Abstract

The aetiology of intervertebral disc (IVD) degeneration accompanied by low back pain (LBP) is largely unknown, and there are no effective fundamental therapies. Symptomatic IVD is known to be associated with nerve root compression. However, even in the absence of nerve compression, LBP occurs in patients with IVD degeneration. We hypothesize that this phenomenon is associated with a concentration of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1β and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), which can lead to altered histologic features and cellular phenotypes observed during IVD degeneration. This study investigated the effects of the concentration of IL-1β and macrophage derived soluble factor including IL-1β and TNF-α on the painful response of human annulus fibrosus (AF) cells using a newly developed spine-on-a-chip. Human AF cells were treated with a range of concentrations of IL-1β and macrophage soluble factors. Our results show that increasing the concentration of inflammatory initiator caused modulated expression of pain-related factors, angiogenesis molecules, and catabolic enzymes. Furthermore, accumulated macrophage derived soluble factors resulted in morphological changes in human AF cells and kinetic alterations such as velocity, dendritic length, cell area, and growth rate, similar to that reported within degenerative IVD. Thus, a better understanding of the relationships between molecular and kinetic alterations can provide fundamental information regarding the pathology of IVD degenerative progression.

INTRODUCTION

Degeneration of the intervertebral disc (IVD) is a significant cause of low back pain (LBP) and is a large socio-economic burden. IVD degeneration is also one of the highly prevalent conditions in spinal disease. Approximately 84% of individuals suffer from LBP in their lifetimes.1,2 Nevertheless, the aetiology of IVD degeneration accompanied by LBP is largely unknown, and there are no effective fundamental therapies, but a significant proportion of IVD degeneration is known to be associated with inflammatory response.

The IVD is composed of two types of tissues: the inner nucleus pulposus (NP) and outer annulus fibrosus (AF). The vascular structure for nutrient supply and the free nerve ending originating from the dorsal root ganglion are located in the outer third of the AF region.3,4

In a healthy state, synthesis and breakdown of extracellular matrix (ECM) are in equilibrium. However, during IVD degeneration, there is an imbalance between catabolic and anabolic responses, resulting in decreased levels of collagen and proteoglycan.5,6 This imbalanced molecular cascade leads to many histologic features of degenerative IVD tissue including changes in the disc height, water content, and disc homogeneity.7 On the basis of these features, degenerative IVD tissues are classified into five grades (Grade I–V) by MRI T2 spin-echo weighted images.8,9

In general, in the final stage of IVD degeneration (Grade V), MRI images show the extrusion of the NP passing through the fissured AF structure, resulting in the generation of LBP due to nerve root compression. However, even in the absence of nerve compression in MRI images, LBP occurs in patients with IVD degeneration.10 These observations have led to re-consideration of the pathogenesis of LBP and have focused on the relationship between inflammatory cytokines and IVD degeneration, which is considered a major cause of LBP. In addition, there is also a population which has severe disc degeneration with no pain. This is an important piece to the puzzle of IVD degeneration and LBP.11–14 Nevertheless, the aetiology of IVD degeneration with LBP is not completely understood. For this reason, current molecular-based treatment methods, including anti-cytokine and anti-growth factor therapy, have limited effectiveness in the treatment of IVD-related LBP degeneration and still depend on the clinically classified IVD grade using MRI imaging. Thus, a greater understanding of the IVD pathology is essential for optimizing treatment strategies and developing anti-cytokine/growth factor drugs.

As degeneration proceeds, there is an elevated level of pro-inflammatory cytokines including interleukin (IL)-1β and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) originating from activated macrophages, which drive the catabolic cascades within degenerative IVD tissues.15–17 These pro-inflammatory cytokines are strongly linked to the expression of pain-related factors, angiogenesis molecules including IL-6 and IL-8, and extracellular matrix-modifying enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which are associated with matrix remodelling and degenerative IVD conditions.18–21 These molecules are known to be associated with discogenic pain, which occurs in the early stages of IVD degeneration and in the absence of nerve compression.

Generally, in the early stages of IVD degeneration (from non- to mildly degenerate IVD), levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and TNF-α, and mediators have relatively low expression in the disc tissue. In more advanced degenerative conditions (from moderately to severely degenerate), accumulated or over-expressed pro-inflammatory cytokines secreted by immune cells can lead to cell death or phenotypic and genotypic changes in the IVD cells.22–25 Similarly, up-regulated expression of TNF-α and IL-1β with increasing age/degeneration has been investigated, as well as higher levels in symptomatic versus asymptomatic IVD degeneration. It was also reported that invasion of macrophages and monocytes was observed in symptomatic IVD degeneration. Additionally, herniated IVD grades show more IL-8 and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) than scoliotic IVD.22,26,27 In the final stage, matrix alarmins and cytokines might modulate the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) pain channel activity or irritate nerve endings located in the AF region, resulting in pain.

With regard to the morphological characteristics in vivo, following accumulation of these cytokines on chronic injury, fibroblasts become activated and transdifferentiated into myofibroblast-like cells, which are characterized by expressing α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), increased migration velocity, and a capacity to secrete the matrix modifying enzymes for tissue repair.28,29

However, whether concentration changes in IL-1β and soluble factors derived from macrophages, which can be expected to increase with the severity of IVD degeneration, can directly affect the expression of pain-related factors (IL-6 and -8), catabolic enzymes (MMP-1 and MMP-3), and cellular kinetic modulation, which is responsible for disc pain, still remains to be elucidated.

Our aim was to confirm the molecular regulation of the catabolic and inflammatory response of human AF cells in specific concentrations of IL-1β and macrophage-mediated IVD degeneration and to validate the availability of a newly developed microfluidic-based gradient spine-on-a-chip. Furthermore, we measured the kinetic parameters (cell area, velocity, growth rate, dendritic length, and morphological changes) in human AF cells treated with soluble factors derived from macrophage-like THP-1 cells for mimicking the immune response during the progression of IVD degeneration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human AF cell isolation and culture

Human AF cells were isolated from the disc tissues removed during elective surgical procedures on 5 patients (1 woman and 4 men). This study was conducted with the approval of the institutional review board of Korea University Guro Hospital (KUGH12202-001), and we obtained informed consent from the patients for the use of their IVD tissues. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The tissue specimens were placed in sterile Ham's F-12 medium supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S; Gibco-BRL) and 5% foetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco-BRL). The tissues were washed three times with Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS; Gibco-BRL) containing 1% P/S to remove blood and other contaminants. After washing the tissues, the definitive AF regions were dissected and digested for 60 min in F-12 medium containing 1% P/S, 5% FBS, and 0.2% pronase (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA), followed by a day of incubation in medium containing 0.025% collagenase. A sterile nylon mesh filter (pore size 70 μm) was used to isolate suspended cells from the tissue debris. The suspended cells were centrifuged at 676 g for 5 min and resuspended in F-12 medium containing 10% FBS and 1% P/S. The human AF cells were cultured in 75 cm2 cell culture flasks (VWR Scientific Products, Bridgeport, NJ, USA) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

IL-1β stimulation of human AF cells

Human AF cells were cultured in 6-well culture plates in F-12 medium supplemented with 1% P/S and 10% FBS. After the cells were grown to 90% confluence, the culture medium was changed to Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium: Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12; Gibco-BRL) medium containing 1% P/S and 1% FBS in the presence or the absence of recombinant human IL-1β (R&D Systems) for a time- (1 ng/ml treatment for 12, 24, 48, and 72 h) and dose- (1.0, 0.75, 0.5, and 0.25 ng/ml and control for 72 h) dependent experiment. The conditioned medium was collected/stored at −80 °C for enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) analysis and other experiments.

Activation of macrophage-like THP-1 cells and macrophage-derived soluble factor collection

The human leukaemia monocyte cell line THP-1 (ATCC TIB202; ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) has been widely used to investigate immune responses in the macrophage-like state. The monocyte THP-1 cells can be differentiated with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; Sigma) treatment into macrophage-like cells, which can secrete several pro-inflammatory cytokines during IVD degeneration. The monocyte THP-1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (ATCC) containing 1% FBS, 1% P/S, 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (2 ME; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA), and 160 nM PMA. After treatment for 72 h, the differentiated macrophage-like THP-1 cells were washed three times using phosphate buffered saline (PBS; Gibco-BRL). The cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 containing 1% FBS and 1% P/S for an additional 48 h, and then the conditioned medium was collected and stored at −80 °C for the macrophage-derived soluble factor stimulation experiment on human AF cells.

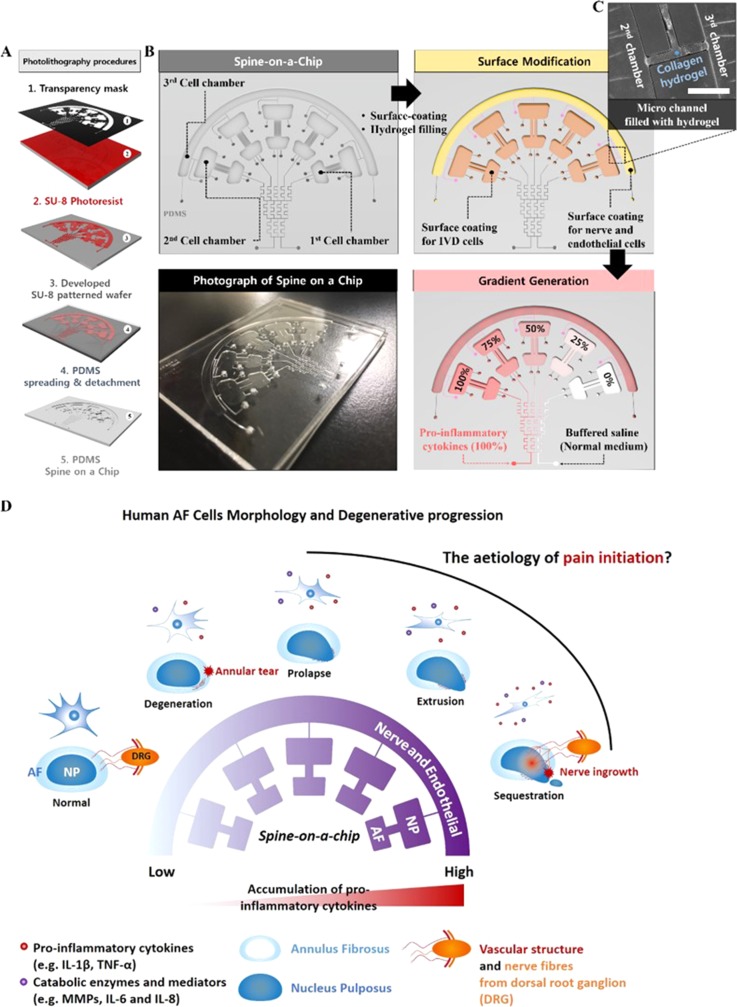

Fabrication of the microfluidic-based gradient co-culture devices and experimental design

We designed an IVD co-culturing microfluidic gradient platform composed of three distinct chambers connected with a micro-patterned gradient channel using standard photolithographic techniques. Figure 1 depicts a schematic diagram of the newly developed spine-on-a-chip and experimental design. The microfluidic device mould was fabricated on a silicon wafer using the standard photolithography procedure [Fig. 1(a)]. The chambers enabled three types of cells (IVD, neuronal, and vascular cells) to be cultured. The 1st and 2nd chambers were directly connected through a microchannel. The 2nd and 3rd chambers were connected through arrays of thin hydrogel channels for studying the paracrine signalling between 2nd and 3rd chamber cells without direct contact. Micropatterned gradient channels were connected to the 1st chamber for pro-inflammatory gradient stimulation [Figs. 1(b)–1(d)]. The diffusion and gradient profiles were simulated using COMSOL Multiphysics computational software (COMSOL Inc., Burlington, MA, USA). After applying a chemical fluorescent dye, intensity was measured using conventional fluorescent microscopy (supplementary material, Figs. S1–S3 and Videos S1–S4).

FIG. 1.

Schematic and experimental design of the microfluidic gradient assay. (a) Schematic diagram of the photolithography procedure. (b) Schematic of the experimental step on the spine chip. (Top-left) schematic of a spine-on-a-chip for studying IVD degeneration. (Top-right) Surface coating and incorporating hydrogel in the microchannel and the chamber. (Bottom-right) Gradient generation procedure in the cell culture chamber using the micromixing patterned channel. (Bottom-left) Photograph of the microfluidic-based gradient spine on a chip. (c) Magnified image of the hydrogel channel. Scale bar = 400 μm. (d) Schematic diagram of expected degenerative progression and human AF cell morphology suggested by this study.

First, the 1st and 2nd cell culture chambers were coated with fibronectin (100 μg/ml) to facilitate IVD cell adhesion; the hydrogel mixture (type 1 collagen, 2.0 mg/ml) was filled into the hydrogel region, which can generate 3D capillary morphogenesis of a vascular structure, and it can also separate the region between the 2nd and 3rd chambers (supplementary material, Fig. S2). The 3rd chamber was coated with a poly-D-lysine (1 mg/ml) for neuronal cell culture. Then, all the chambers and channels were washed more than three times with sterile deionized water. Second, primary AF cells isolated from patients were plated into the 1st chamber at an approximate density of 1.0 × 105 viable cells (in 10 μl plating medium) per chamber. The microfluidic devices were set at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. After 1 h (most AF cells in the 1st chamber adhered to the Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) surface during this period), all the other chambers and channels were filled with DMEM/F12 cell culture medium. Finally, soluble factors and normal culture medium were injected into 5 divided chambers through two side inlets of the gradient-generating microchannel (flow velocity was 4 ml/h) at 37 °C, in which bubble traps for protecting the damage of cells and providing stability of flow were included. After incubation for the designated periods, human AF cells were washed, fixed, and immunostained with F-actin antibody (Santa Cruz) for observing the morphological changes. Kinetic analysis was also performed on dose-gradient-stimulated human AF cells using ZEN 2012 fluorescence analysis software (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, GER) and a Live cell imaging system (EVOS FL auto cell imaging system, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA).

Kinetic analysis

The human AF cells were cultured in 24-well culture plates in DMEM/F12 medium containing soluble factors derived from macrophage-like THP-1 cells for 72 h. During the cell culture period, the time lapse images were acquired using a live cell imaging system. Then, the cell kinetic parameters (velocity, cell area/growth, and dendritic length) were measured using Image J software (version 1.4).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Concentrations of matrix metalloproteinase-1 and -3 (MMP-1 and MMP-3); interleukin-6, -8, and -1beta (IL-6, IL-8, and IL-1β); and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α); and a tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 and -2 (TIMP-1 and TIMP-2) in the supernatant were measured using commercially available ELISA kits (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer's instruction.

Immunofluorescence staining of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells' (NF-κB) p50 protein and alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA)

Human AF cells were plated on a glass-bottom confocal dish and exposed to IL-1β (1 ng/ml) for 48 h. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. Then, the cells were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Millipore) for 1 h at room temperature and incubated overnight at 4 °C with monoclonal NF-κB p50 antibody and α-SMA antibody (Santa Cruz). The cells were then incubated with anti-rabbit Alexa secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) in blocking buffer. Finally, the cells were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Invitrogen). The samples were examined under the EVOS FL auto cell imaging system (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA).

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

Human AF cells were lysed with Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen), RNA was extracted, and complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The quantity and quality of the RNA were determined using a Nanodrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). qRT-PCR was performed for IL-6, IL-8, MMP-1, and MMP-3 using the SYBR Green PCR Master mix method (Applied Biosystems). Messenger RNA (mRNA) expression was analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method, in which values were expressed as the mean fold change normalized to that of the housekeeping gene GAPDH. Naive AF cells were used as controls for AF cells exposed to macrophage-conditioned medium (MCM) in a dose-dependent manner.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard errors for 4 or 5 individual experiments using independent cell cultures. Each of the experimental group had five samples, and an identical experimental procedure was applied four to five times. Hence, we used more than 100 samples. The statistical significance of differences between control and experimental data was analysed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by a post hoc test (Scheffe's method). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 21.3, IBM SPSS Statistics Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The inflammatory response through up-regulation of inflammatory mediators and ECM-modifying enzymes on IL-1β-stimulated-human AF cells

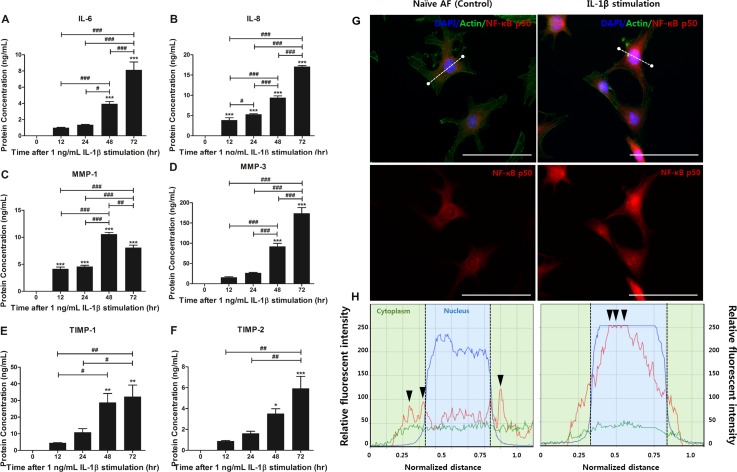

IVD degeneration is characterized by the increase in the production of inflammatory mediators and ECM-modifying enzymes such as IL-6, IL-8, MMP-1, MMP-3, TIMP-1, and TIMP-2 secreted by AF cells. IL-1β-mediated-inflammation is thought to be strongly linked to the pathogenesis of IVD degeneration through nucleus translocation of NF-κB p50 subunit protein. NF-κB is an inducible transcriptional activator that controls the expression of a number of inflammatory mediators and catabolic enzymes.

Therefore, to confirm the effects of IL-1β stimulation on human AF cells, we quantified the production of IL-6, IL-8, MMP-1, MMP-3, TIMP-1, and TIMP-2 secreted by 1 ng/ml IL-1β-stimulated-AF cells in a time-dependent manner (12, 24, 48, and 72 h). Human AF cells not exposed to IL-1β (naïve AF cells) showed scant amounts of IL-6, IL-8, MMP-1, MMP-3, TIMP-1, and TIMP-2. However, the human AF cells in the presence of 1 ng/ml IL-1β showed a dramatic increase in the IL-6, IL-8, MMP-1, MMP-3, TIMP-1, and TIMP-2 production up to 72 h compared to naïve AF cells. The production of IL-6, -8, MMP-3, TIMP-1, and TIMP-2 showed the highest increase after 72 h of IL-1β stimulation except for MMP-1 [Figs. 2(a)–2(f)]. Together, these results demonstrate that an inflammatory response can be induced in human AF cells in response to IL-1β stimulation in a time-dependent manner, and we speculated that 72 h of IL-1β stimulation is a sufficient condition for establishing IVD degeneration in an in vitro model.

FIG. 2.

Production of inflammatory cytokines and ECM-modifying enzymes of human AF cells via NF-κB p50 transcription factor translocation in a time-dependent manner. (a) Production of IL-6 and (b) IL-8 secreted by IL-1β-stimulated-human AF cells was quantified using ELISA. (c) Production of MMP-1, (d) MMP-3, (e) TIMP-1, and (f) TIMP-2. (g) The expression of NF-κB p50 protein was visualized by immunofluorescence staining with an antibody to p50 and (h) measured via fluorescence intensity [white line in (g)] after 1 ng/ml IL-1β stimulation for 72 h. The data showed that p50 protein was translocated into the nucleus [black arrow head in (h)]. The highest intensity of red fluorescence is marked as the black arrow. The translocation of p50 protein demonstrated that the inflammatory response in human AF cells can be sufficiently induced by 1 ng/ml IL-1β stimulation for 72 h. Images were acquired by confocal laser scanning microscopy. ***p < 0.001 vs. naïve AF cells, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p <0.001. Scale bar = 100 μm.

We then used NF-κB p50 subunit antibodies to identify which NF-κB-mediated inflammation markers correlated with the effects of IL-1β stimulation in human AF cells. In general, this subunit is mainly expressed in the cell cytoplasm or has low expression in the whole body. However, in degenerative conditions, the p50 transcription factor is translocated from the cell cytoplasm into the nucleus. Actually, the immunocytochemistry result of our study demonstrated that the p50 subunit was translocated into the nucleus in 1 ng/ml IL-1β-stimulated-human AF cells after 72 h. However, naïve AF cells showed extremely low expression of the factor in the cytoplasm and nucleus compared to the stimulation group [Figs. 2(e) and 2(f)]. On the basis of these results, we postulated that IL-1β stimulation can induce the inflammatory reaction in human AF cells. Together, we performed all the IL-1β stimulation experiments in this study for 72 h.

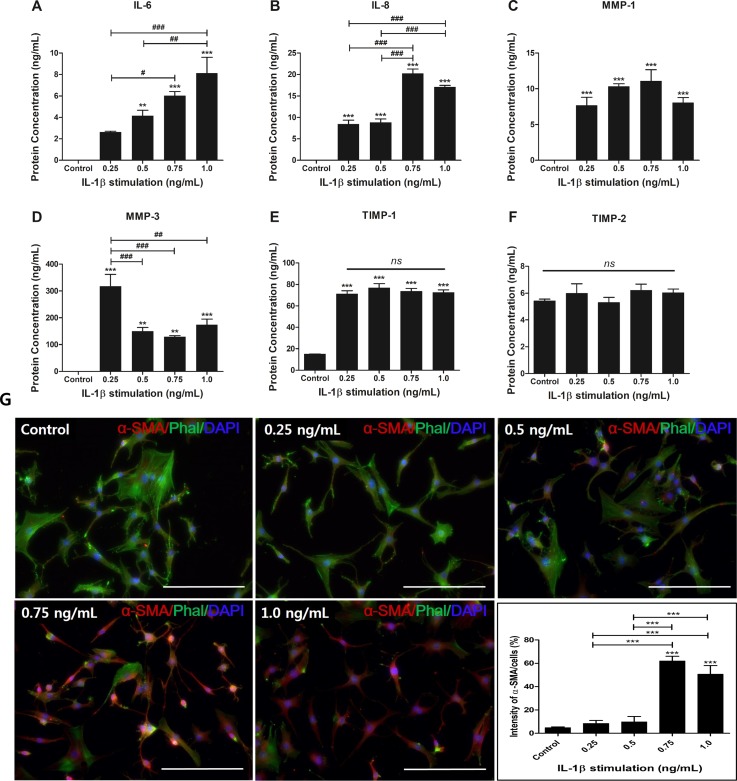

The modulation of inflammatory mediators and ECM-modifying enzyme production of human AF cells through dose-gradient IL-1β stimulation

In general, the severity of IVD degeneration can be classified (Grade I–V) by MRI T2 spin-echo weighted images. The images reflect histological morphological changes caused by degeneration. Therefore, we speculated that the modulated molecular expression is required prior to beginning these histologic changes. We hypothesized that a dose-gradient of IL-1β stimulation reflects the different IVD degeneration grade by modulating the inflammatory mediators and ECM-modifying enzyme production in human AF cells.

To investigate the expression of the inflammatory mediators and catabolic enzymes in human AF cells in a dose-dependent manner, the production of IL-6, IL-8, MMP-1, MMP-3, TIMP-1, and TIMP-2 was quantified by ELISA. Additionally, the IL-1β-induced α-SMA protein level, which is known to mark the differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts in inflammatory and wound conditions, was confirmed by immunofluorescence staining.

Human AF cells were stimulated with IL-1β at different concentrations. IL-6 production in all groups except for the 0.25 ng/ml treatment group significantly increased compared to the naïve AF cells. The human AF cells exposed to 1 ng/ml IL-1β showed the highest secretion of IL-6 production. IL-6 production tended to slightly increase in a dose-dependent manner [Fig. 3(a)]. The results for IL-8 production were more complex. All the treatment groups showed increased production of IL-8 compared to naïve AF cells. However, in the 0.5 ng/ml group, there was no significant change compared to the 0.25 ng/ml group. The human AF cells stimulated with 0.75 ng/ml and 1.0 ng/ml IL-1β showed a significant increase compared to those stimulated with 0.25 and 0.5 ng/ml IL-1β [Fig. 3(b)].

FIG. 3.

Production of the inflammatory mediators and ECM-modifying enzymes and expression of α-SMA protein in dose-dependent IL-1β-stimulated-human AF cells. (a) Production of IL-6, (b) IL-8, (c) MMP-1, (d) MMP-3, (e) TIMP-1, and (f) TIMP-2. (g) The expression of α-SMA protein was visualized by immunofluorescence staining with an antibody to α-SMA. Images were acquired by confocal laser scanning microscopy. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. naïve AF cells. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p <0.001. Scale bar = 200 μm.

In regard to ECM-modifying enzyme production, all the IL-1β-treated groups showed a significant increase compared to naïve AF cells. MMP-1 production showed a slight increase up to 0.75 ng/ml IL-1β treatment [Fig. 3(c)]. In regard to MMP-3 production, interestingly, the lowest dose of IL-1β stimulation in this study resulted in the highest production of MMP-3 [Fig. 3(d)]. TIMP-1 production, as an endogenous inhibitor of MMP-3, was significantly increased in all IL-1β treatment groups, but there was no significant difference in each group [Fig. 3(e)]. In TIMP-2 production, as an endogenous inhibitor of MMP-1 interestingly, it was not significantly influenced by exposure to IL-1β stimulation [Fig. 3(f)]. In this pattern, we speculated that MMP-3 with expression of TIMP-1 plays a central role in matrix degradation in the early stages of inflammatory response when pro-inflammatory cytokine expression is relatively low. Additionally, stably expressed MMP-1 regulates matrix degradation regardless of pro-inflammatory cytokine concentration. These results demonstrated that inflammatory mediators and ECM-modifying enzymes can be modulated by differential doses of IL-1β in human AF cells.

We then examined a specific antibody against α-SMA, which labels myofibroblast-like differentiation of human AF cells and has a high capacity for secretion of ECM-modifying enzymes and inflammatory protein. It plays an important role in ECM remodelling in pathologic condition development. Human AF cells stimulated with 0.75 and 1.0 ng/ml IL-1β showed dramatically increased intensity similar to IL-6 and -8 [Fig. 3(g)].

On the basis of these results, we postulated that dose-gradient IL-1β stimulation can modulate the inflammatory mediators through differentiation into myofibroblasts in human AF cells.

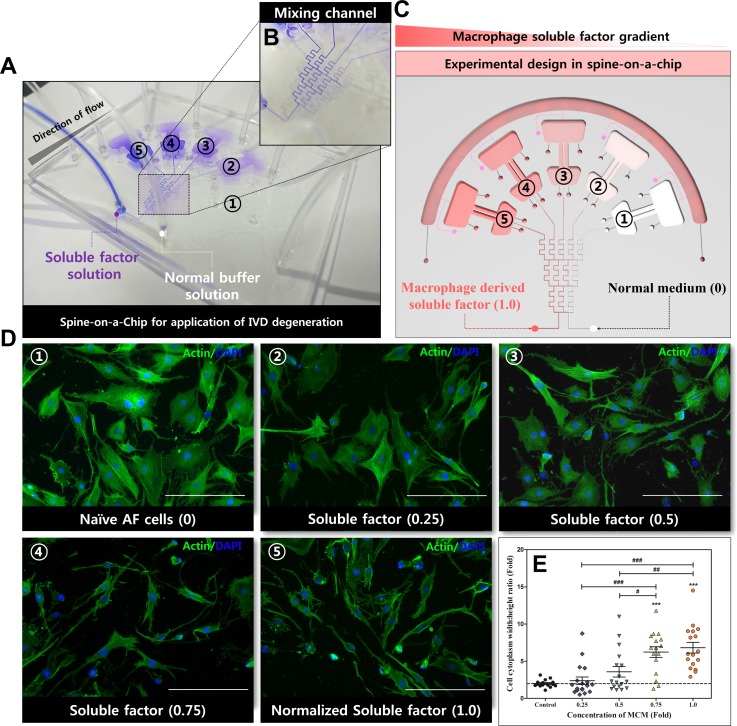

Concentration of soluble factors derived from macrophage-like-THP-1 cells affects the morphological alteration of human AF cells in spine-on-a-chip

During the development of intervertebral disc degeneration, interactions between macrophages and AF cells play an important role in the pathogenesis of inflammation-mediated degeneration. The monocyte, which is located in the vascular structure, infiltrates into human AF tissues in the early stages of tissue degeneration. The monocytes are differentiated into activated macrophage cells that have the capability of secreting a variety of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α and are responsible for the severity of IVD degeneration.

We hypothesized that the soluble factors secreted by activated macrophage-like THP-1 cells induce the inflammatory response in human AF cells, a similar response to that reported within degenerative IVD. Furthermore, these molecules may trigger a range of pathogenic responses in human AF cells that promote morphologic and kinetic alterations. Thus, to mimic IVD degeneration, we evaluated the morphologic changes in human AF cells treated with soluble factors derived from macrophage-like THP-1 cells using kinetic analysis (velocity, cell area, dendritic length, and cell area) in a spine-on-a-chip.

In order to characterize the concentration gradient profiles in the mixing channel of the spine-on-a-chip, the gradient profile was simulated using conventional simulation software and the normalized mass fraction of the soluble factor concentration was measured using a confocal laser-scanning microscope (data not shown). By using blue dye, we visualized the gradient formation, as the streams of dye flow in the micromixing channel [Figs. 4(a) and 4(b)]. We quantitatively defined the gradient profile in the human AF cell culture chamber; an undiluted soluble factor is defined as a normalized concentration of 1.0 (severely degenerated IVD) [Fig. 4(c)].

FIG. 4.

The morphologic modulation effects of the gradient concentration of soluble factors derived from macrophages on human AF cells in spine-on-a-chip. (a) Using blue dye to make the gradient formation visualization. (b) The magnified image of the gradient mixing microchannel. (c) Experimental design for the application of macrophage soluble factor on human AF cells in spine-on-a-chip. (d) Fluorescence staining for F-actin (green) on human AF cells in a soluble factor gradient-dependent manner. Soluble factor from macrophage-like THP-1 cells was added to the left inlet of the mixing channel, and normal DMEM/F12 (1% P/S and 1% FBS) was added to the right inlet. Morphological changes were detected in human AF cells in microfluidic devices. (e) Cell cytoplasm width: height-length ratios were measured from fluorescence images using confocal image processing software. The human AF cells showed morphological changes from round cytoplasm to spindle-like shapes. ***p < 0.001 vs. naïve AF cells (control). #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p <0.001. Scale bar = 200 μm.

In this study, to evaluate the effect of the MCM concentration gradient on the kinetic response of human AF cells, cells were maintained in the MCM concentration gradient (from normalized concentrations of 0 to 1.0) for 72 h in the spine-on-a-chip. Actin-stained images show the morphological change in human AF cells from rounded shape to spindle-like cells with the increasing concentration of MCM [Fig. 4(d)]. The cytoplasm width: height ratio of human AF cells showed a tendency to increase with the increasing concentration of MCM. Specifically, at 0.75 and 1.0 MCM concentrations, human AF cells showed a significant increase compared to basal conditions [Fig. 4(e)].

Concentration of soluble factors derived from macrophage-like THP-1 cells affects kinetic regulation and gene expression of inflammatory mediators and ECM-modifying enzymes on human AF cells in spine-on-a-chip

First, to characterize the macrophage-conditioned medium (MCM) obtained from macrophage-like THP-1 cells, we quantified the production of IL-1β and TNF-α using ELISA. The MCM contained a significantly higher level of TNF-α and IL-1β production compared to normal medium [Fig. 5(a)]. Then, to quantify the morphological alterations of human AF cells with the increasing concentration of MCM, we analysed the kinetic properties of cells including the cell area, growth rate, dendrite length, and migration speed, from acquired time-lapse images using a live-cell imaging system.

FIG. 5.

Kinetic analysis and gene expression of inflammatory mediators and ECM-modifying enzymes on human AF cells stimulated with the soluble factors derived from macrophage-like THP-1 cells. (a) Pro-inflammatory cytokine production in macrophage-conditioned medium. (b) Cell area, (c) growth rate, (d) dendritic extension length, and (e) migration. The kinetic analysis data were measured using a live cell imaging system and Image J software. The gene expression of (f) IL-6, (g) IL-8, (h) MMP-1 and (i) MMP-3. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 vs. naïve AF cells, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 ###p < 0.001.

In regard to the cell area and growth rate, our results demonstrated that human AF cells treated with soluble factors derived from macrophage-like THP-1 cells showed a consistent decrease with the increasing concentration [Figs. 5(b) and 5(c)]. Specifically, the normalized concentration of 0.75 resulted in stunted cell growth. Additionally, at the concentration of 1.0, the cell growth rate showed a significant decrease compared to that at 0.75.

For the dendrite length and migration speed, human AF cells at a concentration of 0.5 expressed a significantly elongated dendrite length compared to the control and the 0.25 group. The dendrite expression of the 0.5 group was maintained up to a concentration of 1.0 [Fig. 5(d)]. Additionally, the migration speed of cells showed a similar tendency in regard to the dendrite length [Fig. 5(e)].

Furthermore, to evaluate the additive effects of TNF-α and IL-1β in MCM on human AF cells in the spine-on-a-chip, the gene expression of inflammatory mediators and ECM-degrading enzymes was measured on human AF cells with the increasing concentration of MCM by qRT-PCR. Our mRNA results for IL-6 and IL-8 showed a dramatic increase in a dose-dependent manner, which is a similar tendency observed in IL-1β stimulation [Figs. 5(f) and 5(g)]. However, interestingly, in ECM-degrading enzymes, human AF cells exposed to MCM revealed addictive effects to the expression of MMP-1 and MMP-3 at the stage of relevantly severe degenerative conditions (high dose of pro-inflammatory cytokines) compared to IL-1β treatment [Figs. 5(h) and 5(i)].

Thus, we demonstrated that the soluble factors derived from macrophages can induce the inflammatory response in human AF cells through alterations in kinetic/molecular expression. Furthermore, the concentration of this factor may act as a key regulator in the progression of IVD degeneration by controlling the expression of several cytokines, catabolic enzymes, and cellular kinetic changes.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we defined a new pathological insight into the grading system of IVD degeneration, whereby IL-1β and soluble factors derived from macrophage-like cells can elicit distinct morphological and molecular responses in different gradient-stimulated human AF cells, using a newly developed spine-on-a-chip.

Degenerated IVD tissues are generally classified into 5 grades (Grade I–V) by conventional MRI T2 spin-echo weight imaging. Although the MRI classification system provides a variety of histologic information including the disc height, water content, and disc homogeneity,7 it fails to reflect the molecular expression of ECM-modifying enzymes, chemokines, and pain modulators. Nevertheless, drugs and anti-cytokine treatment methods depend on the histologic grading system. Additionally, LBP resulting from IVD degeneration is generally thought to arise from nerve root compression originating from the dorsal root ganglion in the spinal cord.30 However, in the presence of radicular pain or sciatica, nerve root compression is occasionally not observed. These clinical phenomena depending on MRI based-classified imaging led us to rethink the mechanisms of IVD degeneration with discogenic pain.

We and other groups previously showed that IL-1β stimulation of human AF cells is strongly linked to the pathogenesis of IVD degeneration.11–13,18,19,31 We also previously demonstrated that the macrophage-mediated soluble factors execute similar functions in regulating inflammatory response and promoting catabolic matrix degradation in human AF cells.18,19,31 Other groups also showed that pro-inflammatory cytokines induce the expression of ECM-degrading enzymes and collagen synthesis,32–35 which is responsible for the severity of IVD degeneration. In this study, we showed that a modified concentration of IL-1β and macrophage soluble factor, similar to that reported during the progression of IVD degeneration, transmutes the expression of pain-related cytokines, chemokines, and matrix catabolic enzymes such as IL-6, IL-8, and MMPs in human AF cells.

Culturing human AF cells in the presence of IL-1β led to increased production of the pain-related cytokine IL-6 in a dose-dependent manner. IL-6 is an inflammatory mediator that can induce mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia. Other studies showed that this mediator's expression levels were consistently increased with increasing disease severity,26,36 but the initiator for this increase has remained unknown. Our data suggest that the concentration of IL-1β is strongly linked to the expression degree of IL-6, and thus, IL-1β may be an initiating factor for IL-6 secretion in human AF cells.

IL-8, known as chemokine C-X-C motif ligand 8 (CXCL8), is a chemokine for infiltrating and activating neutrophils and macrophages, and it is known to be a potent regulator of angiogenesis.37,38 In the early stages of IVD degeneration, this chemotactic factor from the IVD cells promotes infiltrating and activation of immune cells in tissue. With more advanced degeneration, the infiltrated immune cells contribute to the further amplified inflammatory reaction through the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines.39,40 Furthermore, a recent study reported the interaction between human AF cells and endothelial cells, which are target cells of IL-8 and are primarily responsible for angiogenesis. The interactions stimulate the irritation of neurons derived from DRG through production of nerve innervation mediators, which are considered a major initiator of discogenic pain.41,42 This evidence suggests that IL-8 may play a major role in the late stage of degeneration, which is a severely degenerate IVD condition accompanied by pain. Consistent with their findings, our results showed that production of IL-8 is significantly higher in severely degenerate (0.75 and 1.0 ng/ml) compared to mildly degenerate (0.25 and 0.5 ng/ml) conditions. Together, our findings suggest a direct linkage between the concentration of IL-1β, pain-related factor, and chemotactic factor. Furthermore, the concentration of IL-1β in the early and late stages of IVD degeneration may act as a key regulator by modulating the expression of other cytokines, as recently reported by Phillips et al.43

In general, the pathogenesis of IVD degeneration encompasses the modification of ECM and morphological and/or kinetic changes in IVD cells. Human AF cells cultured in the presence of dose-gradient IL-1β markedly increased their expression of matrix degrading enzymes such as MMPs. MMPs expression showed differential responses to dose-gradient IL-1β stimulation dependent on the MMP type. Our data showed that MMP-1 expression showed a steady increase with increasing IL-1β dose. Consistent with our result, Xu et al. observed that MMP-1 expression is gradually up-regulated with the increase in degenerative IVD grade.44 Interestingly, however, human AF cells showed the highest production of MMP-3 after treatment with the lowest concentration of IL-1β (0.25 ng/ml) in this study. Other groups also observed up-regulated MMP-3 expression in early degeneration of cartilage, and it was down-regulated in the late stages of the disease.45 MMPs are a very large family of Ca2+-dependent, zinc-containing proteins.46 MMPs are classified by their substrate affinity and specificity. MMP-1, as collagenases, dominantly cleaves collagen fibres. MMP-3, belonging to stromelysins, can proteolyse aggrecan proteoglycan, which is an ECM component with a high capacity for maintaining the water content in IVD tissue.20,47–49 Furthermore, a recent study demonstrated that acidic pH-induced IL-1β might relate the expression of pain-related markers such as IL-6, nerve growth factor (NGF), and brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), as well as catabolic enzymes MMPs in NP cells.23 On the basis of the evidence, our study suggests that the dose-gradient IL-1β stimulation associated with the severity of IVD degeneration may modulate the differential expression of catabolic response in human AF cells. We also speculate that human AF cells may predominantly express the different types of catabolic enzymes in order to maintain an appropriate response to alterations in pro-inflammatory cytokine concentration, similar to that reported within graded-based degenerative IVD.44,50–53 Our results suggest that MMP-3 may dominantly act in the early stages of IVD degeneration and MMP-1 plays a major role in the late stage. As mentioned above, the catabolic cascade, as well as inflammatory response, is known to be mediated by infiltrating and activation of macrophages or neutrophils, which have the capacity for pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion (e.g., IL-1β and TNF-α).

Thus, in this study, we developed the microfluidic gradient spine-on-a-chip for the application of the macrophage-mediated IVD degeneration process. Our study shows for the first time the differential kinetic response of human AF cells stimulated with a dose-gradient soluble factor derived from the macrophage using the spine-on-a-chip. We previously identified that soluble factors from activated macrophage THP-1 cells include several pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and TNF-α, and induce an inflammatory response in human AF cells.18,19 In this study, our kinetic data showed that the cell cytoplasm area and the growth rate of human AF cells exposed to differential concentrations of MCM were decreased in a dose-dependent manner, suggesting a role in cell viability and proliferation. Interestingly, both the cell dendrite length and the migration speed were markedly increased inbetween the mild and severe degenerate phases, and the morphology was converted from rounded to spindle-like cells, similar to those found in the wound-healing inflammation micro-environment.54–56 Together, the data demonstrate that identifying the molecular and phenotypic alteration related to the severity of IVD degeneration may be a fundamental therapeutic target for ameliorating or preventing symptomatic disc degeneration.

Although the human AF cell phenotype is important for the initiation mechanism of pain-related IVD degeneration, the microenvironment of IVD degeneration is multifactorial, including a variety of types of cells including AF, NP, vascular structure, nerve cells, and extracellular conditions (this is reason that our platform has two connected chambers and one isolated chamber by the hydrogel channel, which implies the histological structure of the IVD). Thus, further studies will need to elucidate the cellular microenvironment in IVD degeneration. Furthermore, it will also be important to investigate the interaction between IVD, vasculature, and nerve cells, which results in activation of pain-related molecular cascades including brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and nerve growth factor (NGF) in discogenic pain. Such studies would provide a more analogous microenvironment compared to those of patients with IVD degeneration, and the newly developed spine-on-a-chip in this study is useful in order to mimic the IVD microenvironment.

Our study shows for the first time that the concentration of pro-inflammatory cytokines is strongly linked to the severity of IVD degeneration. It stimulates the human AF cells to change the cellular phenotype observed during the progression of IVD degeneration, including decreased cell growth, increased migration speed, dendritic length, catabolic mediator, and pain-related cytokine expression. In this study, our data also showed that the molecular expression patterns and cellular phenotypic changes were induced by increasing the initiating factors using a newly developed spine-on-a-chip. It will provide fundamental information regarding the pathology of IVD degenerative progression, and inhibition will be a useful therapeutic target for IVD treatment.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

See supplementary material for simulating the diffusion and gradient profile on spine-on-a chip in this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The manuscript submitted does not contain information about medical device(s)/drug(s). No benefits in any form have been or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this manuscript. This study was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2017R1D1A1A09000962). This work was approved by Korea University Guro Hospital Institutional Review Board.

The authors have stated explicitly that there are no conflicts of interest in connection with this article.

References

- 1. Maniadakis N. and Gray A., “ The economic burden of back pain in the UK,” Pain 84, 95–103 (2000). 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00187-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vos T. et al. , “ Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010,” Lancet 380, 2163–2196 (2013). 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sakai D. et al. , “ Exhaustion of nucleus pulposus progenitor cells with ageing and degeneration of the intervertebral disc,” Nat. Commun. 3, 1264 (2012). 10.1038/ncomms2226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Urban J. P. and Roberts S., “ Degeneration of the intervertebral disc,” Arthritis Res. Ther. 5, 120 (2003). 10.1186/ar629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huang Y.-C., Urban J. P., and Luk K. D., “ Intervertebral disc regeneration: Do nutrients lead the way?,” Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 10, 561–566 (2014). 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sakai D. and Andersson G. B., “ Stem cell therapy for intervertebral disc regeneration: Obstacles and solutions,” Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 11, 243–256 (2015). 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yu L.-P., Qian W.-W., Yin G.-Y., Ren Y.-X., and Hu Z.-Y., “ MRI assessment of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration with lumbar degenerative disease using the Pfirrmann grading systems,” PLoS One 7, e48074 (2012). 10.1371/journal.pone.0048074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Puertas E. B., Yamashita H., Oliveira V. M. D., and Souza P. S D., “ Classification of intervertebral disc degeneration by magnetic resonance,” Acta Ortop. Bras. 17, 46–49 (2009). 10.1590/S1413-78522009000100009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Adams M. A. and Roughley P. J., “ What is intervertebral disc degeneration, and what causes it?,” Spine 31, 2151–2161 (2006). 10.1097/01.brs.0000231761.73859.2c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Freemont A. et al. , “ Nerve ingrowth into diseased intervertebral disc in chronic back pain,” Lancet 350, 178–181 (1997). 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02135-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hu B. et al. , “ Heme oxygenase-1 attenuates IL-1β induced alteration of anabolic and catabolic activities in intervertebral disc degeneration,” Sci. Rep. 6, 21190 (2016). 10.1038/srep21190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Risbud M. V. and Shapiro I. M., “ Role of cytokines in intervertebral disc degeneration: Pain and disc content,” Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 10, 44–56 (2014). 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shen J. et al. , “ IL-1β induces apoptosis and autophagy via mitochondria pathway in human degenerative nucleus pulposus cells,” Sci. Rep. 7, 41067 (2017). 10.1038/srep41067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang H. et al. , “ TGF-βl suppresses inflammation in cell therapy for intervertebral disc degeneration,” Sci. Rep. 5, 13254 (2015). 10.1038/srep13254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Le Maitre C. L., Freemont A. J., and Hoyland J. A., “ The role of interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis of human intervertebral disc degeneration,” Arthritis Res. Ther. 7, R732 (2005). 10.1186/ar1732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Le Maitre C. L., Hoyland J. A., and Freemont A. J., “ Catabolic cytokine expression in degenerate and herniated human intervertebral discs: IL-1β and TNFα expression profile,” Arthritis Res. Ther. 9, R77 (2007). 10.1186/ar2275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. David S. and Kroner A., “ Repertoire of microglial and macrophage responses after spinal cord injury,” Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12, 388–399 (2011). 10.1038/nrn3053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hwang M. H. et al. , “ Photobiomodulation on human annulus fibrosus cells during the intervertebral disk degeneration: Extracellular matrix-modifying enzymes,” Lasers Med. Sci. 31, 767–777 (2016). 10.1007/s10103-016-1923-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hwang M. H. et al. , “ Low level light therapy modulates inflammatory mediators secreted by human annulus fibrosus cells during intervertebral disc degeneration in vitro,” Photochem. Photobiol. 91, 403–410 (2015). 10.1111/php.12415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yang C. et al. , “ Differential expression of p38 MAPK α, β, γ, δ isoforms in nucleus pulposus modulates macrophage polarization in intervertebral disc degeneration,” Sci. Rep. 6, 22182 (2016). 10.1038/srep22182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guan P.-P. et al. , “ The role of cyclooxygenase-2, interleukin-1β and fibroblast growth factor-2 in the activation of matrix metalloproteinase-1 in sheared-chondrocytes and articular cartilage,” Sci. Rep. 5, 10412 (2015). 10.1038/srep10412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wuertz K. and Haglund L., “ Inflammatory mediators in intervertebral disk degeneration and discogenic pain,” Global Spine J. 3, 175–184 (2013). 10.1055/s-0033-1347299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gilbert H. T., Hodson N., Baird P., Richardson S. M., and Hoyland J. A., “ Acidic pH promotes intervertebral disc degeneration: Acid-sensing ion channel-3 as a potential therapeutic target,” Sci. Rep. 6, 37360 (2016). 10.1038/srep37360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Feng C. et al. , “ Disc cell senescence in intervertebral disc degeneration: Causes and molecular pathways,” Cell Cycle 15, 1674–1684 (2016). 10.1080/15384101.2016.1152433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Grogan S. P. and D'Lima D. D., “ Joint aging and chondrocyte cell death,” Int. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 5, 199–214 (2010). 10.2217/ijr.10.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Burke J. et al. , “ Intervertebral discs which cause low back pain secrete high levels of proinflammatory mediators,” Bone Jt. J. 84, 196–201 (2002). 10.1302/0301-620X.84B2.12511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ahn S.-H. et al. , “ mRNA expression of cytokines and chemokines in herniated lumbar intervertebral discs,” Spine 27, 911–917 (2002). 10.1097/00007632-200205010-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pellicoro A., Ramachandran P., Iredale J. P., and Fallowfield J. A., “ Liver fibrosis and repair: Immune regulation of wound healing in a solid organ,” Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14, 181 (2014). 10.1038/nri3623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gurtner G. C., Werner S., Barrandon Y., and Longaker M. T., “ Wound repair and regeneration,” Nature 453, 314 (2008). 10.1038/nature07039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Boos N. et al. , “ Classification of age-related changes in lumbar intervertebral discs: 2002 Volvo Award in basic science,” Spine 27, 2631–2644 (2002). 10.1097/00007632-200212010-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kim J. H. et al. , “ Effect of biphasic electrical current stimulation on IL-1β–stimulated annulus fibrosus cells using in vitro microcurrent generating chamber system,” Spine 38, E1368–E1376 (2013). 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182a211e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tian Y. et al. , “ Inflammatory cytokines associated with degenerative disc disease control aggrecanase-1 (ADAMTS-4) expression in nucleus pulposus cells through MAPK and NF-κB,” Am. J. Pathol. 182, 2310–2321 (2013). 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.02.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang J. et al. , “ TNF-α and IL-1β promote a disintegrin-like and metalloprotease with thrombospondin type I motif-5-mediated aggrecan degradation through syndecan-4 in intervertebral disc,” J. Biol. Chem. 286, 39738–39749 (2011). 10.1074/jbc.M111.264549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Séguin C. A., Pilliar R. M., Roughley P. J., and Kandel R. A., “ Tumor necrosis factorα modulates matrix production and catabolism in nucleus pulposus tissue,” Spine 30, 1940–1948 (2005). 10.1097/01.brs.0000176188.40263.f9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bian Q. et al. , “ Excessive activation of TGFβ by spinal instability causes vertebral endplate sclerosis,” Sci. Rep. 6, 27093 (2016). 10.1038/srep27093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Murata Y. et al. , “ Local application of interleukin-6 to the dorsal root ganglion induces tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the dorsal root ganglion and results in apoptosis of the dorsal root ganglion cells,” Spine 36, 926–932 (2011). 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181e7f4a9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Huang Q., “ IL-17 promotes angiogenic factors IL-6, IL-8, and vegf production via stat1 in lung adenocarcinoma,” Sci. Rep. 6, 36551 (2016). 10.1038/srep36551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pozzobon T. et al. , “ Treponema pallidum (syphilis) antigen TpF1 induces angiogenesis through the activation of the IL-8 pathway,” Sci. Rep. 6, 18785 (2016). 10.1038/srep18785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang J. et al. , “ Tumor necrosis factor α–and interleukin‐1β–dependent induction of CCL3 expression by nucleus pulposus cells promotes macrophage migration through CCR1,” Arthritis Rheum. 65, 832–842 (2013). 10.1002/art.37819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kawaguchi S. et al. , “ Chemokine profile of herniated intervertebral discs infiltrated with monocytes and macrophages,” Spine 27, 1511–1516 (2002). 10.1097/00007632-200207150-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moon H. J. et al. , “ Effects of secreted factors in culture medium of annulus fibrosus cells on microvascular endothelial cells: Elucidating the possible pathomechanisms of matrix degradation and nerve in-growth in disc degeneration,” Osteoarthritis Cartilage 22, 344–354 (2014). 10.1016/j.joca.2013.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pohl P. H. et al. , “ Catabolic effects of endothelial cell‐derived microparticles on disc cells: Implications in intervertebral disc neovascularization and degeneration,” J. Orthop. Res. 34, 1466–1474 (2016). 10.1002/jor.23298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Phillips K. et al. , “ Potential roles of cytokines and chemokines in human intervertebral disc degeneration: Interleukin-1 is a master regulator of catabolic processes,” Osteoarthritis Cartilage 23, 1165–1177 (2015). 10.1016/j.joca.2015.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Xu H. et al. , “ Correlation of matrix metalloproteinases-1 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 with patient age and grade of lumbar disk herniation,” Cell Biochem. Biophys. 69, 439–444 (2014). 10.1007/s12013-014-9815-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Aigner T., Zien A., Gehrsitz A., Gebhard P. M., and McKenna L., “ Anabolic and catabolic gene expression pattern analysis in normal versus osteoarthritic cartilage using complementary DNA–array technology,” Arthritis Rheumatol. 44, 2777–2789 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Khokha R., Murthy A., and Weiss A., “ Metalloproteinases and their natural inhibitors in inflammation and immunity,” Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13, 649–665 (2013). 10.1038/nri3499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Itoh Y., “ Membrane-type matrix metalloproteinases: Their functions and regulations,” Matrix Biol. 44, 207–223 (2015). 10.1016/j.matbio.2015.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Vacek T. P. et al. , “ Matrix metalloproteinases in atherosclerosis: Role of nitric oxide, hydrogen sulfide, homocysteine, and polymorphisms,” Vasc. Health Risk Manage. 11, 173 (2015). 10.2147/VHRM.S68415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hu J., Van den Steen P. E., Sang Q.-X. A., and Opdenakker G., “ Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors as therapy for inflammatory and vascular diseases,” Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 6, 480–498 (2007). 10.1038/nrd2308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wei F. et al. , “ In vivo experimental intervertebral disc degeneration induced by bleomycin in the rhesus monkey,” BMC Musculoskeletal Disord. 15, 340 (2014). 10.1186/1471-2474-15-340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tang Y., Wang S., Liu Y., and Wang X., “ Microarray analysis of genes and gene functions in disc degeneration,” Exp. Ther. Med. 7, 343–348 (2014). 10.3892/etm.2013.1421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sobajima S. et al. , “ Quantitative analysis of gene expression in a rabbit model of intervertebral disc degeneration by real-time polymerase chain reaction,” Spine J. 5, 14–23 (2005). 10.1016/j.spinee.2004.05.251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Xu H., Mei Q., Xu B., Liu G., and Zhao J., “ Expression of matrix metalloproteinases is positively related to the severity of disc degeneration and growing age in the East Asian lumbar disc herniation patients,” Cell Biochem. Biophys. 70, 1219–1225 (2014). 10.1007/s12013-014-0045-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tomasek J. J., Gabbiani G., Hinz B., Chaponnier C., and Brown R. A., “ Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling,” Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 349–363 (2002). 10.1038/nrm809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Page-McCaw A., Ewald A. J., and Werb Z., “ Matrix metalloproteinases and the regulation of tissue remodelling,” Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 221–233 (2007). 10.1038/nrm2125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Reilkoff R. A., Bucala R., and Herzog E. L., “ Fibrocytes: Emerging effector cells in chronic inflammation,” Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11, 427–435 (2011). 10.1038/nri2990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

See supplementary material for simulating the diffusion and gradient profile on spine-on-a chip in this study.