Abstract

A large number of human diseases are caused by expansion of repeat sequences—typically trinucleotide repeats—within the respective disease genes. The abnormally expanded sequence can lead to a variety of effects on the consequent gene: sometimes the gene is silenced, but in many cases the expanded repeat sequences confer toxicity to the mRNA and, in the case of polyglutamine diseases, to the encoded protein. This article highlights mechanisms by which the mRNAs with abnormally expanded repeats can confer toxicity leading to neuronal dysfunction and loss. Greater understanding of these mechanisms will provide the foundation for therapeutic advances for this set of human disorders.

REPEAT EXPANSION DISEASES

Trinucleotide repeat sequences within mRNAs, predominantly CNG sequences (where N refers to U, A, or G), are a motif that is prominent in neurological diseases (Box 1). Expansion of CNG repeat sequences can cause dramatic effects on the expression and/or stability of the host mRNA, leading to disruption in cellular and protein functions, resulting in neuronal degeneration and eventual cell loss. Moreover, the potential effects of a disrupted mRNA can be well beyond just affecting the protein encoded: while the activity of mRNA was traditionally viewed as to faithfully deliver the message of the DNA sequence to the cytoplasm for protein expression, evidence in the past decade shows that select sequences in mRNA molecules have critical functions important to gene function regulation. For example, common regulatory elements in the untranslated regions of an mRNA—the 5′ and 3′ UTRs—can play important roles in mRNA stability, localization, and protein translation. The RNA world is vastly more complex than previously thought, as alteration of proper RNA sequences can lead to abnormal RNA-protein interactions, alteration of protein translation events, and activation of a variety of pathways, such as RNA interference (RNAi) and protein misfolding pathways.

BOX 1. Repeat Expansion Diseases.

Expanded repeat diseases are a set of human disorders caused by the expansion of nucleotide repeat sequences within the target gene. Depending on the location of the repeat, these diseases can be further classified into two groups: those that are caused by expansion of a repeat sequence within the open reading frame—for example, the expansion of CAG repeats encoding glutamine defines the polyQ diseases; and those that are caused by expansion of nucleotide repeat tracts in the non-coding region. To date expansion of many types of repeat sequences are found associated with neurological disorders, the majority of which are triplet repeats with the sequence CNG (where N refers to T, A, or G). Expansion of other repeat sequences such as CCTG and ATTCT are also found as pathological causes. Although each nucleotide repeat disease has distinctive clinical features, neurological symptoms are the most common defects observed in the majority of situations. In addition, the severity of the diseases is typically associated with the repeat length. The longer the repeat is, the more severe the symptoms. The repeat sequences also show somatic and germline instability, the latter of which underlies the phenomenon of anticipation, whereby the symptoms of disease occur with earlier onset and greater severity in successive generations due to expansion of the repeat sequence.

Here we discuss some common mechanisms by which expansion of a trinucleotide repeat tract within an mRNA disrupts protein and cellular functions, which can lead to disease symptoms. Since the number of neurological diseases associated with RNA toxicity is increasing, understanding how expanded repeat RNAs confers neurotoxicity will be critical to developing effective treatments for these diseases. Such studies may also provide insight into fundamental mechanisms that regulate neuronal activity and maintenance. This review emphasizes key pathways and mechanisms of toxicity at the level of RNAs that have received attention recently; for other reviews emphasizing different aspects of trinucleotide diseases, see [1–3].

TOXIC EFFECTS OF THE EXPANDED REPEAT RNA

At least six neurological or neurodegenerative diseases are associated with toxicity of RNA due to the expansion of repeat sequences within the respective genes (Table 1). For some of these disorders, such as myotonic dystrophy 1 (DM1) and Fragile X-Associated Tremor Ataxia Syndrome (FXTAS), dominant toxicity of the RNA is thought to be the primary cause of disease symptoms [2]. For others, such as several spinocerebellar ataxias (SCA3, 8, 10), and Huntington disease-like 2 (HDL2), emerging evidence suggests that the expanded repeat RNA contributes to disease symptoms, with the precise pathologic mechanisms the focus of current study [1]. Nevertheless, biochemical, genetic, and pathological studies of these diseases have revealed some common pathways by which an expanded repeat in an RNA can induce cellular toxicity. These include dominant effects on protein functions, RNAi pathways, and cell-signaling.

Table 1.

Select neurological diseases associated with expanded repeat RNA toxicity

| Disease | Repeat type | Location of the repeat | Normal repeat length | Disease repeat length | Main clinical symptoms | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diseases caused by RNA toxicity | ||||||

| DM1 | CTG | 3′UTR | 5–37 | 50– >1000 | muscle weakness, mental retardation | [44–46] |

| DM2 | CCTG | Intron | 10–26 | 75– >1,1000 | Muscle weakness | [47, 48] |

| FXTAS | CGG | 5′UTR | 6–60 | 60–200 | tremor/ataxia, parkinsonism, cognitive deficits | [49] |

| Diseases with RNA toxicity as a component | ||||||

| SCA3 | CAG | protein –encoding region | 13–36 | 61–84 | ataxia and parkinsonism | [50] |

| SCA8 | CTG | non-coding RNA | 16–34 | >74 | ataxia and slurred speech | [51, 52] |

| SCA12 | CAG | Not determined | 7–45 | 55–78 | ataxia and seizures | [53] |

| HDL2 | CTG | Not determined | 7–28 | 66–78 | chorea, cognitive deficits | [54] |

Dominant effects on protein function

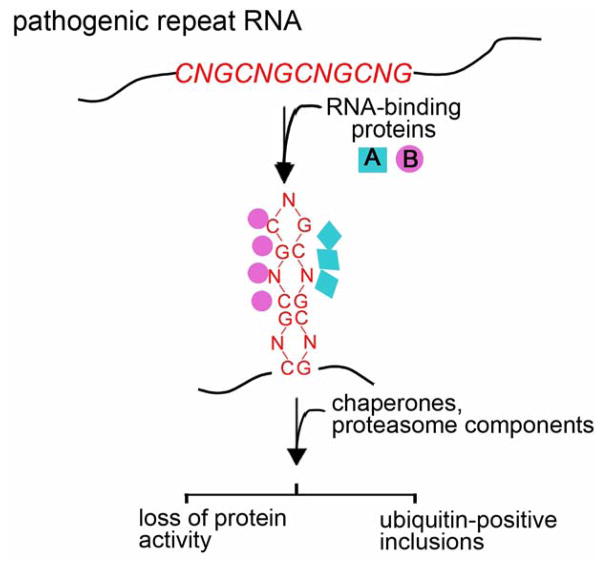

In a number of situations, expansion of the nucleotide repeat tract in the disease gene mRNA has been found to lead to aberrant RNA-protein interactions, such that select proteins that bind to the sequence become sequestered. Such abnormal interactions can disrupt the normal functions of the proteins that become bound, resulting in loss-of-activity of those RNA-binding proteins. Abnormal RNA-protein interactions may also lead to disrupted protein conformation, altering chaperone and proteasome localization (Figure 1). Therefore RNAs with expanded repeat sequences can have dominant effects on a number of critical cellular functions, leading to dysfunction through distinct pathways.

Figure 1.

Dominant effects of a pathogenic repeat RNA on protein functions. Expansion of a trinucleotide repeat within an RNA can cause aberrant RNA-protein interactions. This could sequester proteins such as MBNL1 and Pur α (represented by proteins A and B in the figure), leading to their depletion and loss of their normal functions. This binding could also lead to abnormal RNA-protein complexes, which form inclusions and may affect protein quality control pathways, for example, inducing localization of chaperone and proteasome components.

RNA-binding proteins

MBNL and CUGBP1

Several RNA-binding proteins have been identified as key regulators in RNA-mediated diseases. Some of these proteins interact with a range of repeat sequences, such as muscleblind-like (MBNL) and CUG-binding proteins (CUGBP1), while others interact with select repeat sequences, such as Pur α (Table 2).

Table 2.

Substrate specificity of repeat RNA-binding proteins.

| Repeat RNA | CUG | CAG | CGG | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBNL1a | High affinity | High affinity | Not determined. | [17] |

| CUGBP1 | Direct interaction | No interaction | Interaction requires hnRNPA2/B1 | [55] |

| hnRNPA2/B1 | No interaction | No interaction | Direct interaction | [21] |

| Pur α | No interaction | No interaction | Direct interaction | [22] |

MBNL1 has similar Kd for binding of (CUG)54 (Kd = 5.3 ± 0.6 nM) and (CAG)54 (Kd = 11.2 ± 1.5 nM) in filter-binding assays, which is similar to the Kd (6.6 ± 0.5 nM ) of MBNL1 in binding to the splicing target TNNT3 [17].

MBNL1 and CUGBP1 are key contributors to symptoms observed in DM1 patients [2, 3]. Both proteins are splicing regulators that are differentially affected by the pathogenic expanded CUG repeat RNA: long CUG repeats lead to decreased MBNL activity and increased CUGBP1 activity. This results in mis-splicing of a number of target mRNAs, such as the insulin receptor (IR), chloride channel (CLCN-1), and cardiac troponin T (TNNT2) [2, 3], contributing to different aspects of DM1 symptoms. For example, generation of the non-muscle isoform of the IR through exclusion of exon 11 is thought to be the molecular basis for the insulin resistance symptoms observed in DM1. Since MBNL1 promotes inclusion of exon 11 in IR splicing [4], and CUGBP1 causes exclusion of exon 11 [4, 5], a combined effect of decreased MBNL1 and increased CUGBP1 activity induced by expanded CUG repeat RNA promotes formation of the aberrant isoform of the IR in disease. The ultimate effect is generally that normal developmental-to-adult splicing switches fail to occur for these genes, leading to disrupted function.

Interestingly, pathogenic CUG repeat RNA regulates MBNL1 and CUGBP1 activities through different mechanisms, which also reflects the scope of distinct cellular pathways in which a repeat RNA can disrupt function. Since MBNL1 has higher affinity for expanded CUG repeat RNA than with normal RNA, abnormal interactions between expanded CUG repeat RNA and MBNL1 are thought to result in formation of RNA-protein complexes that deplete MBNL1 leading to a loss of its normal cellular functions. On the other hand, CUGBP1 has similar affinity for CUG repeats of different lengths [2]. Recent studies suggest that CUGBP1 levels are increased by expanded CUG repeat RNA through activation of protein kinase C (PKC), rather than through direct interactions with the CUG repeat RNA [6].

Key muscle symptoms of DM1 are recapitulated in mouse models expressing a pathogenically expanded CUG repeat RNA, including abnormal muscle structure, sequestration of MBNL1 and increased levels of CUGBP1 [7, 8]. The roles of MBNL1 and CUGBP1 in DM1 pathogenesis are further emphasized by mouse models that knock-out MBNL1 or upregulate CUGBP1. These mice recapitulate components of DM1 symptoms, such as abnormal muscle structure and misregulated splicing of CLCN-1 and TNNT2 mRNAs in skeletal muscle and heart [9, 10]. These findings suggest that an expanded CUG repeat RNA induces toxicity through dominant effects on MBNL1 and CUGBP1 proteins, independent of gene context. They also raise the possibility that disruption of aberrant RNA-protein interactions that occur in the disease situation could be an approach for mitigating DM1 symptoms.

Initial studies to test such a possibility showed that replenishing MBNL1 levels in skeletal muscle can rescue mis-splicing deficits of several pre-mRNAs, such as CLC1 and TNNT2, as well as alleviate muscle symptoms in mice expressing an expanded CUG repeat RNA [11]. More recent studies show that injection of anti-sense CAG oligonucleotides [12, 13], or a chemical compound pentamidine [14] that can bind the expanded CUG repeat RNA, can block the pathological RNA interactions with MBNL1. This leads to a replenishment of MNBL1 levels in cells, and suppresses both the abnormal pre-mRNA splicing defects and muscle symptoms in mouse models.

Although the above findings are largely based on studies in muscle, there is evidence indicating that similar mis-splicing events occur in neurons. For example, abnormal splicing of genes that are important for brain function, such as tau and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (e.g., NMDAR1), occurs in DM1 and SCA8 brain tissues [15, 16]. Interestingly, a number of targets inappropriately spliced in DM1 are key genes in Alzheimer’s disease, such as tau and APP, which underscores potential commonalities among different diseases. Taken together, these findings suggest that suppression of the dominant RNA toxicity in DM1 by preventing the abnormal protein-RNA interactions could be an intervention site for this and potentially other expanded repeat neurological diseases with a toxic RNA component.

Commonalities with other types of RNA toxicity

MBNL1 and CUGBP1 also interact with other types of repeat RNA sequences in addition to CUG repeats. For instance, in vitro biochemical studies suggest that MBNL1 has similar affinity for both CUG and CAG repeat RNA [17]. Moreover, CAG-repeat RNA has also been found to have pathogenicity in studies stemming from the unanticipated isolation of the fly counterpart of MBNL1, Mbl, as a modulator of neurotoxicity of pathogenic polyglutamine (polyQ) protein [18]. PolyQ diseases are due to CAG repeat expansions within the open reading frame of the respective genes, and have classically been thought to be caused solely by dominant toxicity of the protein due to the expanded polyQ tract. Study of the potential role of Mbl in polyQ toxicity lead to the unexpected finding that an expanded CAG repeat RNA may have toxicity that contributes to polyQ disease symptoms [18]. The precise contributions of the CAG repeat RNA and the mutant polyQ protein to the pathology will be interesting to define, and this result suggests that blocking RNA toxicity is a potential therapeutic target in treating polyQ diseases as well as CUG-repeat diseases. Identification of additional CAG RNA-binding proteins may provide insight into novel pathological aspects of polyQ disease. MBNL1 is also found in the abnormal protein inclusions in brain tissues of the CGG expansion disease FXTAS [19], raising the possibility that MBNL proteins also interact with expanded CGG repeat RNA. Recent studies also suggest that MBNL may be recruited to RNA stress granules [20], raising the possibility of additional functions of the protein beyond splicing regulation. Thus, MBNL may have general roles in RNA metabolism, in addition to being a splicing regulator, and these various functions may contribute to several neurodegenerative situations.

Studies from a Drosophila model of CGG RNA toxicity suggest that CUGBP1 also regulates CGG RNA-mediated degeneration. However, unlike interactions with CUG-repeat RNA noted above, CUGBP1 interacts with the CGG-repeat RNA through another RNA-binding protein, hnRNP A2/B1 [21]. Thus, like MBNL1, CUGBP1 may have multiple activities that contribute to RNA toxicity in situations of expanded repeat sequence. Further studies of these functions may reveal common aspects and distinct specificities in the various types of repeat RNA-mediated diseases.

Other RNA-binding proteins have been found to have more specific interactions with a single type of nucleotide repeat RNA. For example, Pur α and hnRNP A2/B1 were identified as proteins that selectively interact with CGG, but not CAG or CUG repeat RNAs [21, 22]. Evidence from FXTAS models suggests that expanded CGG repeat RNAs recruit Pur α into nuclear inclusions and prevent its normal function [22]. Consistent with this hypothesis, mice lacking Pur α develop neurological symptoms including ataxia [23]. Therefore loss-of-function of Pur α may contribute to FXTAS pathology.

Taken together, the above findings indicate that expanded repeat RNAs of disease genes can cause dominant effects on a variety of protein functions due to altered RNA-protein interactions. Initial studies in mouse models of DM1 suggest that blocking such aberrant interactions can release sequestered proteins such as MBNL1 and restore normal protein function, thereby reducing RNA toxicity. Thus targeting such interactions could be a promising intervention site for DM1 as well as other diseases with RNA-based toxicity.

Proteins involved in quality control pathways

In addition to a direct effect on RNA-binding proteins, RNA with expanded repeat sequences could have indirect effects on protein folding and degradation pathways. For example, although the expansion of nucleotide repeats in the DM1 and FXTAS associated genes does not alter the sequence of the encoded proteins, ubiquitinated inclusions that may contain proteasome components or chaperones are found in disease tissues [16, 19]. Similar inclusions are found in fly models that express non-coding CGG repeats [22]. These findings raise the possibility that long repeat RNA tracts in these situations lead to a disruption of proper protein quality control pathways, which may in part contribute to disease pathogenesis.

Currently it is thought that aberrant interactions between expanded repeat RNA and proteins could stabilize both the RNA and the proteins, resulting in abnormal protein accumulation into inclusions. Such inclusions may induce chaperones, proteasome components, and ubiquitin to degrade abnormally accumulated proteins [16, 22]. As abnormal protein accumulation is a hallmark of many protein-based neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and polyQ diseases [24], this commonality raises the idea that shared pathological pathways may contribute to shared symptoms of RNA-mediated and protein-mediated neurological disorders. Thus approaches to relieve protein-mediated toxicity, such as upregulation of chaperones, may be applicable to situations of RNA-mediated toxicity. Consistent with this hypothesis, upregulation of Hsc70 has been found to protect against CGG repeat RNA toxicity in Drosophila [25], just like upregulation of Hsp70 was found to protect against polyQ and Parkinson’s diseases [26, 27].

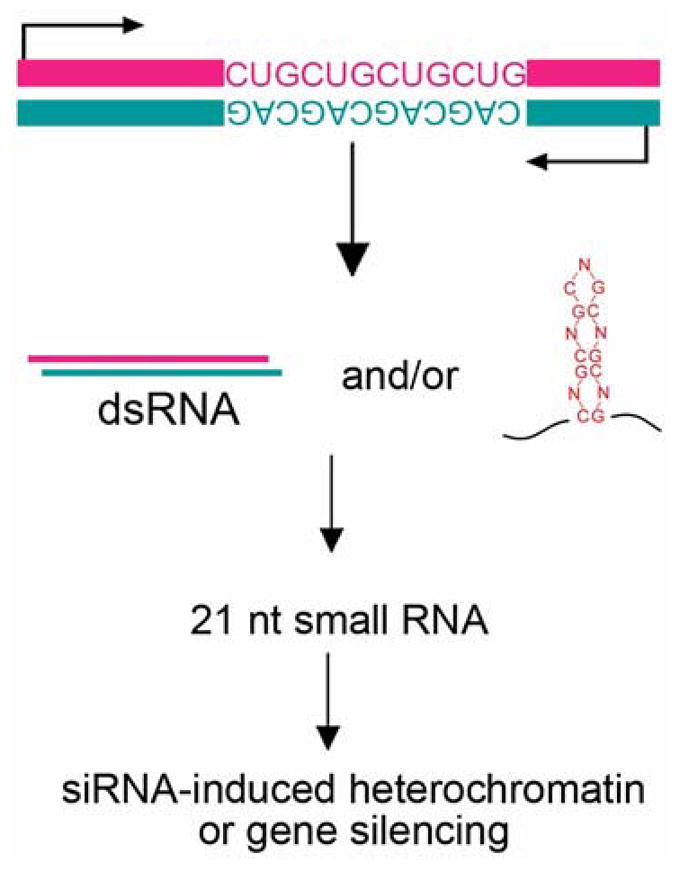

Sense/anti-sense transcripts and interactions

Expanded repeat RNAs could have complex interactions and effects due to the presence of both sense and anti-sense transcripts bearing the repeat sequence (Figure 2). Currently it is thought that many mammalian genes may generate transcripts from both strands [28, 29]. To date, at least three triplet repeat disease loci are found to generate anti-sense transcripts that cover the repeat region. This raises the possibility that disease symptoms may not only be caused by gain-of-function effects due to the classically studied sense RNA, but also by effects of the expanded repeat within the anti-sense transcript. That is, if the sense transcript accumulates to cause dominant toxicity by sequestering proteins or activating pathways, then the anti-sense transcript may also have such effects. Moreover, there may be additional effects induced by double stranded RNA (dsRNA) formed by pairing between the two transcripts when they are co-expressed or accumulate aberrantly in disease. For example, anti-sense transcripts are detected at the DM1 locus and are thought to form dsRNA with the sense transcript. The dsRNA is found to be processed into small RNAs which induce RNAi-triggered local heterochromatin formation [30]. In another situation, the SCA8 disease locus is found to express both an expanded CUG repeat RNA and an anti-sense CAG repeat RNA [31]. The CAG repeat RNA appears to be translated into a polyQ protein. Thus, SCA8 symptoms may be a mixture of toxicity conferred by the CUG repeat RNA, and by the CAG-repeat RNA encoded polyQ protein. The precise contributions of each mechanism to SCA8 symptoms will be interesting to clarify. Recent studies also report transcription of anti-sense mRNA bearing the CGG repeat at the FXTAS locus, raising the possibility that sense/anti-sense transcripts may form dsRNA structures that contribute to symptoms in this disorder as well [32].

Figure 2.

Expanded trinucleotide repeat RNA could induce dominant effects through the generation of small RNAs. In disease loci where anti-sense RNA that contains the repeats is generated, interactions between sense and anti-sense transcripts could form dsRNA and be a substrate recognized by the RNAi pathway and processed by into small RNAs. Alternatively, some studies suggest that the expanded repeat RNA hairpin itself can be processed into small RNAs. Small RNAs generated may target the expression of other genes with sequence homology and cause silencing [34], or have other deleterious effects, such as chromatin silencing [30].

Some studies suggest that expanded repeat RNAs form hairpin-like structures similar to dsRNA that becomes cleaved into small RNA. This raises the idea that expansion of the repeat in a single transcript could confer gain-of-function effects through the generation of small RNAs that may target the expression of other genes (Figure 2). For example, cell culture studies suggest that expanded repeats with the sequence of CNG (N=A, U, or G) can be recognized by the ribonuclease Dicer (albeit inefficiently) and processed into 21 nucleotide small RNAs [33, 34]. Such small RNAs could trigger downstream gene silencing effects. The breadth and role of such interactions in pathological symptoms will be interesting to define.

Signaling pathways

Expanded CUG repeat RNA has also been found to induce cell signaling through activation of protein kinase C (PKC) [6]. Since PKC has a variety of substrates and plays a broad role in many aspects of cellular metabolism such as cell death and differentiation, abnormal activation could confer gain-of-function properties to proteins and affect a range of cellular functions. In DM1, activation of PKC is shown to cause hyperphosphorylation of CUGBP1, whose increase contributes to the muscle and heart symptoms [6]. Expanded repeats have also been suggested to activate other signaling pathways such as PKR (ds-RNA-activated protein kinase) [35]. A fascinating question is the molecular mechanism by which the expanded repeat RNA triggers these signaling pathways, and whether this or other signaling pathways could be activated by expanded repeat regions and contribute to other RNA-mediated diseases.

EFFECTS OF THE NUCLEOTIDE REPEATS ON EXPRESSION OF THE DISEASE GENE ITSELF

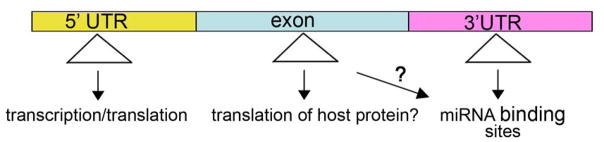

Beyond dominant effects of the pathogenically expanded repeat RNA on the function of other cellular factors, the repeat expansion may also regulate the expression of the gene in which it is located. Depending on the location and the type of sequence, repeat expansion can have different effects on gene expression (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The expanded repeat may regulate the expression of the host gene. Expansions within the 5′ UTR may affect transcription, translation, and stability of the mRNA. Expansions within the open reading frame not only affect function of the protein, but may also affect the translation of the protein. Repeat expansions within the 3′UTR may affect the expression of a gene, RNA stability, translation or regulation, such as affecting protein translation through miRNA binding sites, or causing frameshifting.

Effects on untranslated regions

Since the 3′ or 5′ UTR of an mRNA typically contains regulatory elements that modulate gene expression, repeat expansion may affect these elements, thereby altering gene expression. For example, the moderate expansions of the CGG repeat (60–200) in the 5′UTR of FMR1 gene which underlie FXTAS, leads to accumulation of the mRNA in disease, although is suggested to decrease translation efficiency of FMR protein in vitro [36]. Since FMRP is an RNA-binding protein critical for local mRNA translation at synapses [37], this raises the possibility that altered translation of FMRP may contribute to FXTAS symptoms. Longer CGG repeats (>200) cause increased methylation in the 5′ regulatory region of the FMR1 gene, leading to loss of FMR1 expression and the symptoms of fragile X [37]. Thus, FXTAS is a late-onset disorder due to toxicity of moderate CGG repeat expansions, whereas longer expansions cause developmental fragile X.

miRNA pathways have also been implicated in neurodegenerative disease from findings that reducing miRNA pathway activity enhances degeneration induced by specific disease proteins [38]. Compromise of the miRNA pathway can also cause degeneration on its own [39]. Repeat expansions in the RNA may additionally affect accessibility of miRNA binding sites in the 3′UTR, thereby altering disease gene expression. Recently the human Aaxin-1 gene, in which an expanded CAG repeat in the coding sequence causes SCA1, has been found to be regulated by several miRNAs [40]. Loss of miRNA activity could lead to increased expression of the Ataxin-1 protein, resulting in disease symptoms. It is of interest to address whether and how expansion of the CAG repeat may affect miRNA binding. Similarly, Drosophila Atrophin-1, an ortholog of human Atrophin-1 which is implicated in the polyQ disease DPRLA, is regulated by miR-8 [41]. In Drosophila, loss of miR-8 results in accumulation of the fly Atrophin-1 protein and neurotoxic effects. These results highlight that altered RNA or miRNA levels — in these examples, loss of miRNA activity—can have a dramatic effect on the level of disease proteins in a manner that can contribute to disease symptoms.

Effects of protein-coding repeats

Since expansion of repeats located within the protein-coding region results in an abnormally long amino acid tract, much attention has been placed on potential abnormal interactions of the consequent protein. For example, in polyQ diseases, an expanded polyQ tract caused by the CAG repeat expansion may confer toxic gain-of-function activities on the host protein. The expanded polyQ tract could also alter the conformation of the host protein, thereby inducing loss-of-function effects by disrupting normal protein functions [1].

Since the expanded repeat sequence can also alter the conformation of the mRNA, it seems reasonable to propose that an expanded repeat tract within the protein-coding region may affect the translation of the host protein. Consistent with this hypothesis, studies in Drosophila suggest that interruptions of a continuous CAG repeat with CAA in Ataxin-3 disease gene increase the ratio of the protein to the RNA, compared to the Ataxin-3 protein encoded by a pure CAG repeat RNA [18]. Therefore protein-encoding repeat expansions with different sequences could affect the translation efficiency of the protein. Along this line, it has been noted that CAG repeat expansions in the Ataxin-2 gene typically present with ataxia in spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (SCA2) disease, whereas similar length repeats that are interrupted with CAA codons can present with parkinsonism symptoms[42]. A number of mechanisms may underlie this differential disease manifestation, such as different rates of instability of the CAG repeat mRNA or distinct interactions with select RNA-binding proteins. It is also possible that interruptions of the CAG repeat could affect protein translation, thereby affecting Ataxin-2 protein levels and thus activity. Some models suggest that long CAG repeats can lead to stuttering of ribosomes and/or frame-shifts, causing decreased translation efficiency or altered amino acid sequence of the protein [43]. Such mechanisms raise additional complexities for these diseases.

FUTURE STUDIES

The studies highlighted indicate that the approach of defining proteins that bind the abnormally expanded repeat RNA has been particularly fruitful, yielding a number of different RNA-binding proteins that interact with repeats in either a specific or general manner. While the initial findings in DM1 have focused on alterations in splicing, studies now suggest a number of cellular pathways could be disrupted by RNA toxicity. What other functions and RNA processing pathways are affected, and what are their specific contributions to each disease? Further studies regarding these questions will be critical for developing effective treatments (Box 2).

BOX 2. Future topics of interest.

The scope of trinucleotide repeat RNAs toxicity

While initial findings focused on the pathogenic effects of expanded repeat RNA on splicing, recent studies suggest that a number of cellular pathways may be disrupted by RNA toxicity, such as sense/anti-sense transcripts and interactions, cell signaling, protein quality control, and protein translation machinery. To further understand how these cellular pathways could be affected by a specific type of repeat RNA will be critical for mechanistic insight into each disease and developing therapeutic approaches.

Multi-layer disease symptoms

One principle being revealed is that there may be multiple components to any one disease, including dominant effects at the level of the repeat RNA, abnormal protein interactions due to loss- and gain-of-function interactions, and sense/anti-sense transcript interactions. Thus therapeutics may require multiple approaches targeting different aspects of the pathological processes for any one situation.

Shared components in seemingly different disease situations

Findings to date suggest that many repeat expansion diseases may have toxic contributions conferred by both the abnormal protein and the RNA. For example, ubiquitinated inclusions and modulation by chaperones may occur in both RNA-based and protein-based repeat expansion diseases. Since such features also characterize other neurodegenerative situations such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases, seemingly different diseases may share pathogenic processes. Therapeutic approaches that target common elements may be an appealing approach, such that a treatment for one may have potential to be a treatment for many situations.

An additional principle being revealed is that there may be multiple components to a disease situation, and shared components in seemingly different disease situations (Box 2). Repeat expansion diseases may be composed of both toxic contributions of the abnormal protein as well as the RNA, and ubiquitinated inclusions and modulation by chaperones may occur in both RNA-based and protein-based toxic situations. What do these shared features mean with respect to precise mechanisms, and importantly, possible shared therapeutic approaches? Ultimately, as multiple levels of toxicities may be involved in one disease, including both RNA, protein, anti-sense and sense/anti-sense transcript interactions, effective therapeutic treatment may need to involve multiple approaches targeting different processes.

The breath and the scope of RNA functions in cellular metabolism have exploded, with arguably RNA, rather than protein, comprising the major contribution of the genome to biological function. Many types of RNA sequences, including small RNAs and long non-coding RNAs, are found to play important regulatory roles. Expansion of nucleotide repeat motifs is one specific sequence that underlies a number of neurological and neurodegenerative diseases. As the number of situations grows in which the RNA is shown to contribute toxic components, understanding the pathological mechanisms by which such RNAs induce neuronal dysfunction will be critical to developing effective treatment for these diseases. The hope is that such study may also provide insights into fundamental pathways that regulate neuronal activity and long term neuronal maintenance.

Acknowledgments

We thank Zhenming Yu, Nan Liu, and Vivian Ericson for comments. LBL is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Federation for Aging Research (AFAR), in the laboratory of Dr. Kang Shen. NMB is supported by funding from the NINDS, the NIGMS and the Ellison Medical Foundation. NMB is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References

- 1.Orr HT, Zoghbi HY. Trinucleotide repeat disorders. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:575–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ranum LP, Cooper TA. RNA-mediated neuromuscular disorders. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:259–277. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wheeler TM, Thornton CA. Myotonic dystrophy: RNA-mediated muscle disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2007;20:572–576. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3282ef6064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ho TH, et al. Muscleblind proteins regulate alternative splicing. Embo J. 2004;23:3103–3112. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Savkur RS, et al. Aberrant regulation of insulin receptor alternative splicing is associated with insulin resistance in myotonic dystrophy. Nat Genet. 2001;29:40–47. doi: 10.1038/ng704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuyumcu-Martinez NM, et al. Increased steady-state levels of CUGBP1 in myotonic dystrophy 1 are due to PKC-mediated hyperphosphorylation. Mol Cell. 2007;28:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mankodi A, et al. Myotonic dystrophy in transgenic mice expressing an expanded CUG repeat. Science. 2000;289:1769–1773. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5485.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orengo JP, et al. Expanded CTG repeats within the DMPK 3′ UTR causes severe skeletal muscle wasting in an inducible mouse model for myotonic dystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2646–2651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708519105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho TH, et al. Transgenic mice expressing CUG-BP1 reproduce splicing mis-regulation observed in myotonic dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1539–1547. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanadia RN, et al. A muscleblind knockout model for myotonic dystrophy. Science. 2003;302:1978–1980. doi: 10.1126/science.1088583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanadia RN, et al. Reversal of RNA missplicing and myotonia after muscleblind overexpression in a mouse poly(CUG) model for myotonic dystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11748–11753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604970103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wheeler TM, et al. Reversal of RNA dominance by displacement of protein sequestered on triplet repeat RNA. Science. 2009;325:336–339. doi: 10.1126/science.1173110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mulders SA, et al. Triplet-repeat oligonucleotide-mediated reversal of RNA toxicity in myotonic dystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13915–13920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905780106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warf MB, et al. Pentamidine reverses the splicing defects associated with myotonic dystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18551–18556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903234106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daughters RS, et al. RNA gain-of-function in spinocerebellar ataxia type 8. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000600. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang H, et al. Myotonic dystrophy type 1 is associated with nuclear foci of mutant RNA, sequestration of muscleblind proteins and deregulated alternative splicing in neurons. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:3079–3088. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yuan Y, et al. Muscleblind-like 1 interacts with RNA hairpins in splicing target and pathogenic RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:5474–5486. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li LB, et al. RNA toxicity is a component of ataxin-3 degeneration in Drosophila. Nature. 2008;453:1107–1111. doi: 10.1038/nature06909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iwahashi CK, et al. Protein composition of the intranuclear inclusions of FXTAS. Brain. 2006;129:256–271. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Onishi H, et al. MBNL1 associates with YB-1 in cytoplasmic stress granules. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:1994–2002. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sofola OA, et al. RNA-binding proteins hnRNP A2/B1 and CUGBP1 suppress fragile X CGG premutation repeat-induced neurodegeneration in a Drosophila model of FXTAS. Neuron. 2007;55:565–571. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin P, et al. Pur alpha binds to rCGG repeats and modulates repeat-mediated neurodegeneration in a Drosophila model of fragile X tremor/ataxia syndrome. Neuron. 2007;55:556–564. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khalili K, et al. Puralpha is essential for postnatal brain development and developmentally coupled cellular proliferation as revealed by genetic inactivation in the mouse. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:6857–6875. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.19.6857-6875.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tai HC, Schuman EM. Ubiquitin, the proteasome and protein degradation in neuronal function and dysfunction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:826–838. doi: 10.1038/nrn2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin P, et al. RNA-mediated neurodegeneration caused by the fragile X premutation rCGG repeats in Drosophila. Neuron. 2003;39:739–747. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00533-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Auluck PK, Bonini NM. Pharmacological prevention of Parkinson disease in Drosophila. Nat Med. 2002;8:1185–1186. doi: 10.1038/nm1102-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warrick JM, et al. Suppression of polyglutamine-mediated neurodegeneration in Drosophila by the molecular chaperone HSP70. Nat Genet. 1999;23:425–428. doi: 10.1038/70532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katayama S, et al. Antisense transcription in the mammalian transcriptome. Science. 2005;309:1564–1566. doi: 10.1126/science.1112009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yelin R, et al. Widespread occurrence of antisense transcription in the human genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:379–386. doi: 10.1038/nbt808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cho DH, et al. Antisense transcription and heterochromatin at the DM1 CTG repeats are constrained by CTCF. Mol Cell. 2005;20:483–489. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moseley ML, et al. Bidirectional expression of CUG and CAG expansion transcripts and intranuclear polyglutamine inclusions in spinocerebellar ataxia type 8. Nat Genet. 2006;38:758–769. doi: 10.1038/ng1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ladd PD, et al. An antisense transcript spanning the CGG repeat region of FMR1 is upregulated in premutation carriers but silenced in full mutation individuals. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:3174–3187. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Handa V, et al. The fragile X syndrome repeats form RNA hairpins that do not activate the interferon-inducible protein kinase, PKR, but are cut by Dicer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:6243–6248. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krol J, et al. Ribonuclease dicer cleaves triplet repeat hairpins into shorter repeats that silence specific targets. Mol Cell. 2007;25:575–586. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tian B, et al. Expanded CUG repeat RNAs form hairpins that activate the double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase PKR. RNA. 2000;6:79–87. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200991544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ofer N, et al. The quadruplex r(CGG)n destabilizing cationic porphyrin TMPyP4 cooperates with hnRNPs to increase the translation efficiency of fragile X premutation mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:2712–2722. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bassell GJ, Warren ST. Fragile X syndrome: loss of local mRNA regulation alters synaptic development and function. Neuron. 2008;60:201–214. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bilen J, et al. A new role for microRNA pathways: modulation of degeneration induced by pathogenic human disease proteins. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2835–2838. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.24.3579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schaefer A, et al. Cerebellar neurodegeneration in the absence of microRNAs. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1553–1558. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee Y, et al. miR-19, miR-101 and miR-130 co-regulate ATXN1 levels to potentially modulate SCA1 pathogenesis. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1137–1139. doi: 10.1038/nn.2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karres JS, et al. The conserved microRNA miR-8 tunes atrophin levels to prevent neurodegeneration in Drosophila. Cell. 2007;131:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Furtado S, et al. Profile of families with parkinsonism-predominant spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (SCA2) Mov Disord. 2004;19:622–629. doi: 10.1002/mds.20074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wills NM, Atkins JF. The potential role of ribosomal frameshifting in generating aberrant proteins implicated in neurodegenerative diseases. Rna. 2006;12:1149–1153. doi: 10.1261/rna.84406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brook JD, et al. Molecular basis of myotonic dystrophy: expansion of a trinucleotide (CTG) repeat at the 3′ end of a transcript encoding a protein kinase family member. Cell. 1992;68:799–808. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fu YH, et al. An unstable triplet repeat in a gene related to myotonic muscular dystrophy. Science. 1992;255:1256–1258. doi: 10.1126/science.1546326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mahadevan M, et al. Myotonic dystrophy mutation: an unstable CTG repeat in the 3′ untranslated region of the gene. Science. 1992;255:1253–1255. doi: 10.1126/science.1546325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liquori CL, et al. Myotonic dystrophy type 2 caused by a CCTG expansion in intron 1 of ZNF9. Science. 2001;293:864–867. doi: 10.1126/science.1062125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thornton CA, et al. Myotonic dystrophy with no trinucleotide repeat expansion. Ann Neurol. 1994;35:269–272. doi: 10.1002/ana.410350305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hagerman RJ, et al. Intention tremor, parkinsonism, and generalized brain atrophy in male carriers of fragile X. Neurology. 2001;57:127–130. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kawaguchi Y, et al. CAG expansions in a novel gene for Machado-Joseph disease at chromosome 14q32.1. Nat Genet. 1994;8:221–228. doi: 10.1038/ng1194-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Day JW, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 8: clinical features in a large family. Neurology. 2000;55:649–657. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.5.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koob MD, et al. An untranslated CTG expansion causes a novel form of spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA8) Nat Genet. 1999;21:379–384. doi: 10.1038/7710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.O’Hearn E, et al. SCA-12: Tremor with cerebellar and cortical atrophy is associated with a CAG repeat expansion. Neurology. 2001;56:299–303. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Holmes SE, et al. A repeat expansion in the gene encoding junctophilin-3 is associated with Huntington disease-like 2. Nat Genet. 2001;29:377–378. doi: 10.1038/ng760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Timchenko LT, et al. Identification of a (CUG)n triplet repeat RNA-binding protein and its expression in myotonic dystrophy. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4407–4414. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.22.4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]