Abstract

Workers in the Arctic open-pit mines are exposed to harsh weather conditions. Employers are required to provide protective clothing for workers. This can be the outer layer, but sometimes also inner or middle layers are provided. This study aimed to determine how Arctic open-pit miners protect themselves against cold and the sufficiency, and the selection criteria of the garments. Workers’ cold experiences and the clothing in four Arctic open-pit mines in Finland, Sweden, Norway and Russia were evaluated by a questionnaire (n=1,323). Basic thermal insulation (Icl) of the reported clothing was estimated (ISO 9920). The Icl of clothing from the mines were also measured by thermal manikin (standing/walking) in 0.3 and 4.0 m/s wind. The questionnaire showed that the Icl of the selected clothing was on average 1.2 and 1.5 clo in mild (−5 to +5°C) and dry cold (−20 to −10°C) conditions, respectively. The Icl of the clothing measured by thermal manikin was 1.9–2.3 clo. The results show that the Arctic open-pit miners’ selected their clothing based on occupational (time outdoors), environmental (temperature, wind, moisture) and individual factors (cold sensitivity, general health). However, the selected clothing was not sufficient to prevent cooling completely at ambient temperatures below −10°C.

Keywords: Cold, Thermal sensations, Protective clothing, Questionnaire study, Thermal manikin, Arctic mining

Introduction

Mining can be divided into two common excavation types: open-pit or surface mining and underground mining. Rising demands for minerals have accelerated to open new mines or even reopen already closed mines all over the world. Demands to open new mines also in the Arctic regions are increasing because the Arctic holds abundant mineral resources and global warming is expected to shorten the shipping routes through the northern passages.

Working conditions in the Arctic open-pit mines are dependent on weather conditions with low temperatures, and long periods of the darkness in wintertime. The cold ambient conditions impair physical and mental performance1) and increase risks of occupational accidents directly by cooling the workers and indirectly e.g. by slippery surfaces2). Human body responds to cold exposure by decreasing circulation in skin, arms and legs to prevent heat loss, which further facilitates the cooling. Hands and feet are especially vulnerable to cooling as their own heat production is minimal and therefore their heat balance depends almost totally on the heat transported by circulation. Cooling of hands results at first sensation of cold and if cooling continues, a decrement in manual performance and eventually cold pain and even loss of sensations3, 4). Feet react to cooling by the same way as hands, but their rewarming time is usually even longer5).

According to Fanger6) there are three requirements for a person’s whole-body thermal comfort: 1) the body is in heat balance, 2) the sweat rate is within comfort limits and 3) the mean temperature is within comfort limits. In addition to these, the fourth condition is the absence of local thermal discomfort. People can ensure comfort and performance by behavioural means (behavioural thermoregulation) by, for example, moving to more desirable thermal conditions, adjusting clothing, increasing or decreasing physical activity, seeking shelter or changing posture.

Working in open-pit mines in the Arctic region requires protection against cold and high wind speed. Varying ambient conditions and work load create problems in the adjustment of the thermal insulation of clothing while working. Similarly, work load in mines fluctuates from rest to light and heavy work. Moreover, periods of heavy work may cause occasionally sweating and moisture accumulation into clothing. Gavhed et al.7) have stated that at equal energy expenditures continuous work implied higher mean skin temperature and warmer thermal sensation than during intermittent work.

The thermal protective properties of clothing are decreased due to influence of body movement, wind and moisture depending on permeability properties of clothing materials8, 9, 10, 11). It is also recognized that material selection and clothing size effect on the thermal protective properties and comfort of the clothing11, 12).

Employers are required to provide protective clothing for workers. Usually the companies provide for outdoor work at least the outer clothing layer. Some companies also offer inner or middle clothing layers for voluntary use. However, workers use their own selection of winter garments underneath the outer clothing. Outdoor workers, such as open-pit miners, in the Arctic are expected to be familiar with the harsh weather conditions and know how to protect themselves in the cold. Earlier studies in cold-climate open-pit mines have not provided information, whether the used protective garments are sufficient and the clothing is adjusted according to environmental factors, duration of the work period, intensity of the work and individual factors.

The aims of this study were to find out, how Arctic open-pit mine workers protect themselves against cold in real work environments, and the sufficiency of the selected protective clothing against the harsh weather conditions. The study also evaluates the selection criteria of garment used in wintertime among open-pit miners.

Subjects and Methods

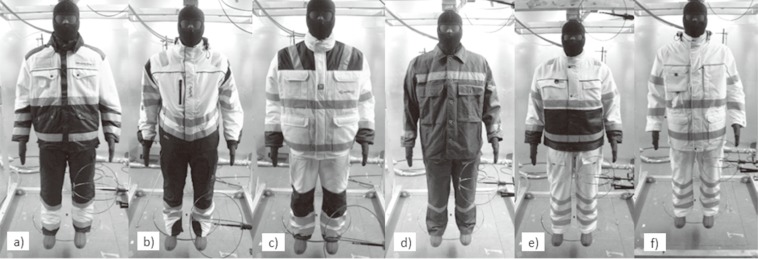

Thermal insulation of the clothing by thermal manikin

The measured clothing ensembles including garment, that company provides to the workers, were obtained from four different Arctic open-pit mines from Finland, Norway, Russia and Sweden. Thermal insulation of six unused protective clothing ensembles (Table 1, Fig. 1) were measured in climatic chamber by thermal manikin. In case the company did not provide inner or middle layers to the workers, reference clothing according to the standard for cold protective clothing13) was used.

Table 1. The measured mine workers’ clothing ensembles from four countries.

| Layer | Finland | Norway 1 | Norway 2 | Russia | Sweden 1 | Sweden 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inner | Knit: PES 96%, EL 4% | Knit: WO 50%, Protex M 50% (FR) | Knit: WO 50%, Protex M 50% (FR) | EN 342 Ref B | Knit: WO 70%, PP 30% | Knit: WO 70%, PP 30% |

| Middle | EN 342 Ref B | EN 342 Ref B | EN 342 Ref B | EN 342 Ref B and quilted vest | PES 100%, EN 342 (0.286 (B) (1.85 clo) | PES 100%, EN 342 (0.286 (B) (1.85 clo) |

| Outer | Jacket/trousers: Outer: PES 70%, CO 30%; Lining: PES 100% | Jacket/trousers: Outer/ Lining/ Padding: PES 100% | Jacket/ trousers: Main: PES 45%, CO 55%, Contrast: PES 60%, CO 40%, Shoulder: PES 100% coated with PU, Lining: PES 100% | Thin jacket and trousers | Jacket, short: 100% PES, terry knit lining Trousers: Outer: PES 100%, PU laminated membrane, Lining: PES quilt 100% |

Jacket, long: PES 100% (outer, quilt, lining), Trousers: Outer: PES 100%, PU laminated membrane, Lining: PES quilt 100% |

CO: Cotton, EL: Elastane, FR: Fire retardant, PES: Polyester, WO: Wool, PP: Polypropylene, PU: Polyurethane.

Fig. 1.

Clothing ensembles of open-pit mine workers from four different countries: a) Finland, b) Norway 1, c) Norway 2, d) Russia, e) Sweden 1, and f) Sweden 2.

Thermal insulation of the clothing ensembles were measured by using an aluminum thermal manikin consisting of 20 segments in a climate chamber14). The measurements were divided into two parts: dry resultant effective thermal insulation with walking thermal manikin (Icler) according to the standard for cold protective clothing13) and effect of wind on heat loss with standing thermal manikin. The first part of the measurements were performed according to standards EN 34213) (serial) and EN ISO 1583115) at ambient temperature of +10°C with moving thermal manikin. The second part evaluated effect of the wind on static total thermal insulation (It, serial) measured by the static thermal manikin at temperature of −10°C in calm (0.3 m/s) and windy (4.0 m/s) conditions. The thermal insulation values in this paper are given in clo-units. 1 clo in SI-units equals to 0.155 m2K/W.

Questionnaire study

A questionnaire study16, 17) was directed to the employees among workers with duties consisting mainly of outdoor work in four open-pit mines located in Northern Finland, Sweden, Norway, and Russia. The questions focused only on outdoor clothing. The data was collected in period from November 2012 to November 2013. Burström et al.17) have described in detail the questionnaire that was part of the MineHealth project18).

The questionnaire was carried out in written form either in national language (Finnish, Swedish, Norwegian, or Russia) or in English. The data presented in this study is part of the pooled database obtained from the four countries (n=1,323).

One purpose of the questionnaire was to collect similar data sets by using identical data collection instruments at the four study sites. There were some discrepancies between the data sets, e.g. the choice of questions included in the questionnaire, the phrasing of questions and the categorization of answers.

The criteria for including data in this study was that data from at least three countries were present, and that formulation of questions and categorization of answers were identical. Slight differences concerning the latter criteria were accepted but pointed out as comments. Some questions in the database were omitted in this report since they did not meet the criteria mentioned above.

Adequacy of cold protective clothing

The questionnaire study evaluating open-pit miners’ use of different garments in different ambient conditions was asked only in three out of four study sites: Northern Finland, Sweden and Russia (total n=1,104).

Basic thermal insulation (Icl) of the reported clothing ensembles for different ambient conditions was estimated based on a summation method of the insulation of individual garments using the following empirical Equation 119):

| (1) |

where Iclu is the effective thermal insulation of the individual garments making up the ensemble, in clo. The used Iclu values for estimation is presented in the Table 2.

Table 2. Thermal insulation values (Iclu) for individual garments based on the standard ISO 992019).

| Garment description | Iclu (clo) |

|---|---|

| Inner layer | |

| Shirt, short sleeved | 0.09 |

| Shirt, long sleeved | 0.12 |

| Pants, short | 0.03 |

| Pants, long | 0.10 |

| Middle layer | |

| Shirt, thin | 0.20 |

| Shirt, thick (woollen, college, fleece or comparable) | 0.35 |

| Pants, middle layer | 0.25 |

| Tights | 0.03 |

| Outermost layer | |

| Jacket, thin | 0.26 |

| Jacket, thick | 0.40 |

| Trousers, thin | 0.25 |

| Trousers, thick | 0.35 |

| Thermal overall or thermo clothing | 0.55 |

| Headgear | |

| Cap, hat, balaclava or comparable | 0.01 |

| Warm winter cap | 0.03 |

| Scarf | 0.01 |

| Gloves | |

| Gloves/mittens, thin | 0.05 |

| Gloves/mittens, thick | 0.08 |

| Gloves/mittens, thermal or leather | 0.11 |

| Socks and shoes | |

| Socks, thin | 0.02 |

| Socks, second thin | 0.02 |

| Socks, thick (woolen or comparable) | 0.05 |

| Woollen footwraps | 0.10 |

| Safety shoes, summer | 0.04 |

| Safety shoes, winter | 0.10 |

| Safety boots, rubber | 0.10 |

Data analyses

The data were analysed statistically using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). The SPSS enabled direct analysis of each question and cross-tabulation of the data. Cross tabulation between the estimated basic thermal insulation was performed between following questions in the questionnaire: age, gender, weight, calculated body mass index (BMI), general health, time spent outdoors or unheated places (h/d), experienced problems with wind in cold, clothing wetness, thermal sensations in mild or wet cold, and dry cold, and experienced problems with compatibility of different protective equipment. BMI was calculated according the equation BMI=weight/height2 (kg/m2). The standard weight categories associated with BMI ranges are as follows: BMI under 18.5 (underweight), BMI 18.5–24.9 (normal weight), BMI 25.0–29.9 (overweight), and BMI 30.0 and above (obese). The data is presented as mean values and standard deviation (SD). Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to measure the strength of the association between the variables to each other. The level of significance in all the statistical tests was set to be p<0.05.

Results

Thermal insulation of the clothing measured by thermal manikin

The resultant effective thermal insulation (Icler) measured according to the standard for cold protective clothing13) by moving thermal manikin was 1.9–2.3 clo (0.29–0.36 m2K/W). The standard set the lowest limit for cold protective clothing to have thermal insulation of 2 clo (0.31 m2K/W). Wind speed of 4.0 m/s decreased the total thermal insulation (It) by 26–30% as presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Thermal insulation values (serial) measured by walking and standing thermal manikin in wind speeds of 0.3 and 4.0 m/s.

| Thermal insulation (Clo) | Effect of wind while standing on It (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Icler EN 34213) |

It Calm (0.3 m/s), Standing* |

It Wind (4.0 m/s), Standing** |

||

| Finland | 2.34 | 3.97 | 2.55 | −35.7 |

| Norway 1 | 1.97 | 3.85 | 2.61 | −32.2 |

| Norway 2 | 2.21 | 3.24 | 2.35 | −27.4 |

| Russia | 1.88 | 3.28 | 2.37 | −27.6 |

| Sweden 1 | 2.04 | 3.76 | 2.68 | −28.7 |

| Sweden 2 | 2.07 | 3.78 | 2.82 | −25.5 |

| Mean | 2.08 | 3.65 | 2.57 | −29.5 |

*Thermal insulation of boundary air layer (Ia)=0.58 clo, **Ia=0.19 clo

Questionnaire study

General information of the respondents is given in the Table 4. On an average BMI indicated miners to be overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2). Workers in the open-pit mines were mainly men (92%). Female respondents (8% from total) were only working in the open-pit mines in Finland, Norway and Sweden.

Table 4. General information of the respondents from the four studied open-pit mines.

| Number of answers | Age (yr) | BMI (kg/m2) | Female workers n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finland | 199 | 35.7 ± 10.0 | 27.1 | 37 (19%) |

| Norway | 101 | 41.7 ± 12.8 | 28.6 | 18 (18%) |

| Russia | 870 | 40.6 ± 10.9 | 27.2 | 0 (0%) |

| Sweden | 153 | 39.9 ± 11.5 | 25.9 | 57 (37%) |

| Total | 1,323 | 39.9 ± 11.1 | 27.1 | 112 (8%) |

Cold exposure and thermal sensations

An average daily outdoor working time was 4.3 h (Finland 2.9 h, Norway 2.8 h, Russia 5.0 h, Sweden 3.1 h).

Thermal sensations of the whole body, fingers and toes of the Arctic open-pit miners in mild or wet cold and dry cold conditions are presented in the Table 5.

Table 5. Experienced thermal sensations of whole body, fingers, and toes during work in the winter time in mild or wet (Ta from −5 to +5°C) and dry cold (Ta from −20 to −10°C). Number and percentage of the responds.

| In mild or wet cold (temp. appr. −5…+5°C) | In dry cold (temp. appr. −20…−10°C) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finland | Norway | Russia | Sweden | Finland | Norway | Russia | Sweden | |

| Whole body | ||||||||

| warm or hot | 30 (16%) | 9 (15%) | 114 (15%) | 18 (20%) | 5 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 33 (5%) | 7 (8%) |

| neutral | 146 (80%) | 38 (63%) | 459 (61%) | 66 (73%) | 98 (54%) | 25 (56%) | 298 (49%) | 55 (61%) |

| cool | 7 (4%) | 12 (20%) | 145 (19%) | 5 (6%) | 56 (31%) | 14 (31%) | 193 (32%) | 24 (27%) |

| cold | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 41 (5%) | 2 (2%) | 22 (12%) | 5 (11%) | 87 (14%) | 4 (4%) |

| Fingers | ||||||||

| warm or hot | 15 (8%) | 6 (10%) | 53 (10%) | 12 (13%) | 6 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 17 (4%) | 4 (4%) |

| neutral | 136 (75%) | 35 (60%) | 288 (52%) | 60 (65%) | 55 (31%) | 14 (32%) | 162 (37%) | 44 (48%) |

| cool | 26 (14%) | 14 (24%) | 134 (24%) | 18 (20%) | 71 (39%) | 19 (43%) | 137 (31%) | 27 (29%) |

| cold | 5 (3%) | 3 (5%) | 75 (14%) | 2 (2%) | 48 (27%) | 10 (23%) | 120 (28%) | 17 (19%) |

| Toes | ||||||||

| warm or hot | 24 (13%) | 6 (10%) | 65 (12%) | 10 (11%) | 7 (4%) | 3 (7%) | 21 (5%) | 4 (4%) |

| neutral | 132 (72%) | 41 (71%) | 290 (55%) | 66 (72%) | 67 (37%) | 16 (36%) | 180 (44%) | 44 (48%) |

| cool | 25 (14%) | 9 (16%) | 112 (21%) | 13 (14%) | 63 (35%) | 17 (39%) | 123 (30%) | 31 (34%) |

| cold | 2 (1%) | 2 (3%) | 61 (12%) | 3 (3%) | 44 (24%) | 8 (18%) | 90 (22%) | 12 (13%) |

Wind was experienced as a problem in cold as “often” by an average 30% of the respondents (Finland 17%, Norway 8%, Russia 37% and Sweden 24%), “sometimes” by 44% (Finland 52%, Norway 35%, Russia 42% and Sweden 50%) while an average 26% (Finland 31%, Norway 58%, Russia 21% and Sweden 26%) did not have problems related to wind in the cold.

Cold protective clothing

Workers listed garments what they used in mild wet cold (ambient temperature, Ta approximately −5 to +5°C) and dry cold (−20 to −10°C). The results showed that lighter clothing, such as short sleeve shirt, thin shirt, thin jacket and trousers, was used more often in mild ambient temperatures. Whereas, in dry cold warmer garments, such as long sleeved shirt, long legged pants, thick shirt, middle pants, thick jacket and trousers, were common. Thermal overall was used approximately by 16% in dry cold temperatures.

The most common headgear in both ambient conditions was a hat, cap, balaclava or comparable. Less than 40% of the workers used warm winter cap in the dry cold conditions. The warm winter cap was often too large to use together with required helmet. The headgear may also cause conflict when used together with hearing protection. Approximately 16% did not use any headgear in mild wet cold. The question excluded helmet, which is required in all operational working place and it also provides some thermal protection.

The results showed clearly that thinner gloves were used in mild wet temperatures, whereas thicker gloves or thermal gloves were used in dry cold conditions. Only 7 and 2% of the workers were working bare-handed in mild and cold temperatures, respectively. In addition, the protection of the feet was increased when ambient temperature decreased.

The reported garments were used to calculate the basic thermal insulation (Icl) using Equation 1. The Icl of the open-pit miners’ winter clothing was on an average 1.22 clo (0.186 m2K/W) and 1.47 clo (0.233 m2K/W) in mild wet cold (Ta from −5 to +5°C) and dry cold (Ta from −20 to −10°C) conditions, respectively. The Table 6 presents the Icl values in different countries and between genders.

Table 6. Basic thermal insulation, Icl, in the mild or wet (Ta from −5 to +5°C) and dry cold (Ta from −20 to −10°C) conditions calculated according to ISO 992019). Mean Icl (Clo) ± Standard deviation (SD).

| Basic thermal insulation, Icl (Clo), ± SD | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=1,104) | Finland (n=170) | Russia (n=859) | Sweden (n=75) | Male (n=1,062) | Female (n=42) | |

| Wet, mild cold | 1.22 ± 0.43 | 1.25 ± 0.35 | 1.22 ± 0.44 | 1.10 ± 0.34 | 1.22 ± 0.43 | 1.20 ± 0.31 |

| Dry cold | 1.47 ± 0.50 | 1.71 ± 0.46 | 1.41 ± 0.50 | 1.54 ± 0.40 | 1.46 ± 0.50 | 1.64 ± 0.39 |

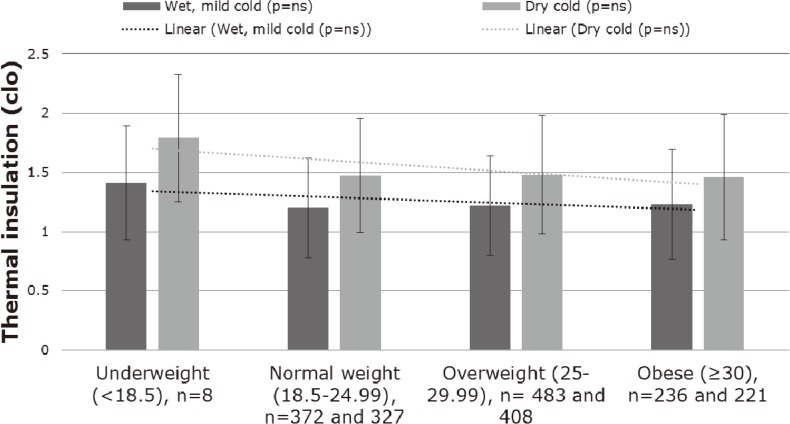

Relationship between clothing and personal and occupational characteristics

There were no statistically significant findings between selected clothing thermal insulation and age, gender, weight or BMI. However, workers with low or normal BMI (BMI <25) had tendency to select higher Icl than workers with high BMI (>25), as illustrated in Fig. 2. Similar trend was not seen between the selected Icl and body weight.

Fig. 2.

The selected clothing basic thermal insulation (±SD) in relation to different BMI levels (p=ns) in mild or wet (Ta from −5 to +5°C) and dry cold (Ta from −20 to −10°C).

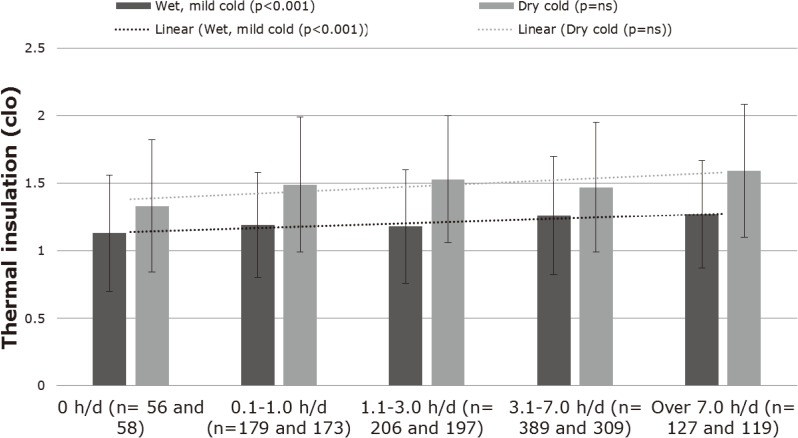

The results showed that the higher Icl was selected if working time outdoors or unheated buildings or machines was long in mild or wet cold conditions (p<0.001) and similar tendency was perceived in dry cold conditions (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The selected clothing basic thermal insulation (±SD) in relation to cold exposure time during work day in mild or wet (Ta from −5 to +5°C) and dry cold (Ta from −20 to −10°C).

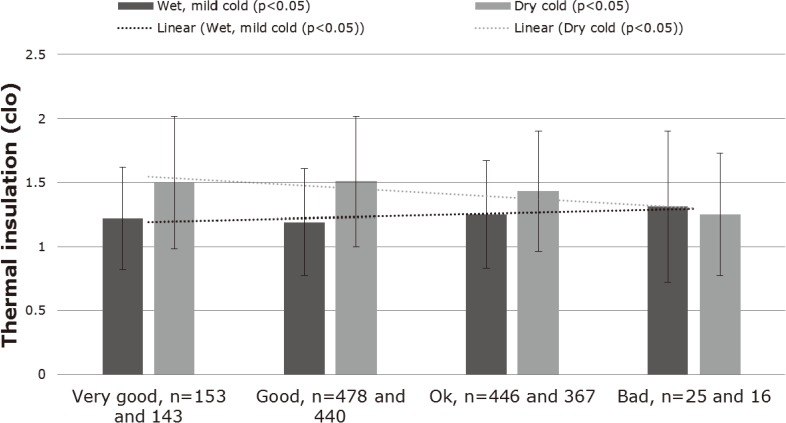

The general health of the workers had significant influence on the selected Icl (p<0.05) both in mild or wet and dry cold conditions (Fig. 4). In the mild or wet cold conditions workers had slightly lower Icl when they felt their general health being “very good” or “good” and lower when having “bad” feeling for their general health. In the dry cold conditions the level of Icl selected was opposite.

Fig. 4.

The selected clothing basic thermal insulation (±SD) in relation to experienced general health of the workers in mild or wet (Ta from −5 to +5°C) and dry cold (Ta from −20 to −10°C) (p<0.05).

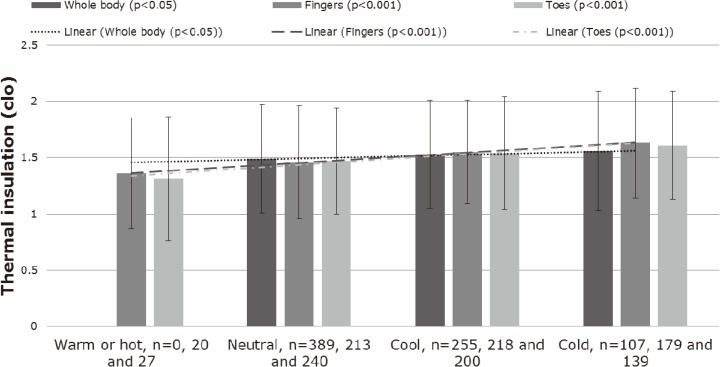

The Fig. 5 illustrates how the selected clothing thermal insulation was related to the thermal sensation of the whole body, fingers and toes in dry cold conditions (p<0.05). The Icl varied depending on the thermal sensations: The colder sensation of the whole body, fingers or toes, the higher Icl.

Fig. 5.

The selected clothing basic thermal insulation (±SD) in relation to thermal sensations on whole body, fingers and toes in dry cold conditions (Ta from −20 to −10°C).

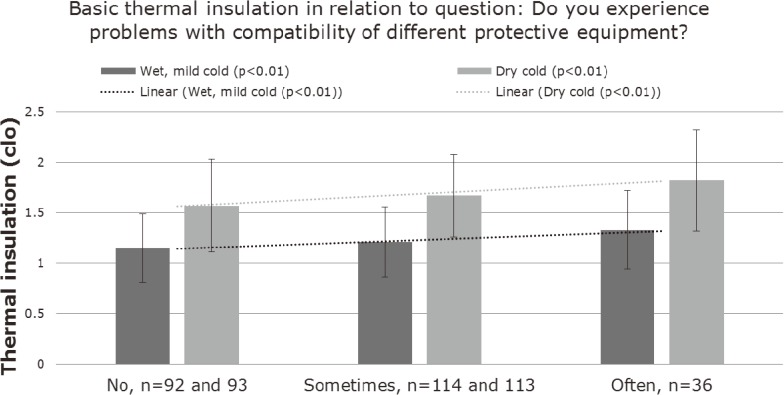

The questionnaire studied workers’ experience on compatibility of the personal protective equipment (PPE). The Fig. 6 illustrates that if the higher Icl was selected, also compatibility of different PPE was experienced to cause problems more often.

Fig. 6.

The selected clothing basic thermal insulation (±SD) in relation to experienced problems with compatibility of different protective equipment in mild or wet (Ta from −5 to +5°C) and dry cold conditions (Ta from −20 to −10°C) (p<0.01).

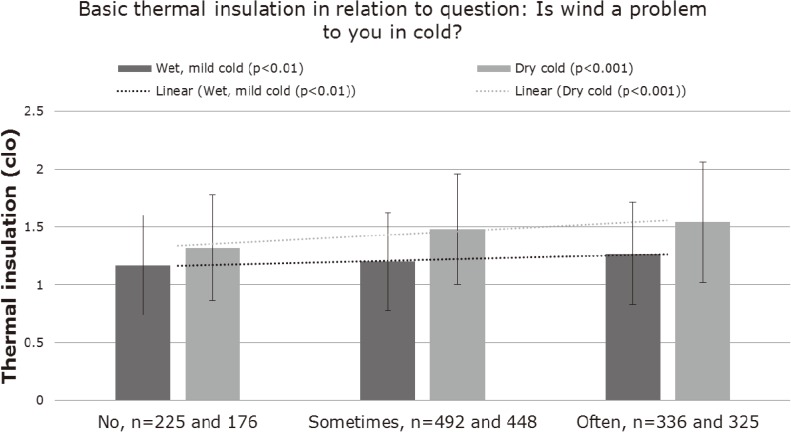

Relationship between clothing and wind and moisture

In case, wind was experienced often as a problem, the selected Icl was significantly (p<0.01) higher both in mild or wet and dry cold conditions as illustrated in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

The selected clothing basic thermal insulation (±SD) in relation to if wind was experienced as a problem while working in the cold.

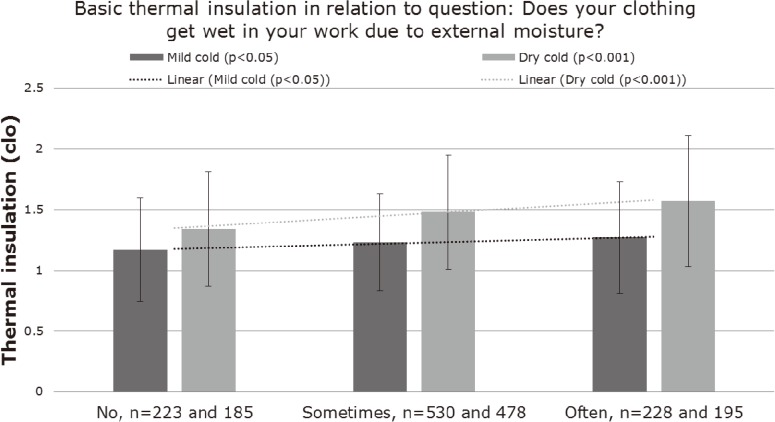

Clothing was experienced to get wet “often” by an average 21% of the respondents (Finland 15%, Norway 4%, Russia 26% and Sweden 11%), “sometimes” by 55% (Finland 55%, Norway 59%, Russia 56% and Sweden 43%) and clothing was rated not to get wet by 24% of the respondents (Finland 30%, Norway 37%, Russia 17% and Sweden 46%) during the work.

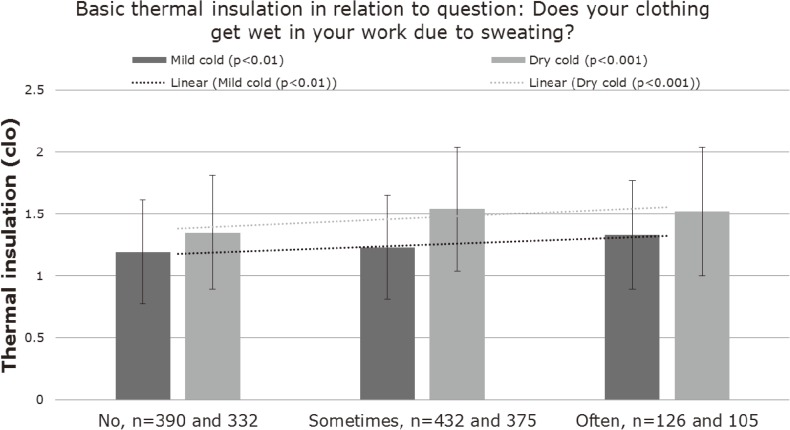

Clothing wetness had significant effect on clothing selection in mild or wet cold conditions (p<0.01): The higher Icl was selected, the more often clothing was experienced to get wet. Figures 8 and 9 show the Icl based on the cause of the moisture in the clothing, whether it became from external source or sweating. Statistical significance was found in both cases (p<0.05).

Fig. 8.

The selected clothing basic thermal insulation (±SD) in relation to if the clothing was experienced to get wet due to external moisture while working in the cold.

Fig. 9.

The selected clothing basic thermal insulation (±SD) in relation to if the clothing was experienced to get wet due to sweating while working in the cold.

Discussion

This study determines the ability of the Arctic open-pit mine workers to select and adjust their cold protective garments in actual work conditions to sustain thermal comfort. The results showed that the selection of winter clothing was affected by working time outdoors or unheated sites, environmental conditions, sensitivity to cold and general health. However, selected clothing was not sufficient to prevent cooling at ambient temperatures below −10°C.

The thermal sensation “cool” may be experienced unpleasant, but it is not considered to cause harmful cooling or frostbites. If worker has “cold” thermal sensation the risk of harmful cooling should be considered. The questionnaire study revealed that the “cold” thermal sensations increased when ambient temperature was lower than −10°C.

Adequacy of cold protective clothing

The Laboratory measurements by thermal manikin resulted that five out of six unused work clothing ensembles from four different open-pit mines reached the limit value (2 clo) of the standard for cold protective clothing13). The lowest Icl value was provided by clothing used in Russian mine and it did not consist of insulation padding or lining, but consisted of thermal vest.

Based on the questionnaire the selected garment combinations were used to calculate the basic thermal insulation accordance with the standard ISO 992019). The basic thermal insulation value does not include boundary air layer and thus it is expected to correspond with real clothing insulation value. The mean values of the Icl were 1.22 clo (0.186 m2K/W) in mild or wet cold (Ta from −5 to +5°C) and 1.47 clo (0.233 m2K/W) in dry cold conditions (Ta from −20 to −10°C). According to Insulation Required –index (IREQ)20) the calculated mean Icl is sufficient for long term (8 h) moderate work (150 W/m2) in mild cold conditions (0°C), whereas the mean Icl selected for dry cold conditions (−15°C) requires heavier work (190 W/m2) to be performed to maintain thermal balance for long period (8 h). Because the outdoor working periods were usually interrupted every 2–3 h by breaks either indoors or in vehicles, only peripheral skin temperatures (especially in fingers) decreased to the level causing complains.

Selection criteria of cold protective clothing

The results of the cross-tabulation of the basic thermal insulation between age, gender, weight or BMI did not show statistical significance. However, female workers selected warmer clothing especially in dry cold conditions, but the number of female respondents was low (8% of all respondents). Nevertheless, it seems that workers with higher BMI (above 25) choose lower Icl.

Working time outdoors or in unheated buildings or machines influenced on clothing selection: The longer is the cold exposure, the higher is the selected clothing insulation. This shows that workers can estimate the need for cold protection according to the duration of the work.

Workers’ experience of their general health had also relation to clothing selection (p<0.05). In the mild conditions workers had lower Icl when they felt their general health being “very good” or “good” and higher when having “bad” feeling for their general health. In cold conditions, level of Icl was selected the opposite way. It seems that workers having better general health adjusted their clothing more than workers experiencing their general status worse. On the other hand, workers with reduced general health may not be working long periods outdoors due to physically heavy tasks in the field.

Interestingly, if thermal sensation was perceived cold on the whole body, fingers or toes, the higher Icl of the clothing was selected (p<0.05). Similar correlation was found between the selected Icl and experienced problems with the exposure to wind (p<0.01) and moisture (p<0.01) at work. This refers that Arctic open-pit mine workers recognize their sensitivity to cold and they attempt to adjust and compensate it by additional clothing. Regardless, the higher Icl was not sufficient to prevent cooling of the whole body, fingers and hands in ambient temperature lower than −10°C. Higher Icl creates thicker clothing that may hinder and limit the movements of hands and arms and thus decrease the physical performance at work and increase metabolic heat production.

Clothing wetness due to sweating had also significant correlation with clothing selection (p<0.01) in mild and cold conditions. If clothing got often wet due to sweating, the higher Icl was selected. Taking into account the knowledge of open-pit miners’ work tasks (the physical work load variation and moving between warm and cold ambient temperatures), the reason for sweating may be that workers are not able to adjust the clothing in changing situations at work.

The use of other PPE may be one limiting factor preventing to add enough thermal protective clothing at work in the cold. The results show that when the higher Icl was selected, more problems in compatibility of different PPE was also experienced (p<0.01).

Conclusions

In conclusion, Arctic open-pit miners’ selected their winter clothing based on occupational features (working time outdoors or unheated sites), environmental conditions (temperature, wind and moisture) and individual factors (sensitivity to cold and general health). Workers who suffered the cold, wind or moisture, or worked long periods outdoors, also selected warmer clothing. However, clothing selection was not sufficient to prevent cooling of whole body, fingers or toes in colder ambient temperatures than −10°C. Use of adequate clothing for current conditions may not be possible due to 1) clothing thickness and its limitations on work, 2) use of several PPE at the same time, or 3) continuous variation of work load or ambient temperature.

The results suggest that employers should provide sufficient cold protective clothing and also guidance for the workers in the Arctic conditions. Possibilities of smart technology and wearable heating systems could be considered to provide additional protection against cold without increasing thickness or weight of the clothing especially for workers who are sensitive to cold or have cold-related problems.

Acknowledgements

This study was produced with the financial support of the European Union (Kolarctic ENPI CBC Project 02/2011/043/KO303–MineHealth). The authors express their thanks to all members of the MineHealth work group for their contribution and support.

References

- 1.Pilcher JJ, Nadler E, Busch C (2002) Effects of hot and cold temperature exposure on performance: a meta-analytic review. Ergonomics 45, 682–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anttonen H, Pekkarinen A, Niskanen J (2009) Safety at work in cold environments and prevention of cold stress. Ind Health 47, 254–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heus R, Daanen HAM, Havenith G (1995) Physiological criteria for functioning of hands in the cold: a review. Appl Ergon 26, 5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rissanen S, Hassi J, Juopperi K, Rintamäki H (2001) Effects of whole body cooling on sensory perception and manual performance in subjects with Raynaud’s phenomenon. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 128, 749–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rintamäki H, Hassi J, Oksa J, Mäkinen T (1992) Rewarming of feet by lower and upper body exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 65, 427–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fanger PO. (1970) Thermal comfort. Copenhagen: Danish Technical Press. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gavhed DC, Nielsen R, Holmér I (1991) Thermoregulatory and subjective responses of clothed men in the cold during continuous and intermittent exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 63, 29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu Y, Wang F, Wan X, Song G, Shi W, Zhang C (2015) Clothing resultant thermal insulation determined on a movable thermal manikin. Part I: effects of wind and body movement on total insulation. Int J Biometeorol 59, 1475–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen YS, Fan J, Zhang W (2003) Clothing thermal insulation during sweating. Text Res J 73, 152–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Havenith G, Nilsson HO (2004) Correction of clothing insulation for movement and wind effects, a meta-analysis. Eur J Appl Physiol 92, 636–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jussila K. (2016) Clothing physiological properties of cold protective clothing and their effects on human experience. Doctoral thesis. Tampere University of Technology, Publication 1371, 1–89. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-15-3708-0. Accessed August 25, 2017.

- 12.Chen YS, Fan J, Qian X, Zhang W (2004) Effect of garment fit on thermal insulation and evaporative resistance. Text Res J 74, 742–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.EN 342 (2004) Protective clothing. Ensembles for protection against cold. European Committee for Standardization, Brussels.

- 14.Jussila K, Rissanen S, Parkkola K, Anttonen H (2014) Evaluating cold, wind, and moisture protection of different coverings for prehospital maritime transportation—a thermal manikin and human study. Prehosp Disaster Med 29, 580–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.EN ISO 15831 (2004) Clothing. Physiological effects. Measurement of thermal insulation by means of a thermal manikin. International Organisation for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland

- 16.MineHealth (2012) Questionnaire—All questions. Sustainability of miner’s well-being, health, work ability in the Barents region—A common challenge. MineHealth. Working Document No. WP2-D.3.1.

- 17.Burström L, Aminoff A, Björ B, Mänttäri S, Nilsson T, Pettersson H, Rintamäki H, Rödin I, Shilov V, Talykova L, Vaktskjold A, Wahlström J (2017) Musculoskeletal symptoms and exposure to whole-body vibration among open-pit mine workers in the Arctic. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 30, 553–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MineHealth (2015) Final report. Sustainability of miner’s well-being, health, work ability in the Barents region—A common challenge. MineHealth, March 2012—December 2014. Working Document No. W P5-D, 8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.ISO 9920 (2007), Ergonomics of the thermal environment. Estimation of thermal insulation and water vapour resistance of a clothing ensemble. International Organisation for Standardization.

- 20.ISO 11079 (2007) Ergonomics of the thermal environment—Determination and interpretation of cold stress when using required clothing insulation (IREQ) and local cooling effects. International Organisation for Standardization.