The devastation caused by Hurricane Maria exposed the colonial condition of Puerto Rico. If anything has been evidenced in the aftermath of the hurricane, besides the sociopolitical crisis in Puerto Rico, it is the ability of the people of Puerto Rico to overcome adversity. In this process we witnessed solidarity and commitment to the restoration of our communities. I could share many examples, but would like to highlight two, that, to my understanding, best represent this.

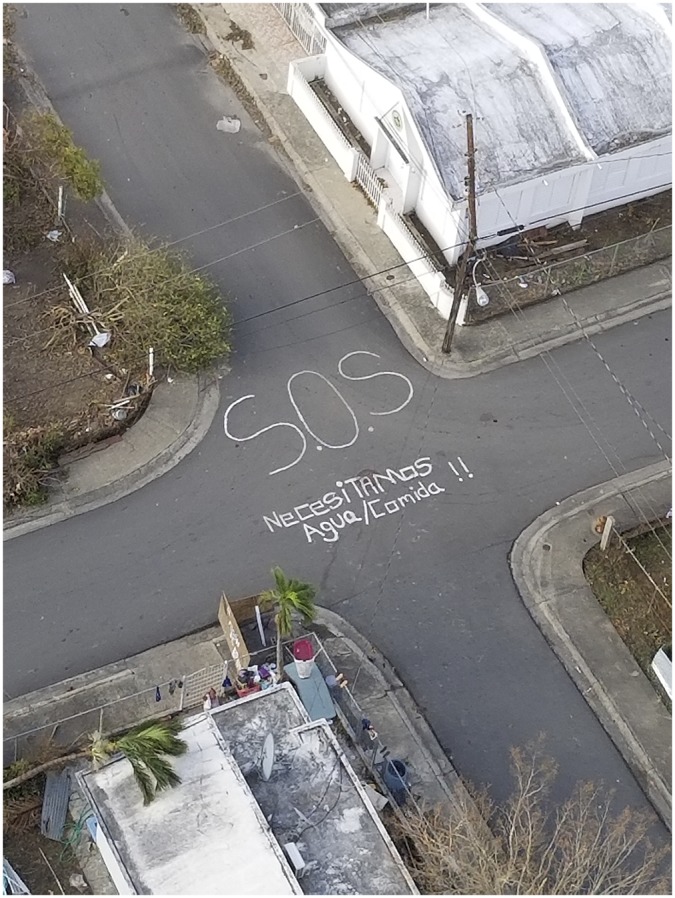

The text says “SOS, We need water/food.”

Source. Photo taken by Angelina Ruiz-Lambides in Punta Santiago, Cayo Santiago Biological Field Station, University of Puerto Rico-School of Medicine. Printed with permission.

First, the Puerto Rican diaspora played a major role in the preparation for and response to the natural disaster. During and after the impact of Hurricane Maria, we witnessed Puerto Ricans not currently living in the islands supporting and organizing aid for those in Puerto Rico. Social media became a place to share their hopes, frustrations, and readiness to assist. In Puerto Rico, there are nearly 3.5 million residents, but there are many more Puerto Ricans not living on the islands. Yet, distance has not curtailed their commitment to Puerto Rico. I and many others are thankful to the Puerto Rican diaspora for the pressure they exerted upon politicians and in the national and international media. Their interventions made the humanitarian crisis experienced in Puerto Rico visible, helped in the emergency response, and sustained public discussion.

Secondly, community-level actions were fundamental in restoring access to neighborhoods and, ultimately, saving lives. One major failure after the impact of Hurricane Maria was the time it took national and federal authorities to reach rural areas of Puerto Rico. When media were able to reach these areas, most of the images and stories shared showed communities rallying to assist elders in getting drinking water, clearing debris from roads, and organizing shared cooking spaces.

The experience of Puerto Rico is shared with that of other countries in the Caribbean region known to be in the “Hurricane Alley.” Although certain disasters and public health emergencies can be predicted in this region, it is not only their geographical location, but also their colonial or postcolonial status, with chronic financial and public health implications, that increases their vulnerability to such disasters.

AN UNINCORPORATED TERRITORY

Puerto Rico is an organized but unincorporated territory of the United States of America since 1898, after the Spanish–American War. Nearly half of the adults in the United States do not know that Puerto Ricans are fellow citizens,1 yet Puerto Ricans are US citizens by birth since 1917. As an unincorporated territory of the United States, Puerto Rico lacks self-determination, and Puerto Ricans on the islands do not have full representation in Congress and cannot vote for president. Furthermore, because of Puerto Rico’s territorial status, US federal mandates take precedence over local legislation and policies in all areas of governance.

As a territory, Puerto Rico also contributes to the annual appropriation of funding to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and relies on its support in case of emergencies. However, the destruction brought by Hurricane Maria exposed colonial laws that limit the scope of actions that Puerto Rico has in response to emergencies. Examples of these laws are The Merchant Marine Act of 1920, also known as the Jones Act, and the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act or PROMESA. The Jones Act established that the maritime waters and ports of Puerto Rico are controlled by US agencies.2 Under this kind of control, the cost of consumer goods arriving to Puerto Rico can be higher than in the continental United States. The Jones Act also restrains the ability of non-US vessels and crews to engage in commercial trade with Puerto Rico. Similarly, in 2016, PROMESA was imposed on Puerto Rico and its inhabitants as a way to deal with the economic crisis.3 PROMESA limits the Puerto Rican government’s disaster response by restricting the amount of resources the state can mobilize locally in attending to the crises brought by the 2017 hurricane season.

“FINANCIAL CRISIS”

The so-called “financial crisis” that Puerto Rico is facing dates back to 1917. The same law that made Puerto Ricans US citizens empowered the islands to raise money by issuing tax-exempt bonds. That centenary provision helped successive Puerto Rican governments accrue an unmanageable debt as some investors have grown tax-averse and eager to shelter income. Over time, the sociopolitical context of Puerto Rico changed; significant transformations in federal laws took place; a substantial amount of professionals, students, and families left the islands; and Congress stripped Puerto Rico of bankruptcy rights.

Currently, Puerto Rico owes more than $100 billion in bonds and unpaid pension debts. This represents nearly 70% of the territory’s gross domestic product. This debt has not been audited, but under the provisions of the PROMESA law, a Fiscal Oversight and Management Board has been instituted, and under its austerity budget, the Puerto Rican government has already established several measures, including increases in taxes and cuts in public services, to ensure debt obligations see payment.

What Puerto Rico has experienced since September 2017 was a perfect storm caused by the natural disaster of a major hurricane and a human-made financial crisis manufactured by bankers and predatory class of investors. Hurricane Maria was the first major hurricane of the 21st century to land on Puerto Rican soil. The country had experienced similar atmospheric events in 1928, 1989, and 1998, but Puerto Rico never had to overcome the impact of a major hurricane under the current political and economic constraints. Advances in meteorological sciences facilitate reliable information that is critical for individual and social preparedness in the event of hurricanes. Under the economic and social circumstances imposed by austerity measures in Puerto Rico, it was impossible for individuals and their government to be prepared for hurricanes and their aftermath.

PUBLIC HEALTH PROBLEMS

Puerto Rico is also burdened with major public health problems. When compared with US states and territories, Puerto Rico has the highest prevalence rates of premature births,4 one of the highest incidence rates of HIV,5 and was the focal point of the Zika virus epidemic.6 The potential implications of the aftermath of Hurricane Maria are severe for public health, when one considers that Puerto Rico is also structurally underresourced. A lack of systematic health and humanitarian disaster relief has led, predictably, to outbreaks of infectious disease (e.g., leptospirosis, scabies), limited access to clean water, and malnutrition, among other problems. The possible implementation of further austerity measures on Puerto Rico’s government budget raises even more concerns about the availability of local resources to address the health care challenges posed by the public health situation after Hurricane Maria. Moreover, the federal response to the emergency in Puerto Rico has been slow and limited. Poverty has the largest impact in terms of health inequities after the hurricane and magnify the impact of social determinants of Puerto Ricans’ health (e.g., housing, health care services, access to clear water and sanitation).

RESILIENCE? I CALL IT RESISTANCE

The community response in Puerto Rico evidenced fundamental collective competencies that public health workers must nourish. We must continue supporting the development and implementation of evidence-based interventions that use relevant theories. Any such interventions should be aimed not only at the individual, but also, importantly, at the community and structural levels to improve and sustain healthy environments. We have the capacity to develop and respond with grass-root initiatives that might be more culturally relevant than poorly adapted evidence-based interventions developed elsewhere.

Some may call what happened in Puerto Rico after the impact of Hurricane Maria resilience; I call it resistance. We have not been knocked down. In any case, the impact of Hurricane Maria may be providing the evidence needed to recognize colonialism as the ultimate social determinant of health in Puerto Rico.

DISASTER IN CONTEXT

Puerto Rico is an archipelago located in the Caribbean basin, 1000 miles southeast of Florida. On September 20, 2017, Hurricane Maria struck Puerto Rico as a category 4 hurricane. This was just 2 weeks after category 5 Hurricane Irma impacted Puerto Rico and caused significant damage to the electric infrastructure, houses, and roads leading to the declaration of disaster zones in nearly 30 municipalities. In early October 2017, it was estimated that the impact of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico included nearly 51 confirmed deaths and more than 900 more caused by—alledgedly—natural causes, the total destruction of the electric infrastructure, major interruptions in telecommunications, significant damage to highways and roads, and limited access to potable water and food. In the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, issues of governance were evident, as well as limited ability in the implementation of emergency preparedness plans and, perhaps most importantly, the impact of structural determinants of health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author is thankful to Enbal Shacham, PhD, Adriana Garriga-López, PhD, Alfredo Morabia, MD, PhD, and members of the SexTEAM at the University of Puerto Rico–Medical Sciences Campus for helpful comments on earlier versions of this editorial.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1. Morning Consult. National tracking poll #170916. Available at: https://morningconsult.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/170916_crosstabs_pr_v1_KD.pdf. Accessed October 14, 2017.

- 2. Merchant Marine Act, Pub L No. 66-261, 41 Stat 988 (1920).

- 3.Congress of the United States of America – House of Representatives. Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA). Available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/5278/text. Accessed October 14, 2017.

- 4. March of Dimes. 2106 preterm birth report card. Available at: https://www.marchofdimes.org/materials/premature-birth-report-card-united-states.pdf. Accessed October 14, 2017.

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2015; vol. 27. 2016. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Accessed October 14, 2017.

- 6. Rodríguez-Díaz CE, Garriga-López A, Malavé-Rivera SM, Vargas-Molina RL. Zika virus epidemic in Puerto Rico: health justice too long delayed. Int J Infect Dis. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]