Abstract

Background

Studies have shown a mixed association between socioeconomic status (SES) and prevalent HIV infection across and within settings in sub-Saharan Africa. In general, the relationship between years of formal education and HIV infection changed from a positive to a negative association with maturity of the HIV epidemic. Our objective was to determine the association between SES and HIV in women of reproductive age in the Free State (FSP) and Western Cape Provinces (WCP) of South Africa (SA).

Study design

Cross-sectional.

Setting

SA.

Methods

We conducted secondary analysis on 1906 women of reproductive age from a 2007 to 2008 survey that evaluated effectiveness of Prevention of Mother-to-Child HIV Transmission Programmes. SES was measured by household wealth quintiles, years of formal education and employment status. Our analysis principally used logistic regression for survey data.

Results

There was a significant negative trend between prevalent HIV infection and wealth quintile in WCP (P<0.001) and FSP (P=0.025). In adjusted analysis, every additional year of formal education was associated with a 10% (adjusted OR (aOR) 0.90 (95% CI 0.85 to 0.96)) significant reduction in risk of prevalent HIV infection in WCP but no significant association was observed in FSP (aOR 0.99; 95% CI 0.89 to 1.11). There was no significant association between employment and prevalent HIV in each province: (aOR 1.54; 95% CI 0.84 to 2.84) in WCP and (aOR 0.96; 95% CI 0.71 to 1.30) in FSP.

Conclusion

The association between HIV infection and SES differed by province and by measure of SES and underscores the disproportionately higher burden of prevalent HIV infection among poorer and lowly educated women. Our findings suggest the need for re-evaluation of whether current HIV prevention efforts meet needs of the least educated (in WCP) and the poorest women (both WCP and FSP), and point to the need to investigate additional or tailored strategies for these women.

Keywords: hiv or aids, socioeconomic status, education

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our questionnaire and sampling methodology is similar to that widely used in Demographic and Health Surveys which enables easy comparison of our findings with those widely available in literature that use a similar methodology on a comparable population.

Our study uses three measures of socioeconomic status which is advantageous because different measures of socioeconomic status perform differently in relation to health outcomes in settings with widespread poverty and wide income inequality like South Africa.

Household wealth indices may not reflect women’s true financial status or access to funds in households in settings that have widespread gender inequality like South Africa.

Cross-sectional studies do not establish temporal or causal relationships but only depict associations.

Introduction

An estimated 36.7 million people were living with HIV globally in 2015, 7 million of whom were South Africans (SAs).1 Although health outcomes generally improve with increasing socioeconomic status (SES), this pattern has been mixed with regards to HIV in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) over the last three decades.2 3 SES is a complex composite measure that typically incorporates social, economic and employment status and is measured by education, income and occupation, respectively, which are interrelated but do not completely overlap.4

Globally, HIV burden is least in the richest countries, but in SSA countries HIV prevalence is highest in the wealthiest countries. In SSA countries, the positive correlation between national income and HIV prevalence at national level changes to a mixed correlation when household or individual income is correlated with HIV prevalence.5 Studies have shown a change of the association between HIV prevalence and years of formal education, from a positive to a negative association with maturity of the HIV epidemic,6–12 including a systematic review.13 The systematic review showed an overall increase in proportion of studies showing a negative association with maturity of HIV epidemics across SSA.6 The change from positive to negative association was hypothesised to be due, in part, to maturity of the HIV epidemic from early phases of the epidemic when infections are concentrated in high-risk core groups to advanced phases of the epidemic when HIV becomes a generalised epidemic.14 Early in the HIV epidemic, more educated individuals had more disposable income, were more mobile and were more likely to have broader sexual networks,13 15 including using services of commercial sex workers16 17 and being in concurrent sexual relationships.18 The change in association between years of formal education and HIV was attributed, in part, to faster increase in awareness, adoption of safer sexual practices and access to preventive and curative health services by the more educated individuals.19 However, SA study showed school dropouts have more intergenerational sex, higher lifetime number of sex partners, more frequent sex and higher incidence of unsafe sex as when compared with their peers who remain in school.20 Schooling affect sexual behaviour through various mechanisms including changes in sociocognitive determinants of behaviour such as knowledge and attitudes, influencing of social networks and by leading to improvement in SES.21

The correlation between wealth/poverty and HIV has been hypothesised to be bidirectional: an upstream effect of poverty on the likelihood of HIV infection and a downstream effect of HIV/AIDS illness on households’ poverty levels.22 The poor are likely to engage in transactional or age-disparate sexual relationships and have limited access to health infrastructure which increases their susceptibility to HIV infection. According to the downstream effect, HIV/AIDS can exacerbate household poverty via catastrophic household expenditure, for example, direct costs such as medical expenses, or loss of income.

In light of the demonstrated spatial and temporal variability of the outcome of the debate on whether relative wealth or relative poverty is a determinant of prevalent HIV infection in SA, it is imperative to further and continuously investigate and monitor this relationship to inform HIV prevention strategies. In this study, we investigate the association between SES, as measured by employment status, formal education and household wealth index, and prevalent HIV infection in women of reproductive age in the Free State Province (FSP) and Western Cape Province (WCP) of SA to better define this relationship in this context and thus clarify potential mixed findings. Crucially, our findings are context-specific to the FSP and the WCP of SA for women of reproductive age attending antenatal clinic which is the subpopulation that has the highest prevalence of HIV in SA.

Methods

This cross-sectional study is a secondary analysis of data from the Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission of HIV, Effectiveness in Africa and, Research and Linkages to HIV Care survey (PEARL study) conducted between June 2007 and October 2008 in WCP and FSP of SA, already reported elsewhere.23–28 HIV prevalence among women seeking antenatal clinic services in WCP was 16.1% whereas this was 32.9% for FSP at the time of the survey.29 Our study population includes participants from urban formal settlements, urban informal settlements and rural formal settlements. In SA, HIV prevalence is highest in urban informal settlements (19.9%) followed by rural informal settlements (13.4%), rural formal settlements (10.4%) then urban formal settlements (10.1%).30 Urban and rural informal settlements are generally under-resourced and lack some of the basic necessities such as formal housing, water, sanitation and access to preventive health services.30 Our primary study neither collected data on race nor conducted HIV testing on partners of study participants. However, the demographic profile at the time of conduct of the study showed that 99% and 80% of women in FSP and WCP, respectively, were black African with the rest being mostly of mixed race ancestry.

Our study population includes women of reproductive age with a HIV diagnosis and SES data. HIV testing was anonymously conducted by initial screening with Determine HIV-1 rapid antibody test (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, USA) at the University of Cape Town and the University of the Free State. Mothers were referred for HIV counselling and rapid antibody testing at nearest public clinics. SES was measured by three proxy variables, based on available data; the highest level of formal education attained, employment status and household wealth quintiles derived from household ownership of select durable assets and access to social amenities using the principal components analysis statistical methodology that is widely used in Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS). 31 32 DHS are an ongoing collaboration between the United States and 85 developing countries that conducts comparable nationally representative household surveys with a strong focus on indicators of fertility, reproductive health, maternal and child health, mortality, nutrition and health behaviours among adults. It is a key for monitoring vital statistics and population health indicators.33 We used province-specific relative household wealth scores to generate estimates for each province, that is, household wealth quintiles were generated separately for each province using data for the specified province only.

We used the two sample test of proportions, linear combination of variables (lincom) for survey data, χ2 test for trend, principal components analysis and logistic regression for survey data for our analysis which was conducted in STATA statistical software V.14.2 for Windows.34 Since our study population was obtained via two-stage sampling involving stratification and cluster sampling, our analysis, as required for survey data, took this into consideration. There were two strata, WCP and FSP, each with three separate communities (six in total) which were treated as six separate clusters in our design-adjusted analysis. There was significant intercluster heterogeneity in HIV prevalence for WCP (the three clusters in WCP had HIV prevalence of 7.6%, 2.3% and 25.9%) but not for FSP (where HIV prevalence in the three clusters was 23.8%, 25.4% and 24.9%). Since our estimates are intended to provide inference on the relationship between prevalent HIV and SES among women of reproductive age in the WCP and FSP, we weighted our sample by the population of women of reproductive age in each province. We estimated that in the year the survey started (2007), there were 8 15 465 and 1 574 682 women of reproductive age in FSP and WCP, respectively. These figures were used to derive our probability weights. Participants provided written informed consent.

Results

We had a total of 1906 study participants, 42% of whom were from WCP. The overall median age was 25 years (IQR: 21–30). The median age was 26 years (IQR: 22–31) for study participants from WCP and 24 years (IQR: 21–30) for those from FSP (P<0.001). The proportion of women who had completed secondary education, those with tertiary education and those in employment was significantly higher in the WCP than in FSP (table 1). Other sociodemographic characteristics of study participants are shown in table 1. There was a weak-to-moderate albeit significant correlation between our different measures of SES that varied by province; years of formal education versus wealth quintile (Spearman’s rho (r)=0.329; P<0.001 for WCP and r=0.583; P<0.001 for FSP); years of formal education versus employment (r=0.239; P<0.001 for WCP and r=0.017; P=0.576 for FSP); wealth quintile versus employment (r=0.353; P<0.001 for WCP and r=0.049; P=0.105).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants

| Variable | WCP, n/N (%) |

FSP, n/N (%) |

P value | Both WCP and FSP, n/N (%) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Never married | 395/802 (49.2) | 547/1104 (49.6) | 0.899 | 942/1906 (50.0) |

| Currently married | 305/802 (38.0) | 318/1104 (28.8) | <0.001 | 623/1906 (33.1) |

| Divorced | 11/802 (1.4) | 11/1104 (1.0) | 0.449 | 22/1906 (1.2) |

| Separated | 13/802 (1.6) | 56/1104 (5.1) | <0.001 | 69/1906 (3.7) |

| Widowed | 7/802 (0.9) | 35/1104 (3.2) | 0.001 | 42/1906 (2.2) |

| Married/cohabited before but current status unrecorded | 71/802 (8.9) | 137/1104 (12.4) | 0.014 | 208/1906 (10.9) |

| Highest educational level | ||||

| Primary | 92/799 (11.5) | 171/1091 (15.7) | 0.010 | 263/1890 (13.9) |

| Secondary (any grade) | 593/799 (74.2) | 866/1091 (79.4) | 0.008 | 1459/1890 (77.2) |

| Finished secondary school | 259/799 (32.5) | 262/1091 (24.0) | <0.001 | 521/1890 (27.6) |

| Tertiary | 114/799 (14.3) | 54/1091 (4.9) | <0.001 | 168/1890 (8.9) |

| Employed | 245/801 (30.6) | 131/1104 (11.9) | <0.001 | 376/1905 (19.7) |

| Wealth quintile* | ||||

| Lowest quintile (poorest) | 157/784 (20.0) | 218/1087 (20.0) | 0.987 | 375/1871 (20.0) |

| Second lowest quintile | 157/784 (20.0) | 217/1087 (20.0) | 0.974 | 374/1871 (20.0) |

| Middle quintile | 167/784 (21.3) | 218/1087 (20.0) | 0.511 | 385/1871 (20.6) |

| Second highest quintile | 159/784 (20.3) | 219/1087 (20.2) | 0.944 | 378/1871 (20.2) |

| Highest quintile (wealthiest) | 144/784 (18.4) | 215/1087 (19.8) | 0.444 | 359/1871 (19.2) |

| Setting | ||||

| Urban formal | 455/802 (56.7) | NA | NA | NA |

| Urban informal | 347/802 (43.3) | 520/1104 (47.1) | 0.097 | 867/1906 (45.5) |

| Rural formal | NA | 584/1104 (52.9) | NA | NA |

The two-sample test of equality of proportions test statistic was used for comparison of sample substrata between WCP and FSP and to generate P values.

*Household wealth quintiles were generated separately for each province using data for the specified province only.

FSP, Free State Province; n/N (%), proportion and percentage; NA, not applicable; WCP, Western Cape Province.

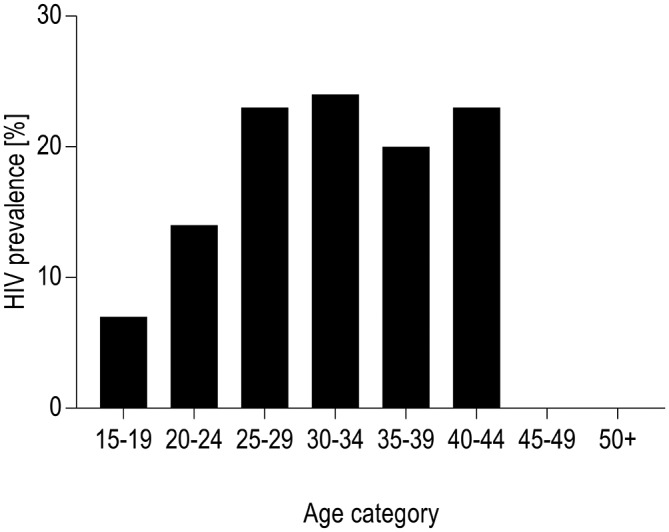

Overall HIV prevalence was 17.2%, did not significantly differ by province but varied markedly by age (figure 1) and household wealth quintile (figure 2 and table 2). Unlike in the FSP where women in the lowest household wealth quintile had the highest HIV prevalence, in WCP women in the second lowest household wealth quintile had the highest HIV prevalence. In both provinces, women in the highest household wealth quintile had the lowest HIV prevalence (figure 2). There was a significant negative trend between prevalent HIV infection and wealth quintile in both the WCP (P value for trend <0.001) and the FSP (P value for χ2 for trend=0.025). The differences in risk of prevalent HIV by marital status were largely explained by differences in sociodemographic variables such as age and years of formal schooling. Women who had never married had the highest number of years of formal schooling followed by those who were currently married, than those who were separated or widowed, with those who were divorced having the least. The median age of women who had never married was 22 years, whereas that for divorced women was 34 years.

Figure 1.

HIV prevalence by age. Data were derived from the Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission of HIV, Effectiveness in Africa and, Research and Linkages to HIV Care survey (PEARL study).23–28 There were only three study participants aged 45–49 years and one aged ≥50 years.

Figure 2.

HIV prevalence by household wealth quintiles. Data were derived from the Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission of HIV, Effectiveness in Africa and, Research and Linkages to HIV Care survey (PEARL study).23–28 FSP, study participants from the Free State Province; WCP, study participants from the Western Cape Province. Both=data for both WCP and FSP. Household wealth quintiles were generated separately for each province using data for the specified province only. The wider CI for WCP than FSP is due to clustering, as described in text. Furthermore, note that WCP had larger probability weights, used in weighting of the survey-derived data than FSP, as described in text.

Table 2.

HIV prevalence by demographic characteristics and province

| Variable | WCP, n/N (%; 95% CI) | FSP, n/N (%; 95% CI) | P value | WCP and FSP, n/N (%; 95% CI) |

| N | 108/802 (13.5%; 0% to 37.3%) | 270/1104 (24.5%; 23.3% to 25.7%) | 0.270 | 378/1906 (17.2%; 1.9% to 32.6%) |

| Age category (years) | ||||

| 15–19 | 7/101 (6.9%; 0% to 24.2%) | 17/186 (9.1%; 3.3% to 15.0%) | 0.753 | 24/287 (7.8%; 0% to 18.2%) |

| 20–24 | 25/226 (11.1%; 0% to 34.4%) | 68/363 (18.7%; 10.5% to 27.0%) | 0.438 | 93/589 (14.0%; 0% to 28.4%) |

| 25–29 | 33/178 (18.5%; 0% to 59.1%) | 77/244 (31.6%; 28.2% to 34.9%) | 0.425 | 110/422 (23.0%; 0% to 50.0%) |

| 30–34 | 20/124 (16.1%; 0% to 34.8%) | 60/141 (42.6%; 30.9% to 54.2%) | 0.029 | 80/265 (24.0%; 8.6% to 39.5%) |

| 35–39 | 12/88 (13.6%; 0% to 36.3%) | 35/102 (34.3%; 27.5% to 41.1%) | 0.073 | 47/190 (20.0%; 1.2% to 38.6%) |

| 40–44 | 3/21 (14.3%; 0% to 47.5%) | 12/30 (40.0%; 31.5% to 48.5%) | 0.106 | 15/51 (23.3%; 1.1% to 45.5%) |

| 45–49 | – | 0/3 (0; –) | – | – |

| ≥50 | 0/1 (0; –) | – | – | – |

| Marital status | ||||

| Never married | 57/395 (14.4%; 0% to 37.7%) | 105/547 (19.2%; 12.5% to 25.8%) | 0.614 | 162/942 (16.1%; 1.2% to 30.9%) |

| Currently married | 36/305 (11.8%; 0% to 37.7%) | 78/318 (24.5%; 16.4% to 32.7%) | 0.263 | 114/623 (15.4%; 0% to 34.9%) |

| Divorced/separated/ widowed |

4/31 (12.9%; 0% to 44.8%) | 50/102 (49.0%; 35.2% to 62.9%) | 0.045 | 54/133 (32.9%; 6.8% to 59.0%) |

| Married/cohabited before but current status unrecorded | 11/71 (15.5%; 3.0% to 28.0%) | 37/137 (27.0%; 20.9% to 33.1%) | 0.083 | 48/208 (20.3%; 13.0% to 27.7%) |

| Highest educational level | ||||

| Primary | 13/92 (14.1%; 1.1% to 27.2%) | 52/171 (30.4%; 24.5% to 36.3%) | 0.034 | 65/263 (20.8%; 11.9% to 29.8%) |

| Secondary (any grade) | 86/593 (14.5%; 0% to 38.5%) | 208/866 (24.0%; 22.7% to 25.3%) | 0.333 | 294/1459 (17.9%; 3.2% to 32.5%) |

| Finished secondary school | 13/145 (9.0%; 0.0% to 25.1%) | 37/208 (17.8%; 14.3% to 21.3%) | 0.214 | 50/353 (12.1%; 2.3% to 21.8%) |

| Tertiary | 9/114 (7.9%; 0% to 34.3%) | 8/54 (14.8%; 0% to 29.8%) | 0.561 | 17/168 (8.9%; 0% to 32.1%) |

| Employed | ||||

| Yes | 28/245 (11.4%; 0.0% to 38.3%) | 37/131 (28.2%; 25.1% to 31.4%) | 0.159 | 65/376 (14.2%; 0.0% to 37.8%) |

| No | 80/556 (14.4%; 0.0% to 36.1%) | 233/973 (23.9%; 22.4% to 25.5%) | 0.290 | 313/1529 (18.2%; 6.0% to 30.4%) |

| Wealth quintile* | ||||

| Lowest quintile (poorest) |

29/157 (18.5%; 10.7% to 26.2%) | 66/218 (30.3%; 24.4% to 36.1%) | 0.028 | 95/375 (22.5%; 18.2% to 26.8%) |

| Second lowest quintile | 38/157 (24.2%; 6.1% to 42.3%) | 55/217 (25.3%; 23.2% to 27.5%) | 0.871 | 93/374 (24.6%; 13.0% to 36.2%) |

| Middle quintile | 20/167 (12.0%; 0.0% to 35.4%) | 50/218 (22.9%; 17.1% to 28.8%) | 0.276 | 70/385 (15.6%; 0.0% to 31.5%) |

| Second highest quintile | 12/159 (7.5%; 0% to 26.2%) | 53/219 (24.2%; 21.5% to 26.9%) | 0.070 | 65/378 (13.2%; 0.0% to 28.5%) |

| Highest quintile (wealthiest) |

5/144 (3.5%; 0% to 14.8%) | 44/215 (20.5%; 6.5% to 34.4%) | 0.059 | 49/359 (13.6%; 0% to 24.0%) |

| Setting | ||||

| Urban formal | 18/455 (4.0%; 0% to 9.6%) | NA | NA | NA |

| Urban informal | 90/347 (25.9%; 21.4% to 30.9%) | 124/520 (23.8%; 20.2% to 27.7%) | <0.001 | 214/867 (25.2%; 23.3% to 27.1%) |

| Rural formal | NA | 146/584 (25.0%; 24.6% to 25.4%) | NA | NA |

*Household wealth quintiles were generated separately for each province using data for the specified province only, without weighting. The two-sample test of equality of proportions test statistic for survey data was used to generate P values. This test statistic involves use of the ‘lincom’ command in STATA and takes consideration of study design, that is, the two-stage stratified cluster random sampling and design weights, where appropriate, to generate point estimates, their CIs and P values. The wider CI for WCP than FSP is due to clustering, as described in text. Furthermore, please note that WCP had larger probability weights, used in weighting of the survey-derived data than FSP, as described in text.

–, insufficient data for generation of estimates; differences in totals is due to missing data; %, prevalence of HIV adjusted for design effect; FSP, Free State Province; NA, not applicable; WCP, Western Cape Province.

In our multivariate analysis, the pattern of association between prevalent HIV and SES differed by province with regards to years of formal education (table 3). In the WCP, every additional year of formal education was associated with a 10% decrease in risk of prevalent HIV which was statistically significant. The corresponding reduction in risk of prevalent HIV for women in FSP of 1% was not statistically significant. There was no significant association between employment and prevalent HIV in either province. In general, women in higher household wealth quintiles were at lower risk of prevalent HIV. Of note is that women in the second lowest quintile in WCP, but not in FSP, were at highest risk of prevalent HIV. Compared with primary school in each province, the OR estimates for risk of prevalent HIV when education was used as a categorical variable was 0.82 (0.22 to 3.12) for high school level in WCP, 0.68 (0.06 to 8.23) for tertiary level in WCP, whereas this was 1.18 (0.46 to 3.08) for high school level in FSP and 0.68 (0.19 to 2.43) for tertiary level in FSP. We did not observe collinearity between our measures of SES in our multivariate model.

Table 3.

Relationship between HIV and socioeconomic status from multivariate analysis

| Variable | Western Cape Province, aOR (95% CI) | Free State Province, aOR (95% CI) |

| Age | 1.03 (0.91 to 1.17) | 1.07 (1.02 to 1.12) |

| Setting | ||

| Urban informal | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Urban formal | 0.12 (0.01 to 1.28) | NA |

| Rural formal | NA | 1.03 (0.93 to 1.14) |

| Marital status | ||

| Never married | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Currently married | 0.77 (0.33 to 1.80) | 0.98 (0.20 to 4.90) |

| Divorced | 0.76 (0.00 to 719.64) | 0.44 (0.14 to 1.40) |

| Separated | 0.51 (0.01 to 23.71) | 2.48 (0.21 to 29.71) |

| Widowed | 1.57 (0.03 to 90.49) | 4.22 (0.51 to 34.81) |

| Years of formal education | 0.90 (0.85 to 0.96) | 0.99 (0.89 to 1.11) |

| Employment (employed vs unemployed) | 1.54 (0.84 to 2.84) | 0.96 (0.71 to 1.30) |

| Wealth quintile* | ||

| Lowest quintile (poorest) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Second lowest quintile | 1.39 (0.29 to 6.56) | 0.88 (0.67 to 1.16) |

| Middle quintile | 0.90 (0.08 to 10.57) | 0.91 (0.72 to 1.16) |

| Second highest quintile | 0.77 (0.02 to 29.80) | 0.93 (0.41 to 2.08) |

| Highest quintile (wealthiest) | 0.62 (0.00 to 250.83) | 0.76 (0.16 to 3.71) |

*Household wealth quintiles were generated separately for each province using data for the specified province only. Separate regression models were run for each province using household wealth quintiles generated separately for each province. Point estimates and their CIs were adjusted for the two-stage stratified cluster random sampling and design weights.

aOR, adjusted OR; NA, not applicable.

Discussion

The relationship between prevalent HIV infection and SES varied by province and by measure of SES in our multivariate analysis. We observed a substantive and significant negative association between prevalent HIV infection and number of years of formal education in women of reproductive age in the WCP, but not in the FSP. In both provinces, we observed a negative trend between prevalent HIV infection and household wealth quintile. There was no significant association between prevalent HIV infection and employment status in each province.

Similar to our finding in the WCP, Bärnighausen et al reported that every one additional year of formal education reduces the hazard of acquiring HIV by 7% (P=0.017) in a 2003–2004 longitudinal study in the KwaZulu Natal Province of SA.2 A similar negative association between years of formal education and prevalent HIV infection in SA was reported by Johnson et al 35 who used data from multiple nationally representative annual surveys over a period of 8 years (1998–2005) in women aged between 15 and 24 years attending antenatal clinics. From literature, women with higher educational attainment are more likely to have better knowledge of HIV prevention, are more likely to seek or receive healthcare, more likely to negotiate for safe sex and are less likely to use alcohol when having sex: all factors that reduce risk of HIV transmission.36–38 We could not explain why the magnitude of the relationship between prevalent HIV infection and years of formal education differed markedly by province. However, a systematic review on the association between SES and HIV among women in SSA evaluated 36 studies and found no association in 15 studies, a direct association in 12 studies, an inverse association in 8 studies and a mixed association in 1 study.3 Notably, most studies showing insignificant, no association or positive association between educational attainment and prevalent HIV infection were predominantly conducted prior to 1996 when the HIV epidemic had not matured in most settings in Africa.13

Similar to our finding in WCP whereby women in the second lowest household wealth quintile had the highest risk of prevalent HIV infection, Bärnighausen et al demonstrated that household members in the middle 40% of relative wealth had 72% higher hazard of HIV acquisition than the poorest 40% of households (P=0.012).2 Using data from a 2008 SA National Survey, Wabiri et al 39 demonstrated a negative association between prevalent HIV infection and wealth, similar to our general finding in both provinces. Wabiri et al showed that HIV prevalence is highest in individuals in the poorest tertile of socioeconomic index (20.8%) when compared with the middle (15.9%) and upper tertile (4.6%) (P<0.001). More recently in 2017,22 Steinert et al showed that worse relative household poverty is associated with a higher likelihood of HIV among socioeconomically deprived individuals in the KwaZulu Natal Province of SA. Speculative reasons for the increased risk of HIV among women in lower quintiles, obtained from studies similar to ours, is that these women are more likely to have earlier sexual debut, earlier marriage and risky sexual behaviours including transactional sex and reduced ability to negotiate safe sex due to economic dependence,36–38 factors which increases risk of HIV transmission.

Our lack of clear or significant association between employment status and prevalent HIV infection is largely explained by our limited power to answer this research question given less than 20% of our study participants were employed. Furthermore, our binary classification was too general to better distinguish or discriminate forms of employment associated with elevated risk of HIV transmission such as commercial sex work. We had limited data on type of employment and no data on circulatory migration, both of which are key determinants of HIV among women in SA. High and rising unemployment and social inequalities in SA leave some groups, especially poor women living around mines, extremely vulnerable to risky sexual practices such as transactional sex.40

One of the strengths of our study is that the sampling methodology and questionnaire instrument is similar to that widely used in DHS which enable cheap conduct of a similar study using secondary data and easy comparison of our findings with those widely available in literature that use a similar methodology on a comparable population. Our study uses three measures of SES which is advantageous because different measures of SES perform differently in relation to health outcomes in settings with widespread poverty and wide income inequality like SA which has one of the highest Gini coefficient in the world.3

Our study had various limitations. Observational studies are susceptible to confounding and all known and unknown confounding may not be fully adjusted for during analysis,17 particularly when dealing with latent variables such as proxy variables for SES and secondary data that have limited variables collected for a different set of research questions. For example, we did not have data on race and HIV status of partners of study participants. We appreciate that race is an important proxy variable for SES in epidemiological research in this setting. The study setting and population for the primary study were generally of lower SES. Given our analysis uses multiple measures of SES, we believe that most of the differences that would otherwise be observable by race, which usually proxy SES, are captured through the measures of SES that we present. The demographic profile at the time of conduct of the study showed that 99% and 80% of women in the FSP and WCP, respectively, were black African. The rest were mostly of mixed race origin. Thus, we doubt given this profile and our explanatory variables that race will explain any significant residual variability in prevalence of HIV infection attributable to race but not explainable by the measures of SES that we used. Household wealth indices based on household assets may not reflect women’s true financial status or access to funds in households in settings like ours that have widespread gender inequality. Thus, better measurement approaches are required that reflect the economic standing of women especially in settings with widespread gender inequality41 and gender-based violence. Finally, cross-sectional studies do not establish temporal or causal relationships but only depict associations.2 17

Regarding generalisability, our differing relationship between SES and prevalent HIV infection in two different, although contiguous, provinces in the same country by measure of SES, coupled with the mixed association between SES and prevalent HIV infection observed in systematic reviews across and within settings in SSA supports our contention that this relationship not only differs across countries but also within and between regions within countries in other SSA settings with similar HIV burden, maturity of the HIV epidemic and sociodemographic characteristics. This observation emphasises the need for research in different settings to determine or track the association between SES and prevalent HIV infection in those settings.

In summary, the association between prevalent HIV infection and SES differed by province and by measure of SES. In general, we report a negative association between relative wealth and prevalent HIV infection in women of reproductive age in both the FSP and the WCP, but a negative strong and significant association between prevalent HIV infection and number of years of formal education in the WCP but not in the FSP. There was no significant association between employment status and prevalent HIV infection. Our findings underscore the disproportionately higher burden of prevalent HIV infection, which was differential by province and measure of SES, among poorer and lowly or least educated SA women in these provinces. Our findings suggest the need for re-evaluation of whether current HIV prevention efforts meet needs of the least educated and the poorest women in each of these SA provinces, and may be a pointer to the need for additional and or tailored strategies in these women by the national HIV/AIDS control programme.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the excellent work of the South African component of the PEARL study team that was based at the University of Cape Town for collecting the data that we analysed for this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: Both authors conceived and designed the project, reviewed analysis and interpretation of the data, reviewed/revised manuscript for important intellectual content and approved final version for publication. EWB led analysis of the data and drafted the article.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: University of Cape Town Human Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at with the doi:10.5061/dryad.87hr5.

References

- 1. Unaids U. Fact sheet - Latest statistics on the status of the AIDS epidemic. 2016. http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet (accessed 17 May 2017).

- 2. Bärnighausen T, Hosegood V, Timaeus IM, et al. The socioeconomic determinants of HIV incidence: evidence from a longitudinal, population-based study in rural South Africa. AIDS 2007;21:S29–38. 10.1097/01.aids.0000300533.59483.95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wojcicki JM. Socioeconomic status as a risk factor for HIV infection in women in East, Central and Southern Africa: a systematic review. J Biosoc Sci 2005;37:1–36. 10.1017/S0021932004006534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Adler NE, Boyce T, Chesney MA, et al. Socioeconomic status and health. The challenge of the gradient. Am Psychol 1994;49:15–24. 10.1037/0003-066X.49.1.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Parkhurst JO. Understanding the correlations between wealth, poverty and human immunodeficiency virus infection in African countries. Bull World Health Organ 2010;88:519–26. 10.2471/BLT.09.070185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hargreaves JR, Bonell CP, Boler T, et al. Systematic review exploring time trends in the association between educational attainment and risk of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS 2008;22:403–14. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f2aac3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Michelo C, Sandøy IF, Fylkesnes K. Marked HIV prevalence declines in higher educated young people: evidence from population-based surveys (1995-2003) in Zambia. AIDS 2006;20:1031–8. 10.1097/01.aids.0000222076.91114.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Walque D. How does the impact of an HIV/AIDS information campaign vary with educational attainment? Evidence from rural Uganda. J Dev Econ 2007;84:686–714. 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2006.12.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mmbaga EJ, Hussain A, Leyna GH, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for HIV-1 infection in rural Kilimanjaro region of Tanzania: implications for prevention and treatment. BMC Public Health 2007;7:58 10.1186/1471-2458-7-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mmbaga EJ, Leyna GH, Mnyika KS, et al. Education attainment and the risk of HIV-1 infections in rural Kilimanjaro Region of Tanzania, 1991-2005: a reversed association. Sex Transm Dis 2007;34:947–53. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31813e0c15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kilian AH, Gregson S, Ndyanabangi B, et al. Reductions in risk behaviour provide the most consistent explanation for declining HIV-1 prevalence in Uganda. AIDS 1999;13:391–8. 10.1097/00002030-199902250-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gregson S, Garnett GP, Nyamukapa CA, et al. HIV decline associated with behavior change in eastern Zimbabwe. Science 2006;311:664–6. 10.1126/science.1121054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hargreaves JR, Glynn JR. Educational attainment and HIV-1 infection in developing countries: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health 2002;7:489–98. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00889.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen L, Jha P, Stirling B, et al. Sexual risk factors for HIV infection in early and advanced HIV epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic overview of 68 epidemiological studies. PLoS One 2007;2:e1001 10.1371/journal.pone.0001001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Magadi M, Desta M. A multilevel analysis of the determinants and cross-national variations of HIV seropositivity in sub-Saharan Africa: evidence from the DHS. Health Place 2011;17:1067–83. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dallabetta GA, Miotti PG, Chiphangwi JD, et al. High socioeconomic status is a risk factor for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection but not for sexually transmitted diseases in women in Malawi: implications for HIV-1 control. J Infect Dis 1993;167:36–42. 10.1093/infdis/167.1.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Quigley M, Munguti K, Grosskurth H, et al. Sexual behaviour patterns and other risk factors for HIV infection in rural Tanzania: a case-control study. AIDS 1997;11:237–48. 10.1097/00002030-199702000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Leclerc-Madlala S. Transactional Sex and the Pursuit of Modernity. Soc Dyn 2003;29:213–33. 10.1080/02533950308628681 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hargreaves J, Howe L, Slaymaker E. P2-515 Investigating Victoria’s inverse equity hypothesis: the changing social epidemiology of HIV infection in Tanzania. J Epidemiol Community Health 2011;65:A363 10.1136/jech.2011.142976m.42 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hargreaves JR, Morison LA, Kim JC, et al. The association between school attendance, HIV infection and sexual behaviour among young people in rural South Africa. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008;62:113–9. 10.1136/jech.2006.053827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jukes M, Simmons S, Bundy D. Education and vulnerability: the role of schools in protecting young women and girls from HIV in southern Africa. AIDS 2008;22:S41–56. 10.1097/01.aids.0000341776.71253.04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Steinert JI, Cluver L, Melendez-Torres GJ, et al. Relationships between poverty and AIDS Illness in South Africa: an investigation of urban and rural households in KwaZulu-Natal. Glob Public Health 2017;12:1183–99. 10.1080/17441692.2016.1187191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stinson K, Boulle A, Smith PJ, et al. Coverage of the prevention of mother-to-child transmission programme in the Western Cape, South Africa using cord blood surveillance. JAIDS J Acquired Immune Defic Syndromes 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stringer EM, Ekouevi DK, Coetzee D, et al. Coverage of nevirapine-based services to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission in 4 African countries. JAMA 2010;304:293–302. 10.1001/jama.2010.990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stringer JS, Stinson K, Tih PM, et al. Measuring coverage in MNCH: population HIV-free survival among children under two years of age in four African countries. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001424 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ekouevi DK, Stringer E, Coetzee D, et al. Health facility characteristics and their relationship to coverage of PMTCT of HIV services across four African countries: the PEARL study. PLoS One 2012;7:e29823 10.1371/journal.pone.0029823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Coffie PA, Kanhon SK, Touré H, et al. Nevirapine for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: a nation-wide coverage survey in Côte d’Ivoire. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011;57:S3–8. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31821ea539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stringer EM, Chi BH, Chintu N, et al. Monitoring effectiveness of programmes to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission in lower-income countries. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86:57–62. 10.2471/BLT.07.043117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Department of Health (South Africa). National Antenatal Sentinel HIV and Syphilis Prevalence Survey in South Africa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shisana O. South African national HIV prevalence, incidence, behaviour and communication survey, 2008: a turning tide among teenagers?. HSRC Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rutstein SO, Johnson K. The DHS wealth index. DHS comparative reports no. 6. Calverton: ORC Macro, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Filmer D, Pritchett LH. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data–or tears: an application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography 2001;38:115–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Corsi DJ, Neuman M, Finlay JE, et al. Demographic and health surveys: a profile. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41:1602–13. 10.1093/ije/dys184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. StataCorp L P College Station. Stata version 13.1. STATA. 2013. http://www.stata.com

- 35. Johnson LF, Dorrington RE, Bradshaw D, et al. The effect of educational attainment and other factors on HIV risk in South African women: results from antenatal surveillance, 2000-2005. AIDS 2009;23:1583–8. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832d407e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Poverty GS, Insecurity F. HIV Vulnerability and the Impacts of AIDS in sub‐Saharan Africa. IDS Bulletin 2008;39:10–18. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Masanjala W. The poverty-HIV/AIDS nexus in Africa: a livelihood approach. Soc Sci Med 2007;64:1032–41. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lachaud JP. HIV prevalence and poverty in Africa: micro- and macro-econometric evidences applied to Burkina Faso. J Health Econ 2007;26:483–504. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wabiri N, Taffa N. Socio-economic inequality and HIV in South Africa. BMC Public Health 2013;13:1037 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hunter M. The changing political economy of sex in South Africa: the significance of unemployment and inequalities to the scale of the AIDS pandemic. Soc Sci Med 2007;64:689–700. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rodrigo C, Rajapakse S. HIV, poverty and women. Int Health 2010;2:9–16. 10.1016/j.inhe.2009.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.