Abstract

Objective

To assess the use of driving-impairing medicines (DIM) in the general population with special reference to length of use and concomitant use.

Design

Population-based registry study.

Setting

The year 2015 granted medicines consumption data recorded in the Castile and León (Spain) medicine dispensation registry was consulted.

Participants

Medicines and DIM consumers from a Spanish population (Castile and León: 2.4 million inhabitants).

Exposure

Medicines and DIM consumption. Patterns of use by age and gender based on the length of use (acute: 1–7 days, subacute: 8–29 days and chronic use: ≥30 days) were of interest. Estimations regarding the distribution of licensed drivers by age and gender were employed to determine the patterns of use of DIM.

Results

DIM were consumed by 34.4% (95% CI 34.3% to 34.5%) of the general population in 2015, more commonly with regularity (chronic use: 22.5% vs acute use: 5.3%) and more frequently by the elderly. On average, 2.3 DIM per person were dispensed, particularly to chronic users (2.8 DIM per person). Age and gender distribution differences were observed between the Castile and León medicine dispensation registry data and the drivers’ license census data. Of all DIM dispensed, 83.8% were in the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical code group nervous system medicines (N), which were prescribed to 29.2% of the population.

Conclusions

The use of DIM was frequent in the general population. Chronic use was common, but acute and subacute use should also be considered. This finding highlights the need to make patients, health professionals, health providers, medicine regulatory agencies and policy-makers at large aware of the role DIM play in traffic safety.

Keywords: drug prescription; drug utilization; risk assessment; accident, traffic; automobile driving; driving-impairing medicines

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study explores the consumption of all driving-impairing medicines (DIM) and patterns of use by age and gender corresponding to a European population.

This highlights the need to make patients, health professionals, health providers, medicine regulatory agencies and policy-makers at large aware of the role of DIM in traffic safety.

The information provided covers all dispensed medicines by the public health system in Spain but does not cover hospital-dispensed medications or over-the-counter medicines, a portion of which may be DIM. Furthermore, no information is available on alcohol use or when the medicines were taken in relation to driving.

Background

Driving a motor vehicle is a multifaceted task and requires appropriate cognitive and psychomotor skills (eg, alertness, concentration, reaction time and visual acuity).1 2 Medicines can adversely affect these driving-related skills and, consequently be a hazard to traffic safety.3–5 There is increasing awareness that implementation of appropriate measures to limit the consumption of alcohol and other substances (‘illicit’ drugs and medicines) while driving may have an impact on road accident occurrences.6 Nevertheless, to date, it is unknown how frequent the consumption of driving-impairing medicines (DIM) in the general population is, or how frequently several of these drugs are consumed concomitantly.7

Conversely, most developed countries perform toxicological analyses on road accident casualties and fatalities, and the presence of illicit drugs and medicines (either used legally or illegally) are detected.8 9 On-road tests (at random or on target populations) are used ever more frequently worldwide: the on-site screening devices detect some groups of illicit drugs and certain medicines in saliva (oral fluid), with confirmation analyses being performed later.8 9 In other countries, blood analyses10 are performed, rather than screening of saliva. The information from these sources (data on casualties/fatalities and on-road test data) gives only a partial vision of the problem regarding medicines and driving.11

However, medicine regulatory agencies do attempt to provide appropriate information to the public concerning the problem: in the European Union, the summary of product characteristics and the package leaflets contain information on medicines that ‘affect the ability to drive and to use machines’.12 13 Furthermore, there have been several attempts to categorise the effects of medicines on driving14–16 and several countries, such as France17 and Spain,18 have introduced specific mandatory pictograms or ancillary warning labels, as in the Netherlands19 and Australia.20

The Spanish Law of 2007 (Royal Decree 1345/2007)18 established the rule that newly authorised medicines that may negatively affect fitness to drive or to handle dangerous machinery should include a warning symbol (pictogram) on the outside of the packaging. Since 2011, all medicines that could possibly affect fitness to drive and are commercially available in Spain have this pictogram on the packaging.21 As of January 2016, a total of 2013 medicinal drugs permitted in Spain had been reviewed, of which 402 (20%) included the pictogram on medicines and driving on the packaging.22 This pictogram is well regarded by the population.23

We have considered these medicines with the pictogram ‘medicines and driving’ on the packaging in Spain as DIM or, to be more exact, potentially impairing medicines on driving. In 2016, a national consensus on medicines and driving was reached in Spain to determine the extent of the population taking DIM as a priority and to decipher patterns of use for these drugs.24 This did not apply only to motor vehicle drivers and professional drivers but also to the population at large, as well as to all road users, including pedestrians and the ever more common cyclists. Thus, the presence of illicit drugs and medicines was also frequently found in pedestrians involved in fatal road accidents.25

The detection of some medicines in on-road tests has been the object of awareness raising in public and health professionals, as well as the subject of campaigns to inform the general public, as in the UK.26 In some countries, for instance, the UK,27 Spain28 or Norway,29 on-road positive cases to medicines are not fined if they were used according to a physician’s prescription. Again, it is necessary that the consumption of DIM and their patterns of use should be known in detail, given that there is a shortage of information about this.

Fitness to drive evaluations has been applied in most developed countries,30 31 although the procedures differ markedly. Across the European Union, there is a minimum common regulation under Council Directive 439/EEC.30 Within the context of a fitness to drive evaluation, an issue to be considered is medication use (prescribed and over-the-counter) by the driver, although this should always be assessed under the complex relationship between disease and medication, particularly among aged people who frequently suffer from several diseases and are polymedicated.1 14–16

Consequently, the aim of our study was to explore the use of DIM by the general population. The consumption of medicines with the pictogram ‘medicines and driving’ was assessed on the basis of our dispensation registry, focusing on concomitant use of these drugs and on their length of use. In addition, estimations were compared with the drivers’ license census to determine the patterns of use among drivers.

Methods

Study population: CONCYLIA database

Access was provided to the CONCYLIA database to assess the dispensation of granted medicines by the Spanish public health system in Castile and León during 2015.32

Basically, the CONCYLIA database includes information on all medicine dispensations by the public health system, except those dispensed at hospitals, medical prescriptions dispensed through private medicine clinics and those that do not require a medical prescription (‘over-the-counter’ medications).

We assessed medicine dispensation per person using the patient identification number; that is, for each person, any dispensation during 2015 was identified (eg, medicinal product, number of doses and data of dispensation). For data protection, the final database provided by the health system was anonymised, and no personal identification was included.

Target population

The population distribution covered by the public health system and the population distribution according to the population census matched well: Castile and León had a population of 2 428 901 in December 2015,33 and 2 376 717 were covered by the public health system at that time (97.85% of the total).34

The current target population of the study was the general population at large. However, not all persons had a motor vehicle license or drove motor vehicles. Due to the lack of information on driving recorded in the CONCYLIA database, weighting was performed to adjust consumption of DIM of the general population to licensed drivers by age and gender based on the Castile and León drivers’ license census data up to December 2015.35 Therefore, the results are presented in regard to the general population and/or as estimates of the driver population based on weighting to the drivers’ license census data (table 1).

Table 1.

Data on consumption of medicines according to the CONCYLIA database and drivers’ license census

| Population in Castile and León with health insurance card (December 2015) | Drivers’ license census (December 2015) | All medicines % (95% CI) |

Medicines with the pictogram ‘medicines and driving’ % (95% CI) |

Drivers using medicines with the pictogram ‘medicines and driving’ % (95% CI) |

|||

| Acute | Subacute | Chronic | |||||

| Total | 2 376 717 | 1 470 389 | 73.69 (73.63 to 73.75) | 5.31 (5.28 to 5.34) | 6.64 (6.61 to 6.67) | 22.46 (22.41 to 22.51) | 25.36 (25.29 to 25.43) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 1 168 591 | 887 357 | 68.78 (68.70 to 68.86) | 5.06 (5.02 to 5.10) | 5.58 (5.54 to 5.62) | 17.69 (17.62 to 17.76) | 26.46 (26.37 to 26.55) |

| Female | 1 208 126 | 583 032 | 78.43 (78.36 to 78.50) | 5.56 (5.52 to 5.60) | 7.66 (7.61 to 7.71) | 27.06 (26.98 to 27.14) | 23 to 69 (23.58 to 23.8) |

| Age range (Male/Female) | |||||||

| 0–4 | 45 405/42 504 | – | 76.59/74.86 | 15.61/15.31 | 2.81/2.37 | 0.52/0.43 | – |

| 5–9 | 50 925/48 078 | – | 71.22/69.60 | 6.82/7.05 | 1.57/1.34 | 2.73/1.50 | – |

| 10–14 | 49 439/47 220 | – | 67.24/65.53 | 3.47/3.86 | 1.48/1.49 | 6.92/3.12 | – |

| 15–19 | 48 620/46 904 | 9 282/5 586 | 62.49/68.16 | 3.17/4.18 | 2.88/4.71 | 7.06/5.33 | 2.50/1.69 |

| 20–24 | 54 724/53 382 | 43 294/35 387 | 53.00/67.78 | 3.48/4.77 | 3.81/6.75 | 4.51/5.87 | 9.34/11.53 |

| 25–29 | 62 787/61 247 | 55 831/50 618 | 47.83/65.06 | 3.51/5.06 | 4.15/7.36 | 4.81/7.23 | 11.09/16.24 |

| 30–34 | 75 089/71 664 | 69 810/61 387 | 46.72/66.41 | 3.51/5.27 | 4.62/7.87 | 6.02/9.44 | 13.16/19.34 |

| 35–39 | 90 372/87 031 | 86 841/75 838 | 50.20/68.35 | 3.95/5.20 | 5.25/8.40 | 7.84/12.28 | 16.38/22.56 |

| 40–44 | 92 686/89 879 | 89 294/76 277 | 54.63/69.28 | 4.10/5.27 | 5.72/8.89 | 10.12/16.23 | 19.20/25.79 |

| 45–49 | 93 082/91 643 | 90 151/74 310 | 59.23/72.04 | 4.32/5.47 | 5.99/9.55 | 12.90/20.68 | 22.48/28.95 |

| 50–54 | 93 252/90 618 | 90 450/67 282 | 66.50/77.55 | 4.87/5.83 | 6.47/9.86 | 16.37/25.63 | 26.88/30.67 |

| 55–59 | 87 280/84 212 | 85 820/56 346 | 74.43/82.71 | 5.09/5.83 | 7.04/9.60 | 20.38/31.45 | 31.96/31.37 |

| 60–64 | 72 448/69 337 | 71 450/36 255 | 82.67/87.96 | 5.57/5.98 | 7.34/9.87 | 25.65/37.38 | 38.03/27.84 |

| 65–69 | 65 430/66 777 | 62 572/23 964 | 89.09/91.10 | 5.88/5.90 | 7.97/9.69 | 31.21/43.95 | 43.09/21.37 |

| 70–74 | 56 526/61 968 | 51 161/12 390 | 93.79/94.39 | 5.86/5.55 | 8.01/9.14 | 38.05/52.02 | 46.98/13.34 |

| 75–79 | 45 154/56 939 | 35 993/5 000 | 93.34/93.00 | 5.76/4.74 | 7.89/8.21 | 44.10/58.52 | 46.04/6.28 |

| 80–84 | 44 543/62 354 | 28 304/1 941 | 95.81/95.85 | 5.41/4.21 | 7.38/7.21 | 51.24/64.90 | 40.69/2.38 |

| 85–89 | 27 547/46 335 | 14 160/429 | 99.79/98.09 | 4.98/3.66 | 7.63/6.57 | 56.91/69.24 | 35.74/0.74 |

| ≥90 | 13 282/30 034 | 2 944/22 | 99.90/98.51 | 4.59/3.39 | 8.20/6.37 | 58.92/68.08 | 15.89/0.06 |

Driving-Impairing Medicines

As mentioned above, granted medicines in Spain with the pictogram ‘medicines and driving’ were considered as DIM.

In the CONCYLIA database, based on the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical code (ATC), each one of the medicines is identified as having such a pictogram or not. This information was taken from the Spanish Medicine Agency, updated to 1 February 2016.22

Variables and ethical issues

The following variables describing the consumption of medicines and DIM in Castile and León in the year 2015 were considered: (1) Yearly frequency of all medicine use; (2) Yearly frequency of DIM use: acute (1–7 days), subacute (8–29 days) and chronic or regular use (≥30 days); (3) Yearly frequency of daily use of at least one DIM and (4) Number and means of different DIM taken within 2015.

All analyses were made considering age and gender distributions.

Ethics Review Board approval was obtained (Reference number PI 16–387, approved on 17 March 2016).

Statistical analysis

All values are given as percentages (frequencies) with a 95% CI or as the mean±SD. For comparisons, Student’s t-test was used for continuous variables and Pearson’s χ2 test for categorical variables. A two-tailed p<0.05 was considered to be significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS V.23.0.

Results

Descriptive mapping

A total of 48 858 588 medicines were dispensed in 2015. Approximately three of four people took a medicinal product in 2015, with more women than men taking the product (78.4% vs 68.8%, p<0.05), and this fraction increased with age (table 1).

One of three (34.4%, 95% CI 34.3% to 34.5%) consumed DIM in 2015, again more frequently among women (40.3% vs 28.3%, p<0.05), and this also increased with age. A majority needed to use these medicines on a regular basis (chronic use: 22.5%), while the use for a few days or weeks accounted for 5.3% and 6.6%, respectively, with similar patterns of use by age and gender (table 1).

However, if the distribution is performed with respect to the drivers’ license census, 25.4% (95% CI 25.3% to 25.43%) of people took DIM in 2015, with more men than women (26.5% vs 23.7%, p<0.05) and mostly took DIM regularly (chronic use: 15.3%, 95% CI 15.2% to 15.32%; subacute use: 5.96%, 95% CI 5.92% to 5.99%; acute use: 4.14%, 95% CI 4.11% to 4.18%).

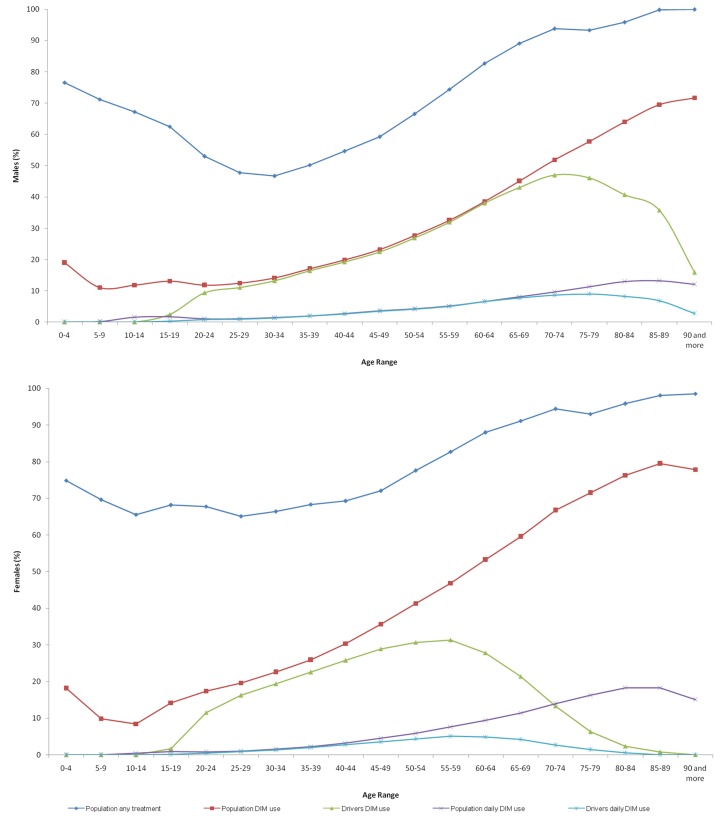

Figure 1 and table 1 show those who used DIM in 2015, their distribution by age and gender, and relation to the drivers’ license census. Age trends differed between the sexes with consumption dropping dramatically among female drivers from 60 years of age and male drivers using less DIM over 75 years of age.

Figure 1.

Frequency of medicine consumption in Castile and León in 2015. DIM, driving-impairing medicines.

At least one DIM was consumed daily by 5.6% (95% CI 5.52% to 5.58%) of people and by 3.7% (95% CI 3.67% to 3.73% of licensed drivers.

On average (table 2), each person taking DIM took 2.3 medicines (2.1 according to the drivers’ license census data). Acute and subacute consumers (97.5% and 69.1%, respectively) took only one DIM, while chronic consumers (71.5%) took two DIM or more (mean number of DIM use: 2.8). Trends between sexes were similar when the drivers’ license census data were analysed (table 2).

Table 2.

Frequency of the consumption of driving-impairing medicines (DIM)

| Frequency of use | No of DIM | Patients under treatment % (95% CI) |

Drivers under treatment % (95% CI) |

||||

| Males | Females | Total | Males | Females | Total | ||

| Acute | 1 | 97.82 (97.71 to 97.94) | 97.17 (97.05 to 97.3) | 97.48 (97.39 to 97.56) | 98.09 (97.95 to 98.22) | 97.36 (97.16 to 97.57) | 97.81 (97.69 to 97.93) |

| 2 | 2.16 (2.04 to 2.28) | 2.80 (2.67 to 2.92) | 2.50 (2.41 to 2.58) | 1.89 (1.75 to 2.03) | 2.6 (2.39 to 2.8) | 2.16 (2.04 to 2.28) | |

| ≥3 | 0.02 (0.01 to 0.03) | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.05) | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.03) | 0.02 (0.01 to 0.04) | 0.04 (0.01 to 0.06) | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.04) | |

| Mean (±SD) | 1.02 1.02 to 1.02) | 1.03 (1.03 to 1.03) | 1.03 (1.03 to 1.03) | 1.02 (1.02 to 1.02) | 1.03 (1.03 to 1.03) | 1.02 (1.02 to 1.02) | |

| Subacute | 1 | 71.59 (71.25 to 71.94) | 67.39 (67.08 to 67.69) | 69.13 (68.90 to 69.35) | 71.75 (71.36 to 72.15) | 68.59 (68.12 to 69.06) | 70.41 (70.1 to 70.71) |

| 2 | 24.71 (24.38 to 25.04) | 27.35 (27.06 to 27.63) | 26.26 (26.04to 26.47) | 24.53 (24.15 to 24.9) | 26.32 (25.87 to 26.77) | 25.29 (25 to 25.58) | |

| ≥3 | 3.69 (3.55 to 3.84) | 5.27 (5.12 to 5.41) | 4.62 (4.51 to 4.72) | 3.72 (3.56 to 3.89) | 5.09 (4.86 to 5.31) | 4.3 (4.17 to 4.44) | |

| Mean (±SD) | 1.32 (1.32 to 1.32) | 1.38 (1.38 to 1.38) | 1.36 (1.36 to 1.36) | 1.32 (1.32 to 1.32) | 1.37 (1.36 to 1.38) | 1.34 (1.34 to 1.34) | |

| Chronic | 1 | 31.36 (31.04 to 31.67) | 23.84 (23.65 to 24.05) | 26.76(26.58 to 26.93) | 30.91 (30.54 to 31.28) | 25.58 (25.12 to 26.03) | 29.07 (28.78 to 29.36) |

| 2 | 28.34 (28.03 to 28.64) | 26.96 (26.74 to 27.17) | 27.49 (27.31 to 27.67) | 28.33 (27.97 to 28.69) | 28.22 (27.75 to 28.68) | 28.29 (28 to 28.58) | |

| ≥3 | 40.31 (39.97 to 40.64) | 49.20 (48.95 to 49.44) | 45.75 (45.56 to 45.95) | 40.76 (40.36 to 41.15) | 46.21 (45.69 to 46.72) | 42.64 (42.33 to 42.95) | |

| Mean (±SD) | 2.63 (2.62 to 2.64) | 2.96 (2.95 to 2.97) | 2.83 (2.82 to 2.84) | 2.65 (2.64 to 2.66) | 2.86 (2.85 to 2.87) | 2.72 (2.71 to 2.73) | |

| Total | Mean (±SD) | 2.08 (2.07 to 2.09) | 2.39 (2.38 to 2.40) | 2.27 (2.27 to 2.27) | 2.1 (2.09 to 2.11) | 2.15 (2.14 to 2.16) | 2.12 (2.11 to 2.13) |

Types of DIM consumed

Of the 10 862 138 DIM dispensed, 9 102 052 (83.8%) belonged to the ATC classification group N (nervous system), 1 176 864 (10.8%) to group A (alimentary tract and metabolism) and 1 60 631 (1.5%) to group R (respiratory system). ATC group N medicines were prescribed to 29.2% of the population (21.3% regarding the drivers’ license census), group A medicines to 5.4% (4% for drivers) and group R medicines to 4% (2.3% for drivers) (table 3).

Table 3.

Frequency of the consumption of driving-impairing medicines by ATC group

| ATC groups | Patients under treatment % (95% CI) |

Drivers under treatment % (95% CI) |

||||

| Males | Females | Total | Males | Females | Total | |

| A | 5.3 (5.26 to 5.34) | 5.5 (5.46 to 5.54) | 5.4 (5.37 to 5.43) | 5.13 (5.08 to 5.17) | 2.24 (2.21 to 2.28) | 3.98 (3.95 to 4.02) |

| C | 0.36 (0.35 to 0.37) | 0.26 (0.25 to 0.26) | 0.31 (0.3 to 0.31) | 0.32 (0.31 to 0.33) | 0.04 (0.04 to 0.05) | 0.21 (0.2 to 0.22) |

| D | 0.12 (0.12 to 0.13) | 0.11 (0.1 to 0.11) | 0.11 (0.11 to 0.12) | 0.07 (0.07 to 0.08) | 0.08 (0.07 to 0.09) | 0.08 (0.07 to 0.08) |

| G | 0.6 (0.59 to 0.62) | 1 (0.99 to 1.02) | 0.81 (0.79 to 0.82) | 0.52 (0.5 to 0.53) | 0.49 (0.47 to 0.51) | 0.51 (0.49 to 0.52) |

| J | 0.02 (0.02 to 0.03) | 0.03 (0.03 to 0.04) | 0.03 (0.03 to 0.03) | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.03) | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.03) | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.03) |

| L | 0.51 (0.49 to 0.52) | 0.07 (0.06 to 0.07) | 0.28 (0.28 to 0.29) | 0.37 (0.36 to 0.38) | 0.05 (0.04 to 0.05) | 0.24 (0.23 to 0.25) |

| M | 0.7 (0.69 to 0.72) | 1.11 (1.09 to 1.13) | 0.91 (0.9 to 0.92) | 0.78 (0.76 to 0.8) | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.04) | 0.87 (0.86 to 0.89) |

| N | 22.45 (22.37 to 22.52) | 35.68 (35.6 to 35.77) | 29.17 (29.12 to 29.23) | 21.51 (21.42 to 21.6) | 21.02 (20.91 to 21.12) | 21.31 (21.25 to 21.38) |

| P | 0.08 (0.07 to 0.08) | 0.24 (0.23 to 0.25) | 0.16 (0.15 to 0.16) | 0.08 (0.07 to 0.09) | 0.19 (0.18 to 0.2) | 0.12 (0.12 to 0.13) |

| R | 3.62 (3.59 to 3.65) | 4.38 (4.34 to 4.41) | 4 (3.98 to 4.03) | 2.51 (2.48 to 2.54) | 1.98 (1.94 to 2.02) | 2.3 (2.27 to 2.32) |

| S | 0.41 (0.4 to 0.42) | 0.42 (0.41 to 0.43) | 0.41 (0.41 to 0.42) | 0.33 (0.32 to 0.35) | 0.1 (0.09 to 0.1) | 0.24 (0.23 to 0.25) |

| V | 0 (0 to 0) | 0 (0 to 0) | 0 (0 to 0) | 0 (0 to 0) | 0 (0 to 0) | 0 (0 to 0) |

A, alimentary tract and metabolism; ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System; C, cardiovascular system; D, dermatologicals; G, genitourinary system and sex hormones; J, antiinfectives for systemic use; L, antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents; M, musculoskeletal system; N, nervous system; P, antiparasitic products, insecticides and repellents; R, respiratory system; S, sensory organs; V, various.

Interestingly, ATC groups N, A and R were more frequently prescribed to women than men, all people considered. When considering licensed drivers, the trends showed no differences. Table 4 shows DIM used for several days or weeks and chronically.

Table 4.

Frequency of the consumption of driving-impairing medicines A, N and R ATC group

| ATC group | Frequency of use | Patients under treatment % (95% CI) |

Drivers under treatment % (95% CI) |

||||

| Males | Females | Total | Females | Males | Total | ||

| A | Acute | 0.68 (0.61 to 0.74) | 1.53 (1.44 to 1.62) | 1.12 (1.06 to 1.18) | 0.57 (0.5 to 0.64) | 2.22 (1.96 to 2.47) | 0.94 (0.86 to 1.02) |

| Subacute | 17.7 (17.4 to 18) | 29.63 (29.28 to 29.98) | 23.87 (23.64 to 24.11) | 17.69 (17.34 to 18.04) | 53.18 (52.32 to 54.03) | 25.62 (25.27 to 25.97) | |

| Chronic | 81.62 (81.32 to 81.93) | 68.84 (68.49 to 69.19) | 75.01 (74.77 to 75.24) | 81.74 (81.38 to 82.09) | 44.6 (43.75 to 45.46) | 73.44 (73.09 to 73.8) | |

| N | Acute | 18.06 (17.92 to 18.21) | 12.79 (12.69 to 12.89) | 14.79 (14.7 to 14.87) | 18.02 (17.85 to 18.2) | 16.55 (16.34 to 16.75) | 17.45 (17.31 to 17.58) |

| Subacute | 21.6 (21.44 to 21.76) | 18.8 (18.68 to 18.91) | 19.86 (19.76 to 19.95) | 23.53 (23.34 to 23.72) | 25.72 (25.48 to 25.97) | 24.39 (24.24 to 24.54) | |

| Chronic | 60.33 (60.15 to 60.52) | 68.41 (68.27 to 68.55) | 65.36 (65.24 to 65.47) | 58.45 (58.23 to 58.67) | 57.73 (57.45 to 58.01) | 58.17 (57.99 to 58.34) | |

| R | Acute | 71.93 (71.5 to 72.36) | 74.38 (74.01 to 74.76) | 73.29 (73.01 to 73.58) | 70.21 (69.61 to 70.81) | 78.92 (78.17 to 79.66) | 73.18 (72.71 to 73.65) |

| Subacute | 22.63 (22.24 to 23.03) | 21.93 (21.57 to 22.28) | 22.24 (21.98 to 22.5) | 23.86 (23.3 to 24.42) | 18.49 (17.78 to 19.2) | 22.03 (21.58 to 22.47) | |

| Chronic | 5.43 (5.22 to 5.65) | 3.69 (3.53 to 3.85) | 4.46 (4.33 to 4.6) | 5.93 (5.62 to 6.24) | 2.59 (2.3 to 2.88) | 4.79 (4.56 to 5.02) | |

A, alimentary tract and metabolism; ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System; N, nervous system; R, respiratory system.

Discussion

A detailed description of the consumption of DIM in the general population from Castile and León in 2015 is provided. DIM were consumed by 34.4% (95% CI 34.3% to 34.5%) of the general population and more commonly on a regular basis (22.5%). However, the use for several days (5.3%) or a few weeks (6.6%) should not be neglected. The consumption of DIM increased in line with age. Acute and subacute consumers took at least one DIM and chronic users took nearly three. Of all DIM dispensed, 83.8% belong to the ATC classification group N (nervous system), which were dispensed to 29.2% of the population. Similar trends were found regarding the distribution of licensed drivers by gender but not by age.

The DRUID project1 provides information on the prevalence of use in Europe of some types of medicines randomly detected in drivers.36 Of all positive matches (1.36%), benzodiazepines (0.9%), Z-drugs (0.12%) and opioids (0.35%) were frequently confirmed. Furthermore, there is information for other developed countries on the consumption of alcohol, illicit drugs and certain medicines by people injured/killed in road traffic accidents.8–11 The DRUID study conducted on injured (seriously injured or killed) people in nine European countries did not produce a clear picture of the use of medicines (and illicit drugs), but combined use of alcohol with medicines (and/or illicit drugs) was shown to be much more common in drivers who had accidents than in the driving population.36 Although progress has been made in understanding this social and medical problem of driving under the effects of medicines, the available data enable only a partial view of the problem, as only several groups of DIM (mainly psychotropic drugs) have been analysed in blood and oral fluid specimens from drivers. There has also been an attempt to estimate DIM consumption based on dispensed medicines7 or using driver consumption surveys.37 Our study provides a detailed overview of all DIM used by the general population, and to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first on this matter.

The combined use of DIM with alcohol is well known to have marked effects on psychomotor performance.1 5 14–16 Furthermore, the risk of being seriously injured or killed while driving with these psychoactive substances was highly increased with multiple use and the risk increased severely with combined use with alcohol.1 36 Avoiding use of alcohol is a priority for safe driving,1 6 but particularly for those who take medicines, either acutely or regularly.

One of three used DIM in 2015. Importantly, acute users represented a sizeable proportion of all drivers consuming DIM (5.3%). The effect of medications on driving is more relevant in the first days of use.38 39 Drivers consuming DIM for few days might therefore be the most affected, particularly those taking more than one medicine, and this must be taken into account. In addition, multiple daily dosing is an important factor to consider,7 40 especially for drivers over 50 years old.40

More than two DIM were dispensed (drivers and non-drivers), particularly to chronic users who took nearly three. In addition, approximately 6% of people consumed at least one DIM daily during the year 2015. Impairment of driving seems to diminish with chronic/stable DIM use,39 probably due to tolerance.41 However, clinical explorations of fitness to drive under the effects of DIM should be performed.41 Tolerance is a problem that has not been completely assessed and what occurs when more than one medicine is consumed has also not been analysed. A higher prevalence of regular and daily use of DIM are not uncommon in Spain and other developed countries. Therefore our results provide an epidemiological view of the current impact of medicine use patterns that highlight the importance of daily regimens, as well as the importance for elderly acute users.

Our results showed that several types of medicines are prescribed more often than others. ATC group N medicines were prescribed with predilection, mostly to women. This finding was corroborated by the study of Ravera et al.7 The finding of frequent DIM use was not surprising, as 20% of the granted medicines (402 of 2013) in Spain are DIM (with the pictogram ‘medicines and driving’ on the packaging). In addition, 83.8% of dispensed DIM in Castile and León were ATC group N medicines (178 of 402). In this context, mandatory pictograms and warning labels contribute to awareness of DIM consumption risks for consumer engagement,42 43 with the noticeability of these medication warnings a challenging task.44 Furthermore, there are initiatives worldwide for refining information on the risk categorisation of drugs1 14–16 45 46 that must be implemented in dispensing support tools (software)47 for a better prescription/dispensation of DIM.

Our study showed that DIM use by the population is frequent, even in young people/children, who are not motorised vehicle drivers; however, all of us are road users (pedestrians). Medicinal products authorised for use in children do not have the pictogram for medicines and driving in Spain; however, medicines that could be used by the population, including young people, include it. Although the topic of medicines and driving has focused on motorised vehicles, their use by cyclists and pedestrians25 is a field of growing interest, especially involving road accidents.

Our study was based in a region of Spain. Current information from the CONCYLIA medicines dispensation registry shows that medication use in Castile and León does not differ from other areas in Spain (as measured in Defined Daily Doses per 1000 inhabitants day)48 49 and are in line with those reported in other countries.7 Recently, Eurostat reported on medicine use in the European Union.50 In the European health interview survey, conducted between 2013 and 2015, people were asked about self-reported medicine use. Our data by gender and age range agree well with these results, although figures from the Eurostat refer to medicine use in the 2 weeks prior to the survey, and the current data were based on any medicine dispensed in 2015. Therefore, although considered with caution due to possible country variations, the figures from the present study could be generalised to other developed countries.

Our study provides detailed information on which DIM are consumed and how. We thus fulfilled the objectives of the Spanish consensus on medicines and driving reached recently. Giving clearer information about the influence of medicines on driving to sensitise health professionals and the general population on the negative effects of DIM is a priority.24 Our results stress the need to improve the communication of DIM risks, in line with recent requirements. Nevertheless, DIM risk communication is a complex clinical, methodological and epidemiological challenge, and the ‘boosters’ (warning label methods, dispensation software, information campaigns, etc) should be cautiously implemented in key steps, with the main objective to minimise road accidents. Again, detailed knowledge of the use of DIM is a priority.

This study has several limitations. The health system in Spain is public and free, and we used the data from a medicine dispensation registry, which implies that the information covers all dispensed medicines within such a system but not hospital-dispensed medications or over-the-counter medicines, several of which may not have the Spanish pictogram. Data are presented regarding the general population, not only drivers, because even pedestrians and cyclists could be involved in road traffic accidents with DIM being a possible cause.25 In the CONCYLIA database, no information on medicine use by drivers is recorded, and weighting was performed to adjust the consumption of DIM among licensed drivers by age and gender based on the Castile and León drivers’ license census data. This should be taken into account, as the distribution of drivers in other countries or regions could be different, and especially because information is not available on the extent to which drivers with a license drove vehicles. Furthermore, we do not have information on patterns of alcohol use or on driving patterns. Importantly, the effect of drugs on driver behaviour (and crash risk) depends on when the drug was taken in relation to driving. Our study showed that a high percentage of drivers are taking DIM and are frequently taking several DIM. However, we do not have information about when the drivers took the medications; for example, they may have taken them at a time when their driving was unlikely to be impaired (ie, before bed).

Conclusions

The use of DIM was frequent in the general population based on the findings of Castile and León in 2015. Chronic use (30 days or more) was common, but acute use (1–7 days) and subacute use (8–29 days) must not be overlooked because they might be the most relevant regarding DIM consumption and risks. ATC group N medicines were the most frequently prescribed.

There is a need worldwide to improve interventions in the field of medicines and driving.1 6 Interventions have been suggested for such populations as the general public (information, awareness of risks for DIM use on driving),1 45 for health professionals (eg, risk communications to the patients, categorisation systems, fitness to drive evaluation),15 16 for health provider systems (prescribing and dispensation software tools),16 47 for health authorities/medicinal regulatory agencies for improving medicinal product labelling systems and inserted patient information leaflets,23 42–44 and for road safety policy-makers.1 6 45

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: FJA conceived the study design. EG-A conducted the study. EG-A, FH-G, PC-E and FJA analysed the data, contributed to the interpretation of the results and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Redes Temáticas de Investigación Cooperativa, Red de Trastornos Adictivos, grant number RD16/0017/0006, co-funded by FEDER funds of European Union—a way to build Europe.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: CEIC Area de Salud Valladolid Este, Ethic Review Board approval was obtained (Reference number PI 16-387, approved on March 17th, 2016).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Schulze H, Schumacher M, Urmeew R, et al. Driving under the influence of drugs, alcohol and medicines in europe — findings from the DRUID project.Lisbon, Portugal emcdda: 2012. http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/thematic-papers/druid (accessed 9 Jan 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ramaekers JG. Drugs and driving research in medicinal drug development. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2017;38:319–21. 10.1016/j.tips.2017.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ravera S, van Rein N, de Gier JJ, et al. Road traffic accidents and psychotropic medication use in The Netherlands: a case-control study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2011;72:505–13. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03994.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Orriols L, Delorme B, Gadegbeku B, et al. Prescription medicines and the risk of road traffic crashes: a French registry-based study. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000366 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Berghaus G, Sticht G, Grellner W, et al. Meta-analysis of empirical studies concerning the effects of medicines and illegal drugs including pharmacokinetics on safe driving. DRUID project deliverable 1.1.2b Cologne, Germany: BAST; 2010. http://www.druid-project.eu/Druid/EN/deliverales-list/downloads/Deliverable_1_1_2_B.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=1 (accessed 17 Jul 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 6. WHO. Drug use and road safety: a policy brief. Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/249533 (accessed 9 Jan 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ravera S, Hummel SA, Stolk P, et al. The use of driving impairing medicines: a European survey. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2009;65:1139–47. 10.1007/s00228-009-0695-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gómez-Talegón T, Fierro I, González-Luque JC, et al. Prevalence of psychoactive substances, alcohol, illicit drugs, and medicines, in Spanish drivers: a roadside study. Forensic Sci Int 2012;223:106–13. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2012.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Simonsen KW, Steentoft A, Hels T, et al. Presence of psychoactive substances in oral fluid from randomly selected drivers in Denmark. Forensic Sci Int 2012;221:33–8. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2012.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bezemer KD, Smink BE, van Maanen R, et al. Prevalence of medicinal drugs in suspected impaired drivers and a comparison with the use in the general Dutch population. Forensic Sci Int 2014;241:203–11. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2014.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rudisill TM, Zhao S, Abate MA, et al. Trends in drug use among drivers killed in U.S. traffic crashes, 1999-2010. Accid Anal Prev 2014;70:178–87. 10.1016/j.aap.2014.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Council of the European communities. Council Directive 83/570/EEC of 26 October 1983 amending Directives 65/65/EEC,75/318/EEC and 75/319/EEC on the approximation of provisions laid down by law, regulation or administrative action relating to proprietary medicinal products. Oj L 1983;332:1–10 http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/1983/570/oj. [Google Scholar]

- 13. European Commission. Enterprise and Industry Directorate-GeneralA guideline on Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC). 2009. http://ec.europa.eu/health/files/eudralex/vol-2/c/smpc_guideline_rev2_en.pdf and http://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/eudralex/vol-2/index_en.htm (accessed 9 Jan 2017).

- 14. de Gier JJ, Alvarez FJ, Mercier-Guyon C. et al. Prescribing and dispensing guidelines for medicinal drugs affecting driving performance : Verster JC, Pandi-Perumal SR, Ramaekers JG, de Gier JJ. Drugs, Driving and Traffic Safety. Basel, Switzerland: Birkaeuse: Verlag AG; In Press, 2009:121–34. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gómez-Talegón T, Fierro I, Del Río MC, et al. Establishment of framework for classification/categorisation and labelling of medicinal drugs and driving. DRUID project Deliverable 4.3.1 Cologne, Germany: BAST; 2011. http://www.druid-project.eu/Druid/EN/deliverales-list/downloads/Deliverable_4_3.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=1 (accessed 17 Jul 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ravera S, Monteiro SP, de Gier JJ, et al. A European approach to categorizing medicines for fitness to drive: outcomes of the DRUID project. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2012;74:920–31. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04279.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ministère de la Santé et des Solidarités. Direction Generale de la Santé. Arrêté du 18 Juillet 2005 pris pour l’application de l’article R.5121-139 du code de la santé publique et relative à l’opposition d’un pictogramme sur le conditionnement extérieur de certain médicaments et produits. Journal Officiel de la République Française. Août 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Real Decreto 1345/2007, de 11 de octubre, por el que se regula el procedimiento de autorización, registro y condiciones de dispensación de los medicamentos de uso humano fabricados industrialmente. pp. 45652–45698. BOE de 7 de Noviembre de 2007.. http://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2007-19249 (accessed 9 Jan 2017 45652 45692). [Google Scholar]

- 19. Patrício Monteiro S. Driving-impairing Medicines and Traffic Safety: Patient’s Perspectives. PhD thesis. Groningen, The Netherlands; University of Groningen; 2014. http://www.rug.nl/research/portal/files/6563594/volledigedissertatie_1_.pdf (accessed 9 Jan 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jomaa I, Odisho M, Cheung JM, et al. Pharmacists’ perceptions and communication of risk for alertness impairing medications. Res Social Adm Pharm. In Press 2017. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.sapharm.2016.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios. Medicamentos y Conduccion http://www.aemps.gob.es/industria/etiquetado/conduccion/home.htm (accessed 9 Jul 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 22. Agencia spañola de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios. Medicamentos y Conduccion: Listados de principios activos por grupos ATC* e incorporación del pictograma de la conducción. http://www.aemps.gob.es/industria/etiquetado/conduccion/listadosPrincipios/home.htm (accessed 9 Jul 2016).

- 23. Fierro I, Gómez-Talegón T, Alvarez FJ. The Spanish pictogram on medicines and driving: the population’s comprehension of and attitudes towards its use on medication packaging. Accid Anal Prev 2013;50:1056–61. 10.1016/j.aap.2012.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Documento de consenso sobre medicamentos y conducción en España: información a la población general y papel de los profesionales sanitarios. Madrid, Spain: Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad and Ministerio del Interior 2016. http://www.msssi.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/prevPromocion/docs/Medicamentos_conduccion_DocConsenso.pdf (accessed 10 May 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 25. Instituto Nacional de Toxicología y Ciencias Forenses. Víctimas mortales en accidentes de tráfico: memoria 2016. Madrid, Spain: Ministerio de Justicia 2016. https://administraciondejusticia.gob.es/paj/PA_WebApp_SGNTJ_NPAJ/descarga/Memoria%20Trafico%20INTCF202014.pdf?idFile=00359cf9-26d5-4d33-96ea-ec9703c78470 (Accessed 9 January 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 26. GOV:UK Drugs and driving: the law. Collection Drug driving https://www.gov.uk/drug-driving-lawhttps://www.gov.uk/government/collections/drug-driving#table-of-drugs-and-limits (accessed 9 January 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 27. Department for Transport. Guidance for healthcare professionals on drug driving. London, United Kingdom: Department for Transport 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/325275/healthcare-profs-drug-driving.pdf (Accessed 9 January 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 28. Álvarez FJ, González-Luque JC, Drugs S-GM, et al. and Driving: Intervention of Health Professionals in the Treatment of Addictions. Adicciones 2015;27:161–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Norwegian Ministry of Transport and Communications. Driving under the influence of non-alcohol drugs-legal limits implemented in Norway. Oslo, Norway: Norwegian Government Security and Service Organization; 2014. https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/sd/vedlegg/brosjyrer/sd_ruspavirket_kjoring_net.pdf (accessed 9 January 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 30. Council Directive 91/439/EEC of 29 July 1991 on driving licences. Official Journal. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ES/TXT/?uri=CELEX:31991L0439 accessed 17 Jul 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Austroads. Assessing Fitness to drive for commercial and private vehicle drivers. Fifth Edition Sydney, Australia: Austroads Ltd, 2016. https://www.onlinepublications.austroads.com.au/downloads/AP-G56-16 (accesssed 17 Jul 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 32. CONCYLIA. Sistema de Información de Farmacia. Gerencia Regional de Salud de Castilla y León. Valladolid, Spain: Junta de Castilla y León. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Cifras oficiales de población de los municipios españoles:Revisión del Padrón Municipal. Madrid, Spain http://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736177011&menu=resultados&secc=1254736195458&idp=1254734710990 (accessed 15 Jun 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tarjeta Sanitaria de S. Recursos y Gestión Poblacional. Gerencia Regional de Salud. Valladolid, Spain: Junta de Castilla y León, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ministerio del Interior. Dirección General de Tráfico. Estadísticas e Indicadores. Permisos de conducción. http://www.dgt.es/es/seguridad-vial/estadisticas-e-indicadores/permisos-conduccion/ (accessed 15 June 2016).

- 36. Bernhoft IM. coordinator). Results from epidemiological research - prevalence, risk and characteristics of impaired drivers. DRUID project Deliverable 2.4.1. Cologne, Germany: BAST 2011. http://www.druid-project.eu/Druid/EN/deliverales-list/downloads/Deliverable_2_4_1.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=1 (accessed 20 Jul 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 37. Del Río MC, Alvarez FJ. Medication and fitness to drive. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2003;12:389–94. 10.1002/pds.806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Barbone F, McMahon AD, Davey PG, et al. Association of road-traffic accidents with benzodiazepine use. Lancet 1998;352:1331–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)04087-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wilhelmi BG, Cohen SP. A framework for "driving under the influence of drugs" policy for the opioid using driver. Pain Physician 2012;15:ES215–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Monárrez-Espino J, Laflamme L, Elling B, et al. Number of medications and road traffic crashes in senior Swedish drivers: a population-based matched case-control study. Inj Prev 2014;20:81–7. 10.1136/injuryprev-2013-040762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schumacher MB, Jongen S, Knoche A, et al. Effect of chronic opioid therapy on actual driving performance in non-cancer pain patients. Psychopharmacology 2017;234:989–99. 10.1007/s00213-017-4539-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Monteiro SP, Huiskes R, Van Dijk L, et al. How effective are pictograms in communicating risk about driving-impairing medicines? Traffic Inj Prev 2013;14:299–308. 10.1080/15389588.2012.710766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Emich B, van Dijk L, Monteiro SP, et al. A study comparing the effectiveness of three warning labels on the package of driving-impairing medicines. Int J Clin Pharm 2014;36:1152–9. 10.1007/s11096-014-0010-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Smyth T, Sheehan M, Siskind V, et al. Consumer perceptions of medication warnings about driving: a comparison of French and Australian labels. Traffic Inj Prev 2013;14:557–64. 10.1080/15389588.2012.729278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schulze H, Schumacher M, Urmeew R, et al. Driving Under the Influence of Drugs, Alcohol and Medicines) project. Final Report: Work performed, main results and recommendations. DRUID project Deliverable 0.1.8. Revision 2.0. Cologne, Germany: BAST 2010. http://www.druid-project.eu/Druid/EN/Dissemination/downloads_and_links/Final_Report.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=1 (accessed 9 Jan 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 46. International Council on Alcohol, Drugs and Traffic Safety (ICADTS): working group on prescribing and dispensing guidelines for medicinal drugs affecting driving performance. Utrecht, The Netherland: ICADTS; 2001. http://www.icadts.nl/medicinal.html (accessed 9 Jul 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 47. Legrand SA, Boets S, Meesmann U, et al. Medicines and driving: evaluation of training and software support for patient counselling by pharmacists. Int J Clin Pharm 2012;34:633–43. 10.1007/s11096-012-9658-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios. Utilización de medicamentos ansiolíticos e hipnóticos en España durante el periodo 2000 to 2012. Informe de Utilización de Medicamentos U/HAY/V1/. 2014;17012014 https://www.aemps.gob.es/medicamentosUsoHumano/observatorio/docs/ansioliticos_hipnoticos-2000-2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios. Utilización de medicamentos antidepresivos en España durante el periodo 2000 to 2013. Informe de Utilización de Medicamentos U/AD/V1/. 2015;14012015 https://www.aemps.gob.es/medicamentosUsoHumano/observatorio/docs/antidepresivos-2000-2013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 50. EUROSAT statistics explained. Medicine use statistics. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/File:Self-reported_use_of_prescribed_medicines_by_age_and_sex,_2014_(%25).png (accessed 20 Jul 2017).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.