Abstract

Objective

This study was conducted to examine the causal association between exercise and the risk of dementia among older Chinese adults.

Design

Longitudinal population-based study with a follow-up duration of 9 years.

Setting

Data for the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey waves occurring from 2002 to 2011–2012 were extracted from the survey database.

Participants

In total, 7501 dementia-free subjects who were older than 65 years were included at baseline. Dementia was defined as a self-reported or proxy-reported physician’s diagnosis of the disease.

Outcome measures and methods

Regular exercise and potential confounding variables were obtained via a self-report questionnaire. We generated longitudinal logistic regression models based on time-lagged generalised estimating equation to examine the causal association between exercise and dementia risk.

Results

Of the 7501 older Chinese people included in this study, 338 developed dementia during the 9-year follow-up period after excluding those who were lost to follow-up or deceased. People who regularly exercised had lower odds of developing dementia (OR=0.53, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.85) than those who did not exercise regularly.

Conclusion

Regular exercise was associated with decreased risk of dementia. Policy-makers should develop effective public health programmes and build exercise-friendly environments for the general public.

Keywords: dementia, exercise, GEE, older adults, China

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study was one of the first to examine the relationship between regular physical exercise and the odds of dementia among adults aged 65 years or older who were participating in a large 9-year prospective cohort study.

Longitudinal logistic regression models based on time-lagged generalised estimating equation were generated to make full use of the time-varying variables measured at each wave, thereby enabling us to obtain more reasonable and accurate results over the course of the 9-year study period.

The relationship between types, frequency, duration and intensity of exercise, and development of dementia was not examined because this information was not available in the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS) database.

Dementia was defined as a self-reported or proxy-reported physician’s diagnosis of the disease because these data were available in the CLHLS database, which may have led to potential biases.

Introduction

Dementia is a common irreversible geriatric disease and a major cause of morbidity and mortality among older adults. Dementia is characterised by the deterioration of memory, self-care, and quality of life. In the USA, the total cost of caring for a patient with dementia is approximately US$287 000, which is 57% higher than that of caring for a patient with any other disease.1 According to a recent report by the WHO, an estimated 47.5 million people are living with dementia worldwide, 90%–98% of whom are older than 65 years.2 China, the most populous country in the world, has a rapidly growing older population. According to the results of a meta-analysis published in 2010, this country is home to approximately 8.4 million people with dementia, and the direct costs associated with caring for these people exceeded US$17.5 billion.3 4

At present, there is no effective treatment available for dementia; thus, the high burden of dementia care emphasises the urgent need to conduct research on the prevention of dementia among older adults. Some population-based studies have suggested that exercise may lower the risk of dementia.5–7 For example, a cross-sectional study suggested that lower amount of physical activity could increase the risk of cognitive decline in older adults.5 A cohort study with 1740 participants aged 65 years or older found that regular exercise was associated with a delayed dementia development.6 Despite the evidence of the association between exercise and dementia onset, some studies have suggested otherwise.8 9 For instance, a 4-year prospective study with 6158 participants aged 65 years or older revealed that weekly exercise (mean hours=3.5) was not associated with the odds of Alzheimer’s disease (OR=1.04, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.10). The inconsistent conclusions of previous studies might have been due to the different sampling methods, measurements of exercise, study design and lengths of follow-up. In addition to these controversies, note that epidemiological studies examining the association between exercise and dementia have typically been cross-sectional or only controlled for baseline variables, and these data were treated as fixed information during the follow-up period,10–12 which may have led to potential biases; in fact, exercise status changes over time. In addition, data on the relationship between exercise and dementia based on the results of a longitudinal population survey conducted in China are scarce.

Accordingly, the current study, which was based on data from four waves of the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS) occurring from 2002 to 2011–2012, aimed to address the above literature gaps by examining the relationship between exercise and dementia risk among older Chinese adults using a time-lagged generalised estimating equation (GEE) model, which could make full use of time-varying variables information at each wave.

Methods

Data

Our data were derived from the CLHLS, an investigation conducted to understand the health status of older Chinese adults and the associated social, behavioural and biological factors; additionally, this first and largest longitudinal survey focused on the oldest-old in a low-income and middle-income country, and the data quality was believed to be generally acceptable.13 The CLHLS methodology has been described in detail elsewhere.14 Briefly, the baseline survey was launched in 1998, and the follow-up surveys were administered in 2000, 2002, 2005, 2008–2009 and 2011–2012. More than half of the counties and cities in 22 of the 31 provinces in China were selected to participate in the survey, representing approximately 85% of the Chinese population. The surveys, which were administered via face-to-face interviews, were used to collect data on family structure, marital status, activities of daily life (ADL), social activity, health status and lifestyle factors, including dementia and exercise, which were the focus of the current study. Duke University Health System’s Institutional Review Board members reviewed and approved this survey, and informed consent was obtained from each respondent.

Study sample

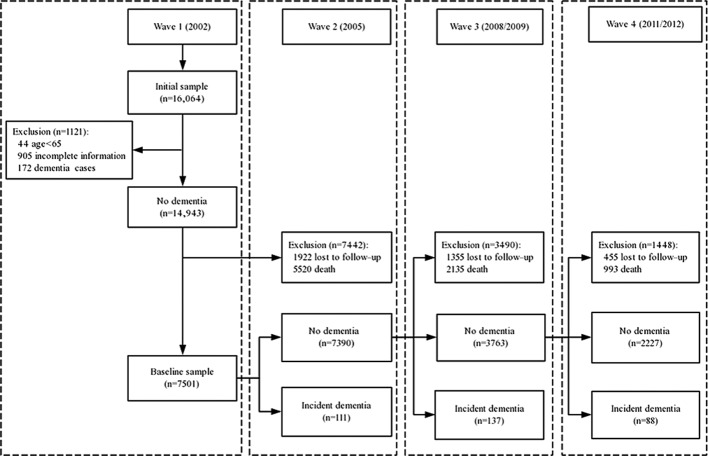

The 2002 wave was the first to include persons belonging to the young-old population (65–79 years); hence, this was the baseline wave in this analysis. The 2002 (wave 1) survey was administered to 16 064 participants. Those younger than the age of 65 years (n=44), those who did not have complete information on exercise and dementia (n=905), and those who had dementia at the baseline level (n=172) were excluded. Afterwards, 1922 individuals were excluded due to being lost to follow-up before wave 2. Additionally, dementia-free subjects who died before wave 2 (n=5520) were removed from this cohort, leaving 7501 participants in the follow-up sample. The screening procedure is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of sample selection.

Exercise and dementia

Regular exercise was measured using the question, ‘At present, do you regularly engage in exercise for fitness, such as walking, running, playing ball games, qi gong (a system of deep breathing exercise) or other exercise?’ In this study, housework and farm work were not classified as physical exercise. Participants were made aware of the difference between physical activity and physical exercise. Physical exercise was defined as planned, structured, repetitive activities performed with the objective of improving or maintaining physical fitness, while physical activity referred to any bodily movement, including occupational activities and housework.14

Questions used to assess dementia were based on self-reported or proxy-reported physicians’ diagnoses, including, ‘Are you suffering from dementia?’ and ‘Have you been diagnosed with dementia by a physician?’.15 Only those who answered ‘yes’ to both of the above questions were considered to have dementia. We also included those who suffered from dementia before death in this analysis.

Covariates

Based on the existing literature on dementia and exercise,6 16 the covariates included in the current study covered the following three domains: demographic characteristics, lifestyle factors and health status. Demographic characteristics included age group (grouped by every 10 years from 65 to 95 years of age), rural/urban residency, living alone, education level and main occupation before the age of 60 years. Lifestyle factors included current smoking, current drinking, engaging in regular organised social activities, gardening, playing cards/mah-jong or listening to radio/watching television. Health status included whether the participant had stroke or cerebrovascular disease, hypertension or diabetes. Their ADL was measured according to an adapted version scale of the Katz ADL Index and included eating, dressing, continence, toilet use, indoor transfer and bathing, and only those answering all the items as ‘completely independent’ were considered to be free of disability; all others were considered as having an ADL disability.

Statistical analyses

Frequency analyses and χ2 tests were used to describe the baseline characteristics and compare participants who exercised regularly with those who did not. At each occasion, exercise and confounders were lagged one wave relative to dementia outcome. Hence, data for exercise and confounders that had been collected at baseline (2002) from a dementia-free sample were used to predict the incidence of dementia at wave 2 (2005), and by analogy, exercise and confounders collected in the remaining dementia-free sample at wave 2 were used to predict the incidence of dementia at wave 3 (2008–2009); the same strategy was used for wave 3 and wave 4 (2011–2012). To make full use of the data from all four wave surveys, the causal association between exercise and the risk of dementia were evaluated by logistic regression models based on time-lagged GEE to address the issue of repeated measurements. We added the three sets of covariates in a stepwise manner. Model 1 included demographic characteristics, model 2 included the variables in model 1 plus lifestyle variables and model 3 included the variables in model 2 plus health status variables. Sixteen variables had missing values, and the missing proportion of variables ranged from 0.41% to 14.02%. The missing values were estimated by multiple imputation using the NORM software.17 All statistical analyses were performed using Stata V.13.0 (StataCorp).

Results

Baseline characteristics

As depicted in figure 1, 7501 participants were included at baseline, of whom, 338 (incidence rate 4.51%) developed dementia during the 9-year follow-up period, excluding those who were lost to follow-up or deceased, the death rate from 2002 to 2011–2012 was 53.84%. Table 1 depicts the baseline characteristics of participants by exercise status. All covariates, such as demographic characteristics, lifestyle factors and health status variables, were significantly associated with exercise. Exercise was significantly associated with younger age, male gender, higher education, non-farmer status and urban residency. People who lived not alone, smoked, drank, were more socially active, gardened, played cards/mah-jong or listened to radio/watched television were more likely to exercise. People with hypertension, diabetes and stroke or cerebrovascular disease were more likely to exercise.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics stratified by exercise status

| Variables | Exercise | P value* | Variables | Exercise | P value* | ||

| No (n=4644) |

Yes (n=2857) |

No (n=4644) |

Yes (n=2857) |

||||

| Dementia | 0.003 | Diabetes | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 4560 | 2830 | No | 4581 | 2782 | ||

| Yes | 84 | 27 | Yes | 63 | 75 | ||

| Age group (years) | <0.001 | Stroke or cerebrovascular disease | 0.016 | ||||

| 65~ | 1400 | 981 | No | 4474 | 2720 | ||

| 75~ | 1325 | 905 | Yes | 170 | 137 | ||

| 85~ | 1132 | 688 | ADL disability | <0.001 | |||

| 95~ | 787 | 283 | No | 3754 | 2521 | ||

| Gender | <0.001 | Yes | 890 | 336 | |||

| Male | 1818 | 1588 | Current smoker | 0.026 | |||

| Female | 2826 | 1269 | No | 3693 | 2210 | ||

| Residence | <0.001 | Yes | 951 | 647 | |||

| Urban | 1647 | 1707 | Current drinker | <0.001 | |||

| Rural | 2997 | 1150 | No | 3676 | 2103 | ||

| Living arrangement | <0.001 | Yes | 968 | 754 | |||

| Not alone | 3921 | 2535 | Social activity | <0.001 | |||

| Alone | 723 | 322 | No | 4390 | 2362 | ||

| Education | <0.001 | Yes | 254 | 495 | |||

| Illiteracy | 3029 | 1243 | Gardening | <0.001 | |||

| Primary | 1306 | 1050 | No | 4145 | 1960 | ||

| Postprimary | 309 | 564 | Yes | 499 | 897 | ||

| Occupation | <0.001 | Playing card/mah-jong | <0.001 | ||||

| Farmer | 3136 | 1245 | No | 3848 | 2048 | ||

| Non-farmer | 1508 | 1612 | Yes | 795 | 808 | ||

| Hypertension | 0.008 | Listening to radio/watching TV | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 4026 | 2414 | No | 1577 | 456 | ||

| Yes | 618 | 443 | Yes | 3067 | 2401 | ||

*P value for χ2 test.

ADL, activities of daily life; TV, television.

GEE analysis of the relationship of exercise and the risk of dementia

The results of the GEE analysis are presented in table 2. In all three models, exercise, age, residence and occupation remained significantly associated with dementia, even after adjusting for other variables. The OR for exercise increased from 0.42 (95% CI 0.26 to 0.67) to 0.53 (95% CI 0.33 to 0.85) when lifestyle and health status covariates were entered into the model. However, only one lifestyle factor, listening to radio/watching television, was significantly associated with decreased dementia risk. Furthermore, two of four health status variables, diabetes (OR=2.92, 95% CI 1.19 to 7.11) and ADL disability (OR=1.56, 95% CI 1.01 to 2.40), were significantly associated with dementia.

Table 2.

The causal association between exercise and the risk of dementia

| Variables | Model 1 | (95% CI) | Model 2 | (95% CI) | Model 3 | (95% CI) |

| Exercise | 0.42*** | (0.26 to 0.67) | 0.49** | (0.31 to 0.80) | 0.53** | (0.33 to 0.85) |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Age group (years) | 1.06*** | (1.04 to 1.07) | 1.05*** | (1.03 to 1.07) | 1.05*** | (1.02 to 1.07) |

| Gender (vs male) | 1.22 | (0.78 to 1.90) | 1.18 | (0.73 to 1.89) | 1.14 | (0.71 to 1.84) |

| Residence (vs urban) | 0.59* | (0.38 to 0.91) | 0.55** | (0.35 to 0.85) | 0.59* | (0.38 to 0.92) |

| Living arrangement (vs not alone) | 0.73 | (0.40 to 1.34) | 0.69 | (0.38 to 1.27) | 0.73 | (0.40 to 1.35) |

| Education (vs illiteracy) | 1.36 | (0.99 to 1.84) | 1.49* | (1.09 to 2.03) | 1.43* | (1.05 to 1.95) |

| Occupation (vs farmer) | 1.90** | (1.22 to 2.96) | 2.05** | (1.32 to 3.20) | 1.87** | (1.17 to 2.90) |

| Lifestyle factors | ||||||

| Current smoker (vs no) | 0.83 | (0.46 to 1.49) | 0.87 | (0.48 to 1.55) | ||

| Current drinker (vs no) | 1.29 | (0.80 to 2.10) | 1.37 | (0.84 to 2.23) | ||

| Social activity (vs no) | 0.43 | (0.15 to 1.20) | 0.44 | (0.16 to 1.24) | ||

| Gardening (vs no) | 0.80 | (0.44 to 1.45) | 0.85 | (0.47 to 1.54) | ||

| Playing card/mah-jong (vs no) | 0.62 | (0.34 to 1.15) | 0.64 | (0.34 to 1.17) | ||

| Listening to radio/watching TV (vs no) | 0.65* | (0.42 to 0.99) | 0.65 | (0.42 to 1.00) | ||

| Health status | ||||||

| Hypertension (vs no) | 1.21 | (0.72 to 2.04) | ||||

| Diabetes (vs no) | 2.92* | (1.19 to 7.11) | ||||

| Stroke or cerebrovascular disease (vs no) | 1.80 | (0.89 to 3.67) | ||||

| ADL disability (vs no) | 1.56* | (1.01 to 2.40) | ||||

*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

ADL, activities of daily life; TV, television.

Discussion

In this population-based longitudinal study, we examined the causal association between exercise and the risk of dementia among older Chinese adults (aged 65 years or older). We found that 336 out of 7501 participants developed dementia during the 9-year follow-up period. Moreover, exercise was associated with reduced odds of dementia (OR=0.53, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.85), even after controlling for demographic characteristics, lifestyle factors and health status variables.

Our findings were consistent with those of most previous studies. A 6-year cohort study including 1740 people older than 65 years of age in the USA revealed that regular exercise was associated with delayed dementia development.10 Some studies have also suggested that regular exercise may serve as an effective intervention for dementia. For example, a randomised control trial including sedentary older adults without dementia found that a 12-month regular exercise (walking) programme significantly increased the hippocampal volume, which corresponded to 1–2 years delay in the onset of dementia.18 However, one study19 also using the CLHLS dataset showed that physical activity, but not exercise, was associated with cognitive impairment. These findings were based on a 2-year (1998–2000) cohort, and only baseline variables were controlled for in the models. In contrast, the data included in the present study were drawn from a 9-year prospective cohort with a relatively large sample size occurring from 2002 to 2011–2012. Furthermore, time-lagged GEE models were applied to make full use of the time-varying variables measured at each wave. This approach enabled us to obtain more reasonable and accurate results over the course of 9 years, instead of only using baseline variables, which was common in previous studies and may lead to residual confounding.

Our data underscore the importance of promoting exercise among older adults. As China progresses into an ageing society, the mounting challenges associated with caring for a population that is growing older require more effective public health programmes. Promoting exercises in the general population, especially among older adults, as suggested by the current study, can be an effective intervention for dementia prevention. China’s rapid urbanisation has been accompanied by more high-rise buildings and shrinking recreational public spaces, which have been linked to accelerating rates of obesity, cardiovascular diseases and dementia.19 Joint multisectorial efforts will be required to create social and physical environments that are conducive to engagement in regular exercise among the general public.

Potential mechanisms

There are three possible explanations for our results. First, exercise may have protective effects against dementia via neurotropic mechanisms7 and regulate gene expression, thereby affecting neuronal plasticity.20 Second, the relationship observed between exercise and dementia might be weakened by different types of cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors, which have been found to be the contributing factors for dementia.21 However, in the current study, after we controlled for risk factors, including hypertension and diabetes, exercise was still significantly associated with dementia, suggesting that exercise may have an independent protective effect. The third explanation is that regular exercise might be an indicator of having a healthy lifestyle, such as being more socially active, gardened, played cards/mah-jong or listened to radio/watched television, which may keep the brain active and stimulated, thus reduce the risk of dementia, according to ‘use it or lose it’ hypothesis.22 The associations between exercise and lifestyle factors were statistically significant in univariate analysis but ORs for lifestyle factors were non-significant in GEE models, which may be due to the insufficient sample size or potential multicollinearity.

Limitations

Our study had the following limitations. First, we were unable to further classify dementia into Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia, which may have resulted in a potential confounding bias; for example, stroke or cerebrovascular disease is strongly associated with vascular dementia. Second, the measurement of regular exercise was based on self-report data and was not comprehensive. The relationships between the type, frequency, duration and intensity of exercise, and dementia development were not examined because this information was not available in the CLHLS database. Third, dementia is a chronic disease without effective early diagnostic tools; thus, some patients with dementia might have been classified as dementia-free in our analysis. In addition, dementia was defined as a self-reported or proxy-reported physician’s diagnosis of the disease, as indicated in the CLHLS database. The prevalence of self-reported dementia in this study is parallel to that in China3 and countries in East Asia.23

Conclusion

Despite the aforementioned limitations, this study is one of the first to examine the relationship between regular physical exercise and dementia development in China using data from a national longitudinal dataset. Therefore, the findings from our analysis might be generalisable to the population of Chinese adults aged 65 years or older. The results of our study suggested that exercise was associated with significantly reduced risk of dementia. As no effective treatment for dementia is currently available, it is crucial to promote regular physical exercise to prevent dementia. Healthcare providers should advise patients and the general public to adopt healthy lifestyles, including regular exercise. Policy-makers should develop effective public health programmes and build exercise-friendly environments for the general public. Future studies are needed to confirm whether the specific type (such as walking, running, playing ball games, among others), intensity or frequency of exercise may associate with the risk of dementia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The data used in this research were provided by the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS) study, which was managed by the Center for Healthy Ageing and Development Studies, Peking University. The CLHLS was supported by funds from the US National Institute on Ageing (NIA), China Natural Science Foundation, China Social Science Foundation and United Nations Fund for Population Activities (UNFPA). We thank American Journal Experts (AJE) for English language editing.

Footnotes

Contributors: YF conceived and designed the study, and supervised the data analysis. ZZ and JF analysed the data and wrote the paper together. YAH helped with revising the manuscript. PW gave advice on statistical analysis. All authors have given final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 81602941, 81573257) and the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province of China (grant number: 2016J0101).

Disclaimer: The funding agencies are not responsible for the opinions presented in the manuscript. The funding bodies had no influence on the conduct of the study or the interpretation of the results.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The use of CLHLS data was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Peking University (IRB00001052-13074).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is conditionally available. For details of access permitting, please check the website at http://web5.pku.edu.cn/ageing/html/datadownload.html.

References

- 1. Morse RJ, DuBeau CE. Update in geriatric medicine: evidence published in 2014. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:W102–5. 10.7326/M15-0298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO. 10 Facts on dementia. Secondary 10 Facts on dementia, 2015. http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/dementia/en/ (20 Sept 2017).

- 3. Wu YT, Lee HY, Norton S, et al. . Prevalence studies of dementia in mainland china, Hong Kong and taiwan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2013;8:e66252 10.1371/journal.pone.0066252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wimo A, Winblad B, Jönsson L. An estimate of the total worldwide societal costs of dementia in 2005. Alzheimers Dement 2007;3:81–91. 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tanigawa T, Takechi H, Arai H, et al. . Effect of physical activity on memory function in older adults with mild Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2014;14:758–62. 10.1111/ggi.12159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Larson EB, Wang L, Bowen JD, et al. . Exercise is associated with reduced risk for incident dementia among persons 65 years of age and older. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:73–81. 10.7326/0003-4819-144-2-200601170-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Laver K, Dyer S, Whitehead C, et al. . Interventions to delay functional decline in people with dementia: a systematic review of systematic reviews. BMJ Open 2016;6:13:e010767 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Bienias JL, et al. . Cognitive activity and incident AD in a population-based sample of older persons. Neurology 2002;59:1910–4. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000036905.59156.A1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Morgan GS, Gallacher J, Bayer A, et al. . Physical activity in middle-age and dementia in later life: findings from a prospective cohort of men in Caerphilly, South Wales and a meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis 2012;31:569–80. 10.3233/JAD-2012-112171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chan KY, Wang W, Wu JJ, et al. . Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia in China, 1990-2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet 2013;381:2016–23. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60221-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zeng Y, Cheng L, Zhao L, et al. . Interactions between social/ behavioral factors and ADRB2 genotypes may be associated with health at advanced ages in China. BMC Geriatr 2013;13:91 10.1186/1471-2318-13-91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Han WJ, Shibusawa T. Trajectory of physical health, cognitive status, and psychological well-being among Chinese elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2015;60:168–77. 10.1016/j.archger.2014.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gu D. General data assessment for the 2005 waves of the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey. The technical report No. Durham, NC USA: 1Duke University, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yi Z, et al. . Introduction to the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS) : Yi Z, Poston D J, Vlosky D, Springer Netherlands: Healthy Longevity in China, 2008:23–38. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Glymour MM, Avendano M. Can self-reported strokes be used to study stroke incidence and risk factors?: evidence from the health and retirement study. Stroke 2009;40:873–9. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.529479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Andel R, Crowe M, Pedersen NL, et al. . Physical exercise at midlife and risk of dementia three decades later: a population-based study of Swedish twins. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2008;63:62–6. 10.1093/gerona/63.1.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schafer JL, Olsen MK. Multiple Imputation for Multivariate Missing-Data Problems: a data analyst’s perspective. Multivariate Behav Res 1998;33:545–71. 10.1207/s15327906mbr3304_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Erickson KI, Voss MW, Prakash RS, et al. . Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011;108:3017–22. 10.1073/pnas.1015950108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee L. The current state of public health in China. Annu Rev Public Health 2004;25:327–39. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hillman CH, Erickson KI, Kramer AF. Be smart, exercise your heart: exercise effects on brain and cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci 2008;9:58–65. 10.1038/nrn2298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kivipelto M, Helkala EL, Laakso MP, et al. . Midlife vascular risk factors and Alzheimer’s disease in later life: longitudinal, population based study. BMJ 2001;322:1447–51. 10.1136/bmj.322.7300.1447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Swaab DF. Brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease, "wear and tear" versus "use it or lose it". Neurobiol Aging 1991;12:317–24. 10.1016/0197-4580(91)90008-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Prince M, Wimo A, Guerchet M, et al. . World Alzheimer Report 2015: The Global Impact of Dementia: an Analysis of Prevalence, Incidence, Cost and Trends. London, England: Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.