Abstract

BACKGROUND:

In September 2011, the government of Ontario implemented payment incentives to encourage the delivery of community-based psychiatric care to patients after discharge from a psychiatric hospital admission and to those with a recent suicide attempt. We evaluated whether these incentives affected supply of psychiatric services and access to care.

METHODS:

We used administrative data to capture monthly observations for all psychiatrists who practised in Ontario between September 2009 and August 2014. We conducted interrupted time-series analyses of psychiatrist-level and patient-level data to evaluate whether the incentives affected the quantity of eligible outpatient services delivered and the likelihood of receiving follow-up care.

RESULTS:

Among 1921 psychiatrists evaluated, implementation of the incentive payments was not associated with increased provision of follow-up visits after discharge from a psychiatric hospital admission (mean change in visits per month per psychiatrist 0.0099, 95% confidence interval [CI] −0.0989 to 0.1206; change in trend 0.0032, 95% CI −0.0035 to 0.0095) or after a suicide attempt (mean change −0.0910, 95% CI −0.1885 to 0.0026; change in trend 0.0102, 95% CI 0.0045 to 0.0159). There was also no change in the probability that patients received follow-up care after discharge (change in level −0.0079, 95% CI −0.0223 to 0.0061; change in trend 0.0007, 95% CI −0.0003 to 0.0016) or after a suicide attempt (change in level 0.0074, 95% CI −0.0094 to 0.0366; change in trend 0.0006, 95% CI −0.0007 to 0.0022).

INTERPRETATION:

Our results suggest that implementation of the incentives did not increase access to follow-up care for patients after discharge from a psychiatric hospital admission or after a suicide attempt, and the incentives had no effect on supply of psychiatric services. Further research to guide design and implementation of more effective incentives is warranted.

Pay for performance has been employed by many jurisdictions to improve the delivery of evidence-based care, to expand access and to improve health outcomes.1 In Canada, some provinces have implemented pay-for-performance incentives, particularly for primary care physicians, 2–6 despite the equivocal and limited nature of the evidence supporting them. In September 2011, the government of Ontario introduced bonus payments to encourage psychiatrists to provide rapid access to patients within 30 days of discharge after a psychiatric hospital admission and for 6 months after a suicide attempt. These are both high-risk periods for adverse events, and there is evidence that access to timely follow-up care may reduce the risk.7 By encouraging the delivery of follow-up care, the objective of these incentives was to help reduce the risk of deterioration, early readmission to hospital and possibly further suicide attempts. Implementation of these incentives followed similar attempts by provincial governments to improve the supply of services to high-risk patients in primary care settings.2,3,5,6 In particular, the government of Ontario has introduced incentives to encourage primary care physicians to roster patients with severe mental illness. In British Columbia, incentives have been implemented to encourage primary care physicians to create mental health care plans in collaboration with patients with a diagnosed mental illness.4

In this study, we investigated whether psychiatrists changed their practice patterns in response to the September 2011 incentives, and whether patients at high risk had better access to psychiatrists. Our research questions were as follows: What is the effect of financial incentives on psychiatrist supply of community-based mental health and addiction care after discharge from hospital or after a suicide attempt? Can financial incentives increase access to community-based psychiatric care for patients after discharge or after a suicide attempt?

Methods

Setting

This longitudinal study was conducted in Ontario, where, in September 2011, the provincial government introduced 3 incentive payments to encourage the delivery of community-based psychiatric care. The first payment incentive (billing code K187) pays psychiatrists a 15% premium on specified service codes for providing outpatient care within 30 days after discharge from a psychiatric hospital admission. The second incentive (billing code K188) pays psychiatrists a 15% premium for specified services delivered during the 180 days after a suicide attempt. The third incentive (billing code K189) pays psychiatrists an annual $200 fee for each patient for whom they provide follow-up within the community in the 4-week period after discharge from a psychiatric hospital admission.

Data sources

We used administrative data collected by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care and shared, via contractual agreement, with the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES). These data included information on physician and practice characteristics, physician claims, patient characteristics, admissions to designated psychiatric hospital beds, emergency department visits and suicide attempts. We also used census data to obtain geographic (e.g., rurality measured using the Rurality Index of Ontario8) and socioeconomic variables. These data sets were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at ICES. Further details on the databases can be found in Appendix 1 (available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.160816/-/DC1).

The study period was September 2009 to August 2014. We captured monthly observations on 3 distinct cohorts over this period. The first cohort consisted of all practising psychiatrists in Ontario, except for those who did not appear both before and after implementation of the incentives. The second and third cohorts captured all patients with discharge from a psychiatric hospital admission and all patients with an emergency department visit for a suicide attempt during the study period, respectively. We excluded patients under 16 years of age (because few cases of severe mental illness are diagnosed before this age), those who were not eligible for public health care insurance, those who were not Ontario residents and those who had missing information on key variables. We treated observations on the same patient within a 30-day period as a single event, and used only the final observation during that period.

Outcomes

For our analysis, we considered 2 outcomes, at the levels of psychiatrists and patients, respectively. At the psychiatrist level, we estimated whether implementation of the incentives resulted in a change in the monthly rates of incentive-eligible services provided after hospital discharge or after a suicide attempt. At the patient level, we estimated whether implementation of the incentives resulted in a change in the likelihood of receiving an incentive-eligible service from a psychiatrist after discharge or after a suicide attempt. An incentive-eligible service was defined as having been provided within 30 days after hospital discharge or within 180 days after a suicide attempt, where billing codes eligible for an incentive payment were applied by the physician.

Covariables

Our main covariables of interest were the level change in the mean monthly number of visits following implementation of the incentives and the change in the slope (rate of change) in the monthly trend following implementation of the incentives.9 We also estimated the slope of the monthly trend before implementation of the incentives.

Statistical analysis

Because the incentives were implemented simultaneously for all psychiatrists in Ontario, and because no suitable comparison group could be generated with provincial data, we used an interrupted time-series design. For both the psychiatrist- and patient-level analyses, we aggregated the outcomes by generating monthly averages, and estimated the outcomes using a linear time-series model (further details are provided in Appendix 1). We used a Portmanteau (Q) test for stationarity of the trend to validate the model.10 For both levels of analysis, we calculated confidence intervals (CIs) using bootstrapped standard errors.

At the psychiatrist level, we stratified psychiatrists into quintiles according to the quantity of incentive-eligible services provided in the pre-incentive period. This allowed us to determine whether the incentives had differential effects on psychiatrists who supplied higher quantities of eligible services in the preincentive period. We also estimated the psychiatrist-level outcomes using individual-level data and an estimator for a count outcome with overdispersion. This allowed us to control for a number of time-varying covariables and unobserved psychiatrist characteristics (Appendix 1).11,12 This alternative specification did produce material changes to our results. Thus, our main findings report the results of the linear model.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the institutional review board at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

Results

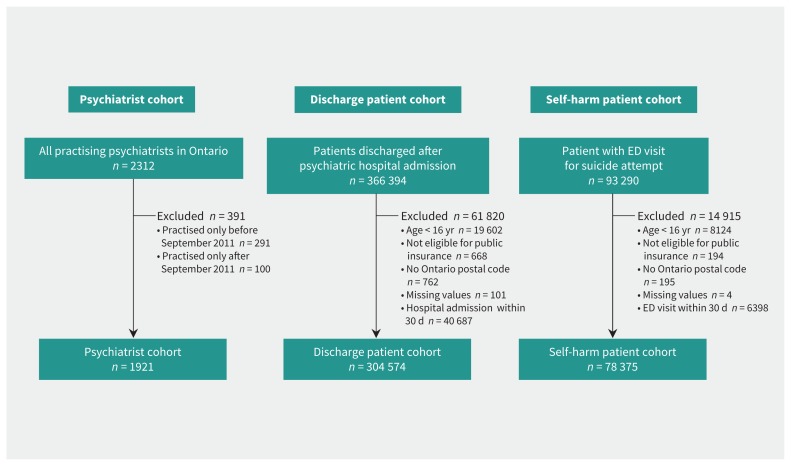

Our sample included 1921 psychiatrists (Figure 1), who were followed over a 60-month period (for a total of 111 924 monthly observations). Compared with the general psychiatrist population, the providers of the highest quantities of eligible visits in the pre-incentive period were less likely to be women (28.7% v. 38.7%), less likely to be trained in Canada (51.7% v. 61.9%) and more likely to be practising in rural areas (Rurality Index of Ontario > 0, 38.5% v. 21.9%) (Table 1).

Figure 1:

Study cohorts. For the psychiatrist cohort, the n values refer to unique psychiatrists. Note: ED = emergency department.

Table 1:

Descriptive statistics for psychiatrist cohort before and after implementation of incentives*

| Covariable | Before incentive† | After incentive‡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Full sample | Lowest quintile§ | Highest quintile§ | Full sample | Lowest quintile§ | Highest quintile§ | |

| No. of observations | 45 024 | 9360 | 9000 | 66 900 | 13 356 | 13 680 |

|

| ||||||

| Sex, female, % | 38.7 (38.2 to 39.1) | 47.1 (46.0 to 48.1) | 28.7 (27.7 to 29.6) | 38.9 (38.5 to 39.3) | 47.8 (47.0 to 48.6) | 28.5 (27.8 to 29.3) |

|

| ||||||

| Age, yr, mean | 54.7 (54.6 to 54.8) | 58.3 (58.0 to 58.5) | 51.7 (51.5 to 51.9) | 56.7 (56.6 to 56.8) | 59.8 (59.6 to 60.0) | 53.8 (53.7 to 54.0) |

|

| ||||||

| Rural practice, % | 21.9 (21.5 to 22.3) | 13.3 (12.6 to 14.0) | 38.5 (37.5 to 39.5) | 22.3 (21.9 to 22.6) | 13.5 (12.9 to 14.1) | 38.9 (38.0 to 39.7) |

|

| ||||||

| Canadian medical graduate, % | 61.9 (61.4 to 62.3) | 70.0 (69.1 to 70.9) | 51.7 (50.7 to 52.7) | 62.1 (61.7 to 62.5) | 71.7 (70.9 to 72.5) | 51.2 (50.4 to 52.1) |

|

| ||||||

| Full-time practice, % | 72.2 (71.8 to 72.6) | 48.6 (47.6 to 49.6) | 94.1 (93.6 to 94.6) | 71.8 (71.4 to 72.1) | 49.0 (48.1 to 49.8) | 94.1 (93.7 to 94.5) |

|

| ||||||

| No. of outpatients seen/yr | 187.7 (185.6 to 189.8) | 53.8 (52.5 to 55.0) | 336.8 (330.9 to 342.6) | 202.0 (200.2 to 203.8) | 57.2 (56.0 to 58.4) | 372.4 (367.5 to 377.3) |

|

| ||||||

| No. of outpatient visits/mo | 94.5 (93.7 to 95.3) | 56.4 (54.9 to 57.8) | 152.4 (150.1 to 154.6) | 90.5 (89.8 to 91.2) | 53.9 (52.8 to 55.0) | 148.1 (145.9 to 150.2) |

|

| ||||||

| No. of patients seen/yr with psychiatric hospital admission in previous year | 33.2 (32.7 to 33.8) | 2.3 (2.1 to 2.4) | 99.7 (97.8 to 101.6) | 36.3 (35.9 to 36.8) | 3.6 (3.4 to 3.9) | 106.0 (104.4 to 107.5) |

All data are shown with 95% confidence intervals.

Pre-incentive period ended in August 2011.

Post-incentive period started in September 2011.

Lowest quintile and highest quintile providers of eligible services in the pre-incentive period.

At the patient level, our sample included 304 574 patients who had been discharged after a psychiatric hospital admission and 78 375 patients with a previous suicide attempt. In the pre-incentive period, patients with at least 1 visit to a psychiatrist in the 30 days after discharge tended to be women (54% v. 48%), tended to be younger (41 yr v. 48 yr), and received greater annual primary care mental health billings (16.6 v. 12.7) and greater annual psychiatrist billings (51.0 v. 13.7) relative to those without a visit (Appendix 2, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.160816/-/DC1). Also in the pre-incentive period, patients with at least 1 visit to a psychiatrist in the 180 days after a suicide attempt tended to be women (62% v. 52%) and received greater annual primary care mental health billings (14.9 v. 5.2) and greater annual psychiatrist billings (27.6 v. 1.9) (Appendix 3, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.160816/-/DC1).

We found that the average quantity of monthly visits per psychiatrist provided after discharge decreased after the introduction of the payment incentives (from 1.50 to 1.43), as did the quantity of monthly visits provided after a suicide attempt (from 1.35 to 1.23) (Table 2).

Table 2:

Effect of the intervention on psychiatrist supply of incentive-eligible visits

| Outcome | Postdischarge visits/mo per psychiatrist* | Post–suicide attempt visits/mo per psychiatrist* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Full sample | Q1–Q3 providers | Q4 and Q5 providers | Full sample | Q1–Q3 providers | Q4 and Q5 providers | |

| Mean eligible visits/mo | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Before introduction of incentives | 1.50 (1.47 to 1.53) | 0.30 (0.29 to 0.31) | 3.33 (3.23 to 3.43) | 1.35 (1.32 to 1.38) | 0.26 (0.25 to 0.27) | 3.03 (2.93 to 3.12) |

|

| ||||||

| After introduction of incentives | 1.43 (1.41 to 1.46) | 0.42 (0.40 to 0.44) | 2.94 (2.85 to 3.03) | 1.23 (1.21 to 1.26) | 0.40 (0.38 to 0.43) | 2.47 (2.40 to 2.54) |

|

| ||||||

| Model estimates† | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Pre-incentive trend‡ | −0.0045 (−0.0102 to 0.0011) | −0.0008 (−0.0028 to 0.0011) | −0.0100 (−0.0230 to 0.0029) | −0.0071 (−0.0117 to −0.0023) | −0.0010 (−0.0035 to 0.0004) | −0.0171 (−0.0267 to −0.0057) |

|

| ||||||

| Change in level after introduction of incentives§ | 0.0099 (−0.0989 to 0.1206) | 0.0862 (0.0506 to 0.1209) | −0.0952 (−0.3211 to 0.1440) | −0.0910 (−0.1885 to 0.0026) | 0.0697 (0.0391 to 0.1244) | −0.3075 (−0.5212 to −0.1210) |

|

| ||||||

| Change in trend after introduction of incentives¶ | 0.0032 (−0.0035 to 0.0095) | 0.0030 (0.0006 to 0.0054) | 0.00008 (−0.0152 to 0.0147) | 0.0102 (0.0045 to 0.0159) | 0.0056 (0.0027 to 0.0086) | 0.0143 (0.0015 to 0.0259) |

|

| ||||||

| Post-incentive trend** | −0.0013 (−0.0050 to 0.0020) | 0.0022 (0.0008 to 0.0035) | −0.0098 (−0.0172 to −0.0032) | 0.0030 (−0.0003 to 0.0062) | 0.0046 (0.0021 to 0.0064) | −0.0029 (−0.0091 to 0.0031) |

Note: Q1 to Q5 represent quintiles, where Q1 = lowest quintile and Q5 = highest quintile for the quantity of incentive-eligible services provided in the pre-incentive period.

All estimates are presented with 95% confidence intervals.

Confidence intervals on model estimates were calculated with bootstrap standard errors (using 1000 replications). All estimates are conditional on other model covariables (not reported).

The monthly change in the mean number of visits before introduction of the incentives.

The level change in the mean monthly number of visits after introduction of the incentives.

The change in the trend for mean monthly number of visits after introduction of the incentives, compared with the monthly trend before introduction of the incentives.

The monthly change in the mean number of visits after introduction of the incentives.

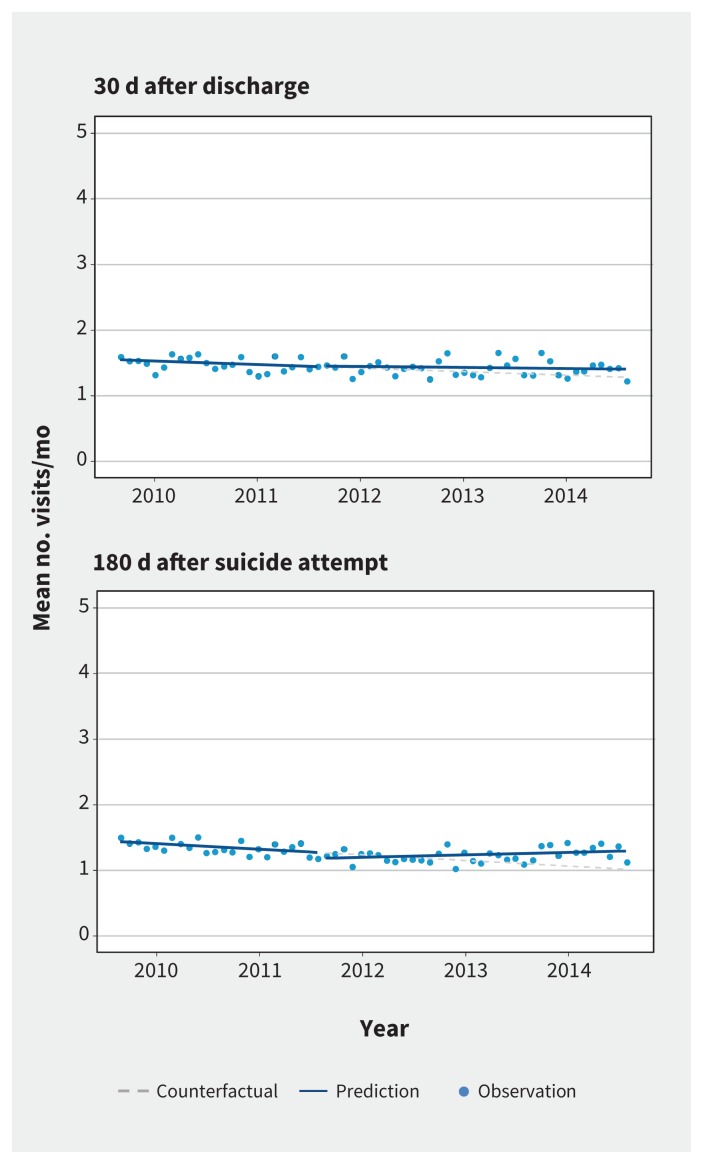

The results of our interrupted time-series analysis (Table 2) suggest that there was no immediate effect of the incentives on the quantity of visits supplied to patients after hospital discharge (mean change in visits per month per psychiatrist 0.0099, 95% CI −0.0989 to 0.1206) or after a suicide attempt (mean change −0.0910, 95% CI −0.1885 to 0.0026). There was also no change in the slope of the monthly trend for visits after hospital discharge (0.0032, 95% CI −0.0035 to 0.0095). There was a small increase in the monthly trend for visits provided after a suicide attempt (0.0102, 95% CI 0.0045 to 0.0159), which translated into a post-incentive monthly trend of 0.003 more visits per month. These findings are presented graphically in Figure 2.

Figure 2:

Mean monthly number of eligible psychiatrist visits: 30 days after discharge from psychiatric hospital admission (top) and 180 days after a suicide attempt (bottom).

We also analyzed these data by quintiles, according to the number of eligible visits in the pre-incentive period (Table 2). For psychiatrists who provided the least number of eligible visits in the pre-incentive period (i.e., first to third quintiles), we observed a statistically significant immediate increase in the monthly quantity of visits provided after discharge (0.0862, 95% CI 0.0506 to 0.1209) and after a suicide attempt (0.0697, 95% CI 0.0391 to 0.1244). However, the magnitude of these effects was small (less than 0.1 visits per month per psychiatrist). There was also a small change in the slope of the monthly trend following implementation of the incentives for postdischarge visits (0.0030, 95% CI 0.0006 to 0.0054) and for visits provided after a suicide attempt (0.0056, 95% CI 0.0027 to 0.0086).

For psychiatrists who provided the most eligible visits in the pre-incentive period (i.e., fourth and fifth quintiles), we did not observe a statistically significant change in the monthly quantity of visits provided after hospital discharge (−0.0952, 95% CI −0.3211 to 0.1440), but did observe a statistically significant immediate decrease in the monthly quantity of visits provided after a suicide attempt (−0.3075, 95% CI −0.5212 to −0.1210). There was also no change in the slope of the monthly trend for postdischarge visits, and a small significant change in trend for visits provided after a suicide attempt (0.0143, 95% CI 0.0015 to 0.0259). However, postdischarge visits displayed a slightly decreasing monthly trend overall after implementation of the incentives.

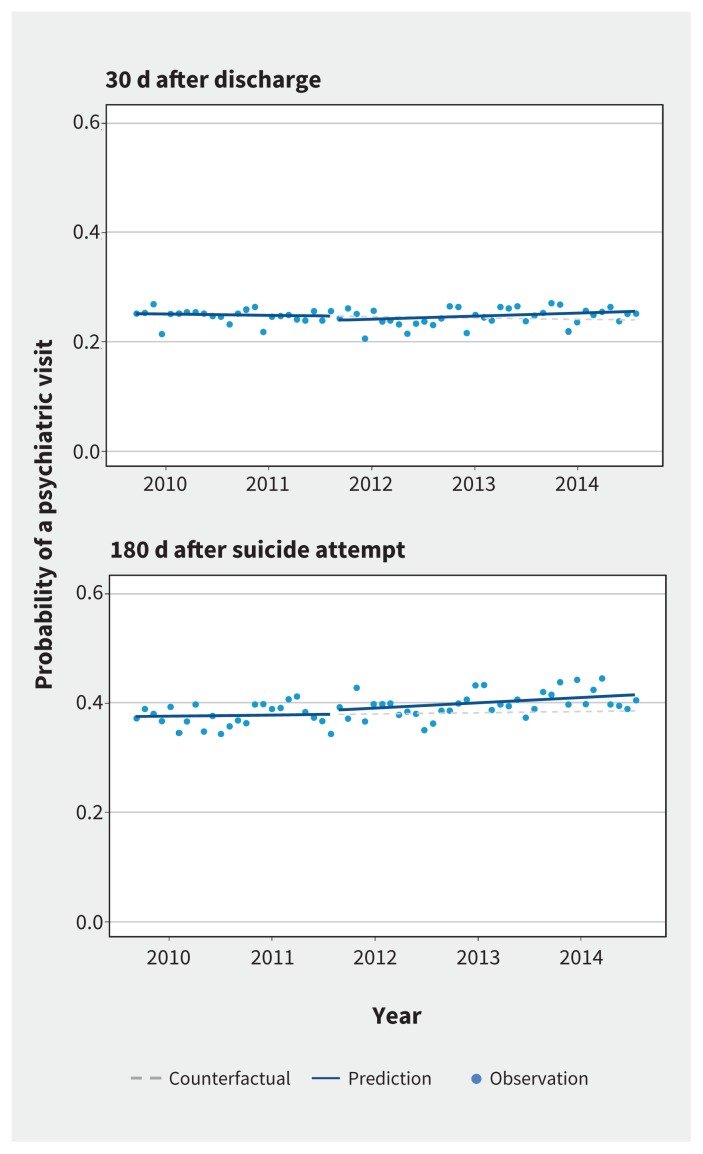

The findings from our patient-level analysis (Table 3) suggest that the likelihood of receiving an eligible visit after hospital discharge or after a suicide attempt remained static over the study period. Implementation of the incentives had no immediate effect on the probability of a patient seeing a psychiatrist 30 days after discharge (change in level −0.0079, 95% CI −0.0223 to 0.0061; change in trend 0.0007, 95% CI −0.0003 to 0.0016) or 180 days after a suicide attempt (change in level 0.0074, 95% CI −0.0094 to 0.0366; change in trend 0.0006, 95% CI −0.0007 to 0.0022). There was also no change in the slope of the monthly trend of the probability of a postdischarge visit (0.0007, 95% CI −0.0003 to 0.0016) or the probability of a visit after a suicide attempt (0.0006, 95% CI −0.0007 to 0.0022). These findings are presented graphically in Figure 3.

Table 3:

Effect of the intervention on the probability of visiting a psychiatrist

| Model estimate | Probability of visiting psychiatrist (95% CI)* | |

|---|---|---|

| 30 d after psychiatric hospitalization discharge | 180 d after suicide attempt | |

| Pre-incentive trend† | −0.0002 (−0.0010 to 0.0006) | 0.0002 (−0.0013 to 0.0012) |

| Change in level after introduction of incentives‡ | −0.0079 (−0.0223 to 0.0061) | 0.0074 (−0.0094 to 0.0366) |

| Change in trend after introduction of incentives§ | 0.0007 (−0.0003 to 0.0016) | 0.0006 (−0.0007 to 0.0022) |

| Post-incentive trend¶ | 0.0005 (0.0000 to 0.0009) | 0.0009 (0.0001 to 0.0015) |

Note: CI = confidence interval.

CIs on model estimates were calculated with bootstrap standard errors (using 1000 replications).

The monthly change in the probability of a visit before introduction of the incentives.

The level change in the probability of a visit after introduction of the incentives.

The change in the trend for probability of a visit after introduction of the incentives, compared with the monthly trend before introduction of the incentives.

The monthly change in the probability of a visit after introduction of the incentives.

Figure 3:

Probability of a psychiatric visit: 30 days after discharge from a psychiatric hospital admission (top) and 180 days after a suicide attempt (bottom).

To further explore the psychiatrist-level results, we calculated the proportion of psychiatrists who billed the payment incentives, and the proportion of eligible services provided where the incentive payment was used (Table 4). The proportion of psychiatrists who billed the various incentive codes ranged from 8.5% for K189 to 23.7% for K187. The proportion of eligible services to which an incentive code was applied ranged from 1.35% (95% CI 1.26% to 1.44%) for K189 to 5.50% (95% CI 5.33% to 5.67%) for K187 for all psychiatrists. However, among psychiatrists who billed at least 1 incentive code, these proportions ranged from 95.77% (95% CI 95.20% to 96.34%) for K188 to 99.96% (95% CI 99.91% to 100.00%) for K189. These results suggest that a small proportion of psychiatrists billed the incentives, and that those who used the incentive codes did so for a majority of their eligible visits.

Table 4:

Number of psychiatrists who billed incentives and proportion of eligible visits with incentive code

| Incentive code | No. (%) of psychiatrists who billed code n = 1921 | Group; % of eligible visits billed (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All psychiatrists | Psychiatrists billing ≥ 1 incentive code | ||

| K187 | 456 (23.7) | 5.50 (5.33 to 5.67) | 97.62 (97.31 to 97.94) |

| K188 | 336 (17.5) | 2.93 (2.80 to 3.06) | 95.77 (95.20 to 96.34) |

| K189 | 163 (8.5) | 1.35 (1.26 to 1.44) | 99.96 (99.91 to 100.00) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, K187 = incentive code for “acute post-discharge community psychiatric care,” K188 = incentive code for “high risk community psychiatric care,” K189 = incentive code for “urgent community psychiatric follow-up.”

Interpretation

The 3 incentives implemented in Ontario did not have a meaningful effect on psychiatrist behaviour or on the likelihood that patients would receive psychiatric care after discharge from hospital or after a suicide attempt. The rates of follow-up care and the quantity of follow-up services provided remained static over the study period.

We propose 2 explanations for these findings. The first concerns the design and implementation of the incentives. Using the average fee for eligible services, the incentive payment per eligible service was about $30, which may not have been large enough to alter psychiatrist behaviour or to encourage psychiatrists to incorporate the incentive codes into their usual billing routines. A similar study of Ontario’s diabetes incentive payment for primary care physicians also showed minimal improvements in care,2 and, like us, that study’s authors suggested that the result may have been due to the size of the incentive payment.2 There is some evidence that the size of the incentive must be large enough to achieve behaviour response.13–19 One study surveyed managers of health management organizations in the United States about how primary care physicians responded to financial incentives, and showed that bonuses of at least 5% of income would be sufficient to achieve behaviour change.15 Other research has identified several factors influencing the impact of pay for performance, including incentive size, duration, group versus individual incentives and case-mix risk-adjustment techniques.1,13,17,18 The literature also suggests that communication and consultation can be key factors in the success of pay-for-performance interventions, in particular, the involvement of providers in the design of performance measures and incentives.13,18 It is possible that many Ontario psychiatrists simply did not know that the incentive payments were available.

The second explanation concerns the context in which the incentives were implemented. Kurdyak and colleagues20 described great variation in the way psychiatric services are delivered in Ontario. Psychiatrists practising in urban areas, such as Toronto, were more likely to see fewer patients, but provided those patients with higher quantities of services. In the current study, we found that psychiatrists practising in urban areas were less likely to provide follow-up care and were less likely to take on newly discharged patients. The effectiveness of financial incentives may be limited for these psychiatrists, particularly if they are satisfied with the level of income they receive from their current practice. There is evidence that once physicians reach a target income, the availability of additional payments will not lead to significant behaviour change.13,21 Unfortunately, we do not have access to information on psychiatrists’ preferences; further exploration of these preferences and views concerning payment could be the topic of future research.

Our results are in line with existing research. Using similar data, previous evaluations of pay for performance for primary care physicians in Canada have yielded mixed results2,6 or shown no effects.3,4 The proportion of physicians billing the incentives was lower in our case than in other similar studies2,3,6 but was similar to the proportion of primary care physicians billing certain of the incentives in the study by Li and colleagues.6

Although pay for performance has been widely implemented, there is equivocal and limited evidence regarding its effectiveness. 19,22–27 A systematic review of the effect of financial incentives for primary care physicians found modest or no effects.23 Lavergne and colleagues4 evaluated pay-for-performance payments for primary care physicians in BC and found that incentives had no effect on visits or continuity of care, but were associated with increased rates of hospital admission. Several studies of primary care pay for performance for cancer screening and diabetes management have been conducted in Ontario,2,3,6 with similarly equivocal results. For instance, Kiran and colleagues3 evaluated incentives for cancer screening for primary care physicians in Ontario and found no effect on cancer screening rates, which were already increasing before implementation of the incentives. Li and colleagues,6 in an evaluation of a series of preventive care pay-for-performance incentives for primary care physicians in Ontario, found that a small proportion of eligible physicians billed these claims (between 2% and 47% in most periods) and that the introduction of the incentives had modest effects on preventive care.

Most work thus far has been on primary care incentives, whereas little work has investigated pay for performance for mental health and addiction services in general or on psychiatrist behaviour specifically. Gutacker and colleagues28 evaluated whether incentives in the Quality for Outcomes Framework in the United Kingdom led to reductions in hospital admission for individuals with severe mental illness. Using data on a sample of 8234 primary care physician practices, they found that the achievement of quality indicators for mental health and addiction care was associated with higher rates of psychiatric admission. In the US, Unützer and colleagues29 evaluated a pay-for-performance incentive that was part of a larger quality improvement intervention for a state-funded community health plan for low-income adults with physical or mental health conditions (n = 1673 patients before and n = 6304 patients after implementation of the incentive). These authors found that the pay-for-performance payment was associated with improvements in timely follow-up and in time to depression improvement. Two US studies30,31 found that incentives for psychiatrists had positive effects on quality measures and access. Using a cluster randomized trial design (including 105 therapists and 986 patients), the authors found that a pay-for-performance intervention to improve treatment for adolescents with substance use disorders had a positive effect on the use of evidence-based treatment, but no effect on patient outcomes.31

Limitations

This study had some limitations. First, we did not have a comparison group and relied on time-series variation to assess the effect of the payment incentives. It is possible that in the absence of these incentive payments, there would have been a discontinuity in the trends; however, we believe this is unlikely, given the stability of the observed trends. Second, our study suffered from censoring. Psychiatrists drop out of practice for unknown reasons (e.g., parental leave, leaving the province), and we were unable to control for this factor with the available data.

Conclusion

We found that incentives to encourage community-based psychiatric follow-up care were not associated with improvements in access to care or changes in physician behaviour. Although we focused on the situation in Ontario, our findings will be important for policy-makers in all high-income countries where the use of payment incentives to improve health care delivery is an important concern. Our results do not necessarily suggest that financial incentives should be abandoned as a tool to improve the delivery of health care services, but they do indicate that careful thought should be given to the design of such incentives and the context in which they are implemented. For instance, further research using a mixed-methods design could explore why psychiatrists were not responsive to these particular incentives, and whether specific features of the Ontario context were contributing factors. As it stands, the provincial investment in these incentive payments has not produced any discernible value, and psychiatrists are not responding.

See related articles at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.170092 and www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.171126

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: David Rudoler oversaw the data collection, conducted the statistical analysis, and drafted and revised the paper. Claire de Oliveira oversaw the data collection, provided advice on statistical analysis, and contributed to the final draft and revision of the manuscript. Joyce Cheng collected and cleaned the data for analysis and contributed to the initial draft and revision of the manuscript. Paul Kurdyak provided project oversight, advice on the data collection process and the statistical analysis, and guidance on interpretation of the findings; he also contributed to the initial draft and revision of the manuscript. All of the authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: No direct funding was received for this project. David Rudoler’s postdoctoral work is supported by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences and the University of Toronto.

Disclaimer: This study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). In addition, parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information. The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred.

References

- 1.Cashin C, Chi YL, Smith PC, et al., editors. Paying for performance in health care: implications for health system performance and accountability. Berkshire (UK): Open University Press, McGraw Hill Education; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kiran T, Victor JC, Kopp A, et al. The relationship between financial incentives and quality of diabetes care in Ontario, Canada. Diabetes Care 2012; 35:1038–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiran T, Wilton AS, Moineddin R, et al. Effect of payment incentives on cancer screening in Ontario primary care. Ann Fam Med 2014;12:317–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lavergne MR, Law MR, Peterson S, et al. A population-based analysis of incentive payments to primary care physicians for the care of patients with complex disease. CMAJ 2016;188:E375–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kantarevic J, Kralj B. Link between pay for performance incentives and physician payment mechanisms: evidence from the diabetes management incentive in Ontario. Health Econ 2013;22:1417–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li J, Hurley J, DeCicca P, et al. Physician response to pay-for-performance: evidence from a natural experiment. Health Econ 2014;23:962–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vigod SN, Kurdyak PA, Dennis CL, et al. Transitional interventions to reduce early psychiatric readmissions in adults: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry 2013;202:187–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kralj B. Measuring “rurality” for purposes of health-care planning: an empirical measure for Ontario. Ont Med Rev 2000;67:33–52. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, et al. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther 2002; 27:299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ljung GM, Box GEP. On a measure of lack of fit in time series models. Biometrika 1978;65:297–303. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allison PD. Quantitative applications in the social sciences. Vol. 160: Fixed effects regression models. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cameron AC, Trivedi PK. Microeconometrics: methods and applications. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eijkenaar F. Key issues in the design of pay for performance programs. Eur J Health Econ 2013;14:117–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mullen KJ, Frank RG, Rosenthal MB. Can you get what you pay for? Pay-forperformance and the quality of healthcare providers. Rand J Econ 2010; 41:64–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hillman AL, Pauly MV, Kerman K, et al. HMO managers’ views on financial incentives and quality. Health Aff (Millwood) 1991;10:207–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hillman AL, Ripley K, Goldfarb N, et al. Physician financial incentives and feedback: failure to increase cancer screening in Medicaid managed care. Am J Public Health 1998;88:1699–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maynard A. The powers and pitfalls of payment for performance. Health Econ 2012;21:3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bremer RW, Scholle SH, Keyser D, et al. Pay for performance in behavioral health. Psychiatr Serv 2008;59:1419–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armour BS, Pitts MM, Maclean R, et al. The effect of explicit financial incentives on physician behavior. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:1261–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurdyak P, Stukel TA, Goldbloom D, et al. Universal coverage without universal access: a study of psychiatrist supply and practice patterns in Ontario. Open Med 2014;8:e87–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rizzo JA, Zeckhauser RJ. Reference incomes, loss aversion, and physician behavior. Rev Econ Stat 2003;85:909–22. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Town R, Kane R, Johnson P, et al. Economic incentives and physicians’ delivery of preventive care: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2005;28:234–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scott A, Sivey P, Ait Ouakrim D, et al. The effect of financial incentives on the quality of health care provided by primary care physicians. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(9):CD008451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Herck P, De Smedt D, Annemans L, et al. Systematic review: effects, design choices, and context of pay-for-performance in health care. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christianson JB, Leatherman S, Sutherland K. Lessons from evaluations of purchaser pay-for-performance programs: a review of the evidence. Med Care Res Rev 2008;65(6 Suppl):5S–35S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conrad DA, Christianson JB. Penetrating the “black box”: financial incentives for enhancing the quality of physician services. Med Care Res Rev 2004;61(3 Suppl):37S–68S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gillam SJ, Siriwardena AN, Steel N. Pay-for-performance in the United Kingdom: impact of the quality and outcomes framework: a systematic review. Ann Fam Med 2012;10:461–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gutacker N, Mason AR, Kendrick T, et al. Does the quality and outcomes framework reduce psychiatric admissions in people with serious mental illness? A regression analysis. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Unützer J, Chan YF, Hafer E, et al. Quality improvement with pay-for-performance incentives in integrated behavioral health care. Am J Public Health 2012; 102:e41–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garner BR, Godley SH, Bair CML. The impact of pay-for-performance on therapists’ intentions to deliver high-quality treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat 2011;41:97–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garner BR, Godley SH, Dennis ML, et al. Using pay for performance to improve treatment implementation for adolescent substance use disorders: results from a cluster randomized trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2012;166:938–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]