Abstract

Introduction

Despite advances in infection prevention and control, catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs) are common and remain problematic. A number of measures can be taken to reduce the risk of CAUTI in hospitals. Appropriate urinary catheter insertion procedures are one such method. Reducing bacterial colonisation around the meatal or urethral area has the potential to reduce CAUTI risk. However, evidence about the best antiseptic solutions for meatal cleaning is mixed, resulting in conflicting recommendations in guidelines internationally. This paper presents the protocol for a study to evaluate the effectiveness (objective 1) and cost-effectiveness (objective 2) of using chlorhexidine in meatal cleaning prior to catheter insertion, in reducing catheter-associated asymptomatic bacteriuria and CAUTI.

Methods and analysis

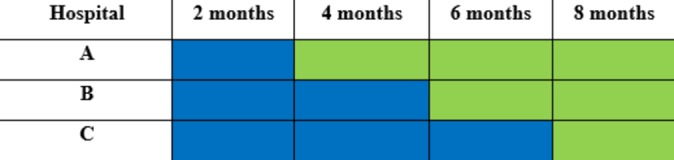

A stepped wedge randomised controlled trial will be undertaken in three large Australian hospitals over a 32-week period. The intervention in this study is the use of chlorhexidine (0.1%) solution for meatal cleaning prior to catheter insertion. During the first 8 weeks of the study, no hospital will receive the intervention. After 8 weeks, one hospital will cross over to the intervention with the other two participating hospitals crossing over to the intervention at 8-week intervals respectively based on randomisation. All sites complete the trial at the same time in 2018. The primary outcomes for objective 1 (effectiveness) are the number of cases of CAUTI and catheter-associated asymptomatic bacteriuria per 100 catheter days will be analysed separately using Poisson regression. The primary outcome for objective 2 (cost-effectiveness) is the changes in costs relative to health benefits (incremental cost-effectiveness ratio) from adoption of the intervention.

Dissemination

Results will be disseminated via peer-reviewed journals and presentations at relevant conferences. A dissemination plan it being developed. Results will be published in the peer review literature, presented at relevant conferences and communicated via professional networks.

Ethics

Ethics approval has been obtained.

Trial registration number

12617000373370, approved 13/03/2017. Protocol version 1.1.

Keywords: urinary tract infections, health economics, infection control

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Randomised control design

Evaluation of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness

Limited to hospitals in high-income country

Introduction

Indwelling urinary catheters are commonly used in healthcare facilities, with foundation work indicating that 26% of patients admitted to an Australian hospital receive an indwelling urinary catheter and 1% of these patients develop catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs).1CAUTIs have been associated with increased morbidity, mortality, increased length of stay in hospital and higher hospital costs for patients and health systems.2 Data from the International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) surveillance study, conducted in 703 intensive care units in low and middle-income countries, suggest the incidence of CAUTI to be 4.8 per 1000 device days (years 2010–2015).3 In Australia, an estimated 380 000 bed days are lost each year due to healthcare-associated urinary tract infections (UTIs), a large proportion of which are CAUTIs. CAUTIs are also associated with higher risk of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), making the treatment of patients difficult.4 5AMR in UTIs has also been shown to be increasing globally, further emphasising the need to develop interventions to reduce the incidence of CAUTIs.6

Studies have shown that the incidence of CAUTI can be reduced.7 8 Nonetheless, despite some advances in infection prevention and control, CAUTIs remain problematic.9 Evidence shows that reducing bacterial colonisation around the meatal or urethral area has the potential to reduce CAUTI risk.10 However, evidence about the best antiseptic solutions for meatal cleaning is mixed. Previous research also identified a lack of documentation and knowledge in relation to the meatal cleaning solution used prior to catheter insertion.1 Unsurprisingly, there is variation in practice within Australian hospitals with respect to catheter insertion, and specifically the agent used to clean the meatal area prior to insertion. These issues provided a strong rationale for the study investigators to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of published literature, investigating the effectiveness of antiseptic cleaning during urinary catheter insertion for the prevention of CAUTI.11 This review of current research knowledge identified the need for a well-designed intervention study as well as a limited number of studies evaluating the cost-effectiveness of using an antiseptic during catheter insertion. As health budgets are finite, clinical practice needs to use cost-effective strategies. The cost of chlorhexidine 0.1% solution is considerably higher than 0.9% normal saline.

Given the importance of meatal colonisation in the pathogenesis of CAUTIs, emerging AMR, the frequency with which catheters are used and the burden of CAUTIs in Australia and in hospital settings worldwide, the generation of evidence using a high-quality randomised trial is needed to determine the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of meatal cleaning. This will inform infection prevention and control practice and policy in Australia and internationally.

Trial objectives

The trial objectives listed below pertain to both the cluster and individual level. The trial is registered with the Australia New Zealand Clinical Trial Registry (No 12617000373370).

Objective 1

The first objective is to evaluate the effectiveness of using chlorhexidine in meatal cleaning prior to catheter insertion, in reducing catheter-associated asymptomatic bacteriuria (CA-ASB) and CAUTI.

Objective 2

The second objective is to estimate the cost-effectiveness of the decision to adopt chlorhexidine in meatal cleaning prior to catheter insertion.

Methods

Study design

A stepped wedge randomised controlled trial will be undertaken in three large hospitals over a 32-week period (example trial timing are in figure 1). The stepped wedge design includes an initial period where no hospitals are exposed to the intervention.12 Afterwards, at 8-week intervals (the ‘steps’) each hospital sequentially crosses over from the control to the intervention until all hospitals are exposed to the intervention for the final 8 weeks until conclusion in week 32. The study design enables each hospital to act as its own control, which removes the potential for some confounders such as variations in hospital size and case mix and differences between public and private hospitals. Staggered commencement and duration of the intervention supports feasibility while maintaining the rigour of the study.13 This design will also allow research staff to work with individual hospitals as they change over, maximising consistency of intervention and aiding implementation.13 In addition, data collection continues throughout the study, so that each cluster contributes observations under both control and intervention observation periods.

Figure 1.

Study design overview. Blue, control; green, intervention.

Study population

Three Australian hospitals that fulfil the eligibility criteria will be enrolled in the study. These criteria are as follows:

Has an intensive care unit

Be classified by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare as a principal referral hospital OR a public acute group A hospital (with more than 400 beds), OR in the case of a private hospital has 400 inpatient beds OR has more than 30 000 patient admissions per year.

Other considerations

Hospitals could be excluded from the study if within the study time frame they are

undertaking a project that may influence the outcomes measured in this study

opening, closing or relocating.

Areas of hospital and patient-level inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study will be a hospital wide study, but will exclude patients with indwelling urinary catheters within a hospital that are not considered appropriate for the intervention, for example neonatal intensive care. Patients <2 years old, with an allergy, contraindication or other medical reason preventing the use of the intervention for cleaning the urethral meatal area will be excluded. Patients who require in-and-out or suprapubic catheterisation will also be excluded as well as those with symptoms and signs suggestive of UTI and patients already undergoing treatment for UTI. All data from any patient lost to follow-up (postcatheter insertion) will be excluded.

Recruitment

The study team will list all eligible sites then order the list to ensure (1) a representation of both private and public hospitals and (2) representation from at least two Australian states and territories. The recruitment process will purposively select and approach eligible hospitals to optimise the feasibility and practicality of completing the trial.

Intervention

The intervention in this study is the use of chlorhexidine (0.1%) solution for meatal cleaning prior to catheter insertion. The control is the use of normal saline (0.9%) for meatal cleaning. During the first 8 weeks of the study, no hospital will receive the intervention. After 8 weeks, one hospital will cross over to the intervention with the other two participating hospitals crossing over to the intervention at 8-week intervals respectively based on randomisation.

Implementing the intervention

In the week prior to the intervention commencing, information sessions about the study will be provided to participating hospitals and staff. A variety of methods will be used to further alert staff and raise awareness about the intervention prior to it being rolled out. These methods include placing wall posters in wards and key hospital locations, handing out hospital newsletters and information leaflets as well as branded promotional material, such as pens. To avoid potential confounding, information and awareness sessions are limited to just the change of product, not education around catheter insertion or management practices.

Chlorhexidine 0.1% solution will be used by clinical staff at participating hospitals for cleaning the meatal area of patients prior to urinary catheter insertion. To aid implementation of the intervention, investigators will work with participating hospitals and use hospital data collection and reporting systems currently in place. This will involve incorporation of the 0.1% chlorhexidine solution into existing catheter procedure packs at the hospitals where possible, visual reminders where urinary catheters are stored and temporary amendment to hospital procedural documentation.

As per hospital’s usual practice, details of the catheter insertion will be documented by clinical staff. To achieve optimal documentation of the procedure, catheter insertion stickers may be made available to hospitals for use in patients’ medical notes.

Potential confounders

Lubricants are used during the catheter insertion process and may contain an antiseptic. The lubricant used during the entire study (control and intervention periods) will remain constant in each hospital.

Randomisation and blinding

Hospitals will be randomly assigned to one of three dates to cross over to the intervention which will occur once every 8 weeks over the trial duration of 32 weeks. All included hospitals will be provided with sufficient notice of the dates to cross over to the intervention. Computer-generated randomisation of the cross over dates for the hospitals will be performed independently by an investigator not involved in assessment or delivery of the intervention. Hospitals will not be blinded because it is not feasible to blind staff administering the intervention. The outcome of the randomisation process will be revealed by the project manager to the participating hospitals prior to the commencement of the study.

Outcomes and definitions

The outcomes for each objective are outlined in table 1. For objective 1, the primary outcomes are the cases of CA-ASB and CAUTI. For objective 2, the primary outcome is the cost-effectiveness of the intervention.

Table 1.

Key outcome measures

|

Objective 1

Effectiveness of using chlorhexidine in meatal cleaning prior to catheter insertion |

Primary outcome | The number of cases of CA-ASB per 100 catheter days The number of cases of CAUTI per 100 catheter days |

| Secondary outcome | The number of BSIs associated with a UTI | |

|

Objective 2

Cost-effectiveness of the intervention |

Primary outcome | Changes in costs relative to health benefits (incremental cost-effectiveness ratio) from adoption of the intervention Changes in costs associated with implementing the intervention relative to the change in QALYs |

BSI, blood stream infection; CA-ASB, catheter-associated asymptomatic bacteriuria; CAUTI, catheter-associated urinary tract infection; QALY, quality-adjusted life years; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Catheter-associated asymptomatic bacteriuria is defined as the presence of ≥105 colony-forming unit (cfu)/ml of ≥1 bacterial species in a single catheter urine specimen in a patient without symptoms compatible with UTI.14

Catheter-associated urinary tract infection is defined according to the National Healthcare Safety Network criteria.15 16 A patient must meet all three criteria below:

Patient had an indwelling urinary catheter that had been in place for >2 days on the date of event (day of device placement=day 1) AND was either present for any portion of the calendar day on the date of event or removed the day before the date of event.

Patient has at least one of the following signs or symptoms: fever (>38.0°C); suprapubic tenderness; costovertebral angle pain or tenderness; urinary urgency; urinary frequency; dysuria.

Patient has a urine culture with no more than two species of organisms identified, at least one of which is a bacterium of ≥105 cfu/mL.

Blood stream infection (BSI) associated with a UTI is defined according to National Healthcare Safety Network criteria.15 A patient must meet the definition for CAUTI and has at least one organism from the blood specimen that matches an organism identified in the urine specimen that is used as an element to meet the CAUTI criterion. The blood specimen must be collected during the secondary BSI attribution period when the urinary catheter is in place.

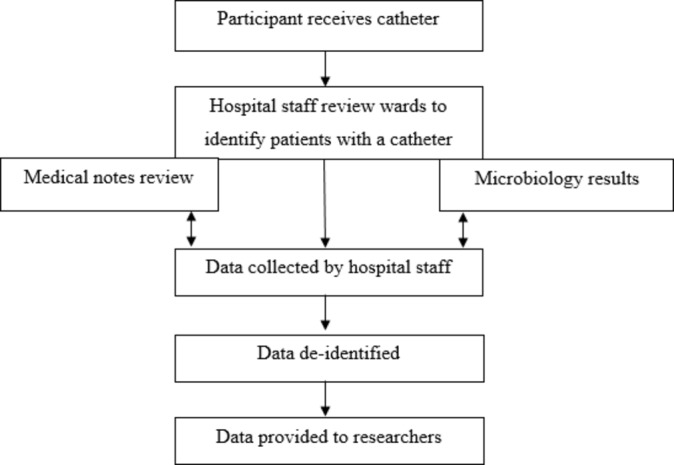

Data collection

Data will be collected by a specific staff member or members at the hospital, with the support of the research team. The research team will provide the hospital staff member(s) with training about the project, data collection and submission process and data collection tools. For the purpose this paper, the dedicated hospital staff member(s) will be referred to as hospital personnel. Figure 2 summarises the data collection process.

Figure 2.

Overview of data collection process.

Hospital personnel will prospectively collect data 3 days a week at each hospital during both control and intervention periods. Patients who receive an indwelling urinary catheter will be identified and followed-up during the trial period (for a period of 7 days postcatheter insertion, discharge or 48 hours postcatheter removal—whichever occurs first). Medical notes of patients will be reviewed to obtain demographic and clinical data such as hospital number, age, sex, date of admission, signs or symptoms of UTI. Co-morbidity data will be collected where possible.

Details of catheter insertion specifically date and time of insertion, designation of person inserting catheter, catheter type and catheter size will also be obtained from the patients’ medical notes (where documented). If the insertion date is not documented, the patient will be excluded from the study. Denominator data on the number of catheter days over the trial period will be collected at each hospital during both control and intervention periods. The number of catheter days for each patient included in the study will be estimated from the date of catheter insertion and date of removal. Hospital personnel will record all captured data in a spreadsheet designed specifically for the purpose of the trial.

Information for the primary (CA-ASB and CAUTI) and secondary (BSI) outcome measures will be collected from the microbiology laboratory database of participating hospitals. Results of all positive urine cultures either attributable to bacteriuria or true UTI as well as positive blood cultures are registered in hospital microbiology laboratory databases. Hospital personnel will obtain weekly reports from the microbiology laboratory of participating hospitals to identify the outcomes. The patient record number will be used to link demographic and clinical data of patients with a urinary catheter to microbiology laboratory data. To differentiate between CA-ASB and CAUTI, additional data on symptoms and signs of UTI will be collected from patients’ medical notes by research assistants.

Information to inform changes to total costs and health benefits from a decision to adopt the intervention will be obtained. Changes to costs will include the resources required to implement the intervention and the changes to use of health services. Changes to health benefits will be captured by estimating quality-adjusted life years (QALY) outcomes. Hospital personnel will prospectively obtain monthly data from each participating hospital on the cost of purchasing resources, such as catheter procedure packs, used for implementing the intervention. Hospital personnel will also obtain data on antimicrobial use for patients, specifically the name, dose and duration of antimicrobial, which will be used for estimating antimicrobial therapy costs in control and intervention periods. Hospital staff involved in the trial will be surveyed immediately following completion of the intervention to evaluate extra staff time spent in activities related to planning and implementing the intervention. To calculate QALYs, primary data on age obtained from medical notes of patients will be used along with estimates from the published literature.17

Power calculation

Sample size and power were calculated on the basis of CAUTI, as it is assumed that the power to detect an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was greater than that for relevant clinical endpoints. The at-risk population are those that receive a catheter while in hospital. Based on pilot work, the estimated proportion of patients developing a CAUTI for this study is 3.4%.1 We estimate a 20% reduction using a Cohen’s d size effect measure at 0.2 (small effect). Based on individual randomisation of two groups (control and intervention), power of 80%, alpha of 0.05%, effect size of 0.2 and two-sided test for comparison of two means were estimated. As this is a stepped wedge design, we have used a sample size formula from Hussey and Hughes and operationalised the design effect from Hemming.12 18 For the design effect, we have assumed three hospitals, three time periods, with N1 being the sample size of 784. Three different scenarios were modelled, each with different intracluster correlation coefficients—0.1, 0.05, 0.01. An intracluster correlation coefficient of 0.05 was subsequently determined and the sample size (m=220, M=880) for each cluster.

Pilot work identified that 26% of patients admitted to hospital in Australia receive a urinary catheter.1 19 As we are excluding patients who had a catheter inserted in theatre, we estimated that 5% of admitted patients receive a catheter not inserted in theatre. To obtain the required sample size in each hospital, a hospital is to have at least 30 000 patient admissions per year.

Analysis

Objective 1: effectiveness of using chlorhexidine in meatal cleaning prior to catheter insertion

The number of CA-ASB, CAUTI and BSI will be analysed separately using Poisson regression, with the number of cases as the dependent variable and number of patient catheter days as the denominator. This denominator will help control for changes in catheter use during the study period. The key independent variable will be the intervention. The key outcomes will be estimated reduction in cases of CA-ASB, CAUTI and BSI due to the intervention. The characteristics of the hospital (eg, size) will not be independent variables as these should remain roughly constant throughout the study observations. There is no expected delay in the effect of intervention on the outcome.

Objective 2: cost-effectiveness of the intervention

The effectiveness data from objective 1 will be a key parameter in the cost-effectiveness model. Final outcomes for the cost-effectiveness evaluation are the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio estimated as the cost per QALY gained, and the changes to costs in QALYs. Published guidelines for costing an intervention will be followed.20 The changes to costs from adopting the intervention will be estimated by the extra staff time spent both planning and implementing the intervention, converted to a dollar figure using full employment costs. Other costs are product costs. These cost data will be collected prospectively on a monthly basis for product costs and a survey immediately after the intervention is implemented (staff costs). Quantities of resources will be standardised to all hospitals to ensure valid comparison of costs across all sites. This will reduce uncertainty in estimates which often results from using retrospective administrative data.

The major cost savings from reducing infections are characterised by the bed days saved from keeping patients infection free and hence discharging them earlier. The reasoning is that 90% of the costs of hospital services are fixed so bed days saved are an appropriate currency. Data from a previous study using multistate modelling to estimate the extra length of stay per case of urinary bacteriuria will be used in the model.21 Other cost savings are averted laboratory diagnosis costs and antimicrobial therapy costs, estimated by counting the frequency of laboratory tests and antimicrobial therapy costs in the control and intervention periods. These will be collected prospectively as part of the data collection process. Laboratory costs using the relevant medical benefit scheme item costs will be used. For antimicrobial therapy costs, pharmaceutical benefits scheme costs will be used.

Changes to health benefits will be informed by the extra death risk due to infection. This parameter will come from a previously described analysis of mortality associated with urinary bacteriuria. These estimates used multistate models that avoid time and length biases to estimate increases in mortality attributable to infection. The results are HRs that can be used to predict reduction in deaths from avoided infections. The mean age of hospital patients will be used to predict years of life gained and preference-based utility scores will be used to weight life expectancy, allowing us to calculate QALYs. We will not collect primary data on preference-based utility scores. Instead, these estimates will be taken from the published literature.22

The change to total costs at the hospital level will be estimated by summing intervention costs and deducting cost savings from reduced lengths of stay and use of healthcare resources that arise from reduced incidences of infection. The changes to health benefits will be estimated in QALYs using the number of life years saved from reduced infection outcomes; the expected duration of life (had infection not occurred) based on age and data from the published literature.17 All costs and health benefits arising in future periods will be appropriately discounted. Uncertainties in parameter estimates will be captured using appropriate statistical distributions to describe the variability. For example, the beta distribution would be a good choice for infection risk as this distribution is restricted to interval 0–1. The parameters of the beta distribution will be chosen to reflect what we know about the mean and range in infection risk (eg, a beta distribution with a mean rate of infection of 0.003% and 95% CI of 0.001 to 0.005). The fitted distributions will be subject to random re-samples simulated 10 000 times. The distributions of all prior parameters are used to estimate the posterior distributions of ‘change to costs’ and ‘change to QALY’ outcomes.

The decision will be informed by plotting cost-effectiveness acceptability curves with threshold value between zero and 100 000 per QALY gained, and using the net monetary benefits framework.

These approaches are semi-Bayesian and appropriately account for all parameter uncertainty for the adoption decisions.

Discussion

This study addresses an identified gap in infection control research and practice. Despite the frequency of UTIs associated with indwelling urinary catheter use, there are few studies focusing on their surveillance and prevention. Aligning with the emphasis on quality and safety, this multicentre randomised controlled trial will evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an antiseptic versus non-antiseptic meatal cleaning agent to prevent CAUTIs, a world first. The ultimate objective is the prevention of healthcare-related CAUTIs, leading to benefits for patient safety.

Strengths

Few randomised controlled trials have investigated the effectiveness of antiseptics on CAUTI incidence during urinary catheter insertion, and previous research has been limited mainly due to the lack of an appropriate sample size to demonstrate any possible beneficial effect from the use of antiseptics.11 Our study uses a rigorous approach and is sufficiently powered to detect the effect of antiseptics in reducing CAUTI. The inclusion of the cost-effectiveness analysis is an additional strength of this trial as to our knowledge previous trials have not evaluated the cost-effectiveness of an antiseptic meatal cleaning agent in reducing CAUTI. Over the past decade, cost-effectiveness analysis has evolved further emphasising the need to address this evidence gap.

This randomised controlled trial is also strengthened by the use of a stepped wedged design which has been found to be particularly useful in studies evaluating intervention effectiveness during routine implementation such as in the case of this study where the insertion of a urinary catheter is considered to be part of the care of the patient.23 The study design also enables each hospital to act as its own control, which removes the potential for some confounders such as variations in hospital size and case mix and differences between public and private hospitals. Furthermore, this study identifies best practice among current practice.

Limitations

Exclusion of patients who have indwelling urinary catheters inserted in surgical theatre has the potential to prolong recruitment of participants given that surgical procedures are a common indication for urinary catheter insertion.24 25 However, recruitment of these patients was not deemed feasible as it would require involvement of all surgeons including theatre staff in the study. Unless the participating hospital can achieve implementation in theatre, patients who have catheters inserted in theatres will be excluded. The initiatives taken to introduce the intervention may inadvertently improve catheter management. To reduce this effect, no education on other aspects of catheter management (other than the product change) will be provided to staff.

Significance

It is important that urinary catheter insertion strategies for CAUTI prevention are supported by evidence obtained from rigorously conducted research. This study’s significance therefore lies in its ability to inform recommendations within national infection control guidelines globally. This study will also contribute to the development of strategies to reduce the incidence of CAUTI using cost-effective approaches. This is even more important in the context of finite health budgets.

Trial status

The study team is completing the recruitment of participating hospitals. The trial is due to commence in late 2017.

Data quality

Data will be stored in electronically in a secure (password protected) location, by chief investigator BM at Avondale College of Higher Education. Data quality will be enhanced by the provision of adata collection form, quality checks by the project manager. A data collection guide has been developed to aide and document this process. Data monitoring will be overseen by chief investigator BM and the data monitoring committee consists of all chief investigators on the study. Any approved changes to the study protocol will be updated in Australia New Zealand Clinical Trial Registry

Access to data

Chief investigator BM will hold data during and after study completion

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors made contributions to the development of the trial protocol and have been involved in drafting this manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content. BM is the overall chief investigator. BM and AC lead on epidemiology and infection control. PC leads on infectious diseases. AC and PM lead on statistics. NG leads on health economics. AG and JK lead on health policy and decision making. OF leads on urinary tract infection. VG is the project manager. BM and OF led the initial protocol development. All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the HCF Foundation and cash support from Avondale College of Higher Education. The contents of the published material are solely the responsibility of the administering institution.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This project has received ethics approval from Avondale College of Higher Education Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) (approval number 2017:03), the Australian Capital Territory HREC (approval number ETH.4.17.083) and the Adventist HealthCare Limited Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number 2017-018). A waiver of individual patient consent was granted for this study. Any risks or harms associated with the study will be reported to the relevant HREC. Reporting of the trial and progress, including any audits, will be conducted consistent with the requests of the HRECs who approved the study. Any modification to the study that has ethical implications will be forwarded to the HRECs for approval. No identifiable or re-identifiable patient data will be collected by the researchers, thus protecting anonymity and confidentiality of participants.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Gardner A, Mitchell B, Beckingham W, et al. . A point prevalence cross-sectional study of healthcare-associated urinary tract infections in six Australian hospitals. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005099 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Saint S. Clinical and economic consequences of nosocomial catheter-related bacteriuria. Am J Infect Control 2000;28:68–75. 10.1016/S0196-6553(00)90015-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rosenthal VD, Al-Abdely HM, El-Kholy AA, et al. . International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium report, data summary of 50 countries for 2010-2015: Device-associated module. Am J Infect Control 2016;44:1495–504. 10.1016/j.ajic.2016.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nicolle LE. Catheter associated urinary tract infections. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2014;3:23 10.1186/2047-2994-3-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organisation. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance: Geneva World Health Organisation, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fasugba O, Mitchell BG, Mnatzaganian G, et al. . Five-year antimicrobial resistance patterns of urinary escherichia coli at an Australian tertiary hospital: time series analyses of prevalence data. PLoS One 2016;11:e0164306 10.1371/journal.pone.0164306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rosenthal VD, Ramachandran B, Dueñas L, et al. . Findings of the International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC), Part I: Effectiveness of a multidimensional infection control approach on catheter-associated urinary tract infection rates in pediatric intensive care units of 6 developing countries. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2012;33:696–703. 10.1086/666341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rosenthal VD, Todi SK, Álvarez-Moreno C, et al. . Impact of a multidimensional infection control strategy on catheter-associated urinary tract infection rates in the adult intensive care units of 15 developing countries: findings of the International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC). Infection 2012;40:517–26. 10.1007/s15010-012-0278-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Saint S, Greene MT, Krein SL, et al. . A program to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infection in acute care. N Engl J Med 2016;374:2111–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa1504906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Warren JW. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2001;17:299–303. 10.1016/S0924-8579(00)00359-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fasugba O, Koerner J, Mitchell BG, et al. . Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of antiseptic agents for meatal cleaning in the prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. J Hosp Infect 2017;95:233–42. 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hemming K, Haines TP, Chilton PJ, et al. . The stepped wedge cluster randomised trial: rationale, design, analysis, and reporting. BMJ 2015;350:h391 10.1136/bmj.h391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hall L, Farrington A, Mitchell BG, et al. . Researching effective approaches to cleaning in hospitals: protocol of the REACH study, a multi-site stepped-wedge randomised trial. Implement Sci 2016;11:44 10.1186/s13012-016-0406-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hooton TM, Bradley SF, Cardenas DD, et al. . Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 International Clinical Practice Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50:625–63. 10.1086/650482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC/NHSN surveillance definitions for specific types of infections, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Urinary tract infection (Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection [CAUTI] and Non-Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection [UTI]) and Other Urinary System Infection [USI]) Events Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bermingham SL, Ashe JF. Systematic review of the impact of urinary tract infections on health-related quality of life. BJU Int 2012;110:E830–836. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11337.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hussey MA, Hughes JP. Design and analysis of stepped wedge cluster randomized trials. Contemp Clin Trials 2007;28:182–91. 10.1016/j.cct.2006.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mitchell BG, Fasugba O, Beckingham W, et al. . A point prevalence study of healthcare associated urinary tract infections in Australian acute and aged care facilities. Infection, Disease & Health 2016;21:26–31. 10.1016/j.idh.2016.03.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Page K, Graves N, Halton K, et al. . Humans,‘things’ and space: costing hospital infection control interventions. J Hosp Infect 2013;84:200–5. 10.1016/j.jhin.2013.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mitchell BG, Ferguson JK, Anderson M, et al. . Length of stay and mortality associated with healthcare-associated urinary tract infections: a multi-state model. J Hosp Infect 2016;93:92–9. 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cuthbertson BH, Scott J, Strachan M, et al. . Quality of life before and after intensive care. Anaesthesia 2005;60:332–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.04109.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mdege ND, Man MS, Taylor Nee Brown CA, et al. . Systematic review of stepped wedge cluster randomized trials shows that design is particularly used to evaluate interventions during routine implementation. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:936–48. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tenke P, Kovacs B, Bjerklund Johansen TE, et al. . European and Asian guidelines on management and prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2008;31:68–78. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.07.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wald HL, Ma A, Bratzler DW, et al. . Indwelling urinary catheter use in the postoperative period: analysis of the national surgical infection prevention project data. Arch Surg 2008;143:551–7. 10.1001/archsurg.143.6.551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.