Abstract

This study aimed to explore the extent to which self-conscious emotions are expressed, to explore any associations with adverse health outcomes, and to compare self-conscious emotions in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) to healthy controls. A two-stage mixed-methods study design was employed. Interviews with 15 individuals with COPD informed the choice of questionnaires to assess self-conscious emotions which were completed by individuals with COPD and healthy controls. Five overarching themes were abstracted: grief, spectrum of blame, concern about the view of others, concealment, and worry about the future. The questionnaires were completed by 70 patients (mean(SD) age 70.8(9.4) years, forced expiratory volume in one second predicted 40.5(18.8), 44% male) and 61 healthy controls (mean(SD) age 62.2(12.9) years, 34% male]. Self-conscious emotions were associated with reduced mastery, heightened emotions, and elevated anxiety and depression (all p < 0.001). Individuals with COPD reported lower self-compassion, higher shame, and less pride than healthy controls (all p ≤ 0.01). There is a need to increase awareness of self-conscious emotions in individuals with COPD. Therapies to target such emotions may improve mastery, emotions, and psychological symptoms.

Keywords: Mixed-methods, COPD, shame, guilt, compassion

Introduction

Symptoms of breathlessness on exertion limit the ability of individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) to sustain physical and social activities which are important for well-being, compromising quality of life and leading to psychological co-morbidities.1–3 Personal culpability for COPD is often experienced due to the onset of the disease being commonly attributed to smoking behavior, potentially leading to self-conscious emotions.

Self-conscious emotions related to our experience of self which is shaped by fluctuating emotions and feelings such as guilt, shame, pride, embarrassment, and self-blame, which could not exist without perceptions and evaluations of the self 4 (supplement 1). In individuals with COPD such feelings of self-worth may be compromised by the presence of a chronic, debilitating disease, which requires seeking help from family members.5 Visible differences conferred by symptoms as well as dependency on others and on devices may force patients to reappraise their identity within the context of their disease.6

Constructions of self-blame and personal culpability for disease are prominent in narratives of patients with COPD.7–9 This is perhaps unsurprising if communicated by the substantial proportion of physicians who believe that patients with COPD are to blame for their disease.10 The experience of self-blame and concern about the manner in which others view their behavior has been associated with negative emotional responses including feeling shamed, disgraced, depressed, and embarrassed, leading to reduced help-seeking, reduced adherence to oxygen therapy, failure to attend pulmonary rehabilitation (PR), and social isolation.7,11–13

To date, such issues have been elicited from patients’ narratives describing their disease experience or exploring views on smoking behavior.7,9 We chose to adopt a mixed-methods approach consisting of qualitative and quantitative methodologies to explore the extent to which self-conscious emotions are expressed in patients with COPD, to explore any associations with reduced health-related quality of life (HRQOL), self-efficacy, or increased psychological symptoms and to compare self-conscious emotions in individuals with COPD to healthy controls.

Methods

Study design

A two-stage mixed-methods study design was employed. Qualitative techniques enable the collection of detailed data allowing for true meaning and contradictions to be explored. Information arising from the qualitative phase informed the choice of questionnaires to assess self-conscious emotions which are relevant to individuals with COPD. These questionnaires will be utilised alongside measures of HRQOL, mood, and self-efficacy, commonly examined in individuals with COPD.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the The Joint Bridgepoint Health – West Park Healthcare Centre – Toronto Central Community Care Access Centre – Toronto Grace Health Centre Research Ethics Board and all participants provided written informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

Recruitment

Individuals with COPD

Eligible patients had a diagnosis of COPD confirmed by spirometry, a smoking history greater than 10 pack years, resided in the community, and were able to provide written informed consent. Individuals were excluded if they had a primary respiratory diagnosis other than COPD and an inability to communicate because of language skills, hearing, or cognitive impairment. Consecutive patients with COPD were approached in an outpatient respiratory clinic held at a specialized rehabilitation center.

Healthy controls

Multiple strategies were used for the recruitment of healthy controls who volunteered to participate. Friends and family members of patients who attended respiratory clinics were told about the study. Posters, emails, advertisements, and announcements were displayed at the rehabilitation center.

To be considered eligible controls had to consider themselves “healthy” and be over 40 years old. Subjects were excluded if they had a chronic respiratory condition.

Data collection

Phase 1: Qualitative phase

A semi-structured interview schedule consisting of open-ended questions was informed by the results of a previous study exploring the views of patients who refused a referral to PR following an acute exacerbation (Supplement 2).13 Feedback was provided from a patient advisory group consisting of four members. The interview schedule was revised throughout data collection to improve the clarity of the questions.

SH interviewed participants individually in a quiet room at the health care center. Interviews lasted between 20 min and 60 min and were largely patient-led.

Phase 2: Quantitative phase

Patients completed a questionnaire pack consisting of self-reported measures of self-conscious emotions, COPD-specific items of self-consciousness, HRQOL, self-efficacy, and psychological symptoms. Informed by the qualitative findings, the researchers (SH and DB) initially selected four measures which were presented to members of a collaborative workshop consisting of a research assistant, a nurse, an occupational therapist, a physiotherapist, two respirologists, two scientists, one PhD student, and one clinical care coordinator. Following discussion, one measure was dispensed with, one was replaced, and two were considered appropriate. The three proposed measures were presented to a patient advisory group consisting of four individuals with COPD who approved their use.

The COPD-specific items of self-consciousness were developed initially by the researchers (SH and DB) and were informed by the qualitative findings. The issue of blame is covered by question 1, concern about the view of others on visible symptoms, i.e. coughing is explored via question 2, concealment including hiding the disease, not wishing to be a burden, seeking compassion and understanding from others, and self-worth is represented by questions 3, 4, 8, 9, and 10, worry State about the immediate and long-term future is covered in questions 5 and 6 and question 7 tackles feelings of grief. The items were piloted on members of the PAG group who agreed the content and format.

Healthy controls completed a questionnaire pack consisting of the three measures of self-consciousness only.

The Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale

The Brief Fear Negative Evaluation (BFNE) scale is a valid and reliable measure of social anxiety (α = 0.97).14,15 It is convenient for use consisting of 12 items measured on a five-point Likert scale (one to five). Scores range from 12 to 60 with higher scores indicating greater apprehension about others evaluations.

The Shame and Guilt Scale

The State Shame and Guilt Scale (SGS) contains five shame items (α = 0.89), five guilt items (α = 0.82), and five pride items (α = 0.78).16 Responses are given on a five-point Likert scale (1 = always feeling this way to 5 = never feeling this way). Lower scores indicate increased feelings of shame and guilt and elevated levels of pride. The scale was adapted to ask how individuals had felt “in the past 2 weeks” rather than at the present moment to counteract any influence of the hospital setting on levels of shame or guilt.

The self-compassion scale-short form

The Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form (SCS-SF) assesses six aspects of self-compassion: self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification.17 The 12 items are rated on a five-point response scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). The shortened scale correlates well with the full SCS when reporting total score (r ≥ 0.97) but is less reliable for each domain.18 The total score is calculated by adding together each item and dividing by 12.

COPD-specific items of self-consciousness

Ten items are included and each item is scored on a five-point Likert scale. Positive and negative statements were included to mitigate perception of researchers’ judgment.

Health-related quality of life – The Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire-Self Reported

The Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire-Self Reported (CRQ-SR) is a self-reported measure of health status shown to be valid and reliable in patients with COPD.19, 20 It consists of four dimensions: dyspnoea, fatigue, emotion, and mastery. Mean score is calculated per dimension providing a range between 1 and 7, a higher score indicates better health status.

Self-efficacy – The pulmonary rehabilitation adapted index of self-efficacy

The pulmonary rehabilitation adapted index of self-efficacy (PRAISE) has been fully validated in a PR population.21 The tool consists of 15 questions, each one scored from 1 to 4 with 4 being the highest level of perceived self-efficacy.

Psychological symptoms - The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) comprises of two subscales: anxiety (α = 0.68) and depression (α = 0.91) with a score range of 0 to 21. Scores ≥11 for each sub-scale are considered to indicate clinical caseness.22

Data analysis

Phase 1: Qualitative phase

All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The data was stored and organized using a computer software program (QSR NVivo version 9; QSR International, Doncaster, Australia) and analyzed using inductive thematic analysis.

The process of analysis followed the procedure described by Hayes (2000)23 with researcher (SH) initially reading the transcripts to identify meaningful units of text. Initial coding for each transcript involved grouping units of text dealing with similar issues into categories and labeling them with a provisional name and definition, this step was undertaken by SH and verified in two transcripts by a second researcher (DB). SH and DB then systematically reviewed the original transcripts to ensure the labels and description assigned to each code were accurately supported by the data. Categories were grouped into emerging themes agreed on by the two researchers (SH and DB) and presented to members of the patient advisory group and the members of the collaborative workshop. The final master themes were settled by SH and DB and thematic mapping was used to develop the relationships between themes.

Phase 2: Quantitative phase

The sample was powered to detect a medium effect size (0.30) for a positive/one-sided correlation.24

The statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS®, version 18.0 for Windows). Relationships between self-reported measures of self-consciousness and the COPD-specific items of self-consciousness and other variables were assessed using Pearson correlations. Due to multiple comparisons, a Bonferroni correction was applied and the significance level was set at p < 0.001. Comparisons between measures of self-consciousness in patients with COPD and healthy controls were performed using independent t test with significance set at p < 0.05.

Results

Phase 1: Qualitative phase

Fifteen individuals agreed to participate in semi-structured interviews. Demographic information was recorded and is displayed in Table 1. Their mean age was 73 years, body mass index 24.7, forced expiratory volume in one second predicted 41.1% and forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) 44.2%.

Table 1.

Patient demographics for Phase 1: Qualitative phase.

| Age (year) | Gender | BMI | FEV1%pred | FEV1/FVC | Smoking status | Pack years | Length of diagnosis (year) | Social status (lives with) | Oxygen usage | Walking aid usage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID. 1 | 72 | M | 19.7 | 29 | 29 | Ex | 50 | 11 | Alone | Yes | Yes |

| ID. 2 | 70 | F | 21.3 | 23 | 37 | Ex | 15 | 8 | Spouse | No | Yes |

| ID. 3 | 66 | F | 20.9 | 25 | 42 | Ex | 10 | 28 | Spouse | Yes | Yes |

| ID. 4 | 63 | M | 35.4 | 30 | 42 | Ex | 60 | 16 | Alone | No | Yes |

| ID. 5 | 78 | F | 23.8 | 45 | 50 | Ex | 20 | 16 | Alone | No | Yes |

| ID. 6 | 68 | M | 25.9 | 29 | 30 | Ex | 100 | 4 | Alone | No | No |

| ID. 7 | 69 | F | 20.7 | 45 | 27 | Ex | 40 | 10 | Spouse | No | Yes |

| ID. 8 | 90 | F | 30.0 | 66 | 68 | Yes | 60 | 14 | Alone | Yes | Yes |

| ID. 9 | 85 | M | 30.1 | 59 | 51 | Ex | 95 | 18 | Alone | No | No |

| ID. 10 | 76 | F | 32.1 | 48 | 73 | Ex | 20 | 17 | Alone | No | Yes |

| ID. 11 | 76 | F | 23.0 | 50 | 58 | Ex | 50 | 10 | Alone | No | Yes |

| ID. 12 | 73 | F | 27.2 | 50 | 30 | Ex | 40 | 4 | Alone | Yes | Yes |

| ID. 13 | 72 | M | 21.5 | 56 | 49 | Ex | 58 | 24 | Spouse | Yes | Yes |

| ID. 14 | 65 | M | 22.2 | 31 | 47 | Yes | 100 | 20 | Alone | Yes | Yes |

| ID. 15 | 68 | F | 16.9 | 30 | 30 | Ex | 40 | 21 | Spouse | No | Yes |

FEV1%pred: forced expiratory volume in one second predicted; FVC: forced vital capacity; BMI: body mass index.

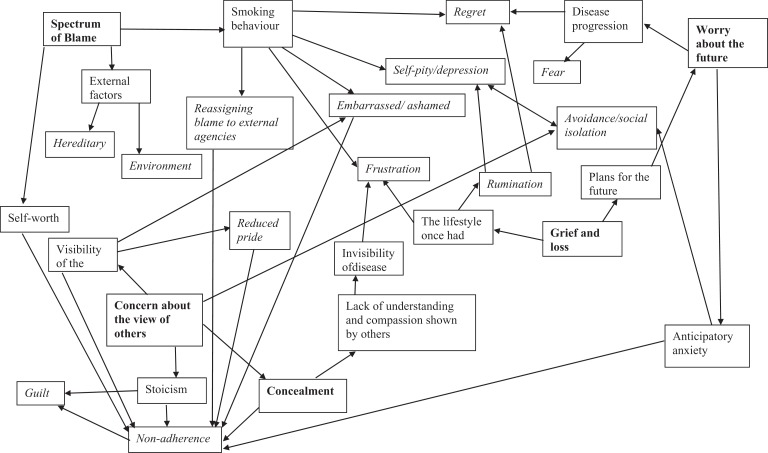

Across the five themes novel interpretations are described in detail and displayed on a thematic map (Figure 1), informed, and contextualized by findings from the previous qualitative investigations. A total of five themes were identified.

Figure 1.

Thematic map of self-conscious emotions.

Grief and loss

Issues surrounding feelings of grief appeared two-fold: patients expressed grief for the person they once were and the things they used to be able to do and they articulated a sense of loss surrounding their inability to fulfill plans they had made for the future.

Patients appeared acutely aware of the constraints on daily activities conferred by their disease, using strong language to portray the value placed on those activities in which they were no longer able to participate and consequent feelings of sadness and frustration:“I love going out to get my wife but I won’t be driving anymore cause I’ve given up my license.” (ID. 1) “And I do miss not gardening. That is my biggest horror … that I can’t get and dig in the dirt.” (ID. 8)

Participants’ transcripts relay accounts of the time and energy spent working to save for retirement and the anticipation of being unable to attain their goals. The excitement of fulfilling these plans appears to compound the sense of loss felt that due to the limitations inflicted by the progression of their disease they were no longer able to complete “I wanted to start an indoor herb garden. That didn’t happen.” (ID. 2).

Spectrum of blame

Blame was discussed by most participants as they made sense of their state of health and its origins and could be construed as a spectrum extending from personal culpability for the development of a chronic and progressive disease to fault from external agencies.

At one end of the spectrum, five individuals readily accepted personal responsibility for their condition “Stupidity. There’s only uh two ways you can get emphysema, smoking and second hand smoke” (ID. 13) and emphasized their compliance with interventions such as, PR and smoking cessation. At polar opposite three participants did not assign any personal responsibility for their condition, ascribing their condition to occupational factors and passive smoking “I really do believe that it is the ceramic dust that has caused it.” (ID. 10).

For those patients expressing personal culpability for COPD dissonance appeared prominent alongside attempts to suppress thoughts or externalize blame. “Hitler’s fault. It’s a poor excuse but everybody smoked in the war.” (ID. 11). These narratives were infused with considerable emotional expressions of shame, self-pity, and regret. “I was full of self-pity and I was very depressed….Oh God, you think to yourself, you know, like you should have had a bag put over your head for being so unintelligent. You know?” (ID. 3), “I’m embarrassed to say that I was a smoker.” (ID. 5).

Concern about the view of others

Participants’ narratives reflect heightened sensitivity to the ways in which they are viewed by others. Concerns were expressed surrounding the ‘visibility’ of the condition with subsequent impact on patients’ sense of well-being and adherence to supportive aids.

COPD seemed to be construed as a socially undesirable condition in terms of the symptoms it provokes “I mean the only thing that bothers me as far as other people go [cough] is my coughing. That can sort of embarrass me. Other than that … It’s gross.” (ID. 6) as well as its impact on physical appearance “It’s disgusting. I don’t like the bruises. Yeah it looks terrible, yeah.” (ID. 4).

Patients’ appeared apprehensive about others evaluation “I’m sure when I get out of a car, people must look at me and think, why is she in handicap parking?” (ID. 6) “one thing I’m told is… should not swallow it. But yet if you’re in a public place what are you supposed to do?” (ID. 13) displaying an acute awareness of the manner in which they must appear and be perceived by others.

Devices which increase the visibility of the disease, namely oxygen and rollers, were described as symbols of disability and aging provoking stoical attitudes. “Because you know I always associated it [rollator] with people who are feeble or old.”(ID. 15). Consequently, participants made attempt to minimize their dependency on aids to preserve an image of independence. “I don’t like using it [rollator]. Like I’ve never used it … when I’ve gone anywhere. Uh that … that maybe it’s uh… that might be a pride thing, I don’t know.” (ID. 6).

Participants noted that even the most facilitative and well-intentioned actions were affected by their use of supports. The behavior and actions of others could be a source of embarrassment and shame surrounding a sense of perceived vulnerability and burdening others. “I was coming home by bus. And I felt too embarrassed to be in there because I was there … people got up and made sure I had a seat, that was… you know, but I felt as if it [rollator] was in the way. And I felt very embarrassed.” (ID. 10).

Yet, other participants expressed gratitude for devices which improved function and enabled independence. “Uh, what the first time I was on oxygen? … I felt great. Yeah because uh … I was struggling all the time. And now I was struggling less. Right? And not all the time.” (ID. 14) “So I traded it [rollator] and got this one and … … I couldn’t care less. That’s how I get out, that’s how I get out.” (ID. 11). For these patients the benefits obtained through the use of these supportive devices appeared to outweigh any self-conscious emotions.

Concealment

Participants describe attempts to hide their disability often driven by expressed guilt for contributing to their condition, and their motivation to retain integrity and appear physically robust. This desire to appear competent seems to overwhelm the need for their disability to be understood by others.

Stoical attitudes are expressed, encouraged by feelings of guilt pertaining to the emotional burden patients see as inflicting on others. “I don’t really talk to … about it too much. I don’t volunteer any information. I try not to say anything to him about it. Just let him know everything is fine, you know” (ID. 4).

Participants’ attempts to conceal their condition seems driven by a desire to appear competent in their current roles, at work, and in the home:

I didn’t tell the truth, I never told a soul at work…. I had to present myself as someone who is extremely capable and keep trucking. I had to prove to yourself and everybody else that there was nothing wrong with me. (ID. 3)

Inability to complete these roles appeared to provoke shame-based emotions and diminished self-worth “Well I have become pretty useless. Uh, you know it’s like when you can’t bend down to pick something up.” (ID 13):

My job meant more to me than most things I did. So when I was no longer to accommodate in my new um … in my new world of uh this …uh … office uh, it limited my ability to feel that I was accomplishing the producing part of my life and that took a real toll. (ID. 3)

While hiding their condition permitted patients to maintain their identity and sense of self-worth, frustration was expressed at the lack of awareness and compassion shown by others:

it’s not a nice disease and it’s hidden too, so a lot of people don’t know you are sick and … … going up the stair I’ll stop at the mall and they … they try to push you out of the way. (ID. 4)

Concealment seemed accompanied by social comparisons to others with COPD which served to minimize the significance of their own disease state. “So other people may have something. There are some people there that are really ill.” (ID 9) “I mean, with the different ones in the group you always feel worse yourself until you are with a group and see other people and you then feel that you are not as bad as they are.” (ID 13). Patients readily accepted delays in their care, emphasizing the urgency of attending to other patients’ needs before their own, believing their own condition to be less serious, and or/life threatening and being unable or unwilling to assert themselves. “I would think they would deal with the heart attack and stroke before me. Would think it’s a bit more serious, whereas with me I would expect I guess, me being me, they could always give me a mask temporarily.” (ID. 7)

Worry about the future

Patients’ narratives portrayed a sense of threat which was both imminent and yet stretched into the future.

Patients appeared hypervigilant to their disease state voicing catastrophic cognitions concerning the effects of certain actions and activities “I do often think, what else can happen? Gonna … gonna faint all of a sudden?” (ID. 8), “I get a little anxious especially when I am going home …. I get anxious, my heart starts racing cause I realize okay … especially in the winter. Put on a coat, put on the boots … even if it’s summer I guess.” (ID. 15). Such anxieties appeared to result in avoidance of activities for fear that it would prompt undesirable symptoms “If the situation required me to exert a lot. I wouldn’t do it.” (ID. 7).

The progressive nature of the disease seemed to provoke feelings of worry and uncertainty about what the future will hold “where is this going? You know what I mean? How bad is it going to get or how worse it’s going to get.” (ID. 5). Such concerns appeared to limit individuals’ ability to be spontaneous and live the lifestyle once known “Yep, it still affects my confidence because I travelled. And uh … I had fears of not being able to get myself from point A to point B due to my limitations.” (ID. 3)

Phase 2: Quantitative phase

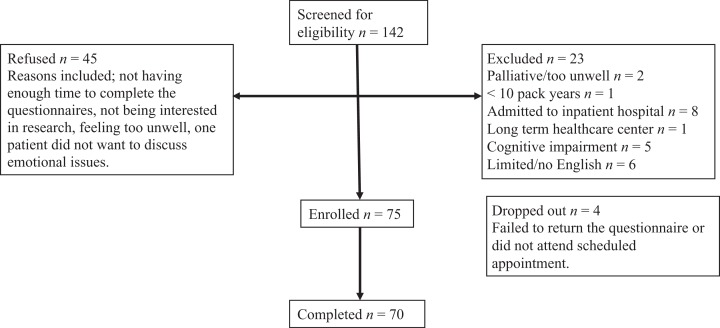

Individuals with COPD

Recruitment and patient demographics are reported in Figure 2 and Table 2, respectively. Seventy individuals with COPD completed the questionnaires.

Figure 2.

Recruitment diagram for Phase 2: Quantitative Phase, individuals with COPD. COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[GQ: Please ensure that you have obtained and enclosed all necessary permissions for the reproduction of artistic works, (e.g. illustrations, photographs, charts, maps, other visual material, etc.) not owned by yourself. Please refer to your publishing.

Table 2.

Between group differences in characteristics between individuals with COPD and healthy controls.

| Individuals with COPD (n = 70); mean (SD) | Healthy controls (n = 61); mean (SD) | Between group differences | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 70.8 (9.4) | 66.2 (12.9) | p = 0.33 |

| Gender (%male) | 44 | 34 | p = 0.23 |

| BMI | 25.2 (6.3) | 25.8 (4.9) | p = 0.617 |

| FEV1%pr | 40.5 (18.8) | 89.2 (28.0) | p < 0.001 |

| FEV1/FVC | 43.5 (14.4) | 76.4 (7.5) | p < 0.001 |

| Smoking status (%yes, ex, no) | 5.7 | 4.9 | p < 0.001 |

| 94.3 | 18.0 | ||

| 0 | 77.0 | ||

| Pack years | 43.5 (21.7) | 2.8 (7.3) | p < 0.001 |

| Length of diagnosis (y) | 8.8 (6.7) | ||

| Number of co-morbidities (COPD) or chronic conditions (healthy controls) | 2.7 (2.0) | 1.1 (1.4) | p < 0.001 |

| Social status (lives with) (% alone spouse, family, other) | 37.7 | 28.3 | p = 0.004 |

| 37.1 | 58.3 | ||

| 24.3 | 10.0 | ||

| 1.4 | 3.3 | ||

| Oxygen usage (% yes) | 44.3 | ||

| Walking aid usage (% yes) | 51.4 | ||

| Previous PR (% yes) | 75.7 |

SD: standard deviation, BMI: body mass index; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second; FEV1/FVC: forced expiratory volume in one second/forced vital capacity, PR: pulmonary rehabilitation.

Healthy controls

Sixty-three healthy individuals agreed to participate. Two were excluded from the data analysis because they had abnormal spirometry (FEV1% predicted <80% or FEV1/FVC < 70%) leaving 61 subjects to complete the questionnaires. Five subjects were unable to perform the spirometry testing correctly but were included on the basis they had no history of smoking or respiratory compromise. Subject characteristics (n = 61) are displayed in Table 2.

Associations with health outcomes

Self-reported measures of self-consciousness, including the COPD-specific items of self-consciousness, correlated with each other (all p < 0.01). Relationships between measures of self-consciousness and the COPD-specific items of self-consciousness with health outcomes, including HRQOL, self-efficacy, anxiety, and depression, are displayed in Table 3. The BFNE, the SCS-SF, the shame, and pride domains of the SGS and the disease-specific items all significantly correlated with the mastery and emotion domains of the CRQ-SR and the anxiety and depression domains of the HADS (all p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Significant correlations between self-conscious emotions and HRQOL, self-efficacy, and psychological symptoms (Persons r).

| CRQ-SR: dyspnoea | CRQ-SR: fatigue | CRQ-SR: mastery | CRQ-SR: emotions | PRAISE | HADS: anxiety | HADS: depression | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BFNE | NS | NS | r = −0.47a | r = −0.60a | NS | r = 0.60a | r = 0.49a |

| SCS-SF | NS | NS | r = 0.41a | r = 0.55a | NS | r = −0.50a | r = −0.51a |

| SGS: Guilt | NS | NS | NS | r = 0.45a | NS | r = −0.47a | NS |

| SGS: Shame | NS | NS | r = 0.52a | r = 0.65a | NS | r = −0.70a | r = −0.56a |

| SGS: Pride | NS | NS | r = −0.50a | r = −0.57a | NS | r = 0.58a | r = 0.61a |

| COPD-specific items of self-consciousness | NS | NS | r = 0.58a | r = 0.65a | NS | r = −0.51a | r = −0.55a |

BFNE: brief fear of negative evaluation; SCS-SF: self-compassion scale-short form; SGS: Adapted Shame and Guilt Scale; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PRAISE: pulmonary rehabilitation adapted index of self-efficacy; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; CRQ-SR: Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire-Self-Reported; HROQL: health-related quality of life; NS: not significant.

aDue to multiple comparisons significance levels were set at p < 0.001.

Self-conscious emotions in individuals with COPD and healthy controls

Differences between scores obtained on measures of self-conscious emotions in individuals with COPD compared to healthy controls are displayed in Table 4. The healthy controls displayed greater fear of negative evaluation than individuals with COPD. Individuals with COPD appeared less compassionate toward themselves and reported higher levels of shame and reduced pride compared to healthy controls (all p < 0.05). There were no between-group differences in levels of guilt.

Table 4.

Self-conscious emotions in individuals with COPD compared to healthy controls.a

| Measures of self-conscious emotions | COPD (n = 70); mean (SD) | Healthy controls (n = 59);b mean (SD) | Between-group differences |

|---|---|---|---|

| BFNE | 27.8 (10.5) | 30.9 (7.2) | p = 0.046a |

| SCS-SF | 3.3 (0.6) | 3.6 (0.7) | p = 0.010a |

| SGS—Guilt | 18.8 (4.3) | 18.6 (3.4) | p = 0.808 |

| SGS—Shame | 21.3 (3.9) | 23.0 (2.8) | p = 0.006a |

| SGS—Pride | 12.3 (4.03) | 10.3 (3.2) | p = 0.001a |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SD: standard deviation; BFNE: brief fear of negative evaluation, SCS-SF: Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form, SGS: Adapted Shame and Guilt Scale.

aSignificance levels were set at p < 0.05.

bTwo people did not complete the questionnaires fully and were therefore excluded from the analysis.

Discussion

This mixed-methods study offers information on a number of self-conscious emotions including not only reported shame, guilt, and self-blame but also fear of negative evaluation, reduced self-compassion, and diminished pride, which have not previously been evaluated in individuals with COPD. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assesses self-conscious emotions using questionnaires offering information on a large representative cohort and enabling exploration of associations with other health outcomes. It is also the first time comparisons have been made between self-conscious emotions reported by those with COPD and healthy elderly individuals.

The findings from this study echo previous literature in which self-blame and personal culpability are prominent in the narratives of individuals with COPD.7–9 Self-blame has been associated with negative emotional responses including feeling shamed, disgraced, depressed, and embarrassed, leading to reduced help-seeking, reduced adherence to oxygen therapy, and social isolation.7,11,12 Self-conscious emotions are also reported in conjunction with negative feelings of dependency on people and on devices, which force patients to reappraise their identity within the context of their disease. Such critical self-appraisals negatively influence self-confidence and challenges feelings of self-worth,6 which may lead to reduced active engagement with interventions as patients feel undeserving of dedicated care.13 Feelings of worthlessness may also mean patients have difficulty asserting themselves. They describe feeling they have no right to complain especially when dealing with health care professionals.6 Shaming attributes may arise from interactions with health care professionals, who believe patients with COPD are to blame for their disease, resulting in patients feeling stigmatized.8,10 Therefore, health care professionals need to be mindful of interactions with patients; taking the time to listen uncritically may enhance patients’ self-control and feelings of self-worth.25

Self-conscious emotions have not previously been assessed objectively in individuals with COPD. Such emotions were strongly associated with reduced mastery, a heightened emotional response, and elevated symptoms of anxiety and depression, detectable both by the general measures of self-consciousness and the disease-specific items. Interestingly, the PRAISE data did not correlate with any assessment of self-conscious emotions. Yet, the mastery domain of the CRQ-SR correlated with five. It is likely that self-conscious emotions stem from individuals’ perceptions of their disease and the CRQ-SR domain assesses mastery specific to an individuals’ illness and breathing problems within the past 2 weeks. By contrast, the PRAISE assesses general feelings of self-efficacy and those related to one’s perceived ability to complete PR.

This is the first study to apply these objective measures of self-compassion, shame, and guilt to a population of older adults living with chronic disease. Patients with COPD were found to be less compassionate toward themselves than healthy controls of a similar age, and both populations in this study scored lower than scores reported in younger adults aged 17–36 years.17

The vast majority of patients expressed feelings of guilt during the interviews and identified their “own behavior” as being responsible for their lung disease, yet questionnaire-assessed guilt did not discriminate healthy individuals and those with COPD. Given that guilt is rarely experienced on the conscious level, it may be difficult to detect using self-reported measures.26 Although it has been reported in the narratives of individuals newly diagnosed with COPD,27 it is unclear whether feelings of guilt remain salient 8 years following diagnosis. This may explain why heightened guilt and depression were not significantly correlated despite functional magnetic resonance imaging demonstrating the proneness of individuals with depression to exaggerate feelings of guilt.28

This study is not without its limitations. The infrequent application of the self-conscious measures in those with COPD, in particular the SGS, makes it difficult to contextualize our results in comparison with other chronic disease populations. This measure was chosen as it considers three important dimensions (shame, guilt, and pride), two of which (shame and pride) are strongly associated with important health outcomes. Given the number of correlations, the chance of significant correlation was high. However, even after correction for multiple correlations, all self-conscious emotions, with the exception of guilt, were significantly associated with reduced mastery, a heightened emotional response, and psychological symptoms.

Our observations suggest a need to scope and address self-conscious emotions in individuals with COPD. Therapies to target self-conscious emotions include compassion-focused therapy29 and mindfulness.30 Self-compassion, as a key component of mindfulness, has been reported to mediate the effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression supporting Gilbert’s model (2010) of self-compassion as a mediator for psychological affect.31,32 A pilot-randomized controlled trial of an 8-week Mindful Self-Compassion program delivered to community adults (mean age 51 years) noted significant differences in favor of the intervention group in self-compassion, mindfulness, life satisfaction, depression, anxiety, stress, and avoidance with these benefits evident 12 months.33 Such interventions have the potential to improve well-being, reduce psychological symptoms, and encourage effective disease strategies. Although disease-specific self-conscious items still require psychometric testing prior to broader application in the COPD population, the items correlated well with other general measures of self-consciousness and with important health outcomes. They were simple to apply and well accepted by individuals with COPD.

Conclusion

Patient narratives reflected low levels of self-compassion, high self-judgment, and diminished self-worth, known to negatively impact on help-seeking behavior and adherence to active interventions. Self-conscious emotions are prominent and were associated with reduced mastery, heightened emotions, and elevated symptoms of anxiety and depression. Individuals with COPD were less compassionate toward themselves, had higher levels of shame, and lower levels of pride compared with healthy controls of a similar age. An improved awareness of self-conscious emotions will enable targeted therapy aimed at improving mastery and reducing psychological symptoms.

Footnotes

Author Note: Samantha L Harrison is currently affiliated to School of Health and Social Care, Teesside University, Middlesbrough, UK.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by the Canadian Lung Association, Canadian Respiratory Health Professionals, and DB holds a Canadian Research Chair.

Supplemental material: The online data supplements are available at http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/suppl/10.1177/1479972316654284.

References

- 1. Nici L, Donner C, Wouters E, et al. American thoracic society/European respiratory society statement on pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 173(12): 1390–39012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Williams V, Bruton A, Ellis-Hill C, et al. What really matters to patients living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? An exploratory study. Chron Respir Dis 2007; 4(2): 77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yohannes AM, Willgoss TG, Baldwin RC, et al. Depression and anxiety in chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, relevance, clinical implications and management principles. Int J Geriat Psychiatry 2010; 25(12): 1209–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brown JD, Marshall MA. Self-esteem and emotion: some thoughts about feelings. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2001; 27(5): 575–584. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guthrie SJ, Hill KM, Muers ME. Living with severe COPD. A qualitative exploration of the experience of patients in Leeds. Respir Med 2001; 95(3): 196–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lindqvist G, Hallberg LR. ‘Feelings of guilt due to self-inflicted disease’: a grounded theory of suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). J Health Psychol 2010; 15(3): 456–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Arne M, Emtner M, Janson S, et al. COPD patients perspectives at the time of diagnosis: a qualitative study. Prim Care Respir J 2007; 16(4): 215–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Berger BE, Kapella MC, Larson JL. The experience of stigma in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. West J Nurs Res 2011; 33(7): 916–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Halding AG, Heggdal K, Wahl A. Experiences of self-blame and stigmatisation for self-infliction among individuals living with COPD. Scand J Caring Sci 2011; 25(1): 100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Winstanley L. Risk assessment documentation in COC prescribing. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2008; 34(2): 137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Earnest MA. Explaining adherence to supplemental oxygen therapy: the patient’s perspective. J Gen Intern Med 2002; 17(10): 749–755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clancy K, Hallet C, Caress A. The meaning of living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Nurs Healthc Chronic Illn 2009; 1(1): 78–86. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Harrison SL, Robertson N, Apps L, et al. “We are not worthy” understanding why patients decline pulmonary rehabilitation following an acute exacerbation of COPD. Disabil Rehabil 2015; 37(9): 750–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Leary MR. A brief version of the Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 1983; 9(3): 371–375. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Collins KA, Westra HA, Dozois DJ, et al. The validity of the brief version of the fear of negative evaluation scale. J Anxiety Disord 2005; 19(3): 345–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marschall D, Sanftner JP, Tangney JP. The State Shame and Guilt Scale. Fairfax: George Mason University, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Raes F, Pommier E, Neff KD, et al. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clin.PsycholPsychother 2011; 18: 250–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Neff K. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity 2003; 2(3): 223–250. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Williams JE, Singh SJ, Sewell L, et al. Development of a self-reported Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ-SR). Thorax 2001; 56(12): 954–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Williams JE, Singh SJ, Sewell L, et al. Health status measurement: sensitivity of the self-reported Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ-SR) in pulmonary rehabilitation. Thorax 2001; 58(6): 515–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vincent E, Sewell L, Wagg K, et al. Measuring a change in self-efficacy following pulmonary rehabilitation: an evaluation of the PRAISE tool. Chest 2011; 140(6): 1534–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 1983; 67(6): 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haynes N. Doing Psychological Research. Buckingham: Open University Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol.Bull 1992; 112(1): 155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Torheim H, Kvangarsnes M. How do patients with exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease experience care in the intensive care unit? Scand J Caring Sci 2014; 28(4): 741–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Strang S, Farrell M, Larsson LO, et al. Experience of guilt and strategies for coping with guilt in patients with severe COPD: a qualitative interview study. J Palliat Care 2014; 30(2): 108–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lindgren S, Storli SL, Wiklund-Gustin L. Living in negotiation: patients’ experiences of being in the diagnostic process of COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2014; 6(9): 441–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Green S, Lambon Ralph MA, Moll J, et al. Guilt-selective functional disconnection of anterior temporal and subgenual cortices in major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012: 69(10): 1014–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gilbert P. Introducing compassion-focused therapy. Adv Psychiatr Treat 2009; 15(3): 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kabat-Zinn J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen HospPsychiatry 1982; 4(1): 33–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kuyken W, Watkins E, Holden E, et al. How does mindfulness-based cognitive therapy work? Behav Res Ther 2010; 48(11): 1105–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gilbert P. An introduction to compassion focused therapy in cognitive behavior therapy. J Cog Psychother 2010; 3(special section): 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Neff KD, Germer CK. A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. J ClinPsychol 2013; 69(1): 28–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]