Abstract

Intimate partner violence (IPV) may increase as women in patriarchal societies become empowered, implicitly or explicitly challenging prevailing gender norms. Prior evidence suggests an inverse U-shaped relationship between women’s empowerment and IPV, in which violence against women first increases and then decreases as more egalitarian gender norms gradually gain acceptance. By means of focus group discussions and in-depth interviews with men in 10 Bangladeshi villages, this study explores men’s evolving views of women, gender norms and the legitimacy of men’s perpetration of IPV in the context of a gender transition. It examines men’s often-contradictory narratives about women’s empowerment and concomitant changes in norms of masculinity, and identifies aspects of women’s empowerment that are most likely to provoke a male backlash. The findings suggest that men’s growing acceptance of egalitarian gender norms and their self-reported decreased engagement in IPV are driven largely by pragmatic self-interest: their desire to improve their economic status and fear of negative consequences of IPV.

Keywords: Intimate Partner Violence, Empowerment, Masculinity, Qualitative

Introduction

Evidence from various settings worldwide links men’s violence against their intimate partners with systems of gender inequality and hegemonic masculinity (Solotaroff and Pande 2014; Jewkes 2002). There is widespread recognition that intimate partner violence (IPV) cannot be understood in any meaningful or useful way without understanding how masculinities are constructed, and how they function (e.g., DeKeseredy and Schwartz [2005]). Common features of systems of masculine hegemony, or patriarchy, are the social construction of men as superior to women, as women’s providers and protectors, responsible for ensuring their welfare and guarding their sexuality, and of IPV as an aspect of masculinity and a legitimate means for men to control and instruct women. Usually it is the threat of violence more than its actual use that maintains men’s power within their families (Goode 1971). And almost always, in such systems, women as well as men condone IPV, illustrating Gramsci’s (1971) insight that power usually rests on relative consensus rather than routine use of force.

Masculine norms are inextricably linked with, and often articulated in opposition to, feminine norms, and typically express and justify women’s subordination to men (Scott 1988; Connell 1995; Jewkes, Levine and Penn-Kekana 2015). When feminine norms evolve (e.g., in response to expanded educational and employment opportunities for girls and women, and laws and policies supporting women’s equal rights and social participation), masculine norms may evolve to accommodate greater gender equity, or they may be thrown into crisis. In the former case, men may establish more collaborative, companionate and collegial relationships with their wives, help with housework, and/or change their routines to accommodate their wives’ income-generating activities (Schuler et al. 2013). Alternatively, men may draw upon existing paradigms of hegemonic masculinity, view women’s empowerment—their acquisition of resources, agency and ability to make strategic life choices in the context of gender inequality (Malhotra and Schuler 2005)—as transgressive of social norms, feel that their masculine identities are being challenged, and respond with hostility and violence. Thus, studies have found women and girls perceived to be transgressing patriarchal gender roles to be at greater risk of sexual violence (Kelly-Hanku et al. 2016). The interaction of hegemonic masculine ideals with other common IPV risk factors (such as poverty, low education, depression or misuse of alcohol or drugs) can make it more difficult for men to achieve ideal norms of masculinity, undermining men’s gender identities and their sense of control and dominance, and exacerbating the risk of IPV perpetration (Jewkes, Flood, and Lang 2015, Peralta and Tuttle 2013).

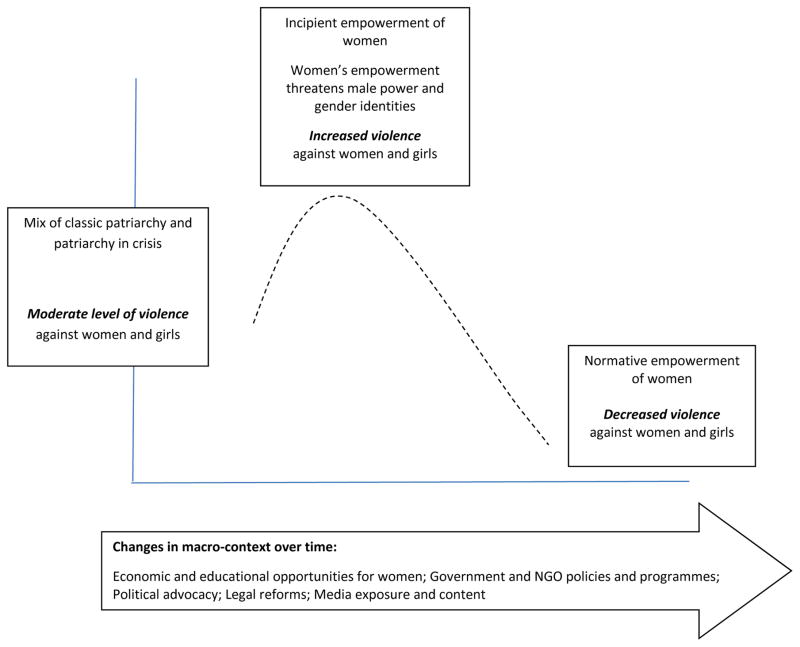

As Jewkes et al. (2002) found with the relationship between IPV and female education, we theorize that in societies where gender transitions and women’s empowerment are occurring, the prevalence of IPV follows an inverse U-shaped curve. IPV first increases and then decreases as women’s empowerment shifts from incipient to normative (Figure 1). Early in the transition to greater gender equality, empowered women are perceived as transgressing gender norms, thus challenging masculine hegemony. Eventually gender norms change to accommodate a more equitable social reality.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized effect of evolving gender norms on the prevalence of intimate partner violence over time

Historically, Bangladeshi women have been vulnerable to violence primarily because of their lack of empowerment, including both economic dimensions such as earning a cash income and controlling money (leaving them dependent on marriage for access to resources), and social dimensions such as knowledge of the laws and legal system, social support, and access to telephones and media (Hashemi, Schuler, and Riley 1996; Schuler, Hashemi, and Badal 1998). Household poverty contributes to IPV, as poverty causes stress and threatens men’s status as providers. As Cain, Khanam and Nahar (1979) and later Kandiyoti (1988) have described, in the early decades after Bangladesh’s independence (1971), extreme poverty led to a crisis in the prevailing patriarchal system. Men often found it difficult or impossible to fulfil their end of what Kandiyoti refers to as the ‘patriarchal bargain’, in which norms dictate that a man must provide material support for his wife and family. Seeing no more empowering alternatives, women often responded by pressuring their husbands to live up to their patriarchal obligations. A study by Schuler, Hashemi, and Badal (1998) in the early 1990s found that such pressure was one of the most frequent triggers of IPV. Ironically, as more opportunities opened for women in Bangladesh and rural women gradually became more economically active, this too was often met with IPV. As depicted in Figure 1, although an empowered woman’s economic contributions may help to alleviate household poverty, her empowerment may also trigger IPV (Amin et al. 2013; Bates et al. 2004; Naved and Persson 2005) because her husband’s power and identity is challenged (Bates et al. 2004).

We would expect to find a mix of male responses to women’s empowerment in settings where gender norms are in transition. This qualitative study was undertaken during such a transition, when rates of IPV in Bangladesh were still very high, but recent evidence from surveys had begun to suggest the beginning of a decline. In nationally representative samples, the proportion of ever married rural women reporting they had experienced physical or sexual IPV from the time of marriage dropped from 57.8% to 54.2% between 2011 and 2015 and the proportion who said they had experienced this in the prior year decreased from 37.0% to 26.9% (BBS 2013, 2015). Here we use focus groups and in-depth interviews with men to analyze competing narratives about women, masculinities and IPV, and attempt to better understand men’s responses to women’s empowerment and the evolving relationship between women’s empowerment and IPV. We also unpack the concept of women’s empowerment in analyzing which manifestations tend to elicit hostility and which men are more apt to appreciate at this stage in the evolution of gender norms.

Methods

This study is part of a five year, mixed methods research project examining relationships between women’s empowerment and IPV in the context of evolving gender norms. The parent study seeks to clarify the individual and community-level mechanisms by which women’s empowerment is associated with the risk of IPV. The qualitative component explores the social dynamics and processes underlying these relationships. The study was reviewed for ethical compliance and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of FHI 360 and BRAC University.

Research sites

The qualitative study took place in 10 villages located in seven districts of rural Bangladesh. The villages differ in the way they were selected. Six of them are longstanding sites where members of the research team had been conducting research for more than two decades. They were chosen in 1991 based on the presence/absence, and duration of operation, of two prominent Bangladeshi microcredit programs. Two groups of three villages each were located in two parts of the country where no social research had been done or was underway. The other four villages were selected from a nationally representative sample of 78 communities where surveys were conducted in 2013 and 2014 as part of the present study. To maximize variation, we used the 2013 survey data to identify four communities with high or low levels of IPV and women’s empowerment among recently married women. Our index of empowerment included eight dichotomous indicators described in a previous study of rural credit programs in Bangladesh (Hashemi, Schuler, and Riley 1996), each tapping a separate dimension of empowerment (mobility, involvement in family decisions, economic security, etc.). We categorized the villages into four cells and selected a village from each cell that was far from the mean on both variables (Table 1).

Table 1.

Village-level mean past-year physical IPV prevalence and empowerment scores among married women in sampled villages, 2013*

| Empowerment score** | ||

|---|---|---|

| Past year IPV % | High | Low |

| High | Village 8: 51% / .28 | Village 7: 65% / −.14 |

| Low | Village 9: 15% / .42 | Village 10: 21% / −.43 |

From Schuler et al. 2016.

Village-level range: −.66 to +.43

In the context of Bangladesh, none of the 10 villages or the districts in which they are located was particularly atypical. The inhabitants were predominantly Sunni Muslim, with small Hindu enclaves in two villages. The majority of households in each village was poor. Some villages were poorer than others, but unlike 10–15 years previously, virtually no one in any of the villages was destitute. Most families had access to television, which some owned and others watched in tea stalls, shops or neighbouring homes. The majority of families had at least one mobile phone. As in most of the country, in all 10 villages both government and religious schools (madrasas) were easily accessible and several NGOs were active, offering services such as micro-finance, skills training, primary health care, education, and legal information and support. Sources of employment for women included garment factories near two villages, a jute mill in one, various construction projects, weeding of rice paddies, harvesting, tailoring, poultry-raising, livestock rearing, teaching, private tutoring, and employment by the NGOs themselves. Substantial numbers of men and women from some villages had migrated to Dhaka, where the men worked in occupations such as rickshaw pulling or construction, or in garment factories, and the women worked in garment factories or as domestic servants. A few men from each village were working in the Middle East.

Data and procedures

Between 2011 and 2014, we conducted 21 focus group discussions (FGD), 1–2 hours in duration, with groups of 4–8 men, and 39 in-depth interviews (IDIs), about an hour in duration, with individual men (Table 2).

Table 2.

Numbers of in-depth interviews and focus group discussions with men by village, 2013

| Village | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #IDIs | 4 | 4 | 1 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 39 |

| #FGDs | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 21 |

| Total | 6 | 5 | 5 | 13 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 60 |

We conducted a mapping exercise in each village to understand its economic base and resources, social structure, access to transportation links, presence of NGOs, and demographic features such as labour migration. Within sites, the men were chosen based on availability and efforts to spread the interviews among men from various sections of the village. A limitation of the study is that both the IDI and the FGD samples are somewhat biased toward older men. Most younger men were out working most of the day, frequenting tea stalls or other gathering places in the evenings. We avoided interviewing men from the most affluent households, except as key informants in conjunction with village mapping, because they were relatively few. An interview guide was used, and additional topics emerged from the discussions. In the FGDs the men were asked to talk about the situation in their communities, and in doing so they typically revealed their own attitudes. In the IDIs they were asked more directly about their own perceptions and attitudes. Even though they were not specifically asked, men often spoke about broader changes, both regional and national. The sensitivity of the topic generally constitutes a limitation in studies of IPV. However, its commonness and its social acceptance in this particular setting probably makes it less sensitive here than in settings where it is less prevalent. One might have expected men in FGDs to be less forthcoming on the subject than men interviewed individually, but we did not find this to be the case. In neither type of interview did we ask men about their own status as perpetrators of IPV.

The interviewers were two Bangladeshi men, one with long experience conducting qualitative research in six of these villages who was well known by, and friendly with, the inhabitants. His younger partner found it easy to establish rapport because of his association with a researcher who was known and trusted. The interviews were conducted in the local language, Bangla, audio-recorded, transcribed and translated into English in Dhaka by professional translators and or by the senior field researcher. The senior field researcher (one of the authors [S.H.B.]) checked the English versions for completeness and accuracy. Field notes provided additional detail.

Analysis

The authors analysed the data thematically, reading entire transcripts along with field notes to identify and juxtapose salient themes in their narrative contexts. The transcripts were also coded in NVivo 10 by two analysts to assemble and evaluate supporting evidence and counterevidence to test and revise initial interpretations of the lead author. Discrepancies were resolved through face-to-face discussions of alternative interpretations. We conducted analyses of inter-coder agreement at intervals to ensure the codes were applied consistently. The field research team reviewed the findings and conclusions and discussed them with the lead author, who further revised them. Results were also triangulated with findings from 13 focus groups and 74 life history narratives with women from the same villages (findings reported in Schuler et al. 2013, 2016).

Findings

The 12-month prevalence of IPV varied widely among the 10 villages, from as little as 15% to as much as 59%. Notwithstanding these variations, in virtually every village the IDIs and FGDs with men revealed mixed enthusiasm, ambivalence and resentment regarding women’s empowerment. (Rather than the term ‘empowerment’ we used colloquial terms—e.g., we asked how women’s behaviour had changed in recent years, or compared with a generation ago, and whether these changes were seen as good or bad.) Overall, the interviews convey a sense that women’s empowerment has destabilised the men’s understandings of masculinity and femininity. Their explanations of the gender transition in which they find themselves in some contexts express acceptance and in others suggest backlash. Both men’s enthusiasm and their resentment focus on specific dimensions of empowerment.

Women’s empowerment as described by men

In all villages, men described improvements in female education and changes in women’s work and economic contribution, explaining them as consequences of broader changes such as intensification of agriculture, development of rural industries, male labour migration, and governmental and NGO initiatives such as educational stipends, skills training, job creation, and provision of microloans and assets such as poultry and livestock to women. They often said that poverty had decreased in their villages, explaining this both as a result of broader economic developments and, more specifically, women’s economic contributions.

As illustrated in the following sections, the men also commented on girls’ and women’s increased mobility and presence in the public domain in conjunction with school, work outside the home, shopping, and visits to relatives or friends. They mentioned related changes in women’s natures, describing them as more worldly, politically aware, knowledgeable about family law, confident, competent, articulate, shrewd, and sometimes as immodest, imperious, demanding, disrespectful or argumentative.

Positive perceptions of women’s empowerment

Positive statements about women’s empowerment focused on three themes: the value of women’s income or skills in household management, reducing household poverty, the benefit of an educated wife in supporting children’s education, and the improved language and comportment of educated women. When men described the impact of women’s income in improving the lives of poor families, they often linked this with women’s increased mobility.

Now women are joining the society, going here and there. In the past, women never got out of the house. But in the past, people starved to death too. Now no one is starving to death. (FGD, Village 8, age 40, 10 years education)

Many men said that women working from home was preferable to avoid loss of status, though it was by no means clear that, if an opportunity arose, they would have prevented their wives from working in public.

In addition to working for income, men noted that women skilled in household management help their families economically and that educated women educate their children. Many men appreciated that today’s women kept their houses, children, and themselves in better, more hygienic conditions and practiced family planning. Many also said women’s manners had improved.

They now greet seniors when they meet them on the streets and enquire about health and wellbeing. Women’s language, choice of words, manner of speaking all have changed. They used to use insolent terms of address. (IDI, Village 2, age 55, 5 years education)

Negative perceptions of women’s empowerment

Emergent aspects of women’s empowerment that men most often characterised as transgressive and described in negative, derogatory or resentful ways were their presence in the public sphere (particularly in markets, previously off-limits); controlling, disrespecting, defying or arguing with husbands; and, more abstractly, going against the natural order of things by being superior or in control. Negative statements about women’s increased presence in public emphasized two aspects of this: 1) going against purdah norms, seen as grounded in religion, in their dress, comportment or mere presence in public; and 2) inconveniencing or disrespecting men by their comportment or presence in public. The quotes below are typical.

They are not following our commands, our directives, in any way! (FGD, Village 6, age 37, 8 years education)

Because of women, we can’t walk properly on the road. They don’t walk along the side of the road [as they used to]. They take the middle of the road when they walk. (FGD, Village 10, age 40, 10 years education)

There’s no room for men in the markets as they are jam-packed with women. (FGD, Village 10, age 54, 10 years education)

The implication is that it is natural and proper for men, not women, to walk in the middle of the road. Crowds are quite normal in Bangladesh, and people rarely complain of them (except for urban residents who face traffic jams). What seems to make the crowds described here objectionable to men is that they include women. Men also characterized women’s presence in public as a symptom of social deterioration and deviation from religious laws. Below, women’s presence in public is described as ‘unruly’. This quote comes from the village with the highest rate of violence.

These changes have not been positive for the society. Women should not move about in such unruly ways.… We live our life according to Sharia (Islamic law), and if we are to abide by that law then it is wrong for women to frequent markets and other places. But the society that once abided by that law doesn’t exist anymore. (IDI, Village 7, age 53, no education)

As with women walking down the middle of the road, the man quoted below characterizes women’s increased mobility as a violation of the distinction between men and women. He also sees it as an affront to men’s honour, which is culturally linked with keeping women under control and out of sight. Note the use of the terms ‘at will’ and ‘open’.

Women now consider themselves like men. The time we now live in sees many women move about freely and go to the market at will. This going to the market has made them open. Their transformation has turned things worse. Women from every home, even my aunt and sister, go to the market leaving men behind at home. Men in fact do not have the honour they had in the past. (FGD, Village 6, age 26, 5 years education)

Men remarked that women’s dress styles had become too tight and revealing (even though, in the past, many men could not afford sari blouses and petticoats for their wives, making it difficult for the women to avoid occasionally exposing their breasts or legs while working out of doors—e.g., husking and drying paddy, fetching water). Some commented that the burqa had become a fashion item, no longer designed to conceal the female figure. Men also described women as aggressive and quarrelsome. They saw this as a result of their earning an income (a dimension of empowerment men praised in other contexts).

Today’s women have become chora (shrill)….women couldn’t earn money in the past, so they were a little timid back then. (IDI, Village 7, age 53, no education)

Some of the men distinguished social empowerment or knowledge of the outside world as a source of malevolent power in women, in contrast to economic empowerment and education.

Brother, it is not because of work or earning that women challenge [men]…. There are some women who are like witches. These witch-like women are defiant… bad women you cannot convince or control…. They assert their opinion constantly. These women will always ask you to do whatever they want. They engage in quarrels without any purpose…. And now they are aware of so many things. They get information in different ways; they come to know things from the NGOs, from health workers and others. All these things they come to know, and they become more unwavering. They know about rules and laws and feel more powerful. They use their knowledge and power unlawfully…. This is how they control men. (IDI, Village 2, age 56, 10 years education)

As illustrated in the quotes above, men seem very concerned with symbolic aspects of increased gender equality. While they do not name it as such, clearly they feel that patriarchy is endangered. When men say women use knowledge and power unlawfully, they are not referring to the country’s legal statutes but, rather, to the ‘law’ of patriarchy. Women are construed as witches exercising capricious, unreasonable, unnatural and illegitimate power. Women are described as shrill, opinionated, out of control and, worse, as controlling men.

In addition to the NGOs and health workers mentioned above, men cited TV dramas and mobile phones as negative influences, implying that exposure to knowledge (e.g., about rights and the law) and alternative lifestyles, as well as contact with others, were undermining social norms, instigating women to dishonour men and, by extension, weakening the system of masculine hegemony.

Justifications of changing gender norms

In all 10 communities, working women’s, and to a lesser extent men’s, deviations from traditional gender norms were justified on economic grounds. The following quote comes from the village with the highest rate of past year IPV (59%):

Interviewer: Why don’t people in the community (say) something to humiliate him, why don’t they criticize him because his wife earns income and he enjoys her money?

Participant: Because people can see that his wife’s efforts have been helpful in running the family smoothly and that things are going well. Now they say, ‘Well, at least his wife is earning income. She makes good money. His family is prospering--May he prosper!’ Those who couldn’t get one square meal a day don’t have problem of food anymore. (IDI, Village 7, age 53, no education)

The vast majority of study participants said husbands now help their wives with at least some of the household chores, particularly if the woman works outside the home and/or they do not live in a joint family. They rationalized this in various ways.

Before, society would make negative comments about [men who help wives with household work]. They were called ‘muggi purush’ (a derogatory term describing a man with a feminine nature)…. Everyone now tends to think: if I help her out it will benefit both of us. (IDI, Village 1, age 32, 8 years education)

Men sometimes described women’s and girls’ current dress styles as intentionally provocative. In other cases they justified abandonment of traditional dress on grounds of practical necessity:

Now a girl needs to ride a bicycle to get to work or college…. How could she put on a burqa? If a girl works for BRAC (a large NGO) she will have to ride a bicycle. She cannot do this while being a big devotee to purdah. Her scarf will get tangled in the bicycle wheels. (FGD Village 6, age 42, 10 years education)

In all villages, men referred to gender equality/women’s rights (shoman adhikar, meyeder adhikar, betider adhikar) only in a mocking, complaining sense, but they sometimes rationalized gender equality and alluded to women’s rights using other words. The distinction suggests that men may have been resistant to symbolic aspects of greater gender equality (viewing it as a threat to their status and value as men) but were often ready to accept it insofar as it brought them practical advantages (increased household income, a lighter burden of responsibility).

Men were sometimes creative in rationalizing deviations from traditional patriarchal gender norms, which they tended to see as religiously grounded:

Poorer people will not be able to survive if they observe purdah in a khas (genuine/proper/true/orthodox) sense. For the sake of their work, they [women] have to talk to so many men.…Brother, in the current age it is not possible to abide by all those things. According to religious interpretations, we are the creatures of the final age; we are prophet’s last generation of followers; we are nearing the end of everything. Living in this age, we can follow only one tenth of the religious rulings. If we can do that at least, Allah the almighty will pardon us. (IDI, Village 2, age 56, 10 years education)

Some of the men insisted that women’s greater economic and social participation was possible only because their husbands permitted it, that men’s power was not declining, while other statements suggested otherwise. In their often-contradictory narratives, men are responding to the gender transition in which they find themselves sometimes by characterizing emerging definitions of masculinity and femininity as normal and rational, and at other times denying or demeaning them.

In some cases it happens like that--a man loses his power and control and people start to say things about him: that the man has no power or capacity, no vigour, he cannot guide his wife, he is worth nothing, and so on... (IDI, Village 2, age 56, 10 years education)

Men’s perspectives on the promotion of gender equity

Quite a few men complained that the government excessively promoted women’s empowerment, such that men and boys were now unfairly disadvantaged, particularly in access to employment. Some implied that government policies spoiled women and humiliated men. In the quotes below, men link their resentment of changing gender norms in the private sphere to developments in the public sphere, elevating their feelings of insecurity and humiliation to the political level. In their perception, the allocation even of private sector economic opportunities and prestige is a zero-sum game controlled by the government. (Never mind that traditional society was ridden by corruption and controlled by a privileged few.)

The government has established equal rights for women. For example, if you send 10 men and 20 women for a job in a garment factory, all 20 of those girls will get a job but none of the 10 boys will…. If things were like before, I mean if the government hadn’t facilitated so many job opportunities for women, then they would still have to follow their husbands’ wishes. Today’s women don’t follow these rules. They think they have equal rights and so they go here and there and live their lives as they wish. (FGD, Village 9)

…

FGD participant 1: The government of Bangladesh has given more power to women. [Let’s say] I am SSC (secondary school certificate) passed and so is my wife, but I don’t get a job while my wife does and I end up living the life of a servile [person]. I have to prepare food for my family and look after my children as my wife has to go to the office at 9 in the morning. She will teach students and return home at 4 in the afternoon. She wakes up in the morning and takes care of a few chores—what else can I ask her to do now? After all, I am her servant. And if the need arises, I will have to cook and wash clothes too. She may take a shower and leave her clothes out. What else can I do but wash those clothes? (age 40, 10 years education)

FGD participant 4: This is your failure. You are a…(age 54, 10 years education)

FGD participant 1: Will you give me a break? Suppose she returns at 5 in the afternoon. She will be taking her lunch then. But I had to cook and do everything else at home. Who is making me do all this? The Bangladesh Government is making me do all this! It has brought upon us such humiliation and disgrace!…So we must treat them as our superiors. And why? Because the head of our government is a woman!

FGD participant 2: If we had two leaders such as Sheikh Mujib or Ziaur Rahman (male leaders around the time of the country’s independence) we could roar out like women have and asserted our authority in our families, but we can’t do that—how can we do that?! They have been given the key to rule and now we have to ask them even if we need two taka (less than a penny). (age 37, 10 years education)—FGD, Village 10

Perceived links between empowerment and IPV

Men in all ten villages said that both the frequency and the severity of IPV had decreased. A recent census with currently married women in six of the villages confirmed that the percentage experiencing IPV in the prior 12 months had dropped from about 36% to 25% between 2002 and 2014. When men were asked why they thought violence had decreased, answers varied, but many of the men said husbands and wives had fewer arguments because household poverty had decreased. Men often implied and sometimes directly stated that this decrease in poverty—and in IPV—was due to women’s augmented roles in income generation through their own earnings or their management of household resources. Men also mentioned laws against violence against women and women’s increased access to legal recourse as strong deterrents to violence. Men perceived women as better able, and more likely, to leave their husbands because of women’s increased ability to support themselves and because of their improved access to recourse.

Years back many men would beat their wives. Now this beating has decreased. Suppose my wife does earth digging work or work in the fields. If I beat her she will not stay here, will simply leave me. She will depart. Among the poor, men fear losing their wives. I am a weak person. I can’t run my family alone. Together with my wife, we run our family. She won’t live with me if I beat her. (IDI, Village 9, age 61, no education)

…

FGD participant 5: Well, government has endowed women with a certain power. These things are broadcast on TV. If a woman complains to the police against her husband, they will come and arrest him and put him in jail. The police will not care what you have to say, they will only listen to the woman. Fearing this, men do not want to get into trouble with their wives…. Besides, women know every place now. In the past they did not know how to go anywhere, did not know anything. But today’s women are not like that. They know everything, from the courthouse to anything you may mention. If you hit your wife, she is not going to put up with it. She will go to the police station and file a case against you…. There are many examples. Many women have filed cases against their husbands. (age 40, no education)

FGD participant 2: Many NGOs inform women about laws and [recourse mechanisms]. You know, there are many NGOs in the villages. People come from Dhaka to teach women things. They teach them about their rights, a husband’s duty to his wife. They also help women file cases against their husbands. Do you know the case of ‘violence against women’?…Everyone has a TV in their house. Everyone has cable connection. Everyone watches TV. Women learn many things by watching TV programs. They know many tricks. They are aware of their rights. And that’s where they get ideas about how to live their lives. (FGD, Village 5, age 38, 12 years education)

In the statements above, the idea that government has played a major role in destabilizing gender norms recurs, as does the idea that knowledge confers power. The juxtaposition of the words ‘tricks’ and ‘rights’ above highlights the men’s ambivalence about women’s empowerment. The quotes also reveal men’s perception that IPV is no longer a viable option for men when women become empowered.

Discussion

This study illustrates the unevenness of social change and the often-contradictory ideation that may arise as social actors attempt to make sense of and come to terms with their changing reality. Even two decades ago, when we began our research project in rural Bangladesh, people excused destitute women from complying with purdah norms, rationalizing their behavior on the grounds that they survived only by going out to work (Schuler, Islam, and Rottach 2010). Now, despite substantial reductions in rural poverty, a growing segment of women is widely considered to be exempt from these norms. With a few exceptions, men in this study praised women who worked outside their homes. Yet questions about how women today compared with previous generations evoked statements that women had lost their sense of propriety and their respect for men, and had become immodest, imperious egoists.

Curiously, when men expressed resentment over government policies promoting women’s empowerment and described their negative impact on gender relations, they rarely spoke about their own situations. This may be in part because they were asked to comment on changes in their communities, but the interviews also convey a sense that some of the men were expressing fears and perceived threats based on collectively generated stereotypes rather than personal experience. Life history narratives with young women from the same communities (Schuler et al. 2016) virtually never revealed levels of audacity, freedom and imperiousness among women that the interviews with men suggested. And women from these communities with salaried jobs were far fewer than the men implied.

What men disliked about women’s empowerment was more symbolic than pragmatic. They felt their hegemony and their natural superiority as men were being challenged. They exaggerated the extent that empowered women flouted social norms and saw this as an affront to men and a sign of malaise and disorder in society. Although relatively few women in these communities held salaried jobs, men perceived their government’s affirmative action policies as depriving them of jobs. They attributed this to the country’s female heads of state, even though some of these policies had been initiated under male prime ministers (Nazneen, Hossain, and Sultan 2011). The term ‘gender equality’ appeared to function as a lightning rod for men’s sense that their masculinity was being threatened.

In contrast, the men’s growing acceptance of egalitarian gender norms and their self-reported decreasing propensity to engage in IPV seem to have been driven largely by pragmatic considerations: their desire to improve their economic status through their wives’ labour and resource management, and fear of negative consequences if they engage in IPV. Social pressure and social aspirations influence the ways that men perceive their pragmatic interests, and may hasten or delay normative and behavioural changes.

Much of the theoretical literature as well as empirical studies on relationships between gender (or masculine) norms and IPV highlights the role of IPV in expressing and maintaining systems of ideation, institutions and social relations associated with men’s control over women and women’s sexuality (e.g., Connell [1995], McCarry [2007]). Our study goes further, in examining men’s responses to changing gender norms and various manifestations of women’s empowerment in a setting where a gender transition is taking place. Our work adds a sequel to Kandyoti’s (1988) description of the ‘patriarchal bargain’ in crisis several decades ago in rural Bangladesh when, because of widespread impoverishment, men often were unable to fulfil their traditional roles as providers. Seeing no better options, wives often did their best to adhere to their end of the bargain by remaining subservient and dependent, while pressuring their husbands to perform their roles as providers. (Although their husbands may not always have experienced this pressure as subservience.) Only when the family became desperate enough, and/or men died or deserted their families, did substantial numbers of women seek low-paid employment outside the home, and when they did they faced severe gender discrimination in the labour market.

As Kandiyoti (1988) posited, women’s strategies started to change as they began to see more empowering alternatives. The ‘patriarchal bargain’ has not ceased to exist in this setting, but its current configuration has become more nuanced and women now have more options. The male responses to women’s empowerment documented in this study suggest that there may be a ‘rough’ period followed by declining IPV as men gradually adjust to economic and social changes that ultimately benefit them but also entail greater gender equality.

Our findings are consistent with the hypothesis that, in the context of a gender transition, the relationship between women’s empowerment and IPV follows an inverse U-shaped trajectory, as empowerment becomes normative. The study also illustrates the ‘messiness’ in the process of normative change. It documents some of the ways that Bangladeshi men experience the ongoing transition toward greater gender equality, in which they themselves are active participants, illustrating how, in some contexts, ideation may ‘scramble’ to keep up with changing behaviour. The process through which men attempt to explain and rationalize what they do in pursuit of their pragmatic interests may be one of the ways that ideational change takes place. If this is the case, policy makers trying to promote nonviolent forms of masculinity should look carefully at what influences men’s pragmatic interests, and their perceptions thereof, in various transitional settings. Social and behavior change communication strategies would do well to draw on men’s own narratives of change.

If men’s resistance to women’s empowerment in this setting is largely a response to its symbolic meanings, should governments and NGOs avoid framing empowerment in terms of women’s rights or gender equality? Would men feel less threatened by language and imagery that appeals to their pragmatic self-interests and aspirations, such as juxtapositions of women’s work with accoutrements of family prosperity, women tutoring their children, or married couples having fun together? Greater investment in educational and job opportunities for boys and men as well as opportunities for girls and women also might help reduce men’s hostile responses to women’s empowerment. On the other hand, concepts of rights and equality are widely considered to be essential to women’s empowerment. By its very definition, empowerment entails an element of agency (Kabeer 1999). Merely offering opportunities for girls and women is insufficient; they need the inner resources, or sense of self-efficacy, to avail themselves of such opportunities. Exposure to ideas about rights and equality, especially in settings that promote solidarity among women, can help women and girls to find their inner resources (Kabeer 2011). We believe that it should be feasible to identify and emphasize men’s self-interests while continuing to advance concepts of social justice.

Findings from surveys in six of our 10 villages in 2002 and 2014, and qualitative findings from these villages, are consistent with the results of the national surveys mentioned earlier, which show a significant drop in prior-year IPV between 2011 and 2015. Insofar as these survey findings are robust, and if IPV continues to drop, rural Bangladesh may prove to be an important example of a setting in which masculine norms changed and IPV was reduced primarily as a result of economic improvements and interventions to empower women. As Flood (2015)2 points out, changing men does not always require working with men and can sometimes be achieved by empowering women. This may require structural changes in the legal system, law enforcement, and economic opportunities for women that decrease their dependence on men. In the case of rural Bangladesh, structural changes such as these, as well as direct interventions to empower women have proliferated, but examples of interventions to alter norms of masculinity are few. Still, it may be worth considering whether such changes could be accelerated through interventions with men to transform masculinities, particularly if attention is given to intersectionalities between hegemonic masculinity and structural factors that contribute to the economic marginalization of certain categories of men (Gibbs, Vaughan, and Aggleton 2015).

References

- Amin S, Khan TF, Rahman L, Naved Ruchira Tabassum. Mapping Violence against Women in Bangladesh: A Multilevel Analysis of Demographic and Health Survey Data. Dhaka: International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh; 2013. (icddr,b) [Google Scholar]

- BBS (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics) Report on Violence Against Women Survey 2011. Dhaka: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- BBS (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics) Report on Violence Against Women Survey 2015. Dhaka: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bates Lisa M, Schuler Sidney Ruth, Islam Farzana, Islam K. Socioeconomic Factors and Processes Associated with Domestic Violence in Rural Bangladesh. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2004;30(4):190–199. doi: 10.1363/3019004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain M, Khanam S, Nahar S. Class, Patriarchy, and the Structure of Women’s Work in Rural Bangladesh. Population and Development Review. 1979;5(3):405–438. [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW. Masculinities. Cambridge: Polity Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- DeKeseredy Walter S, Schwartz Martin D. Masculinities and Interpersonal Violence. In: Kimmel Michael S, Hearn J, Connell RW., editors. Handbook of Studies on Men and Masculinities. London: Sage; 2005. pp. 353–366. [Google Scholar]

- Flood Michael. Work with Men to End Violence Against Women: A Critical Stocktake. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2015;17(suppl2):159–176. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2015.1070435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs A, Vaughan C, Aggleton Peter. Beyong “Working with Men and Boys”: (Re)Defining, Challenging and Transforming Masculinities in Sexuality and Health Programmes and Policy. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2015;17(suppl2):85–95. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2015.1092260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode A. Force and Violence in the Family. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1971;33(4):624–636. [Google Scholar]

- Gramsci A. Selections from a Prison Notebook. London: Lawrence & Wishart; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi Syed M, Schuler Sidney Ruth, Riley Anne P. Rural Credit Programs and Women’s Empowerment in Bangladesh. World Development. 1996;24(4):635–653. [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes Rachel. Intimate Partner Violence: Causes and Prevention. The Lancet. 2002;359:1423–1429. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08357-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes Rachel, Flood Michael, Lang James. From Work with Men and Bys to Changes in Social Norms and Reduction of Inequities in Gender Relations: A Conceptual Shift in Prevention of Violence Against Women and Girls. Lancet. 2015;385:1580–1589. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61683-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes Rachel, Levin J, Penn-Kekana L. Risk Factors for Domestic Violence: Findings from a South African Cross-sectional Study. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55(9):1603–1617. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes Rachel, Morrell R, Hearn Jeff, Lundqvist E, Blackbeard D, Lindegger G, Quayle M, Sikweyiya Y, Gottzen L. Hegemonic Masculinity: Combining Theory and Practice in Gender Interventions. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2015;17(Suppl2):112–127. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2015.1085094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer N. Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment. Development and Change. 1999;30:435–464. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer Naila. Between Affiliation and Autonomy: Navigating Pathways of women’s Empowerment and Gender Justice in Rural Bangladesh. Development and Change. 2011;42(2):499–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7660.2011.01703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandiyoti D. Bargaining with Patriarchy. Gender & Society. 1988;2(3):274–290. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly-Hanku A, Aeno H, Wilson L, Eves R, Mek A, Trumb RN. Transgressive Women Don’t Deserve Protection: Young Men’s Narratives of Sexual Violence Against Women in Rural Papua New Guinea. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2016;18(11):1207–1220. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2016.1182216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra A, Schuler Sidney Ruth. Women’s Empowerment as a Variable in International Development. In: Naranyan Deepa., editor. Measuring Empowerment: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- McCarry Melanie. Masculinity Studies and Male Violence: Critique or Collusion? Women’s Studies International Forum. 2007;30:404–415. [Google Scholar]

- Naved Ruchira, Persson LA. Factors Associated with Spousal Physical Violence Against Women in Bangladesh. Studies in Family Planning. 2005;36(4):289–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2005.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazneen Sohela, Hossain Naomi, Sultan Maheen Sultan. IDS Working Paper. Brighton, UK: Institute for Development Studies; 2011. National Discourses on Women’s Empowerment in Bangladesh: Continuities and Change. [Google Scholar]

- Peralta Robert L, Tuttle Lori A. Male Perpetrators of Heterosexual-Partner-Violence: The Role of Threats to Masculinity. The Journal of Men’s Studies. 2013;21(3):255–276. [Google Scholar]

- Schuler Sidney, Lenzi Rachel, Badal Shamsul Huda, Bates Lisa. Women’s Empowerment as a Protective Factor Against Intimate Partner Violence in Bangladesh: A Qualitative Exploration of the Process and Limitations of Its Influence. Violence Against Women. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1077801216654576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler Sidney Ruth, Hashemi Syed M, Badal Shamsul Huda. Men’s Violence Against Women in Rural Bangladesh: Undermined or Exacerbated by Microcredit Programmes? Development in Practice. 1998;8(2):148–157. doi: 10.1080/09614529853774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler Sidney Ruth, Islam Farzana, Rottach Elisabeth. Women’s Empowerment Revisited: A Case Study from Bangladesh. Development in Practice. 2010;20(7):840–854. doi: 10.1080/09614524.2010.508108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler Sidney Ruth, Lenzi Rachel, Nazneen Sohela, Bates Lisa M. A Perceived Decline in Intimate Partner Violence Against Women in Bangladesh: Qualitative Evidence. Studies in Family Planning. 2013;44(3):243–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2013.00356.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott Joan W. Gender and Politics of History. New York: Columbia University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Solotaroff Jennifer L, Pande Rohini Prabha. Violence Against Women and girls: Lessons from South Asia. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2014. [Google Scholar]