | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 12 |

| Ischaemic stroke | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 10 |

Community-acquired pneumonia (Figure 5) was the third most common cause of death in the ED in our study. Despite all efforts, acute respiratory failure that occurred due to an inflammatory lung disease was the cause of death of 38 people over the 5-year period, or nearly 10% of all deaths in the ED.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the number of deaths from community-acquired pneumonia and total mortality in the Emergency Department during the study period.

The mortality rate of patients with community-acquired pneumonia ranged between 5 and 9 people per year, and the average age of death was 67.3 years. There was a high prevalence of male sex in these patients, comprising 29 men and only nine women. The average stay of a patient in the resuscitation area until the time of death was 2:18 h.

Among the main causes of mortality, 7.4% of the deaths in the ED were due to advanced carcinomas (Table 4). A lack of comprehensive care for patients with cancer in Bulgaria forces the relatives of these patients to seek help in the ED.

Table 5.

Number of relatively rare causes of deaths in the Emergency Department by year.

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aortic dissection | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 16 |

| Bleeding of gynaecological origin | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Brain haemorrhage | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 12 |

| Ischaemic stroke | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 10 |

| Sepsis | 6 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 12 |

| Poisoning | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Diabetic coma | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

Table 4.

Distribution of death from other causes in the ED over the study period.

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumonia | 5 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 38 |

| Carcinomas | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 13 | 26 |

| Peritonitis | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Perforation | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Mesenteric venous thrombosis | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 7 |

| GI bleeding | 8 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 24 |

| Total abdominal diseases | 9 | 8 | 11 | 6 | 6 | 40 |

During the 5-year study period, 40 people died of acute diseases of the gastrointestinal tract, comprising 11% of the total mortality.

The most common cause of this mortality was GI bleeding in 24 patients. The average age of these patients was 70.4 years, with a female prevalence (58%). The average stay in the resuscitation area was 1:34 h.

A total of 0.9% to 4.6% of deaths were due to other causes.

Aortic dissection, ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke, and sepsis were relatively similar in prevalence, with 10 to 16 cases in the 5-year study period.

The least common causes of death in the ED were frostbite in one patient (man, 75 years old) who died in 2011, and cardiac tamponade in one patient (woman, 83 years old) who died in 2013 with the clinical picture of cardiogenic shock.

The monthly distribution of deaths in the ED showed a peak of deaths in the spring and autumn to winter seasons. This finding is similar to a study of mortality in the EDs in Bulgaria.4

Conclusions

Most patients (70.9%) died within 2.3 h after arrival at the ED, with the majority (77%) being brought to the ED by EMAC teams.

The observed mortality shows similar results to some previous studies.7,13

Mortality among older patients is prevalent in the ED, and men are more vulnerable.

The leading cause of death is cardiovascular disease, and the most common cardiovascular disease is AMI.

Pulmonary embolism remains unrecognized in the majority of cases.

Not using some modern, rapid, and non-invasive diagnostic methods, such as ultrasound, in EDs leads to confusion and misdiagnosis. The Canadian Emergency Ultrasound Society recommends that all emergency physicians take a course in emergency ultrasound. To obtain a certificate, they are required to perform at least 50 scans in each of the following four categories: the heart, to exclude pericardial tamponade; the aorta, to measure its diameter to exclude aneurysm/dissection; the abdomen, to detect freely flowing liquid; and the uterus, to exclude ectopic pregnancy.

One of the main causes of mortality is oncological pathology. A lack of comprehensive care for patients with cancer in Bulgaria forces the relatives of these patients to seek help in the ED where they die.

Discussing cases at clinical meetings in the ED, and comparing the clinical and pathological-anatomical diagnosis contribute to eliminating errors and optimizing the protocols of behaviour.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Medical University – Pleven, grand number is 000405689.

References

- 1.World Health Organization.Mortality and burden of disease from unhealthy environments, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2016/deaths-attributable-to-unhealthy-environments/en/, (15 march 2016).

- 2.National Statistical Institute (NSI).Mortality by cause, sex, statistical regions and districts, Statistical Yearbook 2015, http://www.nsi.bg/en/content/5621/deaths-causes-sex-and-statistical-regions, (29.06.2016).

- 3.Vodenitcharov C. Modern health policy is health policy based on the evidence. magazine. Health Policy and Management, 2009, 4, 3–8.

- 4.Yordanova E, Petkova L and Nedelkova M. Health 2013 Ed. Of the Demographic and Social Statistics, Department Statistics of health, justice and culture; ISSN 1313–1907.

- 5.Hubanov N. Analysis of the recorded 24-hour mortality in emergency departments, Health and Science, Issue 2 (018), 2015.

- 6.Shipkovenska, E., M. Vukov, L. Georgieva. Descriptive epidemiological studies. Modern epidemiology, Konkvista, Varna 1997, I: 27–39, 174–186.

- 7.Beckett MW, Longstaff PM, McCabe MJ, et al. Deaths in three accident and emergency departments. Arch Emerg Med 1987; 4: 227–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker M, Clancy M. Can mortality rates for patients who die within the emergency department, within 30 days of discharge from the emergency department, or within 30 days of admission from the emergency department be easily measured? Emerg Med J 2006; 23: 601–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cummings P. Cause of death in an emergency department, The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, Elsevier September 1990; 8: 379–384. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Donath S, Davidson A, Babl FE. A primer for clinical researchers in the emergency department: Part V: How to describe data and basic medical statistics. Emerg Med Australas 2013; 25: 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ekere AU, Yellowe BE, Umune S. Mortality patterns in the accident and emergency department of an urban hospital in Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract 2005; 8: 14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumka G, Filanovsky Y. Should emergency physicians be using a more extensive form of ultrasound to assess non-traumatic hypotensive patients? CJEM 2006; 8: 47–49. doi: 10.1017/S1481803500013397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mushtaq F, Ritchie D. Do we know what people die of in the emergency department? Emerg Med J 2005; 22: 718–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roller JE, Prasad NH, Garrison HG, et al. Unexpected emergency department death: incidence, causes, and relationship to presentation and time in the department. Ann Emerg Med 1992; 21: 743–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quigley M, Burton J. Evidence for cause of death in patients dying in an accident and emergency department. Emerg Med J 2003; 20: 349–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radev Vl R. Nosocomial infections in intensive care with a central general hospital profil.Avtoreferat of dissertation for Ph.D. degree, Pleven, 2016.