Abstract

We detail study design options that generalize case–control sampling when longitudinal outcome data are already collected as part of a primary cohort study, but new exposure data must be retrospectively processed for a secondary analysis. Furthermore, we assume that cost will limit the size of the subsample that can be evaluated. We describe a novel class of stratified outcome–dependent sampling designs for longitudinal binary response data where distinct strata are created for subjects who never, sometimes, and always experienced the event of interest during longitudinal follow-up. Individual designs within this class are differentiated by the stratum-specific sampling probabilities. We show for parameters associated with time-varying exposures, subjects who experience the event/outcome at some but not at all of the follow-up times (i.e., those who exhibit response variation) are highly informative. If the time-varying exposure varies exclusively within individuals (i.e., intraclass correlation coefficient is 0), then sampling all subjects with response variability can yield highly precise parameter estimates even when compared to an analysis of the original cohort. The flexibility of the designs and analysis procedures also permits estimation of parameters that correspond to time-fixed covariates, and we show that with an imputation–based estimation procedure, baseline covariate associations can be estimated with very high precision irrespective of the design. We demonstrate features of the designs and analysis procedures via a plasmode simulation using data from the Lung Health Study.

Keywords: outcome–dependent sampling, case–control, enrichment sampling, longitudinal data, binary data, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic bronchitis

INTRODUCTION

We describe a novel class of study designs and associated analysis procedures for longitudinal binary response data [1, 2, 3]. The designs can be used in settings where the response and basic covariate data are available, but an expensive exposure variable must be ascertained retrospectively in order to conduct a new study. To generalize case–control sampling we propose a stratified sampling based on three strata (0, 1, and 2) empirically defined by summarizing each subject’s response over time into a simple total count. With Yij denoting the binary response value for subject i at observation number j, and ni the number of times subject i was observed, we define stratum 0, 1, and 2 with Σj Yij = 0, 0 < Σj Yij < ni, and Σj Yij = ni, respectively. Within this class of stratified sampling designs, we assign members of a stratum (r) a common sampling probability, π(r), r = 0, 1, or 2, and alternative designs are distinguished by the choices for the stratum-specific sampling probabilities: π(0), π(1), and π(2).

An important feature of longitudinal data arises from the fact that both response and exposure variability may result from within-subject changes over time, or from subject-to-subject variability. In this paper, we will show that who is informative (i.e., which strata should be sampled with high probability) depends upon the response-exposure associations that are of interest. We emphasize the importance of considering the empirical sources of exposure and response variability (between-subject and within-subject) when conducting the designs.

To demonstrate the utility of the designs, we use data collected at annual clinic visits from the Lung Health Study [4, 5, 6]. The Lung Health Study protocols were approved by the institutional review boards at each participating clinical center and participants were enrolled after written informed consent was obtained. Based on genetic associations observed with chronic bronchitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in smokers [7], the exemplar analysis will examine the short term, causal effect of current smoking on chronic bronchitis risk in those with and without at least one T allele on single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs7671167, and the difference between the two effects. Importantly, it will also study the extent to which other, baseline characteristics are risk factors for chronic bronchitis.

The Lung Health Study collected genetic, covariate, and outcome data for all participants and made them available on the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database of genotypes and phenotypes (dbGaP [8]; access number phs000335.v2.p2). Links to instruction pages for downloading dbGaP data are provided in the eAppendix. We use a subset of Lung Health Study data to conduct a plasmode simulation study [9] that examines the utility of the proposed retrospective study designs under scenarios where the longitudinal outcome and covariate data are available on all subjects but genetic data must be ascertained retrospectively at a sample size limiting cost.

ESTIMANDS AND ESTIMATORS FOR THE LUNG HEALTH STUDY ANALYSIS

The population represented by Lung Health Study [5] participants is middle-aged smokers with mild to moderate COPD. Although the Lung Health Study was a randomized clinical trial that examined smoking cessation interventions, treatment allocation was not available to us. For this analysis, we seek to emulate a hypothetical sequentially randomized study where participants are randomized to be a smoker or non-smoker at different longitudinal follow-up visits. We therefore conduct a multiple logistic regression analysis that adjusts or controls for potential confounders of the smoking–chronic bronchitis relationship and other baseline characteristics that are also of scientific interest for their association with chronic bronchitis. Our primary goal with these data is to illustrate possible novel sampling designs that could be used to efficiently evaluate a new candidate biomarker that may predict chronic bronchitis or may modify the effect of smoking.

Let μij = Pr[CBij = 1 | Xij] be the prevalence of chronic bronchitis in a population defined by subject i’s covariate values Xij at the jth visit, and let smkij be a 0/1 indicator of current smoking. In the analysis dataset, smkij varies both within and between individuals (intracluster correlation coefficient=0.82), and for this reason we adopt the ’between–within’ model described in Neuhaus and Kalbfleisch (1998) [10] to partition exposure variability. The between–within model decomposes smkij into two components, one that varies exclusively within and the other that varies exclusively between individuals. Specifically, let , then we can write smkij = (smkij − smkb,i) + smkb,i = smkw,ij + smkb,i. Thus, ICC(smkw,ij) = 0 and ICC(smkb,i) = 1, and the two components can be modeled separately. For the Lung Health Study analysis, the analytical model is given by:

| (1) |

where snpi = 1 (0) if the T allele is present (absent) at rs7671167, and cij is a vector of confounders and other risk factors that includes: baseline covariates lifetime pack–years smoked, average number of cigarettes smoked per day prior to the Lung Health Study, gender, age, body mass index (BMI), and nine site-specific indicator variables; and the time-varying covariate, study year. Notice that βws corresponds to a difference in the log odds ratio for smokers (vs. non-smokers) between those with and without the T allele. Because the estimate was very close to 0, we excluded the interaction between snpi and smkb,i in this between–within model.

Although the between–within model is not a standard data-generating, causal model [11, 12], it is popular in longitudinal analyses and has been shown to be useful for estimating causal effects under specific assumptions. For example, consider a simplified version of (1), and assume the true model is given by logit(μij) = β0 + α · smkij + βuui ≡ β0 + α · smkw,ij + α · smkb,i + βuui so that βw = βb. Also assume that the subject level confounder ui is unmeasured and the model fit to the data is . The estimate of βw is consistent for α as long as ui has a linear relationship with smkb,i [13]. Fitting the standard model results in an inconsistent estimate of α. This estimate of βw has exhibited robustness to the ’linear with the average’ criterion [12] although it has shown sensitivity to high levels of heteroscedasticity [14] and can potentially induce confounding due to conditioning on a collider [15, 16]. For the purpose of providing insights into the operating characteristics of the study designs, we assume the between–within model assumptions are not violated in a severe way. A key benefit of the model is the explicit decomposition of smkij into smkw,ij and smkb,i which vary exclusively within-subjects (ICC = 0) and between-subjects (ICC = 1), respectively. Design considerations for between- and within-subject covariate effects will be shown to be quite different.

Lung Health Study Cohort

Table 1 shows demographic and other characteristics of 3932 participants. Seventy-six percent of participants possessed at least one T allele at rs7671167. The vast majority were observed at four follow-up visits, and at each visit, between 71 and 76 percent were smokers. Chronic bronchitis occurred in 28 to 29 percent of visits. In all, 2064 participants never experienced chronic bronchitis, 1404 experienced it at some but not all visits, and 464 experienced chronic bronchitis at all visits.

Table 1.

Demographics and features of the Lung Health Study cohort at baseline and over the course of four annual visits to study clinics: Continuous variable are summarized with the [5: 25: 50: 75: 95]th percentiles, and categorical variables are summarized with proportions or raw numbers observed. Cigarettes per day captures the number of cigarettes per day prior to enrolling in the Lung Health Study.

| Variable | Patient-level | Year 0 | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 3932 | ||||

| Patient-level summaries | |||||

| Age (years) | [37: 43: 49: 54: 58] | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | [20: 23: 25: 28: 33] | ||||

| Pack years | [17: 28: 37: 50: 76] | ||||

| Cigarettes/day | [10: 20: 30: 40: 55] | ||||

| Proportion female | 0.37 | ||||

| Proportion with ≥ T allele | 0.76 | ||||

| Number smoking | |||||

| At no visits | 750 | ||||

| At some visits | 623 | ||||

| At all visits | 2559 | ||||

| Number with chronic bronchitis | |||||

| At no visits (R=0) | 2064 | ||||

| At some visits (R=1) | 1404 | ||||

| At all visits (R=2) | 464 | ||||

| Longitudinal summaries | |||||

| Number observed | 3932 | 3859 | 3845 | 3930 | |

| Proportion smoking | 0.76 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.71 | |

| Proportion with chronic bronchitis | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.28 |

DESIGN

To formalize the design options, assume a representative cohort of N participants with longitudinal binary outcomes and observed covariate data. In the Lung Health Study, Yij is the binary indicator for presence/absence of chronic bronchitis for subject i at visit j, and ni is the number of times that subject i was observed. Assume additional measurement is needed to obtain a new exposure variable (e.g., snpi), and ascertainment costs limit sample size. Thus, for subject i, Xi = (Xei, Xoi) represents the complete design matrix, but Xei is not available initially. Finally, Xij is the covariate vector for subject i at visit j.

We proposed [1, 2] stratified outcome–dependent sampling designs to identify subjects for retrospective Xei ascertainment. Strata are defined by the subject-specific response sum, Σj yij. Stratum 0, 1, and 2 is comprised of subjects who had events at none, some, and all follow-up visits, respectively. Within stratum R = r, there are Nr subjects and each is sampled with probability π(r) which is a design parameter under the control of the investigators and controls the magnitude of possible oversampling within select strata. The sampling probabilities result in an expected sample size from stratum r equal to . We denote unique candidate designs with indicating the size of the subsample taken from each stratum.

For the estimation of time-varying covariate regression parameters, including interactions with time-varying covariates, we have previously shown that subjects with any outcome variability (i.e., those belonging to stratum R = 1) are more informative than those who have constant responses over time [1, 2]. The information difference between subjects with and without variation in their longitudinal outcomes is particularly large if the time-varying covariates vary exclusively within subjects (i.e., intraclass correlation coefficient equals 0) where subjects in strata 0 and 2 provide little to no information. In our example data this is the case for the within-subject smoking variable where the intraclass correlation coefficient was, by construction, equal to 0. To the extent that there exists between subject variability in a covariate that is of interest, subjects in strata 0 and 2 may provide information regarding the exposure–outcome association.

MODEL

Although the general design ideas apply to a broad class of models, we focus on “marginalized models” [17, 18, 19] for binary response data. Marginalized models, like generalized linear mixed models ([20, 21]), can be estimated with likelihood-based approaches. However, in contrast to conditional generalized linear mixed models, marginalized models estimate marginal model parameters similar to generalized estimating equations [22, 23]. Given Yi and Xi, the marginal mean model is

| (2) |

where βm is a p–dimensional parameter vector. While this model specifies the (marginal) mean of the distribution [Yi|Xi], to fully identify [Yi|Xi], we construct a second regression model to characterize within-subject response association. We refer to the second regression component as the conditional mean or response dependence model. In this paper we use the marginalized transition and latent variable model [24] where the response dependence model is

| (3) |

The value Δij can be thought of as an intercept in a logistic regression model that includes a transition or Markov term Yij−1 and a random intercept bi. This response dependence model is appealing because with longitudinal data, it is common to observe both serial response dependence that decays with time separations, and long-range dependence that is captured with the random intercept. A more thorough description of marginalized models and specifically Δij can be found in [18, 25, 24].

ESTIMATION

Within the proposed class of outcome–dependent sampling designs, we deliberately oversample informative subjects, resulting in a non-reprentative study sample. For example, in many cases the sample will be over-represented with members of stratum 1 in order to maximize efficiency. Therefore, to validly estimate regression parameters based on the targeted sample we consider three estimation strategies: ascertainment–corrected maximum likelihood, weighted likelihood, and multiple imputation, which we briefly detail.

Ascertainment–Corrected Maximum Likelihood

Let θ = {βm, α}, where α ≡ (γ, σ), be the parameter vector from a marginalized model and let L(θ|Yi, Xi) = Li = Pr(Yi|Xi;|θ) be the likelihood contribution by subject i under random sampling. An ascertainment–corrected likelihood under the proposed design can be calculated via Bayes’ theorem with

| (4) |

where Li2 and Li0 are the likelihood contributions by subject i under random sampling had Σjyij = ni and Σj yij = 0, respectively, π(r) is the probability of being sampled for all members of stratum R=r, Si = 1 if subject i is sampled, and Si = 0 if not. Ascertainment–corrected maximum likelihood maximizes (4) and we are able to estimate parameters in the original model, i.e., θ in Pr(Yi|Xi; θ). Notice that this ascertainment–corrected likelihood is similar to the conditional logistic regression likelihood with the exception that we condition on being sampled (Si = 1) rather than on Σj yij. While conditional logistic regression is useful in many settings, it cannot estimate baseline covariate effects that are of secondary interest in the Lung Health Study analysis. Further, conditional logistic regression implicitly assumes a random intercept structure (approximately exchangeable correlation), which may be overly simplistic for longitudinal data that often possess serial dependence.

Weighted Likelihood

One of the most common approaches to addressing selection bias induced by design-based oversampling is inverse probability weighting (IPW) [26, 27]. IPW can be used to correct the standard likelihood score equations (i.e., the derivative of the log likelihood) by weighting by the inverse of the subject-specific probability of having been sampled, π(ri) which must equal one of π(0), π(1), or π(2). Parameters are estimated by solving the weighted log-likelihood score equation, Σi[π(ri)−1 · ∂ log(Li)/∂θ] = 0, and robust standard errors [26, 27, 22] are used to estimate uncertainty.

Multiple Imputation

A weakness of ascertainment–corrected maximum likelihood and weighted likelihood is that even though (Y, Xo) are available on all subjects, the only information used in parameter estimation and inference is from subjects selected into the subsample for whom Xei is also available (i.e., those with Si = 1). One of the primary strengths of multiple imputation [28, 29] is its efficient use of all available data. This suggests that we may impute Xei for subjects not selected for detailed exposure evaluation (i.e., those for whom Si = 0). There are different approaches for building the required imputation model, and in the eAppendix we detail the specific imputation strategy that we use for the present analyses.

RESULTS FROM ANALYSES OF THE LUNG HEALTH STUDY

We illustrate the potential advantages of an outcome–dependent sampling design over random sampling using the Lung Health Study cohort. We are interested in risk factors for chronic bronchitis, and in particular, the impact of current smoking for those with and without at least one copy of the T allele at rs7671167. Equation 1 shows the regression model. While the primary estimation targets are βw, βws, and βw + βws, we are also interested in other covariate associations with chronic bronchitis risk (i.e., those described by the parameter βc).

Chronic bronchitis was captured on the Lung Health Study annual questionnaire, and CBij = 1 if subject i experienced chronic bronchitis (at least three months of a phlegm-producing cough) in the year preceding visit j. The smoking variable, smkij, was set to 1 if the participant tested positive on a cotinine test at the prior (j − 1) or present (j) visit. Otherwise, smkij = 0. We used this definition primarily to improve the likelihood that those with smkij = 0 were, in fact, non-smokers. One disadvantage of this approach is that we removed the first annual follow-up visit from the analysis because all subjects smoked prior to the study.

Designs And Analysis Procedures

Even though the Lung Health Study genotyped all subjects, we are interested in circumstances where we may only genotype a subset. For illustration we assume that approximately 1600 of the 3932 subjects can be genotyped, and we investigate several targeted designs. With random sampling we randomly selected 1600 subjects to be included for genotyping. The other designs we considered were outcome–dependent sampling designs: D[100, 1400, 100], D[275, 1050, 275], and D[450, 700, 450]. We sampled individuals independently, and in light of the stratum sizes (see Table 1), sampling probabilities for the three outcome–dependent sampling designs were: [0.048, 0.997, 0.216], [0.133, 0.748, 0.593], and [0.218, 0.499, 0.970]. Importantly, D[100, 1400, 100] sampled effectively all participants in stratum 1, and so it includes all subjects who exhibited response variation over the course of the study. Results from earlier work suggest that this design can yield high precision for time-varying covariate effect estimates (e.g., for βw and βws). After conducting each of the three outcome–dependent sampling study designs, we analyzed the resulting data with ascertainment–corrected maximum likelihood, weighted likelihood, and multiple imputation. When conducting the random sampling design, maximum likelihood using subsampled individuals only and an multiple imputation procedure that imputed Xei in unsampled subjects were used for analyses. We replicated the process of sampling participants from the cohort and analyzing the observed data 500 times. We report averages across the replicates for parameter and uncertainty estimates.

Full Cohort Analysis

In table 2 we show the results from the full cohort logistic regression analysis conducted with standard maximum likelihood and from the random sampling, D[100, 1400, 100], and D[275, 1050, 275] study designs. Under the full cohort analysis, current smoking was highly associated with chronic bronchitis risk, and presence of the T allele modified the effect of smoking. The odds ratio (95% confidence interval) for chronic bronchitis comparing smoking to non-smoking visits was exp(1.25) = 3.49 (2.37, 5.13) in those without the T allele, and exp(1.25 − 0.57) = 1.97 (1.60, 2.44) in those with at least one T allele copy. The ratio of odds ratios for those with and without the T allele was estimated to be exp(−0.57) = 0.57 (0.37, 0.88) consistent with the T allele ameliorating the impact of smoking on chronic bronchitis risk.

Table 2.

Results from the full cohort analysis and 500 replicates of random sampling and the D[100, 1400, 100] and D[275, 1050, 275] designs. We report average estimates and, in parentheses, average estimated standard errors on the log odds ratio (logistic) scale. ML = maximum likelihood, ACML = ascertainment–corrected maximum likelihood, WL = weighted likelihood, MI = multiple imputation.

| Variable | Full cohort | Random sampling | D[100,1400,100] | D[275,1050,275] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML | ML | MI | ACML | WL | MI | ACML | WL | MI | |

| Primary estimation targets | |||||||||

| SNP (βs) | −0.08 (0.07) | −0.09 (0.11) | −0.09 (0.11) | −0.15 (0.15) | −0.10 (0.20) | −0.14 (0.15) | −0.08 (0.12) | −0.08 (0.13) | −0.07 (0.12) |

| Smoking (within; βw) | 1.25 (0.20) | 1.25 (0.31) | 1.24 (0.28) | 1.18 (0.21) | 1.33 (0.30) | 1.27 (0.21) | 1.28 (0.25) | 1.28 (0.25) | 1.28 (0.23) |

| SNP by Smoking (within; βws) | −0.57 (0.22) | −0.57 (0.36) | −0.55 (0.34) | −0.54 (0.23) | −0.63 (0.33) | −0.59 (0.23) | −0.60 (0.28) | −0.59 (0.28) | −0.60 (0.27) |

| Time-varying covariates | |||||||||

| Study year (per 3 years) | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.02) | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.02) | 0.00 (0.01) |

| Time-fixed/baseline covariates | |||||||||

| Smoking (between; βb) | 2.05 (0.10) | 2.06 (0.15) | 2.05 (0.10) | 1.93 (0.21) | 2.09 (0.25) | 2.05 (0.10) | 2.01 (0.15) | 2.07 (0.17) | 2.05 (0.10) |

| Female | −0.15 (0.06) | −0.14 (0.10) | −0.15 (0.06) | −0.21 (0.15) | −0.14 (0.19) | −0.15 (0.06) | −0.17 (0.11) | −0.14 (0.12) | −0.15 (0.06) |

| Cigarettes/day (per 10 cigs/day) | 0.16 (0.02) | 0.16 (0.04) | 0.16 (0.02) | 0.08 (0.05) | 0.16 (0.07) | 0.16 (0.02) | 0.12 (0.04) | 0.16 (0.04) | 0.16 (0.02) |

| Pack years (per 10 pack years) | 0.11 (0.04) | 0.10 (0.06) | 0.11 (0.04) | 0.14 (0.08) | 0.12 (0.12) | 0.11 (0.04) | 0.13 (0.06) | 0.11 (0.08) | 0.11 (0.04) |

| Age (per 10 years) | 0.08 (0.05) | 0.08 (0.08) | 0.08 (0.05) | 0.05 (0.11) | 0.06 (0.15) | 0.08 (0.05) | 0.04 (0.08) | 0.08 (0.09) | 0.08 (0.05) |

| BMI (per 5 kg/m2) | 0.00 (0.04) | 0.00 (0.06) | 0.00 (0.04) | −0.05 (0.09) | −0.01 (0.12) | 0.00 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.07) | 0.00 (0.08) | 0.00 (0.04) |

| Response dependence model | |||||||||

| γ | 0.53 (0.10) | 0.53 (0.15) | 0.53 (0.10) | 0.54 (0.10) | 0.52 (0.10) | 0.53 (0.10) | 0.53 (0.11) | 0.52 (0.11) | 0.53 (0.10) |

| log(σ) | 0.82 (0.04) | 0.82 (0.06) | 0.82 (0.04) | 0.83 (0.07) | 0.80 (0.07) | 0.82 (0.04) | 0.82 (0.05) | 0.82 (0.05) | 0.82 (0.04) |

Subsample Analyses

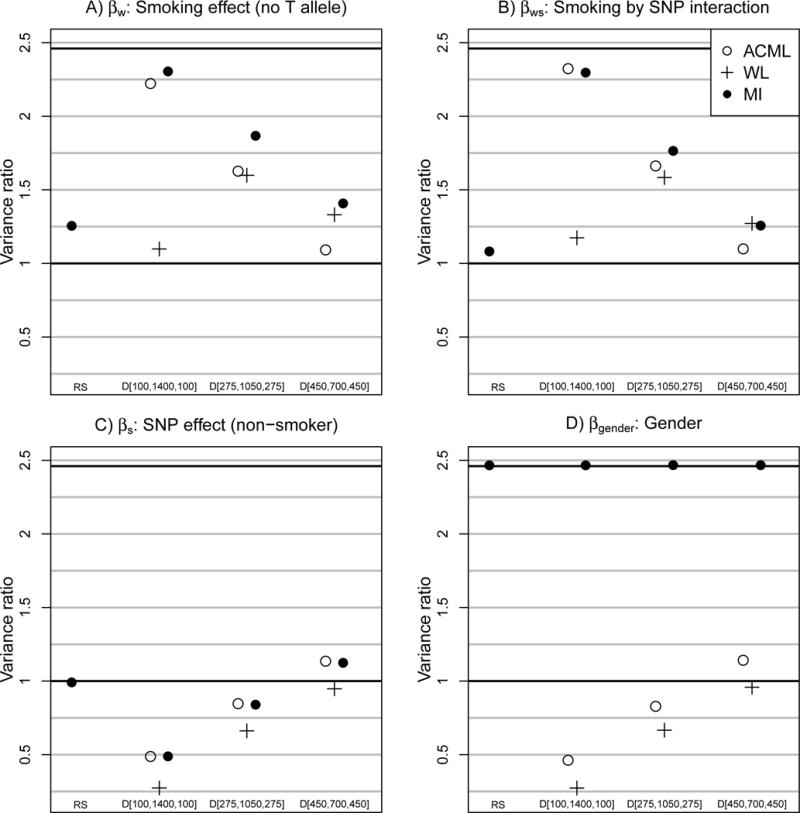

Across 500 replicates, on average, all designs and analysis procedure combinations approximately reproduced the point estimates from the FC analysis (Table 2), so we describe study design by analysis procedure combination performance by comparing the estimated precision. Results are displayed as standard errors for all parameters in Table 2. However, in the Figure we focus on four key parameters in order to gain insights into the utility of the proposed designs. In the Figure, we present the ratio of the average estimated variance using a random sampling design with maximum likelihood analysis to each other design/analysis procedure combination. Thus, for each design/analysis procedure combination, we describe an estimate of ’relative efficiency’ compared to a standard random sampling design and analysis. It is worth noting that the maximum possible efficiency gain over random sampling is 3932/1600 ≈ 2.46 which is the comparison of the maximum likelihood analysis using the full cohort to maximum likelihood analysis using the random sampling design.

Figure 1.

Relative variance: Average estimated variance based on a random sampling design with maximum likelihood analysis divided by average estimated variance based on each design by analysis procedure combination (500 replicates). SNP=single nucleotide polymorphism, ACML=ascertainment–corrected maximum likelihood, MI=multiple imputation, and WL=weighted likelihood.

Figure panels A and B examine time-varying covariate parameters βw and βws, and we observe that with the D[100, 1400, 100] design, both ascertainment–corrected maximum likelihood and multiple imputation estimation procedures are very precise. The impressive precision using a targeted sample with less than half the total cohort is due to two important features of the design and model: 1) nearly all of the 1404 subjects with response variation (i.e., those in stratum 1) are sampled under the design, and 2) all variability in smkw,ij and smkw,ij · snpi occured within subjects. These results are consistent with what we have observed in the past [1, 2]. Estimation precision drops as fewer subjects from stratum 1 are included in the outcome–dependent sampling which is the case with the D[275, 1050, 275] and D[450, 700, 450] designs.

One interesting observation is that for estimates of βw and βws the relative variance pattern was not monotonic for weighted likelihood analysis under the three outcome–dependent sampling designs. Relative variance is highest for the D[275, 1050, 275] design and is lower for D[100, 1400, 100] and D[450, 700, 450]. There appears to be a tradeoff between the study design and weighted likelihood weighting scheme. An extreme design, e.g., D[100, 1400, 100], samples the most informative subjects; however with weighted likelihood, the design induces an extreme weighting scheme that leads to imprecise estimates. Further research is required to find a general solution for this study design–weighting scheme tradeoff.

Figure panels C and D show that the outcome–dependent sampling designs proposed here are not particularly useful if the target of inference is a subject-level or time fixed covariate parameter. For example, D[100, 1400, 100] yields lower precision estimates of βs than random sampling with maximum likelihood analyses, although precision improves as proportionately more subjects are sampled from strata 0 and 2 with D[275, 1050, 275] and D[450, 700, 450].

Even though multiple imputation was not clearly more precise than ascertainment–corrected maximum likelihood for βw, βws, and βs, the utility of multiple imputation is clearly displayed in baseline covariate effects such as βgender. Irrespective of the study design multiple imputation yielded βgender estimates that were as precise as the full cohort analysis since the covariate, gender, is available on all subjects in the dataset, including those who were not included in the outcome–dependent sample. By imputing Xei, we simply allow ourselves to exploit all of the existing data in order to summarize the gender–chronic bronchitis association. Without imputing Xei, we effectively throw away available covariate information.

DISCUSSION

We discussed a class of epidemiologic study designs for longitudinal binary response data that can be viewed as an extension to the case–control design. Rather than using a single scalar response to create two sampling strata (cases and controls), we summarize the response vector to create three sampling strata (no events, some events, all events). By oversampling subjects with response variation, we can obtain substantial precision gains for time–varying covariate effects and for their interactions with baseline variables. Furthermore, supplementing the design with multiple imputation analyses yields near full efficiency for the effects of baseline covariates.

Our work provides two key results: 1) subjects with response variability are highly informative for estimating time-varying covariate effects, or equivalently subjects without response variability are relatively uninformative, and 2) near full efficiency can be obtained for parameters associated with time–varying covariates that vary exclusively within individuals when all subjects with response variability are sampled. Insight into such results is provided by what is known about conditional logistic regression precision for longitudinal binary data. In contrast to random intercepts models, conditional logistic regression only uses within-cluster response and exposure variation to estimate parameters. Generalized linear mixed models ’borrow strength’ by exploiting between– and within–subject variability. As discussed in [30, 10], generalized linear mixed models are more efficient than conditional logistic regression for all parameters except those associated with time-varying covariates that vary exclusively within subjects (i.e., the intracluster correlation in the covariate is 0) where conditional logistic regression and generalized linear mixed models are equally efficient. That is, towards estimating such parameters, only subjects with response variability contribute information. In the Lung Health Study, the within-subject smoking, smkw,ij variable, had intracluster correlation equal to 0. Thus, the D[100, 1400, 100], which sampled nearly all subjects with response variability, yielded very precise estimates of βw and βws.

Even though we were interested in marginal model parameters, one might also be interested in conditional model estimation (e.g., from mixed effects models). If interest is exclusively in βw and βws from a conditional model, Sjölander et al. showed that a highly informative study design and estimation procedure combination is one that samples only those with within–subject response and exposure variability (i.e., those who are doubly discordant) and that conducts analyses with conditional logistic regression [31]. That is, we would sample only those who exhibited CBij and smkij variability over time. Such a design represents a highly resource–efficient approach, and would result in a sample size that is smaller than what we have proposed. Further, it estimates parameters that are analogous to βw and βws. What is lost by conducting such a design and analysis is the ability to estimate other parameters efficiently (or at all), to do prediction, to ’marginalize’ over the exposure distribution to obtain marginal risk contrasts, and also the possibility of invalid inferences when the response dependence model differs from a simple exchangeable structure.

The weighted likelihood analysis procedure is not as efficient as ascertainment–corrected maximum likelihood and multiple imputation procedures in settings we studied. However, it is well known that there is a bias-variance tradeoff between maximum likelihood procedures and weighted likelihood in the presence of model misspecification [32, 33, 34]. Maximum likelihood is more efficient but less robust than weighted likelihood approaches. Such misspecification might arise, for example, if the mean model for [Yi|Xi] ignores an important interaction.

In this manuscript we have assumed that within-subject smoking is not an endogeneous exposure that is influenced by past outcomes. If the primary exposure of interest is driven by past outcomes then tailored statistical methods would be needed that can properly address time-dependent confounding e.g. [35, 36]. Additional research is warranted that considers the potential for efficient outcome–dependent sampling designs in such a complex time-dependent context.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the supported effort of the faculty and staff members of the Johns Hopkins University Bayview Genetics Research Facility, NHLBI grant HL066583 (Garcia/Barnes, PI) and NHGRI grant HG004738 (Barnes/Hansel, PI). The Lung Health Study was supported by U.S. Government contract No. N01-HR-46002 from the Division of Lung Diseases of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Data were downloaded from the NCBI database of genotypes and phenotypes (accession number phs000335.v2.p2)

Sources of funding: This project was partially funded by the NIH grants R01 HL094786 and R01 HL072966 from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, the Long-Range Research Initiative of the American Chemistry Council, and the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest. PJR is a Charter Member of a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Sunovian Pharmaceuticals, Inc., in Fort Lee, New Jersey. Sunovian is a pharmaceutical and drug development company.

Data and code availability/code: Data for the analyses conducted here can be downloaded from the database for genotypes and phenotypes (dbGaP). The code for conducting analyses is available from the online electronic appendix.

References

- 1.Schildcrout JS, Heagerty PJ. On outcome-dependent sampling designs for longitudinal binary response data with time-varying covariates. Biostatistics. 2008 Oct;9:735–749. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxn006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schildcrout JS, Heagerty PJ. Outcome-dependent sampling from existing cohorts with longitudinal binary response data: study planning and analysis. Biometrics. 2011 Dec;67:1583–1593. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2011.01582.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schildcrout JS, Rathouz PJ, Zelnick LR, Garbett SP, Heagerty PJ. Biased sampling designs to improve research efficiency: factors influencing pulmonary function over time in children with asthma. Ann Appl Stat. 2015 Jun;9:731–753. doi: 10.1214/15-AOAS826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connett JE, Kusek JW, Bailey WC, O’Hara P, Wu M. Design of the Lung Health Study: a randomized clinical trial of early intervention for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Control Clin Trials. 1993 Apr;14:3S–19S. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(93)90021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anthonisen NR, Connett JE, Kiley JP, Altose MD, Bailey WC, Buist AS, Conway WA, Enright PL, Kanner RE, O’Hara P. Effects of smoking intervention and the use of an inhaled anticholinergic bronchodilator on the rate of decline of FEV1. The Lung Health Study. JAMA. 1994 Nov;272:1497–1505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanner RE, Connett JE, Williams DE, Buist AS. Effects of randomized assignment to a smoking cessation intervention and changes in smoking habits on respiratory symptoms in smokers with early chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the Lung Health Study. Am J Med. 1999 Apr;106:410–416. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00056-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JH, Cho MH, Hersh CP, McDonald ML, Crapo JD, Bakke PS, Gulsvik A, Comellas AP, Wendt CH, Lomas DA, Kim V, Silverman EK. Genetic susceptibility for chronic bronchitis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res. 2014;15:113. doi: 10.1186/s12931-014-0113-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mailman MD, Feolo M, Jin Y, Kimura M, Tryka K, Bagoutdinov R, Hao L, Kiang A, Paschall J, Phan L, et al. The ncbi dbgap database of genotypes and phenotypes. Nature genetics. 2007;39(10):1181–1186. doi: 10.1038/ng1007-1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franklin JM, Schneeweiss S, Polinski JM, Rassen JA. Plasmode simulation for the evaluation of pharmacoepidemiologic methods in complex healthcare databases. Computational statistics & data analysis. 2014;72:219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.csda.2013.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neuhaus JM, Kalbfleisch JD. Between- and within-cluster covariate effects in the analysis of clustered data. Biometrics. 1998 Jun;54:638–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goetgeluk S, Vansteelandt S. Conditional generalized estimating equations for the analysis of clustered and longitudinal data. Biometrics. 2008 Sep;64:772–780. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brumback BA, Dailey AB, Brumback LC, Livingston MD, He Z. Adjusting for confounding by cluster using generalized linear mixed models. Statistics & Probability Letters. 2010 Nov 1;80:1650–1654. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neuhaus JM, McCulloch CE. Separating between- and within-cluster covariate effects by using conditional and partitioning methods. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B-Statistical Methodology. 2006;68(5):859–872. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brumback BA, Li L, Cai Z. On the use of between-within models to adjust for confounding due to unmeasured cluster-level covariates. Communications in Statistics - Simulation and Computation. 2017;46(5):3841–3854. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frisell T, Oberg S, Kuja-Halkola ¨R, Sjölander A. Sibling comparison designs: bias from non-shared confounders and measurement error. Epidemiology. 2012;23(5):713–720. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31825fa230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sjölander A, Frisell T, Öberg SA. Causal interpretations of between-within models for twin research. Epidemiologic Methods. 2012;1(1):217. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azzalini A. Logistic regression for autocorrelated data with application to repeated measures (Corr: 97V84 p989) Biometrika. 1994;81:767–775. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heagerty PJ. Marginally specified logistic-normal models for longitudinal binary data. Biometrics. 1999;55(3):688–698. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heagerty PJ. Marginalized transition models and likelihood inference for longitudinal categorical data. Biometrics. 2002;58(2):342–351. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2002.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stiratelli R, Laird N, Ware JH. Random-effects models for serial observations with binary response. Biometrics. 1984 Dec;40:961–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breslow NE, Clayton DG. Approximate inference in generalized linear mixed models. Journal of the American statistical Association. 1993;88(421):9–25. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986 Mar;42:121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schildcrout JS, Heagerty PJ. Marginalized models for moderate to long series of longitudinal binary response data. Biometrics. 2007 Jun;63:322–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2006.00680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heagerty PJ, Zeger SL. Marginalized multilevel models and likelihood inference (with comments and a rejoinder by the authors) Statistical Science. 2000;15(1):1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horvitz DG, Thompson DJ. A generalization of sampling without replacement from a finite universe. Journal of the American statistical Association. 1952;47(260):663–685. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robins JM, Rotnitzky A, Zhao LP. Estimation of regression coefficients when some regressors are not always observed. Journal of the American statistical Association. 1994;89(427):846–866. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubin DB. Inference and missing data. Biometrika. 1976;63(3):581–592. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. John Wiley & Sons; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neuhaus JM, Lesperance ML. Estimation efficiency in a binary mixed-effects model setting. Biometrika. 1996;83(2):441–446. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sjölander A, Johansson AL, Lundholm C, Altman D, Almqvist C, Pawitan Y, et al. Analysis of 1: 1 matched cohort studies and twin studies, with binary exposures and binary outcomes. Statistical Science. 2012;27(3):395–411. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Breslow NE, Chatterjee N. Design and analysis of two-phase studies with binary outcome applied to Wilms tumour prognosis. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series C: Applied Statistics. 1999;48:457–468. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scott AJ, Wild CJ. Fitting logistic models under case-control or choice based sampling. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B: Methodological. 1986;48:170–182. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xie Y, Manski CF. The logit model and response-based samples. Sociological Methods & Research. 1989;17(3):283–302. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hernán MÁ, Brumback B, Robins JM. Marginal structural models to estimate the causal effect of zidovudine on the survival of hiv-positive men. Epidemiology. 2000;11(5):561–570. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robins JM, Hernan MA, Brumback B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2000 Sep;11:550–560. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.