Abstract

Background

Large portosystemic shunts (PSSs) may lead to recurrent encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis and embolization of these shunts may improve encephalopathy.

Material and methods

Five patients underwent balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) or plug-assisted retrograde transvenous obliteration (PARTO) of a large PSS at our center in last 2 years for recurrent hepatic encephalopathy (HE) at a tertiary care center at north India. Data are shown as number and mean ± SD. None of these patients had Child's C cirrhosis or presence of large ascites/large varices.

Results

Five patients (all males), aged 61 ± 7 years, underwent BRTO or PARTO for recurrent HE and presence of lienorenal (n = 4) or mesocaval shunt (n = 1). The etiology of cirrhosis was cryptogenic/non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in 3, and alcohol and hepatitis B in one each. All patients had Child's B cirrhosis; Child's score was 8.6 ± 0.5, model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score was 13.4 ± 2.3. One patient had mild ascites; 3 patients had small esophageal varices before procedure. Sclerosants (combination of air, sodium tetradecyl sulphate, and lipiodol) were used in two patients, endovascular occlusion plugs were used in two patients, and both sclerosants and endovascular occlusion plug were used in one patient. Embolization of minor outflow veins to allow for stable deposition sclerosants in dominant shunt was done using embolization coils and glue in two patients. One patient needed 2 sessions. The pre-procedure ammonia was 127 ± 35 which decreased to 31 ± 17 after the shunt embolization. There was no recurrence of encephalopathy in any of these patients. One patient was lost to follow-up at 6 months; others are doing well at 6 months (n = 2), 10 months (n = 1) and 2 years (n = 1). None of these patients developed further decompensation in the defined follow-up period.

Conclusion

Good results can be obtained in selected patients after embolization of large PSS for recurrent HE.

Abbreviations: BRTO, balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration; CTP, Child–Turcotte–Pugh; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; PARTO, plug-assisted retrograde transvenous obliteration; PSSs, portosystemic shunts

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a difficult problem in patients with cirrhosis that requires hospitalization. Recurrent HE is associated with increased risks of mortality. Both liver dysfunction (severity of liver disease) and portosystemic shunting contribute to pathogenesis of HE. Some of the patients with early-stage cirrhosis experience recurrent encephalopathy without precipitating event which is difficult to manage on medical therapies.1, 2, 3 Presence of large portosystemic shunts (PSSs) may lead to recurrent/persistent encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis and embolization of these shunts may improve encephalopathy. Results of shunt embolization have been shown to be good in patients with low model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) or Child's score and patients with advanced decompensation may not benefit and ascites/variceal status may worsen in these patients.4, 5 We describe our experience of embolization of a large PSS in five patients.

Material and Methods

The study was conducted at a tertiary care center in North India. Patients with cirrhosis and recurrent HE who underwent balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) or plug-assisted retrograde transvenous obliteration (PARTO) for large PSS (size subjective on imaging in presence of recurrent HE) embolization were analyzed retrospectively. Patients were counseled about various treatment options including liver transplantation as and when applicable. BRTO or PARTO were done by interventional radiology team. A total of 6 BRTO or PARTO (Table 1) procedures were done in 5 patients. Venous access was achieved using right femoral vein (n = 4) and right internal jugular vein (n = 2) in six procedures. Four patients required single treatment session and one patient required two treatment sessions (within same admission), and second time venous access was taken from right internal jugular vein. Sclerosants (combination of air, sodium tetradecyl sulfate, and lipiodol) were used in two patients, endovascular occlusion plugs (Amplatzer vascular plug) were used in two patients, and both sclerosants and endovascular occlusion plug were used in one patient. Embolization of minor outflow veins was done using embolization coils and glue in two patients, to allow for stable deposition sclerosants in dominant shunt. All these patients were inpatients at the time of procedure.

Table 1.

Details of 5 Patients.

| S. no. | Age, sex | Etiology | Type of shunt | Procedure done with | Baseline bilirubin, INR | CTP/MELD | Follow up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 63 M | NASH | lienorenal | Sclerosant | 3, 1.1 | 9/14 | 3 months |

| 2 | 73 M | Cryptogenic | Lienorenal | Vascular plugs | 1.4, 1.29 | 8/11 | 10 months |

| 3 | 60 M | Cryptogenic | Mesocaval | Vascular plugs, needed 2 sessions | 1.9, 1.29 | 9/15 | 6 months |

| 4 | 60 M | Ethanol | Lienorenal | Sclerosant | 1, 1.3 | 8/11 | 6 months |

| 5 | 52 M | Hepatitis B | Lienorenal | Sclerosant + vascular plugs | 3, 1.23 | 9/16 | 2 years |

Results

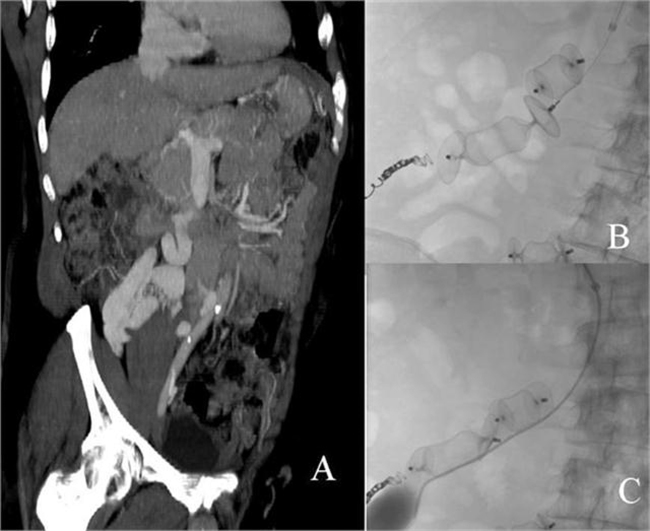

Five patients (all males), aged 61 ± 7 years underwent BRTO or PARTO for recurrent HE and presence of large lienorenal (n = 4) or mesocaval shunt (n = 1) at our center in last 2 years for recurrent HE. The etiology of cirrhosis was cryptogenic/non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in 3, and alcohol and hepatitis B in one each. All patients had Child's B cirrhosis; Child's score was 8.6 ± 0.5 and MELD score was 13.4 ± 2.3. Details of these patients are shown in Table 1. Four patients required single treatment session and one patient (number 3) required two treatment sessions (within same admission) and venous access was obtained from right internal jugular vein during second time. Representative images of 2 patients are shown as Figure 1, Figure 2. The patient number 3 had two shunts, superior mesenteric vein to left common iliac vein and to inferior vena cava; both of these were occluded with vascular plugs and a coil was placed in a small collateral related to shunt draining into inferior vena cava. As shown in Figure 3, Case 1 had fever post-procedure; cultures were sterile and he improved on antibiotics. Ammonia levels pre- and post-procedure were available for 4 patients; the pre-procedure ammonia was 127 ± 35 μmol/l, which decreased to 31 ± 17 after procedure.

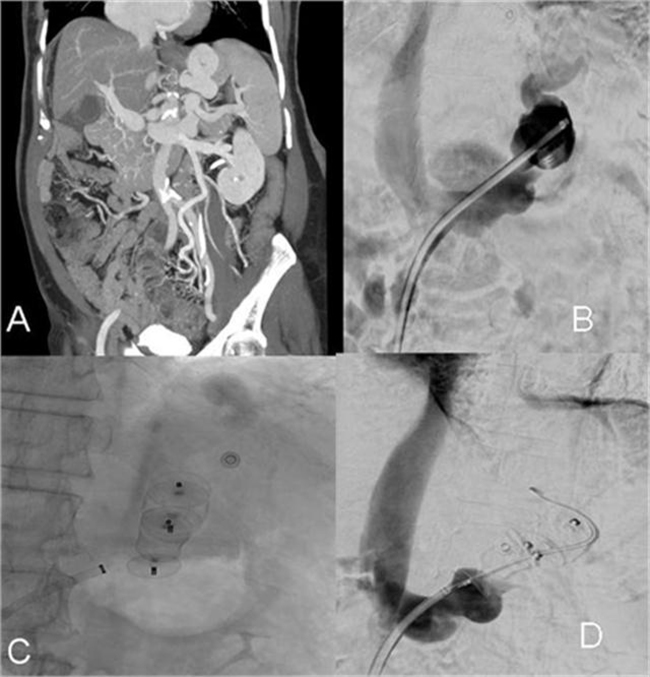

Figure 1.

(A) Coronal CT portal venogram shows leinorenal shunt; (B) catheter renal venogram shows leinorenal shunt; (C) embolization of leinorenal shunt by vascular embolizing plugs; (D) no flow in the leinorenal shunt after embolization.

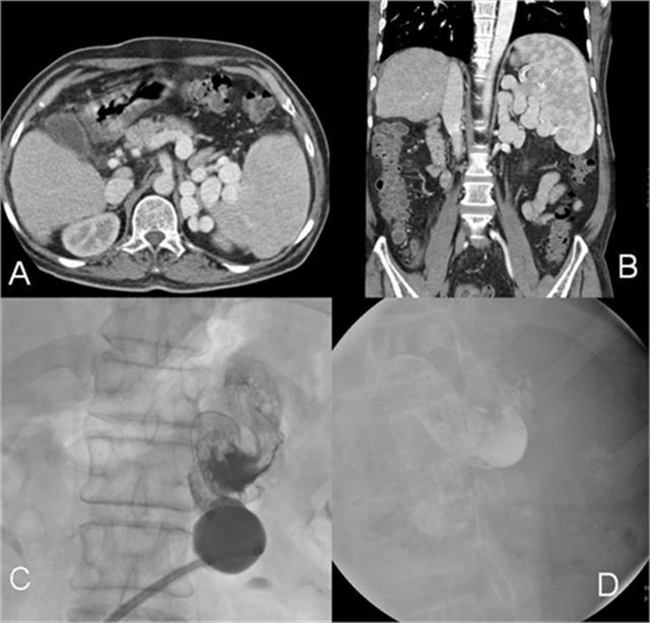

Figure 2.

(A and B) Axial and coronal images of CT portal venography showing large leinorenal collaterals; (C) balloon inflation with sclerosant in leinorenal shunt; (D) stable sclerosant cast in leinorenal shunt after balloon deflation.

Figure 3.

(A) Presence of mesocaval shunt; (B) vascular plugs in mesocaval shunt, a coil (in a small collateral related to mesocaval shunt) and a vascular plug (in shunt draining to left common iliac) also visible in lower part of image; (C) no flow in mesocaval shunt after plug-assisted obliteration.

Follow-up: four patients are free of HE and are alive at a follow-up of 3, 6, 10 and 24 months. One patient was lost to follow-up after 6 months of HE-free period. Case 4 had mild ascites before procedure; there was no worsening or new development of ascites in any of these patients. Three of these patients had small esophageal varices before shunt occlusion procedure; follow-up endoscopy was done after 6 months in 1 patient which showed same degree of esophageal varices.

Discussion

HE is a common problem in patients with cirrhosis and recurrent HE is associated with increased risks of patient death and need of frequent hospitalization. HE in patients with cirrhosis generally occurs due to combination of hepatocellular dysfunction and portosystemic shunting; hence, it is more common in patients with advanced state of cirrhosis. However, some patients with early-stage cirrhosis still experience recurrent episodes of encephalopathy without an obvious precipitating event or significant liver dysfunction and they may be refractory to standard medical therapies.1, 2, 3 Recurrent HE which is difficult to manage is a difficult situation for both doctors and patients. It requires repeated admissions and is a cause of significant morbidity if liver transplantation cannot be offered for some reason. Some of these patients have recurrent HE due to large PSSs which are possible therapeutic targets. Riggio et al.6 compared 14 patients with cirrhosis and recurrent or persistent HE to 14 age and degree of liver failure controls (cirrhosis without HE). Large spontaneous PSSs were detected in 10 (71%) patients with HE and in 2 (14%) patients without HE (P = 0.002). The patients with HE had significantly lower chances of having ascites or medium/large esophageal varices.6, 7 Several studies have shown improvement of HE after embolization of these shunts.4, 5, 8 BRTO has been described in patients with PSSs and recurrent encephalopathy. Mukund et al. described seven patients in whom BRTO was done for portosystemic collaterals leading to recurrent encephalopathy. The authors reported 86% technical success; one patient needed second session of BRTO. The authors encountered complications related to procedure in 2 patients. The clinical improvement was seen up to 3 months (study period).4 An et al.5 compared 17 patients with shunt block for recurrent HE with 17 controls. The authors found a significantly lower HE recurrence rate of 39.9% in embolization group as compared to controls (79.9%, P = 0.02); however, there was no difference in 2-year survival; MELD and Child–Turcotte–Pugh (CTP) score were significant predictors of 2-year patient mortality in the embolization group. The patients with MELD < 15 in the absence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) showed that 2-year overall survival rate was significantly higher in the embolization group than in the control group (100% vs. 60%, P = 0.03).5 Lyn et al. described experience of large PSS obliteration in 20 (13 with persistent and 7 with recurrent HE) patients. The authors studied improvement in immediate (7 days), intermediate (1–4 months), and long-term (6–12 months) time frames. The authors found immediate (20/20) and intermediate (18/18) improvement in all and 92% (11/12) in long term. Ten percent had procedural related complications (all resolved) and six developed new or worsening ascites.8 In data from European multicentric working group over 14 years, the authors described that 37 patients with refractory HE were diagnosed as having single large spontaneous portosystemic shunts (SPSSs).9 After shunt embolization, 59.4% were free of HE and 48.6% of patients remained HE-free over a mean follow-up period of 697 ± 157 days. The authors also noted improved autonomy and decreased frequency of hospitalizations/severity of the worst HE episode after embolization in 75% of these patients. The severity of liver disease as defined by MELD score was the strongest positive predictive factor of HE recurrence with a cutoff of 11 for patient selection in regression analysis. The impact of shunt embolization on future course of liver disease is variable. While Ann et al. showed increased survival in selected patients,5 Laleman et al. showed de novo development of small esophageal varices in 2 and ascites in 6 patients.9 Embolization of large SPSS in patients with cirrhosis and residual hepatic functional reserve may help restore portal flow, improving liver function and reducing brain exposure to neurotoxic substances (thus improvement of HE).5, 10 None of the patients in current series experienced HE after embolization; however, it should be noted that all patients were carefully selected and none of these patients had advanced liver disease as shown in Table 1.

In conclusion, we present 5 cases with recurrent HE with a single large PSS who responded to shunt embolization. While shunt embolization may improve recurrent HE in such patients, patients with lower degrees of liver dysfunction are mainly benefited and this process may increase portal hypertension and related complications.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have none to declare.

Acknowledgement

Mr. Yogesh Saini (research coordinator).

References

- 1.Poordad F.F. Review article: the burden of hepatic encephalopathy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(suppl 1):3–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-6342.2006.03215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ustamante J., Rimola A., Ventura P.J. Prognostic significance of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 1999;30:890–895. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80144-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crespin J., Nemcek A., Rehkemper G., Blei A.T. Intrahepatic portal-hepatic venous anastomosis: a portal-systemic shunt with neurological repercussions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1568–1571. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mukund A., Rajesh S., Arora A., Patidar Y., Jain D., Sarin S.K. Efficacy of balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration of large spontaneous lienorenal shunt in patients with severe recurrent hepatic encephalopathy with foam sclerotherapy: initial experience. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23:1200–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.An J., Kim K.W., Han S., Lee J., Lim Y.S. Improvement in survival associated with embolization of spontaneous portosystemic shunt in patients with recurrent hepatic encephalopathy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:1418–1426. doi: 10.1111/apt.12771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riggio O., Efrati C., Catalano C. High prevalence of spontaneous portal-systemic shunts in persistent hepatic encephalopathy: a case–control study. Hepatology. 2005;42:1158–1165. doi: 10.1002/hep.20905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohnishi K., Sato S., Saito M. Clinical and portal hemodynamic features in cirrhotic patients having a large spontaneous splenorenal and/or gastrorenal shunt. Am J Gastroenterol. 1986;81:450–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyn A.M., Singh S., Congly S.E. Embolization of portosystemic shunts for treatment of medically refractory hepatic encephalopathy. Liver Transpl. 2016;22:723–731. doi: 10.1002/lt.24440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laleman W., Simon-Talero M., Maleux G. Embolization of large spontaneous portosystemic shunts for refractory hepatic encephalopathy: a multicenter survey on safety and efficacy. Hepatology. 2013;57:2448–2457. doi: 10.1002/hep.26314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiao L.R., Seifalian A.M., Mathie R.T., Habib N., Davidson B.R. Portal flow augmentation for liver cirrhosis. Br J Surg. 2000;87:984–991. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]