Delays in receiving medical care can adversely affect health. The Institute of Medicine defines access to health services as “the timely use of personal health services to achieve the best health outcomes.”1 Barriers to timely care, whether in the United States or in the West Bank, are very often attributable to political processes.

In the article by McNeely et al. (p. 77), the authors argue that there are both immediate and long-term negative health consequences with “Israeli-imposed movement restrictions in the occupied Palestinian territory.” They appropriately use the word “association” rather than “causation” as the methodology employed cannot prove any direct cause–effect for many reasons, not the least of which are the well-documented vagaries of human memory over such a long period. Furthermore, data on baseline characteristics are not provided, including health status of the included patients, making inference on temporality (cause precedes effect) impossible. As well, there is the potential problem of confounding, briefly addressed by McNeely et al. (e.g., the longer one suffers from a “serious medical condition,” the more likely the need to travel for health care; the more longstanding a “serious medical condition,” the more likely one will encounter a travel restriction [longer exposure]).

The major association reported was worse self-rated health (odds ratio [OR] = 4.3; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.43, 12.91) and greater limits to daily functioning (OR = 6.49; 95% CI = 2.06, 20.45) among those with a serious medical condition who were barred from traveling for medical care or did not try to cross barriers, compared with a referent group with no reported restrictions. One criterion for causation is consistency, yet the authors do not explain the curious anomaly that respondents who reported “being barred and delayed” did not show worsened self-rated health (OR = 0.73; 95% CI = 0.25, 2.10) compared with the referent group. Finally, the small proportion of the variance in these two health outcomes explained by all variables (including delays and restrictions, gender, etc.) in the multivariable models (pseudo R2 of only 6.6% and 13.3%, respectively) suggests that these delays are but minor factors in determining health status.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Methodology aside, the historical context matters. As McNeely et al. rightly point out, echoing Virchow, “The fundamental cause of disease is political” (emphasis ours). True, but to address “political” problems, one cannot avoid wrestling with the past. Analogously, when one is diagnosing a patient’s illness, a history, involving a careful, dispassionate chronological analysis of symptoms and exposures, must be undertaken. Although an exhaustive historical review of the region’s political conflicts is beyond our scope, a useful start would be the comprehensive history by Dennis Ross, chief Middle East peace negotiator under both Republican (Bush Sr.) and Democrat (Clinton) administrations.2

Israeli authorities could undoubtedly handle many transfers through checkpoints more efficiently and sensitively, and possibly raise fewer barriers. But McNeely et al. have not addressed the legitimate reasons for which Palestinians might be stopped. The word “security,” is not mentioned anywhere in their article. A reader, naïve to historical circumstances, might come to the wholly erroneous conclusion that checkpoints are arbitrarily constructed, or worse, malevolently placed to harm the health of Palestinians, when actually they are a response to violence.

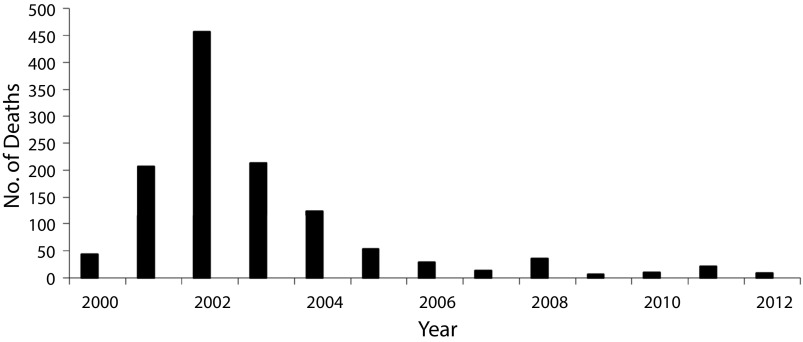

Behind the “political conflict” alluded to by McNeely et al. there is the strong correlation between delays at checkpoints and the preceding deaths of Israelis (both Arab and Jew) in terrorist attacks. For instance, as reported in the US State Department report for 2002 (bit.ly/2xwHvwT), in 2001 alone, “nearly 2,000 terror attacks, including suicide bombings, drive-by shootings, mortar and grenade attacks, and stabbings took place during the year in the West Bank, Gaza, and Israel proper. Also . . . more than 200 Israelis were killed and over 1,500 injured, a sharp increase over the previous year.” In fact, a graph of terrorist-caused deaths (Figure 1) correlates well with the rate of delays as shown in McNeely et al.’s Figure 1b.

FIGURE 1—

Israeli Deaths Attributable to Palestinian Violence: 2000–2012

Source. Jewish Virtual Library. Available at: http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/number-of-terrorism-fatalities-in-israel. Accessed November 16, 2017.

At checkpoints, although the number of innocent travelers is huge and the number of potential perpetrators miniscule, the security philosophy is that all it takes is for one terrorist to get through and kill. A particularly chilling yet instructive example, broadly reported by the international press, is that of Wafa Samir Ibrahim al-Biss. At one point during the study period, in 2005, this 21-year-old woman from Gaza was provided with a multientry permit to receive care in Israel for multiple burns caused by a home gas explosion. She was stopped at a Gaza border checkpoint with 10 kilograms of explosives hidden in her underwear. Although al-Biss had been cared for on many occasions by staff at Soroka Hospital (where one of us [A. M. C.] works), under interrogation she offered “[T]oday, I wanted to blow myself up in the hospital. Maybe even in the one I was treated. . . . I wanted to kill 20, 50 Jews.”3

Earlier in the study period, another particularly egregious checkpoint event occurred in a Red Crescent Ambulance where explosive material was hidden under a gurney that carried a sick child.4 Following this occurrence, the International Red Cross publically reiterated Israel’s right to examine such vehicles as long as this check did not unduly delay the patient’s passage.

PALESTINIANS WHO ACCESS CARE

Undoubtedly, the short- and long-term suffering of an ill Palestinian delayed at a checkpoint is always unfortunate, and occasionally even tragic. However, despite ongoing terror threats, and even during unrest and wars, many Palestinians do pass daily into Israel for medical care. Israeli hospitals have long provided Palestinians with extensive medical services. For example, during the research period (in 2005 alone), approximately 123 000 Palestinians were treated at just one institution, Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem, which included 15 000 admissions as well as 32 000 visits to the emergency department.5

In general, special entry permits are issued in humanitarian cases for ill people, their chaperones, and for Palestinian medical teams. For example, more recently, in 2016, 93 890 such authorizations were issued for patients (plus 100 722 for accompanying family) to be treated at hospitals throughout Israel. At the two West Jerusalem Hadassah hospitals alone, 15 743 patients, comprising more than one third of the total, came through checkpoints and were cared for there. Another 16% (6577 patients) crossed into Israel and were treated in hospitals in East Jerusalem.5

During the same year, 9832 Palestinian children with birth defects and chronic diseases were treated in Israeli hospitals. During the first half of 2017, 46 132 such permits have been issued and a further 2163 authorized Palestinian medical personnel to work or be trained in Israel or East Jerusalem (written personal communication, October 4, 2017, Ido D. Dechtman and Yuval Ran, Medical Corps, Tel Aviv, Israel Defense Forces). Another noteworthy example of Israeli compassion for the suffering of her Arab neighbors is the treatment of more than 4000 victims of the Syrian Civil War in civilian hospitals at Israeli government expense.6

POLITICAL SOLUTION

We quite agree that in the end the solution is not medical, but must be political. Certainly the health of both Palestinians and Israelis will improve when the threat of violence ends and hence the need for checkpoints disappears. This peaceful future must surely be the fervent hope of us all.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Yuval Ran, MD, and Elon Glassberg, MD, for their helpful comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Millman M, editor. Institute of Medicine; Committee on Monitoring Access to Personal Health Care Services. Access to Health Care in America. 4. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross D. The Missing Peace? The Inside Story of the Fight for Middle East Peace. New York, NY: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deviri M. My dream was to be a suicide bomber, I want to kill 20, 50 Jews. Yes, even babies. The Telegraph. June 26, 2005. Available at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/israel/1492836/My-dream-was-to-be-a-suicide-bomber.-I-wanted-to-kill-20-50-Jews.-Yes-even-babies.html. Accessed October 5, 2017.

- 4.Harel A, Hass A, Algazy Y. Bomb found in Red Crescent ambulance. Haaretz. March 29, 2002. Available at: https://www.haaretz.com/bomb-found-in-red-crescent-ambulance-1.49189. Accessed October 5, 2017.

- 5.Richter ED, Stein Y, Pileggi T. Just war theory, choice and necessity and Israel’s response to genocidal threats: an evidence-based approach. In: Neusner J, Chilton BD, Tully RE, editors. Just War in Religion and Politics. New York, NY: University Press of America; 2013. pp. 29–354. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bahouth H, Shlaifer A, Yitzhak A, Glassberg E. Helping hands across a war-torn border: the Israeli medical effort treating casualties of the Syrian Civil War. Lancet. 2017;389(10088):2579–2583. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30759-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]