Abstract

Objectives:

Physical activity, sedentary and sleep behaviours have strong associations with health. This systematic review aimed to identify how clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) report specific recommendations and strategies for these movement behaviours.

Methods:

A systematic search of databases (Medline, Scopus, CiNAHL, EMbase, Clinical Guideline), reference lists and websites identified current versions of CPGs published since 2005. Specific recommendations and strategies concerning physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep were extracted verbatim. The proportions of CPGs providing specific recommendations and strategies were reported.

Results:

From 2370 citations identified, 35 CPGs were eligible for inclusion. Of these, 21 (60%) provided specific recommendations for physical activity, while none provided specific recommendations for sedentary behaviour or sleep. The most commonly suggested strategies to improve movement behaviours were encouragement from a healthcare provider (physical activity n = 20; sedentary behaviour n = 2) and referral for a diagnostic sleep study (sleep n = 4).

Conclusion:

Since optimal physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep durations and patterns are likely to be associated with mitigating the effects of COPD, as well as with general health and well-being, there is a need for further COPD-specific research, consensus and incorporation of recommendations and strategies into CPGs.

Keywords: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung diseases obstructive, clinical practice guideline, disease management, sedentary lifestyle

Background

Throughout the day, people engage in a range of activities: sleep, leisure, occupational, transport, self-care or household chores.1 Activities can be categorized into different movement behaviours according to their energy requirement in metabolic equivalents (METs). While the energy requirement of sleeping is around 0.9 METs, the energy requirement of waking activities ranges from 1.0 MET for quiet sitting to >20 METs for athletic activities. Waking activities that are on the lower end of the energy expenditure spectrum (1.0–1.5 METs) and maintain a seated or reclined posture are considered sedentary behaviours.1,2 In contrast, physical activities are bodily movements produced by skeletal muscles that result in energy expenditure and can be of light- (1.6–2.9 METs), moderate- (3–5.9 METs) or vigorous-intensity (≥6 METs).1,3

Different movement behaviours have significant associations with either positive or negative health outcomes.4–6 Public health guidelines have been developed to provide the general population with specific recommendations for movement behaviours and strategies to facilitate changes in movement behaviours, to improve and maintain health.7–9

For the general population, 150 minutes of at least moderate intensity (≥3 METs) physical activity per week is recommended for significant health benefits;8 however, for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), replacing time spent in sedentary behaviour with light intensity physical activities may be a more feasible goal.10 Reducing time spent in sedentary behaviour has demonstrated positive associations with waist circumference and glucose level,11 while participation in regular physical activity has shown associations with reduced risk of all cause and respiratory mortality and acute COPD exacerbation.12 Spending more time in active pursuits may also help to improve sleep quality.13 Sleep quality has shown to be a predictor of mortality, COPD-hospitalization, health-related quality of life and severity of day time symptoms.14–16

Public health guidelines developed for the general population recommend people who have chronic conditions seek advice from health care providers to adequately manage their condition.8 To assist with the management of chronic conditions such as COPD, clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) have been developed.17,18 This systematic review posed two primary questions:

In CPGs for the management of COPD:

What specific recommendations are provided for physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep?

What strategies are provided to achieve optimal amounts of physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep?

Secondary questions concerned how specific recommendations and strategies for movement behaviours were presented within CPGs.

Methods

The protocol for this systematic review was developed using the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA-P 2015) guidelines.19

Eligibility

CPGs were included in this review if they were the most recent version for the broader management of COPD developed by an authoritative body and published since 2005. No limitations were set for language of publication. References were excluded if they were experimental or observational designs, systematic or narrative reviews, conference abstracts, opinion pieces or focused specifically on pharmacological management, management of acute exacerbations, pulmonary rehabilitation or domiciliary oxygen.

Information sources and search strategy

A range of electronic databases were searched: OVID Medline, EMbase, CiNAHL and Scopus. Search terms were collated for the population of interest (COPD) and the publication type (clinical practice guideline). The first group of search terms included COPD, pulmonary emphysema and pulmonary disease chronic obstructive. The second group of search terms included guideline, consensus, position statement, guidance and standard. All items within a group were separated by the Boolean term ‘OR’ and groups were separated by the Boolean word ‘AND’. The complete search strategy conducted in OVID Medline is presented in Table S1 of the online supplementary materials. Clinical guideline databases were also searched for eligible guidelines and included: The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Clinical Practice Guidelines Portal, National Guideline Clearing House, International Guideline Network, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network and the International Primary Care Respiratory Group. To identify any additional guidelines, the reference lists of systematic reviews identified from the search and websites of the medical and scientific bodies listed as participating at the European Respiratory Society International Congress for 2016 were screened. An expert in the field was consulted to ensure that no known CPGs were missed in the search process.

Document selection

The complete lists of titles retained from the searches were screened (HL). Where eligibility was unclear from the title or abstract, the full text was reviewed by two independent reviewers and assessed against eligibility criteria (HL, MTW). For all titles and/or abstracts that were not published in English, the full texts were obtained. A single reviewer (HL) assisted a fluent speaker of the language to assess non-English texts against eligibility criteria.

Data collection

A data extraction template was developed a priori. For eligible CPGs published in English, three reviewers (HL, MTW and TWE) extracted data independently; data were then compared and discussed until consensus was met. For eligible CPGs not published in English, a single reviewer (HL) assisted a fluent speaker of the language to extract data. Data extracted from CPGs are described in Box 1. Where data were extracted regarding specific recommendations and strategies, the following definitions were applied:

Box 1.

Data extracted from clinical practice guidelines.

| Guideline demographics | Title, developing medical/scientific/government body, country of origin, year, version/edition |

| Content | Specific recommendations for physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep including type, context, intensity, duration, frequency, pattern and/or bout (verbatim) |

| Strategies provided to achieve optimal amounts of physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep (verbatim) | |

| Presentation of movement behaviours | Whether the guideline had a section for: physical activity, sedentary behaviour or sleep (yes/no) |

| For CPGs published in English: frequency with which the term ‘activ*’ (in context of physical/daily activity, non-pharmacological management only), ‘sedentar*’ and ‘sleep’ (in context of sleep quality) were mentioned within the main body or appendices |

Specific recommendation: Where a target type, context, intensity, frequency, duration, pattern and/or bout of a movement behaviour was reported/stated.

Strategy: Where a method, intervention or process was reported/stated as a means of changing a movement behaviour.

Data analysis

All data extracted were collated and summarized descriptively for specific recommendations or strategies according to movement behaviour type. The proportion of CPGs providing specific recommendations and strategies for each movement behaviour was reported. Specific recommendations and strategies around movement behaviours were compared for commonalities across guidelines. How movement behaviours were presented within CPGs was reported descriptively.

Results

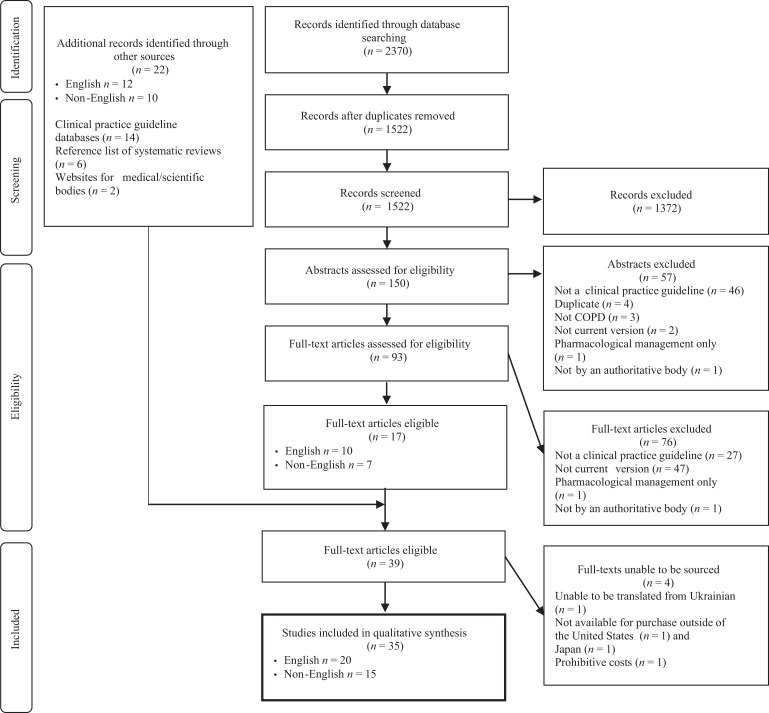

The initial search of four electronic databases obtained 2370 citations, 17 of which were eligible for inclusion. A further 22 citations were identified through supplemental search approaches. No additional guidelines were identified or removed following consultation with the content expert. Despite meeting eligibility criteria for inclusion, one CPG was excluded as the full text was unable to be translated from Ukrainian,20 and three were excluded as the full texts were unable to be obtained (not being available for purchase outside of the United States of America21 and Japan22 and prohibitive costs23). Therefore, 35 CPGs were included in this review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Outcome of search strategy leading to clinical practice guidelines for the management of COPD eligible for this review. COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Physical activity

There were 21 (60%) CPGs included in this review, which provided specific recommendations for physical activity (target: type n = 7, 20%; context n = 4, 11%; intensity n = 6, 17%; duration n = 6, 17%; frequency n = 19, 54%; Table 1). Walking was the most commonly recommended type of physical activity (n = 4, 11%), followed by cycling (n = 3, 9%), strength training (n = 3, 9%) and non-specific aerobic training (n = 3, 9%). Four (11%) guidelines recommended a context for which physical activity is to be performed; as part of the person’s lifestyle and social life,46 in a group47 or in recreational clubs,48 at home49 or independently.48 Four of the six guidelines, which provided specific recommendations for intensity of physical activity, recommended people with COPD to be active as per their capacity or until breathless.48,50–52 The six guidelines including a target duration of physical activity, recommended durations ranging from 20 minutes to 45 minutes per day. One guideline provided a specific target duration for people with more severe COPD, recommending short intervals rather than continuous activity.53 Specific recommendations for a target frequency ranged from once a week (n = 1, 3%) to daily (n = 6, 17%) or regularly (n = 8, 23%; Table 1). Three guidelines recommended regular supervision.47,48,54

Table 1.

Specific recommendations for physical activity within COPD CPGs.

| Clinical practice guideline (n = 21) | English? (Y/N) | Type (n = 7) | Context (n = 4) | Intensity (n = 6) | Duration (n = 6) | Frequency (n = 19) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOLD: International24 | 2015 | Y | – | – | – | – | Daily |

| COPD-X: Australia and NZ25 | 2015 | Y | – | – | – | – | Regular |

| NHG: the Netherlands26 | 2015 | N | Intensive walking, swimming, cycling, fitness | – | – | 30 min/d | Daily |

| ALAT: Latin America27 | 2015 | N | – | – | – | 30 min/d | ≥ 3 times/week |

| Socialstyrelsen: Sweden28 | 2015 | N | Cardio, strength | – | Based on physical capacity assessed with 6MWT | – | – |

| AIMAR: Italy29 | 2014 | Y | – | – | – | – | Regular |

| SEPAR: Spain30,31 | 2014 | Y | – | – | – | 20–30 min/d Severe disease Short intervals | Daily |

| VA/DoD: USA32 | 2014 | Y | – | – | – | – | Regular |

| SGP: Switzerland33 | 2013 | Y | – | At home | – | – | Regular |

| CPFS: Czech Republic34 | 2013 | Y | – | – | – | – | Regular |

| Ministerio de Salud: Chile35 | 2013 | N | – | – | – | – | Regular |

| ICS/NCCP: India36 | 2013 | Y | – | – | As per capacity | – | Daily |

| Directorate of Health: Norway37 | 2012 | N | Strength and aerobic | – | – | – | Daily |

| AAMR: Argentina38 | 2012 | N | Treadmill, cycle ergometer, walking, ramps or stairs with walkers | As part of lifestyle or social life | – | – | Regular |

| SAPP: Algeria39 | 2012 | N | – | – | – | 30-45 min/d | ≥ 5 times/week |

| SPLF: France40 | 2010 | N | Chosen by patient, strength, balance, flexibility | Independent/ recreational clubs | Sufficient intensity (dyspnoea threshold) | 30–45 min/d | ≥ 3 times/week Supervision once/week |

| NVALT: Netherlands41 | 2010 | N | – | In a group | – | – | ≥ Once/week Supervision once/week |

| MOH: Malaysia42 | 2009 | Y | – | – | Maintain best level | – | – |

| Health Authority: Denmark43 | 2007 | N | Nordic walking, cycling, ball games, activities where large muscles are activated | – | 60–90% VO2 max. | 20–30 min/d | 3–4 times/week supervision weekly or monthly |

| CTS: Canada44 | 2007 | Y | – | – | – | – | Regular |

| IPCRG: International45 | 2006 | Y | Walking, lower limb exercises | – | Until breathless | – | Daily |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPGs: clinical practice guidelines; 6MWT: six minute walk test; VO2 max: maximal oxygen uptake. For explanation of CPG abbreviation see Table S2 of the online supplementary materials.

There were 28 (80%) CPGs that provided strategies to achieve improvements in physical activity. Encouragement from a health care provider was the most commonly suggested strategy (n = 20, 57%) followed by education (n = 11, 31%), long-term management (n = 6, 17%) and referral to an exercise training program (n = 6, 17%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Non-pharmacological strategies to achieve optimal amounts of physical activity for people with COPD included in CPGs.

| Strategy | Clinical practice Guideline | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOLD: International24 | COPD-X: Australia and NZ25 | NHG: Netherlands26 | ALAT: Latin America27 | FERS: Russia55 | Socialstyrelsen: Sweden28 | AIMAR: Italy29 | SEPAR: Spain30 , 31 | Duodecim/FERS: Finland56 | PTChP: Poland57 | HAS: France58 | VA/DoD: USA32 | STS: Saudi Arabia59 | SGP: Switzerland33 | CPFS: Czech Republic34 | ICSI: USA60 | Ministerio de Salud: Chile35 | ICS/NCCP: India36 | Directorate of Health: Norway37 | Michigan: USA61 | AAMR: Argentina38 | SAPP: Algeria39 | ATS/ERS: USA/Europe62 | British Columbia: Canada63 | INER: Mexico44 | SATS: South Africa64 | SPLF: France40 | NICE: UK65 | NVALT: Netherlands41 | MOH: Malaysia42 | DGP: Germany66 | Health Authority: Denmark43 | CTS: Canada44 | IPCRG: International67 | Texas: USA68 | Total number of CPGs | |

| Available in English? (Y/N) | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | |

| Encouragement from physician | 20 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | 11 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Long-term management | 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Referral for exercise training | 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Supplemental oxygena | 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| OT/energy conservation | 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Strategies to facilitate physical activity | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Multidisciplinary care | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Supervised maintenance program | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Unsupervised/unspecified maintenance program | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physiotherapy/EP mgmt. | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Repeat PR | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Community programs | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Breathing exercises | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Early intervention | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Individual counselling | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Referral to specialist | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPGs: clinical practice guidelines; EP: exercise physiologist; mgmt:– management; OT: occupational therapy; PR: pulmonary rehabilitation

aOxygen recommended on exertion for those patients who meet specific recommendations for hypoxia. For explanation of CPG abbreviation see Table S2 of the online supplementary materials.

Note: Shading indicates that the corresponding strategy was provided in the CPG.

Guidelines were similar in reporting specific recommendations and strategies for physical activity whether published in English (specific recommendations n = 10, 50%; strategies n = 17, 85%) or a language other than English (specific recommendations n = 11, 73%; strategies n = 12, 80%).

Three guidelines (9%) had a dedicated section for physical activity (Table 4). Of the guidelines published in English, the term ‘activ*’ was most frequently mentioned in the guidelines from Australia and New Zealand (n = 29), GOLD (n = 24) and Spain (n = 21). The terms pertaining to physical activity were mentioned more frequently in the CPGs published in 2014 or later.

Table 4.

Format and frequency of recommendations and strategies for physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep within English CPGs.

| Dedicated section/chapter? | Number of times terms mentioned within main body/appendices | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical practice guideline (n = 20) | Physical activity | Sedentary behaviour | Sleep | Activa | Sedentarb | Sleepc | |

| GOLD: International24 | 2015 | Yes | 24 | 0 | 4 | ||

| COPD-X: Australia and NZ25 | 2015 | Yes | Yes | 29 | 4 | 16 | |

| FERS: Russia55 | 2015 | 14 | 0 | 7 | |||

| AIMAR: Italy29 | 2014 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |||

| SEPAR: Spain30 | 2014 | Yes | 21 | 1 | 0 | ||

| VA/DoD: USA32 | 2014 | 6 | 0 | 5 | |||

| STS: Saudi Arabia59 | 2014 | Yes | 1 | 0 | 11 | ||

| SGP: Switzerland33 | 2013 | 3 | 0 | 4 | |||

| CPFS: Czech Republic34 | 2013 | 4 | 0 | 2 | |||

| ICSI: USA60 | 2013 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |||

| ICS/NCCP: India36 | 2013 | 6 | 0 | 2 | |||

| Michigan: USA61 | 2012 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| ATS/ERS: USA/Europe62 | 2011 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||

| British Columbia: Canada63 | 2011 | 3 | 0 | 2 | |||

| SATS: South Africa64 | 2011 | Yes | 1 | 0 | 3 | ||

| NICE: UK65 | 2010 | 9 | 0 | 2 | |||

| MOH: Malaysia42 | 2009 | 6 | 0 | 1 | |||

| CTS: Canada44 | 2007 | 7 | 0 | 5 | |||

| IPCRG: International45 | 2006 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Texas: USA68 | 2006 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||

CPGs: clinical practice guidelines; GOLD: Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; COPD-X: Australian and New Zealand online management guidelines for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; AIMAR: Interdisciplinary Association for Research in Lung Disease; SEPAR: Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery; VA/DoD: Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense; STS: Specialized Technical Services; SGP: Swiss Respiratory Society; CPFS: Czech Pneumological and Phthisiological Society; ICS/NCCP: The Indian Chest Society/National College of Chest Physicians; ATS/ERS: American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society; SATS: South African Theological Seminary; NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; MOH: Ministry of Health; IPCRG: The International Primary Care Respiratory Group

aactiv = physical/daily activity in context of non-pharmacological management.

bsedentar = sedentary/sedentarism.

csleep = in context of sleep quality.

Sedentary behaviour

No CPG provided specific recommendations for sedentary behaviour.

Three (9%) CPGs provided strategies to reduce time spent in sedentary behaviour. Encouragement from a health care provider was suggested by two guidelines, and inclusion of practicing sit-to-stand transitions in exercise training was suggested by a single guideline (Table 3). Of the 15 non-English guidelines included in this review, only one provided strategies to reduce time spent in sedentary behaviour,69 which differed from those provided in English guidelines.

Table 3.

Non-pharmacological strategies to achieve optimal amounts of sedentary and sleep behaviours for people with COPD within CPGs.

| Strategy | Clinical practice guideline | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOLD: International24 | COPD-X: Australia and NZ25 | NHG: Netherlands26 | ALAT: Latin America27 | FERS: Russia55 | Socialstyrelsen: Sweden28 | AIMAR: Italy29 | SEPAR: Spain30,31 | Duodecim/FERS: Finland56 | PTChP: Poland57 | HAS: France58 | VA/DoD: USA32 | STS: Saudi Arabia59 | SGP: Switzerland33 | CPFS: Czech Republic34 | ICSI: USA60 | Ministerio de Salud: Chile35 | ICS/NCCP: India36 | Directorate of Health: Norway37 | Michigan: USA61 | AAMR: Argentina38 | SAPP: Algeria39 | ATS/ERS: USA/Europe62 | British Columbia: Canada63 | INER: Mexico44 | SATS: South Africa64 | SPLF: France40 | NICE: UK65 | NVALT: Netherlands41 | MOH: Malaysia42 | DGP: Germany66 | Health Authority: Denmark43 | CTS: Canada44 | IPCRG: International67 | Texas: USA68 | Total number of CPGs | |

| Available in English? (Y/N) | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | |

| Sedentary behaviour | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Encouragement from physician | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Targeted exercise training | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sleep | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Diagnostic sleep study | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Referral to sleep specialist | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Supplemental oxygena | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| NIV | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPGs: clinical practice guidelines; NIV: non-invasive ventilation; COPD-X: Australian and New Zealand online management guidelines for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; AIMAR: Interdisciplinary Association for Research in Lung Disease; SEPAR: Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery; VA/DoD: Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense; STS: Specialized Technical Services; SGP: Swiss Respiratory Society; CPFS: Czech Pneumological and Phthisiological Society; ICS/NCCP: The Indian Chest Society/National College of Chest Physicians; ATS/ERS: American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society; SATS: South African Theological Seminary; NICE: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; MOH: Ministry of Health; IPCRG: The International Primary Care Respiratory Group

aNocturnal oxygen is recommended for those patients who meet specific guidelines for long-term domiciliary oxygen therapy

No guideline had a dedicated section for sedentary behaviour (Table 4). Of the guidelines published in English, the term ‘sedentar*’ was most frequently mentioned in the guidelines from Australia and New Zealand (n = 4), with the guidelines from Spain and Italy both mentioning the term once each.

Sleep

No CPG provided specific recommendations for sleep.

Five (14%) CPGs provided strategies to improve sleep. Referral for a diagnostic sleep study (n = 4, 11%) or to a sleep specialist (n = 2, 6%) were the most commonly suggested strategies (Table 3). All guidelines providing strategies to improve sleep were published in English.

Three guidelines (9%) had dedicated sections for sleep (Table 4). Of the guidelines published in English, the term ‘sleep’ was most frequent in the guidelines from Australia and New Zealand (n = 16), Saudi Arabia (n = 11), Russia (n = 7) and the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (n = 6). The term ‘sleep’ was not mentioned in six guidelines.52,70–74

Discussion

CPGs have been developed to inform clinicians and healthcare professionals of best practice based on available evidence.17,18 For the management of COPD, a number of CPGs have been developed. The majority (n = 28, 80%) of CPGs included in this review, provided strategies to achieve sufficient physical activity; however, few (n = 2, 6%) provided specific recommendations that included a target type, context, intensity, duration and frequency of physical activity. No CPG provided specific recommendations for sedentary behaviour or sleep, and few suggested strategies to achieve improvements in these domains.

Specific recommendations and strategies concerning physical activity, sedentary or sleep behaviours were difficult to find within most CPGs. Only three (9%) guidelines had a dedicated section for physical activity or sleep, and no guideline had a dedicated section for sedentary behaviour.

The limited specific recommendations and strategies around movement behaviours, particularly around sedentary and sleep behaviours, may be a result of two factors: (1) lack of available evidence to support COPD-specific recommendations and strategies and (2) an assumption that improving physical activity will consequently improve sedentary and sleep behaviours.

Lack of available evidence to support COPD-specific recommendations

Since the early 2000s, there have been a number of studies reporting associations between the level of physical activity and important COPD-specific health outcomes, including risk of mortality and acute COPD exacerbation.12 Consequently, there has been an emergence of experimental studies exploring the effects of different intervention modalities on increasing physical activity levels in the COPD population;75 the available evidence supporting efficacious strategies to increase physical activity levels for people with COPD is however inconsistent and of average quality.12,75

In contrast, there are few studies that explore relationships between volumes, patterns and bouts of sedentary behaviour and COPD-specific health outcomes.11 A simple search for studies exploring the effects of interventions specifically targeting time spent in sedentary behaviour identified a single protocol.76 Similarly, while poor sleep quality is commonly reported by people with COPD15,77 and has demonstrated associations with adverse physiological and psychological health outcomes,14–16 few studies have explored therapeutic interventions to improve sleep in people with COPD without a coexisting sleep disorder.78–81

In the adult general population, more time spent in light intensity physical activity than sedentary behaviour,4–6 breaking up sedentary time more frequently,82 and sleep durations between 7 hours and 9 hours7 have demonstrated associations with favourable health outcomes; while prolonged periods of sedentary behaviour have demonstrated associations with deleterious health outcomes.83 Given that people with COPD spend a large proportion of the waking day in sedentary behaviour and have reduced night-time sleep durations,84 at a minimum these recommendations could be provided within CPGs for the management of COPD. Due to clinical and functional characteristics (lung hyperinflation, dyspnoea, fatigue, skeletal muscle dysfunction and acute exacerbations),12,85,86 changing time spent in sedentary and sleep behaviours may be more feasible in the COPD population, as opposed to changing time spent physically active.10,87

An assumption that improving physical activity will consequently improve sedentary and sleep behaviours

The emergence of research focused on physical activity in the COPD population, may be due to assumptions that improving physical activity will in turn improve sedentary and sleep behaviours. However, evidence for effects of physical activity interventions on time spent in sedentary behaviour in the general population does not support this assumption.88,89 Recent meta-analyses of interventions to reduce sedentary behaviour in the general population demonstrate that while interventions targeting sedentary behaviour produced clinically significant reductions in total sedentary time, interventions targeting physical activity produced little or no effect in reducing total sedentary time.88,89 For those people who increase time spent in moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity (≥3METs) to meet public health recommendations (≥150 min/week8), this time would still only comprise 2–3% of the 24-hour day. Some confusion has arisen around the term ‘inactivity’, which refers to being insufficiently active (i.e. failing to meet physical activity guidelines). ‘Inactive’ does not refer to levels of sedentary behaviour; one can be active (i.e. meet the physical activity guidelines) but still have undesirably high levels of sedentary behaviour.

Strengths and limitations

One strength of this review is the comprehensive search strategy used. In addition to electronic databases, clinical guideline databases, reference lists of systematic reviews and websites of authoritative bodies within the field were searched.

This review was strengthened by not setting limitations for publication language. The inclusion of non-English CPGs (n = 15, 43%) ensured that differences around specific recommendations and strategies for movement behaviours across countries were captured.

Conclusion

There were a number of CPGs for the management of COPD to provide specific recommendations and strategies around physical activity; however, no guideline provided specific recommendations for sedentary behaviour or sleep, and few provided strategies to achieve improvements in either of these domains. COPD-specific clinical characteristics and comorbidities likely pose additional barriers to achieving general population recommendations for physical activity for people with COPD. However, so far, there is no reason to assume that patterns and bouts of sedentary and sleep behaviours recommended for the general population differ to what would be required in the COPD population to improve health. People with COPD spend a large proportion of the day in sedentary behaviours and have reduced night-time sleep durations. Therefore, at a minimum, specific recommendations focused on changing time spent in sedentary and sleep behaviours could be provided within CPG for the management of COPD to achieve significant health benefits. To facilitate integration into clinical practice, recommendations and strategies around movement behaviours should be explicitly stated within CPGs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following people for assisting with the translation of clinical practice guidelines included in this review: Professor Esther May (Division of Health Sciences, University of South Australia), Dr Hanna Tervonen (School of Health Sciences, Division of Health Sciences, University of South Australia), Dr Dorota Zarnowiecki (School of Health Sciences, Division of Health Sciences, University of South Australia), Diana Knudsen (School of Pharmacy and Medical Sciences, Division of Health Sciences, University of South Australia), Bjorn Dueholm (School of Pharmacy and Medical Sciences, Division of Health Sciences, University of South Australia). We would also like to thank academic librarian Sarah McQuillen (Academic Library Services, University Library, University of South Australia) for providing advice on the search strategy and Professor Peter Frith (School of Health Sciences, Division of Health Sciences, University of South Australia) for providing his expertise on the final list of clinical practice guidelines to be included in this review.

Supplemental material: Supplementary material is available for this article online.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: HL and TWE have nothing to disclose. MTW reports grants from National Health and Medical Research Council and travel and honorarium from Boehringer Ingelheim and the Australian Physiotherapy Association, outside the submitted work. TO reports grants from Pennington Biomedical Research Center, National Health and Medical Research Council, and Australian Research Council, outside the submitted work.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, et al. Compendium of physical activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011; 43: 1575–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sedentary Behaviour Research Network. Letter to the editor: standardized use of the terms ‘sedentary’ and ‘sedentary behaviours’. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2012; 37: 540–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep 1985; 100: 126–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Buman MP, Winkler EA, Kurka JM, et al. Reallocating time to sleep, sedentary behaviors, or active behaviors: associations with cardiovascular disease risk biomarkers, NHANES 2005–2006. Am J Epidemiol 2014; 179: 323–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chastin SF, Palarea-Albaladejo J, Dontje ML, et al. Combined effects of time spent in physical activity, sedentary behaviors and sleep on obesity and cardio-metabolic health markers: a novel compositional data analysis approach. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0139984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Loprinzi PD, Lee H, Cardinal BJ. Daily movement patterns and biological markers among adults in the United States. Prev Med 2014; 60: 128–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Watson NF, Badr MS, Belenky G, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: a joint consensus statement of the American academy of sleep medicine and sleep research society. Sleep 2014; 38: 843–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organisation. Global recommendations on physical activity for health, http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241599979 (2010, accessed 11 May 2016).

- 9. Buckley JP, Hedge A, Yates T, et al. The sedentary office: a growing case for change towards better health and productivity. Expert statement commissioned by public health England and the active working community interest company. Br J Sports Med 2015: 0: 1–6. DOI: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cavalheri V, Straker L, Gucciardi DF, et al. Changing physical activity and sedentary behaviour in people with COPD. Respirology 2015; 21: 419–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Park SK, Larson JL. The relationship between physical activity and metabolic syndrome in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2014; 29: 499–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gimeno-Santos E, Frei A, Steurer-Stey C, et al. Determinants and outcomes of physical activity in patients with COPD: a systematic review. Thorax 2014; 69: 731–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Reid KJ, Baron KG, Lu B, et al. Aerobic exercise improves self-reported sleep and quality of life in older adults with insomnia. Sleep Med 2010; 11: 934–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Omachi TA, Blanc PD, Claman DM, et al. Disturbed sleep among COPD patients is longitudinally associated with mortality and adverse COPD outcomes. Sleep Med 2012; 13: 476–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Geiger-Brown J, Lindberg S, Krachman S, et al. Self-reported sleep quality and acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2015; 10: 389–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nunes DM, Mota RM, de Pontes Neto OL, et al. Impaired sleep reduces quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lung 2009; 187: 159–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Feder G, Eccles M, Grol R, et al. Using clinical guidelines. BMJ 1999; 318: 728–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schünemann HJ, Woodhead M, Anzueto A, et al. A guide to guidelines for professional societies and other developers of recommendations: Introduction to integrating and coordinating efforts in COPD guideline development. An official ATS/ERS workshop report. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2012; 9: 215–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015; 4: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ministry of Health Ukraine. [Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease adapted clinical guidelines based on evidence], http://www.dec.gov.ua/mtd/_hozl.html (2014, accessed 29 April 2016).

- 21. American Medical Directors Association. COPD management in the long-term care setting, http://www.paltc.org/product-store/copd-management-cpg (2010, accessed 16 December 2015).

- 22. Japanese Respiratory Society. [COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) guidelines fourth edition for the treatment and diagnosis], http://www.jrs.or.jp/modules/guidelines/index.php?content_id=61 (2014, accessed 29 April 2016).

- 23. Work Loss Data Insitute. COPD -- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In: Pulmonary (acute & chronic), http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=47575 (2013, accessed 16 December 2015).

- 24. From the Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), http://www.goldcopd.org/ (2015, accessed 27 April 2016).

- 25. Yang PI, Dabscheck DE, George DJ, et al. The COPD-X plan Australian and New Zealand guidelines for the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 2015, http://copdx.org.au/copd-x-plan/ (2015, accessed 27 April 2016).

- 26. NHG Working Group on Asthma and COPD in adults. [NHG standard COPD (Third revision)]. Huisarts Wet 2015; 58(4): 198–211. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Montes de Oca M, Varela MVL, Acuña A, et al. [Latinoamericana COPD guide - 2014 Based on evidence]. Off Publ Latin Am Assoc Thorax (ALAT) 2015: 3–43. [Google Scholar]

- 28. The National Board of Health and Welfare Sweden (Socialstyrelsen). [National guidelines for the treatment of asthma and COPD Support for governance and management], http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2015/2015-11-3 (2015, accessed 13 April 2016).

- 29. Bettoncelli G, Blasi F, Brusasco V, et al. The clinical and integrated management of COPD. An official document of AIMAR (Interdisciplinary Association for Research in Lung Disease), AIPO (Italian Association of Hospital Pulmonologists), IMER (Italian Society of Respiratory Medicine), SIMG (Italian Society of General Medicine). Multidiscip Respir Med 2014; 9: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Miravitlles M, Soler-Cataluña JJ, Calle M, et al. Spanish guideline for COPD (GesEPOC). Update 2014 Arch Bronconeumol 2014; 50: 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Task Force of GesEPOC. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) – Spanish guideline for COPD (GesEPOC). Arch Bronconeumol 2012; 48(supl 1): 2–58.23116901 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defence. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, http://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/cd/copd/ (2014, accessed 27 April 2016).

- 33. Russi E, Karrer W, Brutsche M, et al. Diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the Swiss guidelines. Respiration 2013; 85: 160–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Koblizek V, Chlumsky J, Zindr V, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Official diagnosis and treatment guidelines of the Czech Pneumological and Phthisiological Society; a novel phenotypic approach to COPD with patient-oriented care. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 2013; 157: 189–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ministry of Health Chile. [Clinical guide chronic obstructive pulmonary disease COPD], http://www.supersalud.gob.cl/difusion/572/articles-655_recurso_1.pdf (2013, accessed 27 April 2016).

- 36. Gupta D, Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Joint ICS/NCCP (I) recommendations. Lung India 2013; 30: 228–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Health Dictorate Norway. [National professional guidelines and guidelines for prevention, diagnosis and care], https://helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/nasjonal-faglig-retningslinje-og-veileder-for-forebygging-diagnostisering-og-oppfolging-av-personer-med-kols (2012, accessed 27 April 2016).

- 38. Figueroa Casas JC, Schiavi E, Mazzei JA, et al. [Recommendations for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of COPD in Argentina]. Medicina 2012; 72: 1–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. The Algerian Society of Pneumopathophysiology. [The chronic obstructive pulmonary diease practical guide for the practitioner], http://www.sapp-algeria.org/PDF/guide_bpco_2011.pdf (2012, accessed 27 April 2016).

- 40. French Language Pneumology Society. [Recommendation for clinical practice management of COPD]. Rev Mal Respir 2010; 27: 522–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement CBO. [Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of COPD update March 2010], http://www.nvalt.nl/uploads/Mn/U9/MnU99pqRBYK7a_zStHhumA/Richtlijn-Diagnostiek-en-behandeling-van-COPD-maart-2010.pdf (2010, accessed 27 April 2016).

- 42. Ministry of Health Malaysia, Academy of Medicine Malaysia, Malaysian Thoracic Society. Management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, http://www.moh.gov.my/attachments/4749.pdf (2009, accessed 29 April 2016).

- 43. Danish Health Authority. [COPD - Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Recommendations for early detection, monitoring, treatment and rehabilitation], http://www.sst.dk/˜/media/F6A8B61402814D59836C0CE6C710E732.ashx (2007, accessed 29 April 2016).

- 44. Huizar-Hernández V, Rodríguez-Parga D, Sánchez-Mécatl MÁ, et al. [Clinical practice guideline diagnosis and treatment of chronic obstructive lung disease]. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc 2011; 49: 89–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bellamy D, Bouchard J, Henrichsen S, et al. International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) guidelines: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Prim Care Respir J 2006; 15: 48–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Figueroa Casas JC, Schiavi E, Mazzei JA, et al. [Recommendations for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of COPD in Argentina]. Medicina 2012; 72: 1–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement CBO. [Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of COPD update March 2010], http://www.nvalt.nl/uploads/Mn/U9/MnU99pqRBYK7a_zStHhumA/Richtlijn-Diagnostiek-en-behandeling-van-COPD-maart-2010.pdf (2010, accessed 27 April 2016).

- 48. French Language Pneumology Society. [Recommendation for clinical practice management of COPD]. Rev Mal Respir 2010; 27: 522–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Russi E, Karrer W, Brutsche M, et al. Diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the Swiss guidelines. Respiration 2013; 85: 160–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gupta D, Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: joint ICS/NCCP (I) recommendations. Lung India 2013; 30: 228–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ministry of Health Malaysia, Academy of Medicine Malaysia, Malaysian Thoracic Society. Management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, http://www.moh.gov.my/attachments/4749.pdf (2009, accessed 29 April 2016).

- 52. Bellamy D, Bouchard J, Henrichsen S, et al. International primary care respiratory group (IPCRG) guidelines: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Prim Care Respir J 2006; 15: 48–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Miravitlles M, Soler-Cataluña JJ, Calle M, et al. Spanish guideline for COPD (GesEPOC). Update 2014. Arch Bronconeumol 2014; 50: 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Danish Health Authority. [COPD - Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Recommendations for early detection, monitoring, treatment and rehabilitation], http://www.sst.dk/˜/media/F6A8B61402814D59836C0CE6C710E732.ashx (2007, accessed 29 April 2016).

- 55. Chuchalin AG, Avdeev SN, Aysanov ZR, et al. Russian Respiratory Society Federal guidelines on diagnosis and treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, http://journal.pulmonology.ru/pulm/article/download/385/384 (2014, accessed 13 April 2016).

- 56. Kankaanranta H, Harju T, Kilpelainen M, et al. Diagnosis and pharmacotherapy of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the finnish guidelines. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2015; 116: 291–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sliwinski P, Gorecka D, Jassem E, et al. [Polish Respiratory Society guidelines for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease]. Pneumonol Alergol Pol 2014; 82: 227–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. High Authority of Health. [Care initiative guide: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease], http://www.has-sante.fr/portail/upload/docs/application/pdf/2012-04/guide_parcours_de_soins_bpco_finale.pdf (2014, accessed April 27 2016).

- 59. Khan JH, Lababidi HM, Al-Moamary MS, et al. The Saudi guidelines for the diagnosis and management of COPD. Ann Thorac Med 2014; 9: 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Anderson B, Conner K, Dunn C, et al. Diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), https://www.icsi.org/guidelines__more/catalog_guidelines_and_more/catalog_guidelines/catalog_respiratory_guidelines/copd/ (2013, accessed 27 April 2016).

- 61. University of Michigan Health System. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, http://www.med.umich.edu/1info/FHP/practiceguides/copd/copd.pdf (2012, accessed 27 April 2016). [PubMed]

- 62. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med 2011; 155: 179–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Guidelines and Protocols Advisory Committee. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), http://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/practitioner-pro/bc-guidelines/copd.pdf (1 January 2011, accessed 27 April 2016).

- 64. Abdool-Gaffar M, Ambaram A, Ainslie G, et al. Guideline for the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 2011 update. S Afr Med J 2011; 101: 63–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care (update guideline), https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/conditions-and-diseases/respiratory-conditions/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease (2010, accessed 13 April 2016).

- 66. Vogelmeier C, Buhl R, Criee CP, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and therapy of COPD issued by Deutsche Atemwegsliga and Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Pneumologie und Beatmungsmedizin. Pneumologie 2007; 61: e1–e40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bellamy D, Bouchard J, Henrichsen S, et al. International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) Guidelines: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Prim Care Respir J 2006; 15: 48–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Doherty DE, Belfer MH, Brunton S, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: consensus recommendations for early diagnosis and treatment. J Fam Pract 2006; 55: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 69. The National Board of Health and Welfare Sweden (Socialstyrelsen). [National guidelines for the treatment of asthma and COPD Support for governance and management], http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2015/2015-11-3 (2015, accessed 13 April 2016).

- 70. Bettoncelli G, Blasi F, Brusasco V, et al. The clinical and integrated management of COPD. An official document of AIMAR (Interdisciplinary Association for Research in Lung Disease), AIPO (Italian Association of Hospital Pulmonologists), IMER (Italian Society of Respiratory Medicine), SIMG (Italian Society of General Medicine). Multidiscip Respir Med 2014; 9: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Task Force of GesEPOC. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) – Spanish guideline for COPD (GesEPOC). Arch Bronconeumol 2012; 48(Suppl 1): 2–58.23116901 [Google Scholar]

- 72. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Weinberger SE, et al. Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Ann Intern Med 2011; 155: 179–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. University of Michigan Health System. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, http://www.med.umich.edu/1info/FHP/practiceguides/copd/copd.pdf (2012, accessed 27 April 2016). [PubMed]

- 74. Doherty DE, Belfer MH, Brunton S, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Consensus recommendations for early diagnosis and treatment. J Fam Pract 2006; 55: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Mantoani LC, Rubio N, McKinstry B, et al. Interventions to modify physical activity in patients with COPD: a systematic review. Eur Respir J 2016; 48(1): 69–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Orme M, Weedon A, Esliger D, et al. Study protocol for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease-Sitting and ExacerbAtions Trial (COPDSEAT): a randomised controlled feasibility trial of a home-based self-monitoring sedentary behaviour intervention. BMJ Open 2016; 6(10): 1–10. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Foley D, Ancoli-Israel S, Britz P, et al. Sleep disturbances and chronic disease in older adults: Results of the 2003 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Survey. J Psychosom Res 2004; 56: 497–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. McDonnell LM, Hogg L, McDonnell L, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation and sleep quality: a before and after controlled study of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 2014; 24: 14028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Lan CC, Huang HC, Yang MC, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation improves subjective sleep quality in COPD. Respir Care 2014; 59: 1569–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Soler X, Diaz-Piedra C, Ries AL. Pulmonary rehabilitation improves sleep quality in chronic lung disease. COPD 2013; 10: 156–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kapella MC, Herdegen JJ, Perlis ML, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia comorbid with COPD is feasible with preliminary evidence of positive sleep and fatigue effects. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2011; 6: 625–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Healy GN, Dunstan DW, Salmon J, et al. Breaks in sedentary time. Diabetes Care 2008a; 31: 661–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Wilmot EG, Edwardson CL, Achana FA, et al. Sedentary time in adults and the association with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and death: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2012; 55: 2895–2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Hunt T, Madigan S, Williams MT, et al. Use of time in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2014; 9: 1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Tödt K, Skargren E, Jakobsson P, et al. Factors associated with low physical activity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cross-sectional study. Scand J Caring Sci 2015; 29: 697–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Watz H, Pitta F, Rochester CL, et al. An official European respiratory society statement on physical activity in COPD. Eur Respir J 2014; 44: 1521–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Hill K, Gardiner P, Cavalheri V, et al. Physical activity and sedentary behaviour: applying lessons to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Inter Med 2015; 45: 474–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Prince S, Saunders T, Gresty K, et al. A comparison of the effectiveness of physical activity and sedentary behaviour interventions in reducing sedentary time in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. Obes Rev 2014; 15: 905–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Martin A, Fitzsimons C, Jepson R, et al. Interventions with potential to reduce sedentary time in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. Epub ahead of print 23 April 2015. DOI: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.