Abstract

Objective:

To assess cross-sectionally whether lower cardiac index relates to lower resting cerebral blood flow (CBF) and cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR) among older adults.

Methods:

Vanderbilt Memory & Aging Project participants free of stroke, dementia, and heart failure were studied (n = 314, age 73 ± 7 years, 59% male, 39% with mild cognitive impairment). Cardiac index (liters per minute per meter squared) was quantified from echocardiography. Resting CBF (milliliters per 100 grams per minute) and hypercapnia-induced CVR were quantified from pseudo-continuous arterial spin-labeling MRI. Linear regressions with ordinary least-square estimates related cardiac index to regional CBF, with adjustment for age, education, race/ethnicity, Framingham Stroke Risk Profile score (systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, diabetes mellitus, current cigarette smoking, left ventricular hypertrophy, prevalent cardiovascular disease [CVD], atrial fibrillation), APOE ε4 status, cognitive diagnosis, and regional tissue volume.

Results:

Lower cardiac index corresponded to lower resting CBF in the left (β = 2.4, p = 0.001) and right (β = 2.5, p = 0.001) temporal lobes. Results were similar when participants with prevalent CVD and atrial fibrillation were excluded (left temporal lobe β = 2.3, p = 0.003; right temporal lobe β = 2.5, p = 0.003). Cardiac index was unrelated to CBF in other regions assessed (p > 0.25) and CVR in all regions (p > 0.05). In secondary cardiac index × cognitive diagnosis interaction models, cardiac index and CBF associations were present only in cognitively normal participants and affected a majority of regions assessed with effects strongest in the left (p < 0.0001) and right (p < 0.0001) temporal lobes.

Conclusions:

Among older adults without stroke, dementia, or heart failure, systemic blood flow correlates with cerebral CBF in the temporal lobe, independently of prevalent CVD, but not CVR.

Given metabolic demands, the brain disproportionately receives 12% of cardiac output despite accounting for 2% of total body weight.1 Among older adults, subclinical cardiac output reductions are linked to poorer cognitive performance,2 smaller brain volume,3 white matter hyperintensities,4 and incident dementia, including Alzheimer disease.5 Mechanisms underlying these associations remain elusive. One possible pathway is that subclinical reductions in cardiac output disrupt cerebral blood flow (CBF) homeostasis.

In animal models, cardiac output reductions correspond to lower CBF,6 especially when cerebrovascular injury is present.7 Vascular risk factor and cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevalence increases with age,8 corresponding to compromises in cerebral circulation control mechanisms.9 Lower cardiac output coupled with an aging vasculature may affect static CBF autoregulation in older adults by reducing the ability of distal microvasculature to increase cerebral blood volume to maintain CBF in the presence of cerebral perfusion pressure reductions.10

Among older adults without clinical dementia, stroke, or heart failure, we assess whether cardiac index (cardiac output/body surface area) relates to resting CBF or hypercapnia-induced cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR). By capturing resting CBF in sequence with CVR, we simultaneously evaluate multiple CBF autoregulatory processes. On the basis of prior work,2,3,5 we hypothesize that lower cardiac index will correspond to reduced CBF and reactivity throughout the brain.

METHODS

Study cohort.

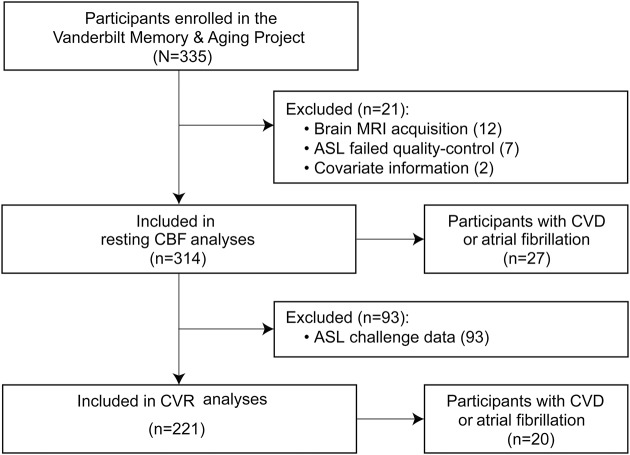

The Vanderbilt Memory & Aging Project is a longitudinal study investigating vascular health and brain aging, enriched for mild cognitive impairment (MCI).11 Inclusion required that participants be ≥60 years of age, speak English, have adequate auditory and visual acuity, and have a reliable study partner. At eligibility, participants underwent medical history and record review, clinical interview (including functional questionnaire and Clinical Dementia Rating12 with the informant), and neuropsychological assessment. Participants were excluded for a cognitive diagnosis other than normal cognition (NC), early MCI,13 or MCI11; MRI contraindication; history of neurologic disease (e.g., stroke); heart failure; major psychiatric illness; head injury with loss of consciousness >5 minutes; and systemic or terminal illness affecting follow-up examination participation. At enrollment, participants completed a comprehensive evaluation, including (but not limited to) fasting blood draw, physical examination, clinical interview, medication review, neuropsychological assessment, echocardiogram, and multimodal brain MRI. Participants were excluded from the current study for missing covariate or brain MRI data (figure 1).

Figure 1. Study inclusion and exclusion details.

Missing data categories are mutually exclusive. Missing covariate data include 1 participant missing left ventricular hypertrophy data and 1 participant missing atrial fibrillation data. Missing ASL challenge data (affecting CVR calculations) include participants unable to wear the nonrebreathing mask or for whom the nonrebreathing mask did not fit properly. Interaction and stratified results for resting CBF models included 164 participants with NC and 124 with MCI. Interaction and stratified results for CVR models included 120 participants with NC and 85 with MCI. ASL = arterial spin labeling; CBF = cerebral blood flow; CVD = cardiovascular disease; CVR = cerebrovascular reactivity; MCI = mild cognitive impairment; NC = normal cognition.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and participant consents.

The protocol was approved by the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained before data collection.

Echocardiogram.

Standard 2-dimensional, M-mode, and Doppler transthoracic echocardiography was performed by a single research sonographer at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Clinical Research Center on a Philips IE33 cardiac ultrasound machine (Philips Medical, Andover, MD). Digital images with measurements were confirmed by board-certified cardiologists (D.K.G., L.A.M.) blinded to clinical information using commercially available software (HeartLab; AGFA Healthcare, Greenville, SC).

Image acquisition and quantification were performed according to American Society of Echocardiography guidelines.14 Left ventricular volume was calculated by the biplane Simpson method. Stroke volume was calculated from the left ventricular outflow tract velocity-time integral and diameter. Cardiac output was calculated as stroke volume times heart rate. Final measurements were from a single cardiac cycle for participants in normal sinus rhythm or the average of 3 cardiac cycles for participants in atrial fibrillation. Cardiac output was indexed to body surface area (cardiac index in liters per minute per meter squared).

Brain MRI.

Participants were scanned at the Vanderbilt University Institute of Imaging Science on a 3T Philips Achieva system (Best, the Netherlands) using 8-channel SENSE reception. T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo (isotropic spatial resolution = 1 mm) images were postprocessed with an established Multi-Atlas Segmentation pipeline15 with parcellation of 10 regions of interest (ROIs), including right and left hemispheres, right and left frontal lobes, right and left temporal lobes, right and left parietal lobes, and right and left occipital lobes.

Pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling (pCASL; postlabeling delay 1.525 seconds, spatial resolution 3 × 3 × 7 mm, repetition time/echo time 4,000/13 milliseconds) assessed CBF (mL blood/100 g tissue/min) with a reproducible protocol.16,17 Data were corrected for motion and baseline drift with the Functional MRI of the Brain Linear Image Registration Tool. Additional postprocessing was completed with MATLAB (MathWorks, Inc, Natick, MA). Whole-brain CBF maps were generated with a sliding window approach. Images were slice-time corrected and converted to absolute CBF units following recommended guidelines.18 The separately acquired M0 image (same geometry but with repetition time 20 seconds) was coregistered to the structural T1-weighted map and fitted to a standard Montreal Neurologic Institute template.19 Transformation matrices were applied to the CBF maps. Region-specific mean resting CBF values were calculated for gray matter ROIs described above.

The pCASL acquisition was repeated with identical parameters during a hypercapnic stimulus to evaluate CVR. A custom nonrebreathing face mask delivered 5% CO2 and 95% medical-grade room air (hypercapnic normoxia). End-tidal CO2 and arterial oxygen saturation were recorded. The first 4 scan volumes during the challenge were removed from processing to allow blood gases to equilibrate. CVR was calculated as percentage change in CBF (from resting CBF due to the induced hypercapnia) normalized by the end-tidal CO2 change (millimeters of mercury). Region-specific mean CVR values were calculated for the 10 gray matter ROIs described above.

Analytical plan.

Systolic blood pressure was the mean of 2 measurements. Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting blood glucose ≥126 mg/dL, hemoglobin A1c ≥6.5%, or oral hypoglycemic or insulin medication use. Medication review determined antihypertensive medication use. Left ventricular hypertrophy was defined on echocardiogram (left ventricle mass index >115 g/m2 in men, >95 g/m2 in women). Self-report atrial fibrillation was corroborated by any one of the following sources: echocardiogram, documented prior procedure/ablation for atrial fibrillation, or medication use for atrial fibrillation. Current cigarette smoking (yes/no within the year before baseline) was ascertained by self-report. Self-reported prevalent CVD with supporting medical record evidence included coronary heart disease, angina, or myocardial infarction (heart failure was a parent study exclusion). Framingham Stroke Risk Profile (FSRP) score was calculated by applying points by sex for age, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication use, diabetes mellitus, current cigarette smoking, left ventricular hypertrophy, CVD, and atrial fibrillation.20 APOE genotyping was performed on whole-blood samples. APOE ε4 carrier (APOE4) status was defined as positive (ε2/ε4, ε3/ε4, ε4/ε4) or negative (ε2/ε2, ε2/ε3, ε3/ε3).

Before analyses, data inspection revealed no evidence of nonlinear effects. Linear regression models with ordinary least-square estimates related cardiac index to resting CBF values and CVR in all gray matter ROIs, including the right and left hemisphere, right and left frontal lobes, right and left temporal lobes, right and left parietal lobes, and right and left occipital lobes. Regions were examined by hemisphere because of asymmetric differences in older cohorts.21 Models were adjusted for age, modified FSRP score (excluding points for age), race/ethnicity, education, APOE4, cognitive diagnosis (NC, early MCI, MCI), and corresponding gray matter ROI to account for CBF reductions due to tissue volume loss (e.g., total gray matter in the left temporal lobe was a covariate for left temporal lobe CBF). To determine whether effects were driven by participants with cognitive impairment, secondary models restricting the sample to participants with NC or MCI tested a cardiac index × diagnosis interaction and then stratified by diagnosis (NC, MCI). These models excluded participants with early MCI because of the small sample size. Sensitivity analyses were performed with the exclusion of participants with atrial fibrillation and prevalent CVD. Significance was set a priori at p < 0.05. Analyses were conducted with R 3.1.2 (www.r-project.org).

RESULTS

Participant characteristics.

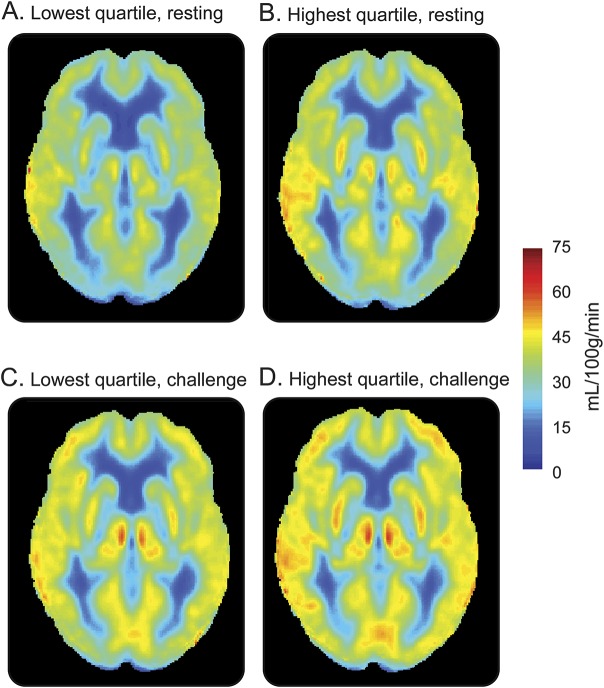

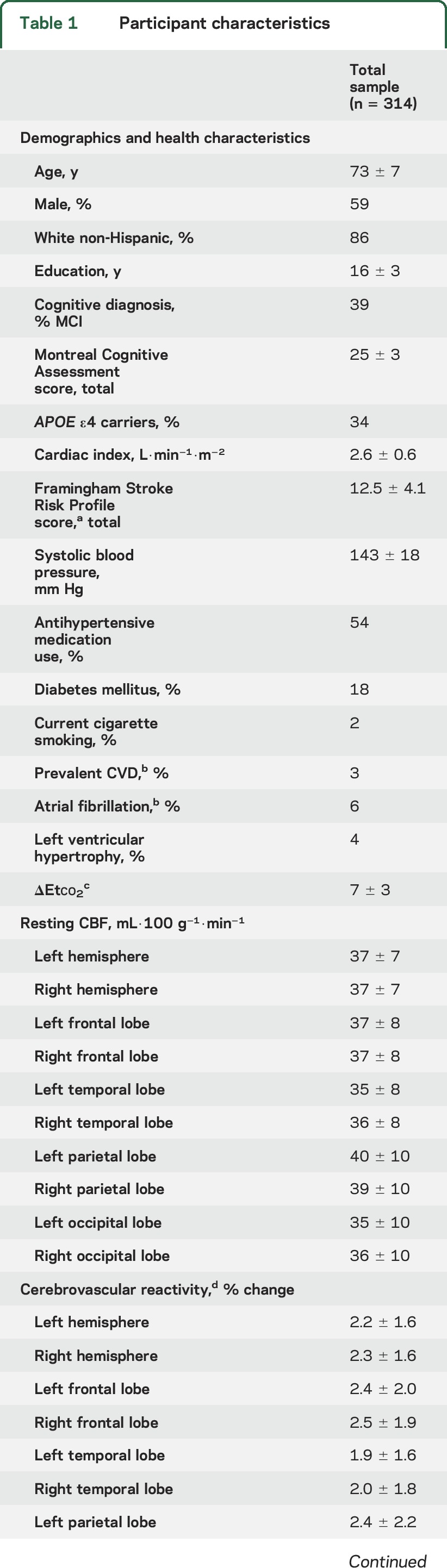

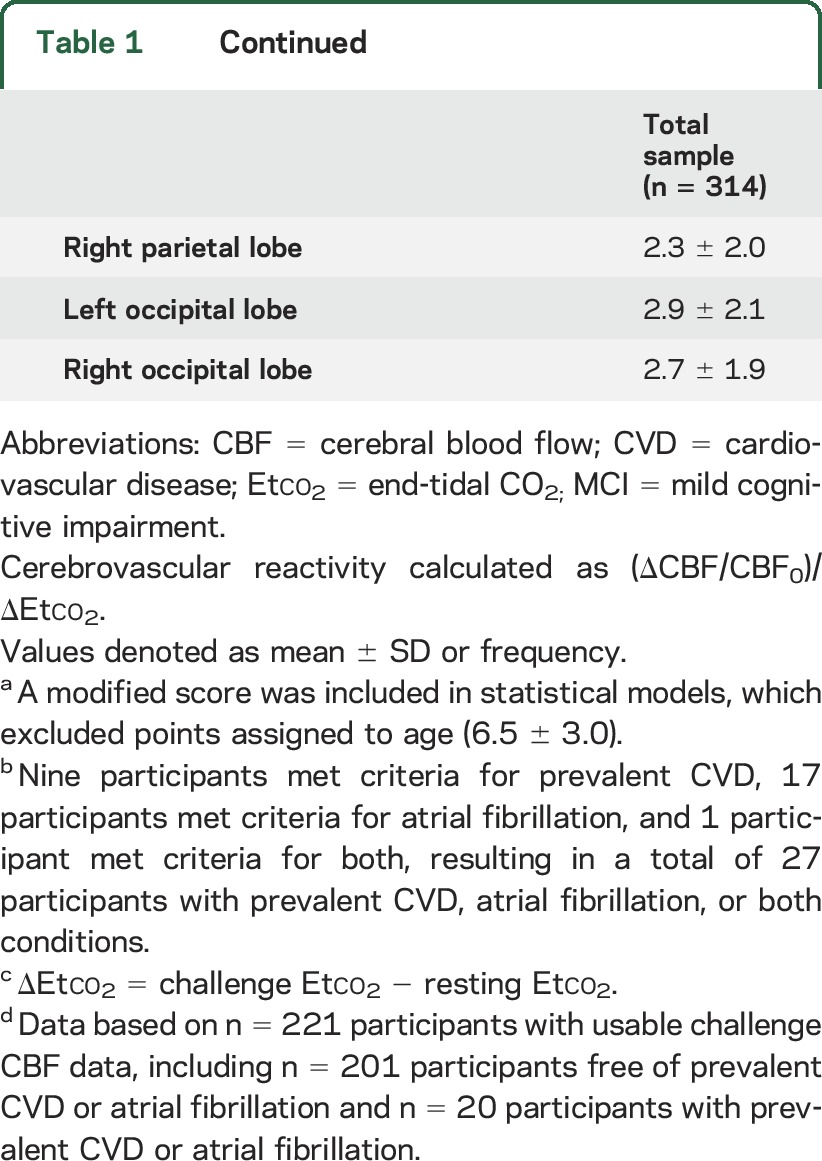

Participants included 314 adults 60 to 92 years of age (73 ± 7 years); 59% were men; and 86% self-identified as non-Hispanic white. Table 1 gives total sample characteristics, and table e-1 at Neurology.org gives characteristics by cognitive diagnosis. Figure 2 provides an illustration of mean resting CBF and challenge CBF maps for participants in the lowest vs highest cardiac index quartile. Participants completing the challenge were more likely female (p < 0.001) and had a lower education level (p < 0.001) but were comparable in age (p = 0.48), race/ethnicity (p = 0.65), cognitive diagnosis (p = 0.41), APOE4 (p = 0.79), and FSRP score (p = 0.95) compared to participants not completing the challenge. Cardiac index was unrelated to end-tidal CO2 during rest (p = 0.55) or challenge (p = 0.20) conditions.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

Figure 2. Resting CBF (A and B) and challenge CBF (C and D) maps for participants in the lowest and highest quartiles of cardiac index.

Low and high cardiac index images were created with the unadjusted group mean image of the Memory & Aging Project participants with CBF analyses (n = 314) or cerebrovascular reactivity analyses (n = 221) in the lowest or highest cardiac index quartile. For illustration purposes only. CBF = cerebral blood flow.

Cardiac index and resting CBF.

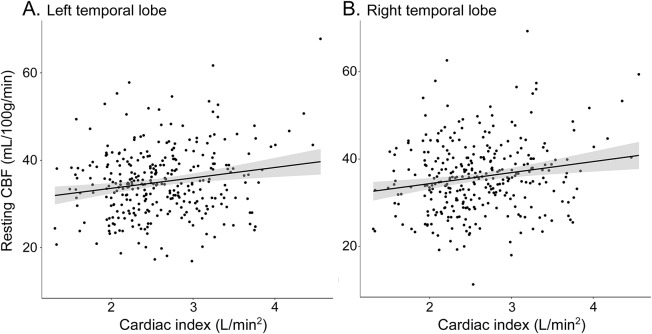

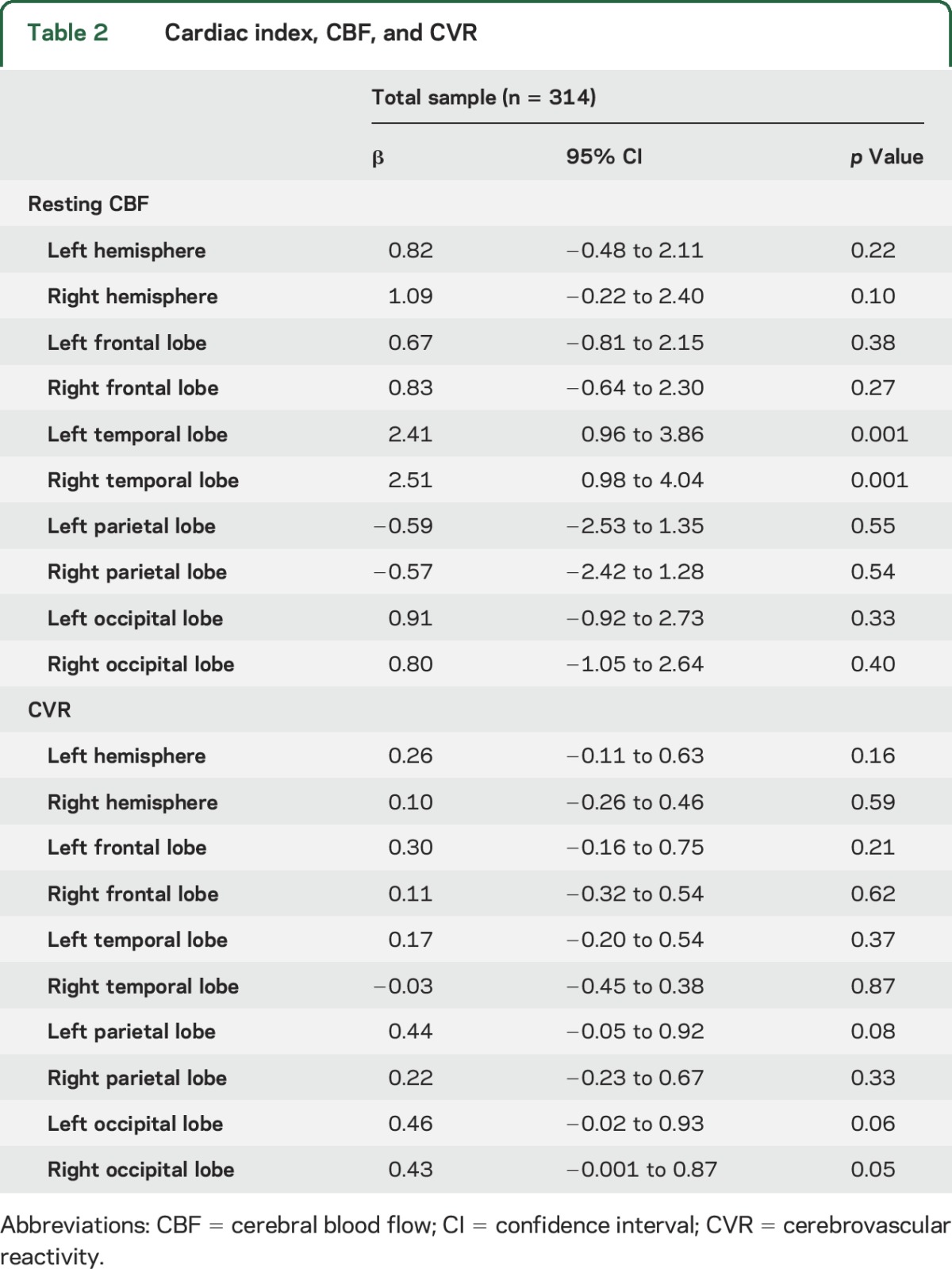

Cardiac index was associated with CBF in the left (p = 0.001) and right (p = 0.001) temporal lobes. Figure 3 provides an illustration. The left temporal lobe CBF was lower on average by 2.4 mL·100 g−1·min−1 per 1-unit decrease in cardiac index (defined as 0.6 L/m2), a magnitude similar to the mean decrease in left temporal lobe CBF with an increase in age of >15 years. The right temporal lobe CBF was lower on average by 2.5 mL·100 g−1·min−1 per 1-unit decrease in cardiac index, a magnitude equivalent to >20 years of advancing age. Cardiac index was unrelated to CBF in the remaining regions (p > 0.10, table 2). In sensitivity analyses excluding participants with atrial fibrillation or prevalent CVD, associations persisted between cardiac index and CBF in the left (β = 2.3, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.8–3.9, p = 0.003) and right (β = 2.5, 95% CI 0.9–4.2, p = 0.003) temporal lobes. Null findings persisted in the remaining regions (p > 0.20).

Figure 3. Cardiac index and resting CBF in the (A) left and (B) right temporal lobes for total sample.

Solid black line reflects unadjusted values of CBF outcomes (y-axis) corresponding to cardiac index (x-axis). Shading reflects 95% confidence interval. CBF = cerebral blood flow.

Table 2.

Cardiac index, CBF, and CVR

In secondary models, the cardiac index × diagnosis interaction was associated with CBF in the right hemisphere (β = −3.1, p = 0.027), right parietal lobe (β = −3.9, p = 0.048), and right occipital lobe (β = −3.8, p = 0.046). The interaction term was modestly associated with CBF in several additional regions, including the left hemisphere (p = 0.063), right frontal lobe (p = 0.066), left temporal lobe (p = 0.07), and left parietal lobe (p = 0.08). Stratified results revealed that associations were exclusively found in participants with NC and present in nearly all regions, although the largest effects were in the left (p = 0.00004) and right (p = 0.0002, table e-2) temporal lobes.

Cardiac index and CVR.

Cardiac index was modestly associated with CVR in the left (p = 0.06) and right (p = 0.05) occipital lobes. Cardiac index was unrelated to CVR for the remaining regions assessed (p > 0.08, table 2). In sensitivity analyses excluding participants with atrial fibrillation or prevalent CVD, cardiac index related to CVR in the left (β = 0.6, 95% CI 0.1–1.1, p = 0.02) and right (β = 0.5, 95% CI <0.1–0.9, p = 0.04) occipital lobes. The remaining sensitivity models were similar to primary models (p > 0.05).

In secondary models, the cardiac index × diagnosis interaction was unrelated to CVR (p > 0.23). Stratified results were similarly null (p > 0.11, table e-2).

DISCUSSION

Among community-dwelling older adults, lower cardiac index was associated with lower resting CBF in the cerebral gray matter, especially the temporal lobes. With the use of comprehensive imaging methods for quantifying systemic and cerebral hemodynamics, associations were statistically independent of key covariates, including vascular risk factors, prevalent CVD, atrial fibrillation, and atrophy. The magnitude of effects for the right and left temporal lobes corresponded to 15 to 20 years of advancing age despite the absence of clinical dementia and stroke in the cohort. Furthermore, associations appeared strongest among participants with NC.

One prior study of 31 nonsmokers free of vascular disease found no association between cardiac index and CBF.22 Methodologic differences may account for the inconsistency in results presented here. For example, the prior work may have been underpowered to detect effects observed here because our cohort was 10 times larger. Alternatively, the prior work used a high-velocity encoding gradient, which may have incorrectly estimated slower flowing blood near the vessel perimeter. The current findings are among the first to document a concurrent association linking cardiac index to cerebral gray matter CBF among aging humans, adding to a growing body of research highlighting the importance of systemic hemodynamics in brain health.2–5,23,24

The mechanism linking systemic blood flow and resting CBF is unclear. A complex autoregulatory control system maintains constant blood supply to the brain in both resting (static) and acute (dynamic) conditions. The dynamic autoregulatory capacity of CBF (in response to rapid cerebral perfusion pressure changes) generally remains intact in aging adults.25,26 Dynamic studies may be less generalizable to static autoregulation, reflecting the steady-state (resting) association between arterial blood pressure and CBF. First, dynamic autoregulation studies rely on experimental manipulation of arterial blood supply to simulate acute orthostatic hypotension (e.g., abrupt postural movements, rapid thigh cuff deflation). Second, CBF is typically estimated with transcranial Doppler quantifying flow velocity in the large arterial supply rather than cerebral tissue perfusion. Such approaches are susceptible to methodologic heterogeneity, especially with concomitant cerebrovascular disease.27,28 Therefore, the dynamic autoregulation literature may not fully address the complex myogenic, metabolic, and neurogenic mechanisms involved in cerebral autoregulation.

Patients with heart failure experience CBF reductions29,30 that normalize after transplantation,31 suggesting that mechanisms underlying static cerebral autoregulation may be compromised with severe cardiac dysfunction.29,30 In the absence of heart failure (like the cohort here), these mechanisms may be less effective in elders with a lifetime exposure to suboptimal vascular risk factors.32 Such exposure contributes to compromised vascular compliance33 and blood-brain barrier integrity.34 These subtle compromises may account for our results suggesting that autoregulatory mechanisms are vulnerable in aging, even before the onset of cognitive impairment, an important observation for the field.

Given our cross-sectional methods, our findings could also be explained by a third variable unaccounted for in our analyses, creating an epiphenomenon or reverse causation between cardiac index and CBF. One possibility is compromise to the sympathetic nervous system responsible for hemodynamic control throughout the body,35 such as angiotensin II signaling dysfunction, could affect systemic fluid homeostasis, blood volume, and cerebral circulation.36 Future research examining potential mechanisms is warranted, especially research using longitudinal methods.

Cardiac index and resting CBF associations were localized to the temporal lobes in the entire cohort. In stratified models, the associations were strongest in the participants with NC and more anatomically diffuse with the largest effects in the temporal lobes. The temporal lobes may be especially vulnerable because of a less extensive network of collateral blood flow sources.37 Alternatively, the pCASL perfusion signal may be slice dependent in multislice echo-planar imaging acquisitions (as used here), yielding lower label decay and shorter postlabeling delays in bottom slices (e.g., temporal lobe) relative to top slices when images are acquired in ascending order.38 Incrementing the postlabeling delay time in a slice-dependent fashion during postprocessing accounts for this effect, and visual inspection of quantified CBF maps revealed no evidence of signal decay. Another possibility is that age-related CBF changes account for the pattern because age-dependent breakdown of the blood-brain barrier has been recently reported in the human hippocampus,34 where Alzheimer disease pathology first evolves.39 We previously reported that lower cardiac index levels correspond to an increased risk of incident dementia, especially Alzheimer disease.5 Therefore, subtle compromises in static autoregulatory mechanisms within the cerebral microcirculation may have age-related regional variability or early pathologic changes, placing temporal structures at greatest risk.

We observed differences between cardiac index and resting CBF vs CVR. In sensitivity analyses, lower cardiac index related to less reactivity in the posterior cortex, but results were not significant in primary models or stratified results. Furthermore, cardiac index is unrelated to end-tidal CO2 during resting and challenge conditions. Our results suggest a mismatch between significant resting CBF and null CVR across different cardiac index values, offering an interesting perspective regarding the effect of peripheral vascular health on cerebrovascular functioning. Collectively, results suggest that the CBF observation may be attributable to alterations in tissue physiology rather than a fundamental impairment in vascular compliance. However, other factors may contribute to these null reactivity results, including insufficient power (with fewer participants in the reactivity analyses because of difficulties wearing the nonrebreathing mask). Alternatively, it is plausible that the vascular challenge investigated here (5% CO2) was insufficient to exhaust cerebrovascular reserve. A different finding might be possible with a larger stimulus (6%–10% CO2), although these stimuli are less comfortable for participants and atypical in most CVR studies. Another explanation is that cardiac function was captured by echocardiogram in a separate session, so it is unknown whether cardiac output changed in response to the vasodilatory challenge. Lower cardiac index may affect static cerebrovascular function even when dynamic autoregulatory processes remain intact, but our results require replication to confirm the absence of association between cardiac index and CVR.

Our study has several strengths, including using a well-established method for noninvasively assessing cerebral perfusion, evaluating different perfusion conditions, and using a vasodilatory stimulus (CO2) to assess CVR. Additional strengths include comprehensive ascertainment of potential confounders, a reliable imaging technique for quantifying cardiac output (reflecting the clinical standard), stringent quality control procedures, and use of a core laboratory for processing cardiac and CBF measurements by technicians who were clinically blinded.

Despite these strengths, several limitations should be considered. First, results are cross-sectional and cannot speak to causality, raising the possibility of reverse causation. Longitudinal studies are needed to understand the temporal nature of associations reported here. Second, our sample included predominantly white, well-educated, healthy older adults. Generalizability to other races, ethnicities, ages, or adults with poorer health is unknown. We speculate that in a less healthy cohort with greater vascular risk factors or more compromised cardiac function, the associations reported here would likely be stronger. Future research is needed to test this hypothesis. Third, partial volume effects inherent to the pCASL technique may have affected our CBF estimates. We previously reported that lower cardiac index is associated with smaller brain volume,3 so we adjusted for regional co-occurring atrophy using a multi-atlas approach to improve segmentation accuracy and to minimize partial volume effects. Nevertheless, it is possible that partial volume effects confounded results. Another limitation is that reactivity models were based on a smaller sample (n = 221) because some participants were unable to wear the face mask. In addition, cerebral hemodynamic abnormalities in MCI could drive spurious results.40 However, our primary observations remained significant when analyses were restricted to a carefully characterized sample of cognitively normal older adults, suggesting that hemodynamic abnormalities in MCI did not account for our findings. Finally, multiple comparisons could result in false-positive findings. Bonferroni-corrected results (corrected α = 0.005) would still suggest that lower cardiac index is associated with lower CBF in the temporal lobes, particularly among participants with NC. Nevertheless, our results require replication.

Among older adults free of clinical stroke, dementia, and heart failure, lower cardiac index relates to poorer CBF, especially in the temporal lobes, independently of concurrent cardiovascular risk factors, CVD, or atrial fibrillation. Associations appear strongest among participants with NC. Further investigation into mechanisms linking cardiac index and regional CBF is warranted to identify primary prevention targets or therapeutic interventions.

GLOSSARY

- CBF

cerebral blood flow

- CI

confidence interval

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- CVR

cerebrovascular reactivity

- FSRP

Framingham Stroke Risk Profile

- MCI

mild cognitive impairment

- NC

normal cognition

- pCASL

pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling

- ROI

region of interest

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Angela L. Jefferson: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, study supervision, manuscript composition. Dandan Liu: analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript composition. Deepak K. Gupta: acquisition of data, manuscript composition. Kimberly R. Pechman: analysis and interpretation of data, study supervision, manuscript composition. Jennifer M. Watchmaker: analysis and interpretation of data. Elizabeth A. Gordon: analysis and interpretation of data, study supervision, manuscript composition. Swati Rane: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript composition. Susan P. Bell and Lisa A. Mendes: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data. L. Taylor Davis: analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript composition. Katherine A. Gifford: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, study supervision, manuscript composition. Timothy J. Hohman: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, study supervision, manuscript composition. Thomas J. Wang: analysis and interpretation of data. Manus J. Donahue: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, study supervision, manuscript composition.

STUDY FUNDING

This research was supported by Alzheimer's Association IIRG-08-88733 (A.L.J.), R01-AG034962 (A.L.J.), R01-NS100980 (A.L.J.), K24-AG046373 (A.L.J.), Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award in Aging K23-AG045966 (K.A.G.), Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award in Aging K23-AG048347 (S.P.B.), K12-HD043483 (K.A.G., S.P.B., T.J.H.), K01-AG049164 (T.J.H.), K12-HL109019 (D.K.G.), R01-NS078828 (M.J.D.), R01-NS097763 (M.J.D.), American Heart Association 14GRNT20150004 (M.J.D.), UL1-TR000445 (Vanderbilt Clinical Translational Science Award), and the Vanderbilt Memory & Alzheimer's Center.

DISCLOSURE

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Williams LR, Leggett RW. Reference values for resting blood flow to organs of man. Clin Phys Physiol Meas 1989;10:187–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jefferson AL, Poppas A, Paul RH, Cohen RA. Systemic hypoperfusion is associated with executive dysfunction in geriatric cardiac patients. Neurobiol Aging 2007;28:477–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jefferson AL, Himali JJ, Beiser AS, et al. Cardiac index is associated with brain aging: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2010;122:690–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jefferson AL, Tate DF, Poppas A, et al. Lower cardiac output is associated with greater white matter hyperintensities in older adults with cardiovascular disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:1044–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jefferson AL, Beiser AS, Himali JJ, et al. Low cardiac index is associated with incident dementia and Alzheimer disease: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2015;131:1333–13339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wanless RB, Anand IS, Gurden J, Harris P, Poole-Wilson PA. Regional blood flow and hemodynamics in the rabbit with adriamycin cardiomyopathy: effects of isosorbide dinitrate, dobutamine and captopril. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1987;243:1101–1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tranmer BI, Keller TS, Kindt GW, Archer D. Loss of cerebral regulation during cardiac output variations in focal cerebral ischemia. J Neurosurg 1992;77:253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jousilahti P, Vartiainen E, Tuomilehto J, Puska P. Sex, age, cardiovascular risk factors, and coronary heart disease: a prospective follow-up study of 14 786 middle-aged men and women in Finland. Circulation 1999;99:1165–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farkas E, Luiten PG. Cerebral microvascular pathology in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Prog Neurobiol 2001;64:575–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jordan LC, Gindville MC, Scott AO, et al. Non-invasive imaging of oxygen extraction fraction in adults with sickle cell anaemia. Brain 2016;139:738–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Demen 2011;7:270–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993;43:2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aisen PS, Petersen RC, Donohue MC, et al. Clinical core of the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative: progress and plans. Alzheimer's Dement 2010;6:239–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2015;28:1–39.e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asman AJ, Landman BA. Non-local statistical label fusion for multi-atlas segmentation. Med Image Anal 2013;17:194–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donahue MJ, Hussey E, Rane S, et al. Vessel-Encoded Arterial Spin Labeling (VE-ASL) reveals elevated flow territory asymmetry in older adults with substandard verbal memory performance. J Magn Reson Imaging 2014;39:377–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donahue MJ, Faraco CC, Strother MK, et al. Bolus arrival time and cerebral blood flow responses to hypercarbia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2014;34:1243–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alsop DC, Detre JA, Golay X, et al. Recommended implementation of arterial spin-labeled perfusion MRI for clinical applications: a consensus of the ISMRM perfusion study group and the European consortium for ASL in dementia. Magn Reson Med 2015;73:102–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Smith SM. FSL. Neuroimage 2012;62:782–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D'Agostino RB, Wolf PA, Belanger AJ, Kannel WB. Stroke risk profile: adjustment for antihypertensive medication: the Framingham study. Stroke 1994;25:40–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi F, Liu B, Zhou Y, Yu C, Jiang T. Hippocampal volume and asymmetry in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease: meta-analyses of MRI studies. Hippocampus 2009;19:1055–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henriksen OM, Jensen LT, Krabbe K, Larsson HB, Rostrup E. Relationship between cardiac function and resting cerebral blood flow: MRI measurements in healthy elderly subjects. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2014;34:471–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jefferson AL, Himali JJ, Au R, et al. Relation of left ventricular fraction to cognitive aging (from the Framingham Heart Study). Am J Cardiol 2011;108:1346–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jefferson AL, Holland CM, Tate DF, et al. Atlas-derived perfusion correlates of white matter hyperintensities in patients with reduced cardiac output. Neurobiol Aging 2011;32:133–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lipsitz LA, Mukai S, Hamner J, Gagnon M, Babikian V. Dynamic regulation of middle cerebral artery blood flow velocity in aging and hypertension. Stroke 2000;31:1897–1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carey BJ, Panerai RB, Potter JF. Effect of aging on dynamic cerebral autoregulation during head-up tilt. Stroke 2003;34:1871–1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Demolis P, Tran Dinh YR, Giudicelli JF. Relationships between cerebral regional blood flow velocities and volumetric blood flows and their respective reactivities to acetazolamide. Stroke 1996;27:1835–1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minhas PS, Menon DK, Smielewski P, et al. Positron emission tomographic cerebral perfusion disturbances and transcranial Doppler findings among patients with neurological deterioration after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery 2003;52:1017–1022; discussion 1022–1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gruhn N, Larsen FS, Boesgaard S, et al. Cerebral blood flow in patients with chronic heart failure before and after heart transplantation. Stroke 2001;32:2530–2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi BR, Kim JS, Yang YJ, et al. Factors associated with decreased cerebral blood flow in congestive heart failure secondary to idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2006;97:1365–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Massaro AR, Dutra AP, Almeida DR, Diniz RV, Malheiros SM. Transcranial Doppler assessment of cerebral blood flow: effect of cardiac transplantation. Neurology 2006;66:124–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association's strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation 2010;121:586–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fonck E, Feigl GG, Fasel J, et al. Effect of aging on elastin functionality in human cerebral arteries. Stroke 2009;40:2552–2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montagne A, Barnes SR, Sweeney MD, et al. Blood-brain barrier breakdown in the aging human hippocampus. Neuron 2015;85:296–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cencetti S, Lagi A, Cipriani M, Fattorini L, Bandinelli G, Bernardi L. Autonomic control of the cerebral circulation during normal and impaired peripheral circulatory control. Heart 1999;82:365–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saavedra JM, Benicky J, Zhou J. Mechanisms of the anti-ischemic effect of angiotensin II AT( 1 ) receptor antagonists in the brain. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2006;26:1099–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liebeskind DS. Collateral circulation. Stroke 2003;34:2279–2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deibler AR, Pollock JM, Kraft RA, Tan H, Burdette JH, Maldjian JA. Arterial spin-labeling in routine clinical practice, part 1: technique and artifacts. Am J Neuroradiol 2008;29:1228–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol 1991;82:239–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beishon L, Haunton VJ, Panerai RB, Robinson TG. Cerebral hemodynamics in mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review. J Alzheimer's Dis 2017;59:369–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]