Abstract

Purpose

Globally, prostate cancer treatment and outcomes for men vary according to where they live, their race and the care they receive. The TrueNTH Global Registry project was established as an international registry monitoring care provided to men with localised prostate cancer (CaP).

Participants

Sites with existing CaP databases in Movember fundraising countries were invited to participate in the international registry. In total, 25 Local Data Centres (LDCs) representing 113 participating sites across 13 countries have nominated to contribute to the project. It will collect a dataset based on the International Consortium for Health Outcome Measures (ICHOM) standardised dataset for localised CaP.

Findings to date

A governance strategy has been developed to oversee registry operation, including transmission of reversibly anonymised data. LDCs are represented on the Project Steering Committee, reporting to an Executive Committee. A Project Coordination Centre and Data Coordination Centre (DCC) have been established. A project was undertaken to compare existing datasets, understand capacity at project commencement (baseline) to collect the ICHOM dataset and assist in determining the final data dictionary. 21/25 LDCs provided data dictionaries for review. Some ICHOM data fields were well collected (diagnosis, treatment start dates) and others poorly collected (complications, comorbidities). 17/94 (18%) ICHOM data fields were relegated to non-mandatory fields due to poor capture by most existing registries. Participating sites will transmit data through a web interface biannually to the DCC.

Future plans

Recruitment to the TrueNTH Global Registry-PCOR project will commence in late 2017 with sites progressively contributing reversibly anonymised data following ethical review in local regions. Researchers will have capacity to source deidentified data after the establishment phase. Quality indicators are to be established through a modified Delphi approach in later 2017, and it is anticipated that reports on performance against quality indicators will be provided to LDCs.

Keywords: quality in health care, prostate disease, international health services

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To our knowledge, this is the largest clinical quality registry (CQR) to have been developed; it involves collecting data from, and reporting health outcomes to, contributing health services across 13 countries.

We outline the approach taken to establishing a CQR to monitor care provided to men with localised prostate cancer, including how the minimum dataset was determined, the governance structure and data security, hosting and access arrangements. It will assist researchers embarking on developing an international CQR.

We were unable to report the capability for 4/21 Local Data Centres to contribute the required data fields to the global registry because we did not translate data dictionaries to English.

Introduction

Globally, prostate cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer, behind lung cancer, and, in the developed world, it is the most common cancer among men.1 Survival has increased dramatically over the past 25 years. In developed countries, 92% of men are alive 5 years after diagnosis, with survival as high as 97% for men diagnosed before the age of 60.2 However, in low-income, middle-income countries survival rates are approximately half that of developed countries; 5-year survival in Indonesia is 44% and in both Thailand and India is 58%.3 Variation in incidence and outcomes also exists between racial groups, with the rate ratio of black:white men for prostate cancer incidence and mortality being 1.7 and 2.4, respectively.4 Variation in survival has principally been the result of lead time bias attributable to early diagnosis of asymptomatic disease. It has also, in some part, been due to variation in the quality of healthcare.5–7

This makes understanding variation in management of prostate cancer very important. Measuring variation in prostate cancer care and outcomes has traditionally been by assessment of compliance with evidence-based guidelines using quality indicators.8–10 Comparing performance of quality indicators across sites or benchmarking performance requires data fields to be consistently defined and collected at the same time points. The International Consortium for Health Outcome Measures (ICHOM) has developed standardised datasets for localised and advanced prostate cancer in an effort to improve the ability to compare health outcomes.11 12 These datasets provide a consistent approach to defining and recording data items and time points for their collection. The premise for development of standardised datasets by ICHOM was to encourage value-based healthcare13 and foster ‘positive deviance’ research,14 whereby all participating health services learn from those achieving excellent outcomes. In effect, the goal was to raise the bar for quality.

The TrueNTH Global Registry is an international registry to monitor prostate cancer care, applying the principles of collecting and using the ICHOM standardised clinical dataset. The TrueNTH Global Registry project aims to significantly improve the physical and mental health of men treated for prostate cancer by (i) examining the extent to which current practice in participating sites reflects evidence-based guidelines; (ii) systematically measuring clinical and patient-reported outcomes and key elements of care that have the potential to impact outcomes; (iii) comparing and sharing deidentified outcomes between participating sites; (iv) analysing variations to understand key drivers that deliver the best outcomes and (v) mobilising the exchange of knowledge among the prostate cancer clinicians, treating facilities and men diagnosed with prostate cancer.

The aim of this paper is to describe the methods used to develop the TrueNTH Global Registry project, an international registry for localised CaP. This paper is not a classical research paper but rather a cohort profile; it attempts to develop, in line with the respect of scientific approach, a working platform detailing how the registry will function. The approach outlined herein may assist other clinical specialties in developing an implementation model for an international clinical quality registry using a standardised clinical dataset, such as those developed by ICHOM.

Cohort description

Establishing the cohort and governance arrangements

In mid-2015, two parallel Expressions of Interest were extended to participate in the TrueNTH Global Registry project through authorised legal entities in countries where the Movember Foundation has a significant fundraising presence. The first was a call to nominate as the Global Project Coordination Centre and the second was to nominate as a participating site. Nominating sites were required to demonstrate some existing capacity to prospectively collect the ICHOM minimum dataset. Sites were advised that funding was available to assist in collecting data fields required by ICHOM but not currently being collected, and to support costs of transferring data to a central global coordination centre for analysis and development of benchmark reports. The Expression of Interest stipulated that initial funding would be provided for 3 years, after which an evaluation would be undertaken to assess future funding, based on the extent to which the TrueNTH Global Registry project achieved its intended projects aims.

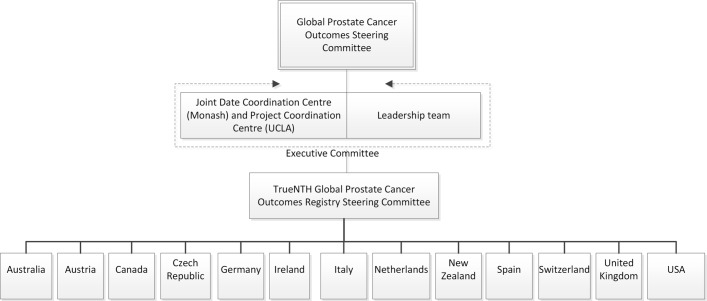

A Project Coordination Centre (PCC) and Data Coordination Centre (DCC) were appointed through a competitive peer-review process; the PCC based at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the DCC at Monash University in Australia. In total, 25 responses to the Expression of Interest were received from 12 countries. Together these respondents had capacity to collect data from 113 participating sites in 13 countries. Thirteen respondents nominated as single institutions, with the remaining respondents nominating to act on behalf of between 2 and 24 participating sites. Sites nominating to transmit data to the DCC were referred to as Local Data Centres (LDCs) figure 1 provides a summary of the LDCs and participating sites from each country nominating to be included in the TrueNTH Global Registry project.

Figure 1.

Details of the 12 countries nominating to participate in the TrueNTH Global Registry and distribution of the 113 participating sites across the 25 Local Data Centres in these 12 countries.

A governance framework was developed by Movember in collaboration with their Global Prostate Cancer Outcomes Steering Committee (figure 2). The PCC is responsible for the establishment and delivery of a project communication plan, stewardship of meetings of the Executive Committee and Project Steering Committee, monitoring of regulatory approvals in participating sites, guidance and development of methodological approaches to the data analyses, evaluation and interpretation of statistical output, provision of descriptive analysis of variations in outcomes across participating sites; development of hypotheses to explain variations in quality and outcomes among participating sites and coordination of activity to identify strategies and actions to test these hypotheses.

Figure 2.

Details of the governance hierarchy established for the TrueNTH Global Registry. At least one clinical lead from each country will contribute to the TrueNTH Global Registry Steering Committee.

The DCC will oversee data management and contribute to the projects’ execution with representation on the TrueNTH Global Registry Executive Committee. The role of the DCC includes developing the global register, its data dictionary and the TrueNTH Global Registryinitial protocol draft; building a technical solution for the secure transfer of data from sites to the DCC and training sites on its use; providing a research portal to enable participating sites to gain secure access to data (following relevant ethical approval); and leading a process to develop quality indicators to report back to participating sites.

The LDC may represent numerous hospitals or institutions or may be individual sites collecting data directly from patients. LDCs will be responsible for transmitting data to, and distributing reports from, the DCC. A clinical lead will be appointed for each LDC as the primary contact for the project.

A TrueNTH Global RegistryExecutive Committee was formed with clinician, epidemiologist and scientist representatives, and members of the DCC, the PCC and the Movember Foundation. Its responsibilities include reviewing and endorsing the project work plan, protocol, quality indicator set, standard operating procedures and terms of reference for committees and working groups; monitoring progress of participating sites and LDCs; and identifying opportunities for improvement in quality of care and reviewing suggestions made by the Project Steering Committee.

The Project Steering Committee includes representatives from each contributing country (nominated from the clinical leads of the LDCs), the PCC, DCC, Movember Foundation, the Executive Committee and at least one consumer and quality-of-care expert. It will initially select the quality indicators and how they will be presented and will review prostate cancer management processes and structures across contributing sites to identify those factors associated with high-quality care. A Communication and Action Plan will be created with the Committee to maximise the exchange of knowledge and facilitate opportunities for policy transformation and funding for prostate cancer innovation projects.

Findings to date

A Data Discovery study was initiated in late 2015 with sites responding to the Expression of Interest to assess existing capacity to collect the ICHOM standardised dataset and finalise the dataset to be collected by the TrueNTH Global Registry project. Nominating sites were asked to provide the DCC with their data dictionaries to assess the extent to which they were comparable, complied with the ICHOM minimum dataset and could realistically comply by 2017. A project coordinator from the DCC collated the data dictionaries and, in addition to assessing compliance with the ICHOM Localised Prostate Cancer Standardised dataset, identified data fields collected across participating sites but not in the ICHOM dataset. A final approved dataset and budget were deliverables from this work programme.

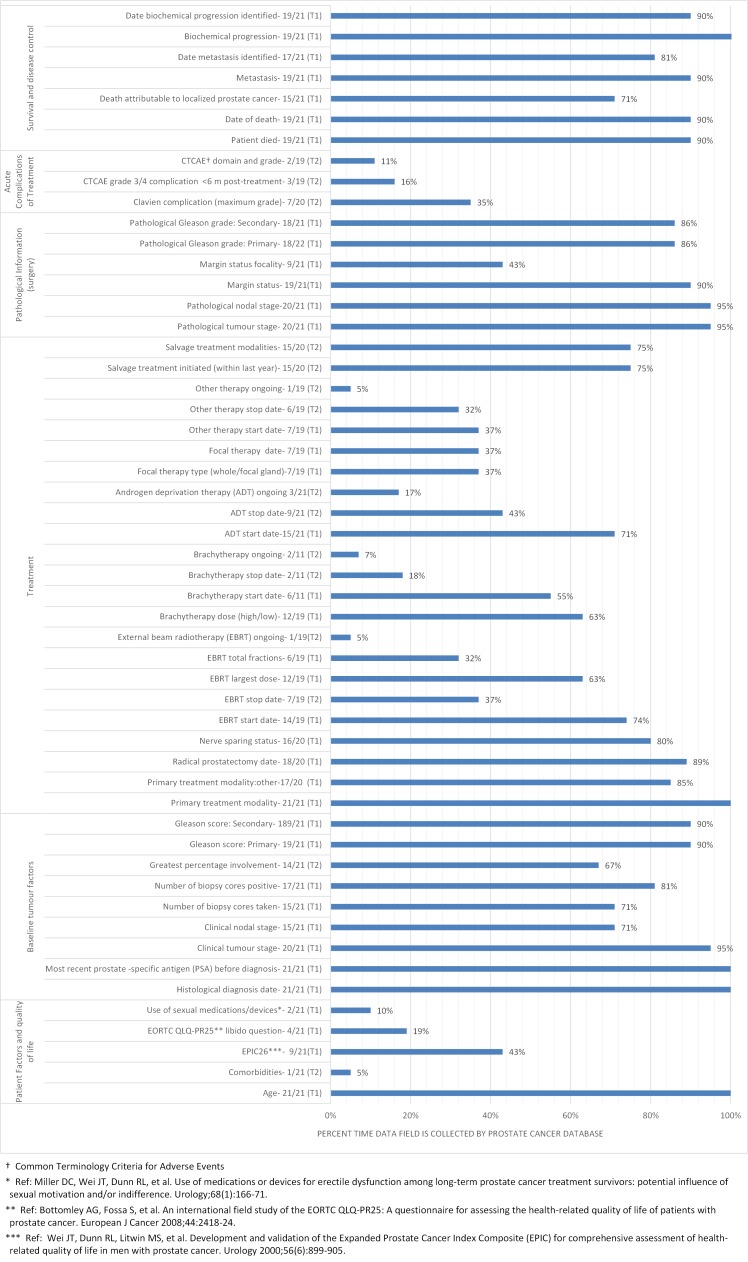

Data dictionaries were reviewed from 21/25 LDCs. Excluded data dictionaries were those from Italy (n=2), the Netherlands (n=1) and Spain (n=1) as these were not in English. For the four data dictionaries which were not documented in English, verbal contact was made with the principal investigator in each LDC, each of whom spoke English, to understand where gaps existed in their site’s ability to collect the ICHOM dataset. Results from the four LDCs where the data dictionary was not provided for analysis were not included in this analysis because verbal correspondence could not be validated. Figure 3 provides a summary of the results of the data dictionary exercise.

Figure 3.

Distribution of data items collected by the 21 Local Data Centres across the categories of (1) patient factors and quality-of-life, (2) baseline tumour factors, (3) treatment, (4) pathology information, (5) acute complications of treatment and (6) survival and disease control.

The Extended Prostate Cancer Index-26 questions15 were collected by 43% of sites; 58% reported they could commence collection using this instrument in 2017. Time points at which patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) data collection most often occurred were at baseline and at 12 months post treatment. Only one site complied with the follow-up schedule outlined by ICHOM.

There were a number of data fields collected by nominating sites which were not included in the ICHOM dataset. These included radiological diagnostic tests, prostate specific antigen (PSA) levels prior to treatment and annually; type of surgical approach undertaken for radical prostatectomy and biopsy details prior to active treatment (if this is not the same as the diagnostic biopsy).

A stakeholder meeting with principal investigators and senior information technology (IT) personnel from nominating sites was held in late 2015 prior to the development of the project protocol. Its purpose was to share findings from the Data Discovery study, describe the proposed framework for data transfer and hosting, understand potential barriers to data transfer, discuss potential ethical issues which might impact the project and identify broad barriers and enablers to project implementation.

The Executive Committee reviewed the results of the Data Discovery study. As a result of the heterogeneity of data collected across sites and difficulty reported by the principal investigators at the stakeholder meeting in being able to immediately incorporate the full ICHOM dataset, a two-tiered system for data was introduced. In general, data items were denoted as mandatory if they were likely to be required for risk adjustment or for generation of quality indicators. Start dates for each treatment were mandatory as they determined the time points for follow-up survey of patients. In addition, because a requirement of participating in the project was that sites collected patient-reported outcomes (and this received funding support by Movember), these fields were also mandatory. Tier 1 items (T1) were considered mandatory and Tier 2 items (T2) were encouraged but were non-mandatory. This enabled sites to contribute with minimal upfront investment while allowing for sites collecting a more advanced dataset to contribute more extensive data. Figure 3 outlines those data fields included as T1 and T2 fields. Table 1 summarises changes introduced by the Executive Committee following the Data Discovery review study. A survey will be distributed to LDCs and participating sites on an annual basis to understand structural factors which might impact on outcomes.

Table 1.

Summary of amendments to the existing International Consortium for Health Outcome Measures (ICHOM) dataset and new fields introduced into the TrueNTH Global Registry project

| Amendments to the existing ICHOM data fields | Patient-reported quality of life to only be collected as a mandatory (Tier 1) field at baseline and 12 months post diagnosis/treatment. Other time points will be non-mandatory (Tier 2) |

| Comorbidities will only be Tier 2 at baseline | |

| Stop date for focal therapy will be removed as this is a day procedure | |

| Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) will be split into chemical and surgical groups | |

| New mandatory (Tier 1) fields introduced | Clinical metastases stage |

| Surgical approach (open, robot-assisted, laparoscopic, conversion) | |

| ADT chemical agents | |

| Date of orchidectomy | |

| Whole gland ablation and date of initiation | |

| New non-mandatory (Tier 2) fields introduced | Method of diagnosis |

| Use of radiological tests (MRI, bone scans, CT and PET scans) to target biopsies and/or assist in staging at baseline and prior to primary treatment initiation (if different to baseline). | |

| MRI, bone scans, CT and PET scan dates | |

| Details of the most recent biopsy prior to primary treatment initiation | |

| Details of the clinical stage (tumour, node, metastases) prior to primary treatment initiation | |

| PSA levels prior to initiation of treatment | |

| New definitions introduced | Diagnostic PSA defined as occurring within 180 days prior to prostate cancer biopsy or transurethral resection of the prostate procedure |

PSA, Prostate specific antigen.

Data management

A proposed data management strategy was presented to the stakeholder meeting and has been subsequently modified to facilitate data transfer from LDCs to the DCC and research activity within a secure environment. A data dictionary has been developed, with minor amendment to the ICHOM data dictionary. LDCs will be responsible for formatting data according to the data dictionary prior to transfer. Data will be transmitted through an Extract, Transfer, Load system in a normalised format. Records which do not comply with the required format or which violate the validation rules will be returned to sites for action. Data extracts will be transmitted to the DCC each 6 months. It is probable that duplicate records will be transmitted, and that existing records may be updated if they comply with the field validation rules. A warning report will be provided to inform sites when data have been overwritten.

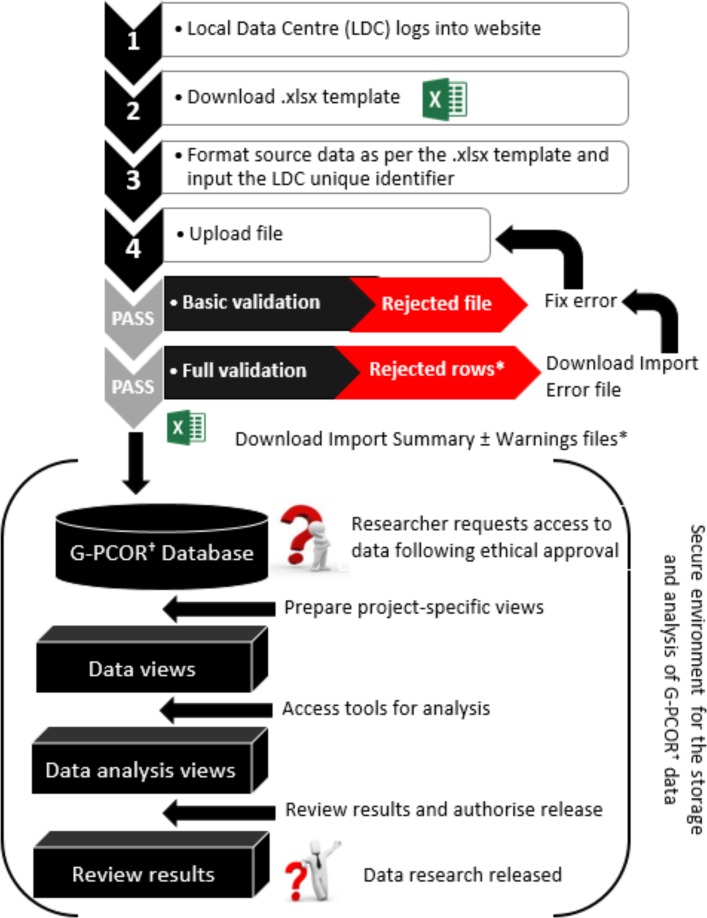

Data will be hosted in a secure environment with access restricted via a secure data access solution. Authorisation points will prevent data from being accessed without appropriate predetermined approvals. Once authorised, users will have time-limited access to a Microsoft Windows-based remote desktop environment with controls on copy/paste, print and file transfer, and no external network access. The data itself are protected and cannot be extracted, placing tight controls over data exposure. Once research has been completed, it may be released through a subsequent authorisation process. Data import and handling procedures are summarised in figure 4. When discussed at the stakeholder meeting in December 2015, the group considered that this approach would provide adequate safeguard of data and satisfy requirement of human research ethics committees and information security review teams.

Figure 4.

Description of the process by which (1) data from the Local Data Centres are transmitted to the TrueNTH Global Registry; and (2) researchers will request and receive research data for statistical analysis. It will not be possible to removed data from the secure storage environment without authorisation designated by the Executive Committee. *Records of patients with invalid data will be rejected, with details shown in an Import Errors file. Valid patient records will be imported into the TrueNTH Global Registry

Future proposed activity

Quality indicators will be developed using a modified Delphi approach. This approach involves first identifying from the literature potential quality indicators and then, though a series of rounds with selected experts, determining which ones rate highest for inclusion in the registry.16 Panel members will include a representative selection of men and their partners, specialty groups involved in the management of men with localised prostate cancer and researchers/epidemiologists with experience in data and prostate cancer disease. Project Steering Committee members will be invited to participate in this project.

Software has been developed to electronically capture PROMs (ePROMs). Patients may complete the ePROMs in the hospital or they may be forwarded via electronic mail for them to complete at home. An audit project will be undertaken to assess the quality of the data contributing to the TrueNTH Global Registry project. This activity will be led by LDCs and will be multifaceted. External validation with data sources such as administrative coding systems and cancer registries will assess the proportion of the eligible population that the local registry includes. Data dictionaries have been developed to provide clear rules on how data are defined and coded and have been distributed to all LDCs with the TrueNTH Global Registry protocol. Reliability of data will be assessed by LDCs through recapture of patient data on a small percentage of cases. Automated range and consistency validation checks will be undertaken as data are imported into TrueNTH Global Registry to ensure that data outside permitted values are identified, rejected and returned to LDCs for review. Principal outcomes monitored by the registry are independently assessed by the patient and pathology/radiology reports, thereby minimising risk of outcome bias.

The PCC and DCC will collaborate to assess how to present indicators to participating sites and LDCs and to finalise the structural indicators to be collected periodically.

Strengths and limitations

The TrueNTH Global Registryproject offers the potential to improve care provided to men with prostate cancer by using a consistent dataset to identify and reduce variation in patient outcomes. It is hypothesised that this will be achieved by assessing attributes of high-performing organisations and working with an engaged clinical team across countries to make local changes. The impact of these changes will be assessed by the registry in a consistent and standardised approach through compliance with quality indicators. The project is ambitious and, if successful, may provide a transformational approach to quality and safety activity at a global scale.

The concept of a global registry is not unique. International registries have been established to monitor diseases and interventions associated with significant health burden such as orthopaedic surgery17 and transplantation18; others have been set up to monitor rare diseases, for which single-institution/single-country registries would take many years to accumulate enough meaningful data to advance disease treatment.19 Common priorities in the establishment phase of international registries include harmonising data through consistent data definitions. Other registries have used a similar approach to ICHOM in providing a framework so that common data elements can be shared between registries.20

The approach taken by the TurueNTH Global Registry to data analysis is to collect reversibly anonymised patient-level data in a central data repository which has strict security standards and controls over data access. A centralised approach provides an effective means of developing benchmark reports and undertaking consistent data validation checks on data, and a rich resource for initiating quality improvement research activities. Other registries have adopted a distributed approach to data analysis to avoid security issues, where each registry retains its own data and conducts analysis in a consistent manner.17 21 Sites presenting the protocol to ethics committees for review have not found this to be a barrier provided appropriate security certificates are provided, but this will need to be monitored as more sites sign up to the registry.

There are a number of challenges which the TrueNTH Global Registryhas considered beyond its establishment phase. Experience from another international registry suggests that difficulty sustaining funding, inadequate local IT knowledge to provide uploads and changing data legislation across countries have potential to pose difficulties.22 Maintaining sustained motivation and support of stakeholders is a challenge for all research activity. Movember has provided funds to assist sites in setting up automated data transfer solutions and more sustained funding to fund gaps in existing data collection. The DCC has developed user-friendly software to facilitate data uploads in file formats that are easily originated from existing registries. Legislative barriers have been minimised by the transmission of reversibly anonymised data. Collection of PROMs is a core element of the registry yet, to date, has been poorly collected by participating sites and LDCs. It will provide a challenge to efficiently collect this information from patients, particularly at baseline due to the lag in coding and transmission of prostate cancer notification data by hospitals. However, high completion rates of 86% have been recorded by hospitals using ePROMs, attributed largely to them having an engaged and supported roll-out team.23 We will encourage sites to adopt such an approach and will monitor the impact of different strategies on PROMs completion rates in the immediate and longer terms. While funding has only been provided to collect PROMs at baseline and 12 months post-diagnosis/primary treatment, hospitals are encouraged to contribute additional PROMs if they are being collected and the software will not restrict the number of PROMs for each patient uploaded by hospitals. To maintain the motivation of sites, the PCC will distribute regular updates and the DCC will distribute six monthly quality indicator benchmark reports highlighting where participating sites sit relative to others. The Project Steering Committee will have regular web conferences to review data and discuss potential interventions to reduce variation. Recognition and academic credit will likely also encourage project participation and, to this end, authorship guidelines have been developed and agreed on and are documented in the study protocol. An advantage of this project is that sites already have established registries so additional burden to contribute to the international registry is minimal.

While other international registries have been developed, the novelty of this global clinical quality registry is its core purpose to provide useful, clinically relevant information back to contributing sites to enable global benchmarking and feedback which will empower local action. In doing so, we hope to realise the goal of reducing unwarranted variation and promoting excellence.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Mr Tom Solopotias, Business Analyst, Monash University, for assistance in collating data dictionaries from participating organisations.

Footnotes

Contributors: SE, JM, CM, PV and ML contributed to the concept and design of the study. SE, FS, SC, JM, CM, JL, HH, MS contributed to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data. SE wrote the first draft of the protocol. JM, CM, JL, HH, FS, SC, PV and ML revised the protocol critically for important intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript to be published.

Funding: This work was supported by the Movember Foundation.

Competing interests: SE receives a Monash Partners Academic Health Science Centre Clinician Fellowship.

Ethics approval: Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (project 8437).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: This study describes attributes of databases and contains no patient-level data.

References

- 1. International Agency for Research on Cancer. World Cancer Report 2014. Lyon, France: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer Survival and Prevalence in Australia from 1982 to 2010. Canberra: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3. American Cancer Society. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Global Cancer Facts & Figures. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society Inc, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A, et al. . Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:7–30. 10.3322/caac.21332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Burnett AL. Racial disparities in sexual dysfunction outcomes after prostate cancer treatment: myth or reality? J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 2016;3:154–9. 10.1007/s40615-015-0126-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jayadevappa R, Chhatre S, Johnson JC, et al. . Variation in quality of care among older men with localized prostate cancer. Cancer 2011;117:2520–9. 10.1002/cncr.25812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schroeck FR, Kaufman SR, Jacobs BL, et al. . Regional variation in quality of prostate cancer care. J Urol 2014;191:957–63. 10.1016/j.juro.2013.10.066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sampurno F, Earnest A, Kumari PB, et al. . Quality of care achievements of the prostate cancer outcomes registry-victoria. Med J Aust 2016;204:319 10.5694/mja15.01041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Spencer BA, Miller DC, Litwin MS, et al. . Variations in quality of care for men with early-stage prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3735–42. 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.2555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Herrel LA, Kaufman SR, Yan P, et al. . Health care integration and quality among men with prostate cancer. J Urol 2017;197:55–60. 10.1016/j.juro.2016.07.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Martin NE, Massey L, Stowell C, et al. . Defining a standard set of patient-centered outcomes for men with localized prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2015;67:460–7. 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.08.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Morgans AK, van Bommel AC, Stowell C, et al. . Development of a standardized set of patient-centered outcomes for advanced prostate cancer: an international effort for a unified approach. Eur Urol 2015;68:891–8. 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Porter ME. A strategy for health care reform-toward a value-based system. N Engl J Med 2009;361:109–12. 10.1056/NEJMp0904131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bradley EH, Curry LA, Ramanadhan S, et al. . Research in action: using positive deviance to improve quality of health care. Implement Sci 2009;4:25 10.1186/1748-5908-4-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, et al. . Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology 2000;56:899–905. 10.1016/S0090-4295(00)00858-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dalkey NC. The Delphi Method: an Experimental Application of Group Opinion. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sedrakyan A, Paxton EW, Phillips C, et al. . The International Consortium of Orthopaedic Registries: overview and summary. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011;93(Suppl 3):1–12. 10.2106/JBJS.K.01125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gómez MP, Pérez B, Manyalich M. International Registry in Organ Donation and Transplantation--2013. Transplant Proc 2014;46:1044–8. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.11.138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Forrest CB, Bartek RJ, Rubinstein Y, et al. . The case for a global rare-diseases registry. Lancet 2011;377:1057–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60680-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bellgard MI, Macgregor A, Janon F, et al. . A modular approach to disease registry design: successful adoption of an internet-based rare disease registry. Hum Mutat 2012;33:E2356–E2366. 10.1002/humu.22154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sedrakyan A, Marinac-Dabic D, Holmes DR. The international registry infrastructure for cardiovascular device evaluation and surveillance. JAMA 2013;310:257–9. 10.1001/jama.2013.7133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Viviani L, Zolin A, Mehta A, et al. . The European Cystic Fibrosis Society Patient Registry: valuable lessons learned on how to sustain a disease registry. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2014;9:81 10.1186/1750-1172-9-81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Malhotra K, Buraimoh O, Thornton J, et al. . Electronic capture of patient-reported and clinician-reported outcome measures in an elective orthopaedic setting: a retrospective cohort analysis. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011975 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]